Chapter 63 Facial Reanimation Techniques

The care of a patient with facial paralysis requires careful examination of the overall clinical picture, including the patient’s age, medical status, etiology of the facial paralysis, other cranial nerve defects, prior reanimation surgery, goals, and expectations. The procedures offered run the gamut from complex dynamic procedures employing microvascular techniques and tissue transfer to simpler static procedures, and frequently a combination of techniques is necessary to achieve the best results. Protection of the integrity of the cornea is paramount throughout the duration of the patient’s facial paralysis. Generally, the upper and lower face receive separate consideration regarding functional and cosmetic procedures for the eye, and recreation of symmetry and function for the mouth. The reader is directed to Chapter 61 for a comprehensive discussion of eye reanimation for these patients and to Chapter 62 for an in-depth discussion of hypoglossal facial anastomosis.

DYNAMIC PROCEDURES FOR FACIAL REANIMATION

Nerve Grafting Procedures

Patient Selection

The ideal reanimation procedure in any patient with disruption of the facial nerve is reconstitution of the nerve by primary repair or by grafting to re-establish continuity between the facial nerve nucleus and facial musculature. The procedure should be done in a clean field as soon as possible after the injury. Factors affecting results include the condition of the nerve, the time after onset of paralysis, the presence of tumor in the nerve, and the adherence to microsurgical techniques of nerve repair. Ideally, the procedure should be done in the first 30 days; if not, and the results of repair are disappointing after 1 year.1

Surgical Technique

After trimming the ends of the nerve to achieve a healthy nerve for anastomosis devoid of trauma, debris, or neoplasm, the surgeon must assess the need for a graft. A primary repair offers no advantage if the two nerves are under tension, and this can be assessed if the nerves stay in good approximation without sutures. The fewest number of sutures necessary to achieve stable coaptation of the nerve suffice. Intracranially, sutures may be limited technically to one or two 9-0 or 10-0 monofilament sutures; in the temporal bone, no suturing is required; and extracranially, two or three sutures are sufficient. Nerve repair is traditionally either by epineurial or by fascicular repair techniques, and studies have not supported superiority of one over the other. Likewise, reversing grafts and clipping nonessential branches have not provided advantages.1

The medial branchial cutaneous nerve is selected when the greater auricular is unavailable, is too short, or lacks the additional necessary branching pattern.2 This graft is a sensory nerve of the arm, provides a good size match for the facial nerve, has a potential length of 20 cm, and usually has at least four branches. In comparison, the sural nerve, found behind the lateral malleolus in relation to the lesser saphenous vein, offers 35 cm in length, and an adequate branching pattern, but is generally larger in diameter than the facial nerve. We have successfully harvested the sural nerve using the minimally invasive endoscopic technique being employed for saphenous vein harvest.

We have been able to achieve a fair to superb facial nerve outcome in our nerve graft patients 80% of the time. Patients with paralysis caused by malignant tumors, older patients, and patients who had delay in repair tended to have poorer outcomes.3 Wax and Kaylie4 had no difference in facial nerve outcome, however, in patients who had a positive margin in the reconstructed nerve. In their series of 19 patients, they had a grade III or IV result in 50% of the patients in each group.

Nerve Substitution Procedures

Patient Selection

Patients may have either a cross facial nerve graft or a hypoglossal nerve substitution if they are not candidates for a primary repair. Ideally, these procedures also should be performed in the first 30 days after injury. Results with a hypoglossal/facial jump graft are acceptable when performed 1 year after injury, and a full hypoglossal transfer can be performed 2 years after injury, although the synkinesis and tongue weakness must be considered and discussed extensively.5

Surgical Technique

The hypoglossal nerve is found in relation to the posterior aspect of the digastric muscle. Visualization of the nerve usually requires retraction of the digastric superiorly. The nerve always passes lateral to the carotid artery, and retrograde dissection from this point is sometimes helpful, especially in the presence of significant adipose tissue. Using the nerve just distal to the ansa cervicalis allows for better therapy to retrain the patient’s smile because only tongue motion fibers are redirected up to the facial nerve. A small Penrose drain can be passed behind the nerve at this location and tightened using a self-retaining retractor. This drain gently elevates the hypoglossal nerve into the field and avoids obscuring tissue fluid at the time of repair. This procedure is being discussed in greater detail in Chapter 62.

The cross-face anastomosis was originally described by Scaramella6 and modified over the years by many surgeons. It is most useful when powering a free muscle graft for recreating a smile. It has been of more limited usefulness when trying to reanimate the entire facial nerve from a branch or branches of the contralateral side, which is why my preference has been for the jump graft in most patients.

