CHAPTER 17 Externalizing Conditions

Externalizing problems in children represent the most common reasons for referral for behavioral intervention.1 However, these behaviors undergo many changes in form and frequency during childhood and adolescence, and without an understanding of normal developmental trends, it may be difficult to determine whether a given child’s behavior is typical or problematic. Therefore, clinicians must have background knowledge in the normal development of externalizing behaviors. We begin this chapter by describing how compliant/noncompliant behaviors, anger, and aggression change in expression and frequency through childhood and adolescence. In subsequent sections, we explore how externalizing behavior manifests in problematic forms, how various biopsychosocial factors contribute to the development of children’s problems with aggression and conduct, and how aggression and conduct problems can be assessed. We conclude by discussing how these problems can be effectively treated with psychosocial methods.

NORMAL VARIATIONS IN EXTERNALIZING BEHAVIORS AND RELATED EMOTIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

Compliance Behaviors

Although most people involved in the care of children have an idea of what is meant by compliance and noncompliance, these behaviors often prove difficult to define operationally. In their treatment manual for noncompliant children, McMahon and Forehand2 used the definition “appropriate following of an instruction within a reasonable and/or designated time” to operationalize compliance, noting that it is important to distinguish between the initiation of compliance and the completion of the specified task.3 Five to 15 seconds was suggested as a reasonable period for the initiation of compliance. McMahon and Forehand2 defined noncompliance as “the refusal to initiate or complete a request” and/or “failure to follow a previously stated rule that is currently in effect” (p 2). In defining compliance and noncompliance, clinicians must also recognize that these are not stand-alone behaviors but are interactional processes between adult and child. Parenting behaviors can affect a child’s likelihood of compliance, and child characteristics and responses can, in turn, affect parenting behaviors.

Children first begin to understand the consequences of their own behavior between 6 and 9 months of age and may also learn to recognize the word “no” during this time. Increasing physical development, cognitive abilities, social skills, and receptive language skills lead to improved abilities to respond to verbal directions, and children are generally able to follow simple instructions by age 2 years. Nonetheless, noncompliance with commands is very common for 2- and 3-year-old children, possibly because of parental expectations of resistance (i.e., “the terrible twos”) and parents’ resulting failure to train their young children to comply.4

Compliance levels are expected to increase with age in typically developing children.5 However, the collection of normative data has proved to be complex and elusive because of sample characteristics and measurement issues.2,4 A number of investigators have found the expected progression of compliant behaviors in young children as they age. Vaughn and colleagues6 reported increases in compliance with maternal requests between 18 and 30 months of age, and Kochanska and associates7 reported an upward trend in one form of compliance from 14 to 33 months of age. Brumfield and Roberts4 reported that whereas 2- and 3-year-old children complied with only 32.2% of maternal commands, the compliance rate for 4- and 5-year-olds reached 77.7%. However, Kuczynski and Kochanska8 reported no change in compliance to maternal requests between toddler age (1½ to 3½ years) and age 5 years. Kuczynski and Kochanska8 did find that direct defiance and passive noncompliance decreased with age, although simple refusal and negotiation (an indirect form of noncompliance) increased. Another longitudinal study reported stable rates of noncompliance from ages 2 to 4 years.9

By the time they reach school age, children are expected to comply with adult requests the majority of the time. In a review of studies, McMahon and Forehand2 suggested that compliance rates are approximately 80% for normally developing children. Patterson and Forgatch,10 however, reported lower compliance rates in a sample of “non-problem 10- and 11-year-old boys”: 57% in response to maternal requests and 47% in response to paternal requests.

In adolescence, noncompliant behaviors often increase above childhood levels in typically developing youths. Developmental changes in cognition and social skills, combined with adolescents’ growing independence and need to establish their own identity, may lead to increased parent-adolescent conflict. However, developmental research suggests that typical levels of parent-adolescent conflict are manageable and do not constitute the period of severe “storm and stress” described in early models of family relations.11,12 Conflict tends to be at its most extreme during early adolescence and to decline from early adolescence to mid-adolescence and from mid-adolescence to late adolescence.13

Boys and girls differ in their normative rates of oppositional, noncompliant behaviors; boys demonstrate higher rates than do girls during childhood. However, the gender difference closes with age, and boys and girls demonstrate increasingly similar rates as they progress through adolescence.14

Anger and Aggression

Like compliance and noncompliance, angry and aggressive behaviors are common to all children, representing clinically significant problems only when frequent and severe enough to disrupt a child’s or family’s daily life. Anger is often, but not always, a precursor to aggression in children. In fact, the presence or absence of anger is often a defining factor in the classification of aggression. Anger is a key feature of hostile aggression, which carries the intent to harm and is accompanied by emotional arousal, but not of instrumental aggression, which is motivated by external reward rather than by emotional arousal. Similarly, reactive aggression is emotionally driven and takes the form of angry outbursts, whereas proactive aggression is instrumentally driven and takes the form of goal-driven behaviors (e.g., domination of others or obtaining a desired object).15

Another classification of aggression differentiates between physical aggression and relational aggression. Girls may be more likely to engage in acts of relational aggression, which cause harm by damaging relationships or threatening to do so (e.g., spreading rumors, social exclusion).16

Not surprisingly, children who are identified as angry by parents and teachers are more likely to display externalizing behaviors.17–19 Relations have also been reported between anger in children and internalizing problems20 and between anger in children and being victimized by peers.21

Anger and Development

Anger is one of the earliest emotions to appear in infancy. Between ages 2 and 6 months, infants engage in recognizable displays of anger, including a characteristic cry, and by 7 months, facial expressions of anger can be reliably detected.22 Caregivers tend to respond to infants’ anger expressions by ignoring them or reacting negatively, thus beginning the socialization process against anger.23,24 As children learn what is socially acceptable, their displays of anger may diminish. For example, one study demonstrated that by 24 months of age, toddlers are able to modulate their expression of anger and are more likely to display sadness, which is more likely to elicit a supportive response from a caregiver.25

Anger is likely to be accompanied by physically aggressive behavior in very young children, but with increasing age and developmental level, expressions of anger change in typically developing children. Dunn,26 for example, found that physical aggression and teasing were equally prevalent in 14-month-old children, but by age 24 months, children were much more likely to tease. During early childhood, children are expected to learn appropriate ways to manage and express their anger. Young children demonstrate progressive increases in their vocabulary of emotional terms and increased understanding of the causes and consequences of emotions.27,28 By the time they reach elementary school age, children have generally developed a sophisticated understanding of the types of emotional displays that are appropriate and functional in a given context.29 Shipman and colleagues29 reported that children in the first through fifth grades identified verbalization of feelings as the most appropriate means of expression of anger, followed by facial displays. The children identified sulking, crying, and aggression as equally inappropriate ways of expressing anger. These findings are consistent with those of other research demonstrating that, with age, children become increasingly less likely to engage in expressive displays of anger as they come to recognize that their ability to maintain emotional control is important to their social functioning.30

Aggression and Development

An understanding of normal developmental trends in aggressive behavior is an important starting point in identifying clinically significant problems for children of a given age. In typically developing children, aggressive behaviors follow a declining trend with age during childhood and adolescence. Large-scale longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that rates of aggression decline during childhood and adolescence; aggressive behavior occurs at the highest levels in the youngest children and at the lowest levels in late adolescence.14,31–33

Declining trajectories of aggression over time hold for children of both genders; however, at any given point in childhood, boys tend to display higher rates of aggressive behavior than do girls. In fact, boys may display twice as much aggression as girls do during childhood. These gender differences appear to be present very early on, before 4 years of age, and therefore are unlikely to be caused by socialization effects associated with school attendance. Aggressive behavior declines more quickly for boys, and by late adolescence, the rates of aggression in boys and girls are indistinguishable.14,31 Aggressive acts are nearly nonexistent in typically developing late adolescent–aged youths of both genders.

