F

F wave, see Atrial flutter.

Facemasks. The traditional black antistatic rubber anaesthetic masks, with soft edges or inflatable rims, have largely been replaced by clear, disposable, plastic masks. Ideally, they should have minimal dead space and make an airtight seal with the patient’s face. Some are malleable to improve fit. Damage may be caused to eyes, nose and face if excessive pressure is used. Dead space may be measured using water, and may be up to 200 ml if the elbow attachment is included. Paediatric facemasks may be small versions of adult ones or specially designed to minimise dead space, e.g. Rendell-Baker’s (anatomically moulded to fit the face). Others are specifically designed for delivery of CPAP or non-invasive ventilation.

[Leslie Rendell-Baker (1917–2008), British-born US anaesthetist]

Facet joint injection. Injection of the posterior facets of the intervertebral joints, performed in patients with mechanical low back pain not associated with leg symptoms or signs of root irritation/compression. The posterior primary ramus of each spinal nerve divides into lateral and medial branches; the latter supplies the lower portion of the facet joint capsule at that spinal level and the upper portion of the capsule below. Thus two posterior primary rami must be blocked to anaesthetise one facet joint.

With the patient prone, the joint is located using image intensification radiography, and a needle inserted under local anaesthesia. It is walked medially and superiorly off the transverse process of the vertebra to reach the angle where the lateral edge of the facet joint meets the superomedial aspect of the transverse process. Local anaesthetic agent may be injected, or longer-lasting relief obtained by destroying the facet joint nerve using radiofrequency rhizolysis.

Facial deformities, congenital. Patients may present for radiological assessment and corrective cosmetic surgery.

• Anaesthetic considerations are usually related to:

airway difficulties, including difficult intubation.

airway difficulties, including difficult intubation.

other congenital abnormalities, e.g. CVS, renal, CNS.

other congenital abnormalities, e.g. CVS, renal, CNS.

general problems of paediatric anaesthesia and plastic surgery, e.g. fluid balance, heat and blood loss during prolonged procedures. Topical vasoconstrictors may be used to reduce bleeding.

general problems of paediatric anaesthesia and plastic surgery, e.g. fluid balance, heat and blood loss during prolonged procedures. Topical vasoconstrictors may be used to reduce bleeding.

cleft lip and palate: incidence is about 1 in 600; it may involve the lip (right, left or bilateral), palate, or combinations thereof. Other abnormalities are present in up to 15% of cases. Swallowing abnormalities may be present, with risk of aspiration pneumonitis. Surgery for cleft lip is usually performed at 3–6 months, for cleft palate at 6–12 months.

cleft lip and palate: incidence is about 1 in 600; it may involve the lip (right, left or bilateral), palate, or combinations thereof. Other abnormalities are present in up to 15% of cases. Swallowing abnormalities may be present, with risk of aspiration pneumonitis. Surgery for cleft lip is usually performed at 3–6 months, for cleft palate at 6–12 months.

Induction of anaesthesia is as for standard paediatric anaesthesia, but tracheal intubation may be difficult if the laryngoscope blade slips into the cleft. To prevent this the cleft may be packed with gauze or the Oxford blade used. Preformed or rigid tracheal tubes are usually employed, with a throat pack. Further surgery may be required in later years.

mandibular hypoplasia: e.g. in Pierre Robin syndrome (macroglossia, cleft palate and cardiac defects) and Treacher Collins syndrome (choanal atresia, downwards sloping eyes, deafness, low-set ears and cardiac defects). The small mandible leaves little room for the tongue, the larynx appearing anterior. Intubation may be extremely difficult; deep inhalational anaesthesia, awake or blind nasal intubation, cricothyrotomy and tracheostomy have been employed.

mandibular hypoplasia: e.g. in Pierre Robin syndrome (macroglossia, cleft palate and cardiac defects) and Treacher Collins syndrome (choanal atresia, downwards sloping eyes, deafness, low-set ears and cardiac defects). The small mandible leaves little room for the tongue, the larynx appearing anterior. Intubation may be extremely difficult; deep inhalational anaesthesia, awake or blind nasal intubation, cricothyrotomy and tracheostomy have been employed.

other deformities that may produce airway problems include macroglossia, cystic hygroma and branchial cyst. Raised ICP may occur with hydrocephalus and craniosynostosis (premature closure of the cranial sutures).

other deformities that may produce airway problems include macroglossia, cystic hygroma and branchial cyst. Raised ICP may occur with hydrocephalus and craniosynostosis (premature closure of the cranial sutures).

Facial nerve block. Performed to prevent blepharospasm during ophthalmic surgery, e.g. with retrobulbar block.

Facial trauma. Anaesthetic and resuscitative considerations include: possible airway obstruction and difficult tracheal intubation; risk of aspiration of gastric contents; postoperative management of the airway; and the presence of other trauma (especially to head, eyes, chest and neck).

• Classification of facial injuries:

– I: transverse fractures of mid-lower maxilla.

– II: triangular fracture from top of the nose to base of the maxilla.

zygomatic fractures: may hinder mouth opening.

zygomatic fractures: may hinder mouth opening.

– gastric contents, including swallowed blood. Fractures rarely require immediate surgery; preoperative fasting is usually possible.

– the patient should be warned about postoperative inability to open the mouth if the jaw is wired.

– rapid sequence induction may be necessary. Other techniques may be required if airway obstruction or cervical instability is present (e.g. awake fibreoptic tracheal intubation, tracheostomy).

– tracheal extubation should be performed when the patient is awake and in the lateral position. If severe oedema is anticipated, the tracheal tube is left in place postoperatively until it has subsided. Oral suction may be impossible. Dexamethasone is often given intraoperatively to reduce oedema.

– the tracheal tube may be withdrawn into the pharynx to act as a nasal airway or an airway exchange catheter placed.

[René Le Fort (1829–1893), French surgeon]

See also, Dental surgery; Maxillofacial surgery; Induction, rapid sequence; Intubation, difficult

Facilitation, post-tetanic, see Post-tetanic potentiation

Faculty of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Surgeons of England. Founded in 1948 at the request of the Association of Anaesthetists, in order to manage the academic side of anaesthesia whilst the latter body concentrated on general and political aspects. Administered and regulated the FFARCS examination and training of junior anaesthetists, until it became the College of Anaesthetists in 1988 and thence the Royal College of Anaesthetists in 1992. The corresponding Faculty in Ireland was founded in 1959, becoming a College in 1998.

Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Royal College of Anaesthetists. Established in 2010 by seven parent Colleges, its remit is to define and promote standards of education and training in critical care. Replaces the Intercollegiate Board for Training in Intensive Care Medicine. Responsible for developing a primary specialty training programme for intensive care medicine.

Faculty of Pain Medicine, Royal College of Anaesthetists. Established in 2007, to promote education, training and excellence in the delivery and management of pain medicine.

Factor VIIa, recombinant, see Eptacog alfa

Fade. Progressive reduction in strength of muscle contraction during tetanic or intermittent stimulation (e.g. train-of-four), exaggerated in non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade. Thought to be caused partly by inadequate mobilisation of acetylcholine in presynaptic nerve endings at the neuromuscular junction compared with the rate of release. Block of prejunctional acetylcholine receptors, which normally increase mobilisation by a positive feedback mechanism, is thought to be involved during neuromuscular blockade. Thus patterns of fade vary between blocking drugs, reflecting their differing affinities for prejunctional receptors (e.g. greater with tubocurarine than with pancuronium).

Failed intubation, see Intubation, failed

Fallot’s tetralogy. Commonest cause of cyanotic heart disease (65%), accounting for 5–10% of congenital heart disease.

hypoxaemia and cyanosis, usually from birth, with secondary polycythaemia. Dyspnoea occurs on effort.

hypoxaemia and cyanosis, usually from birth, with secondary polycythaemia. Dyspnoea occurs on effort.

acute exacerbations of shunt are attributed to infundibular spasm and increased pulmonary vascular resistance secondary to hypoxia. Features include worsening cyanosis, syncope and metabolic acidosis. Symptoms are relieved by squatting; thought to increase SVR and encourage pulmonary blood flow.

acute exacerbations of shunt are attributed to infundibular spasm and increased pulmonary vascular resistance secondary to hypoxia. Features include worsening cyanosis, syncope and metabolic acidosis. Symptoms are relieved by squatting; thought to increase SVR and encourage pulmonary blood flow.

supraventricular arrhythmias; right heart failure in adults.

supraventricular arrhythmias; right heart failure in adults.

a loud pulmonary murmur suggests mild stenosis. A large VSD may be unaccompanied by a murmur.

a loud pulmonary murmur suggests mild stenosis. A large VSD may be unaccompanied by a murmur.

as for congenital heart disease, VSD, cardiac surgery, paediatric anaesthesia.

as for congenital heart disease, VSD, cardiac surgery, paediatric anaesthesia.

infundibular spasm is provoked by fear and anxiety, and may be treated with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists. Sedative premedication is often given.

infundibular spasm is provoked by fear and anxiety, and may be treated with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists. Sedative premedication is often given.

avoidance of air bubbles in iv injectate, because of the risk of systemic embolisation.

avoidance of air bubbles in iv injectate, because of the risk of systemic embolisation.

peripheral vasodilatation worsens shunt and cyanosis. Vasopressor drugs (e.g. phenylephrine) may be used to increase SVR and pulmonary blood flow.

peripheral vasodilatation worsens shunt and cyanosis. Vasopressor drugs (e.g. phenylephrine) may be used to increase SVR and pulmonary blood flow.

