Extensor Brevis Release and Lateral Epicondylectomy

Kelly Akin Kaye, Kristen G. Lowrance and James H. Calandruccio

The pathologic condition of the elbow commonly termed lateral epicondylitis or simply tennis elbow refers to pathologic alterations in the extensor tendon origin(s), which often are solely alterations in the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) tendon. However, this syndrome of lateral elbow pain is rarely accompanied by acute inflammatory cells and hence is now termed lateral epicondylosis. Moreover, many patients who have focal tenderness just distal and anterior to the lateral epicondyle and localized pain in the same region with wrist extension do not play tennis nor related to athletic activity.1

Surgical Indication And Considerations

Etiology

Injury to the extensor tendons at the elbow often can be attributed to repetitive trauma or overuse, leading to mechanical fatigue or biomechanical overload. Some literature reports the possibility of exostosis in the area of the extensor tendons or a degenerative process that causes pain at the lateral epicondyle.2 Symptoms may be described as an ache at the elbow with sharp pain that infrequently radiates to the dorsal forearm and occasionally to the middle and ring fingers with attendant loss of grip.3

The most frequently involved tendon is that originating from the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB). It is responsible for static and dynamic wrist extension required for certain tasks and stabilizes the wrist while grasping. Lesions can occur at the extensor digitorum communis, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digiti minimi, and supinator tendon. According to the current literature, microtraumatic ECRB tendon tears may propagate to include the common extensors.1 Plancher and associates1 report that gross tendon rupture is noted in a large number of patients at the time of surgical intervention.

Microtears can result from repeated sprains, repetitive forceful wrist extension and gripping, and suboptimal mechanics in hitting. Inadequate racquet size or improper tool grip size also can predispose to injury. Other factors that may influence the onset of symptoms are inadequate strength, endurance, and flexibility of the forearm musculature; changes in regular activity; increasing age; and hormonal imbalance in women.3 The incidence is equal in men and women during the fourth and fifth decades, with 75% of all cases involving the dominant arm.1 Among the older population, the insult can possibly be work-related, in contrast to the sports-related injuries seen in the younger population.

Lateral epicondylitis can be successfully managed nonsurgically in 90% of patients with a combination of activity modification, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication, functional and counterforce bracing, various therapeutic modalities, and injection therapy. A small percentage of patients with persistent and disabling symptoms require surgical intervention.4 Lesions caused by overuse during job-related activities are more likely to require surgical intervention secondary to an inability to stop the aggravating activity.

Indications for surgery are individualized according to patient demands and activity level. The period of disability and previous conservative management must be considered before surgical management is chosen. There are no absolute indications for surgical intervention to treat lateral epicondylitis, and the clinician must exercise caution in cases in which secondary gain may be important.

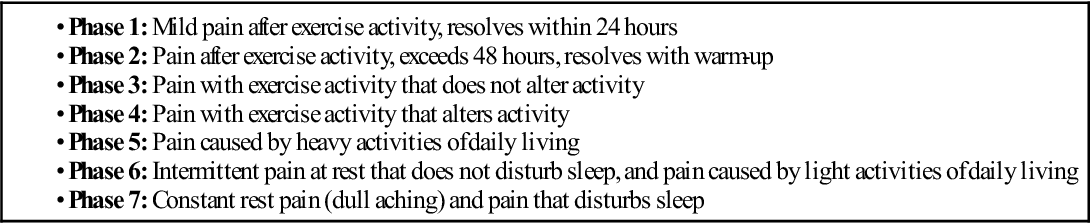

The most important factors in considering surgical intervention are the intensity, frequency, and duration of disability caused by pain. The Nirschl classification system indicating the severity phase of pain, its relation to activity and exercise, and symptom resolution following these activities may have some impact on the therapeutic intervention (Table 8-1). Constant and unrelenting focal lateral elbow discomfort is not tolerated well by active individuals and pain that accompanies exercise and activity (phase 4) may indicate pathologic tendon architectural alteration. Most patients treated surgically have symptoms for 1 year, but special consideration may be given to patients in whom other therapies have failed after 6 months of compliance with a well-tailored therapeutic regimen. Calcification around the lateral aspect of the elbow may portend a less favorable outcome to conservative measures. When symptoms are present for more than 12 months, they will rarely respond to further therapeutic management. Although cortisone injections have been the historical standard for acute pain relief in significant cases of tennis elbow, the high recurrence rate has prompted autologous whole blood, platelet rich plasma, sclerosing agents, botulinum toxin, and periarticular hyaluronate injections to provide more long-lasting results. At this time, despite some compelling reports, no consensus exists regarding the ideal injection for a given patient in a particular phase of their lateral epicondylosis malady.

