Chapter 9 Facelift with SMAS Flaps

Summary

Introduction

Facelift techniques

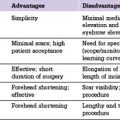

Some of the advantages and disadvantages of different facelift techniques are listed in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Advantages and disadvantages of different types of facelift techniques

| Facelift | Advantages | Disadvantages and complications |

|---|---|---|

| Skin only | Conceptual and technical simplicity | Secondary facelift deformities caused by skin tension |

| SMAS plication | No sub-SMAS dissection so technically less demanding and time consuming than procedures in which a flap is raised | Wide skin flap undermining; contour irregularities if sutures are not placed carefully; potential injury to facial nerve branches and parotid gland or duct; little if any midface improvement |

| SMASectomy | No sub SMAS dissection required; skin and SMAS can be shifted along different vectors so skin tension can be set low, and sideburn displacement and shifting of cervical wrinkles onto the face can be minimized | Wide skin undermining; facial nerve branches at risk when SMAS excised and sutured; may be contour irregularities; minimal improvement in midface |

| Deep plane | Single-layer dissection so flap elevation is easier and less time consuming than multilayer dissection and flap is thicker with a better blood supply | Potential excessive sideburn displacement, and shifting of cervical rhytids to the face; unnatural appearances caused by extraordinary tension; midface improvement not always as expected; facial nerve branches and other structures at risk |

| Composite | Similar to those for a deep plane lift, but also allows repositioning of orbicularis oculi and raising of lid-cheek junction | Similar to those of deep plane technique, but also may be prolonged periorbital edema and denervation of orbicularis oculi |

| Lamellar SMAS dissection and bidirectional | Skin and SMAS advanced bidirectionally in different amounts along separate vectors, and suspended under differential tension so avoiding skin tension, hairline displacement, and wrinkle shifts | Technique dependent and time consuming; flaps more fragile; facial nerve branches at risk |

| Extended SMAS | Improved effect in the mid face and infraorbital region and increased support of the lower eyelid | More technique dependent and time consuming; flap is more fragile; facial nerve branches at risk |

| High SMAS | Restoration of youthful upper cheek contour; filling of infraorbital region; increased support of lower eyelid; improved correction of nasolabial fold; readily combined with midface fat injections | Similar to those techniques using a sub-SMAS dissection |

| Subperiosteal | Dissection is familiar to most plastic surgeons and is largely deep to facial nerves; avoids many problems associated with skin-only procedures; improvement in infraorbital and upper midface areas in some cases | Generally longer recovery and often hard to obtain optimal improvement along jawline; problems of suspension sutures |

| Endoscopic | Minimal scarring | No means for skin excision; little improvement in lower cheek and along jawline |

| Midface | To improve midface area | Steep learning curve and fraught with complications, especially when performed through a blepharoplasty incision, including lid retraction, ectropion, canthal displacement and dry eye; disappointing results |

| Suture suspension | Seeming simplicity; easy marketability; can often be placed quickly under local or light anesthesia by inexperienced surgeons without surgical training; small incision; lower risk of hematoma, flap compromise and related complications | Support of the face cannot be predictably obtained; infection; extrusion; traction dimples; visible bowstringing; nerve injuries; facial dyskinesias; chronic pain syndromes; abnormal appearances during animation; a tight or choking feeling when used in the neck; palpable knots and sutures beneath the skin and occasional erosion of overlying skin |

| MACS (minimal access cranial suspension) | Seeming simplicity; no formal SMAS dissection; can be performed under local or light anesthesia; a shorter scar; shorter operating time. | Technique dependent and contour irregularities can result; problems associated with the placement of a stiff and rigid suture in the superficial layers of the face; injury to the parotid gland, parotid duct, facial nerves, and other deep facial structures |

| Short scar | Appeal to patients | Limited access to deep layer structures; redundant skin cannot be shifted along proper vectors; prevent skin from being properly excised |

| Mini-lift | Appeal to patients | Minimal improvement |

Skin only

Although the excision of skin formed the foundation of the facelift procedure for the first 70 years or so after its inception, this has ultimately been shown to be ineffective and conceptually flawed, and there are compelling reasons (Box 9.1) not to rely on skin resection only when surgically rejuvenating the face.

Box 9.1 Reasons why skin-only resection should not be relied on when surgically rejuvenating the face

Skin is intended to serve a covering function, not a structural or supporting one

SMAS

SMAS plication

Disadvantages of the SMAS plication technique are:

SMASectomy

Advantages of SMASectomy technique are:

Deep plane

A deep plane facelift consists of a sub-SMAS dissection first described by Skoog and later popularized by Lemon and Hamra in which the cheek skin and SMAS are raised together in one layer as a unified flap (Skoog flap). In the deep plane procedure the SMAS was used to reposition the lower cheek and jowl and the midface was then said to be elevated by ‘extraordinary tension’ on the preauricular portion of the flap.

