CHAPTER 29 Face and scalp

SKIN

The scalp and buccolabial tissues are described here. The structure of the eyelids is described in Chapter 39.

BUCCOLABIAL TISSUE

Lips

In the upper lip, a narrow band of smooth tissue related to the subnasal maxillae marks the point at which labial mucosa becomes continuous with gingival mucosa. The corresponding reflexion in the lower lip coincides approximately with the mentolabial sulcus, and here the lip is continuous with mental tissues. The upper and lower lips differ in cross-sectional profile in that neither is a simple fold of uniform thickness. The upper lip has a bulbous asymmetrical profile: the skin and red-lip have a slight external convexity, and the adjoining red-lip and mucosa a pronounced internal convexity, creating a mucosal ridge or shelf that can be wrapped around the incisal edges of the parted teeth. The lower lip is on a more posterior plane than the upper lip. In the position of neutral lip contact, the external surface of the lower lip is concave, and there is little or no elevation of the internal mucosal surface. The profile of the lips can be modified by muscular activity.

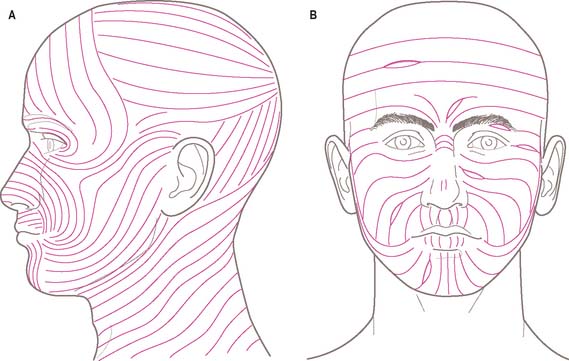

RELAXED SKIN TENSION LINES AND SKIN FLAPS ON THE FACE

The direction in which facial skin tension is greatest varies regionally. Skin tension lines which follow the furrows formed when the skin is relaxed are known as ‘relaxed skin tension lines’ (Borges & Alexander 1962). In the living face, these lines frequently (but not always) coincide with wrinkle lines (Fig. 29.1) and can therefore act as a guide in planning elective incisions.

SOFT TISSUE

FASCIAL LAYERS

Fascial layers and tissue planes in the face

Parotid fascia (capsule)

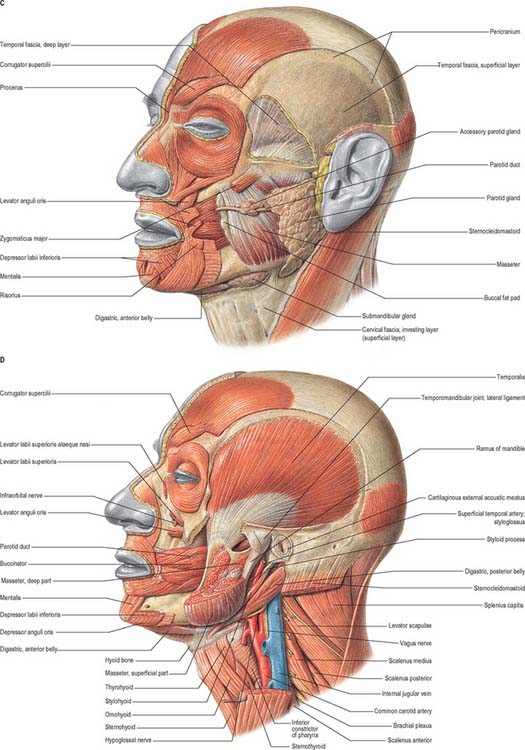

The parotid gland is surrounded by a fibrous capsule called the parotid fascia or capsule. Traditionally this has been described as an upward continuation of the investing layer of deep cervical fascia in the neck which splits to enclose the gland within a superficial and a deep layer. The superficial layer is attached above to the zygomatic process of the temporal bone, the cartilaginous part of the external acoustic meatus, and the mastoid process. The deep layer is attached to the mandible, and to the tympanic plate, styloid and mastoid processes of the temporal bone. The prevailing view is that the deep layer of the parotid gland is derived from the deep cervical fascia. However, the superficial layer of the parotid capsule appears to be continuous with the fascia associated with platysma, and is now regarded as a component of the SMAS (Mitz & Peyronie 1976; Wassef 1987; Gosain et al 1993). It varies in thickness from a thick fibrous layer anteriorly to a thin translucent membrane posteriorly. It may be traced forwards as a separate layer which passes over the masseteric fascia (itself derived from the deep cervical fascia), separated from it by a cellular layer which contains branches of the facial nerve and the parotid duct. Histologically, the parotid fascia is atypical in that it contains muscle fibres which parallel those of platysma, especially in the lower part of the parotid capsule. Although thin fibrous septa may be seen in the subcutaneous layer at the histological level, macroscopically there is little evidence of a distinct layer of superficial fascia.

The deep fascia covering the muscles forming the parotid bed (digastric and styloid group of muscles) contains the stylomandibular and mandibulostylohyoid ligaments. The stylomandibular ligament passes from the styloid process to the angle of the mandible. The more extensive mandibulostylohyoid ligament (angular tract) passes between the angle of the mandible and the stylohyoid ligament for varying distances, generally reaching the hyoid bone. It is thick posteriorly but thins anteriorly in the region of the angle of the mandible. There is some dispute as to whether the mandibulostylohyoid ligament is part of the deep cervical fascia (Ziarah & Atkinson 1981), or lies deep to it (Shimada & Gasser 1988). The stylomandibular and mandibulostylohyoid ligaments separate the parotid gland region from the superficial part of the submandibular gland, and so are landmarks of surgical interest.

BONES OF THE FACIAL SKELETON AND CRANIAL VAULT

The skull consists of the facial skeleton and cranial vault (calvarium) attached at the skull base. The cranial vault encloses and protects the brain. The facial skeleton is the anterior part of the skull and includes the mandible. The bones of the nasoethmoidal and zygomaticomaxillary complexes are described here. The mandible is described in Chapter 30.

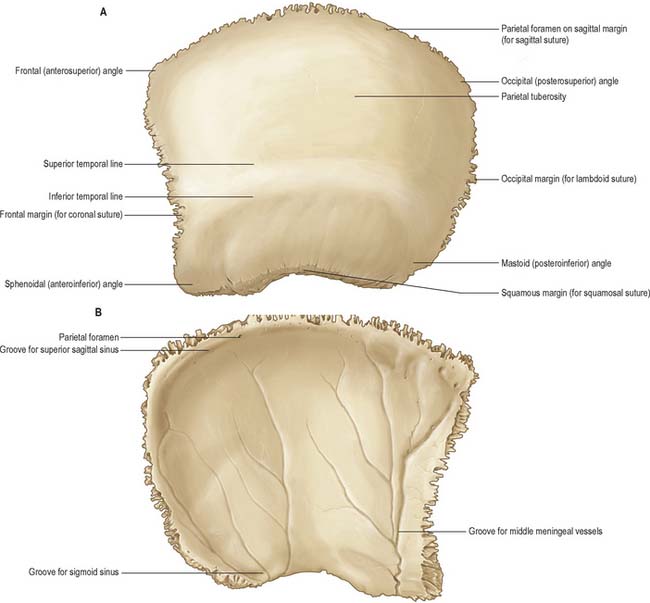

PARIETAL BONE

The two parietal bones form most of the cranial roof and sides of the skull. Each is irregularly quadrilateral and has two surfaces, four borders and four angles (Fig. 29.2).

The frontal (anterosuperior) angle, which is approximately 90°, is at the bregma, where sagittal and coronal sutures meet, and marks the site of the anterior fontanelle in the neonatal skull. The sphenoidal (anteroinferior) angle lies between the frontal bone and greater wing of the sphenoid. Its internal surface is marked by a deep groove or canal that carries the frontal branches of the middle meningeal vessels. The frontal, parietal, sphenoid and temporal bones usually meet at the pterion, which marks the site of the sphenoidal fontanelle in the embryonic skull. The frontal bone sometimes meets the squamous part of the temporal bone, in which case the parietal bone fails to reach the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The rounded occipital (posterosuperior) angle is at the lambda, the meeting of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, which marks the site of the posterior fontanelle in the neonatal skull. The blunt mastoid (posteroinferior) angle articulates with the occipital bone and the mastoid portion of the temporal bones at the asterion. Internally it bears a broad, shallow groove for the junction of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses.