Aggressive Behavioral Problems

Because of a number of factors that are further elaborated upon later in this chapter, some children display externalizing behaviors that exceed the normal amounts or typical variations. Within this group of disruptive children, aggression is a frequent and particularly concerning complaint. Aggression is one of the most stable problem behaviors in childhood, with a developmental trajectory toward negative outcomes in adolescence, such as drug and alcohol use, truancy and dropout, delinquency, and violence.34 Additional studies indicate that children’s aggressive behavior patterns may escalate to include a wide range of severe antisocial behaviors in adolescence.35 The negative trajectory may even continue into adulthood, as demonstrated by Olweus’s finding that of adolescents identified as bullies, 60% had their first criminal conviction by age 24.36

These findings highlight the fact that aggressive behavior can have serious and negative implications for a child’s future. The negative effects are not, however, limited to the aggressive individual, inasmuch as aggressive behavior, by definition, has the potential to cause harm or injury to others. In today’s schools, aggressive bullying, which may be verbal, physical, or psychological, is increasingly recognized as a serious problem.37 Bullying is a deliberate act with the intent of harming the victims.38 Examples of direct bullying include hitting and kicking, charging interest on goods and stealing, name calling and intimidation, and sexual harassment. Other forms of bullying that are more indirect in nature (i.e., relational bullying) include spreading rumors about peers and gossiping.39 The victims of bullies usually tend to be shy and likely to seek help.40

Children who display high levels of aggressive behavior often exhibit additional externalizing behaviors and may meet criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder diagnosis such as Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) or Conduct Disorder.41 Although not an explicit part of the diagnosis, aggression may accompany the characteristic pattern of negativistic, hostile, and defiant behavior associated with a diagnosis of ODD. More severe disruptive behaviors, including aggression toward people or animals, destruction of property, theft, and deceit, are associated with conduct disorder. Prevalence rates for these diagnoses are estimated to be from 2% to 16% of the general population for ODD and from 1 to more than 10% for conduct disorder.41 ODD is mostly closely associated with “aggressive/oppositional behaviors” under the category of “negative/antisocial behaviors” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Primary Care: Child and Adolescent Version.41a The features of conduct disorder are similar to “secretive antisocial behaviors” under the same category. Some researchers are beginning to identify psychological features that are linked to subsequent psychopathy.42 Youths who have psychopathic features display manipulation, impulsivity, and remorseless patterns of interpersonal behavior, are usually referred to as “callous” or “unemotional,” and are considered to be conceptually different from youths with a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder.43,44

Symptoms associated with ODD are age inappropriate, usually appearing before 8 years of age and no later than adolescence.41 These symptoms include angry, defiant, irritable, and oppositional behaviors and are usually first manifested in the home environment. The diagnosis of ODD should be made only if these behaviors occur more frequently than what would be typically expected of same-aged peers with a similar developmental level. Conduct disorder symptoms such as setting fires, breaking and entering, and running away from home are more severe and may become evident as early as the preschool years, but these behaviors usually begin in middle childhood to middle adolescence. Less severe symptoms (e.g., lying, shoplifting, and physical fighting) are observed initially, followed by intermediate behaviors such as burglary; the most severe behaviors (e.g., rape, theft while confronting a victim) usually emerge last.41 Professionals who provide services to children and adolescents must be aware of the symptoms of ODD and provide intervention, because ODD is a common antecedent to conduct disorder. Furthermore, a significant subset of individuals who receive a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder, particularly those with an early onset, subsequently develop antisocial personality disorder.41 Table 17-1 lists diagnostic criteria for ODD and Conduct Disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR).41

TABLE 17-1 DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | Conduct Disorder |

|---|---|

| A pattern of negativistic, hostile, and defiant behavior lasting at least 6 months, during which four (or more) of the following occur: | A repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of three (or more) of the following criteria in the past 12 months, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months: |

DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorder, 4th edition, text revision.

With regard to gender features, ODD is more prevalent in boys than in girls before puberty, but the rates are fairly equal after puberty. ODD symptoms are typically similar in boys and girls, except that boys exhibit more confrontational behavior and have more persistent symptoms.41 Diagnoses of Conduct Disorder, particularly the childhood-onset type, are more common in boys than in girls. According to the American Psychiatric Association,41 boys with conduct disorder usually display symptoms such as “fighting, stealing, vandalism, and school discipline problems,” and girls with conduct disorder usually engage in “lying, truancy, running away, substance use, and prostitution.”

Childhood disorders rarely occur in isolation, and comorbidity issues are important to consider in treating children within clinical populations.45 ODD and conduct disorder are often observed in conjunction with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), academic underachievement and learning disabilities, and internalizing disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety disorders). Among youth with conduct disorder and ODD, 50% also have a diagnosis of ADHD.45 Furthermore, the hyperactive-impulsive subtype of ADHD is more closely associated with aggression than is the inattentive subtype. ODD in conjunction with ADHD increases the likelihood for the development of early-onset conduct disorder symptoms.46,47 Children with disruptive behaviors are at a greater risk for dropping out of school and thus becoming part of a deviant peer group in their neighborhood. Moreover, children with both conduct problems and depressive symptoms are more likely to engage in substance abuse as adolescents than are children with conduct problems alone.

With regard to differential diagnoses, ODD should not be diagnosed if the symptoms occur exclusively during a mood or psychotic disorder. As previously noted, ADHD often co-occurs with ODD, warranting two separate diagnoses. Furthermore, the oppositional behavior associated with ODD and the impulsive and disruptive behaviors associated with ADHD should be distinguished when a diagnosis is made.41 The diagnosis of ODD should not be made if the individual meets criteria for diagnosis of an adjustment disorder, conduct disorder, or, if the individual is aged 18 years or older, antisocial personality disorder. Last, the behaviors associated with ODD must be more frequent and severe than what is typically expected and lead to significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning.41 As with ODD, a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder should not be made if the behaviors occur exclusively during the course of a psychotic disorder, mood disorder, or ADHD. Furthermore, Conduct Disorder should not be diagnosed when the individual meets criteria for an adjustment disorder or, if the individual is 18 years of age or older, antisocial personality disorder. According to the DSM-IV-TR, when an individual meets criteria for both ODD and Conduct Disorder, a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder should be made.

ETIOLOGY: RISK AND CAUSAL FACTORS WITHIN A CONTEXTUAL SOCIAL-COGNITIVE MODEL

The contextual social-cognitive model,48 which is derived from etiological research on childhood aggression, indicates that certain family and community background factors (neighborhood problems, maternal depression, poor social support, marital conflict, low socioeconomic status) have both a direct effect on children’s externalizing behavior problems and an indirect effect through their influence on key mediational processes (parenting practices, children’s social cognition and emotional regulation, children’s peer relations). A child’s developmental course is set within the child’s social ecology, and an ecological framework is required.49 Risk factors that are biologically related are noted first, followed by contextual factors in the model, and, finally, by their effect on children’s developing social-cognitive and emotional regulation processes.