Advantages of the deep plane technique include:

Composite

Advantages of the composite technique are:

Lamellar SMAS dissection and bidirectional facelift

Disadvantages of procedures that use lamellar SMAS dissections:

Extended SMAS

Disadvantages of the extended SMAS procedure compared with a standard dissection include:

High SMAS

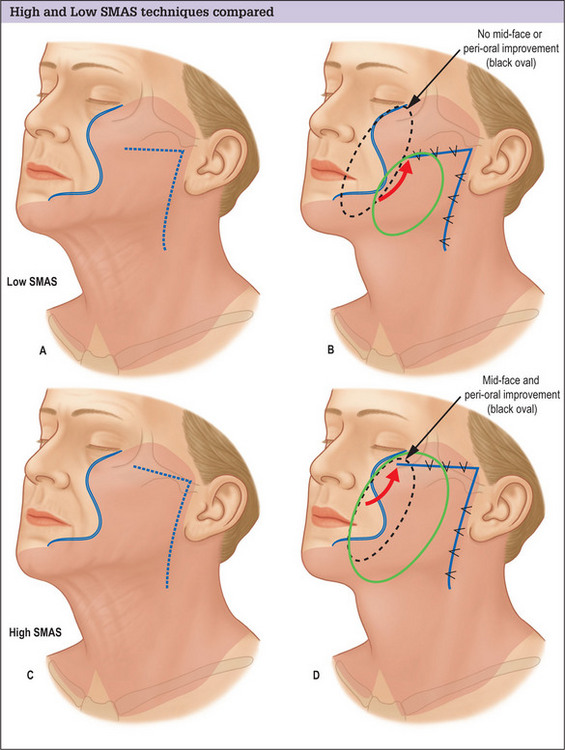

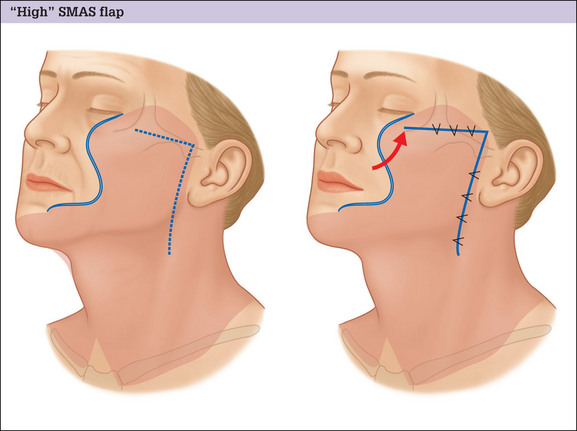

The conventional low cheek SMAS flap design in which the superior margin of the flap is planned below the zygomatic arch suffers the fundamental design flaw that it does not exert an effect on the tissues of the midface and infraorbital region. Low designs target the lower cheek and jowl only, and produce little if any improvement in the upper medial cheek area. Planning the flap higher, along the superior border of the zygomatic arch and making an extended dissection medially to mobilize midface tissue overcomes this problem and produces an improved result (Fig. 9.1A-D).

Advantages of a high SMAS plan include:

For many patients, the repositioning of midface tissue obtained with a high SMAS flap will be satisfactory in achieving the desired effect, and no additional or separate midface lift procedure will be required (Fig. 9.2A&B).

Subperiosteal

Potential advantages of a subperiosteal facelift include:

Potential disadvantages of the subperiosteal technique include the following:

Midface

Although there is merit in the idea of rejuvenating the midface, isolated midface lift procedures are still evolving, and have not been perfected. Most procedures have a steep learning curve and have been fraught with complications, especially when performed through a blepharoplasty incision. These complications include lid retraction, ectropion, canthal displacement and dry eye problems. As a result, many midface lift techniques have come to incorporate potentially problematic aggressive adjunctive surgical maneuvers including can thotomies, canthoplasties and orbicularis oculi muscle suspensions to prevent these problems. These maneuvers often result in a changed look that is disturbing to many patients, however, and carry a high risk of significant and troublesome complications of their own.

Suture suspension

Advantages of suture-lift procedures include:

Disadvantages of suture-lift procedures include:

MACS lift

The MACS procedure has evolved and has been refined from its original description in which one or two plication sutures were placed and non-absorbable permanent monofilament sutures were used. Multiple sutures are now generally placed to more specifically target the midface, cheek, jowl and lateral neck, and this is said to distribute improvement more uniformly over the face and produce a more natural and long-lived improvement. Softer, absorbable sutures have also been substituted for the stiffer more rigid non-absorbable sutures originally recommended.

Potential advantages of the MACS technique include:

Potential disadvantages of the MACS technique include:

Short-scar

Short-scar incision plans suffer the drawbacks that they:

Indications

Patients with significant facial atrophy and age-related facial wasting achieve suboptimal improvement from both surface treatments of facial skin and surgical lifts. Smoothing skin will not disguise a drawn, ill, or haggard appearance resulting from the loss of facial volume, and it is difficult to create natural and attractive contours by lifting and repositioning tissues that have abnormally thinned with age. These patients may require volume replacement, by autologous fat grafting or other means, in conjunction with their surgical procedure to achieve a satisfactory result.