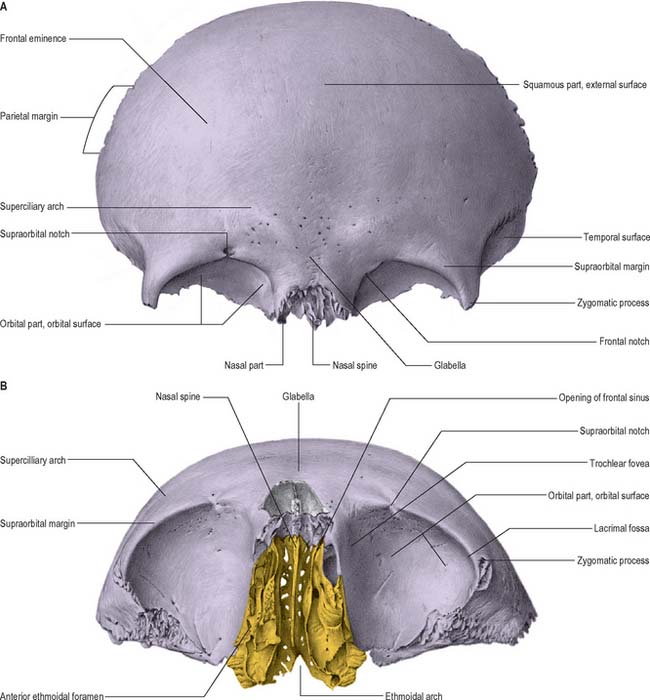

FRONTAL BONE

The frontal bone is like half a shallow, irregular cap forming the forehead or frons (Fig. 29.3). It has three parts, and contains two cavities, the frontal sinuses.

Squamous part

The internal surface of the frontal bone is concave. Its upper, median, part displays a vertical sulcus whose edges unite below as the frontal crest. The sulcus contains the anterior part of the superior sagittal sinus. The crest ends in a small notch which is completed by the ethmoid bone to form a foramen caecum. The anterior portion of the falx cerebri is attached to the margins of the sulcus and to the frontal crest. The internal surface shows impressions of cerebral gyri, small furrows for meningeal vessels, and granular foveolae for arachnoid granulations near the sagittal sulcus.

Orbital parts

The frontal sinuses are two irregular cavities that ascend posterolaterally for a variable distance between the frontal laminae. They are separated by a thin septum and usually deflected from the median plane, which means that they are rarely symmetrical. The sinuses are variable in size and usually larger in males. Their openings lie anterior to the ethmoidal notch and lateral to the nasal spine, and each communicates with the middle meatus in the ipsilateral nasal cavity by a frontonasal canal.

The frontal sinuses are rudimentary at birth and can barely be distinguished. They show a primary expansion with eruption of the first deciduous molars at about 18 months, and again when the permanent molars begin to appear in the sixth year. Growth is slow in the early years but it can be detected radiographically by 6 years. They reach full size after puberty, although with advancing age osseous absorption may lead to further enlargement. Their degree of development appears to be linked to the prominence of the superciliary arches, which is thought to be a response to masticatory stresses. The frontal sinuses are described in Chapter 32.

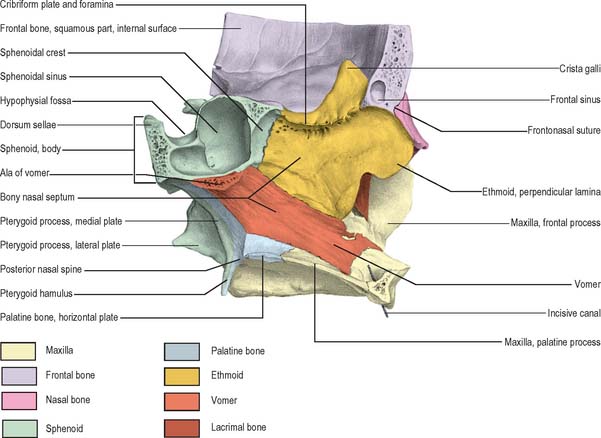

ETHMOID BONE

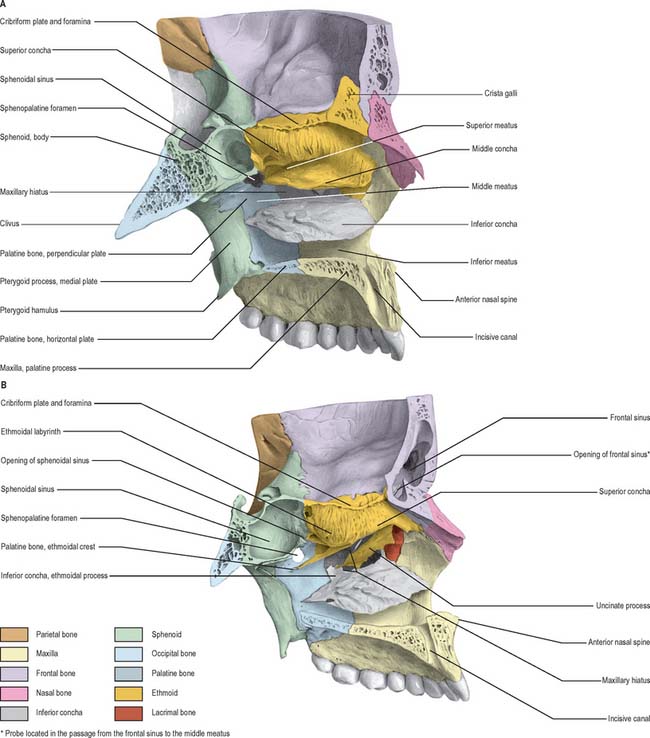

The ethmoid bone is cuboidal and fragile (Fig. 29.3B, Fig. 29.4, Fig. 29.5, Fig. 29.6). It lies anteriorly in the cranial base and contributes to the medial walls of the orbit, the nasal septum and the roof and lateral walls of the nasal cavity. It has a horizontal perforated cribriform plate, a median perpendicular plate, and two lateral labyrinths that contain the ethmoidal air cells.

Ethmoidal labyrinths

The medial surface of the labyrinth forms part of the lateral nasal wall. It appears as a thin lamella that descends from the inferior surface of the cribriform plate and ends as the convoluted middle nasal concha. Superiorly the surface contains numerous vertical grooves that transmit bundles of olfactory nerves. Posteriorly it is divided by the narrow, oblique superior meatus, bounded above by the thin, curved superior nasal concha. Posterior ethmoidal air cells open into the superior meatus. The convex surface of the middle nasal concha extends along the entire medial surface of the labyrinth, anteroinferior to the superior meatus. Its lower edge is thick and its lateral surface is concave and forms part of the middle meatus. Middle ethmoidal air cells produce a swelling, the bulla ethmoidalis, on the lateral wall of the middle meatus, and open into the meatus, either on the bulla or above it. A curved infundibulum extends up and forwards from the middle meatus and communicates with the anterior ethmoidal sinuses. In more than 50% of crania it continues up as the frontonasal duct to include the drainage point for the frontal sinus. (The ethmoidal air cells are described further in Chapter 32.)

Ossification

The ethmoid bone ossifies in the cartilaginous nasal capsule from three centres, one in the perpendicular plate, and one in each labyrinth. The latter two appear in the orbital plates between the fourth and fifth months in utero, and extend into the ethmoid conchae. At birth, the labyrinths, although ill-developed, are partially ossified, and the remainder are cartilaginous. The perpendicular plate begins to ossify from the median centre during the first year, and fuses with the labyrinths early in the second year. The cribriform plate is ossified partly from the perpendicular plate, and partly from the labyrinths. The crista galli ossifies during the second year. The parts of the ethmoid bone unite to form a single bone at around 3 years of age. Ethmoidal air cells begin to develop at about 3 months in utero, and are therefore present at birth, however, they are difficult to visualize radiographically until the end of the first year. They grow slowly and have almost reached adult size by the age of 12 years.

