CHAPTER 26 External skull

The skull is the bony skeleton of the head. It shields the brain, the organs of special sense and the cranial parts of the respiratory and digestive systems, and provides attachments for many of the muscles of the head and neck. Movement of the lower jaw (mandible) occurs at the temporomandibular joint.

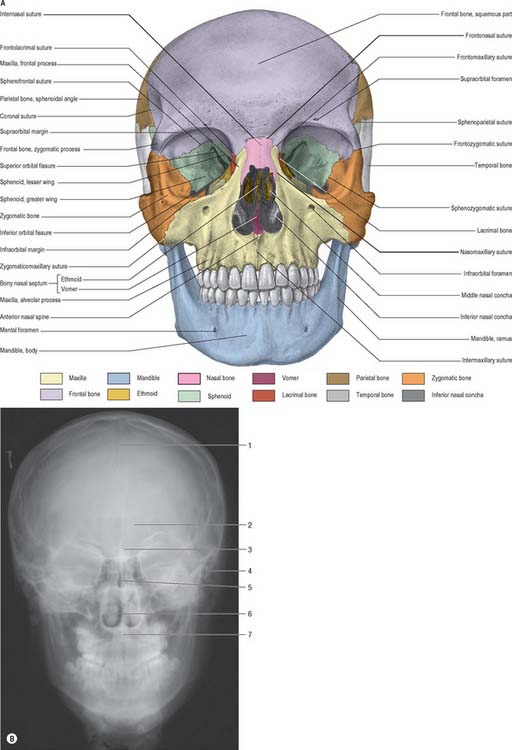

FRONTAL (ANTERIOR) VIEW

Viewed from the front, the skull is generally ovoid in shape and is wider above than below (Fig. 26.1). The upper part is formed by the frontal bone which underlies the forehead region above the orbits. Superomedial to each orbit is a rounded superciliary arch (more pronounced in males) between which there may be a median elevation, the glabella. The glabella may show the remains of the inter-frontal (metopic) suture, which is present in about 9% of adult skulls. Above each superciliary arch is a slightly elevated frontal tuber or eminence which is generally more obvious in the female. Below, where the nasal bones meet the frontal bone, is a depression marking the root of the nose. The frontal bone articulates with the two nasal bones at the frontonasal sutures; the point at which the frontonasal and internasal sutures meet is the anthropometric landmark known as the nasion.

A (From Sobotta 2006.) (B by courtesy of Mr Eric Whaites, Dental Institute, King’s College, London.)

The upper part of the face is occupied by the orbits and the bridge of the nose. Each orbital opening is approximately quadrangular (see Ch. 39). The upper, supraorbital, margin is formed entirely by the frontal bone, interrupted at the junction of its sharp lateral two-thirds and rounded medial third by the supraorbital notch or foramen, which transmits the supraorbital vessels and nerve. The lateral margin of the orbit is formed largely by the frontal process of the zygomatic bone and is completed above by the zygomatic process of the frontal bone; the suture between them lies in a palpable depression. The infraorbital margin is formed by the zygomatic bone laterally and maxilla medially. Both lateral and infraorbital margins are sharp and palpable. The medial margin of the orbit is formed above by the frontal bone and below by the lacrimal crest of the frontal process of the maxilla.

The anterior nasal aperture is piriform in shape, and is wider below than above and bounded by the nasal bones and maxillae. The upper boundary of the aperture is formed by the nasal bones while the remainder is formed by the maxillae. In life, various cartilages (septal, lateral nasal, major and minor alar) help to delineate two nasal cavities (see Ch. 32). The defleshed skull presents a single anterior nasal aperture because these cartilages are lost during preparation or decomposition. However, the shape of these bones can be used quite successfully to predict the shape of the cartilaginous nose.

AP radiographs of the skull clearly show the central location of the paranasal air sinuses in the frontal bone, the maxilla and the ethmoid. These can be particularly useful indicators of identity when postmortem images are compared with premortem clinical films.