Preoperative Planning

Temporal incision

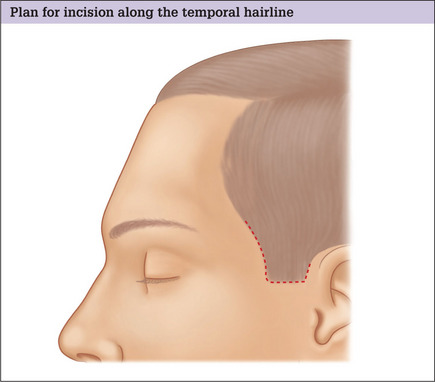

Patients best suited for this incision plan are usually young and troubled by mild cheek laxity only. In many other situations however, larger skin shifts and the presence of sparse temple hair can result in unnatural and tell-tale displacement of the temporal hairline and sideburn if such a plan is used (Fig. 9.3A&B).

Proper analysis, careful planning and the use of an incision along the hairline, when indicated, can avert this problem with out compromising the overall outcome of the procedure (Fig. 9.4A&B).

Important factors in choosing incision placement

Distance between the lateral orbit and anterior aspect of the temporal hairline

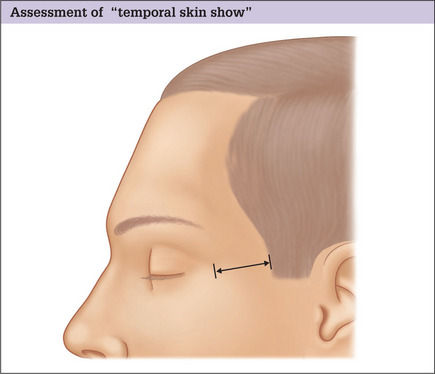

In choosing the location of the temporal portion of the facelift incision it is important to note the distance between the lateral orbit and the anterior aspect of the temporal hairline (Fig. 9.5) because this distance is aesthetically significant and generally increases with age.3 In healthy, youthful-appearing individuals it usually measures no more than 4–5 cm, but in older patients, or in those who have had a prior facelift, it will often be seen to be considerably more.

Estimate of the skin redundancy over the upper cheek

Equally important as the distance from the lateral orbit to the temporal hairline, is the surgeon’s estimate of the skin redundancy over the upper cheek, and therefore the skin shift that will occur when the facelift flap is repositioned.4 This can be easily assessed by simply pinching up redundant skin and measuring it. Assessment of skin redundancy over the cheek, in conjunction with the amount of existing temporal ‘skin show’, allows rational selection of the best site for temporal incision placement.

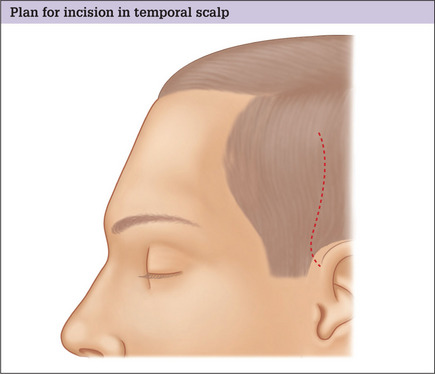

When to place the incision in the traditional location

In patients in whom minimal temporal skin shift will occur and for whom the temporal hairline will remain within 5 cm of the lateral orbit, the temporal portion of the facelift incision can be placed in the traditional location 4–5 cm within the temporal scalp, extending superiorly up from the superior aspect of the helical facial junction (Fig. 9.6).

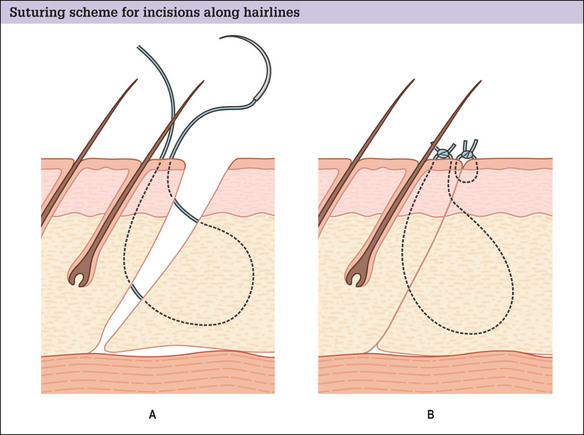

When to place the incision along the hairline

When the temporal hairline is predicted to be moved more than 5 cm away from the lateral orbit, however, or the sideburn hair shifted above the junction of the ear with the scalp, consideration should be given to placing the incision along the hairline (Fig. 9.7) rather than within the temporal scalp. This incision will allow large postero superior skin flap shifts while simultaneously providing maximum improvement in the upper lateral face.5 If it is made with care and closed under no tension, the resulting scar is usually inconspicuous and far less trou-blesome for the patient than a displaced hairline (see Fig. 9.3A&B)

Patient considerations

The patient should be informed that placing the incision in a traditional location within the temporal scalp will help conceal the scar, but often at the expense of a large and objectionable displacement of the temporal hairline and sideburn, and compromised improvement over the temporal face. This inevitably results in an old and unnatural appearance and is usually immediately obvious, even upon a casual glance and at a distance.

