Chapter 30 Facial Nerve Tumors

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Tumors of the facial nerve are rare causes of facial paralysis.1–5 The two most common tumors are facial nerve neuromas, which are intrinsic to the nerve, and facial nerve hemangiomas, which are extraneural in origin. This chapter focuses on these two types of facial nerve tumors. The techniques discussed can also be applied to other facial nerve neoplasms.

Because of their subtle presentation, facial nerve tumors may be difficult to diagnose and require a high degree of clinical suspicion.6,7 The presenting symptoms vary with the tumor location, size, and histology. Facial nerve neuromas that arise in the internal auditory canal (IAC) and cerebellopontine angle may manifest with a progressive sensorineural hearing loss similar to that caused by an acoustic tumor,8 and the true diagnosis may be established only at surgery.9,10 In a patient with a suspected acoustic tumor, the presence of coexisting facial nerve symptoms (rare with acoustic tumors) should warn the surgeon that a facial nerve tumor may be present.11,12

Facial nerve neuromas usually do not cause symptoms until they are fairly large and may manifest initially with hearing symptoms.12–14 Tumors arising in the middle ear may contact the ossicles and cause conductive hearing loss.15 In such cases, when a mass behind the tympanic membrane is invisible, the patient may be thought to have otosclerosis, and the correct diagnosis is made during tympanotomy for stapedectomy.6 When a middle ear mass is encountered in such a situation, a biopsy must not be done because a facial nerve paralysis is likely to develop postoperatively (see section on pitfalls of surgery).1,6,13,16,17

If the tumor erodes into the labyrinth (typically, the lateral semicircular canal at the external genu), the patient may present with dizziness.3 On examination, the fistula test result may be positive.

Facial nerve hemangiomas characteristically cause severe symptoms when very small.18,19 Similar to facial nerve neuromas, hemangiomas can occur in the IAC and manifest as acoustic tumors.20 They usually cause a sensorineural hearing loss that is severe for the size of the tumor. Extremely small hemangiomas of the geniculate ganglion can cause profound facial nerve symptoms.21–23 Hemangiomas are extraneural and cause paralysis by compression,24 but the small size of the tumor can make diagnosis by imaging studies very difficult. A high degree of clinical awareness is required.25

Patients with either tumor type may present with facial nerve symptoms. Typically, these patients have recurrent Bell’s palsy, although the facial nerve recovery is less complete with each episode.14 Facial nerve twitching can be present in some patients, and others may have facial paralysis with no recovery or a slowly progressive facial paralysis.26,27 When evaluating a patient with atypical facial nerve symptoms, one must always suspect facial nerve tumor.

Electric testing can help establish the diagnosis of a facial nerve tumor. Electroneuronographic results may be abnormal in patients with facial nerve tumors, even in the face of clinically normal function. Facial electromyography may show a pattern of simultaneous denervation and reinnervation in patients with tumors.18 This pattern is seen in slowly progressive, pathologic processes, and would not be expected with a rapid insult to the facial nerve, such as seen in Bell’s palsy.

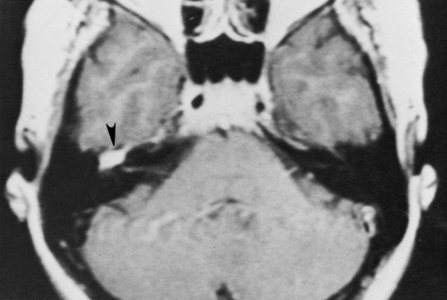

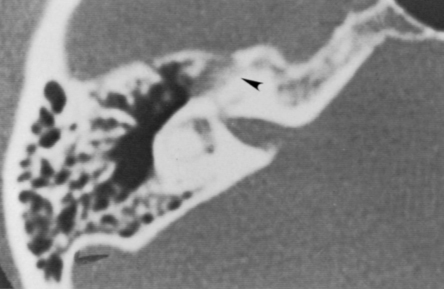

High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium may be sufficient to detect most facial nerve tumors (Fig. 30-1). Imaging of a facial nerve neuroma generally reveals a mass lesion and enlargement of the fallopian canal. Small facial hemangiomas at the geniculate ganglion may require high-resolution computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 30-2). These tumors exhibit characteristic bony changes, termed honeycomb bone.28 The medial extent of tumors arising at the geniculate ganglion can be assessed best with gadolinium-enhanced MRI.29 This medial extension has important ramifications regarding selection of surgical approach.