TABLE 8-1

Nirschl Tendinosis Pain Phases

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Similarly, less invasive surgical interventions are being investigated by some authors for a quicker return to activity and exercise. Arthroscopic treatment when compared with open management may provide athletes a shorter time period to functional recovery. In contrast to percutaneous release, arthroscopic release appears to achieve outcomes more quickly and provide a clearer visualization of the pathology. Nonetheless, the benchmark procedure for this condition is an open release for which various modifications have been proposed. Regardless of the open method chosen, these procedures are technically simple and provide predictable and long-lasting results and rely on readily available instrumentation. No single technique has been or will be adopted by all surgeons.

Surgical Procedure (Modified Nirschl Method)

The common denominator for most lateral epicondylosis procedures, however, is the débridement of the diseased tendinous tissue, most notably the ECRB origin. Hypervascular granulation tissue is characteristically found on the undersurface of the ECRB attachment to the lateral epicondyle and appears on gross inspection as dull, tan-gray, and sometimes gritty degenerative regions. A limited approach commonly incorporated into surgical techniques consists of resection of the diseased section of the tendon and lateral epicondylectomy.

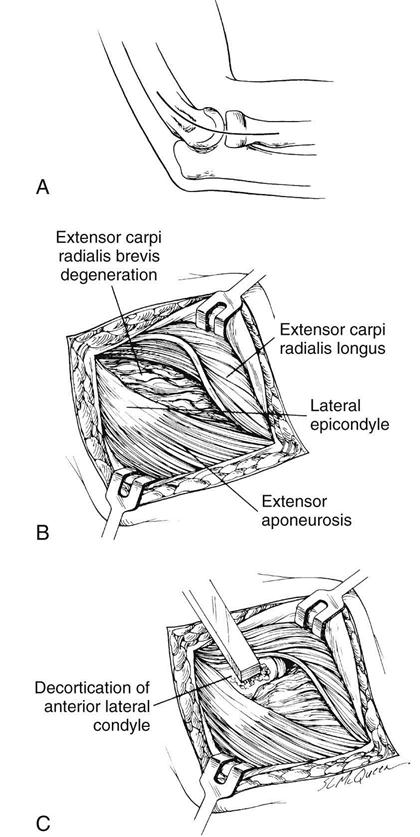

A skin pen is used to outline the intended surgical incision which is 4 to 5 cm long, gently curved, and centered over the lateral epicondyle along the lateral supracondylar ridge proximally and along a line from the lateral epicondyle center toward the Lister tubercle. The skin incision is made under tourniquet control and the skin edges are retracted. Gentle spreading of the subcutaneous tissue is done to protect any cutaneous nerves, often passing through a very superficial bursa over the lateral epicondyle. The extensor fascia is identified through this opening (Fig. 8-1, A). The anterior edge of the ECRB tendon origin is clearly developed by elevating the posterior border of the extensor carpi radialis longus, which at this level is muscular and partially overrides the ECRB origin. The extensor digitorum communis origin may partially obscure the deeper portion of the ECRB (Fig. 8-1, B). The ECRB portion of the conjoined tendon is elevated at the midportion of the lateral epicondyle, distally in line with the forearm axis toward the radiocapitellar joint. The abnormal-appearing ECRB tendon is sharply dissected from the normal-appearing Sharpey fibers. The diseased tissue may appear fibrillated and discolored, and can contain calcium deposits.

Occasionally the disease process also involves the extensor digitorum communis origin. Entrance into the radiocapitellar joint may not be routinely indicated; however, an intraarticular process such as loose bodies, degenerative joint disease, effusion, and synovial thickening on preoperative examination may require a larger incision and arthrotomy for joint exploration.