Biological and Temperament Factors

With regard to biological and temperamental child factors, some prenatal factors such as maternal exposure to alcohol, methadone, cocaine, and cigarette smoke and severe nutritional deficiencies50–53 have been found to have direct effects on childhood aggression. However, aggression is more commonly the result of interactions between the child’s risk factors and environmental factors, in diathesis-stress models.54 Thus, risk factors such as birth complications, genes, cortisol reactivity, testosterone, abnormal serotonin levels, and temperament all contribute to children’s conduct problems but only when environmental factors such as harsh parenting or low socioeconomic status are present.55–59

Examples of these diathesis-stress models abound in the literature on children’s risk factors. Birth complications such as preeclampsia, umbilical cord prolapse, forceps delivery, and fetal hypoxia increase the risk of later violence among children but only when the infants subsequently experience adverse family environments or maternal rejection.55,58 Higher levels of testosterone among adolescents and higher cortisol reactivity to provocations are associated with more violent behavior but only when the children or adolescents live in families in which they experience high levels of abuse by parents or low socioeconomic status.57,60 Children who have a gene that expresses only low levels of monoamine oxidase A have a higher rate of adolescent violent behavior but only when they have experienced high levels of maltreatment by parents.61 Similar patterns of findings are found when children’s temperament characteristics are examined as child-level risk factors. Highly active children,62 children with high levels of emotional reactivity,63 and infants with difficult temperament56 are at risk for later aggressive and conduct problem behavior but only when they have parents who provide poor monitoring or harsh discipline. The children’s family context can serve as a key moderator of children’s underlying propensity for an antisocial outcome.

Contextual Family Factors

A wide array of factors in the family, ranging from poverty to more general stress and discord, can affect childhood aggression and conduct problems. Children’s aggression has been linked to family background factors such as parent criminality, substance use, and depression64–66; low socioeconomic status and poverty67; stressful life events64,68; single and teenage parenthood69; marital conflict70; and insecure, disorganized attachment.71 All of these family factors are intercorrelated, especially with socioeconomic status,72 and low socioeconomic status assessed as early as the preschool years has been predictive of teacher- and peer-rated behavior problems at school.73 These broad family risk factors can influence child behavior through their effect on parenting processes.

Starting as early as the preschool years, marital conflict probably causes disruptions in parenting that contribute to children’s high levels of stress and consequent aggression.74 Both boys and girls from homes in which marital conflict is high are especially vulnerable to externalizing problems such as aggression and conduct disorder; this is found even after age and family socioeconomic status are controlled.74

Parenting Practices

Parenting processes linked to children’s aggression75,76 include (1) nonresponsive parenting at age 1, in which pacing and consistency of parent responses do not meet children’s needs; (2) coercive, escalating cycles of harsh parental interactions and child’s noncompliance, starting in the toddler years, especially for children with difficult temperaments; (3) harsh, inconsistent discipline; (4) unclear directions and commands; (5) lack of warmth and involvement; and (6) lack of parental supervision and monitoring as children approach adolescence.

Parental physical aggression, such as spanking and more punitive discipline styles, has been associated with oppositional and aggressive behavior in both boys and girls. Poor parental warmth and involvement contribute to parents’ use of physically aggressive punishment practices. Weiss and colleagues77 found that parent ratings of the severity of parental discipline were positively correlated with teachers’ ratings of aggression and behavior problems. In addition to higher aggression ratings, children experiencing harsh discipline practices exhibited poorer social information processing; this was found even when the possible effects of socioeconomic status, marital discord, and child temperament were controlled. Of importance is that although such parenting factors are associated with childhood aggression, child temperament and behavior also affect parenting behavior.78

Poor parental supervision has also been associated with childhood aggression. Haapasalo and Tremblay79 found that boys who fought more often with their peers reported having less supervision and more punishment than did boys who did not fight. Interestingly, the boys who fought reported having more rules than the boys who did not fight, which suggests the possibility that parents of aggressive boys may have numerous strict rules that are difficult to follow.

Contextual Peer Factors

Children with disruptive behaviors are at risk for being rejected by their peers.80 Childhood aggressive behavior and peer rejection are independently predictive of delinquency and conduct problems in adolescence.81,82 Aggressive children who are also socially rejected tend to exhibit more severe behavior problems than do children who are either only aggressive or only rejected. As with bidirectional relations evident between the degree of parental positive involvement with their children and children’s aggressive behavior over time,83 children’s aggressive behavior and their rejection by their peers affect each other reciprocally.84 Children who have overestimated perceptions of their actual social acceptance can be at particular risk for aggressive behavior problems in some settings.85

Despite the compelling nature of these findings, race and gender may moderate the relation between peer rejection and negative adolescent outcomes. For example, Lochman and Wayland81 found that peer rejection ratings of African American children in a mixed-race classroom were not predictive of subsequent externalizing problems in adolescence, whereas peer rejection ratings of white children were associated with future disruptive behaviors. Similarly, whereas peer rejection can be predictive of serious delinquency in boys, it can fail to be so with girls.86

As children with conduct problems enter adolescence, they tend to associate with deviant peers. We believe that many of these teenagers are continually rejected from more prosocial peer groups because they lack appropriate social skills and, as a result, they turn to antisocial cliques as their only sources of social support.86 The tendency for aggressive children to associate with one another increases the probability that their aggressive behaviors will be maintained or will escalate, because of modeling effects and reinforcement of deviant behaviors.87 The relation between childhood conduct problems and adolescent delinquency is at least partially mediated by deviant peer group affiliation.88

Contextual Community and School Factors

Neighborhood and school environments have also been found to be risk factors for aggression and delinquency beyond the variance accounted for by family characteristics.89 Exposure to neighborhood violence increases children’s aggressive behaviors,90,91 reinforces their acceptance of aggression,91 and begins to have heightened effects on the development of antisocial behavior during the middle childhood, preadolescent years.92 Neighborhood problems disrupt parents’ ability to supervise their children adequately93 and have a direct effect on children’s aggressive, antisocial behaviors94,95 beyond the effects of poor parenting practices. Early onset of aggression and violence has been associated with neighborhood disorganization and poverty, partly because children who live in lower socioeconomic status and disorganized neighborhoods are not well supervised, engage in more risk-taking behaviors, and experience the deviant social influences that are apparent in problematic crime-ridden neighborhoods.

Schools can further exacerbate children’s conduct problems through frustration with academic demands caused, in part, by their children’s learning problems and by peer influences. The density of aggressive children in classroom settings can increase the amount of aggressive behavior exhibited by individual students.96,97

Social Information Processing

Children begin to form stable patterns of processing social information and of regulating their emotions on the basis of (1) their temperament and biological dispositions and (2) their contextual experiences with family, peers, and community.98 Children’s emotional reactions, such as anger, can contribute to later substance use and other antisocial behavior, especially when children have not developed good inhibitory control.99 The contextual social-cognitive model48 stresses the reciprocal, interactive relationships among children’s initial cognitive appraisal of problem situations, their efforts to think about solutions to the perceived problems, their physiological arousal, and their behavioral response. The level of physiological arousal depends on the individual’s biological predisposition to become aroused and varies according to the interpretation of the event.100 The level of arousal further influences the social problem solving, operating either to intensify the fight-or-flight response or to interfere with the generation of solutions. Because of the ongoing and reciprocal nature of interactions, children may have difficulty extricating themselves from aggressive behavior patterns.

Aggressive children have cognitive distortions at the appraisal phases of social-cognitive processing because of difficulties in encoding incoming social information and in accurately interpreting social events and others’ intentions. They also have cognitive deficiencies at the problem solution phases of social-cognitive processing, as evidenced by their generating maladaptive solutions for perceived problems and having nonnormative expectations for the usefulness of aggressive and nonaggressive solutions to their social problems. In the appraisal phases of information processing, aggressive children recall fewer relevant cues about events,101 base interpretations of events on fewer cues,102 selectively attend to hostile rather than neutral cues,103 and recall the most recent cues in a sequence, with selective inattention to earlier presented cues.104 At the interpretation stage of appraisal processing, aggressive children have a hostile attributional bias: They tend to infer excessively that others are acting toward them in a provocative and hostile manner.101,102 These attributional biases tend to be more prominent in reactively aggressive children than in proactively aggressive children.105

The problem solving stages of information processing begin with the child accessing the goal that the individual chooses to pursue, thereby affecting the responses generated for resolving the conflict in the next processing stage. Aggressive children have social goals that are more dominance and revenge oriented, and less affiliation oriented, than those of nonaggressive children.106 In the fourth information- processing stage, potential solutions for coping with a perceived problem are recalled from memory. At this stage, aggressive children demonstrate deficiencies in both the quality and the quantity of their problem-solving solutions. These differences are most pronounced in the quality of offered solutions: Aggressive children offer fewer verbal assertion solutions,107,108 fewer compromise solutions,101 more direct action solutions,108 a greater number of help-seeking or adult intervention responses,109 and more physically aggressive responses110 to hypothetical vignettes describing interpersonal conflicts. The nature of the social problem-solving deficits for aggressive children varies, depending on their diagnostic classification. Boys with Conduct Disorder diagnoses produce more aggressive/antisocial solutions in vignettes about conflicts with parents and teachers and fewer verbal/nonaggressive solutions in peer conflicts than do boys with ODD.111 Thus, children with conduct disorder have broader problem-solving deficits in multiple interpersonal contexts than do children with ODD.