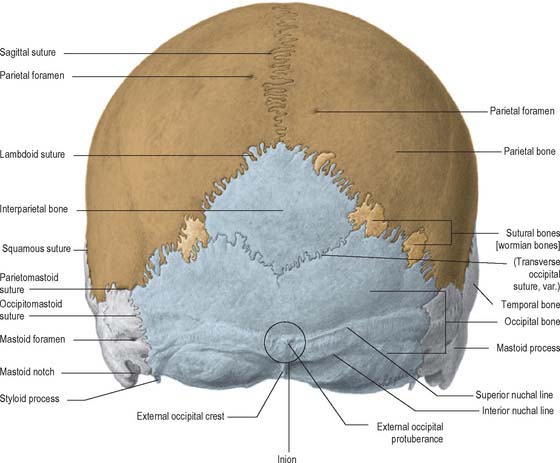

POSTERIOR VIEW

The parietal, temporal and occipital bones form the entirety of the posterior view (Fig. 26.2). The superolateral region is occupied by the parietal bones, the mastoid part of the temporal bones comprises the inferolateral regions and the central portion is occupied by the occipital bone, which is why this aspect is also referred to as the occipital view. The parietal bones articulate with the occipital bone at the lambdoid suture and extend inferiorly into the occipitomastoid and the parietomastoid sutures behind and above the mastoid process respectively. Sutural or wormian bones are islands of bone that are commonly found within the lambdoid suture. They may arise from separate centres of ossification and they appear to have no clinical significance, being of genetic rather than pathological aetiology. A large interparietal bone is not uncommon and is sometimes referred to as an Inca bone (Fig. 26.2).

The external occipital protuberance is a midline ridge or a distinct process on the occipital bone which can become particularly well developed in the male. Superior nuchal lines extend laterally from the protuberance and represent the boundary between the scalp and the neck. Inferior nuchal lines run parallel to, and below, the superior nuchal lines; a set of highest nuchal lines may sometimes occur above the superior lines. The external occipital protuberance, nuchal lines and roughened external surface of the occipital bone between the nuchal lines, all afford attachment to muscles of the neck.

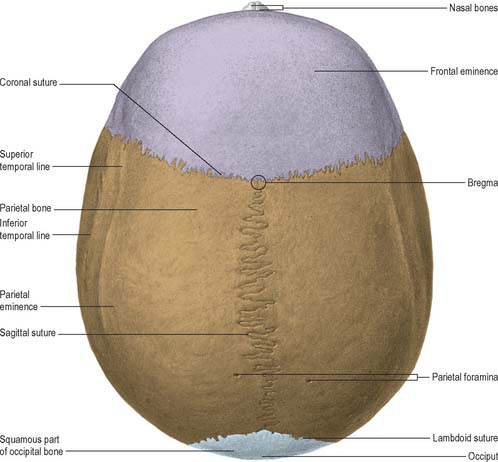

SUPERIOR VIEW

Seen from above, the contour of the cranial vault varies greatly but is usually ellipsoid, or more strictly, a modified ovoid with its greatest width lying nearer to the occipital pole (Fig. 26.3). Four bones constitute this view and articulate via three well-defined sutures. The squamous part of the frontal bone is anterior, the squamous part of the occipital bone is posterior and the two parietal bones meet in the midline and separate the frontal from the occipital bone. The maximal parietal convexity on each site is palpable at the parietal tuber or eminence: it is most conspicuous in the female who ostensibly retains a paedomorphic appearance. The superior and inferior temporal lines run close to the parietal eminence but are best seen in a lateral view.

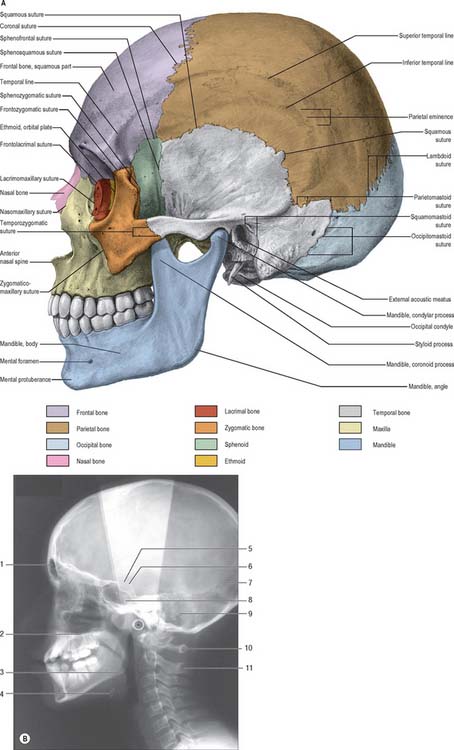

LATERAL VIEW

The skull, viewed from the side, can be subdivided into three zones: face (anterior); temporal region (middle); occipital region (posterior) (Fig. 26.4). The face has been considered in the section on the anterior view of the skull.