The lateral 0.5 cm of the lateral epicondyle is decorticated with a rongeur or osteotome, with the surgeon taking care not to damage the articular cartilage or destabilize the joint (Fig. 8-1, C). The ECRB is intimately associated with the annular ligament just proximal to the radial head, thereby limiting distal migration of the ECRB tendon. However, the remaining normal ECRB tendon may be sutured to the fascia or periosteum or attached with nonabsorbable sutures through drill holes in the epicondyle.

The extensor tendon interval is closed with absorbable sutures, with the elbow in full extension to reduce the possibility of an elbow flexion contracture. The skin incision is closed (often with absorbable subcuticular suture material reinforced with adhesive strips) and a soft dressing applied. An arm sling is given for comfort and home range of motion exercises are encouraged before the first office visit in 10 to 14 days postoperative.

Surgical Outcomes

According to Nirschl,5,6 85% of patients were able to return to all previous activities without pain. Pain that occurred during aggressive activities was noted in 12% of the cases observed, and no improvement was apparent in 3% of the cases. When both medial and lateral releases are performed, a high level of patient satisfaction was achieved in a group of 53 patients followed an average of 11.7 years, and 96% of patients returned to their sports activity. Reasons for failure include misdiagnosis or the concomitant diagnosis of entrapment of the posterior interosseous nerve, intraarticular disorders, or lateral elbow instability. Poor prognostic factors include poor initial response to cortisone injections, numerous previous cortisone injections, bilateral lateral epicondylitis, other concomitant associated disorders, and smoking.

Therapy Guidelines For Rehabilitation

Phase I

TIME: 1 to 14 days after surgery

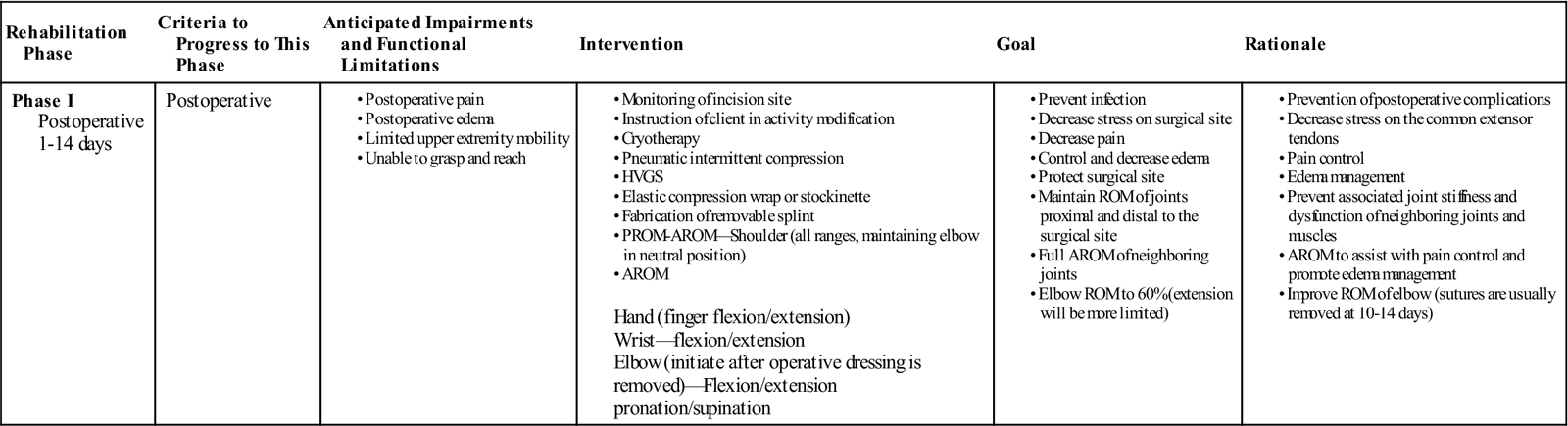

GOALS: Achieve full range of motion (ROM) of adjacent joints, promote wound healing, control edema and pain, and increase active range of motion (AROM) of the elbow (Table 8-2)

TABLE 8-2

Extensor Brevis Release and Lateral Epicondylectomy

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I Postoperative 1-14 days |

Postoperative |

Hand (finger flexion/extension) |

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

After surgery, the therapist instructs the patient concerning the need to elevate the site to avoid edema and initiates gentle AROM exercises for the hand and shoulder. The patient is to remain immobilized in the postoperative splint with the elbow positioned at 90°. On the fifth day after surgery, the postsurgical dressing and splint are removed and therapy is initiated to the elbow.