The fifth processing step involves two components: (1) identifying the consequences for each of the solutions generated and (2) evaluating each solution and consequence in terms of the individual’s desired outcome. In general, aggressive children evaluate aggressive behavior as more positive112 than do children without aggressive behavior difficulties. Children’s beliefs about the utility of aggression and about their ability to successfully enact an aggressive response can increase the likelihood of displayed aggression, because children with these beliefs are more likely to also believe that this type of behavior will help them achieve the desired goals, which then influences response evaluation.101 Deficient beliefs at this stage of information processing are especially characteristic of children with proactive aggressive behavior patterns105 and for youths who have callous-unemotional traits consistent with early phases of psychopathy.113 Researchers have demonstrated that these beliefs about the acceptability of aggressive behavior lead to deviant processing of social cues, which in turn leads to children’s aggressive behavior114; this indicates that these information-processing steps have recursive effects rather than strictly linear effects on each other.

The final information-processing stage involves behavioral enactment, or displaying the response that was chosen in the preceding steps. Aggressive children are less adept at enacting positive or prosocial interpersonal behaviors.102 This interpretation suggests that improving the ability to enact positive behaviors may influence aggressive children’s beliefs about their ability to engage in these more prosocial behaviors and thus change the response evaluation.

Schemas within the Social-Cognitive Model

Schemas have been proposed to have a significant effect on the information-processing steps within the contextual social-cognitive model underlying cognitive-behavioral interventions with aggressive children.115,116 Schemas can involve children’s expectations and beliefs of others115 and of themselves, including their self-esteem and narcissism.117 Early in the information-processing sequence, when the individual is perceiving and interpreting new social cues, schemas can have a clear, direct effect by narrowing the child’s attention to certain aspects of the social cue array.118 A child who believes it essential to be in control of others and who expects that others will try to dominate him or her, often in aversive ways, will attend particularly to verbal and nonverbal signals about someone else’s control efforts, easily missing accompanying signs of friendliness or attempts to negotiate. Schemas can also have indirect effects on information processing through their influence on children’s expectations for their own behavior and for others’ behavior in specific situations. Lochman and Dodge119 found that aggressive boys’ perceptions of their own aggressive behavior was affected primarily by their prior expectations, whereas nonaggressive boys relied more on their actual behavior to form their perceptions.

ASSESSMENT OF EXTERNALIZING BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

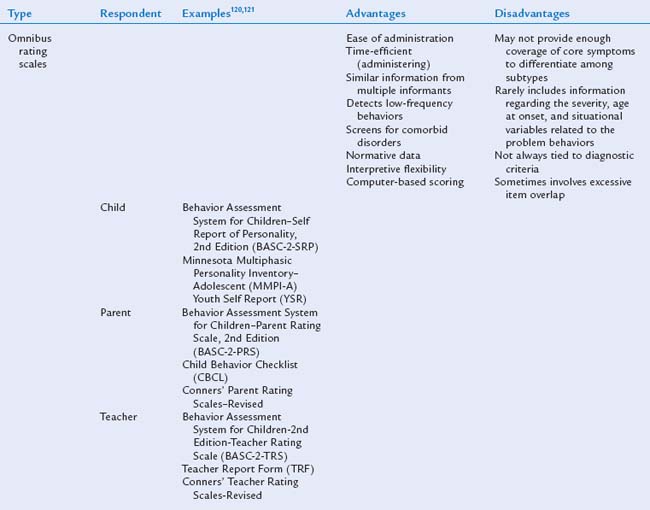

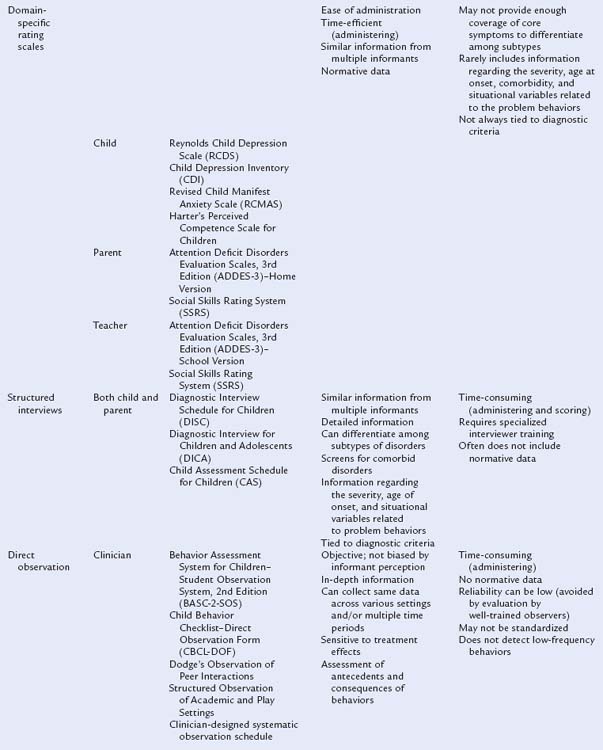

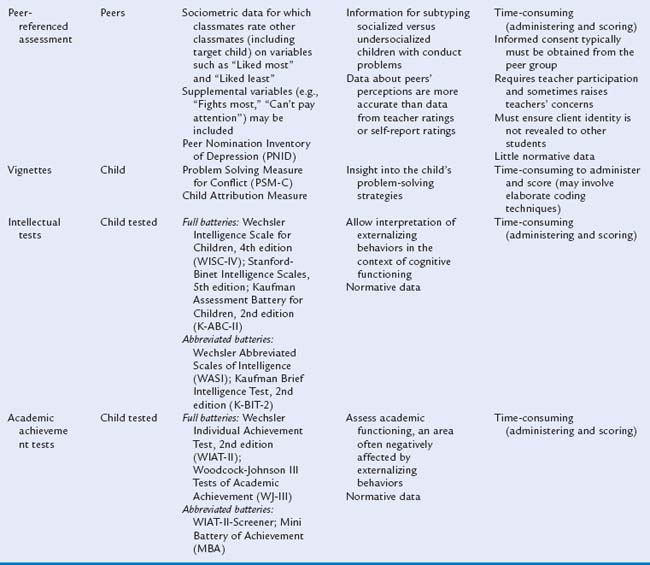

When a child is referred for an evaluation for externalizing behavioral problems, mental health specialists use an array of assessment tools to gather comprehensive information about the child. It is important that the assessment battery include data from multiple informants across multiple domains of functioning. It is also helpful if the informants observe the child in various settings, so that the clinician can draw conclusions about the consistency of the behaviors. For example, parents may be the best reporters of a child’s behavior at home and with siblings, whereas teachers provide insight into the child’s behavior at school and with peers. Child mental health professionals commonly use behavioral rating scales and structured interviews in their assessment of externalizing behaviors. In addition, direct behavioral observation by the clinician can supply objective data about the child’s behaviors in various contexts. In planning an assessment battery for a child presenting with externalizing behavior problems, it is important to assess also for comorbid problems and associated features, such as attentional difficulties, social skills deficits, and depressive symptoms. In a comprehensive assessment, it is important to have the child complete self-report rating scales (e.g., related to self-esteem, attitudes) if the child is old enough to be a reliable informant. Most children over the age of 8 years can provide valuable assessment data.120

Although teachers often have insight into peer relationship problems and the social functioning of children with externalizing behavior problems, it is also helpful for clinicians to obtain peer reports whenever possible. Vignettes and hypothetical situations are also used to assess social-cognitive processes, whereas intellectual and academic achievement tests are utilized to conduct a psychoeducational assessment.121 Table 17-2 contains examples of assessment instruments often included in a comprehensive diagnostic battery.