INFERIOR NASAL CONCHA

The inferior nasal conchae are curved horizontal laminae in the lateral nasal walls (Fig. 29.5) (see also Ch. 32). Each has two surfaces (medial and lateral), two borders (superior and inferior) and two ends (anterior and posterior). The medial surface is convex, much perforated, and longitudinally grooved by vessels. The lateral surface is concave and part of the inferior meatus. The superior border, thin and irregular, may be divided into three regions: an anterior region articulating with the conchal crest of the maxilla; a posterior region articulating with the conchal crest of the palatine bone; and a middle region with three processes, which are variable in size and form. The lacrimal process is small and pointed and lies towards the front. It articulates apically with a descending process from the lacrimal bone, and at its margins with the edges of the nasolacrimal groove on the medial surface of the maxilla, thereby helping to complete the nasolacrimal canal. Most posteriorly, a thin ethmoidal process ascends to meet the uncinate process of the ethmoid bone. An intermediate thin maxillary process curves inferolaterally to articulate with the medial surface of the maxilla at the opening of the maxillary sinus. The inferior border is thick and spongiose, especially in its midpart. Both the anterior and posterior ends of the inferior nasal concha are more or less tapered, the posterior more than the anterior.

LACRIMAL BONE

The lacrimal bones are the smallest and most fragile of the cranial bones and lie anteriorly in the medial walls of the orbits (Fig. 29.5B). Each has two surfaces (medial and lateral) and four borders (anterior, posterior, superior and inferior). The lateral (orbital) surface is divided by a vertical posterior lacrimal crest. Anterior to the crest is a vertical groove whose anterior edge meets the posterior border of the frontal process of the maxilla to complete the fossa that houses the lacrimal sac. The medial wall of the groove is prolonged by a descending process that contributes to the formation of the nasolacrimal canal by joining the lips of the nasolacrimal groove of the maxilla and the lacrimal process of the inferior nasal concha. A smooth part of the medial orbital wall lies behind the posterior lacrimal crest: the lacrimal part of orbicularis oculi is attached to this surface and crest. The surface ends below in the lacrimal hamulus which, together with the maxilla, completes the upper opening of the nasolacrimal canal. The hamulus may appear as a separate lesser lacrimal bone. The anteroinferior region of the medial (nasal) surface is part of the middle meatus. Its posterosuperior part meets the ethmoid to complete some of the anterior ethmoidal air cells. The anterior border of the lacrimal bone articulates with the frontal process of the maxilla, the posterior border with the orbital plate of the ethmoid bone, the superior border with the frontal bone, and the inferior border with the orbital surface of the maxilla.

NASAL BONE

The nasal bones are small, oblong, variable in size and form, and placed side by side between the frontal processes of the maxillae (Fig. 29.4, Fig. 29.5, Fig. 29.6B). They jointly form the nasal bridge. Each nasal bone has two surfaces (external and internal) and four borders (superior, inferior, lateral and mesial). The external surface has a descending concavo-convex profile and is transversely convex. It is covered by procerus and nasalis and perforated centrally by a small foramen that transmits a vein. The internal surface, transversely concave, bears a longitudinal groove that houses the anterior ethmoidal nerve. The superior border, thick and serrated, articulates with the nasal part of the frontal bone. The inferior border, thin and notched, is continuous with the lateral nasal cartilage. The lateral border articulates with the frontal process of the maxilla. The medial border, thicker above, articulates with its fellow and projects behind as a vertical crest, thereby forming a small part of the nasal septum. It articulates from above with the nasal spine of the frontal bone, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, and the nasal septal cartilage.

VOMER

The vomer is thin, flat, and almost trapezoid (Fig. 29.4). It forms the posteroinferior part of the nasal septum and presents two surfaces and four borders. Both surfaces are marked by grooves for nerves and vessels. A prominent groove for the nasopalatine nerve and vessels lies obliquely in an anteroinferior plane. The superior border is thickest, and possesses a deep furrow between projecting alae which fits the rostrum of the body of the sphenoid bone. The alae articulate with the sphenoidal conchae, the vaginal processes of the medial pterygoid plates of the sphenoid bone, and the sphenoidal processes of the palatine bones. Where each ala lies between the body of the sphenoid and the vaginal process, its inferior surface helps to form the vomerovaginal canal. The inferior border articulates with the median nasal crests of the maxilla and palatine bones. The anterior border is the longest, and articulates in its upper half with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. Its lower half is cleft to receive the inferior margin of the nasal septal cartilage (see Ch. 32). The concave posterior border is thick and bifid above and thin below: it separates the posterior nasal apertures. The anterior extremity of the vomer articulates with the posterior margin of the maxillary incisor crest and descends between the incisive canals.

ZYGOMATIC BONE

Each zygomatic bone forms the prominence of a cheek, contributes to the floor and lateral wall of the orbit and the walls of the temporal and infratemporal fossae, and completes the zygomatic arch. Each is roughly quadrangular and is described as having three surfaces, five borders and two processes (Fig. 29.7).

Fig. 29.7 Zygomatic bone. A, Anterolateral aspect. B, Posterolateral aspect. Muscle attachments shown in A.

The frontal process, thick and serrated, articulates above with the zygomatic process of the frontal bone and behind with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. A tubercle of varying size and form, Whitnall’s tubercle, is usually present on its orbital aspect, within the orbital opening and about 1 cm below the frontozygomatic suture. This tubercle provides attachment for the lateral palpebral ligament, the suspensory ligament of the eye, and part of the aponeurosis of levator palpebrae superioris. The temporal process, directed backwards, has an oblique, serrated end that articulates with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to complete the zygomatic arch.

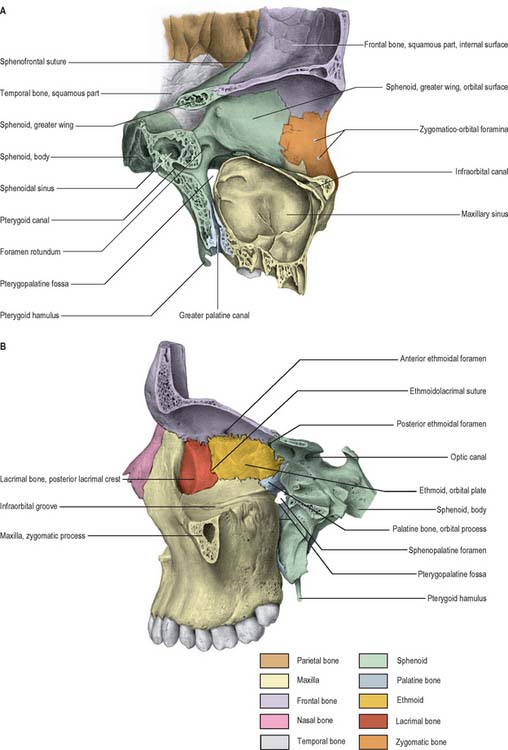

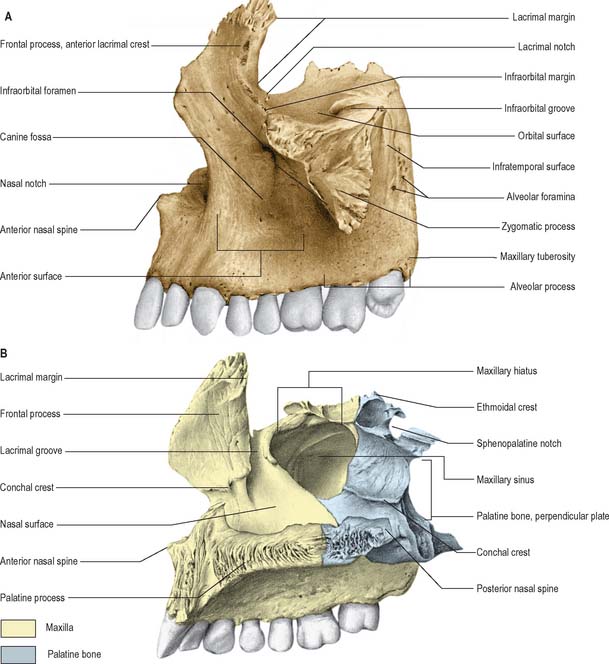

MAXILLA

The maxillae are the largest of the facial bones, other than the mandible, and jointly form the whole of the upper jaw. Each bone forms the greater part of the floor and lateral wall of the nasal cavity, and of the floor of the orbit, contributes to the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossae, and bounds the inferior orbital and pterygomaxillary fissures. Each maxilla has a body and four processes, namely the zygomatic, frontal, alveolar and palatine processes (Fig. 29.6, Fig. 29.8).