PATIENT SELECTION

The timing of surgery is perhaps the most difficult aspect of planning. Many patients with facial nerve tumors have normal or nearly normal facial function. The best anticipated facial function after a facial nerve graft is a House-Brackmann grade III to IV.16 Waiting too long to remove the tumor can adversely affect the ultimate facial nerve results, however. Patients with a long-standing facial nerve paralysis have worse results after facial nerve grafting than patients who have grafting when they have normal facial function.9,13 Extraneural tumors, such as facial nerve hemangiomas, can be removed with preservation of facial nerve continuity; early surgery in such cases may offer the best hope for excellent facial nerve function. Labyrinthine fistula can develop from bony erosion by the tumor and can lead to deafness and dizziness if the tumor is neglected too long.13,30

For an older patient in poor health who has a small tumor and good facial function, observation may be the best strategy. Younger patients with good facial function may also be followed, but they must be aware of the possible risk to the ultimate facial nerve outcome and to their hearing if surgery is delayed.12 In some cases, we follow patients until they show greater than 50% denervation by electroneuronography. When they reach this degree of denervation, we are concerned that facial nerve grafting after further loss of neural “firepower” would ultimately result in poor facial function.

Another option is planned surgical decompression to reduce pressure on nerve fascicles.31 This is an option for selected patients with small tumors for whom a facial palsy is an unacceptable outcome because it can give them several more years of normal facial function.32 When the tumor becomes neurosurgically significant, it is then resected. Decompression can be accomplished through the middle fossa or translabyrinthine approach, depending on the segments of the facial nerve that are involved.

Facial nerve neuromas in the IAC may be recognized during surgery for what was presumed to be an acoustic tumor.33 Tumor in the labyrinthine fallopian canal and the course of the facial nerve over the posterior aspect of an “acoustic tumor” are clues to the existence of a facial nerve neuroma. Preoperatively, we counsel patients with acoustic tumors about this unlikely possibility. When a facial neuroma is diagnosed intraoperatively, the options are to resect the tumor and place a nerve graft, and decompress the tumor. In some cases, the diagnosis of a facial nerve tumor is not made before the continuity of the facial nerve has been lost.

Radiation Therapy and Radiosurgery

Stereotactic radiotherapy and radiosurgery has been performed on several facial neuromas.34 Reports are anecdotal, and the outcome of this therapy for facial nerve tumors is completely unknown. Because this technique is investigational, treatment of facial tumors with radiosurgery should be performed only as part of an institutional review board–approved protocol. A case of malignant transformation after radiosurgery has been reported.35 This patient had partial excision of a facial nerve neuroma with postoperative radiation. Ten years later, the patient developed the cancer and had a poor outcome.

Patient Counseling

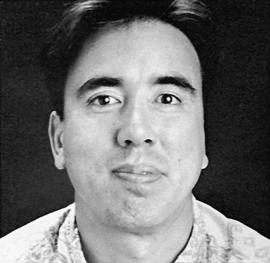

To describe a “good” result after facial nerve grafting, I tell my patients that they will look normal at rest and have active voluntary movement, but it will not be entirely symmetric motion. This asymmetry will be to the extent that family members will notice a difference, but a stranger on the street would not likely turn and stare (Fig. 30-3).

FIGURE 30-3 Patient postoperatively exhibiting House-Brackmann facial function grade IV 1 year after facial nerve graft.

Patients with a preoperative facial nerve palsy are told to expect worse postoperative facial function after nerve grafting. The longer the duration or the greater the severity of the preoperative palsy, the worse the ultimate result. The other potential risks and complications of surgery are also discussed according to the surgical approach needed. For middle fossa and translabyrinthine cases, the risks are similar to risks for patients with acoustic tumors treated through these approaches (see Chapters 48 and 49).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Preoperative preparation, patient positioning, and instrumentation are as described in Chapter 1. For patients needing a facial nerve graft, the upper neck is also prepared for harvesting of the greater auricular nerve.