False negative/false positive, see Errors

Familial periodic paralysis. Rare group of autosomal dominant myopathies due to defects in ion channels in skeletal muscle; characterised by episodes of severe weakness, often precipitated by extremes of temperature, physical activity, stress and large carbohydrate loads. Although traditionally classified into hypo- or hyperkalaemic variants, the condition may be associated with normal plasma potassium levels. Diagnosis may be difficult, but exercise EMG has a high level of sensitivity; detection of known gene mutations can be helpful. Treatment depends on type of disease but includes the use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g. acetazolamide), oral potassium supplements (for hypokalaemic variant) and thiazide diuretics (for hyperkalaemic variant).

Careful use of neuromuscular blocking drugs is required, with close monitoring of perioperative potassium levels. Arrhythmias may accompany potassium changes. Glucose-containing intravenous fluids should be avoided in the hyperkalaemic form of the disease. Increased susceptibility to MH is thought to be unlikely.

A needle is inserted 0.5 cm caudal to the junction of the lateral third of the inguinal ligament with the medial two-thirds. A click or ‘give’ (the latter if continuous pressure is applied to the plunger of the syringe) is felt as the needle passes through the fascia lata, followed by a second click as the fascia iliaca is pierced. An ultrasound-guided in-plane approach may also be used. 30–40 ml local anaesthetic agent (e.g. 0.25% bupivacaine) is then injected. Distal pressure is advocated to encourage cranial extension of the solution. A catheter may be inserted to allow continuous infusion of local anaesthetic.

Dalens B, Vanneuville G, Tanguy A (1989). Anesth Analg; 69: 705–13

Fascicular block, see Bundle branch block

Fasciculation. Visible contraction of skeletal muscle fibre fasciculi, seen following use of suxamethonium and other depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs. Possible damage to fibres is suggested by increased serum myoglobin and creatine kinase following suxamethonium; it may also be partly responsible for the raised potassium that occurs. May be related to post-suxamethonium myalgia, since measures to reduce the latter often reduce visible fasciculation.

Also occurs in motor neurone disease, spinal motor neurone lesions, and rarely in myopathies. Muscle fibre fibrillation (e.g. occurring after denervation injury) is invisible.

Fasciitis, necrotising, see Necrotising fasciitis

Fat embolism. Dispersion of fat droplets into the circulation, usually following major trauma. Also occurs in acute pancreatitis, burns, diabetes mellitus, joint reconstruction (possibly related to use of methylmethacrylate cement), cardiopulmonary bypass, liposuction, bone marrow harvest/bone marrow transplantation and parenteral infusion of lipids. Post-mortem evidence of fat embolism is found in 90% of fatal trauma cases. The mechanical (infloating) theory proposes that fat liberated from fractured bone enters the venous system and impacts in pulmonary capillaries, resulting in pulmonary dysfunction. Systemic embolism may occur via pulmonary arteriovenous shunts or a patent foramen ovale. The biochemical theory suggests that free fatty acids released following trauma induce an inflammatory response that causes pulmonary dysfunction, possibly mediated via an increase in plasma lipase. Both processes may occur.

confusion, restlessness, coma, convulsions, cerebral infarction.

confusion, restlessness, coma, convulsions, cerebral infarction.

dyspnoea, cough, haemoptysis. Hypoxaemia is almost inevitable. Pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary oedema may occur. Typically, gives a ‘snowstorm’ appearance on the CXR, but radiography may be normal. May contribute to development of ARDS.

dyspnoea, cough, haemoptysis. Hypoxaemia is almost inevitable. Pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary oedema may occur. Typically, gives a ‘snowstorm’ appearance on the CXR, but radiography may be normal. May contribute to development of ARDS.

petechial rash, typically affecting the trunk, pharynx, axillae and conjunctivae.

petechial rash, typically affecting the trunk, pharynx, axillae and conjunctivae.

tachycardia, hypotension, pyrexia.

tachycardia, hypotension, pyrexia.

platelets are reduced in 50%; hypocalcaemia is also common. Coagulation disorders may occur.

platelets are reduced in 50%; hypocalcaemia is also common. Coagulation disorders may occur.

fat droplets are detected in cells obtained by bronchopulmonary lavage in 70% of cases. The presence of fat droplets in the urine is a non-specific finding following trauma. Retinal examination may reveal intravascular fat globules.

fat droplets are detected in cells obtained by bronchopulmonary lavage in 70% of cases. The presence of fat droplets in the urine is a non-specific finding following trauma. Retinal examination may reveal intravascular fat globules.

O2 therapy; IPPV may be required.

O2 therapy; IPPV may be required.

supportive therapy. Fluid restriction has been advocated for reducing lung water.

supportive therapy. Fluid restriction has been advocated for reducing lung water.

corticosteroids have been shown to reduce mortality in several small studies, but optimum dosage, timing and patient selection remain unclear.

corticosteroids have been shown to reduce mortality in several small studies, but optimum dosage, timing and patient selection remain unclear.

heparin, aprotinin, aspirin, clofibrate, prostacyclin, dextran and alcohol infusion have all been tried, without conclusive benefit.

heparin, aprotinin, aspirin, clofibrate, prostacyclin, dextran and alcohol infusion have all been tried, without conclusive benefit.

Prognosis is variable and unrelated to initial severity. Mortality is 10–20%.

Fats (Lipids). Four main classes are present in plasma and cells:

– composed of glycerol and fatty acids. Formed in the GIT, liver and adipose tissue.

– endogenous triglycerides are synthesised in the liver and secreted as very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs). These are hydrolysed in the blood by lipoprotein lipase; the FFAs released are taken up by tissues for resynthesis of triglycerides or remain free in the plasma. During starvation, intracellular hormone-sensitive lipase breaks down adipose triglycerides to FFAs and glycerol (increased by β-adrenergic stimulation; decreased by insulin).

– include corticosteroids, bile salts and cholesterol (from which the former two are derived).

– plasma cholesterol is esterified with fatty acids, or circulates within low-density, high-density and intermediate-density lipoproteins (LDLs, HDLs and IDLs respectively) and VLDLs, especially the first. Unesterified cholesterol forms a major component of cell membranes.

– mainly synthesised in the liver and small intestine mucosa.

– circulate in the plasma in lipoproteins and constitute important cellular components, but not part of the depot fats. Present in myelin and cell membranes.

Lipoproteins are classified according to their size: chylomicrons 80–500 nm; VLDLs 30–80 nm; IDLs 25–40 nm; LDLs 20 nm; HDLs 7.5–10 nm. LDLs and IDLs are formed from VLDLs; HDLs are formed in the liver. High levels of cholesterol, LDLs and VLDLs are associated with ischaemic heart disease, although the role of each is controversial. HDLs may be protective.

Fazadinium bromide. Obsolete non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drug, introduced in 1972. Acts within 60 s and marketed as an alternative to suxamethonium. Withdrawn because of marked cardiovascular effects due to ganglion and vagal blockade.

Felypressin. Synthetic analogue of vasopressin, used as a locally acting vasoconstrictor. Has minimal effects on the myocardium, therefore safer than adrenaline during anaesthesia with halothane. Available in combination with prilocaine for local infiltration.

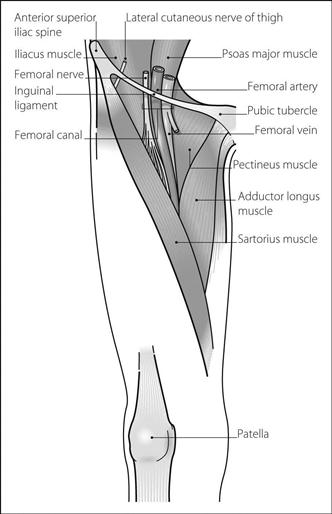

Femoral artery. Continuation of the external iliac artery; enters the thigh below the inguinal ligament midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and symphysis pubis, where it lies between the femoral vein medially and femoral nerve laterally. Descends through the femoral triangle and enters (and runs in) the subsartorial canal. Ends by piercing adductor magnus 10 cm above the knee joint where it becomes the popliteal artery.

May be cannulated for arterial BP measurement, dialysis and use of the intra-aortic counter-pulsation balloon pump as well as providing access for angiography.

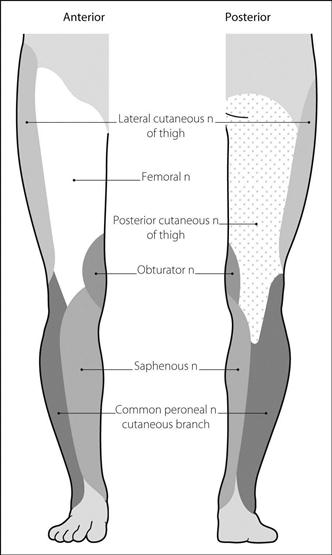

Femoral nerve block. Useful as an adjunct to general anaesthesia for operations involving the anterior thigh, hip, knee and medial lower leg. May be combined with sciatic nerve block and/or obturator nerve block for more extensive surgery to the lower limb. Also used for analgesia in leg and thigh fractures.

• Anatomy:

the femoral nerve (L2–4) arises from the lumbar plexus, passing under the inguinal ligament to enter the femoral triangle lateral to the femoral artery. Divides into terminal branches within 3–6 cm.

the femoral nerve (L2–4) arises from the lumbar plexus, passing under the inguinal ligament to enter the femoral triangle lateral to the femoral artery. Divides into terminal branches within 3–6 cm.

supplies hip and knee joints and muscles of the anterior thigh. Also supplies skin of the anterior thigh and knee, and medial lower leg and foot via the saphenous branch (Fig. 66).

supplies hip and knee joints and muscles of the anterior thigh. Also supplies skin of the anterior thigh and knee, and medial lower leg and foot via the saphenous branch (Fig. 66).