Body

Frontal process

The frontal process projects posterosuperiorly between the nasal and lacrimal bones. Its lateral surface is divided by a vertical anterior lacrimal crest which gives attachment to the medial palpebral ligament and is continuous below with the infraorbital margin. A small palpable tubercle at the junction of the crest and orbital surface is a guide to the lacrimal sac. The smooth area anterior to the lacrimal crest merges below with the anterior surface of the body of the maxilla. Parts of orbicularis oculi and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi are attached here. Behind the crest, a vertical groove combines with a groove on the lacrimal bone to complete the lacrimal fossa. The medial surface is part of the lateral nasal wall. A rough subapical area articulates with the ethmoid, and closes anterior ethmoidal air cells. Below this an oblique ethmoidal crest articulates posteriorly with the middle nasal concha, and anteriorly underlies the agger nasi, a ridge anterior to the concha on the lateral nasal wall. The ethmoidal crest forms the upper limit of the atrium of the middle meatus. The frontal process articulates above with the nasal part of the frontal bone. Its anterior border articulates with the nasal bone and its posterior border articulates with the lacrimal bone.

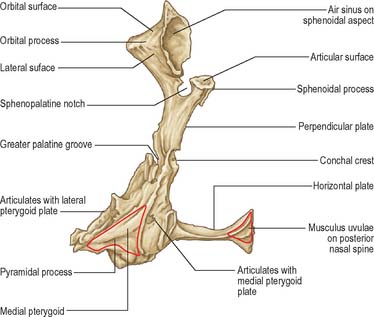

PALATINE BONE

The palatine bones are posteriorly placed in the nasal cavity, between the maxillae and the pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bones. They contribute to the floor and lateral walls of the nose, to the floor of the orbit and the hard palate, to the pterygopalatine and pterygoid fossae, and to the inferior orbital fissures. Each has two plates (horizontal and perpendicular) arranged as an L-shape, and three processes (pyramidal, orbital and sphenoidal) (Fig. 29.9).

Orbital process

Of the non-articular surfaces, the triangular superior (orbital) surface is directed superolaterally to the posterior part of the orbital floor. The lateral surface is oblong, faces the pterygopalatine fossa and is separated from the orbital surface by a rounded border that forms a medial part of the lower margin of the inferior orbital fissure. This surface may present a groove, directed superolaterally, for the maxillary nerve, and is continuous with the groove on the upper posterior surface of the maxilla. The border between the lateral and posterior surfaces descends anterior to the sphenopalatine notch.

FRACTURES OF THE FACIAL SKELETON

Upper third of face

Fractures in the upper third of the face are almost invariably comminuted and are often associated with fractures of the middle third of the face. Fractures of the frontal bone may involve the frontal sinuses and/or orbital roof. If the frontonasal duct is traumatized its drainage may be impaired, which predisposes to ascending intracranial infection and mucocele development within the frontal sinuses. This risk may be minimized with frontonasal stents or frontonasal duct and frontal sinus obliteration with autogenous bone graft (see Ch. 32). Fractures that involve both the anterior and posterior walls of the frontal sinus also carry a risk of early and delayed intracranial infection, and often it is necessary to obliterate the frontal sinuses or cranialize the frontal sinuses in order to prevent this complication. Cranialization of the frontal sinuses involves the removal of the posterior wall and all frontal sinus mucosa, typically through a frontal craniotomy approach. Fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus may be associated with dural tears (and cerebrospinal rhinorrhoea) which must be repaired at the same time. Fractures involving the orbital roof may be associated with displacement of the globe of the eye, diplopia and supraorbital nerve injury.

Middle third of the face

Central middle third of the face

Complex nasal injuries may include nasofrontal suture disjunction, nasolacrimal and frontonasal duct injury and fracture of the ethmoid complex. The skeletal foundation of the nasoethmoidal complex consists of a strong triangular-shaped frame. However, all these structures are fragile and any force sufficient to fracture the frame results in severe comminution and displacement. The ethmoid air cells act as a crumple zone protecting the skull base from mechanical forces. A severe impact delivered to the midface, particularly over the bridge of the nose, may result in these structures being driven backwards between the orbits. This may result in traumatic hypertelorism, producing an increase in distance between the pupils. Associated displacement of the medial canthal ligaments results in traumatic telecanthus. Increased intercanthal distance (normal range 24–39 mm in Caucasians) may be corrected using microplates, stainless steel wire and acrylic canthal splints. Damage to the lacrimal system requires approximation of the severed canalicular ends or dacrocystorhinostomy. Comminution of the cribriform plates of the ethmoid may result in dural tears and cerebrospinal rhinorrhoea. Often nasoethmoidal fractures are combined with more extensive fractures of the frontal bone. The complexity of the injury has implications for subsequent facial reconstruction.

Lower third of face (mandible)

The mandible is essentially a tubular bone bent into a blunt V-shape (see Ch. 30). This basic configuration is modified by sites of muscle attachment, principally masseter and medial pterygoid at the angle, and temporalis at the coronoid process. The presence of teeth, particularly those with long roots such as the canines, or of unerupted teeth, produces lines of weakness in the mandible. When the teeth are lost, or fail to develop, the subsequent progressive resorption of the alveolar bone means that the mandible reverts to its underlying tubular structure. Like all tubular bones, the strength of the mandible resides in a dense cortical plate, thickened anteriorly and at its lower border: it follows that the mandible is strongest anteriorly in the midline and is progressively weaker posteriorly towards the condylar processes. Again, like all tubular bones, the mandible has great resistance to compressive forces, but fractures at sites of tensile strain. It is liable to particular patterns of distribution of tensile strain when forces are applied to it. Anterior forces applied to the mental symphysis, or over the body of the mandible, lead to strain at the condylar necks and also along the lingual cortical plates on the contralateral side in the molar region. The mandible therefore often fractures at two sites and isolated fractures are relatively unusual. In order of frequency, fractures occur most commonly at the neck of the condyle, the angle, the parasymphysial region and the body of the mandible.

