Chapter 21 External and Internal Neurolysis

The Peripheral Nerve Operation

Changing Gears

All should understand that the operation will not proceed at a uniform pace. Routine exposures should be completed with dispatch. Outstanding surgeons appear to operate slowly but complete procedures without delay. The secret is that there are no wasted movements. The surgeon is an absolute master of the anatomy. Operations are conducted through fascial planes whose anatomy is clearly comprehended. Muscle is rarely cut. Much is achieved by sharp dissection with a knife, using confident and safe technique; thus the field is relatively bloodless. Trainees should acquire all skills in an appropriate skills laboratory, not the operating room. A trainee who operates in a cell-by-cell manner with excruciating slowness shows clear evidence of a lack of anatomical mastery, and the supervising surgeon should remove such an operator immediately. A trainee who fumbles with the knot of an 8-0 suture under the microscope demonstrates too short a time devoted to skill acquisition in the laboratory

External Neurolysis

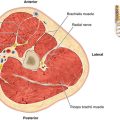

• External neurolysis is the initial step in most peripheral nerve dissections. It consists of freeing the nerve and injury sites from surrounding connective tissues or scar in a 360-degree fashion. It can be done with a scalpel or surgical scissors, without magnification.

• Normal nerve is attached to adjacent longitudinal structures such as the tendons, vessels, fascial planes, and periosteum by a fine, filmy extension of the epineurium called the mesoneurium.

• When healthy, it is fine enough to be transparent. The mesoneurium carries the collateral, more transverse (or sometimes oblique) arteries and veins that relate to the extensive longitudinal vascular system of the nerve. This layer is usually diminished at, as well as above and below, any lesion site.

• Once the nerve is cleared of tissue in a 360-degree fashion proximal and distal to the lesion, one can encircle the nerve with a Penrose drain or, in the case of small nerves, a plastic loop.

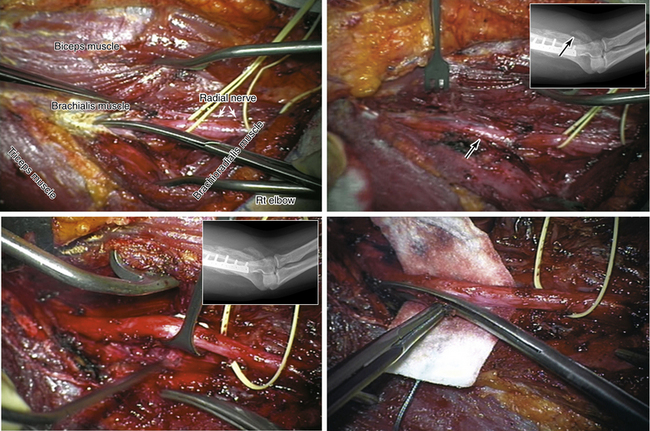

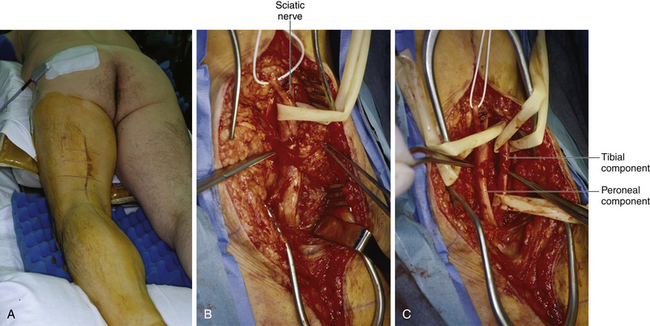

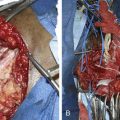

• Then, by gentle retraction, the borders of the nerve lesion, including that on the backside of the surgical field, can be exposed. Gentle traction on adjacent soft tissues with a moist sponge or fine-toothed forceps helps the surgeon dissect a scar away at the injury or lesion site (Figures 21-1 and 21-2).

• It is usually best to establish healthy planes in the nerve both proximal and distal to the lesion. Working from a proximal site to a distal site for this portion of the dissection is most likely to spare branches. For a lesion in continuity, the surgeon becomes a sculptor attempting to restore some form and outline to the overall shape of the nerve.

• Scar is gradually removed by a No. 15 scalpel or fine scissors until some of the nerve itself is displayed (see Figures 21-1 and 21-2). Of course, with badly thickened or neuromatous nerves, this is not possible. Further dissection awaits the outcome of stimulation and recording studies.