Middle Fossa Approach

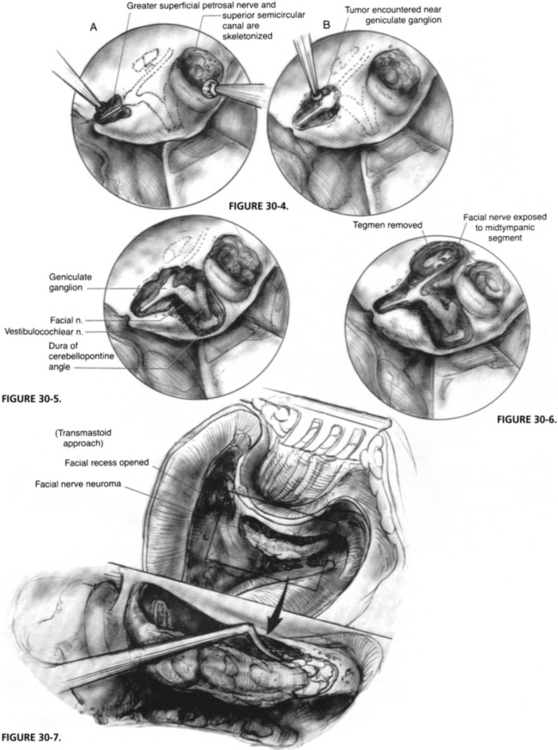

The initial middle fossa approach is carried out as described for acoustic tumors in Chapter 48. After the craniotomy window is made, the temporal lobe is supported by a retractor, and the greater superficial petrosal nerve and the skeletonized superior semicircular canal are identified. The greater superficial petrosal nerve is followed posteriorly to the geniculate ganglion (Fig. 30-4). For patients with tumor involvement in this area, extreme care must be taken during the dissection because a tumor can distort the anatomy.

The IAC is dissected, and the labyrinthine facial nerve is identified. The amount of IAC exposure varies with the degree of tumor extension in that area, and the need for access to place a graft (Fig. 30-5). The tegmen bone is also removed to expose the tympanic facial nerve (Fig. 30-6). Care is taken not to touch the ossicular heads with a burr during this removal because a sensorineural hearing loss would result.

Transmastoid Approach

If additional distal exposure is needed, a transmastoid approach to the facial nerve can also be performed, as described in Chapter 16. The facial recess is opened, and the nerve is exposed to the stylomastoid foramen. Around the facial nerve, it is best to thin the bone over it with a diamond burr, to use copious irrigation, and to remove the overlying “eggshell” of bone with an instrument such as a sickle or a whirlybird knife (Fig. 30-7). Because of tumor involvement or the need for additional room, the malleus head and incus can be removed and ossicular reconstruction performed at the end of the procedure.

Translabyrinthine Approach

The translabyrinthine approach is carried out as described in Chapter 49, and the facial nerve is skeletonized. The amount of medial bone removal varies with the tumor extent and the need for access for facial nerve grafting. The bone over the geniculate ganglion can be removed anteriorly to expose the greater superficial petrosal nerve (Fig. 30-8).

Tumor Removal

In some extraneural tumors (hemangiomas), a plane can be developed between the tumor and the nerve, allowing facial nerve preservation. In selected neuroma cases, some authors have reported tumor removal while maintaining partial continuity of the facial nerve.36

Graft Material

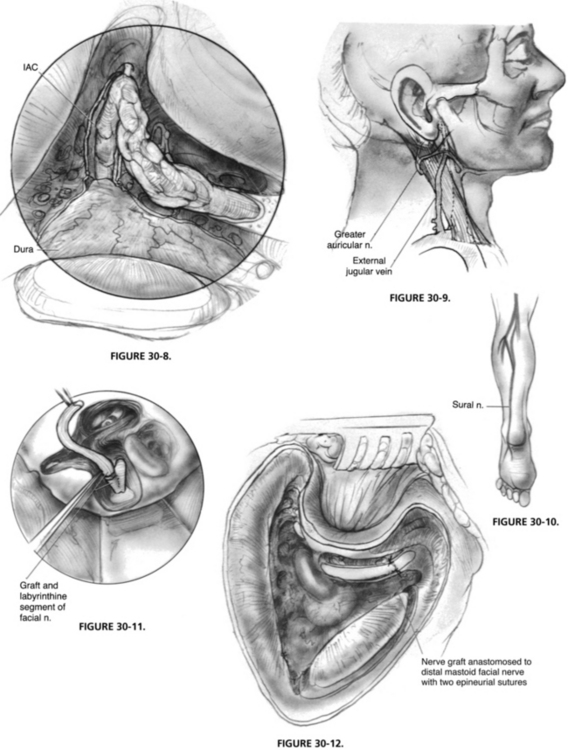

The greater auricular nerve can be found between the angle of the mandible and the tip of the mastoid process on the lateral surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle,37 posterosuperior to the external jugular vein (Fig. 30-9). The nerve can be harvested through an oblique skin incision placed in a skin crease. By dissecting the nerve from the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, ample length is obtained. Another option for a donor graft is the sural nerve (Fig. 30-10), which has a larger diameter and length than the greater auricular nerve.

