Chapter 55 Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis

A heterogeneous disease, EAA has varying clinical presentations associated with the inhalation of antigens, leading primarily to a diffuse mononuclear cell inflammation of the small airways and lung parenchyma. Classifying etiologic antigens into three broad categories is clinically helpful: microbial agents, animal proteins, and low-molecular-weight chemicals (Table 55-1). Most particulate antigens are of respirable size, less than 3 to 5 µm in diameter, and deposit in the alveoli. However, some antigens are deposited in airways and then become soluble, as occurs with Alternaria spores.

Table 55-1 Three Major Categories of Antigens Causing Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis (EAA)

| Antigen | Exposure | Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Agents | ||

| Bacteria | ||

| Thermophilic | Organic dust | Farmer’s lung, bagassosis, mushroom worker’s lung |

| Nonthermophilic | Water, hot tubs | Humidifier lung, hot tub lung |

| Fungi | ||

| Aspergillus spp. | Moldy hay and moldy water | Farmer’s lung, ventilation pneumonitis |

| Animal bedding | Doghouse disease | |

| Esparto grass | Espartosis | |

| Trichosporon cutaneum (T. biegelii) | Damp wood and mats | Japanese summer-type EAA |

| Alternaria spp. | Wood pulp | Wood pulp worker’s lung |

| Cryptostroma corticale | Wood bark | Maple bark stripper’s lung |

| Animal and Plant Proteins | ||

| Animal proteins | ||

| Avian proteins | Bird droppings, feathers (bloom) | Bird fancier’s lung, pigeon breeder’s lung |

| Urine, serum, pelts | Rats, gerbils | Animal handler’s lung |

| Plants | ||

| Coffee | Coffee bean dust | Coffee worker’s lung |

| Low Molecular Weight Chemicals | ||

| Toluene diisocyanate (TDI) | Paints, resins, polyurethane foams | Isocyanate (TDI) EAA |

| Drugs | Amiodarone, gold, procarbazine | Drug-induced EAA |

| Methylmethacrylate | Dental laboratories | |

Clinical Features

Several diagnostic criteria have been proposed to differentiate EAA from other interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). A prospective multicenter cohort study of patients who had a pulmonary syndrome with EAA in the differential diagnosis adopted a “clinical prediction rule” for the diagnosis of active EAA (Table 55-2). Significant predictors in the final model included exposure to a known offending antigen, positive precipitating antibodies, recurrent episodes of symptoms, inspiratory crackles, symptoms 4 to 8 hours after exposure, and weight loss. These criteria are helpful when combined with BAL and high-resolution CT in determining the likelihood of EAA.

Table 55-2 Clinical Prediction Rule for Diagnosis of Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Exposure to known antigen | 38.8 (11.6-129.6) |

| Positive precipitating antibodies | 5.3 (2.7-10.4) |

| Recurrent episodes of symptoms | 3.3 (1.5-7.5) |

| Inspiratory crackles | 4.5 (1.8-11.7) |

| Symptoms 4-8 hours after exposure | 7.2 (1.8-28.6) |

| Weight loss | 2.0 (1.0-3.9) |

From Lacasse Y et al: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168:952-958, 2003.

Imaging

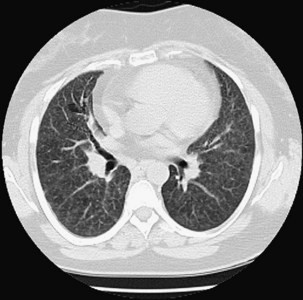

The chest radiograph is often normal in patients with EAA, with an estimated sensitivity of only 10%. In acute EAA, radiographs may show diffuse ground-glass or air space consolidation. Patients with subacute EAA may have a combination of nodular or reticulonodular opacities with ground-glass attenuation. Chronic fibrotic EAA usually has the appearance of reticular opacities with honeycombing on chest radiographs (Figure 55-1).