• More thorough removal of a scar at an epineurial level may be indicated for a lesion that transmits a NAP and is associated with neuritic pain.

• If the injured nerve is left with only an external neurolysis, it is because it has been determined that repair is either not necessary (because of transmission of NAPs), or not feasible.

Internal Neurolysis

Definition

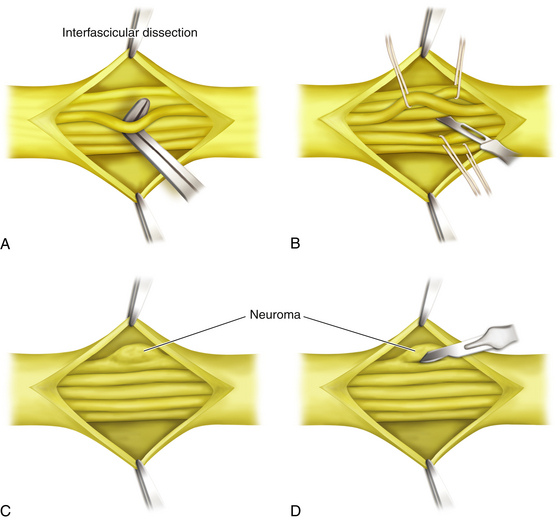

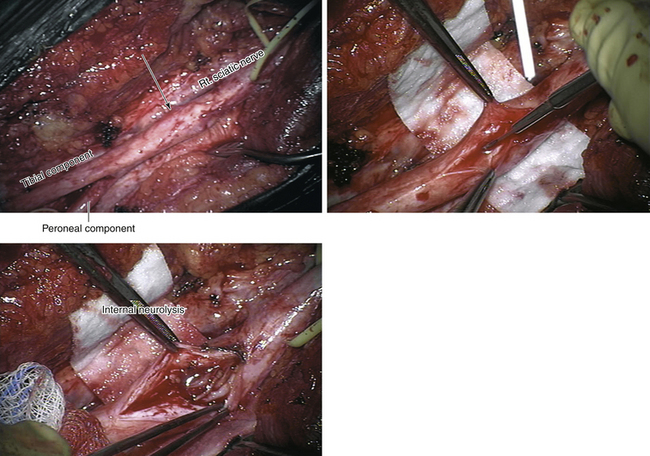

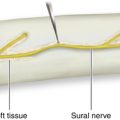

• Internal neurolysis involves an internal dissection of the nerve, splitting it into at least its larger fascicles or sometimes groups of smaller fascicles but maintaining their integrity. Magnification of some sort aids accuracy (Figures 21-3 and 21-4).

• When an injury or a lesion in continuity is present that conducts a NAP and the patient has severe pain, a careful internal neurolysis may be of benefit. There is the risk, however, that such manipulation may further reduce function.

• Another indication for internal neurolysis is a partial nerve lesion, with or without regeneration, as shown by preoperative and intraoperative electrical studies. Under these circumstances, a portion of the cross-section of the nerve may be more involved by injury and a secondary scar than the rest of the nerve.

• The fascicles of the relatively good portion can be split away from the bad portion by a careful internal neurolysis, and both can be evaluated by stimulation and recording studies. The nontransmitting portion can then be resected and repaired, usually by grafts, while the better portion undergoes only a neurolysis. This is a split or partial repair. Such findings and the requisite partial repair suggest a relatively favorable functional outcome for the patient.

Controversies Surrounding Neurolysis

• The value of internal neurolysis when there is no element of neurapraxia and no conduction through a lesion in continuity that is several months old is doubtful.

• Those who believe in the efficacy of such a procedure feel that release of individual fascicles from surrounding scar may reverse a localized conduction block. This may be so in a lesion shown to be neurapraxic by intraoperative recording of NAPs above and below a lesion in continuity but with no conduction across the lesion.

• Another opinion is that internal neurolysis of the complete lesion aids the axonotmetically injured fascicles in regenerating more readily or more completely.

• In our view, if there is no conduction through such fascicles or the whole nerve, and sufficient time has elapsed for recovery, “freeing” or dissecting by internal neurolysis does not provide a very useful function. Under such circumstances, resection and repair may be the better course.

• If a NAP is recorded, yet a portion of the nerve looks badly injured, it is usually better to split the badly injured fascicles away from the more functional ones and to repair them. At the same time, those fascicles that are conducting should be spared resection.