A (From Sobotta 2006.) (B by courtesy of Mr Eric Whaites, Dental Institute, King’s College, London.)

The lateral surface of the ramus of the mandible will be described briefly here as its position lies within the middle region of this view of the skull (see Ch. 31). The ramus is a plate of bone projecting upwards from the back of the body of the mandible; its lateral surface gives attachment to masseter. The ramus bears two prominent processes superiorly, the coronoid process anteriorly and condylar process posteriorly, separated by the mandibular notch. The coronoid process is the site of insertion of temporalis and the condylar process articulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone at the temporomandibular joint. The inferior and posterior borders of the mandible meet at the angle, which is often splayed in the male because of the larger site of muscle attachment for medial pterygoid on the internal surface.

The mandibular (glenoid) fossa is the part of the temporomandibular joint with which the condylar process of the mandible articulates. It is bounded in front by the articular eminence and behind by the tympanic plate. The articular eminence provides a surface over which the mandibular condyle glides during mandibular movements (see Ch. 31).

The tympanic plate of the temporal bone contributes most of the margin of the external acoustic (auditory) meatus, and the squamous part forms the posterosuperior region (see Ch. 36). The external margin is roughened to provide an attachment for the cartilaginous part of the meatus. A small depression, the suprameatal triangle, lies above and behind the meatus and is related to the lateral wall of the mastoid antrum.

The infratemporal fossa is an irregular postmaxillary space located deep to the ramus of the mandible; it communicates with the temporal fossa deep to the zygomatic arch (see Ch. 31). It is best visualized, therefore, when the mandible is removed but, for completeness, is considered here. Its roof is the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid. The lateral pterygoid plate lies medial to the fossa and the ramus of the mandible and styloid process lie laterally and posteriorly respectively. The infratemporal fossa has no anatomical floor. Its anterior and medial walls are separated above by the pterygomaxillary fissure lying between the lateral pterygoid plate and the posterior wall of the maxilla. The infratemporal fossa communicates with the pterygopalatine fossa through the pterygomaxillary fissure.