Preauricular incision

Traditional incision vs retrotragal incision

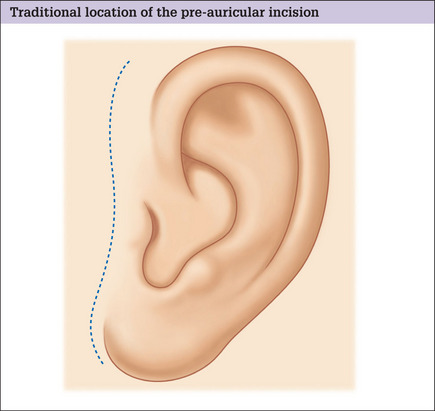

Traditionally, incisions in the preauricular region are made well anterior to the anterior border of the helix and continued inferiorly, anterior to the tragus (Fig. 9.8). This design, however, works well only for the unusual patient with cheek and tragal skin of similar characteristics who, in addition, exhibits favorable healing. Unfortunately, most patients have a marked gradient of color, texture, and surface irregularities over the preauricular area and a tell-tale mismatch will be evident, even in the presence of an inconspicuous scar.

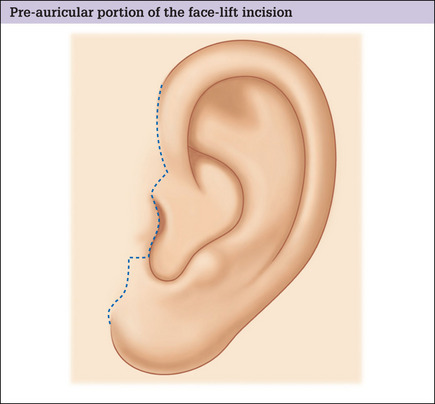

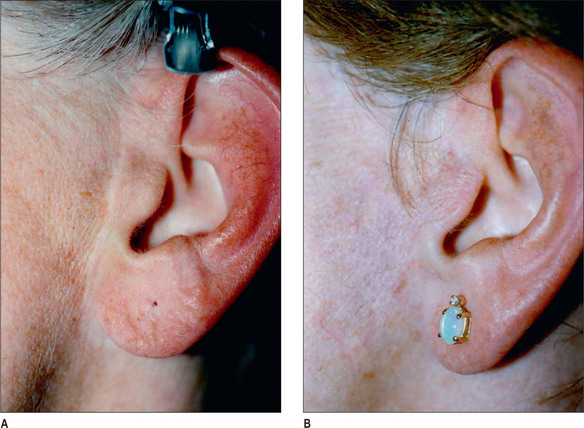

For these reasons, and in all but the unusual case, the preauricular portion of the facelift incision should be precisely placed along the posterior margin of the tragus, rather than in the pretragal sulcus (Fig. 9.9). In this location a mismatch of color, texture, or surface irregularities will not be noticed and the scar, if visible, will appear to be a tragal highlight6 (Fig. 9.10A&B).

In addition, and despite claims to they contrary, a properly planned and executed incision along the margin of the tragus will not produce tragal retraction or other anatomic irregularity (Fig. 9.11A&B).

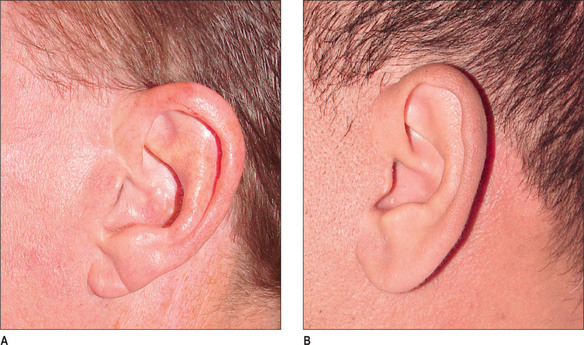

In the male patient, the tragus can be kept free of beard hair by intraoperative destruction of beard follicles from the underside of the tragal flap (Fig. 9.12A&B).

The superior portion of the preauricular incision should be planned as a soft curve in the helicofacial sulcus paralleling the curve of the anterior border of the helix. This will result in a natural-appearing width to the helix and the resultant scar, if visible, will appear to be a helical highlight.

At the inferior portion of the tragus the incision must turn anteriorly and then again inferiorly, into the crease between the anterior lobule and cheek. If a more relaxed plan is made, or if a straight line incision is used, skin settling and scar contraction will result in crowding of the incisura, obliteration of the inferior tragal border, and a tell-tale elongated and ‘chopped off’ tragal appearance (Fig. 9.13).