In addition to making a differential diagnosis, the use of a comprehensive assessment battery is important in determining which symptoms are primary and which are secondary.121 Identification of primary and secondary symptoms is an important first step in formulating an effective treatment plan. Once all assessment data are collected, the clinician compiles the information into a clinical assessment report, in which the data from various sources are integrated, the findings interpreted, the case formulation and diagnostic impressions outlined, and the treatment plan and recommendations for the child described. In the assessment report, the clinician should document clinically significant findings, including convergent findings across sources and methods, as well as explain any existing discrepancies among sources and methods.120 The report should provide a profile of the child that includes not only a discussion of any existing deficits and problems but also information about his or her strengths.

TREATMENT OF EXTERNALIZING CONDITIONS

Preadolescent children who exhibit disruptive and aggressive behavior are at increased risk for a host of negative outcomes, including severe delinquency, violence, substance abuse, school dropout, and co-occurring psychiatric disorders.122,123 Pediatricians can play a critical role in identifying such children and making appropriate treatment recommendations. There are numerous evidence-based interventions in which children with externalizing behavior disorders are treated effectively,124–126 and early intervention and prevention can significantly improve affected children’s developmental trajectory.116 However, young children with conduct problems are a chronically underserved population. Brestan and Eyberg127 found that only about 30% of children with conduct problems received any treatment and even fewer received treatments that had been empirically validated in randomized controlled trials. Pediatricians are often the first professionals to learn of disruptive behavior in children; thus, they can play a critical role in identifying children in need and providing appropriate treatment recommendations.

Systematic reviews of the treatment literature have identified a number of intervention programs with well-established therapeutic effects for children with externalizing behavior disorders.126,127 All of the programs shown to effectively reduce disruptive and aggressive behavior in children involve the use of cognitive and behavioral treatment techniques. These treatment programs vary in their emphasis on parents and/or children; interventions for preschool-aged children focus on parent behavioral training, and interventions for school-aged children and adolescents entail teaching skills, including social problem solving, coping with anger, perspective taking, and relaxation. Multicomponent interventions that target parents and children, as well as teachers and other key adults, consistently produce stronger therapeutic effects and better maintenance of improvements over time than do interventions that focus on either the child or parent alone.126

Two treatment approaches are considered “well established” because of their extensive empirical support. Both originated as parent training programs and were subsequently expanded to include child-focused intervention components. The first is behavioral parent training based on Patterson and Gullion’s manual Living with Children: New Methods for Parents and Teachers.128 This approach is designed to teach parents operant conditioning techniques to increase prosocial behaviors in children and decrease aggressive and disruptive behaviors. These techniques include attending to and reinforcing prosocial and compliance behaviors; ignoring minor disruptive behaviors; implementing negative consequences after inappropriate behaviors (such as timeout and privilege removal); and giving effective commands. Kazdin129 developed a parent management training program based on Patterson and Gullion’s work and paired it with a child-focused problem-solving skills training program, which teaches children social problem-solving skills through modeling, role-play, and practice. Although both parent management training and problem-solving skills training can be used as stand-alone interventions, combined treatment tends to be more effective than either treatment alone.130

The second “well-established” treatment approach is a similar behavioral parent training program developed by Webster-Stratton131,132 known as the Incredible Years Training Series. It includes video segments that model parent training, typically viewed in a therapist-led group. During these group sessions, parents view and discuss video vignettes demonstrating social learning and child development principles and how parents can use child-directed techniques—interactive play, praise, and incentive programs—and nonviolent discipline techniques. An advanced version of the program incorporates video vignettes promoting parents’ personal self-control, communication skills, problem-solving skills, social support, and self-care. Webster-Stratton also developed a child videotape modeling program and teacher training curriculum, which have been shown to enhance outcome effects of the original Incredible Years parent training program.133,134

Another evidence-based intervention, parent-child interaction therapy, was specifically designed to target the parent and child dyad, with the therapist serving as a coach during in-person encounters to improve the parent and child’s interaction patterns.135 Operant conditioning parenting techniques similar to those described previously are taught by this coaching method, including a specific system for implementing timeout after a child disobeys a command. Parent-child interaction therapy is used most often with families of preschool-aged children (i.e., between the ages of 3 and 6). Significant improvements in children’s behavior, parenting stress, and parents’ perceptions of control are found in families receiving parent-child interaction therapy in relation to families in a waitlist control group. Moreover, these gains are maintained after treatment completion and generalize to children’s classroom behavior.135

More comprehensive family and community-based treatments are often needed when multiple risk factors are present (e.g., child maltreatment, marital discord, parental psychopathology, poverty, exposure to neighborhood violence) and for adolescents with serious behavior problems. Multisystemic therapy is an intensive family and community-based treatment program that has been implemented with chronic and violent juvenile offenders, substance-abusing juvenile offenders, adolescent sexual offenders, youths in psychiatric crisis (i.e., homicidal, suicidal, psychotic), and maltreating families.136 The Oregon Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care program is also a comprehensive and systemic intervention designed to treat adolescent juvenile offenders in nonrestrictive, family-style, community-based settings.137 Both multisystemic therapy and the Oregon program have demonstrated effectiveness in treating chronically delinquent youth and, in many cases, in changing youths’ behavior and creating safer and more positive family living environments.125

With any intervention program for children and adolescents with externalizing behavior problems, treatment is most effective when modifications are consistent across settings. Consultation with teachers and other school personnel is crucial for tailoring interventions to children’s individual needs and ensuring that they receive appropriate academic and behavioral services at school. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, children with externalizing behavior problems that adversely affect their school performance are eligible for an Individualized Education Plan or a Section 504 Plan that establishes target behavioral goals and needed interventions (e.g., classroom behavior chart, home-to-school notebook for daily behavior tracking). Pediatricians can play a critical role in educating parents about their child’s right to school-based services and encouraging them to work closely with their child’s school to ensure that he or she is obtaining the behavioral supports necessary to learn.

Coping Power Program

Many of the evidence-based intervention programs just described incorporate similar cognitive and behavioral treatment techniques. To provide a more detailed description of these intervention elements, we now describe the Coping Power program. Coping Power is a comprehensive, multicomponent intervention program that is based on the contextual social-cognitive model of risk for youth violence.138 Coping Power draws upon many of the cognitive and behavioral techniques of well-established parent training programs and also incorporates novel techniques that target malleable, child-level social-cognitive risk factors for externalizing behavior problems. We describe the content of the Coping Power program in detail to illustrate the structure and skills taught in a comprehensive, multicomponent, evidence-based intervention for preadolescent children exhibiting disruptive and aggressive behavior.