Fig. 66 Nerve supply of leg (for nerve supply of ankle and foot, see Fig. 11 Ankle, nerve blocks)

• Block:

after aspiration to exclude vascular puncture, 10–15 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. A further 5–10 ml is injected in a fan laterally as the needle is withdrawn, in case cutaneous branches arise higher than normal.

after aspiration to exclude vascular puncture, 10–15 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. A further 5–10 ml is injected in a fan laterally as the needle is withdrawn, in case cutaneous branches arise higher than normal.

injection of 30–40 ml solution at the initial site, with distal compression, has been claimed to force solution cranially to the lumbar plexus, lying between psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles (three-in-one block). In fact, a continuous femoral ‘sheath’ probably does not exist as a separate entity; the ‘three-in-one block’ is thought to represent combined femoral and lateral cutaneous nerve blocks below the inguinal ligament as a result of non-specific spread. Fascia iliaca compartment block is a more reliable and anatomically sound method of producing block of the three nerves.

injection of 30–40 ml solution at the initial site, with distal compression, has been claimed to force solution cranially to the lumbar plexus, lying between psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles (three-in-one block). In fact, a continuous femoral ‘sheath’ probably does not exist as a separate entity; the ‘three-in-one block’ is thought to represent combined femoral and lateral cutaneous nerve blocks below the inguinal ligament as a result of non-specific spread. Fascia iliaca compartment block is a more reliable and anatomically sound method of producing block of the three nerves.

Femoral triangle. Compartment of the anterior upper thigh; its borders are the inguinal ligament superomedially, the medial border of adductor longus medially and the medial border of sartorius laterally (Fig. 67). Its floor is formed by adductor longus, pectineus, psoas and iliacus muscles, and its roof by the fascia lata of the thigh. Contains the femoral artery, vein and canal within the femoral sheath; the femoral nerve and lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh lie laterally.

Femoral venous cannulation. The femoral vein is the continuation of the popliteal vein and accompanies the femoral artery in the femoral triangle, ending medial to the latter at the inguinal ligament, where it becomes the external iliac vein. Following skin cleansing, the patient’s leg is extended and slightly abducted at the hip. The femoral vein lies 1–1.5 cm medial to the femoral artery, 2–3 cm below the inguinal ligament. The needle is inserted here and advanced at an angle of 45–60° to the frontal plane. When venous blood is aspirated, the syringe is lowered to lie flat on the skin. A Seldinger technique is usually employed thereafter. Ultrasound guidance may be useful.

May be performed for central venous cannulation; traditionally avoided if other routes are available because of (probably unfounded) fears of infection or thrombosis. May be useful in superior vena caval obstruction.

Fenoldopam mesylate. Selective D1–dopamine receptor partial agonist, introduced in the USA in 1998 as an iv vasodilator drug. Also has mild α2-adrenergic agonist properties. Causes increased renal blood flow, diuresis and sodium excretion. Given as an infusion for hypertensive crisis, its short half-life of 5 min results in rapid offset of action. Metabolised in the liver to inactive compounds.

Fenoterol hydrobromide. β-Adrenergic receptor agonist, used as a bronchodilator drug. Similar in action to salbutamol and terbutaline but less β2-selective. Now only available in the UK as part of a compound aerosol formulation.

Fentanyl citrate. Synthetic opioid analgesic drug, derived from pethidine. Developed in 1960. 100 times as potent as morphine. Widely used perioperatively as an analgesic, for sedation (e.g. on ICU) and in chronic pain. Onset of action is within 1–2 min after iv injection; peak effect is within 4–5 min. Duration of action is about 20 min, terminated by redistribution initially as plasma clearance is less than for morphine. Postoperative respiratory depression is possible if large doses are used, especially in combination with opioid premedication and other depressant drugs. Causes minimal histamine release or cardiovascular changes, although may cause bradycardia.

• Dosage:

to obtund the pressor response to laryngoscopy: 7–10 µg/kg iv.

to obtund the pressor response to laryngoscopy: 7–10 µg/kg iv.

as a co-induction agent/during anaesthesia: 1–3 µg/kg iv with spontaneous ventilation; 5–10 µg/kg with IPPV. Up to 100 µg/kg is used for cardiac surgery. Muscular rigidity and hypotension are more common after high dosage. Has been used in neuroleptanaesthesia.

as a co-induction agent/during anaesthesia: 1–3 µg/kg iv with spontaneous ventilation; 5–10 µg/kg with IPPV. Up to 100 µg/kg is used for cardiac surgery. Muscular rigidity and hypotension are more common after high dosage. Has been used in neuroleptanaesthesia.

by infusion: 1–5 µg/kg/h, e.g. for sedation. For patient-controlled analgesia: 20–100 µg bolus with 3–5 min lockout.

by infusion: 1–5 µg/kg/h, e.g. for sedation. For patient-controlled analgesia: 20–100 µg bolus with 3–5 min lockout.

25, 50, 75 or 100 µg/h transdermal patch placed on the chest or upper arm and replaced (using a different site) every 72 h. A patch employing iontophoresis has been developed for postoperative patient-controlled analgesia but is not currently marketed.

25, 50, 75 or 100 µg/h transdermal patch placed on the chest or upper arm and replaced (using a different site) every 72 h. A patch employing iontophoresis has been developed for postoperative patient-controlled analgesia but is not currently marketed.

Commonly used for epidural and spinal anaesthesia (see Spinal opioids).

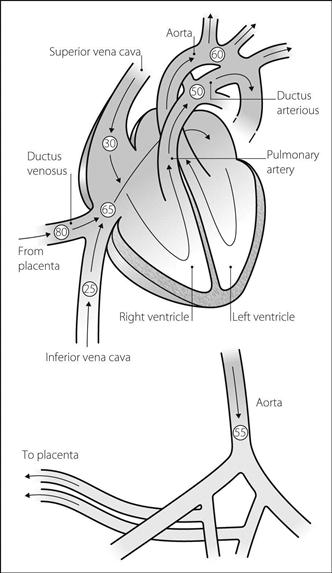

Fetal circulation. Oxygenated blood from the placenta passes through the single umbilical vein and enters the inferior vena cava, about 50% bypassing the liver via the ductus venosus. Most of it is diverted through the foramen ovale into the left atrium, passing to the brain via the carotid arteries (Fig. 68). Deoxygenated blood from the brain enters the right atrium via the superior vena cava, and passes through the tricuspid valve to the right ventricle. Because the resistance of the pulmonary vessels within the collapsed lungs is high, the blood passes from the pulmonary artery trunk through the ductus arteriosus to enter the aortic arch downstream from the origin of the carotid arteries. Thus relatively O2-rich blood is conserved for the brain, and the rest of the body is perfused with the less oxygenated blood. Deoxygenated blood reaches the placenta via the two umbilical arteries, arising from the internal iliac arteries; they receive about 60% of cardiac output.

– pH 7.2

At birth, placental blood flow ceases, and peripheral resistance increases. Lung expansion lowers pulmonary vascular resistance, both directly and via reduction of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Thus pulmonary and right heart pressures fall, and aortic and left heart pressures rise. Pulmonary blood flow increases and flow through the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale ceases. The ductus arteriosus usually closes within 48 h due to the high PO2. Pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary blood flow approach adult values by 4–6 weeks.

Neonates may revert to persistent fetal circulation, with decreased pulmonary blood flow and right-to-left shunt through the ductus arteriosus, foramen ovale, or both. This may occur if pulmonary vascular resistance is increased, e.g. by hypoxia, hypothermia, hypercapnia, acidosis or polycythaemia. It may occur during surgery if anaesthesia is too light or if the patient strains on the tracheal tube. Right-to-left shunt increases with worsening hypoxia and further reflex vasoconstriction. Ductal shunting may be demonstrated clinically by measuring O2 saturation (e.g. by pulse oximetry) in the arm and leg simultaneously; a large difference (higher saturation in the arm) represents significant ductal blood flow (i.e. pulmonary artery pressure exceeds aortic pressure). If the right ventricle fails, right atrial pressure exceeds left atrial pressure, increasing shunt through the foramen ovale.

Treatment of persistent fetal circulation includes: O2 therapy; correction of acidosis, hypercapnia and hypothermia; and inotropes and fluid administration. Drugs that lower pulmonary vascular resistance (e.g. tolazoline, isoprenaline) may be given. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation has been used.

Fetal haemoglobin. Consists of two α chains and two γ chains, the latter differing from β chains by 37 amino acids. Binds 2,3-DPG less avidly than haemoglobin A (adult), thus shifting the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve to the left (P50 is 2.4 kPa [18 mmHg]) and favouring O2 transfer from mother to fetus. At the low fetal PO2, it gives up more O2 to the tissues than adult haemoglobin would, because its dissociation curve is steeper in this part. Forms 80% of circulating haemoglobin at birth; replaced by haemoglobin A normally within 3–5 months. May persist in the haemoglobinopathies. Reactivation of production of fetal haemoglobin using hydroxyurea has been used in the treatment of sickle cell anaemia.

A variety of embryonic haemoglobins are present up to 2–3 months of gestation.