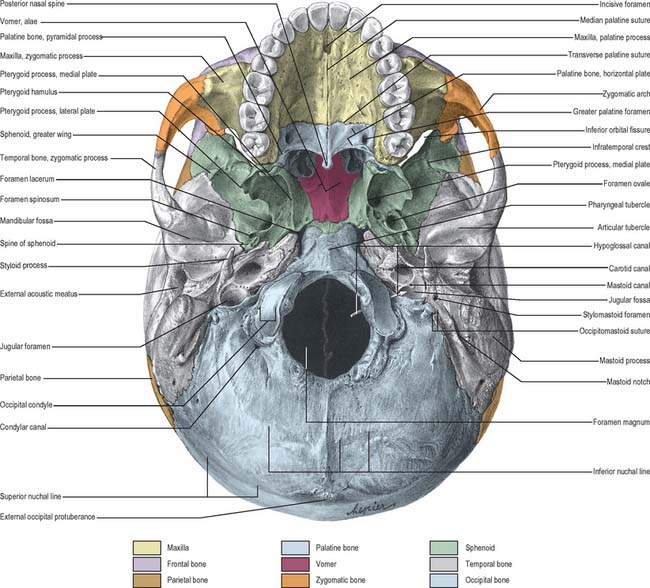

INFERIOR (BASAL) VIEW

The inferior surface of the skull, the base of the cranium, is complex: it extends from the upper incisor teeth anteriorly to the superior nuchal lines of the occipital bone posteriorly (Fig. 26.5). The region contains many of the foramina through which structures enter and exit the cranial cavity. The inferior surface can be conveniently subdivided into anterior, middle, posterior and lateral parts. The anterior part contains the hard palate and the dentition of the upper jaw and lies at a lower level than the rest of the cranial base. The middle and posterior parts can be arbitrarily divided by a transverse plane passing through the anterior margin of the foramen magnum. The middle part is occupied mainly by the base of the sphenoid bone, the apices of the petrous processes of the temporal bones and the basilar part of the occipital bone. The lateral part contains the zygomatic arches, mandibular fossa, tympanic plate and the styloid and mastoid processes. The posterior part lies in the midline and is exclusively formed from the occipital bone. Whereas the middle and posterior parts are directly related to the cranial cavity (the middle and posterior cranial fossae), the anterior part (the palate) is some distance from the anterior cranial fossa, being separated from it by the nasal cavities.

ANTERIOR PART OF CRANIAL BASE

The bony palate within the superior alveolar arch is formed by the palatine processes of the maxillae anteriorly and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones posteriorly, all meeting at a cruciform system of sutures (Fig. 26.5). The median palatine suture runs anteroposteriorly and divides the palate into right and left halves. This suture is continuous with the intermaxillary suture between the maxillary central incisor teeth. The transverse palatine (palatomaxillary) sutures run transversely across the palate between the maxillae and the palatine bones. The palate is arched sagittally and transversely: its depth and breadth are variable but are always greatest in the molar region. The incisive fossa lies behind the central incisor teeth, and the lateral incisive foramina, through which incisive canals pass to the nasal cavity, lie in its lateral walls. Median incisive foramina are present in some skulls and open onto the anterior and posterior walls of the fossa. The incisive fossa transmits the nasopalatine nerve and the termination of the greater palatine vessels. When median incisive foramina occur, the left nasopalatine nerve usually traverses the anterior foramen and the right nerve traverses the posterior foramen. The greater palatine foramen lies near the lateral palatal border of the transverse palatine suture; a vascular groove, deeper behind and shallower in front, leads forwards from the foramen. The lesser palatine foramina, usually two, lie behind the greater palatine foramen and pierce the pyramidal process of the palatine bone which is wedged between the lower ends of the medial and lateral pterygoid plates. The palate is pierced by many other small foramina and is marked by pits for palatine glands. Variably prominent palatine crests extend medially from behind the greater palatine foramina. The posterior border projects back as the posterior nasal spine. In the adult, the alveolar arch bears a maximum of 16 sockets or alveoli for the teeth: the sockets vary in size and depth, some are single and some are subdivided by septa, according to the morphology of the dental roots.

MIDDLE PART OF CRANIAL BASE

The middle part of the cranial base is made up from the body of the sphenoid, the petrous temporal bones and the basiocciput (Fig. 26.5). It extends from the posterior nares anteriorly to an artificial line drawn transversely through the anterior margin of the foramen magnum posteriorly. In the adult, the body of the sphenoid fuses with the basiocciput to form a midline bar of bone that extends posteriorly to the foramen magnum. The basilar part of the occipital bone bears a small midline pharyngeal tubercle, which gives attachment to the pharyngeal raphe and the highest attachment of the superior pharyngeal constrictor.

POSTERIOR PART OF CRANIAL BASE

The posterior part of the cranial base is largely formed by the occipital bone (Fig. 26.5). Prominent features are the foramen magnum and associated occipital condyles, jugular foramen, mastoid notch and squamous part of the occipital bone up to the external occipital protuberance and the superior nuchal lines, hypoglossal canals (anterior condylar canals) and condylar canals (posterior condylar canals).

Laterally, the occipital bone articulates with the petrous part of the temporal bone anteriorly at the petro-occipital suture, and the mastoid process of the temporal bone more posteriorly at the petromastoid suture. The jugular foramen, a large irregular hiatus, lies at the posterior end of the petro-occipital suture between the jugular process of the occipital bone and the jugular fossa of the petrous part of the temporal bone. A number of important structures pass through this foramen: inferior petrosal sinus (anterior); glossopharyngeal, vagus and accessory cranial nerves (middle); internal jugular vein (posterior). A mastoid canaliculus runs through the lateral wall of the jugular fossa and transmits the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. The canaliculus for the tympanic nerve branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve lies on the ridge between the jugular fossa and the opening of the carotid canal. A small notch, related to the inferior glossopharyngeal ganglion, may be found medially, on the upper boundary of the jugular foramen (it is more easily identified internally). The orifice of the cochlear canaliculus may be found at the apex of the notch.