COPING POWER CHILD COMPONENT

The Coping Power Child Component includes 34 group sessions, each lasting 45 to 60 minutes. The optimal number of children per group is 4 to 6, with two coleaders. Group sessions are held approximately once a week and are supplemented by monthly individual meetings with each child. The primary aims of the one-to-one sessions are to monitor and reinforce each child’s progress toward personal social behavior goals (e.g., avoiding fights with peers; resisting peer pressure) and to encourage generalization of intervention effects to other settings. The Coping Power Child Component is an expanded version of the original 18-session Anger Coping Program.139

The sequence and objectives of the Coping Power Child Component group sessions are detailed in Table 17-3. The foci of the child group sessions include (1) establishing group rules and a reinforcement contingency; (2) personal behavioral goal setting; (3) awareness of anger arousal and learning to use coping self-statements, relaxation, and distraction techniques to cope with arousal; (4) practicing accurate problem identification and social perspective taking with pictured and actual social problem situations; (5) generating alternative solutions to social problems, considering the consequences of each solution, and selecting and enacting the optimal solution; (6) viewing modeling videotapes of children becoming aware of physiological arousal when angry, using self-statements (“Stop! Think! What should I do?”), and using the complete set of problem-solving skills to effectively solve social problems; (7) facilitating the children’s production of a videotape demonstrating effective problem solving with social problems of their own choosing; (8) enhancing social skills and methods for identifying and entering positive peer networks (focusing on cooperation and negotiation skills during structured and unstructured peer interactions); and (9) learning and rehearsing strategies for resisting peer pressure.

| Session and Topic | Session Goals |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | |

| Getting acquainted/group cohesion | |

COPING POWER PARENT COMPONENT

The Coping Power Parent Component includes 16 group sessions, each lasting approximately 90 minutes. Parents meet in groups of up to 12 parents (or parent dyads) with two coleaders. Parent group sessions are held within the same time period in which the child group sessions occur. The content of the Coping Power Parent Component is derived from social learning theory–based parent training programs such as those described previously.2,128 Specifically, the parents learn skills for (1) identifying prosocial and disruptive target behaviors in their children; (2) rewarding appropriate child behaviors; (3) giving effective instructions and establishing age-appropriate rules and expectations for their child in the home; (4) applying effective nonphysical consequences to negative child behaviors; (5) managing child behavior outside the home; and (6) establishing ongoing family communication structures in the home (such as weekly family meetings).

The sequence and objectives of the Coping Power Parent Component group sessions are detailed in Table 17-4. Each session follows a similar format, opening with discussion, reactions, and questions about the previous session; presentation of new session content; discussion with parents about their reactions to the new content; eliciting parents’ ideas about how to adapt content to their particular situation; and homework assignment. Similar to the child groups, role-plays and in-session activities, as well as homework assignments, are used to facilitate transfer of skills learned to the home environment and other settings.

| Session and Topic | Session Goals |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | |

| Program orientation | |

COPING POWER TEACHER COMPONENT

The Coping Power teacher curriculum is typically provided during in-service workshops. During the workshops, didactic presentations are combined with teacher discussion and problem solving around the presentation topic. The foci of the teacher meetings include (1) critical challenges that arise at the time of the middle school transition and ways in which parents and teachers can help children prepare to make this transition successfully; (2) methods for promoting positive parent involvement in the school setting and in their child’s education; (3) enhancing children’s study skills, ability to organize work, and completion of homework, including a focus on children’s self control, the parent-teacher communications regarding homework, and children’s social bond to school; (4) enhancing children’s social competence by emphasizing teacher facilitation of children’s emerging social problem-solving strategies; and (5) enhancing children’s self-control and self-regulation through conflict management strategies involving peer negotiation and teacher’s use of proactive classroom management.

Outcome Effects of Coping Power and Anger Coping Programs

In efficacy and effectiveness studies, the Coping Power program has been found to produce lower rates of parent-reported youth substance abuse and self-reported delinquent behavior after intervention and at a 1-year follow-up, in comparison with a randomly assigned control group,48 and lower self-reported substance abuse, reductions in proactive aggression, improvements in social competence, and greater teacher-rated behavioral improvement at the end of the intervention, in comparison with children who had not received Coping Power.140 The Anger Coping Program from which the Coping Power Child Component was derived has also been shown to produce lasting social-cognitive gains and to prevent substance abuse into adolescence141; however, the adjunctive parent intervention component appears to be necessary in order to have longer term effects on children’s delinquent behavior. This is consistent with similar studies that have revealed that multicomponent interventions (i.e., with both parent and child intervention components) can be the most effective for children with externalizing behavior problems.130,133

Follow-up by the Pediatrician

A wealth of developmental research makes it clear that without intervention, preadolescent children exhibiting disruptive behavior and aggression are at significant risk for a host of negative outcomes, as described previously.122,123 The pediatrician should therefore remain actively involved with families once conduct problems are identified. Roles of the pediatrician can include monitoring parents’ motivation to seek assessment and treatment, reinforcing parents and children for their effort to learn positive parenting and coping skills, recognizing individual differences that may affect the selection and course of treatment, collaborating with multidisciplinary service providers, and determining whether medication treatment for coexisting psychiatric conditions is warranted. It is important for pediatricians, when making treatment recommendations and referrals, to consider the developmental trajectory of aggressive and oppositional behaviors, including determining whether specific behaviors are age appropriate.

1 Achenbach TM, Howell CT. Are American children’s problems getting worse? A 13-year comparison. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:1145-1154.

2 McMahon RJ, Forehand RL. Helping the Noncompliant Child: Family-Based Treatment for Oppositional Behavior, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2003.

3 Schoen SF. The status of compliance technology: Implications for programming. J Spec Educ. 1983;17:483-496.

4 Brumfield BD, Roberts MW. A comparison of two measurements of child compliance with normal preschool children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:109-116.

5 Lahey BB, Schwab-Stone M, Goodman SH, et al. Age and gender differences in oppositional behavior and conduct problems: A cross-sectional household study of middle childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:488-503.

6 Vaughn BE, Kopp CB, Krakow JB. The emergence and consolidation of self-control from eighteen to thirty months of age: Normative trends and individual differences. Child Dev. 1984;55:990-1004.

7 Kochanska G, Coy KC, Murray KT. The development of self-regulation in the first four years of life. Child Dev. 2001;72:1091-1111.

8 Kuczynski L, Kochanska G. Development of children’s noncompliance strategies from toddlerhood to age 5. Dev Psychol. 1990;26:398-408.

9 Smith CL, Calkins SD, Keane SP, et al. Predicting stability and change in toddler behavior problems: Contributions of maternal behavior and child gender. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:29-42.

10 Patterson GR, Forgatch M. Parents and Adolescents: Living Together. Eugene, OR: Castalia, 1987.

11 Collins WA, Laursen B. Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. J Early Adolesc. 2004;24:55-62.

12 Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J Res Adolesc. 2001;11:1-19.

13 Laursen B, Coy KC, Collins WA. Reconsidering changes in parent-child conflict across adolescence: A meta-analysis. Child Dev. 1998;69:817-832.

14 Bongers IL, Koot HM, Van der Ende J, et al. Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 2004;75:1523-1537.

15 Dodge KA. The structure and function of reactive and proactive aggression. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991:201-218.

16 Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 1995;66:710-722.

17 Bohnert AM, Crnic KA, Lim KG. Emotional competence and aggressive behavior in school-age children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31:79-91.

18 Denham SA, Caverly S, Schmidt M, et al. Preschool understanding of emotions: Contributions to classroom anger and aggression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43:901-916.

19 Rydell A, Berlin L, Bohlin G. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and adaptation among 5- to 8-year-old children. Emotion. 2003;3:30-47.

20 Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, et al. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Dev Psychol. 2005;41:193-211.

21 Hanish LD, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, et al. The expression and regulation of negative emotions: Risk factors for young children’s peer victimization. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:335-353.

22 Stenberg CR, Campos JJ, Emde RN. The facial expression of anger in seven-month-old infants. Child Dev. 1983;54:178-184.

23 Huebner RR, Izard CE. Mothers’ responses to infants’ facial expressions of sadness, anger, and physical distress. Motiv Emotion. 1988;12:185-196.

24 Malatesta CZ, Grigoryev P, Lamb C, et al. Emotion socialization and expressive development in preterm and full-term infants. Child Dev. 1986;57:316-330.