Fetal monitoring. Methods include:

heart rate, especially related to uterine contractions. May be performed intermittently using a trumpet-shaped stethoscope (Pinard) or portable ultrasound machine, or continuously using a cardiotocograph (CTG), a device that measures heart rate by external ultrasonography or fetal scalp electrode, and contractions by external transducer or intrauterine probe:

heart rate, especially related to uterine contractions. May be performed intermittently using a trumpet-shaped stethoscope (Pinard) or portable ultrasound machine, or continuously using a cardiotocograph (CTG), a device that measures heart rate by external ultrasonography or fetal scalp electrode, and contractions by external transducer or intrauterine probe:

– accelerations usually indicate reactivity and well-being.

– decelerations; usual significance:

– early (type I), i.e. with contractions: vagally mediated, due to head compression.

– late (type II), i.e. after contractions: represent hypoxia, although not always with acidosis.

– variable: usually due to cord compression; they may indicate compromise if severe.

Prolonged decelerations are more sinister, and may represent severe fetal compromise.

Recent NICE guidelines classify the CTG according to the baseline rate, variability, accelerations and decelerations as being ‘normal’ (all four criteria are normal), ‘suspicious’ (one of the four is ‘non-reassuring’) or ‘pathological’ (two or more of the four are non-reassuring or one is ‘abnormal’). Predictive value of cardiotocography is poor in low-risk patients, hence its routine use is controversial. Combination with fetal electrocardiography (ST waveform analysis) is thought to increase its sensitivity.

Signs of fetal compromise may be related to treatable conditions, e.g. uterine hypertonicity associated with excessive oxytocin administration, maternal hypotension. Aortocaval compression should always be considered, especially if regional analgesia has been provided.

Post-delivery, cord blood gas interpretation (pH represents degree of acidosis at time of delivery), Apgar scoring, time to sustained respiration and neurobehavioural testing of neonates may be assessed; these may be useful prognostically.

Fetus, effects of anaesthetic drugs on. The fetus is usually defined as such from the ninth week of gestation. Most major organ structures develop earlier than this.

• Main anaesthetic considerations:

effect of anaesthetic drugs on fetal development and spontaneous abortion:

effect of anaesthetic drugs on fetal development and spontaneous abortion:

– animal studies suggest increased fetal loss and abnormalities following prolonged exposure to high concentrations of volatile agents and N2O.

– new drugs should be avoided during early pregnancy, until more information becomes available.

effect of anaesthetic drugs given during labour on the neonate:

effect of anaesthetic drugs given during labour on the neonate:

– maternal hypoxia (e.g. due to drug-induced respiratory depression, total spinal block, convulsions).

– increased maternal catecholamine levels during inadequate general anaesthesia with awareness; uteroplacental vasoconstriction and fetal acidosis may result. Levels are reduced in labour following epidural block; this may reduce fetal acidosis.

– direct effects related to fetal plasma levels, affected by:

– placental, maternal and fetal protein concentrations and drug binding. For example, diazepam binds to albumin and is extensively transferred to the fetus; bupivacaine binds to α1-acid glycoprotein (present in lower concentrations in the fetus) and is transferred to a lesser extent.

– peak maternal plasma drug levels and their duration.

– diffusion of drug across the placenta, depending on membrane thickness, molecular size and shape, degree of ionisation and lipid solubility.

– reduced fetal hepatic and renal function. Most drugs bypass the fetal liver via the ductus venosus.

– fetal hypoxia and acidosis: cause trapping of basic drugs, e.g. opioids and local anaesthetic agents, and increase blood flow to vital centres, e.g. brain. Thus brain levels may be increased.

– fetal respiratory and CNS depression are well recognised.

– fetal opioid levels are increased by acidosis. Peak levels occur 2–5 h after im pethidine, 6 min after iv injection.

– half-life in the fetus is prolonged; e.g. pethidine: up to 20 h; that of norpethidine is longer.

– naloxone crosses the placenta easily, but its administration is usually reserved for the fetus.

– all cross the placenta rapidly, but have usually redistributed by the time of delivery. Thiopental selectively accumulates in fetal liver.

– neurobehavioural depression has been shown following their use, although the effect is small.

– inhalational anaesthetic agents:

– at low inspired concentrations, any effect is small.

– benefits of their use include uteroplacental vasodilatation and prevention of maternal awareness.

– neuromuscular blocking drugs:

– very little transfer follows normal use.

– gallamine and alcuronium cross the placenta to a slightly greater extent than the others.

– transfer varies according to dose, site of injection (e.g. high fetal levels following paracervical block), use of vasoconstrictors and different plasma protein-binding characteristics of the fetus and mother for certain drugs; e.g. umbilical vein/maternal blood levels:

– fetal methaemoglobinaemia may follow excessive doses of prilocaine.

– procaine and 2-chloroprocaine are metabolised by esterases in maternal and fetal plasma.

– others, e.g. benzodiazepines, phenothiazines:

Littleford J (2004). Can J Anesth; 51: 586–609

See also, Environmental safety of anaesthetists; Fetal monitoring; Neurobehavioural testing of neonates

FEV1, see Forced expiratory volume

FFARCS examination (Fellowship of the Faculty of Anaesthetists at the Royal College of Surgeons of England). First held in 1953; became the FCAnaes examination in 1989 following the founding of the College of Anaesthetists and the FRCA examination upon granting of a royal charter to the College in 1992. The Irish equivalent exam (FFARCSI) was first held in 1961.

rely on total internal reflection of light within bundles of glass fibres about 20 µm diameter.

rely on total internal reflection of light within bundles of glass fibres about 20 µm diameter.

may contain channels for suction, passage of gas, liquid and forceps.

may contain channels for suction, passage of gas, liquid and forceps.

tracheal intubation, with the patient awake or anaesthetised. Especially useful in cases of known difficult intubation. The endoscope may be passed through a tracheal tube, and then guided via the mouth or nose into the larynx. Lidocaine may be sprayed through a side port. The tube is passed over the ’scope into the trachea. May also be guided through various airways that act as conduits. Has been used to place endobronchial tubes.

tracheal intubation, with the patient awake or anaesthetised. Especially useful in cases of known difficult intubation. The endoscope may be passed through a tracheal tube, and then guided via the mouth or nose into the larynx. Lidocaine may be sprayed through a side port. The tube is passed over the ’scope into the trachea. May also be guided through various airways that act as conduits. Has been used to place endobronchial tubes.

checking the position of tracheal or endobronchial tubes. Also used to aid placement of percutaneous tracheostomy. May be passed through special connectors with rubber ports, thus allowing undisturbed delivery of O2 and anaesthetic gases.

checking the position of tracheal or endobronchial tubes. Also used to aid placement of percutaneous tracheostomy. May be passed through special connectors with rubber ports, thus allowing undisturbed delivery of O2 and anaesthetic gases.

assessment/diagnosis, sputum clearance and lavage, e.g. during/after thoracic surgery or in ICU.

assessment/diagnosis, sputum clearance and lavage, e.g. during/after thoracic surgery or in ICU.

Rigid laryngoscopes incorporating fibreoptic channels may also be used for tracheal intubation.

[Peter Murphy, US anaesthetist]

See also, Intubation, awake; Intubation, difficult; Intubation, endobronchial; Intubation, tracheal

Fibrin degradation products (FDPs). Products of fibrin breakdown by plasmin; thus blood levels reflect the rate of fibrinolysis (e.g. increased levels occur in DIC). Half-life is about 9 h. May inhibit clot formation by competing for fibrin polymerisation sites. Also interfere with platelet function and thrombin; thus excess fibrinolysis may impair further coagulation. May possibly damage vascular endothelium.

Measurement of FDPs (especially D-dimer) has been used to aid diagnosis of DVT, a normal value excluding thrombosis; however, levels may also be raised in many other conditions (e.g. trauma, malignancy, pregnancy, recent surgery and chronic inflammatory diseases). Thus D-dimer testing for thrombotic events has a sensitivity of about 90% and a specificity of 50%.

Fibrinogen, see Coagulation

Fibrinolysis. Dissolution of fibrin; occurs following clot formation, allowing blood vessel remodelling, and also after wound healing. Fibrinolytic and coagulation pathways are in equilibrium normally, each composed of a series of plasma precursor molecules.

Plasminogen, a globulin, is activated to form plasmin, a fibrinolytic enzyme. Activation involves clotting factors XII and XI, kallikrein and kinins, and leucocyte products. Activation of tissue plasminogen is caused by products released by endothelial cells. Plasminogen activators and plasminogen itself bind to fibrin, with plasmin formation thus localised to the site of fibrin formation. Fibrin is degraded to fibrin degradation products, with complement and platelet activation. Fibrinolysis may be decreased by stress, including surgery; effects are greatest 2–3 days postoperatively. It may be increased by fibrinolytic drugs, and following DIC as a response to the large amount of fibrin formed. Also increased by venous occlusion, catecholamines, and possibly epidural and spinal anaesthesia. Primary fibrinolysis may occur in certain malignancies.

Fibrinolytic drugs. Drugs causing fibrinolysis by activating plasminogen. Used iv and intra-arterially to prevent thrombosis, and to break up established thrombi, e.g. PE. Reduce mortality in acute MI when given iv within 12 h. Also reduce morbidity when given within 4.5 h after acute ischaemic CVA. Streptokinase acts by binding to plasminogen, the resultant complex activating other plasminogen molecules. Allergic reactions are common. Urokinase cleaves a specific peptide bond in plasminogen, converting it to plasmin; it is used mainly for thrombolysis in the eye and arteriovenous shunts. Tissue-type plasminogen activator (alteplase), reteplase and tenecteplase bind to fibrin and activate plasminogen, converting it to plasmin; like streptokinase, they are used as thrombolytics in MI. The major side effect is haemorrhage; nausea, vomiting and back pain may also occur.