The initial postoperative examination is conducted by a physical or occupational therapist. Upon removal of the postsurgical dressing, the examination conducted should measure and address ROM, edema, pain, functional ability, and wound healing. ROM of the hand, wrist, elbow, and shoulder along with girth measurements of the hand, forearm, elbow, and upper arm are taken. Pain levels can be monitored using a 0 to 10 VAS (Visual Analog Scale). It is recommended to have patients use this during therapy sessions and with the home exercise program for optimum accuracy. Functional ability can be monitored using the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand) or PRTEE (patient-rated tennis elbow evaluation) questionnaire. The above recorded data should be taken at subsequent visits for comparison and assessment of the patient’s progress.

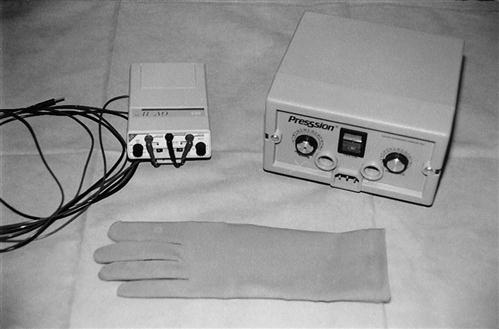

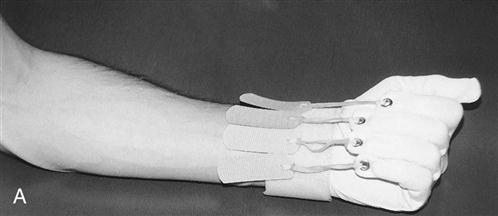

In this phase the patient’s wounds are kept clean and dry until the sutures are removed 10 to 14 days after surgery. After the operative site has been exposed, other forms of edema control can be used, including ice, pneumatic intermittent compression (performed at a 3 : 1 on/off ratio at a pressure of 50 mm Hg), and high-voltage galvanic stimulation (HVGS). The recommended settings for the use of HVGS to prevent edema are negative polarity with continuous modulation at 100 intrapulse microseconds and intensity to the sensory level.7 The patient also can be fitted with a light elastic compression wrap or stockinette (such as Coban or Tubigrip) to wear intermittently throughout the day and at night for continued edema control at home (Fig. 8-2). AROM exercises also are initiated for the elbow, forearm, and wrist after the postoperative dressing is removed.8 ![]() Passive ROM (PROM) and joint mobilization of the elbow and forearm are contraindicated at this time.

Passive ROM (PROM) and joint mobilization of the elbow and forearm are contraindicated at this time.

Some surgeons prefer to keep the elbow immobilized in a removable posterior elbow splint until the second week after surgery. This splint is typically fabricated from a low-temperature plastic with the elbow positioned at 90°; it is worn between exercise sessions and at night (Fig. 8-3).

Pain can be managed using HVGS at the same settings as those used for edema control; the physician also may prescribe oral medications.

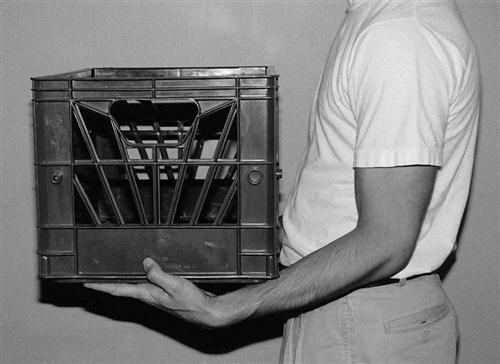

The first postoperative visit is a good time to begin patient education regarding activity modification and proper mechanics during work- and sports-related activities. ![]() Patients should be educated to avoid forceful static grip, repetitive and static wrist extension, and resistive supination, which are commonly seen with use of hand tools such as screwdrivers, and pliers, and with keyboarding. Patients should also be advised to avoid the overhanded lifting technique.

Patients should be educated to avoid forceful static grip, repetitive and static wrist extension, and resistive supination, which are commonly seen with use of hand tools such as screwdrivers, and pliers, and with keyboarding. Patients should also be advised to avoid the overhanded lifting technique.

The primary mode of lifting should be a bilateral underhanded or neutral forearm approach (Fig. 8-4).