MUSCLES OF THE FACE

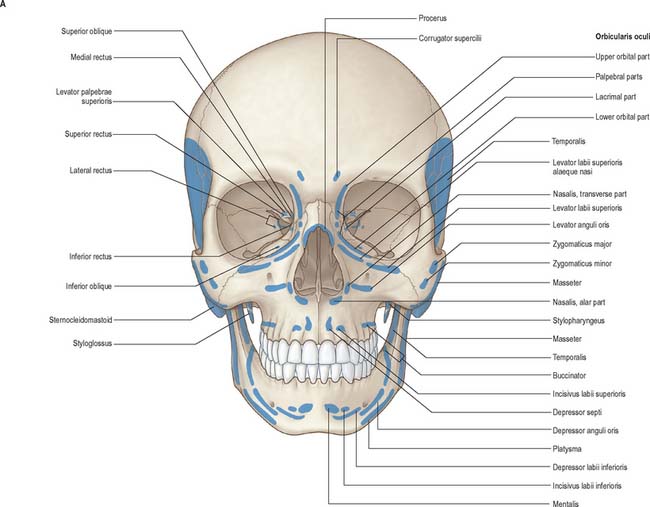

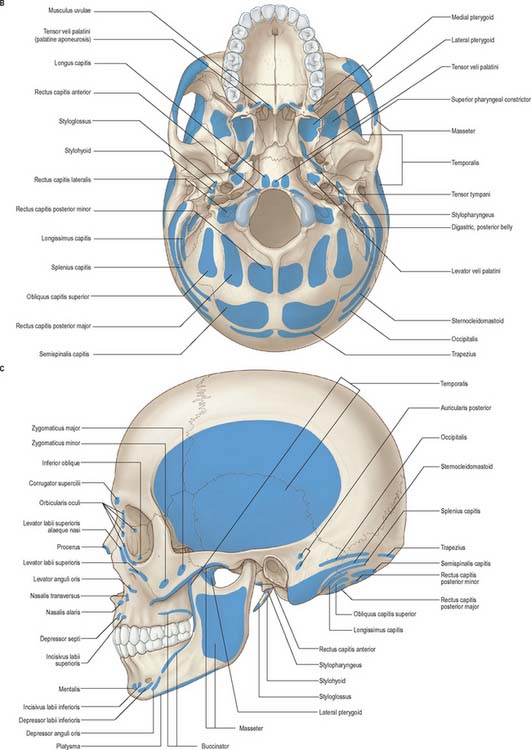

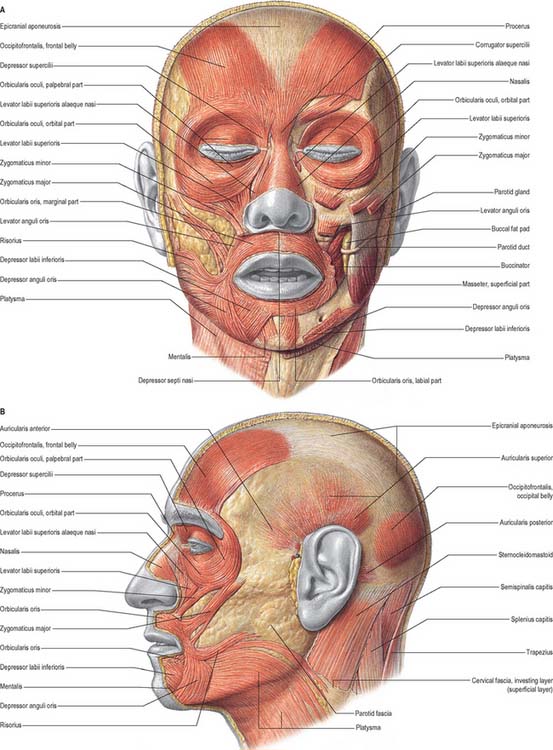

Craniofacial muscles are associated with the orbital margins and eyelids, external nose and nostrils, lips, cheeks and mouth, pinna, scalp and cervical skin, and collectively are often called, not very accurately, ‘muscles of facial expression’ (Fig. 29.10). Their organization differs from that of muscles in most other regions of the body because there is no deep membranous fascia beneath the skin of the face, and many small slips of muscle that are attached to the facial skeleton insert directly into the skin.

Although these muscles produce movements of the facial skin that reflect emotions, it is usually argued that their primary function is to act as sphincters and dilators of the facial orifices and that the function of facial expression has developed secondarily. Embryologically, they are derived from the mesenchyme of the second branchial arch and so are innervated by the facial nerve. Topographically and functionally the muscles of facial expression may be subdivided into epicranial, circumorbital and palpebral, nasal, and buccolabial groups (Fig. 29.11).

EPICRANIAL MUSCLE GROUP

Epicranius

Epicranius consists of occipitofrontalis and temporoparietalis.

Epicranial aponeurosis

The epicranial aponeurosis covers the upper part of the cranium and, with the epicranial muscle, forms a continuous fibromuscular sheet that extends from the occiput to the eyebrows. Posteriorly, between the occipital parts of occipitofrontalis, it is attached to the external protuberance and highest nuchal line of the occipital bone. Anteriorly it splits to enclose the frontal parts and sends a short narrow prolongation between them. Laterally, the anterior and superior auricular muscles are attached to it; the aponeurosis is thinner, and continues over the temporal fascia to the zygomatic arch. It is united to the skin lying over the cranial vault by fibrous superficial fascia, but it is connected more loosely to the underlying pericranium by areolar tissue, an arrangement that allows it to move freely, carrying with it the skin of the scalp.

CIRCUMORBITAL AND PALPEBRAL MUSCLE GROUP

The circumorbital and palpebral group of muscles are orbicularis oculi, corrugator supercilii and levator palpebrae superioris. The first two are described here; levator palpebrae superioris is described in Chapter 39.

Orbicularis oculi

Orbicularis oculi is the sphincter muscle of the eyelids and plays an important role in facial expression and various ocular reflexes. The orbital portion is usually activated under voluntary control. Contraction of the upper orbital fibres produces vertical furrowing above the bridge of the nose, narrowing of the palpebral fissure, and bunching and protrusion of the eyebrows, which reduces the amount of light entering the eyes. Eye closure is largely affected by lowering of the upper eyelid, but there is also considerable elevation of the lower eyelid. The palpebral portion can be contracted voluntarily, to close the lids gently as in sleep, or reflexly, to close the lids protectively in blinking. The palpebral part has upper depressor and lower elevator fascicles. The lacrimal part of the muscle draws the eyelids and the lacrimal papillae medially, thereby exerting traction on the lacrimal fascia, and may aid drainage of tears by dilating the lacrimal sac. It may also influence pressure gradients within the lacrimal gland and ducts. This activity may assist in the sinuous flow of tears across the cornea, direct the lacrimal punctum into the lacus lacrimalis, and express secretions of the ciliary and tarsal glands. When the entire orbicularis oculi muscle contracts, the skin is thrown into folds which radiate from the lateral angle of the eyelids. Such folds, when permanent, cause wrinkles in middle age (the so-called ‘crow’s feet’).

NASAL MUSCLE GROUP

The nasal muscle group, which consists of procerus, nasalis and depressor septi, is described in Chapter 32.

BUCCOLABIAL MUSCLE GROUP

Levator labii superioris alaequae nasi

Levator labii superioris alaequae nasi is described in Chapter 32.

Levator labii superioris

Zygomaticus minor

Levator anguli oris

Depressor labii inferioris

Depressor labii inferioris is a quadrilateral muscle that arises from the oblique line of the mandible, between the symphysis menti and the mental foramen. It passes upwards and medially into the skin and mucosa of the lower lip, blending with its contralateral fellow and with orbicularis oris. Below and laterally it is continuous with platysma.

Depressor anguli oris

Orbicularis oris

Pars marginalis

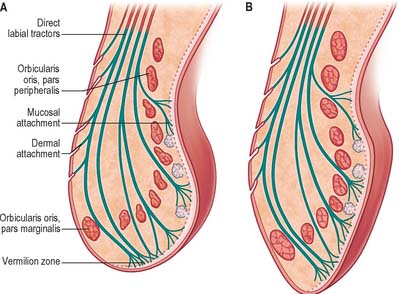

Pars marginalis of orbicularis oris is developed to a unique extent in human lips and is closely associated with speech and the production of some kinds of musical tone. In each quadrant the pars marginalis consists of a single (occasionally double) band of narrow diameter muscle fibres lodged within the tissues of each vermilion zone. At their medial end, the marginal fibres meet and interlace with their contralateral fellows and then attach to the dermis of the vermilion zone a few millimetres beyond the median plane in a manner similar to pars peripheralis. At their lateral ends, the fibres converge and attach to the deepest part of the modiolar base along a horizontal strip level with the buccal angle.