Temporalis Muscle Transposition

Patient Selection

Patients who may be candidates for temporalis muscle transposition include patients (1) who have absent or poor facial function, either with spontaneous recovery 2 years after the onset of paralysis or 2 years after nerve repair or nerve grafting; (2) who are not candidates for or refuse facial nerve repair or grafting or facial/hypoglossal nerve grafting; (3) who have neurofibromatosis, ipsilateral CN X paralysis, or another condition that is a contraindication to facial/hypoglossal nerve grafting; and (4) who have undeveloped facial nerves or facial musculature, such as may occur with Möbius syndrome.3,4 The procedure has also been recommended to give reasonable function and symmetry while awaiting the results of a nerve graft to occur, and to augment the results of facial nerve repair or grafting.7

Patient Evaluation

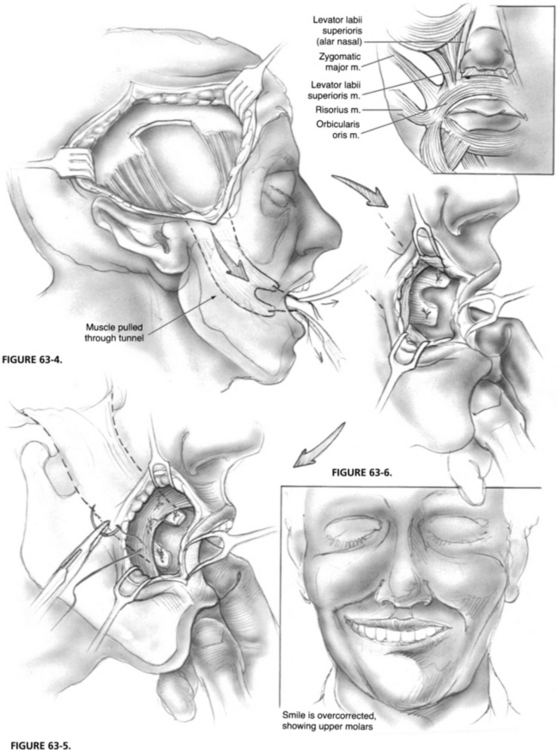

The patient’s smile on the unaffected side is classified, as described by Rubin,8 as (1) corner-of-the-mouth, or “Mona Lisa” (67% of the population); (2) canine, or “Jimmy Carter” (31% of the population); or (3) full-mouth, or “Lena Horne” (2% of the population).8 The appropriate smile can be partly recreated on the affected side by temporalis muscle transposition with careful consideration of how the various muscles of the mouth contract to form each type of smile.

Surgical Technique

Traditional temporalis muscle transposition is performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Small series have been reported with nontransposed temporalis muscle.9 The patient is positioned supine for surgery with the head in a doughnut head holder and turned so that the affected side is exposed. Hair is trimmed with scissors on either side of the part, and the entire surgical site is prepared. The scalp and lip/cheek incision sites are infiltrated with a solution of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine to improve hemostasis.

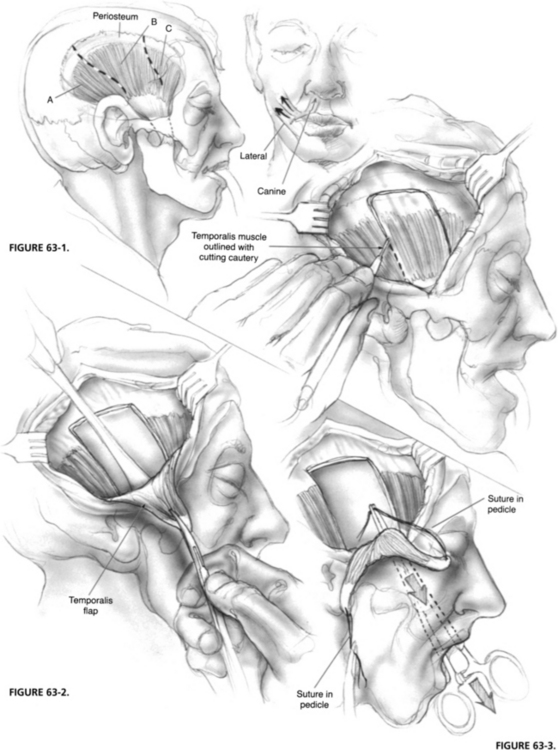

The initial incision is made in the scalp with a blade and continued through subcutaneous tissue and loose aponeurotic tissue with cutting, needle-tip cautery. After the temporalis muscle fascia has been identified, it is widely exposed from the zygomatic arch to just above the superior temporal line. A 4 cm wide segment (about two fingerbreadths) of the midportion of the muscle is outlined with the cautery (Fig. 63-1). A heavy periosteal elevator is used to elevate the muscle off the squamous portion of the temporal bone, beginning superiorly and moving inferiorly to the level of the zygomatic arch (Fig. 63-2). Care must be taken as the medial aspect of the muscle is elevated inferiorly to preserve its neurovascular supply from deep temporal nerves and vessels.