During this initial phase, the therapist should closely monitor the patient’s reports of pain and tolerance to ROM exercises, noting any sympathetic changes that may lead to a complex pain syndrome. Signs and symptoms to be noted are as follows:

Phase II

TIME: 15 days to 4 to 5 weeks after surgery

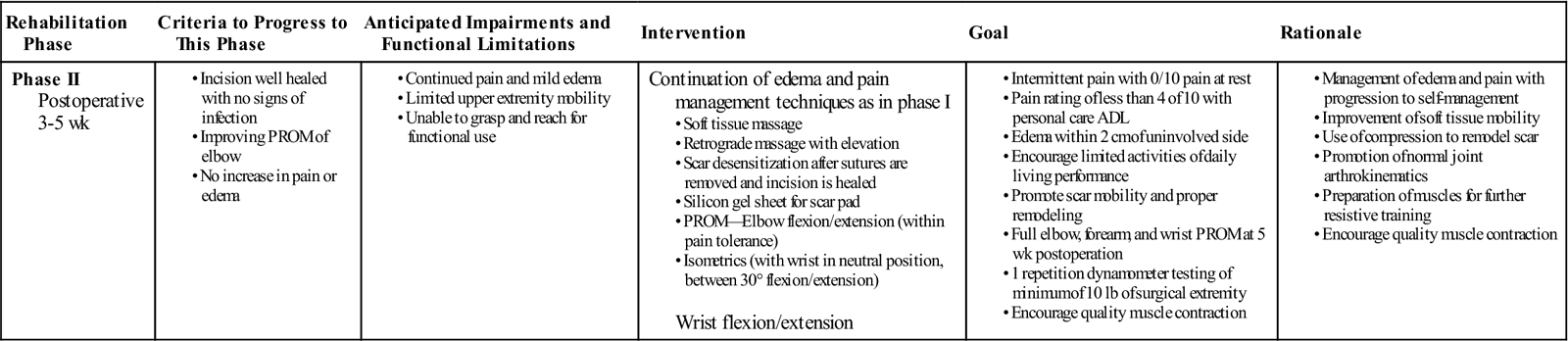

GOALS: Control edema and pain, achieve full elbow PROM, maintain full ROM of adjacent joints, and promote mobility of the scar tissue (Table 8-3)

TABLE 8-3

Extensor Brevis Release and Lateral Epicondylectomy

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase II Postoperative 3-5 wk |

Continuation of edema and pain management techniques as in phase I Wrist flexion/extension |

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

ADL, Activities of daily living; PROM, passive range of motion.

After the immobilization phase, the therapist should initiate gentle AROM exercises for the patient’s elbow three to four times each day.9 During the first ROM phase, the therapist should emphasize the importance of complying with the home exercise program and attending the regular therapy sessions.

ROM exercises to be included are as follows:

![]() The patient should avoid positions that place maximal stress on the common extensor tendons such as elbow extension with extreme wrist flexion (Fig. 8-5).3 To prevent reinjury, progressive resistive exercises also should be avoided at this time. Sports-related activities to avoid include tennis, golf, lacrosse, or forceful throwing of a ball.

The patient should avoid positions that place maximal stress on the common extensor tendons such as elbow extension with extreme wrist flexion (Fig. 8-5).3 To prevent reinjury, progressive resistive exercises also should be avoided at this time. Sports-related activities to avoid include tennis, golf, lacrosse, or forceful throwing of a ball.

Stanley and Tribuzi3 recommend isometric exercises with the wrist in a neutral position or at no more than 30° of extension or flexion in preparation for further resistive training. ![]() Exercises should be performed three to four times daily with 15 to 20 repetitions being sufficient. Isometrics should be performed with submaximal effort only.

Exercises should be performed three to four times daily with 15 to 20 repetitions being sufficient. Isometrics should be performed with submaximal effort only.

As ROM progresses, the therapist should carefully monitor the patient’s edema. The management of edema is specific to the patient and only one technique may be required. The following technique can be used for mild edema:

Moderate edema is treated with the following:

After the sutures are removed and the incision has healed appropriately, scar management is needed.