Nerve Grafting

Within the temporal bone, if enough of the fallopian canal remains as a trough, placement of the graft in approximation to the nerve end is usually sufficient (Fig. 30-11). The anastomosis can be packed into place with microfibrillar collagen (Avitene), which forms a clot over the anastomosis.38 When sutures are needed, two or three epineurial sutures of 9-0 polypropylene (Prolene) on a cardiovascular needle work well (Fig. 30-12). The suture length is trimmed to 6 inches to make it easier to work under the microscope, and background material is cut, wetted, and placed beneath the anastomosis to give a smooth working surface. We prefer to cut the graft slightly longer than needed to ensure that no tension exists on the anastomosis. If possible, the graft is placed along the normal course of the facial nerve so that if further surgery is required, it can be easily identified. For patients requiring an ossicular reconstruction at a second stage, the graft of the horizontal facial nerve is placed in the epitympanum, superior to the oval window, so that it would not need to be manipulated during later ossicular reconstruction.

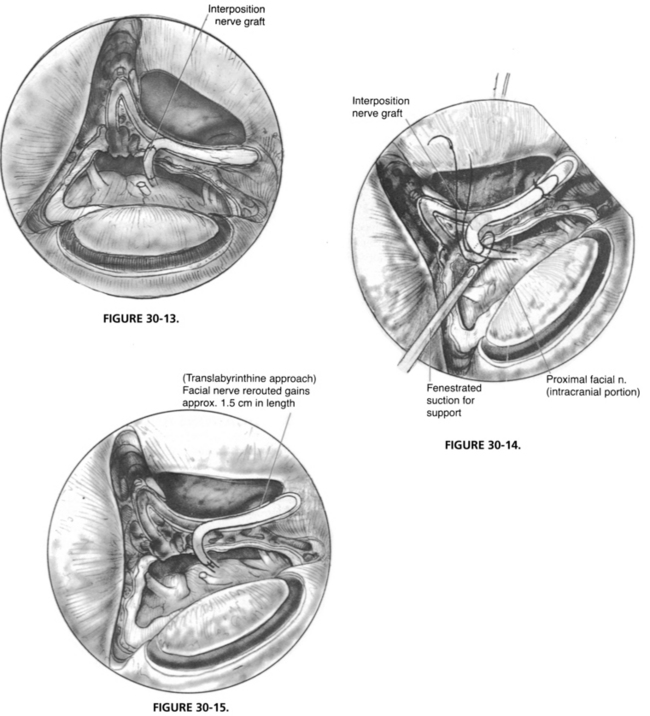

The placement of an anastomosis in the IAC or posterior fossa is much more difficult than an anastomosis performed within the temporal bone because the intracranial facial nerve has no epineurium (Fig. 30-13). Usually, a single through-and-through suture of 9-0 Prolene is sufficient.39 The suture is placed on the graft side first. When the suture is placed through the intracranial facial nerve stump, a fenestrated suction is used to support the facial nerve, and the needle is passed into a side hole of the suction (Fig. 30-14).40

Rerouting

Depending on the location and length of the facial nerve defect, it may be possible to remove the facial nerve from its canal and reroute it to gain extra length. This maneuver subjects the nerve to a great deal of manipulation and may interfere with its blood supply. For a defect in the cerebellopontine angle, rerouting (Fig. 30-15) gains additional nerve length, however, and allows primary anastomosis.

The wounds are closed as described in Chapter 29, and abdominal fat packing is used when indicated. The standard mastoid dressing is used. The postoperative care for tumor removal from the translabyrinthine and middle fossa approaches is similar to care given to patients with acoustic tumors removed through these approaches (see Chapters 48 and 49). An important aspect of postoperative care is attention to the paralyzed eye. This topic is discussed in detail in Chapter 61. Depending on the anticipated time and quality of facial function recovery, some patients require the placement of an upper eyelid spring or gold weight.