The squamous part of the occipital bone exhibits the external occipital protuberance, supreme, superior and inferior nuchal lines, and the external occipital crest, all of which lie in the midline, posterior to the foramen magnum. The region is roughened for the attachment of muscles whose primary function is extension of the skull (see Ch. 42).

LATERAL PART OF CRANIAL BASE

The lateral part of the cranial base consists of the zygomatic arch and infratemporal fossa anteriorly and the mandibular fossa, tympanic plate and styloid and mastoid processes posteriorly (Fig. 26.5) – the anterior structures have been considered earlier in this chapter.

DISARTICULATED INDIVIDUAL BONES

Individual bones are described in appropriate chapters. The bones of the facial skeleton and cranial vault are described in the chapters on the face and scalp (29), nose and paranasal sinuses (32), external and middle ear (35) and orbit (39). The sphenoid and mandible are described in the chapter on the infratemporal fossa and the occipital bone is described in the chapter on the neck.

JOINTS

The general characteristics of cranial sutures and the detailed anatomy of the temporomandibular joint and the atlanto-occipital joints are described in Chapters 5, 31 and 42, respectively. Sutural bones are described below on page 418.

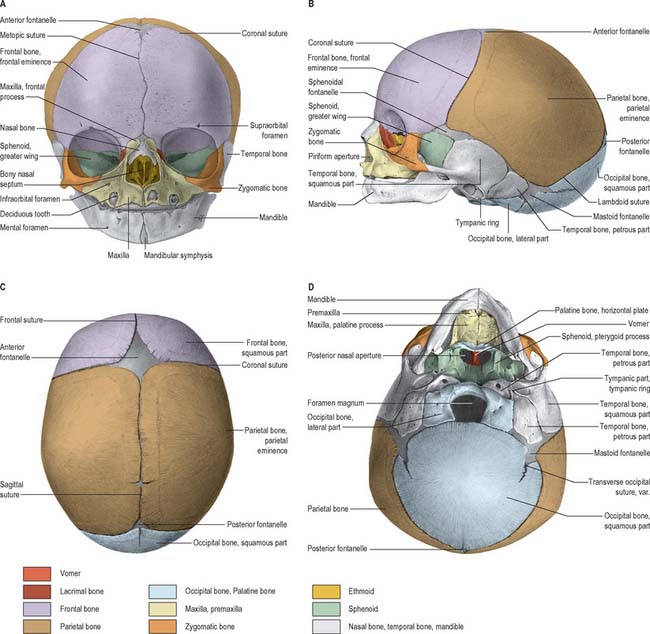

NEONATAL, PAEDIATRIC AND SENESCENT ANATOMY

THE SKULL AT BIRTH

At birth the skull is large in proportion to other skeletal parts; the facial region is relatively small and constitutes only about one-eighth of the neonatal cranium, compared with half in adult life (Fig. 26.6). Smallness of the face at birth is largely due to the rudimentary stage of development of the mandible and maxillae because the teeth are unerupted. The nose lies almost entirely between the orbits, and the lower border of the nasal aperture is only slightly lower in position than the orbital floors. The large size of the calvaria, especially the neurocranium, reflects precocious cerebral maturation. Bones of the cranial vault are unilaminar and lack diploë. Frontal and parietal tuberosities are prominent; in the frontal view, the greatest width occurs between the parietal tuberosities. The glabella, superciliary arches and mastoid processes are not developed and the cranial base is relatively short and narrow.