This includes both desensitization and scar remodeling. Because hypersensitivity can limit functional use, desensitization should begin during the patient’s first therapy session after suture removal.9 Scar remodeling consists of using massage (when appropriate) to help maintain mobility of the scar by freeing restrictive fibrous bands, increasing circulation, and allowing the pressure to flatten and smooth the scar site (Fig. 8-6).9 The therapist also may consider using a silicone gel sheet or other silicone-based putty mix as a pad over the scar to assist in remodeling.

The therapist should instruct the patient to rub the sensitive area for 2 to 5 minutes three to four times daily with textures such as fur, yarn, rice, Styrofoam, or corn. Other useful textures include towels, clothing, dry beans, and rice.9

Patients will be limited to lifting no more than 10 lb after surgery. On grip strength testing, patients typically demonstrate a 50% deficit when the operative hand is compared with the nonoperative one.

Phase III

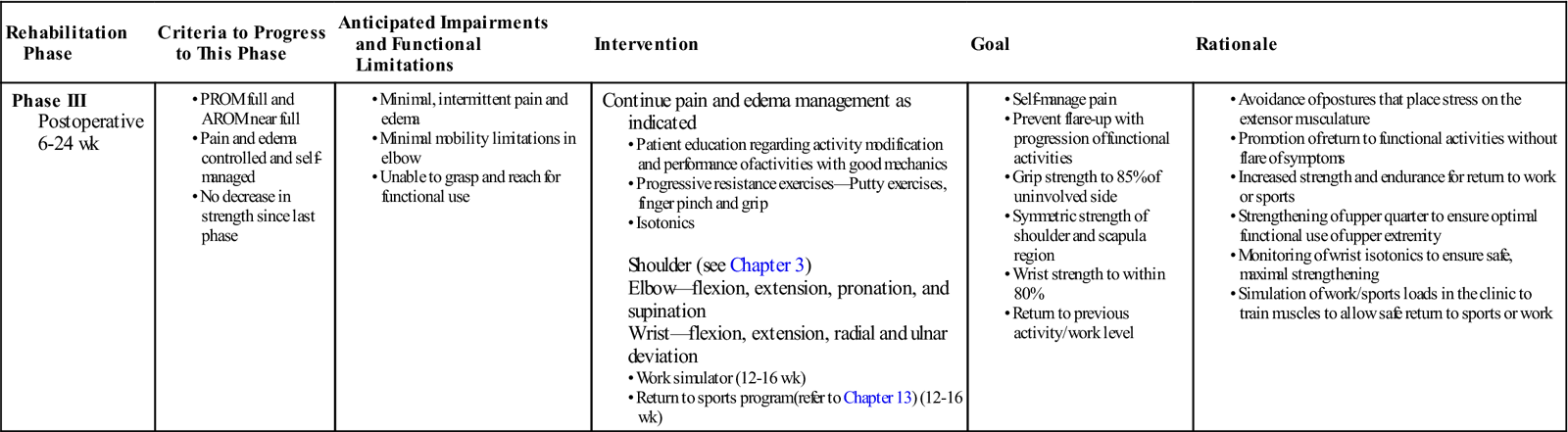

TIME: Between 4 to 6 weeks to 6 months after surgery

GOALS: Control pain, maintain full elbow and forearm ROM, strengthen upper extremity, and regain normal forearm flexibility (Table 8-4)

TABLE 8-4

Extensor Brevis Release and Lateral Epicondylectomy

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III Postoperative 6-24 wk |

Continue pain and edema management as indicated

Shoulder (see Chapter 3)Elbow—flexion, extension, pronation, and supination Wrist—flexion, extension, radial and ulnar deviation • Return to sports program (refer to Chapter 13) (12-16 wk)

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

AROM, Active range of motion; PROM, passive range of motion.

Between 4 to 6 weeks after surgery, the therapist should initiate a progressive strengthening program.9 At this point in the rehabilitative process the patient should have full ROM of the hand, wrist, and elbow, and the focus should be on building strength and training for endurance with the goal of returning the patient to work or sports.

The goal of the strengthening program is to promote conditioning of the entire upper extremity, particularly the forearm, to prevent reinjury caused by overstretching or overloading. To ensure that maximal strengthening is achieved, eccentric exercises are recommended for the extrinsic forearm muscles.3 At this time it is appropriate to initiate extrinsic forearm stretching.