25 Buss KA, Kiel EJ. Comparison of sadness, anger, and fear facial expressions when toddlers look at their mothers. Child Dev. 2004;75:1761-1773.

26 Dunn JF. Sibling influences on childhood development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1988;29:119-127.

27 Denham SA. Emotional Development in Young Children. New York: Guilford, 1998.

28 Ridgeway D, Waters E, Kuczaj SA. Acquisition of emotion-descriptive language: Receptive and productive vocabulary norms for ages 18 months to 6 years. Dev Psychol. 1985;21:901-908.

29 Shipman KL, Zeman J, Nesin AE, et al. Children’s strategies for displaying anger and sadness: What works with whom? Merrill Palmer Q. 2003;49:100-122.

30 Underwood M, Coie J, Herbsman CR. Display rules for anger and aggression in school-aged children. Child Dev. 1992;63:366-380.

31 Bongers IL, Koot HM, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:179-192.

32 Keiley MK, Bates JE, Dodge KA, et al. A cross-domain growth analysis: Externalizing and internalizing behaviors during 8 years of childhood. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2000;28:161-179.

33 Stanger C, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC. Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent syndromes. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9:43-58.

34 Lochman JE, Whidby JM, Fitzgerald DP. Cognitive-behavioral assessment and treatment with aggressive children. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2000:31-87.

35 Loeber R. Development and risk factors of juvenile antisocial behavior and delinquency. Clin Psychol Rev. 1990;10:1-41.

36 Olweus D. Bully/victims problems among schoolchildren: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. Development and Treatment of Childhood Aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991:411-448.

37 Rigby K. Bullying in Schools and What to Do about It. London: Jessica Kingsley, 1996.

38 Farrington DP. Understanding and preventing bullying. Tonry M, editor. Crime and Justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993;17:381-458.

39 Ireland JL, Archer J. Association between measures of aggression and bullying among juvenile and young offenders. Aggress Behav. 2004;30:29-42.

40 Nabuzoka D, Smith PK. Sociometric status and social behavior of children with and without learning difficulties. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34:1435-1448.

41 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2000.

41a Wolraich M, Felice ME, Drotar D. The Classification of Child and Adolescent Mental Diagnoses in Primary Care: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC) Child and Adolescent Version. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1996.

42 Barry CT, Frick PJ, DeShazo TM, et al. The importance of callous-unemotional traits for extending the concept of psychopathy to children. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:335-340.

43 Cleckley H. The Mask of Insanity, 5th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1976.

44 Hart RD, Hare RD. Psychopathy: Assessment and association with criminal conduct. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of Antisocial Behavior. New York: Wiley; 1997:22-35.

45 Hinshaw SP, Lee SS. Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child Psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2003:144-198.

46 Hinshaw SP, Lahey BB, Hart EL. Issues of taxonomy and comorbidity in the development of conduct disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5:31-49.

47 Loeber R, Green SM, Keenan K, et al. Which boys will fare worse?: Early predictors of the onset of conduct disorder in a six-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:499-509.

48 Lochman JE, Wells KC. Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power Program. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14:971-993.

49 Lochman JE. Contextual factors in risk and prevention research. Merrill Palmer Q. 2004;50:311-325.

50 Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Mednick SA. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and adult male criminal outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:215-219.

51 Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Templin T, et al. Teacher-assessed behavior of children prenatally exposed to cocaine. Pediatrics. 2000;106:782-791.

52 Kelly JJ, Davis PO, Henschke PN. The drug epidemic: Effects on newborn infants and health resource consumption at a tertiary perinatal centre. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:262-264.

53 Rasanen P, Hakko H, Isobarmi M, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of criminal behavior among male offspring in the northern Finland 1996 birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:857-862.

54 Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Dev Psychopathol. 1990;2:425-444.

55 Arseneault L, Tremblay RE, Boulerice B, et al. Obstetric complications and adolescent violent behaviors: Testing two developmental pathways. Child Dev. 2002;73:496-508.

56 Coon H, Carey G, Corley R, et al. Identifying children in the Colorado adoption project at risk for conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:503-511.

57 Dabbs JM, Morris R. Testosterone, social class, and antisocial behavior in a sample of 4,462 men. Psychol Science. 1990;1:209-211.

58 Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick SA. Interactions between birth complications and early maternal rejection in predisposing individuals to adult violence: Specificity to serious, early onset violence. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1265-1271.

59 Scarpa A, Bowser FM, Fikretoglu D, et al. Effects of community violence II: Interactions with psycho-physiologic functioning. Psychophysiology. 1999;36(Suppl):102.

60 Scarpa A, Raine A. Violence associated with anger and impulsivity. In: Borod JC, editor. The Neuropsychology of Emotion. London: Oxford University Press; 2000:320-339.

61 Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt T, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297:851-854.

62 Colder CR, Lochman JE, Wells KC. The moderating effects of children’s fear and activity level on relations between parenting practices and childhood symptomatology. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25:251-263.

63 Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children’s negative emotional reactivity. Soc Dev. 2003;12:420-439.

64 Barry TD, Dunlap ST, Cotton SJ, et al. The influence of maternal stress and distress on disruptive behavior problems in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:265-273.

65 Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Development of juvenile aggression and violence: Some common misconceptions and controversies. Am Psychol. 1998;53:242-259.

66 McCarty CA, McMahon RJ, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing and disruptive behavior Disorders. J Fam Psychol. 2003;17:545-556.

67 Sampson JH, Laub RJ. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

68 Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Tolan PH, et al. Stressful events and individual beliefs as correlates of economic disadvantage and aggression among urban children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:513-528.

69 Nagin D, Pogarsky G, Farrington D. Adolescent mothers and the criminal behavior of their children. Law Soc. 1997;31:137-162.

70 Erath SA, Bierman KL. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group: Aggressive marital conflict, maternal harsh punishment, and child aggressive-disruptive behavior: Evidence for direct and indirect relations. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:217-226.

71 Shaw DS, Vondra JI. Infant attachment security and maternal predictors of early behavior problems: A longitudinal study of low-income families. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995;26:407-414.

72 Luthar SS. Children in Poverty: Risk and Protective Factors in Adjustment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999.

73 Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Dev. 1994;65:649-665.

74 Dadds MR, Powell MB. The relationship of interpa-rental conflict and global marital adjustment to aggression, anxiety, and immaturity in aggressive and nonclinic children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1992;19:553-567.

75 Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial Boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia, 1992.

76 Shaw DS, Keenan K, Vondra JI. The developmental precursors of antisocial behavior: Ages 1–3. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:355-364.

77 Weiss B, Dodge KA, Bates JE, et al. Some consequences of early harsh discipline: Child aggression and maladaptive social information processing style. Child Dev. 1992;63:1321-1335.

78 Fite PJ, Colder CR, Lochman JE, et al. The mutual influence of parenting and boys’ externalizing behavior problems. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2006;27:151-164.

79 Haapasalo J, Tremblay R. Physically aggressive boys from ages 6 to 12: Family background, parenting behavior, and prediction of delinquency. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:1044-1052.

80 Cillessen AH, Van I Jzendoorn HW, Van Lieshout CF, et al. Heterogeneity among peer-rejected boys: Subtypes and stabilities. Child Dev. 1992;63:893-905.

81 Lochman JE, Wayland KK. Aggression, social acceptance and race as predictors of negative adolescent outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:1026-1035.

82 Miller-Johnson S, Coie JD, Maumary-Gremaud A, et al. Peer rejection and aggression and early starter models of conduct disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30:217-230.

83 Bry BH, Catalano RF, Kumpfer K, et al. Scientific findings from family prevention inter vention research. In: Ashery R, editor. Family-Based Prevention Interventions. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse; 1999:103-129.