POSTNATAL GROWTH

Growth of the vault

Growth of the vault is rapid during the first year and then continues at a slower rate until the seventh year, when it has reached almost adult dimensions. For most of this period, expansion is largely concentric; overall form is determined early in the first year and remains largely unaltered thereafter. However, the shape of the vault is not solely related to cerebral growth, but is also influenced by genetic factors that manifest in an extensive range of shapes and sizes that may be sufficient to allow a reliable evaluation of racial origin. During the first and early second year, growth of the vault occurs primarily through ossification at apposed margins of bones (which possess an osteogenic layer) accompanied by some accretion and absorption of bone at surfaces in order to adapt to continually altering curvatures. Growth in breadth is said to occur at the sagittal, sphenofrontal, sphenotemporal, occipitomastoid and petro-occipital junctions, while growth in height is said to occur at the frontozygomatic and squamosal sutures, pterion and asterion. During this period, fontanelles are closed by progressive ossification of the bones around them, but separate rogue centres of ossification may develop into sutural bones. The sphenoidal and posterior fontanelles ossify within 2 or 3 months of birth, the mastoid fontanelles usually ossify near the end of the first year and the anterior fontanelle ossifies around the middle of the second year. Those fontanelles which close first are most likely to show sutural bones.

Growth of the face

Growth of the facial skeleton occurs over a longer time period than is witnessed for the calvaria. The ethmoid and the orbital and upper nasal cavities have almost completed growth by the seventh year. Orbital and upper nasal growth is achieved by sutural accretion, with deposition of bone preferentially occurring on the facial aspects of the sutural junctions. The maxilla is carried downwards and forwards by expansion of the orbits and nasal septum and by sutural growth, especially at the fontanelles and zygomaticomaxillary and pterygomaxillary sutures. In the first year, growth in width occurs at the symphysis menti and midpalatal, internasal and frontal sutures: such growth diminishes or even ceases when the symphysis menti and frontal suture close during the first few years, even though the midpalatal suture persists until mature years. Facial growth continues up to puberty and shows a period of expansion that is linked to the growth spurt and hormonal influences of secondary sexual alteration. After sutural growth, near the end of the second year, expansion of the facial skeleton occurs by surface accretion on the face, alveolar processes and palate, and resorption in the walls of the maxillary sinuses, the upper surface of the hard palate and the labial aspect of the alveolar process. Co-ordinated growth and divergence of the pterygoid processes reflects deposition and resorption of bone on appropriate surfaces.

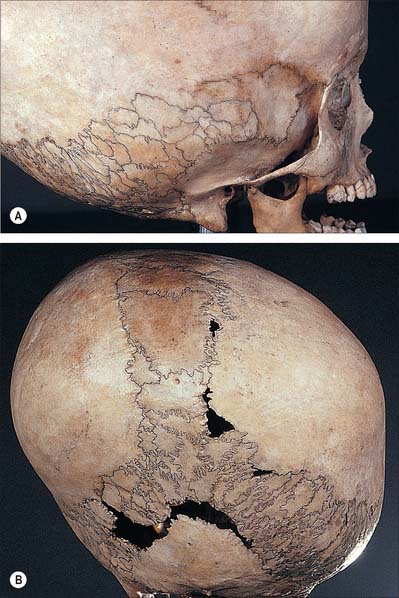

Sutural bones

Additional ossification centres may occur in or near sutures, giving rise to isolated sutural bones (also called Wormian bones, Fig. 26.2). Usually irregular in size and shape, and most frequent in the lambdoid suture, they frequently occur at fontanelles, especially the posterior fontanelle. They may represent a pre-interparietal element, a true interparietal, or some composite. An isolated bone at the lambda is sometimes referred to as an Inca bone or Goethe’s ossicle. One or more pterion ossicles or epipteric bones may appear between the sphenoidal angle of the parietal and the greater wing of the sphenoid; they vary greatly in size but are more or less symmetrical. Sutural bones usually have little morphological significance. However, they appear in great numbers in hydrocephalic skulls (Fig. 26.7), and they have therefore been linked with rapid cranial expansion. For a detailed analysis of these and other epigenetic variations in adult crania, consult Berry & Berry (1967) and Berry (1975).