Fibrocystic disease, see Cystic fibrosis

Fibronectin. Glycoprotein, involved in the removal of intravascular debris and foreign substances via interaction with circulating leucocytes, enabling the opsonisation process. May become depleted in critical illness, especially trauma and sepsis; resultant impairment of opsonisation is thought to contribute to organ hypoperfusion and MODS. Fibronectin level has been suggested as an additional indicator of disease progression in critical illness. Present in cryoprecipitate; replacement has been used therapeutically but with conflicting results.

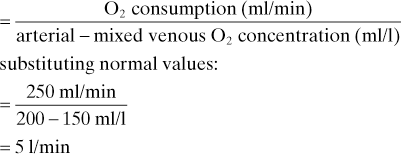

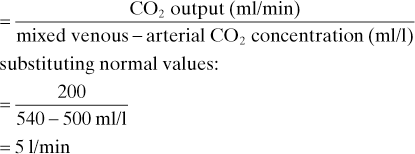

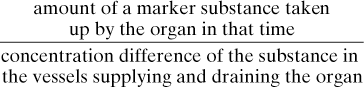

Fick principle. Blood flow to an organ in unit time =

The amount of a substance given up by an organ can also be used, e.g. CO2 (see below).

May be used to determine blood flow to individual organs, e.g. cerebral blood flow (Kety–Schmidt technique) or renal blood flow.

May also be used to determine cardiac output, using O2 or CO2 as the substance measured, and the whole body as the organ concerned:

Fick’s law of diffusion. Rate of diffusion across a membrane is proportional to the concentration gradient across that membrane.

Filgrastim, see Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

Filling ratio. Describes the extent to which cylinders containing liquefied gases (e.g. N2O and CO2) are filled; defined as the weight of substance contained in the cylinder, divided by the maximum weight of water it could contain. The presence of gas above the liquid reduces the pressure increase caused by any temperature rise, reducing the risk of pressure build-up and rupture.

Filters, breathing system. Devices routinely used for reducing contamination of anaesthetic equipment. Two main types of filter exist:

In vitro evidence suggests that pleated filters are more effective at preventing transmission of water-borne pathogens (e.g. hepatitis C); since circle systems often contain condensation their use with electrostatic filters is not recommended. Filtration efficiency varies non-linearly with particle size; most modern filters are minimally efficient at particle sizes < 0.3 µm in diameter. Testing involves challenging the filter with an aerosol of sodium chloride particles at the most penetrating particle size, using gas flow of 30 l/min for adult filters (15 l/min for paediatric). Modern filters usually incorporate a heat-moisture exchanger.

Filtration fraction. Ratio of GFR to renal plasma flow (RPF). As RPF falls, GFR remains fairly constant because of efferent arteriolar constriction, causing filtration fraction to rise. Normally 0.16–0.2.

Fink effect. Reduced alveolar concentration of a gas resulting from its dilution by another gas leaving the bloodstream and entering the alveoli. Analogous but opposite to the second gas effect. Originally described (as ‘diffusion anoxia’) in 1955 as the underlying cause of hypoxaemia seen at the end of anaesthesia, when N2O leaving the bloodstream dilutes alveolar O2. Since recognised as having little clinical importance, the effect of hypoventilation and  mismatch being much more important.

mismatch being much more important.

First-pass metabolism. Metabolism of a substance once absorbed, occurring before it reaches the systemic circulation. Active metabolites may be formed. Most commonly refers to metabolism by the liver following oral administration of drugs, e.g. propranolol, morphine, lidocaine and GTN (i.e. drugs with a high extraction ratio). Drugs may be given by alternative routes to bypass the liver, e.g. parenterally, sublingually or rectally. May also occur in the intestinal mucosa following oral administration (e.g. methyldopa, chlorpromazine, midazolam), and in the bronchial mucosa following inhalation (e.g. isoprenaline).

Flail chest. Disruption of chest wall integrity, where a portion of the thoracic cage becomes detached from the bony structure of the rest. The flail segment no longer moves outwards on inspiration, but is free to be drawn inwards by negative intrathoracic pressure; it is pushed out during expiration whilst the rest of the thorax contracts. Occurs in severe chest trauma with multiple fractures involving several ribs. May also result from surgery.

hypoventilation, with reduced tidal volume and vital capacity. Pendelluft is now thought not to occur; mediastinal shift results in air entry to both lungs, although overall hypoventilation may be severe. Hypoventilation is further exacerbated by pain. Ability to cough is reduced due to mechanical impairment and pain.

hypoventilation, with reduced tidal volume and vital capacity. Pendelluft is now thought not to occur; mediastinal shift results in air entry to both lungs, although overall hypoventilation may be severe. Hypoventilation is further exacerbated by pain. Ability to cough is reduced due to mechanical impairment and pain.

underlying lung contusion/atelectasis/pneumothorax with resultant shunt and

underlying lung contusion/atelectasis/pneumothorax with resultant shunt and  mismatch; thought to be more important than hypoventilation.

mismatch; thought to be more important than hypoventilation.

associated injuries, e.g. to mediastinum, head, abdomen.

associated injuries, e.g. to mediastinum, head, abdomen.

mediastinal shift may affect cardiac output.

mediastinal shift may affect cardiac output.

• Management is as for chest trauma, i.e.:

analgesia (e.g. systemic opioids/intercostal nerve block/epidural analgesia).

analgesia (e.g. systemic opioids/intercostal nerve block/epidural analgesia).

treatment of hypovolaemia and associated injuries.

treatment of hypovolaemia and associated injuries.

chest drainage if required.

chest drainage if required.

nasogastric drainage helps prevent gastric dilatation.

nasogastric drainage helps prevent gastric dilatation.

if arterial blood gases are acceptable, no further treatment may be required. Improved oxygenation and chest wall splinting may be achieved by CPAP.

if arterial blood gases are acceptable, no further treatment may be required. Improved oxygenation and chest wall splinting may be achieved by CPAP.

tracheal intubation and IPPV. May be continued until the underlying lung improves or surgical fixation of the flail segment (i.e. up to several weeks). IMV has been used.

tracheal intubation and IPPV. May be continued until the underlying lung improves or surgical fixation of the flail segment (i.e. up to several weeks). IMV has been used.

early fixation of rib fractures is preferred by some surgeons.

early fixation of rib fractures is preferred by some surgeons.

Pettiford BL, Luketich JD, Landreneau RJ (2007). Thorac Surg Clin; 17: 25–33

Flame ionisation detector. Device used in analysis of gas mixtures, separated, e.g. by gas chromatography. A potential difference is applied across a flame of hydrogen gas burning in air. Addition of organic vapour to the gas stream causes a change in current flow across the flame, the amount of change proportional to the amount of substance present. Used only to quantify the amount of a known substance, not to identify unknown ones.

Ranges for explosive mixtures occur within these limits, especially with high O2 concentration. The stoichiometric mixture lies within the explosive range. Flammability is greater in N2O than in O2, because the former decomposes to produce O2 with release of energy. Addition of water vapour reduces flammability.

Modern, non-flammable agents will ignite only at higher concentrations than occur during anaesthesia, and require much greater amounts of energy to initiate ignition (activation energy).

Flecainide acetate. Class Ic antiarrhythmic drug. Slows impulse conduction by blocking sodium channels, thus prolonging phase 0 of the cardiac action potential (in both the conducting system and myocardial cells). Used for severe VT and extra-systoles, and SVT, especially those involving accessory pathways (e.g. Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome).

• Dosage:

2 mg/kg up to 150 mg, over 10–30 min iv (with ECG monitoring).

2 mg/kg up to 150 mg, over 10–30 min iv (with ECG monitoring).

by infusion: 1.5 mg/kg/h for 1 h; 0.1–0.25 mg/kg/h thereafter.

by infusion: 1.5 mg/kg/h for 1 h; 0.1–0.25 mg/kg/h thereafter.

100 mg orally bd for VT (50 mg for SVT).

100 mg orally bd for VT (50 mg for SVT).

dizziness, visual disturbances, corneal deposits.

dizziness, visual disturbances, corneal deposits.

myocardial depression (minor), proarrhythmias.

myocardial depression (minor), proarrhythmias.

resistance to endocardial pacing.

resistance to endocardial pacing.

increased plasma levels in hepatic/renal failure (levels should be monitored).

increased plasma levels in hepatic/renal failure (levels should be monitored).

has been associated with increased risk of cardiac arrest after MI, therefore reserved for life-threatening arrhythmias.

has been associated with increased risk of cardiac arrest after MI, therefore reserved for life-threatening arrhythmias.