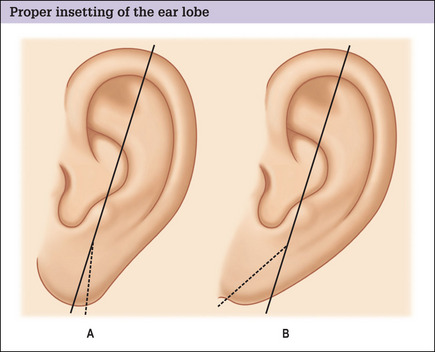

Perilobular incision

To obtain a natural perilobular appearance, it is essential to preserve the natural sulcus between the ear lobe and the cheek and to avoid excision of this aesthetically important anatomic subunit.7 This is accomplished by marking the incision a 1–2 mm inferior to this junction. All other factors being equal, a superior result will be obtained when such a plan is used, in comparison to any plan in which the incision is placed directly in the sulcus.

Postauricular incision

Traditionally, the postauricular portion of the facelift incision has been made over the posterior surface of the concha. This was done as part of a well-intended effort to offset inevitable descent of the postauricular flap and inferior migration of the resulting scar that occurred when skin was tightened in an attempt to improve neck contour. Many surgeons have since come to realize that such a plan embodies erroneous assumptions and can result in undesirable effects including hypertrophic scarring, postauricular webbing and obliteration of the auriculomastoid crease.8

Occipital incision

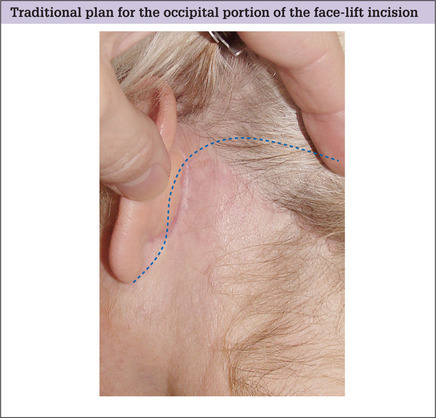

Planning the location for the occipital portion of the facelift incision is conceptually similar to that of the temple region and the incision plan must address similar concerns of hairline displacement and scar visibility. Traditionally this incision is arbitrarily placed transversely, high on the occipital scalp, in a well-intended but usually counter-productive attempt to hide the resultant scar (Fig. 9.14).

Important factors in determining incision placement

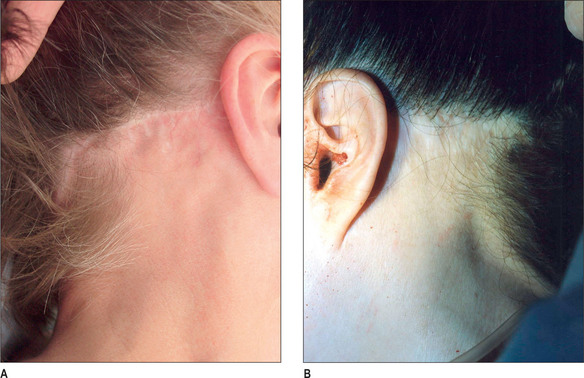

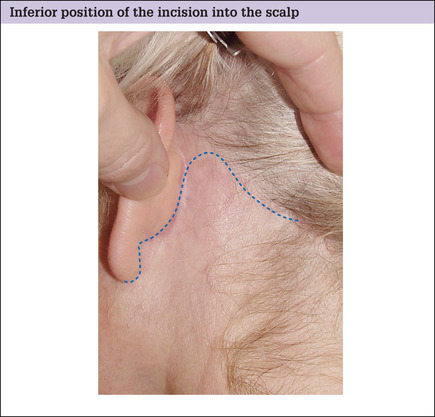

For patients with a small amount of neck skin redundancy is small and for whom excision of postauricular skin is unnecessary, such a plan is appropriate and will result in a well-concealed scar. Patients in this category are usually young and troubled by mild neck deformity only. In these situations the incision is used for access to the lateral neck only, and not as a means to remove postauricular skin. Skin excision using this incision plan will result in the advancement of neck skin into the occipital scalp and ‘notching’ of the occipital hairline (Fig. 9.15A&B).

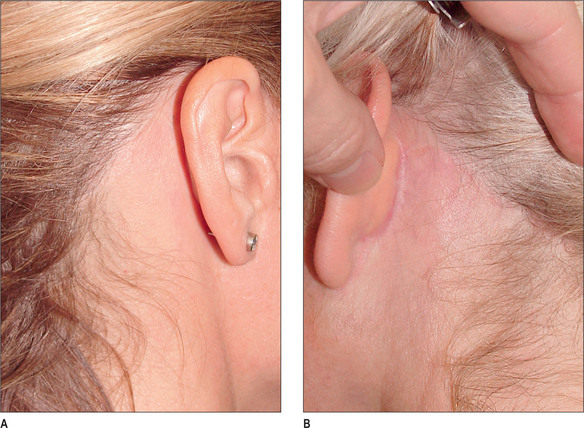

Although not all patients will recognize this deformity for what it is, most are nonetheless self conscious of it, especially those who wear their hair up or back or who lead active lives where wind, water and outdoor activities may displace camouflaging wisps of remaining hair. Proper analysis, careful planning and the use of an incision along the hairline when indicated, can avert this problem with out compromising the end result (Fig. 9.16A&B).