84 Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The Fast Track experiment: Translating the developmental model into a prevention design. In: Kupersmidt JB, Dodge KA, editors. Children’s Peer Relations: From Development to Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:181-208.

85 Pardini DA, Barry TD, Barth JM, et al. Self-perceived social acceptance and peer social standing in children with aggressive-disruptive behaviors. Soc Dev. 2006;15:46-64.

86 Miller-Johnson S, Coie JD, Maumary-Gremaud A, et al. Relationship between childhood peer rejection and aggression and adolescent delinquency severity and type among African American youth. J Emot Behav Disord. 1999;7:137-146.

87 Dishion TJ, Andrews DW, Crosby L. Antisocial boys and their friends in early adolescence: Relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional process. Child Dev. 1995;66:139-151.

88 Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Pagani L, et al. Disruptive behavior, peer association, and conduct disorder: Testing the developmental links through early intervention. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:287-304.

89 Kupersmidt JB, Griesler PC, DeRosier ME, et al. Childhood aggression and peer relations in the context of family and neighborhood factors. Child Dev. 1995;66:360-375.

90 Colder CR, Mott J, Levy S, et al. The relation of perceived neighborhood danger to childhood aggression: A test of mediating mechanisms. Am J Comm Psychol. 2000;28:83-103.

91 Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Dev. 2003;74:1561-1576.

92 Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS. Neighborhood contextual factors and early-starting antisocial pathways. Clin Child Fam Psychol. 2002;5:21-55.

93 Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, et al. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks and danger on parental behaviors. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63:941-953.

94 Greenberg MT, Lengua LJ, Coie JD, et al. Predicting developmental outcomes at school entry using a multiple-risk model: Four American communities. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:403-417.

95 Schwab-Stone ME, Ayers TS, Kasprow W, Voyce C, Barone C, Shriver T, Weissberg RP. No safe haven: A study of violence exposure in an urban community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1343-1352.

96 Barth JM, Dunlap ST, Dane H, et al. Classroom environment influences on aggression, peer relations, and academic focus. J School Psychol. 2004;42:115-133.

97 Kellam SG, Ling X, Mersica R, et al. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course of malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:165-185.

98 Dodge KA, Laird R, Lochman JE, et al. Multidimensional latent construct analysis of children’s social information processing patterns: Correlations with aggressive behavior problems. Psychol Assess. 2002;14:60-73.

99 Pardini D, Lochman JE, Wells KC. Negative emotions and alcohol use initiation in high-risk boys: The moderating effect of good inhibitory control. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2004;32:505-518.

100 Williams SC, Lochman JE, Phillips NC, et al. Aggressive and nonaggressive boys’ physiological and cognitive processes in response to peer provocations. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:568-576.

101 Lochman JE, Dodge KA. Social-cognitive processes of severely violent, moderately aggressive, and nonaggressive boys. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:366-374.

102 Dodge KA, Pettit GS, McClaskey CL, et al. Social competence in children. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1986;51:1-85.

103 Gouze KR. Attention and social problem solving as correlates of aggression in preschool males. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1987;15:181-197.

104 Milich R., Dodge KA. Social information processing in child psychiatric populations. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984;12:471-489.

105 Dodge KA, Lochman JE, Harnish JD, et al. Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:37-51.

106 Lochman JE, Wayland KK, White KJ. Social goals: Relationship to adolescent adjustment and to social problem solving. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21:135-151.

107 Joffe RD, Dobson KS, Fine S, et al. Social problem-solving in depressed, conduct-disordered, and normal adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1990;18:565-575.

108 Lochman JE, Lampron LB. Situational social problem-solving skills and self-esteem of aggressive and nonaggressive boys. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1986;14:605-617.

109 Rabiner DL, Lenhart L, Lochman JE. Automatic vs. reflective social problem solving in relation to children’s sociometric status. Dev Psychol. 1990;26:1010-1026.

110 Pepler DJ, Craig WM, Roberts WI. Observations of aggressive and nonaggressive children on the school playground. Merrill Palmer Q. 1998;44:55-76.

111 Dunn SE, Lochman JE, Colder CR. Social problem-solving skills in boys with conduct and oppositional disorders. Aggress Behav. 1997;23:457-469.

112 Crick NR, Werner NE. Response decision processes in relational and overt aggression. Child Dev. 1998;69:1630-1639.

113 Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Frick PJ. Callous/unemotional traits and social cognitive processes in adjudicated youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:364-371.

114 Zelli A, Dodge KA, Lochman JE, et al. The distinction between beliefs legitimizing aggression and deviant processing of social cues: Testing measurement validity and the hypothesis that biased processing mediates the effects of beliefs on aggression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:150-166.

115 Lochman JE, Magee TN, Pardini D. Cognitive behavioral interventions for children with conduct problems. In: Reinecke M, Clark D, editors. Cognitive Therapy over the Lifespan: Theory, Research and Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003:441-476.

116 Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Outcome effects at the one-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:571-578.

117 Barry TD, Thompson A, Barry CT, et al: The importance of narcissism in predicting proactive and reactive aggression in moderately to highly aggressive children. Aggress Behav, in press.

118 Lochman JE, Nelson WMIII, Sims JP. A cognitive behavioral program for use with aggressive children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1981;10:146-148.

119 Lochman JE, Dodge KA. Distorted perceptions in dyadic interactions of aggressive and nonaggressive boys: Effects of prior expectations, context, and boys’ age. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10:495-512.

120 Kamphaus RW, Frick PJ. Clinical Assessment of Child and Adolescent Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 2001.

121 Lochman JE, Dane HE, Magee TN, et al. Disruptive behavior disorders: Assessment and intervention. In: Vance B, Pumareiga A, editors. The Clinical Assessment of Children and Youth: Interfacing Intervention with Assessment. New York: Wiley; 2001:231-262.

122 Loeber R, Farrington DP. The significance of child delinquency. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Child Delinquents: Development, Intervention, and Service Needs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001:1-22.

123 Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Yoerger K. Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro-and micro-peer dynamics. Prev Sci. 2000;1:3-13.

124 Hibbs ED, Jensen PS. Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Disorders: Empirically Based Strategies for Clinical Practice, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2005.

125 Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford, 2003.

126 Lochman JE, Salekin RT. Prevention and intervention with aggressive and disruptive children: Next steps in behavioral intervention research. Behav Ther. 2003;34:413-419.

127 Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:180-189.

128 Patterson GR, Gullion ME. Living with Children: New Methods for Parents and Teachers. Champaign, IL: Research Press, 1968.

129 Kazdin AE. Problem-solving skills training and parent management training for conduct disorder. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2003:241-262.

130 Kazdin AE, Siegel T, Bass D. Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:733-747.

131 Webster-Stratton C. Randomized trial of two parent-training programs for families with conduct-disordered children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:666-678.

132 Webster-Stratton C. Advancing videotape parent training: A comparison study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:583-593.

133 Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:93-109.

134 Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. The Incredible Years Parents, Teachers, and Children Training Series. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2003:224-240.

135 Brinkmeyer MY, Eyberg SM. Parent-child interaction therapy for oppositional children. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2003:204-223.

136 Henggeler SW, Lee T. Multisystemic treatment of serious clinical problems. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2003:301-322.

137 Chamberlain P, Smith DK. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: The Oregon Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care Model. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2003:282-300.

138 Lochman JE, Wells KC, Murray M. The Coping Power program: Preventive intervention at the middle school transition. In: Tolan P, Szapocznik J, Sambrano S, editors. Preventing Substance Abuse: 3 to 14. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007:185-210.

139 Larson J, Lochman JE. Helping Schoolchildren Cope with Anger: A Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention. New York: Guilford, 2002.

140 Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power program at the middle school transition: Universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16:S40-S54.

141 Lochman JE. Cognitive-behavioral intervention with aggressive boys: Three year follow-up and preventive effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:426-432.