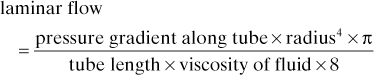

Flow. Volume of fluid moving per unit time. Flow through a tube may be:

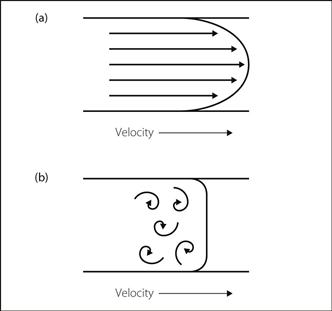

laminar: flow is smooth and without eddies. Flow velocity reduces towards the tube’s sides (approaching zero at the edge); flow at the centre is greatest, at approximately twice the mean (Fig. 69a). Described by:

laminar: flow is smooth and without eddies. Flow velocity reduces towards the tube’s sides (approaching zero at the edge); flow at the centre is greatest, at approximately twice the mean (Fig. 69a). Described by:

turbulent (Fig. 69b): caused when the tube is unevenly shaped, or when the fluid flows through an orifice or around sharp edges. Also occurs from laminar flow when flow velocity is high, exceeding the critical velocity. Reynolds’ number describes the relationship between tube and fluid characteristics and velocity at which turbulent flow occurs. Turbulent flow is proportional to:

turbulent (Fig. 69b): caused when the tube is unevenly shaped, or when the fluid flows through an orifice or around sharp edges. Also occurs from laminar flow when flow velocity is high, exceeding the critical velocity. Reynolds’ number describes the relationship between tube and fluid characteristics and velocity at which turbulent flow occurs. Turbulent flow is proportional to:

– radius2.

–  .

.

Flow-directed balloon-tipped pulmonary artery catheters, see Pulmonary artery catheterisation

Flow generators, see Ventilators

Flowmeters. Devices for measuring flow, usually referring to gas flow, e.g. from cylinders and anaesthetic machines, or in breathing systems.

• May be:

– water depression flowmeter. The pressure is measured with a simple water manometer.

– pneumotachograph. Pressure is measured electronically using transducers.

– rotameter, simple ball flowmeter and dry bobbin flowmeter. The size of the orifice is determined by the height of the bobbin in its tube: the greater the height, the larger the orifice. In the rotameter and ball flowmeter, the tube is of tapered bore, being wider at the top than at the bottom. The dry bobbin flowmeter tube is of uniform diameter, with small holes arranged longitudinally. The variability of the effective orifice size is provided by the number of holes below the bobbin, i.e. the bobbin’s height.

thermistor flowmeter: the cooling effect of a gas stream on a thermistor varies with flow rate.

thermistor flowmeter: the cooling effect of a gas stream on a thermistor varies with flow rate.

ultrasonic flowmeter: turbulent eddies are formed around a rod in the gas path. The frequency of oscillation of the eddies, measured by Doppler probe, is proportional to flow rate. Alternatively, ultrasound beams may be projected diagonally across the gas, and transit time measured.

ultrasonic flowmeter: turbulent eddies are formed around a rod in the gas path. The frequency of oscillation of the eddies, measured by Doppler probe, is proportional to flow rate. Alternatively, ultrasound beams may be projected diagonally across the gas, and transit time measured.

Flow can also be determined by measuring the volume of gas per unit time, e.g. using a respirometer.

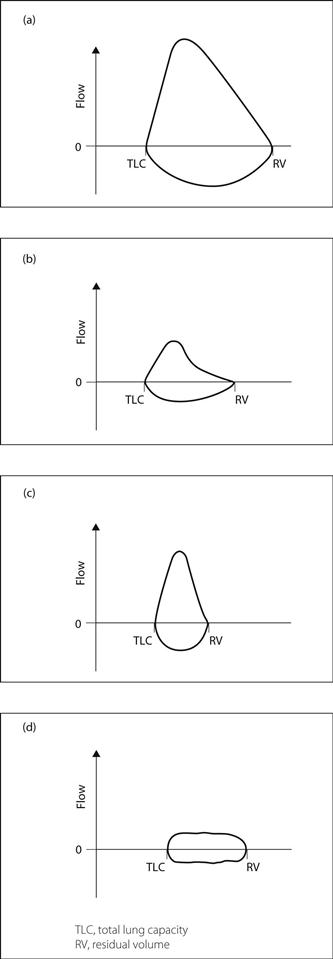

Flow–volume loops. Curves resulting from simultaneous measurement and plotting of air flow and lung volume during a maximal forced expiration. If residual volume is known, lung volume may be determined by measuring expired volume. Characteristic loops are obtained in certain conditions, although the loops obtained in practice are rarely as easily distinguishable (Fig. 70). Also useful for assessing the efficacy of bronchodilator therapy in COPD.

Flucloxacillin. Penicillinase-resistant penicillin used to treat staphylococcal infections. Peak levels occur within an hour of administration. 90% protein-bound; although metabolised in the liver, 50% appears unchanged in the urine.

• Dosage:

• Side effects: as for benzylpenicillin. Acute cholestatic jaundice may occur even after stopping therapy.

Fluconazole. Triazole antifungal drug used to treat local and systemic candidiasis and cryptococcal infection (including meningitis), especially associated with HIV infection. Well absorbed orally, with peak levels within 6 h. Elimination half-life 30 h.

• Dosage: 50–400 mg orally/iv daily.

• Side effects: nausea, vomiting, rashes, allergic reactions, toxic epidermal necrolysis, hepatic impairment. May increase blood levels of the antihistamines terfenadine and astemizole, resulting in prolonged Q–T syndrome and fatal ventricular arrhythmias, including torsade de pointes.

Flucytosine. Intravenous antifungal drug used in systemic yeast infections; often used together with amphotericin, with which it is synergistic. Resistance may occur.

Fludrocortisone acetate. Mineralocorticoid used for replacement therapy in adrenocortical insufficiency, congenital adrenal hyperplasia and postural hypotension associated with autonomic neuropathy. Has similar actions to aldosterone; also has mild hydrocortisone-like actions.

Fluid. Form of matter that continuously deforms when subjected to a shearing force, i.e. gas or liquid. Continuous shearing force results in flow; resistance to flow is proportional to viscosity. For a Newtonian fluid (e.g. water) viscosity is constant for different shear rates and flows; for a non-Newtonian fluid (e.g. blood), it varies with shear rates and flows.

Fluid balance. Normal approximate daily fluid intake of a 70-kg adult:

250 ml from metabolism within the body.

Loss in sweat is normally negligible but may exceed several litres in hot environments. Insensible losses are also increased in high temperatures. About 5% of body water is exchanged per day in adults, 15% in infants; hence the increased risk of dehydration in the latter.

Balance is normally regulated to maintain ECF volume and osmolality; changes are detected by baroreceptors and osmoreceptors, with resultant compensatory mechanisms:

water intake is regulated by thirst; increased by hypovolaemia and hyperosmolality.

water intake is regulated by thirst; increased by hypovolaemia and hyperosmolality.

cardiovascular compensation for hypovolaemia.

cardiovascular compensation for hypovolaemia.

urinary output is regulated by vasopressin, atrial natriuretic peptide and the renin/angiotensin system.

urinary output is regulated by vasopressin, atrial natriuretic peptide and the renin/angiotensin system.

• Fluid balance may be disturbed in patients presenting for anaesthesia, perioperatively and in ICU:

reduced intake, e.g. coma, dysphagia, nausea, fasting instructions.

reduced intake, e.g. coma, dysphagia, nausea, fasting instructions.

increased intake, e.g. excessive iv administration.

increased intake, e.g. excessive iv administration.

redistribution, e.g. to third space.

redistribution, e.g. to third space.

reduced output, e.g. syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

reduced output, e.g. syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

increased output, e.g. sweating, polyuria, vomiting, diarrhoea.

increased output, e.g. sweating, polyuria, vomiting, diarrhoea.

Administration of iv fluids perioperatively is now routine, though; excessive dextrose administration may lead to hyperglycaemia and hyponatraemia, whilst excessive salt solution administration may cause peripheral and pulmonary oedema. Improved recovery with reduced PONV has been claimed following fluid administration (especially containing dextrose) during minor surgery compared with no fluids.

• IV fluid administration should be guided by the following:

maintenance requirements: 40 ml/kg/day (1.6 ml/kg/h). Requirements are greater in paediatric anaesthesia.

maintenance requirements: 40 ml/kg/day (1.6 ml/kg/h). Requirements are greater in paediatric anaesthesia.

Careful attention to fluid balance is required in all perioperative and critically ill patients to prevent complications, e.g. hypernatraemia, hyponatraemia, dehydration, renal failure. Therapy is guided by CVP, urine output, BP, pulse and electrolyte balance. Body weight is a useful supplement to fluid intake/output charts.

Fluid therapy, see Intravenous fluids

Fluidics. Technology of operating control systems by utilising flow characteristics of gases or liquids. Has been used in control mechanisms of ventilators, e.g. employing the Coanda effect. The direction of a jet of gas in a valve may be switched by ‘signal’ jets of driving gas across the main jet. Combinations of signal jets allow complex manipulation of the valve output, without moving parts.

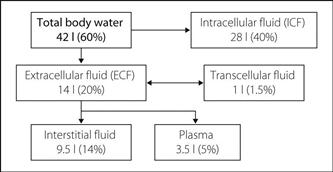

Fluids, body. Approximately 60% of male body weight is water; 50–55% in females (greater proportion of fat). Total body water may be measured using a dilution technique with deuterium oxide (heavy water). Its main constituent compartments are intracellular fluid (ICF), ECF, plasma and interstitial fluid (Fig. 71). Approximately 1 litre is contained within the GIT and CSF (transcellular fluid).

In neonates, ECF exceeds 30% (but plasma is still 5%), and ICF is less than 40%. These differences are greatest in premature babies, when ECF exceeds ICF. During childhood, the adult situation slowly develops.

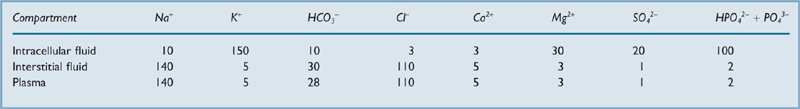

Composition of fluid compartments is shown in Table 20.