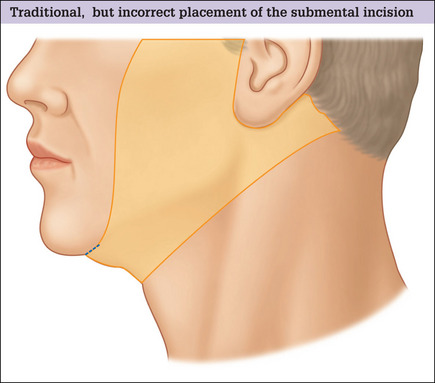

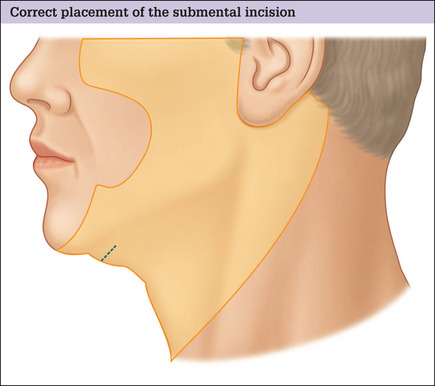

Submental incision

Most facelift patients require modification and repair of the neck and submental regions that can only be performed through a submental incision, and optimal improvement in the neck can generally not be obtained unless a submental access incision is made.9–11 Traditionally this incision is placed directly in and along the submental crease in a well intended, but counter-productive attempt to conceal the resulting scar(Fig.9.18). This incision plan should be avoided, however, because:

A more posterior placement of this incision will eliminate these problems, but still result in an inconspicuous and well-concealed scar (Fig. 9.19 and Fig. 9.20A-D).

The submental incision should be placed well posterior but parallel to the submental crease at a point lying roughly one half of the distance between the mentum and the hyoid (Fig. 9.21). This usually corresponds to a site situated approximately 1 cm posterior to the crease.

The incision should be approximately 3.5–4.5 cm in length, but may be made longer provided neither end will be advanced up upon a visible portion of the face when skin flaps are shifted. Healing will be best and the scar best concealed if it is made as a straight rather than a curved line (Fig. 9.22).

Operative Approach

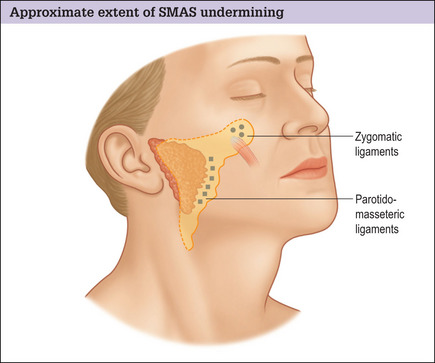

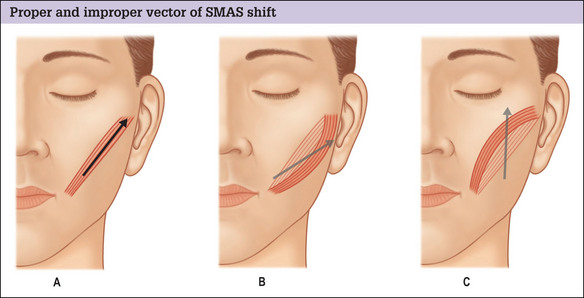

Planning modification of the SMAS

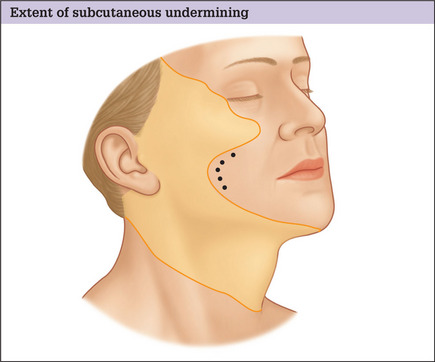

All patients undergoing a facelift will benefit from some modification of the SMAS and a high posterosuperior advancement of the cheek SMAS serves as the fundamental step in rejuvenation of the face and avoidance of secondary deformities (Fig. 9.23A&B).