PITFALLS OF SURGERY

Facial nerve tumors, particularly neuromas, tend to involve the nerve over long distances of its course. Underestimation of tumor extent is an important problem and can be overcome by high-resolution imaging studies.28 High-resolution CT scanning of the temporal bone can show enlargement and erosion of the fallopian canal and indicate tumor involvement. When needed, gadolinium-enhanced MRI shows extension of the tumor into the IAC and posterior fossa.41

Some cases in our series were diagnosed elsewhere when a middle ear mass was encountered during tympanotomy to correct a conductive hearing loss. A biopsy must not be done on a middle ear mass in this situation. Of nine patients with tumors for which biopsies were done by the referring surgeons in our series, 88% experienced a postbiopsy facial paralysis.42 For a patient going to surgery for a stapedectomy, the development of a postoperative facial paralysis from the biopsy can be extremely disturbing. When a middle ear mass is encountered, the ear should be closed, and a radiologic, not histologic, evaluation should be done. A high-resolution CT scan showing enlargement of the fallopian canal yields a diagnosis of facial nerve tumor, and subsequent surgery can be planned based on the extent of the tumor.

RESULTS

Facial Nerve Neuromas

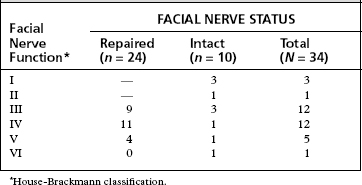

A review of a series of 64 facial nerve neuromas revealed that the facial nerve required repair (graft or primary anastomosis) in 72% of these patients.42 Of cases with 1 year or more of follow-up, 83% of the patients who had undergone repair had facial function graded as House-Brackmann grade IV or better (Table 30-1). For patients with preservation of facial nerve continuity, 70% had postoperative facial function of House-Brackmann grade III or better at 1 year (see Table 30-1). Only one patient in long-term follow-up experienced no recovery of postoperative facial function.

Facial Nerve Hemangiomas

Facial nerve hemangiomas tend to occur at the geniculate ganglion or in the IAC, with facial nerve repair most often required for tumors at the geniculate ganglion. In a report of 23 facial nerve hemangiomas, 47% required facial nerve repair.18 Most of the repaired nerves achieved a House-Brackmann grade III or IV by 1 year or more after surgery (Table 30-2). Hearing was maintained near the preoperative level in 64% of patients. One patient had postoperative anacusis from a cochlear fistula caused by the tumor.

TABLE 30-2 Postoperative Facial Nerve Results for 23 Facial Nerve Hemangioma Patients with >1 Year Follow-up

| Facial Nerve Grade∗ | FACIAL NERVE STATUS | |

|---|---|---|

| Repaired | Intact | |

| I | — | 7 |

| II | — | 2 |

| III | 2 | — |

| IV | 8 | 1 |

| V | 1 | — |

| VI | 2 | — |

∗ House-Brackmann classification.

From Shelton C, Brackmann DE, Lo WW, Carberry JN: Intratemporal facial nerve hemangiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 104:116-121, 1991.

COMPLICATIONS AND MANAGEMENT

Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks occurred in 6% of the neuroma series, and postoperative meningitis developed in 3%. Meningitis did not occur in patients who also experienced a cerebrospinal fluid leak. The management of these complications is similar to management after acoustic tumor removal by the translabyrinthine and middle fossa approaches (see Chapters 48 and 49).

1. Pulec J.L. Facial nerve neuroma. Laryngoscope. 1972;82:1160-1176.

2. Rosenblum B., Davis R., Camins M. Middle fossa facial schwannoma removed via the intracranial extradural approach: Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:739-741.

3. Pearman K., Welch A.R. Schwannoma of the intratemporal facial nerve: Case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1980;94:779-784.

4. Liliequist B. Neurinomas of the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve canal: A report of two cases. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1978;24:58-67.

5. Pulec J.L. Facial nerve tumors. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1969;78:962-983.

6. Jackson C.G., Glasscock M.E.III, Hughes G., Sismanis A. Facial paralysis of neoplastic origin: Diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:1581-1595.

7. Wiet R.J., Pyle G.M., Schramm D.R. Middle fossa and intratemporal facial nerve neuromas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:141-142.

8. Lee K.S., Britton B.H., Kelly D.L.Jr. Schwannoma of the facial nerve in the cerebellopontine angle presenting with hearing loss. Surg Neurol. 1989;32:231-234.

9. King T.T., Morrison A.W. Primary facial nerve tumors within the skull. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:1-8.

10. Dort J.C., Fisch U. Facial nerve schwannomas. Skull Base Surg. 1991;1:51-55.

11. Nelson R.A., House W.F. Facial nerve neuroma in the posterior fossa: Surgical considerations. In: Graham M.D., House W.F., editors. Disorders of the Facial Nerve. New York: Raven Press; 1982:403-406.

12. Bailey C.M., Graham M.D. Intratemporal facial nerve neuroma: A discussion of five cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97:65-72.