Platysma

Platysma is described as a muscle of the neck (see Ch. 28) but it is considered here as a contributor to the orbicularis oris muscle complex. It has mandibular, labial and modiolar parts. Pars mandibularis attaches to the lower border of the body of the mandible. Posterior to this attachment, a substantial flattened bundle separates and passes superomedially to the lateral border of depressor anguli oris, where a few fibres join this muscle. The remainder continue deep to depressor anguli oris and reappear at its medial border. Here they continue within the tissue of the lateral half of the lower lip, as a direct labial tractor, platysma pars labialis. Pars labialis occupies the interval between depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris and is in the same plane as these muscles. The adjacent margins of all three muscles blend and they have similar labial attachments. Platysma pars modiolaris constitutes all the remaining bundles posterior to pars labialis, other than a few fine fascicles that end directly in buccal dermis or submucosa. Pars modiolaris is posterolateral to depressor anguli oris and passes superomedially, deep to risorius, to apical and subapical modiolar attachments.

MOVEMENTS OF THE FACE AND LIPS

Direct labial tractors

In both upper and lower lips the tractors blend into a continuous sheet that divides into a series of superimposed coronal sheets which are anterior to the muscle bundles of pars peripheralis orbicularis oris as they enter the free lip. The sheets may be divided into three groups at increasing depths from the skin surface, each with a distinct zone of attachment (Fig. 29.12). The superficial group comprises a succession of fine fibre bundles which curve anteriorly a short distance before attaching in a series of horizontal rows to the dermis between the hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands. The intermediate group attaches to the dermis of the vermilion zone, which they reach by two routes: the more superficial bundles continue past the skin/vermilion junction, then curve posteriorly over pars marginalis orbicularis oris to punctate attachments on the ventral half of the dermis of the vermilion zone, while the deeper bundles first pass posteriorly between pars peripheralis and pars marginalis, then curve anteriorly to punctate attachments on the dorsal half of the dermis of the vermilion zone. The deep group is closely applied to the anterior surface of pars peripheralis orbicularis oris, and sends fine tractor fibres between its parallel bundles to attach posteriorly into the submucosa and periglandular connective tissue.

Movements of the lips

Lip protrusion is passive in its initial stages. It may be suppressed by powerful contraction of the whole of orbicularis oris or enhanced by selective activation of parts of the direct labial tractors. However, lip movements must accommodate separation of the teeth brought about by mandibular depression at the temporomandibular joints. Beyond a certain range of mouth opening, labial movements are almost completely dominated by mandibular movements. Thus over the last 2.5–3 cm interincisal distance of wide jaw separation, strong contraction of orbicularis oris cannot effect lip contact, and instead it causes full-thickness inflection of upper and lower lips, including the vermilion zone, towards the oral cavity, wrapping them around the incisal edges, canine cusps and premolar occlusal surfaces. The involvement of the lips in speech is described in Chapter 34, but some aspects relevant to the actions of orbicularis oris pars marginalis will be described here. Contraction of marginalis is considered to alter the cross-sectional profile of the free margin of the vermilion zone such that both the gentle bulbous profile of the upper lip and the smooth posterosuperior convexity of the lower lip change to a narrow, symmetrical triangular profile. The transformed rims, whose length and tension can be delicately controlled, have been named labial cords. They are known to be involved in the production of some consonantal (labial) sounds. A labial cord may also function as a ‘vibrating reed’ in whistling or playing a wind instrument such as the trumpet.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

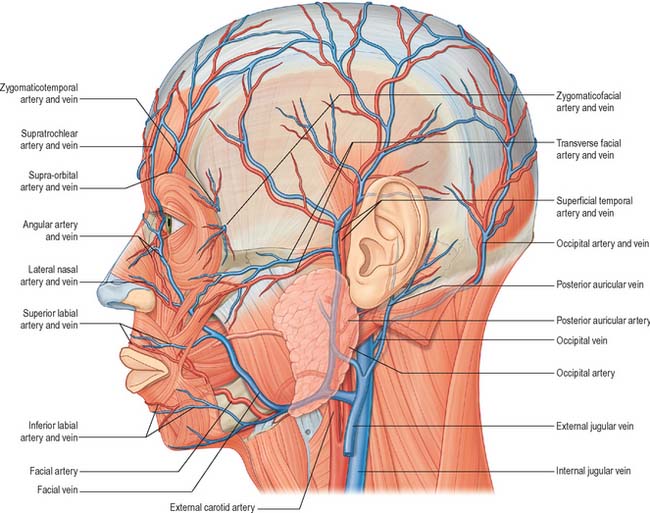

ARTERIAL SUPPLY TO THE FACE

The main arterial supply to the face is derived from the facial and superficial temporal arteries, with additional supply from branches of the maxillary and ophthalmic arteries. The back of the scalp is supplied by the posterior auricular and occipital arteries. There are numerous anastomoses between the branches.

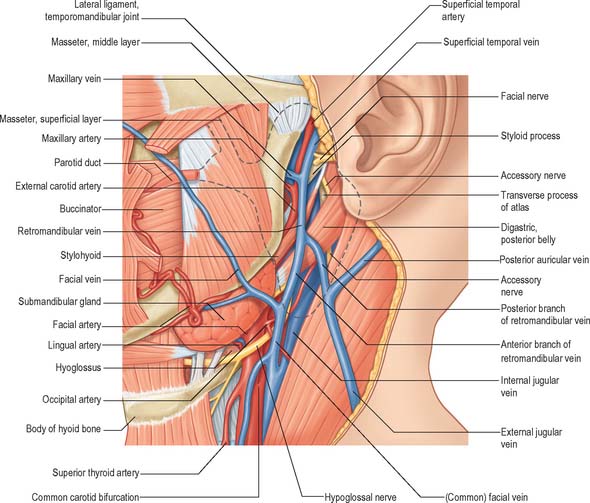

Facial artery

The facial artery arises in the neck from the external carotid artery (see Ch. 28). It initially lies beneath platysma, passing onto the face at the anteroinferior border of masseter, where its pulse can be felt as it crosses the mandible. The artery is deep to skin, the fat of the cheek and, near the angle of the mouth, zygomaticus major and risorius, and superficial to buccinator and levator anguli oris. It may pass over or through levator labii superioris, and pursues a tortuous course along the side of the nose towards the medial corner of the eye. At its termination it is embedded in levator labii superioris alaequae nasi.

The facial artery supplies branches to the muscles and skin of the face (Fig. 29.13). Its named branches on the face are the premasseteric artery, the superior and inferior labial arteries and the lateral nasal artery. The part of the artery distal to its terminal branch is called the angular artery.

Fig. 29.13 The arteries and veins of the left side of the face, head and neck and their main branches. The infraorbital artery is shown in Fig. 25.1.

Superficial temporal artery

The transverse facial artery arises before the superficial temporal artery emerges from the parotid gland. It traverses the gland, crosses masseter between the parotid duct and the zygomatic arch (accompanied by one or two facial nerve branches) and divides into numerous branches that supply the parotid gland and duct, masseter and adjacent skin. The branches anastomose with the facial, masseteric, buccal, lacrimal and infraorbital arteries, and may have a direct origin from the external carotid artery.

Occipital artery

The occipital artery arises in the neck from the external carotid artery (see Ch. 28). It runs in a groove on the temporal bone, medial to the mastoid process. Accompanied by the greater occipital nerve, the occipital artery enters the back of the scalp by piercing the investing layer of deep cervical fascia that connects the cranial attachments of trapezius and sternocleidomastoid. Tortuous branches run between the skin and the occipital belly of occipitofrontalis, anastomosing with the opposite occipital, posterior auricular and superficial temporal arteries as well as with the transverse cervical branch of the subclavian artery. These branches supply the occipital belly of occipitofrontalis and the skin and pericranium associated with the scalp as far forward as the vertex. The artery may give off a meningeal branch which traverses the parietal foramen.

VEINS OF THE FACE

The veins of the face are subject to considerable variations: the following description concerns those that are relatively constant (Fig. 29.13).