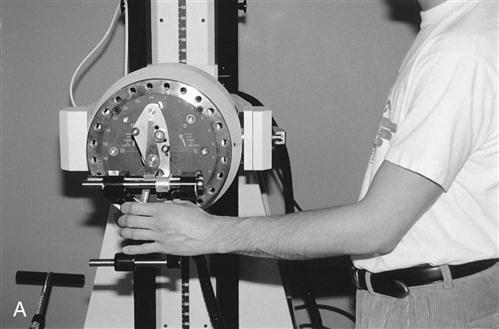

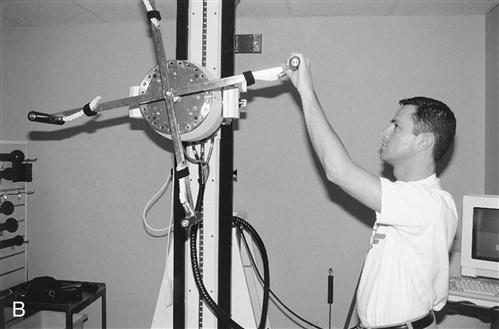

Each patient’s conditioning program is formulated according to activity tolerance, previous activity level, and requirements for return to work or sports. If the patient can perform active exercises without pain, he or she is well enough to begin resistive and light work or sports-related activities using free weights and a work stimulator such as Baltimore Therapeutic Equipment (BTE) or Lido (Fig. 8-7). The key is to continue educating the patient and training her or him to lift with the forearm in a neutral position and avoid postures that stress the extensor muscles.

The components of the program are as follows:

Normally a return to activity can be anticipated by the fourth month after surgery.8

Troubleshooting

Problems encountered after a lateral epicondylectomy include pain, recurrence of symptoms, edema, inadequate ROM or stiffness, and scar expansion.

Increase in Pain Level or Recurrence of Symptoms

The therapist should carefully monitor the patient’s pain level throughout the rehabilitation process. The Magill pain questionnaire can aid in monitoring changes in levels or characteristics of pain. Exercise progression should occur based on the patient’s reports of pain. In some cases of severe pain, the physician may prescribe a transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) unit. If the pain persists or occurs at the end of the rehabilitative process, the therapist may consider the use of a counterforce brace to allow the patient to return to the previous level of activity.

Persistent Edema

Edema control involves ice, elevation, HVGS, pulsed ultrasound, compression wraps, retrograde massage, and lymphatic massage. Continuous passive motion machines have been used intermittently throughout the day and at night with some success to reduce edema. Decreasing the activity level or suspending the use of resistive exercises also may be necessary.

Inadequate ROM or Stiffness in Adjacent Areas

The most common mobility problem involves loss of full elbow extension. By 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, the therapist can talk to the surgeon about using static progressive or dynamic splints to improve extension. Static splinting is achieved by using custom-made, low-temperature plastic material molded to the patient at the end ROM and adjusted weekly. Dynamic splints are available commercially. For hand and finger stiffness, use of a flexion glove or composite flexion stretching with a Coban or elastic (Ace) wrap is usually successful (Fig. 8-8).

Painful Scar

If the scar management techniques detailed earlier do not produce the desired result, additional methods include the following:

Circumferential desensitization using fluidotherapy also may be considered.

Clinical Case Review

1 Marvin is a 50-year-old diabetic who had extensor brevis release and lateral epicondylectomy 14 days ago. His sutures were removed, and he was taken out of the postoperative splint 2 days ago. He has full shoulder, forearm, and hand mobility with elbow AROM of 45° to 110°. His pain remains 3 or 4 out of 10 even at rest, and moderate edema is localized to the elbow and proximal one third of the forearm. His incision shows mild dehiscence with small amounts of exudate. What is appropriate intervention for his continued pain, edema, and suspicious wound?

The therapist should begin by ruling out infection. The patient’s basal and elbow surface temperatures should be assessed, and he should be checked for redness or streaking near the elbow and forearm. If the patient shows no temperature or color change and exudate is clear, Steri-Strips should be applied to the incision and the patient’s physician should be contacted. Once infection is ruled out, the following should be done: edema control using retrograde massage (avoiding the area of incision), HVGS and elevation (or both), PROM, and A/AROM to the elbow for flexion and extension. Scar remodeling should be delayed until the incision is well closed.