13. O’Donoghue G.M., Brackmann D.E., House J.W., Jackler R.K. Neuromas of the facial nerve. Am J Otol. 1989;10:49-54.

14. Pillsbury H.C., Price H.C., Gardiner L.J. Primary tumors of the facial nerve: Diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1045-1048.

15. Neely J.G., Alford B.R. Facial nerve neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1974;100:298-301.

16. Lipkin A.F., Coker N.J., Jenkins H.A., Alford B.R. Intracranial and intratemporal facial neuroma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:71-79.

17. Wiet R.S., Lohan A.N., Brackmann D.E. Neurilemmoma of the chorda tympani nerve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:119-121.

18. Shelton C., Brackmann D.E., Lo W.W., Carberry J.N. Intratemporal facial nerve hemangiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:116-121.

19. Mangham C.A., Carberry J.N., Brackmann D.E. Management of intratemporal vascular tumors. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:867-876.

20. Pappas D.G., Schneiderman T.S., Brackmann D.E., et al. Cavernous hemangiomas of the internal auditory canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:27-32.

21. Fisch U., Ruttner J. Pathology of intratemporal tumors involving the facial nerve. In: Fisch U., editor. Facial Nerve Surgery. Birmingham, AL: Aesculapius; 1977:448-456.

22. Balkany T., Fradis M., Jafek B.W., Rucker N.C. Hemangioma of the facial nerve: Role of the geniculate capillary plexus. Skull Base Surg. 1991;1:59-63.

23. Isaacson B., Telian S.A., McKeever P.E., Arts H.A. Hemangiomas of the geniculate ganglion. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:796-802.

24. Ylikoski J., Brackmann D.E., Savolainen S. Pressure neuropathy of the facial nerve: A case report with light and electron microscopic findings. J Laryngol Otol. 1984;98:909-914.

25. Glasscock M.E., Smith P.G., Schwaber M.K., Nissen A.J. Clinical aspects of osseous hemangiomas of the skull base. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:869-873.

26. Tew J.M.Jr., Yeh H.S., Miller G.W., Shahbabian S. Intratemporal schwannoma of the facial nerve. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:186-188.

27. Valvassori G.E. Neuromas of the facial nerve. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1978;24:68-70.

28. Lo W.W., Brackmann D.E., Shelton C. Facial nerve hemangioma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98:160-161.

29. Kertesz T.R., Shelton C., Wiggins R.H., et al. Intratemporal facial nerve neuroma: Anatomical location and radiological features. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1250-1256.

30. Sanna M., Zini C., Gamoletti R., Pasanisi E. Primary intratemporal tumours of the facial nerve: Diagnosis and treatment. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:765-771.

31. Angeli S., Brackmann D. Is surgical excision of facial nerve schwannomas always indicated? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:s144-s147.

32. Liu R., Fagan P. Facial nerve schwannoma: Surgical excision vs conservative management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:1025-1029.

33. Murata T., Hakuba A., Okumura T., Mori K. Intrapetrous neurinomas of the facial nerve: Report of three cases. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:507-512.

34. Litre C.F., Gourg G.P., Tamura M., et al. Gamma knife surgery for facial nerve schwannomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:853-859.

35. Shirazi M.A., Leonetti J.P., Marzo S.J., Anderson D.E. Surgical management of facial neuromas: Lessons learned. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:958-963.

36. Perez R., Chen J.M., Nedzelski J.M. Intratemporal facial nerve schwannoma: A management dilemma. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:121-126.

37. Pulec J.L. Facial nerve grafting. Laryngoscope. 1969;79:1562-1583.

38. House J.W. Facial nerve tumors and grafting. In: Brackmann D.E., editor. Neurological Surgery of the Ear and Skull Base. New York: Raven Press; 1982:77-80.

39. Barrs D.M., Brackmann D.E., Hitselberger W.E. Facial nerve anastomosis in the cerebellopontine angle: A review of 24 cases. Am J Otol. 1984;5:269-272.

40. Arriaga M.A., Brackmann D.E. Facial nerve repair techniques in cerebellopontine angle tumor surgery. Am J Otol. 1992;13:356-359.

41. Wiggins R.H., Harnsberger H.R., Salzman K.L., et al. The many faces of facial nerve schwannoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:694-699.

42. Alavi S., Shelton C. Facial nerve neuromas: Comparison of results of facial nerve preservation versus facial nerve repair. Trans Pacific Coast Otoophthalmol Soc. 74, 1993.