After the tunnel has been made, the temporalis muscle flap is bisected longitudinally, creating two 2 cm wide pedicles. A 2-0 polypropylene (Prolene) suture is placed through each pedicle in a figure-eight, and the needle is left on the suture (Fig. 63-3). Large clamps are used to pull the needles with sutures and attached muscle pedicles through the subcutaneous tunnel (Fig. 63-4). The pedicles of the temporalis muscle are sutured to facial muscle, if present, and submucosal layers so that one slip is above the oral commissure and one slip is below the commissure (Fig. 63-5). Additional sutures are used to secure the muscle so that the corner of the mouth is pulled toward the angle between the two pedicles to create a lateral smile that is overcorrected to show the first molar (Fig. 63-6). Overcorrection is crucial because a certain degree of settling occurs in the first few weeks. The resultant tissue defect above the zygoma can be ameliorated with commercially available or harvested tissue.

Results

The results of temporalis muscle transposition begin to be evident 3 to 6 weeks postoperatively, with the appearance of facial symmetry and resolution of the overcorrected smile. At 6 weeks postoperatively, patients are instructed to create a smile on the affected side by biting down. They learn to balance this voluntary smile with the smile on the unaffected side by practicing in front of a mirror. In some cases, these efforts can be enhanced by motor sensory re-education, a biofeedback technique in which a therapist uses electromyography to help the patient identify which muscles are being activated by voluntary effort.10 With time, the amount of conscious effort involved in creating a balanced smile decreases.

Complications

The main complications are hematoma and infection. There is a 20% incidence, however, of dehiscence of the connection of the muscle to the corner of the mouth, which can be successfully revised. Small series are available using a nontransposed temporalis muscle that avoids the defect in the temporal fossa and bulge of the transposed muscle over the zygoma. This technique has been described using either an intraoral9 or external11 lyexposure. A fascia graft is generally required to extend from the coronoid process to the mouth. The remainder of the procedure is the same.9,11

Free Muscle Flaps

Thompson12 first described the use of free (non-neurovascularized) autogenous muscle transplants to reanimate the paralyzed face; denervated muscle was placed in direct contact with muscle on the nonparalyzed side of the face. Subsequently, Frielinger13 introduced the use of free nonvascularized muscle grafts innervated by cross-face grafting. The techniques described by Thompson and Frielinger had limited success, but spurred interest in use of revascularized and innervated free muscle flaps.

Harii and associates14 reported using a free gracilis muscle graft to reanimate the chronically paralyzed face. The vascular supply to the graft was provided by microvascular anastomosis to the superficial temporal vessels. At first, innervation was supplied by anastomosis of the graft nerve to the deep temporal nerve, but later, cross-face grafting was performed instead to provide the possibility of symmetric, mimetic facial function.15

Numerous donor muscles have been proposed for free muscle graft rehabilitation of the paralyzed face, including the gracilis, rectus abdominis, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, and pectoralis minor.15 Ideally, the donor muscle has (1) a long neurovascular pedicle, (2) a cross-sectional area adequate to provide a flap of the width needed, (3) fiber length suitable to reproduce muscle action on the unaffected side, and (4) anatomy and physiology that permit harvesting with minimal morbidity at the donor site and small enough to avoid undesirable bulging in the face.16

Free muscle grafting has the disadvantage over muscle transposition of usually requiring several procedures, which also lengthens the time to final results. Harii and associates17 reported a one-stage procedure using the latissimus dorsi muscle and connecting the thoracodorsal nerve via the upper lip to contralateral facial nerve branches. In most centers, free muscle transfer has replaced regional muscle transposition for many facial nerve patients, particularly younger patients, patients who can tolerate a longer anesthetic, and patients with long survival expectations. The amount of movement with these techniques continues to disappoint in many cases, and extensive patient counseling is required.