Craniosynostosis

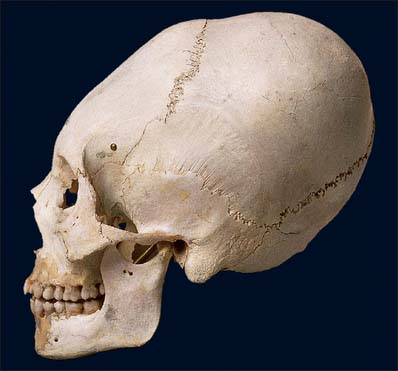

Skull deformities can also be derived deliberately by affecting sutural growth using binding and other pressure, as has been practiced in certain cultures of the world (Fig. 26.8).

Congenital anomalies affecting the skull

Hemifacial microsomia (Goldenhar syndrome)

These patients present with unilateral microtia, macrostomia and varying degrees of failure of formation of the mandibular ramus and condyle. Vertebral anomalies and epibulbar dermoids are common. Most cases are sporadic, but familial instances have been described. The facies are strikingly asymmetric as a result of hypoplasia or displacement of the ear. The ear deformities vary from complete aplasia to minor distortions of the pinna, which is displaced anteriorly and inferiorly. Absence of the external auditory meatus is common, as are middle ear deficiencies, which result in conduction deafness. Supernumerary ear tags are present and occur anywhere along a line from the tragus to the angle of the mouth.

IDENTIFICATION FROM THE SKULL

SEX

Generally speaking, the male skull is more robust and the female more gracile, although there are obvious genetic, and therefore racial, variations which must be considered when attempting to assign sex from a skull. The female forehead is generally higher, more vertical and more rounded than the male, and there is a clear retention of the frontal eminences in the female. The male mandible is more robust and larger than that of the female: it generally displays a greater height in the region of the symphysis menti, the chin is more square, the condyles are larger, the muscle attachments are more pronounced and the gonial angle is generally less than 125°. A male skull has thicker and more rounded orbital margins, pronounced supra-orbital ridges, and often a well-defined glabella that occupies the midline above the root of the nose. The temporal lines are more pronounced in the male and the supramastoid crest generally extends posterior to the external auditory meatus.

AGE DETERMINATION

The chronological pattern of dental maturation is well documented and is an extremely important tool for age evaluation. Tooth development can be separated into a number of well defined stages: deciduous mineralization (crown and root), deciduous emergence and maturation, deciduous root resorption, shedding of deciduous teeth, mineralization (crown and root) of permanent dentition, emergence and maturation of deciduous dentition and attrition of permanent crowns (see Ch. 30). These stages do not occur in a linear fashion: while some of the deciduous teeth are emerging, permanent teeth are already being formed. For example, mineralization of the deciduous central incisor commences around the 15th week post fertilization, and this is the first tooth to emerge within the first 5 months after birth. All deciduous teeth are in occlusion by around 3 years of age. The first deciduous teeth to be shed are generally the central and lateral incisors around 7 years of age, when the permanent incisors emerge. The last deciduous tooth to be shed is generally the second molar in the 10th year. The first permanent tooth to show mineralization is the first molar, which occurs around the time of birth (sometimes earlier and sometimes later): it is also the first permanent tooth to emerge at around 6 years of age, and it will reach occlusion by the end of the 7th year. The last permanent tooth to emerge is the third molar: the variability of this occurrence makes it of restricted value for age prediction.

RACE DETERMINATION

The determination of racial or genetic origin is particularly difficult to achieve although it is something that both physical and forensic anthropologists insist on trying to do. The traditional view of race is that it is ‘one of the major zoological subdivisions of mankind, regarded as having a common origin and exhibiting a relatively constant set of physical traits’ (Bamshad & Olson 2003). Classifying groups on this basis is rather restrictive and, in our migrant modern world, somewhat artificial. It is still useful to be able to attempt to assign a ‘most likely’ racial group, especially when dealing with unidentified forensic remains, but there are enormous areas of overlap between the characteristics, and within any racial group there is often a full spectrum of representation. Yet we persist in classification on the basis of visual characteristics, and the area of the body that is most often analysed in this way is the skull.