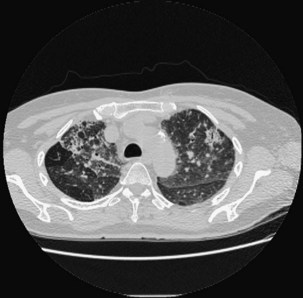

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest is the most sensitive imaging study for the detection of subtle changes associated with EAA (Figures 55-2 and 55-3). Multiple HRCT abnormalities are seen in patients with EAA that are loosely correlated with histologic and pulmonary function abnormalities (Table 55-3). Up to 50% of patients will have mediastinal lymphadenopathy; the nodes are usually smaller than 20 mm and are not detectable on the chest radiograph.

Table 55-3 Radiologic Abnormalities in EAA with Physiologic/Histologic Association

| HRCT Abnormality | Physiologic Correlate | Histologic Correlate |

|---|---|---|

| Centrilobular nodules | None | Cellular bronchiolitis, alveolitis |

| Ground-glass opacities | Restriction, decreased diffusion capacity | Alveolitis, fine fibrosis, granulomas in alveolar septa |

| Mosaic attenuation | Obstruction | Bronchiolitis |

| Emphysema | Obstruction, decreased diffusion capacity | Emphysema, bronchiolar inflammation |

| Reticulation, honeycomb | Restriction, decreased diffusion capacity | Fibrotic change Traction bronchiectasis |

EAA, extrinsic allergic alveolitis; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography.

Other Diagnostic Testing

Histopathology

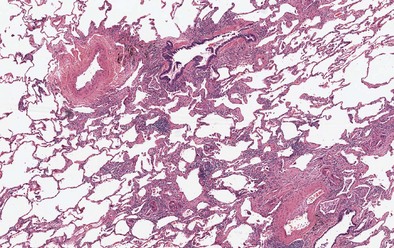

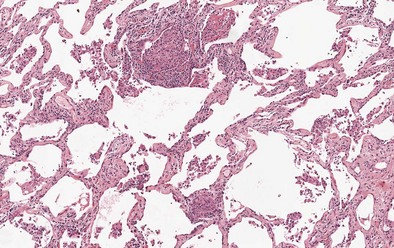

Findings on transbronchial biopsy are nonspecific and nondiagnostic in 50% of patients with EAA. Proceeding to surgical lung biopsy may be necessary when faced with diagnostic uncertainty, because features of EAA overlap with many other inflammatory lung diseases. The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of disease, although lung biopsies are rarely required in patients with acute EAA. Findings in acute EAA include neutrophilic and eosinophilic alveolar infiltration, small-vessel vasculitis, diffuse alveolar damage, and vascular immunoglobulin and complement deposition. A classic triad of histopathologic features is found in subacute EAA: lymphocytic alveolitis; small, loose non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas; and cellular bronchiolitis (Figures 55-4 and 55-5). Foamy macrophages are present in air spaces, while lymphocytes are more prominent in the interstitium. Additionally, foci of obliterative bronchiolitis, intraalveolar fibrosis, and cellular NSIP may be found in subacute EAA.

Camarena A, Aquino-Galvez A, Falfan-Valencia R, et al. PSMB8 (LMP7) but not PSMB9 (LMP2) gene polymorphisms are associated with pigeon breeder’s hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Respir Med. 2010;104:889–894.

Camarena A, Juarez A, Mejia M, et al. Major histocompatibility complex and tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms in pigeon breeder’s disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1528–1533.

Dakhama A, Hegele RG, Laflamme G, et al. Common respiratory viruses in lower airways of patients with acute hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1316–1322.

Lacasse Y, Assayag E, Cormier Y. Myths and controversies in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:631–642.

Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Clinical diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:952–958.

Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Classification of hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a hypothesis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149:161–166.

Lynch DA, Rose CS, Way D, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: sensitivity of high-resolution CT in a population-based study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:469–472.

Rose CS, Lara AR Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, Mason RJ, et al. Murray and Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier, 2010.

Selman M. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a multifaceted deceiving disorder. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:531–547.

Selman M. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In: Schwarz M, King TEJ. Interstitial lung disease. Shelton, Conn: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011:597–635.