STATIC PROCEDURE FOR FACIAL REHABILITATION

Lower Lip Rehabilitation

One method for rehabilitating the lower lip is to transpose the tendon of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle to the paralyzed orbicularis oris muscle.18 A tunnel is created between the tendon of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the lower lip depressor muscles. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle is left attached to the mandible, and the tendon is brought through the tunnel and attached to the lip depressor muscles. This procedure provides a symmetric smile in a patient with isolated lower lip paralysis because downward pull of the digastric muscle tendon counteracts upward pull of muscles elevating the lips.

In patients with oral incompetence, a procedure to reduce the size of the oral sphincter and transpose innervated muscle from the normal side to the denervated side can improve oral sphincter function. One such cheiloplasty procedure is V-wedge excision of a portion of the paralyzed lower lip; another is commissure Z-plasty.1

Surgical Management of Hyperkinesis

Some degree of synkinesis, hypokinesis, and hyperkinesis accompanies reinnervation of the face, whether nerve regeneration occurs with nerve grafting or nerve substitution techniques or with spontaneous recovery from a denervating injury. Synkinesis can be improved by sensorimotor re-education, in which the patient practices in front of a mirror, with the help of electromyography, to separate facial muscle activities.19,20 Hyperkinesis may be treated medically or surgically.21 Botulinum toxin injected into muscles involved in hyperkinesis causes temporary paralysis and temporary relief from hyperkinesis. When the effects of the botulinum toxin dissipate (3 to 6 months after injection), injection can be repeated. Surgically selective neurolysis or regional myectomy can provide longer lasting treatment for hyperkinesis. Selective neurolysis involves weakening or paralyzing innervation to the hyperkinetic muscle. The results of neurolysis are difficult to predict, however, and hyperkinesis may return, even after excision of a segment of nerve. For these reasons, regional myectomy is the currently preferred surgical technique for management of hyperkinesis in patients who fail or who are unwilling to use botulinum toxin.

1. May M., Schaitkin B., editors. May’s the Facial Nerve, 2nd ed, New York: Thieme, 2000.

2. Haller J.R., Shelton C. Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve: A new donor graft for repair of facial nerve defects at the skull base. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1048-1052.

3. Bascom D.A., Schaitkin B.M., May M., Klein S. Facial nerve repair: A retrospective review. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16:309-313.

4. Wax M.K., Kaylie D.M. Does a positive neural margin affect outcome in facial nerve grafting? Head Neck. 2007;29:546-549.

5. May M., Sobol S.M., Mester S.J. Hypoglossal-facial nerve interpositional jump graft for facial reanimation without tongue atrophy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;204:818-826.

6. Scaramella L.F. Cross-face nerve anastomosis: Historical notes. Ear Nose Throat J. 1996;75:347-352.

7. May M. Muscle transposition for facial reanimation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;110:184-189.

8. Rubin L. Reanimation of the Paralyzed Face. St Louis: Mosby; 1977.

9. Croxson G.R., Quinn M.J., Coulson S.E. Temporalis muscle transfer for facial paralysis: A further refinement. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16:351-356.

10. Sobol S.M., May M., Mester S. Early facial reanimation following radical parotid and temporal bone tumor resections. Am J Surg. 1990;160:382-386.

11. Byrne P.J., Kim M., Boahene K., et al. Temporalis tendon transfer as part of a comprehensive approach to facial reanimation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:234-241.

12. Thompson N. Autogenous free grafts and skeletal muscle. A preliminary experimental and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;48:11.

13. Frielinger G. A new technique to correct facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:44-48.

14. Harii K., Ohmori K., Torii S. Free gracilis muscle transplantation with microneurovascular anastomoses for the treatment of facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57:133-143.

15. O’Brien B.M., Pederson W.C., Khazanchi R.K., et al. Results of management of facial palsy with microvascular free-muscle transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:12-22.

16. Wells M.D., Manktelow R.T. Surgical management of facial palsy. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17:645-653.

17. Harii K., Asato H., Yoshimura K., et al. One-stage transfer of the latissimus dorsi muscle for reanimation of a paralyzed face: A new alternative. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:941-951.

18. Conley J., Baker D.C., Selfe T.W. Paralysis of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70:569-576.

19. Diels H.J. New concepts in nonsurgical facial nerve rehabilitation. In: Meyers E, (ed.) Advances in Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery. St Louis: Mosby—Year Book; 1995:289-315.

20. Diels H.J. Facial paralysis: Is there a role for a therapist? Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16:361-364.

21. May M., Croxson G.R., Klein S.R. Bell’s palsy: Management of sequelae using EMG rehabilitation, botulinum toxin, and surgery. Am J Otol. 1981;10:220-229.