FACIAL APPROXIMATION (RECONSTRUCTION)

There are fundamentally two approaches to facial reconstruction: (1) Computer reconstruction – the skull is usually scanned by a laser 3-D scanner and an ‘average’ virtual face is wrapped around the skeletal scaffold. This approach is largely automated and requires limited training and expertise. It is rapid to achieve and relatively inexpensive, but relies on a large data set to ensure that the ‘average’ face utilized is appropriate. (2) Modelled reconstruction – the skull is usually cast, and pegs are inserted into the cast at the appropriate tissue depth requirements. In the ‘American’ approach a skin of clay is then moulded over the pegs to approximate the face. In the ‘Manchester’ method each sequential muscle and soft tissue layer is built up around the pegs before a clay skin is moulded over the underlying structures. The modelling approach is clearly more dependent upon experience, takes longer to achieve and is more costly.

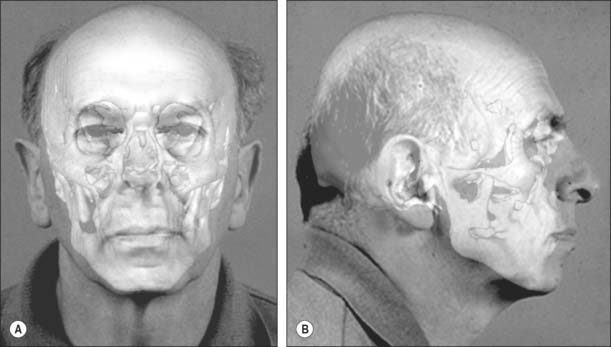

FACIAL SUPERIMPOSITION

Once a possible name has been derived it may be necessary to compare the skull with photographs of the suspected individual. In these circumstances an image of the skull is superimposed onto an image of the face of the missing person (Fig. 26.9). This relies on achieving a live capture image of the skull so that it can be rotated and manipulated into an identical position and to an identical size as the photograph. Features that do not change are lined up: a photograph that shows teeth is ideal because teeth can be lined up with the dentition on the skull. The image of the skull and photograph can then be faded in and out: if this is undertaken at speed, any discrepancies will show up on the image as distortion.

Bamshad M, Olson S. Does race exist? Sci Am. 2003;289:78-85.

Berkovitz BKB, Moxham BJ. Color Atlas of the Skull. London: Mosby-Wolfe, 1994.

Berry AC. Factors affecting the incidence of non-metrical skeletal variants. J Anat. 1975;120:519-535.

Berry AC, Berry RJ. Epigenetic variation in the human cranium. J Anat. 1967;101:361-380.

Bruce V, Burton AM, Hanna E, Healey P, Mason O, Coombes A, Fright R, Linney A. Sex discrimination: how do we tell the difference between male and female faces? Perception. 1993;22:131-152.

Gill GW, Rhine S. Skeletal Attribution of Race: Methods for Forensic Anthropology. New Mexico: Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, 2004.

Ilizarov GA, Ledyaev VI. The replacement of long tubular bone defects by lengthening distraction osteotomy of one of the fragments. Clin Orthopaed Relat Res. 1992;280:7-10.

Lahr MM. The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity: A Study of Cranial Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Lele S, Richtsmeier JT. Euclidean distance matrix analysis: a coordinate-free approach for comparing biological shapes using landmark data. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1991;86:415-427.

Lieberman DE, McCarthy RC. The ontogeny of cranial base angulation in humans and chimpanzees and its implications for reconstructing pharyngeal dimensions. J Hum Evol. 1999;36:487-517.

Lieberman DE, Pearson OM, Mowbray KM. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J Hum Evol. 2000;38:291-315.

Liversidge H. The dentition. In: Scheuer L, Black S. The Juvenile Skeleton. London: Elsevier, 2004.

Maat GJR, Mastwijk RW. Ossification status of the jugular growth plate. An aid for age at death determination. Int J Osteoarch. 1995;5:163-168.

Scheuer L, Black S. Developmental Juvenile Osteology. London: Academic Press, 2000.

Sperber GH. Craniofacial Development, 4th edn. Ontario: BC Decker, 2001.

Vidarsdottir US, O’Higgins P, Stringer C. A geometric morphometric study of regional differences in the ontogeny of the modern human facial skeleton. J Anat. 2002;201:211-229.

Whittaker DK, MacDonald DG. A Colour Atlas of Forensic Dentistry. London: Wolfe, 1989.

Wilkinson C. Forensic Facial Reconstruction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.