Operative technique

Skin flap elevation

Temple incision and flap dissection

Flap dissection with traditional incision on the temporal scalp

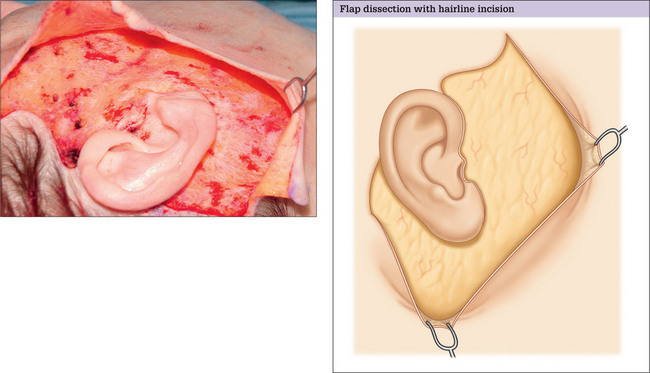

Flap dissection with incision along the temple hairline

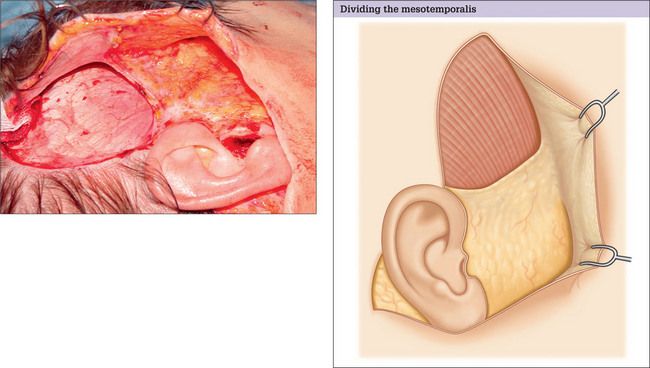

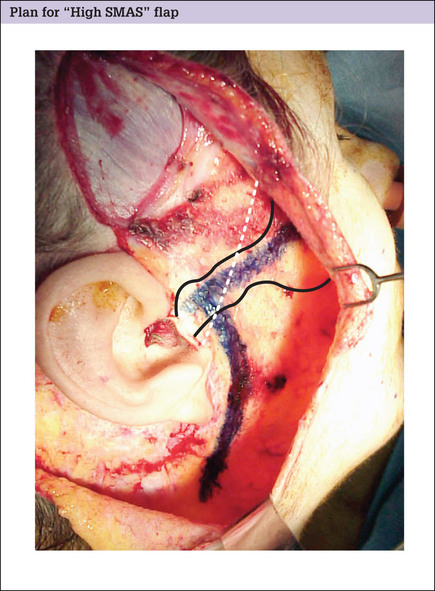

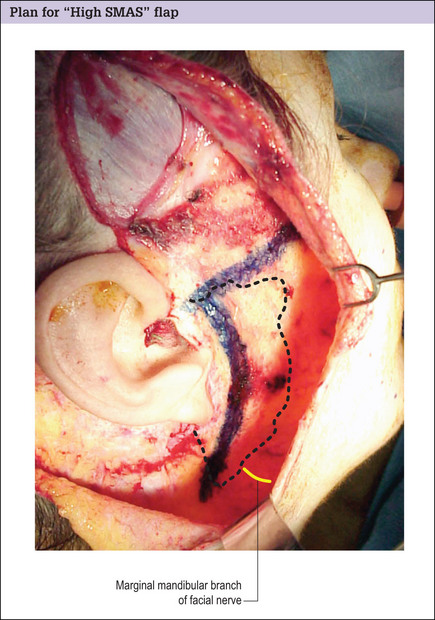

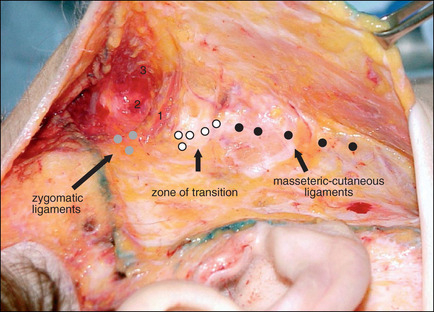

Plan for high SMAS flap

Advantages of the high flap

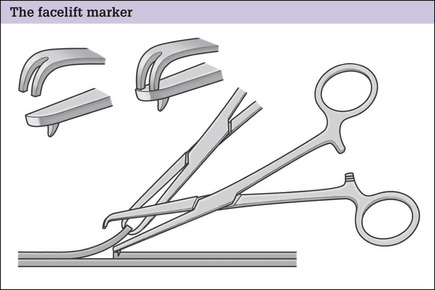

Incising the SMAS and flap elevation

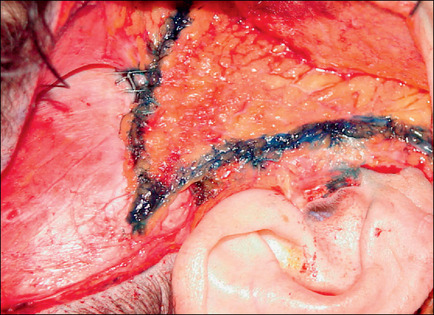

SMAS suspension

Securing the superior margin

Variation in the management of the superior margin of the SMAS flap

Securing the posterior margin of the SMAS flap

Regardless of how the superior margin of the flap is secured, some trimming of the posterior margin of the cheek SMAS flap is invariably required thereafter to allow an edge-to-edge approximation of the SMAS flap to the SMAS remnant in the preauricular region. Overlapping of the SMAS in the preauricular area is functionally unproductive and artistically inappropriate because such an arrangement lends no additional support to the anterior face and obliterates natural preauricular contours and the pretragal hollow.