Movement of substances is also affected by other substances, e.g. Donnan effect.

Water moves across membranes from solutions of low concentrations to those of high concentrations (osmosis). Depending on their constitution, different iv fluids will fill certain compartments more than others.

Flumazenil. Benzodiazepine antagonist, structurally related to midazolam and introduced in 1987. A competitive inhibitor of benzodiazepines at the central GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor complex. Used to reverse excessive sedation due to benzodiazepines, e.g. following attempted suicide, prolonged sedation with benzodiazepines in ICU and iatrogenic overdose. Benzodiazepine metabolism is unaffected. 50% protein-bound.

• Side effects: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, confusion, pulmonary oedema. Has caused excessive excitement and convulsions, especially in patients maintained on long-term benzodiazepines, e.g. for epilepsy. Because of its short half-life (less than 1 h), its effects may wear off with recurrence of sedation.

Fluoride ions. Nephrotoxic ions implicated in the high-output renal failure seen following methoxyflurane administration. Evidence for their role:

degree of renal impairment is proportional to plasma concentration:

degree of renal impairment is proportional to plasma concentration:

– subclinical evidence of renal impairment occurs above 50 µmol/l.

infusion of fluoride ions into rats produces similar renal effects.

infusion of fluoride ions into rats produces similar renal effects.

Mechanism of renal damage is unclear but may involve impairment of both renal Na/K/ATPase systems and vasopressin action.

• Levels are highest after methoxyflurane, but may be raised after other halogenated volatile agents:

methoxyflurane: 50–60 µmol/l after 2.5 MAC hours; 90–120 µmol/l after 5 MAC hours.

methoxyflurane: 50–60 µmol/l after 2.5 MAC hours; 90–120 µmol/l after 5 MAC hours.

enflurane: up to 30 µmol/l after prolonged use (over 9 h). Plasma levels are highest in obese patients. Enzyme induction with isoniazid is thought to increase levels.

enflurane: up to 30 µmol/l after prolonged use (over 9 h). Plasma levels are highest in obese patients. Enzyme induction with isoniazid is thought to increase levels.

isoflurane: under 5 µmol/l even after prolonged surgery. Levels of up to 90 µmol/l have been reported after several days’ use for sedation in ICU.

isoflurane: under 5 µmol/l even after prolonged surgery. Levels of up to 90 µmol/l have been reported after several days’ use for sedation in ICU.

halothane: minimal production of fluoride ions.

halothane: minimal production of fluoride ions.

sevoflurane: up to 40 µmol/l after prolonged surgery (unaffected by obesity).

sevoflurane: up to 40 µmol/l after prolonged surgery (unaffected by obesity).

desflurane: minimal production of fluoride ions.

desflurane: minimal production of fluoride ions.

Fluotec vaporiser, see Vaporisers

Flupirtine maleate. Non-opioid, non-NSAID centrally acting analgesic drug, recently investigated. Thought to block NMDA receptors, although the precise mechanism of action is unclear. Also causes muscular relaxation via enhancement of GABA-mediated spinal inhibition. Not available in the UK.

Flurbiprofen. NSAID available for oral and pr administration; has been used for postoperative analgesia.

Fluroxene (Trifluoroethyl vinyl ether). Obsolete inhalational anaesthetic agent, introduced in 1954. The first fluorine-containing volatile agent. Explosive, possibly mutagenic, and toxic to experimental animals due to biotransformation to trifluoroethanol.

Flying squad, obstetric. Mobile team including anaesthetist, obstetrician and midwife; first suggested in 1929, and organised in Glasgow in 1933. The usual problems of obstetric anaesthesia and neonatal resuscitation are compounded by the unfamiliar environment, limitation of facilities, requirement for portable equipment and lack of patient preparation. Commonest emergency is postpartum haemorrhage caused by retained placenta. Use of a flying squad has declined as the number of home deliveries has decreased. The above problems have led many units to withdraw anaesthetic cover from such squads, with emphasis on rapid transfer of the patient to hospital.

See also, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, neonatal; Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia

Foetal, see Fetal

Fondaparinux sodium. Synthetic factor Xa inhibitor; sulphated pentasaccharide derived from the factor Xa-binding moiety of unfractionated heparin. Licensed for treatment of acute coronary syndromes and prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in adults.

• Dosage:

treatment of unstable angina/non-S-T segment elevation MI and DVT prophylaxis in immobilised patients: 2.5 mg sc od (in surgical patients, first dose 6 h after skin closure).

treatment of unstable angina/non-S-T segment elevation MI and DVT prophylaxis in immobilised patients: 2.5 mg sc od (in surgical patients, first dose 6 h after skin closure).

treatment of DVT and PE: 5, 7.5 or 10 mg sc od (for body weight < 50 kg, 50–100 kg and > 100 kg respectively) until oral anticoagulation established.

treatment of DVT and PE: 5, 7.5 or 10 mg sc od (for body weight < 50 kg, 50–100 kg and > 100 kg respectively) until oral anticoagulation established.

treatment of S-T segment elevation MI: 2.5 mg iv, followed by 2.5 mg sc od.

treatment of S-T segment elevation MI: 2.5 mg iv, followed by 2.5 mg sc od.

• Side effects: haemorrhage, purpura, thrombocytopenia, GI upset, rash.

Fondation Européenne d’Enseignement en Anaesthésiologie (Foundation for European Education in Anaesthesiology; FEEA). Organisation founded in 1986 (with financial support from the European Union) to provide continuous medical education in anaesthesiology throughout Europe. Acts in agreement with national anaesthetic societies and organises courses throughout Europe and, more recently, South America.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). US organisation, involved in testing new drugs and reviewing test results. Also controls imports, and regulates foods and cosmetics. Companies must apply to the FDA before initiating clinical trials. Evolved after World War II from the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act, restricting labelling and advertising of drugs; amended in 1968 to require that drugs be shown to be efficacious as well as safe. Thus enforces laws enacted by US Congress. Previously, the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 and subsequent amendments attempted to prevent improper labelling and fraudulent claims by manufacturers.

Foot, nerve blocks, see Ankle, nerve blocks; Digital nerve block

Force. That which changes a body’s shape or state of motion. Derived SI unit of force is the newton; in base units this is equivalent to m⋅kg/s2.

Forced diuresis. Method of increasing renal excretion of certain drugs using iv fluids or diuretics to increase urinary volume. Sometimes used in poisoning and overdoses. Further drug removal is achieved by manipulating urinary pH, thereby ‘trapping’ the ionised fraction of the drug and preventing its diffusion back into the bloodstream, since charged molecules diffuse poorly across biological membranes.

used in poisoning with acid drugs, e.g. salicylates and barbiturates.

used in poisoning with acid drugs, e.g. salicylates and barbiturates.

500 ml/h of the following fluids are administered in rotation:

500 ml/h of the following fluids are administered in rotation:

– 500 ml 1.26% sodium bicarbonate.

used in poisoning with alkaline drugs, e.g. amfetamines, phencyclidines.

used in poisoning with alkaline drugs, e.g. amfetamines, phencyclidines.

1000 ml/h of the following fluids are administered in rotation:

1000 ml/h of the following fluids are administered in rotation:

Severe metabolic upset and circulatory overload may occur. The technique is rarely used now, since it has been superseded by haemodialysis and haemofiltration.

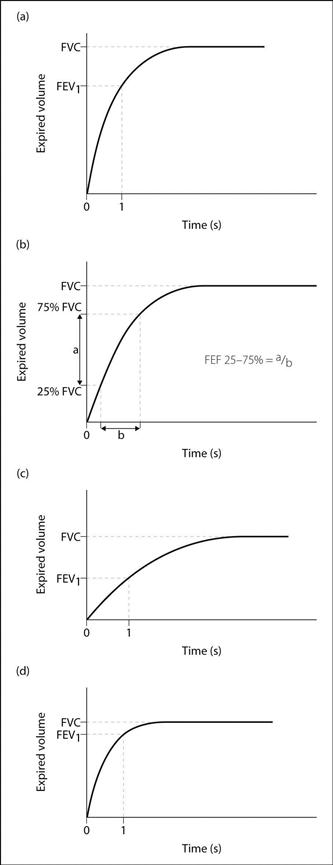

Forced expiration. Means of investigating lung function, from which may be measured: forced expiratory flow rate (FEF25–75%), FEV, FVC and peak expiratory flow rate. Other suggested measurements exclude the first 200 ml of expiration, or analyse the flow rate at 50% of vital capacity.

Flow–volume loops and data from spirometers (e.g. the Vitalograph) may be analysed (Fig. 72). Repetition following bronchodilator therapy may indicate the extent of reversible airway obstruction.

Forced expiratory flow rate (FEF25–75%). Average flow rate measured at between 25% and 75% of forced maximal expired volume (Fig. 72). Usually changes with forced expiratory volume, but has wider spread of normal values.

See also, Forced expiration; Lung function tests; Peak expiratory flow rate

Forced expiratory volume (FEV). Volume of gas forcibly exhaled from full inspiration, in a set period of time (normally 1 s; the volume is then called FEV1). Normally 80% of FVC, which may be measured at the same time using a spirometer. Reduced in obstructive lung disease, as is the FEV1/FVC ratio. In restrictive disease, FEV1 may be normal, but FVC is reduced.

Easier and more comfortable to measure than maximal voluntary ventilation.