Supraorbital vein

The supraorbital vein begins near the zygomatic process of the frontal bone, connecting with branches of the superficial and middle temporal veins. It passes medially above the orbital opening, pierces orbicularis oculi and unites with the supratrochlear vein near the medial canthus of the eye to form the facial vein. A branch passes through the supraorbital notch, where it receives veins from the frontal sinus and frontal diploë, and subsequently connects with the superior ophthalmic vein.

Facial vein

The facial vein is the main vein of the face. After receiving the supratrochlear and supraorbital veins, it travels obliquely downwards by the side of the nose, passes under zygomaticus major, risorius and platysma, descends to the anterior border and then passes over the surface of masseter. It crosses the body of the mandible, and runs down in the neck to drain into the internal jugular vein. The facial vein initially lies behind the more tortuous facial artery, but crosses the artery at the lower border of the mandible. The uppermost segment of the facial vein, above its junction with the superior labial vein, is also called the angular vein: any infection of the mouth or face can spread via the angular veins to the cavernous sinuses resulting in thrombosis (see Ch. 27).

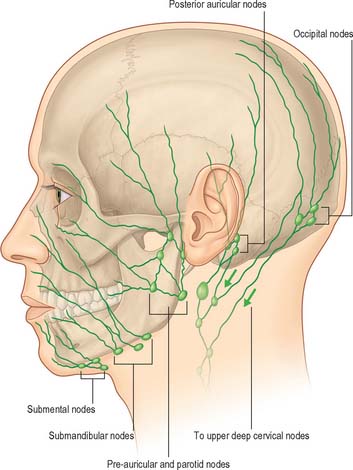

LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE OF THE FACE AND SCALP

Lymph vessels from the frontal region above the root of the nose drain to the submandibular nodes (Fig. 29.14; see Fig. 28.15). Vessels from the rest of the forehead, temporal region, upper half of the lateral auricular aspect and anterior wall of the external acoustic meatus drain to the superficial parotid nodes, which lie just anterior to the tragus, either on or deep to the parotid fascia. These nodes also drain lateral vessels from the eyelids and skin of the zygomatic region, and their efferent vessels pass to the upper deep cervical nodes. A strip of scalp above the auricle, the upper half of the cranial aspect and margin of the auricle, and the posterior wall of the external acoustic meatus all drain to the upper deep cervical and posterior auricular nodes. The posterior auricular nodes are superficial to the mastoid attachment of sternocleidomastoid and deep to auricularis posterior, and drain to the upper deep cervical nodes. The auricular lobule, floor of the external acoustic meatus and skin over the mandibular angle and lower parotid region all drain to the superficial cervical or upper deep cervical nodes. Superficial cervical nodes lie along the external jugular vein superficial to sternocleidomastoid. Some efferents pass round the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid to the upper deep cervical nodes, others follow the external jugular vein to the lower deep cervical nodes in the subclavian triangle.

INNERVATION

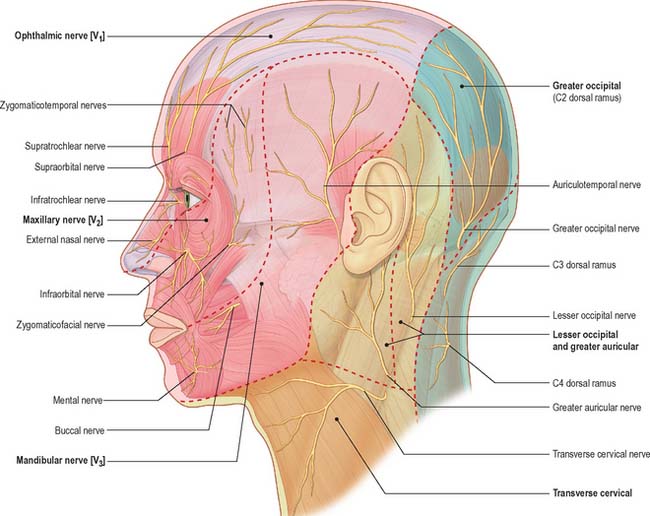

The numerous muscles of facial expression are supplied by the facial nerve, while the two muscles of mastication that relate to the face are innervated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The sensory innervation is primarily from the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve, with smaller contributions from the cervical spinal nerves. The detailed innervation of the auricle is considered on p. 620.

TRIGEMINAL NERVE

Three large areas of the face can be mapped out to indicate the peripheral nerve fields associated with the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve. The fields are not horizontal but curve upwards (Fig. 29.15), apparently because the facial skin moves upwards with growth of the brain and skull. Embryologically, each division of the trigeminal nerve is associated with a developing facial process which gives rise to a specific area of the adult face: the ophthalmic nerve is associated with the frontonasal process, the maxillary nerve with the maxillary process, and the mandibular nerve with the mandibular process.

Fig. 29.15 Cutaneous innervation of the face and neck, showing dermatomes (in bold).

(Adapted from Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

Maxillary nerve

Zygomaticotemporal nerve

The zygomaticotemporal nerve traverses a canal in the zygomatic bone and emerges into the anterior part of the temporal fossa, where it ascends between the bone and temporalis before piercing the temporal fascia about 2 cm above the zygomatic arch to supply the skin of the temple. It communicates with the facial and auriculotemporal nerves. As it pierces the deep layer of the temporal fascia it sends a slender twig between the two layers of the fascia towards the lateral angle of the eye: the branch carries parasympathetic postganglionic fibres from the pterygopalatine ganglion to the lacrimal gland.

Mandibular nerve

Mental nerve

The mental nerve is the terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve (see Ch. 30). It enters the face through the mental foramen, where it is directed backwards, and supplies the skin of the lower lip and labial gingivae. Occasionally the mental nerve is important aetiologically in the pain of trigeminal neuralgia, and it is amenable to cryotherapy surgery.

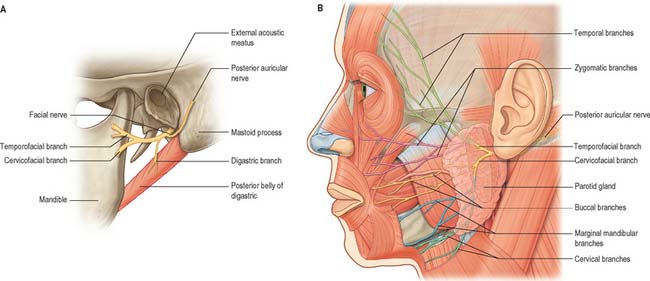

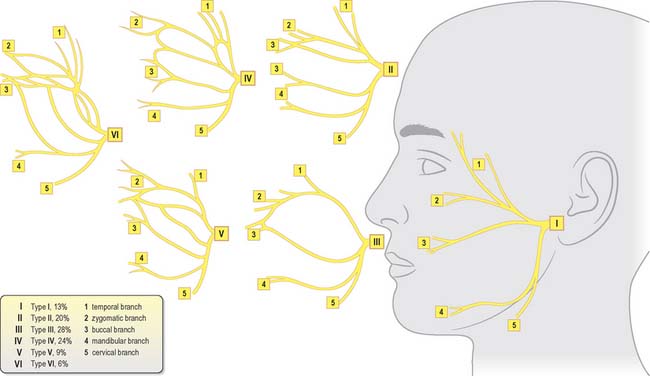

FACIAL NERVE

The facial nerve emerges from the base of the skull at the stylomastoid foramen and almost immediately gives off the nerves to the posterior belly of digastric and stylohyoid, and the posterior auricular nerve, which supplies the occipital belly of occipitofrontalis and some of the auricular muscles (Fig. 29.16A).

The nerve next enters the parotid gland high up on its posteromedial surface and passes forwards and downwards behind the mandibular ramus. Within the substance of the gland it branches into superior (temporofacial) and inferior (cervicofacial) trunks, usually just behind and superficial to the retromandibular vein. The trunks branch further to form a parotid plexus (pes anserinus). Five main terminal branches arise from the plexus, they diverge within the gland and leave by its anteromedial surface, medial to its anterior margin, to supply the muscles of facial expression (Fig. 29.16B). Six distinctive anastomotic patterns were originally classified by Davis et al (1956) and these are illustrated in Fig. 29.17. Numerous microdissection studies have demonstrated that branching patterns and anastomoses between branches, both within the parotid and on the face, exhibit considerable individual variation (e.g. Lineaweaver et al 1997; Kwak et al 2004): the account that follows is therefore an overview. In surgical terms these anastomoses are important, and presumably explain why accidental or deliberate division of a small branch often fails to result in the expected facial nerve weakness. The surface anatomy of the facial nerve is described in Chapter 25.