Use of excess tissue as a postauricular transposition flap

Drain placement

Drains are used routinely and experience has shown that they reduce postoperative ecchymosis and seromas, and allow patients to return to their work and social lives sooner. Drains will not, however, substitute for poor hemostasis and will not prevent hematoma formation.

Skin flap repositioning and suspension suture placement

Points of skin flap suspension

Incision to exteriorize the lobule

Skin flap trimming and closure

Trimming and closure of the postauricular skin flap

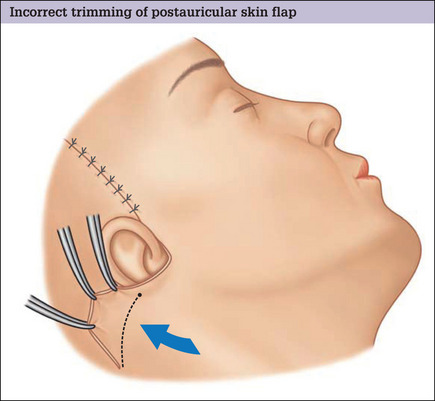

It is an error to excise any skin over (superior to) the apex of the occipitomastoid incision and to shorten the postauricular flap along the long axis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle as is commonly practiced. Despite an apparent redundancy in this area when the patient is supine on the operating table, there is never a true skin excess at this location. This deceptive pseudoexcess of skin is present only because of the patient’s high shoulder position in the supine position, and will vanish when the patient sits up and the shoulders drop to a normal location. Skin along the long axis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the postauricular region is also needed for side-to-side head tilt. Inappropriate excision of skin over the apex of the occipitomastoid defect is the underlying cause of hypertrophic healing in the postauricular region and a wide postauricular scar (Fig. 9.34).

Trimming and closure of the occipital incision

If there is a dog-ear

Trimming and closure in the preauricular area

Insetting the lobule

Closure of the temporal incision

Submental incision closure

Optimizing outcomes

Complications

Complications depend on the facelift technique used (see Table 9.1) and include:

Postoperative Care

Return to normal activities

Patients are asked to set aside 2–3 weeks to recover from surgery. Patients who are doing well and not experiencing problems are allowed to return to light office work and casual social activity 9–10 days after surgery. If a patient’s job entails more strenuous activity or physical labor, a longer period of convalescence may be required.

1. Marten T.J. Lamellar high SMAS face and midface lift. In: Foad N., editor. The art of aesthetic surgery. St Louis: QMP; 2005:1110-1193.

2. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. Mastery of plastic and reconstructive surgery. Boston: Little Brown, 1994;1873-1902.

3. Marten T.J. Facelift. Planning and technique. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24(2):269-308.

4. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. Deep layer techniques in cervico-facial rejuvenation. Deep facelifting. Thieme Medical. 1994;104(5):1521-1523.

5. Marten T.J. Customized incisions in facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Surg J. 1999;105(7):2620.

6. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. Facelift for the active man. In: Instructional courses in plastic surgery. St Louis: CV. Mosby; 1991:11-26.

7. Marten T.J. Secondary rejuvenation of the face. In: Mathes S., editor. Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2006:715-764.

8. Marten T.J. Periauricular face lift incisions and the auricular anchor. Plast Reconstr Surg. 105(7), 1999.

9. Marten T.J. Cervical contouring in facelift. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2003.

10. Marten T.J. Management of the full, obtuse neck. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2005;25(4):105-111.

11. Marten T.J., editor. Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 16. 2002:303-304. Facelift – state of the art

12. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. The submental crease and elimination of the double chin Deformity at rhytidectomy. Aesthetic Surgery. 10. 1990:10-11.

13 Marten TJ. Maintenance facelift: early facelift for younger patients. In: Marten TJ, ed. Facelift: state of the art. Seminars in Plastic Surgery 2002; 16(4):375–390.

14. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. Surgical correction of the crow’s feet deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20(2):295-302.

15. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. Orbicularis oculi myoplasty: surgical treatment of the crow’s feet deformity. Operative Techniques. In Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995.

16. Marten T.J. Open foreheadplasty. In: Knize D., editor. The forehead and temporal fossa: anatomy and technique. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

17. Marten T.J. Forehead aesthetics and pre-operative assessment of the foreheadplasty patient. In: Knize D., editor. The forehead and temporal fossa: anatomy and technique. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

18. Connell B.F., Marten T.J. The male foreheadplasty – recognizing and treating aging in the upper face. Clin Plast Surg. 1991;18(4):653-687.

19. Marten T.J. Hairline lowering during foreheadplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(1):224-236.