Forced vital capacity (FVC). Vital capacity measured when expiration is forced. Closure of some airways may occur when intrathoracic pressure is high, causing air-trapping. FVC thus may be less than ‘true’ vital capacity. Reduced in restrictive disease, the supine position, the elderly, muscle weakness, abdominal swelling, pain, and when premature airway closing occurs during forced expiration, e.g. emphysema.

See also, Forced expiration; Lung function tests; Lung volumes

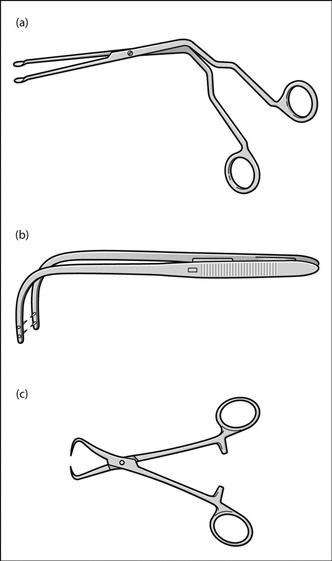

Forceps. Many varieties may be used by anaesthetists, e.g. (Fig. 73):

Magill’s forceps: introduced in 1920 to assist placement of gum-elastic bougies for insufflation anaesthesia. Used to guide tracheal tubes into the larynx, or nasogastric tubes into the oesophagus, under direct vision. May damage the tracheal tube cuff if grasped. Also used to place pharyngeal packs or to remove foreign bodies. The operator’s hand is held out of the line of vision by the angled handles. Adult and paediatric sizes are available, as are single-use versions. Many modifications have been described.

Magill’s forceps: introduced in 1920 to assist placement of gum-elastic bougies for insufflation anaesthesia. Used to guide tracheal tubes into the larynx, or nasogastric tubes into the oesophagus, under direct vision. May damage the tracheal tube cuff if grasped. Also used to place pharyngeal packs or to remove foreign bodies. The operator’s hand is held out of the line of vision by the angled handles. Adult and paediatric sizes are available, as are single-use versions. Many modifications have been described.

[Herman Krause (1848–1921), German laryngologist; Berkley GA Moynihan (1865–1936), English surgeon]

Foreign body, inhaled. Leading cause of accidental death in children less than 4 years old. May obstruct upper or lower airways. Should be considered in any child with stridor or persistent cough and chest infections. Diagnosis is based on history, clinical findings and imaging (although only 11% of aspirated objects are radio-opaque). Most small objects lodge in the right main bronchus, because of its more vertical angle of origin and greater width. Organic matter (e.g. peanuts) may cause intense bronchial inflammatory reactions within a few hours, with oedema and possibly bronchial obstruction. Bronchiectasis may be a late complication. Other features may include:

features of airway obstruction.

features of airway obstruction.

• Removal is via bronchoscopy (rigid most commonly). Anaesthetic management:

– premedication with atropine. Anxiolytic drugs may be helpful.

– an experienced anaesthetist’s presence is mandatory, as is good communication with the surgeon.

– classic technique is inhalational induction of anaesthesia; sevoflurane is usually the modern drug of choice (replacing halothane). N2O is avoided in case of distal air-trapping, and to raise FIO2. Induction may be slow.

– lidocaine spray to the vocal cords may reduce risk of perioperative laryngospasm.

– intraoperatively, both spontaneous and controlled ventilation can be used, although IPPV is often avoided because of the risk of blowing the object distally. Adequate depth of anaesthesia and oxygenation may be difficult to maintain with an inhalational agent and spontaneous ventilation, without excessive hypercapnia. TIVA (e.g. with remifentanil and propofol) may provide more reliable and constant depth of anaesthesia, and can be titrated to allow spontaneous ventilation.

– close monitoring is required in case of bronchospasm or laryngospasm.

Fidowski CD, Zheng H, Firth PG (2010). Anesth Analg; 111: 1016–25

Forward failure, see Cardiac failure

Foscarnet sodium. Antiviral drug, reserved for treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS (when ganciclovir is contraindicated) or for herpes simplex virus infections that are unresponsive to aciclovir.

Fosphenytoin sodium. Water-soluble prodrug, completely converted to phenytoin after parenteral administration, with a conversion half-life of 15 min. Useful in treating acute partial and generalised tonic–clonic seizures. Particularly appropriate in management of status epilepticus. 1.5 mg of fosphenytoin is equivalent to 1 mg of phenytoin. Can be administered iv or im with good absorption. Following its administration, monitoring of phenytoin levels is not recommended until conversion to phenytoin is complete (i.e. within 2 h after iv infusion and 4 h after im injection).

Fospropofol. Water-soluble phosphorylated prodrug of propofol; converted to the latter by plasma alkaline phosphatases within a few minutes of iv injection. Licensed in the USA for sedation in adults during endoscopic procedures (but not for general anaesthesia). Presented as a clear, colourless solution of 3.5% concentration. Initial iv bolus dose is 6.5 mg/kg followed by supplemental doses of 1.6 mg/kg titrated to effect. Onset of action and recovery are slower than with propofol. Does not cause pain on injection but frequently (> 50% incidence) causes unpleasant perineal paraesthesia (e.g. burning, stinging) and pruritus. Other adverse effects (e.g. hypotension, respiratory depression) are as for propofol.

Fourier analysis. Mathematical breakdown of waveforms into simple sine wave constituents. Any complex waveform consists of sine waves of different frequencies: the slowest (fundamental) frequency and harmonics thereof. Used in analysis and reconstruction of waveforms, e.g. transmission of electrical signals. The higher the frequencies analysed, the more accurate the reproduction.

[Baron Jean-Baptiste Fourier (1768–1830), French mathematician]

Fournier’s gangrene, see Necrotising fasciitis

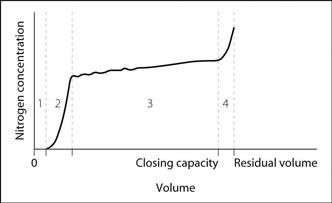

Fowler’s method (Single-breath nitrogen washout). Method of investigation of lung volumes, described in 1948. The subject breathes air normally, and takes a maximal breath of O2 (i.e. to vital capacity) from the end of normal expiration (i.e. FRC). Exhaled nitrogen concentration is measured during maximal slow expiration (i.e. to residual volume), and plotted against volume of expired gas. A rapid-response nitrogen meter is required.

• Four phases are described (Fig. 74):

phase 1: O2 from the conducting airways (anatomical dead space), containing no nitrogen.

phase 1: O2 from the conducting airways (anatomical dead space), containing no nitrogen.

phase 2: mixture of dead-space gas and alveolar gas.

phase 2: mixture of dead-space gas and alveolar gas.

phase 4: at closing capacity, lower alveoli and airways collapse, thus the exhaled gas comes from upper airways only. At the onset of the O2 inspiration, the upper airways were already considerably expanded (with nitrogen-containing air) compared with lower ones, since most ventilation is of upper lung regions at normal tidal volume. Most of the inspired O2 therefore entered the lower alveoli, since they started off smaller. When they collapse, nitrogen-rich gas from the upper alveoli is exhaled, giving rise to phase 4.

phase 4: at closing capacity, lower alveoli and airways collapse, thus the exhaled gas comes from upper airways only. At the onset of the O2 inspiration, the upper airways were already considerably expanded (with nitrogen-containing air) compared with lower ones, since most ventilation is of upper lung regions at normal tidal volume. Most of the inspired O2 therefore entered the lower alveoli, since they started off smaller. When they collapse, nitrogen-rich gas from the upper alveoli is exhaled, giving rise to phase 4.

Anatomical dead space is measured to the mid-point of phase 2.

CO2 measurement may be used in a similar way, using capnography.

Fractional shortening, see Left ventricular fractional shortening

Frankenhauser’s plexus block, see Paracervical block

FRCA examination (Fellowship of the Royal College of Anaesthetists). Predated by the FFARCS examination (1953–89) and the FCAnaes examination (1989–92). Since 1985 (as the FFARCS examination) it consisted of three parts: I, relating to the fundamentals of clinical anaesthesia; II, relating to the basic sciences; III, relating to the practice of anaesthesia as a whole. Replaced in 1996 by a two-part examination: the Primary, relating to basic sciences and clinical safety; and the Final, relating to applied basic sciences and the practice of anaesthesia/intensive care. Recent pass rates are in the order of 40–50% for each part.

Involved in normal phagocyte function and host defence; released into phagosomes to destroy bacteria. May also be produced by radiation and certain chemicals, and increased production has been implicated in many disease processes, e.g. pulmonary O2 toxicity, halothane hepatitis, ARDS, paracetamol poisoning, burns, carcinogenesis and bowel ischaemia. Defence mechanisms against normal free radical formation may be overwhelmed, resulting in oxidation of tissue components. Reactions with free radicals may liberate further free radicals.

Free water clearance, see Clearance, free water

Freud, Sigmund (1856–1939). Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, the inventor of psychoanalysis. Postulated that cocaine might be a treatment for morphine addiction, and a stimulant for psychoneurotic patients. Investigated the drug with his friend Koller, who introduced it as the first local anaesthetic drug. Fled from Vienna to London in 1938 to escape the Nazis.

upper motor neurone weakness, with upgoing plantar reflexes (if present).

upper motor neurone weakness, with upgoing plantar reflexes (if present).

ataxia, dysarthria and nystagmus.

ataxia, dysarthria and nystagmus.

impaired joint position, vibration and touch sense. Reflexes may be absent.

impaired joint position, vibration and touch sense. Reflexes may be absent.