Fig. 29.17 Pattern of branching of the facial nerve.

(Modified with permission from Berkovitz BKB, Moxham BJ 2002 Head and Neck Anatomy. London: Martin Dunitz, and from Davis RA, Anson BJ, Budinger JM, Kurth IE 1956 Surgical anatomy of the facial nerve and parotid gland based upon a study of 350 cervicofacial halves. Surg Gynecol Obstet 102: 385–412, with permission from the American College of Surgeons.)

Zygomatic branches are generally multiple. They cross the zygomatic bone to the lateral canthus of the eye and supply orbicularis oculi: they may also supply muscles innervated by the buccal branch. Twigs communicate with filaments of the lacrimal nerve and the zygomaticofacial branch of the maxillary nerve.

There are usually two marginal mandibular branches. They run forwards towards the angle of the mandible under platysma, then turn upwards across the body of the mandible to pass under depressor anguli oris. The branches supply risorius and the muscles of the lower lip and chin, and filaments communicate with the mental nerve. The marginal mandibular branch has an important surgical relationship with the lower border of the mandible (see Ch. 25).

Cervical spinal nerves

Cervical spinal nerves have cutaneous branches which supply areas of skin in the face and scalp (Fig. 29.15). The named branches are the great auricular and lesser occipital nerves, which are part of the cervical plexus, and are described on page 435 (see Fig. 28.1) and the greater occipital nerve which is described on page 755 (see Fig. 42.52, Fig. 43.6).

PAROTID SALIVARY GLAND

The paired parotid glands are the largest of the salivary glands. Each has an average weight of 25 g and is an irregular, lobulated, yellowish mass, lying largely below the external acoustic meatus between the mandible and sternocleidomastoid. The gland also projects forwards onto the surface of masseter (Fig. 29.16B). In 20% of cases, a small, usually detached, part called the accessory parotid gland (pars accessoria or socia parotidis) lies between the zygomatic arch above and the parotid duct below. The overall shape of the parotid gland is variable. Viewed laterally, in 50% of cases it is roughly triangular in outline. However in 30% of cases the gland is more or less of even width throughout, and the upper and lower poles are rounded.

In its usual inverted pyramidal form, the parotid gland presents a small superior surface, and superficial, anteromedial and posteromedial surfaces. It tapers inferiorly to a blunt apex. The concave superior surface is related to the cartilaginous part of the external acoustic meatus and posterior aspect of the temporomandibular joint. Here the auriculotemporal nerve curves round the neck of the mandible, embedded in the capsule of the gland. The apex overlaps the posterior belly of digastric and the carotid triangle to a variable extent.

The posteromedial surface is moulded to the mastoid process, sternocleidomastoid, posterior belly of the digastric, and the styloid process and its associated muscles. The external carotid artery grooves this surface before entering the gland, and the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein are separated from the gland by the styloid process and its associated muscles (Fig. 29.18). The anteromedial and posteromedial surfaces meet at a medial margin that may project so deeply that it contacts the lateral wall of the pharynx.

STRUCTURES WITHIN THE PAROTID GLAND

The external carotid artery, retromandibular vein and facial nerve, either in part or in whole, traverse the gland and branch within it. The external carotid artery enters the posteromedial surface, and divides into the maxillary artery, which emerges from the anteromedial surface, and the superficial temporal artery, which gives off its transverse facial branch in the gland and ascends to leave its upper limit (Fig. 29.16). The posterior auricular artery may also branch from the external carotid artery within the gland, leaving by its posteromedial surface.

PAROTID DUCT

The average dimensions of the parotid duct are 5 cm long and 3 mm wide (although it is narrower at its oral orifice). It begins by the confluence of two main tributaries within the anterior part of the parotid gland: the duct appears at the anterior border of the upper part of the gland and passes horizontally across masseter, approximately midway between the angle of the mouth and the zygomatic arch (Fig. 29.16). If the duct arises lower down, it may run obliquely upwards. It crosses masseter, turns medially at its anterior border at almost a right angle, and traverses the buccal fat pad and buccinator opposite the crown of the upper third molar tooth. The duct then runs obliquely forwards for a short distance between buccinator and the oral mucosa before it opens upon a small papilla opposite the second upper molar crown. The submucosal passage of the duct serves as a valvular mechanism preventing inflation of the gland with raised intraoral pressures. While crossing masseter, the duct lies between the upper and lower buccal branches of the facial nerve, and may receive the accessory parotid duct.

The ramifications of the ductal systems, and their patterns and calibres, can be demonstrated radiographically by injecting a radio-opaque substance into the parotid duct via a cannula. In a lateral parotid sialogram the main duct can be seen to be formed near the centre of the posterior border of the mandibular ramus by the union of two or three ducts which ascend or descend respectively at right angles to the main duct. As it crosses the face, the main duct also receives from above five or six ductules from the accessory parotid gland (Fig. 29.19). As it curves round the anterior border of masseter it is often compressed and its shadow is attenuated. Deep lacerations of the cheek where the integrity of the parotid duct is in doubt should be explored and repaired using microsurgical techniques, to prevent saliva leaking into the soft tissues of the cheek and subsequent sialocele formation.

Borges AF, Alexander JE. Relaxed skin tension lines, Z-plasties on scars, and fusiform excision of lesions. Br J Plast Surg. 1962;15:242-254.

Davis RA, Anson BJ, Budinger JM, Kurth LE. Surgical anatomy of the facial nerve and parotid gland based upon a study of 350 cervicofacial halves. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1956;102:385-412.

Fromer J. The human accessory parotid gland: its incidence, nature and significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;43:671-676.

Gosain AK, Yousif NJ, Madiedo G, Larson DL, Matloub HS, Sanger JR. Surgical anatomy of the SMAS: a reinvestigation. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1993;92:1254-1263.

Kwak HH, Park HD, Youn KH, Hu KS, Koh KS, Han SH, Kim HJ. Branching patterns of the facial nerve and its communication with the auriculotemporal nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26:494-500.

Lineaweaver W, Rhoton A, Habal MB. Microsurgical anatomy of the facial nerve. Craniofac Surg. 1997;8:6-10.

Langdon JD. Parotid surgery. In: Langdon JD, Patel MF. Operative Maxillofacial Surgery. London: Chapman and Hall; 1998:381-390.

Markus AF, Delaire J, Smith WP. Facial balance in cleft lip and palate II. Cleft lip and palate and secondary deformities. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;30:296-304.

Discusses the anatomical basis for the repair of cleft lip and palate deformities..

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1976;58:80-88.

Myint K, Azian AL, Khairul FA. The clinical significance of the branching pattern of the facial nerve in Malaysian subjects. Med J Malaysia. 1992;47:114-121.

de Norman JE, McGurk M. Color Atlas and Text of the Salivary Glands. London: Mosby-Wolfe, 1995.

Park IY, Lee ME. A morphological study of the parotid gland and the peripheral part of the facial nerve in Koreans. Yonsei Med J. 1977;18:45-51.

Shimada K, Gasser RF. Morphology of the mandibulo-stylohyoid ligament in human adults. Anat Rec. 1988;222:207-210.

Wassef M. Superficial fascial and muscular layers in the face and neck: a histological study. Aesth Plast Surg. 1987;11:171-176.

Yousif NJ, Mendelson BC. Anatomy of the midface. Clin Plast Surg. 1995;22:227-240.

Ziarah HA, Atkinson ME. The surgical anatomy of the mandibular distribution of the facial nerve. Br J Oral Surg. 1981;19:159-170.