2 Cindy is a 60-year-old housewife who had arthroscopic release of her right tennis elbow 3 weeks ago. She is now complaining about right shoulder pain. She does not remember any injury to her elbow; she wears her arm sling for comfort during the day. On examination, her active and passive motion of the right shoulder is painful and somewhat limited. What should be added to her therapy program, and what instructions should she be given?

Cindy has developed an early adhesive capsulitis of her shoulder and should be instructed to stop wearing her arm sling. She should also be started on a shoulder program to work on her ROM. This could begin with Codman exercises and a PROM program followed by AROM and strengthening.

3 Jim is 34 years old. Approximately 7 weeks ago he had an extensor brevis release and lateral epicondylectomy performed. He is anxious to recover quickly so he can play softball on the weekends. Mild resisted exercises were initiated 1 week ago, and Jim is performing them at home. His pain level has noticeably increased over the past 4 days. However, he can control the pain with ice and antiinflammatory medication. Should Jim’s exercise program be altered? If so, how should it be altered?

Jim is aggravating his symptoms with the exercises. He also may be doing the home exercises too aggressively. The primary goal should be to alleviate pain and swelling. After pain and swelling are under control, gradual strengthening can be initiated in small doses with more rest periods than before. Treatment soreness should be minimal and controllable with the administration of ice packs. The amount of exercise and resistance should be gradually increased.

4 Janet is a 35-year-old accountant. She had extensor brevis releases and a lateral epicondylectomy after various attempts at conservative treatment failed. At 7 weeks after surgery, Janet’s elbow extension ROM is 15°. What type of treatment may be effective at this stage for increasing her elbow extension?

The patient should be placed in a dynamic splint or in a static progressive splint at night to gain full extension.

5 Matt is a 47-year-old business executive. He underwent an extensor brevis release with lateral epicondylectomy 4 weeks ago. Initial wound healing was good; however, he returned to frequent travel with his job. He now returns to therapy complaining of increased pain at rest reported as an 8/10, and swelling in the entire forearm and hand. He experiences shooting pains and describes a burning sensation in the involved upper extremity. Upon inspection, he has global swelling in the forearm with mottled appearance of skin and fusiform swelling around the finger joints. Range of motion has decreased in the elbow, wrist, and hand and he is unable to fully fist. Would it be appropriate to progress this patient to phase II treatment? What should your treatment consist of this treatment session?

At week 4 postoperation, a patient should have increasing range of motion and a decrease in pain. The above symptoms can indicate complex regional pain syndrome. This treatment session should consist of modalities to decrease pain and edema. No progression to the next phase in exercise regime should be made at this session. A referral back to the physician is indicated.

6 Sharon is a 45-year-old woman. She works as a computer programmer and had extensor brevis release and lateral epicondylectomy 14 weeks ago. She is performing a home exercise program of progressive resistive exercises and intrinsic stretches for the forearm and elbow four times a week and has returned to work full time. She now complains of pain at the end of the day, with mildly noticeable swelling at the lateral elbow. She attends therapy once a week. What should the therapist evaluate at this week’s appointment? What are the right recommendations?

The therapist should assess the patient’s grip strength and forearm, elbow, and shoulder girdle strength as compared with the uninvolved side and previous weeks’ values. Elbow mobility and edema (via palpation girth measurements) should also be checked. The patient should be asked to fill out a pain questionnaire or visual analog scale for pain. If strength values show a decrease of 10% or are less than 85% of the uninvolved side, the patient might have returned to work too early. If strength values are within desired limits but the patient shows significant edema and increased pain, she should be encouraged to decrease the weight with progressive resistive exercises and begin using ice packs for 10 to 15 minutes at the end of her work day. Stretching technique should be reviewed to make sure that the patient is not overstretching, as well as proper mechanics and activity modification while at work. The patient should be asked to wear a counterforce brace while at work (for up to 6 months after surgery).

7 Ben is a 38-year-old superintendent for a commercial construction company. He is 16 weeks past his surgery and was released from therapy 4 weeks ago with a recommendation for a functional capacity evaluation. He returns to the clinic for his 1-month reassessment. Against physician’s orders, he returned to work stating that he did not do any heavy lifting with his job. He reports difficulty using his tools and soreness in the forearm when using tools with vibration. He also states that approximately midway through his day, he feels weak in the surgical hand. Upon reassessment, Ben demonstrates only 50% grip strength as compared with the nonsurgical extremity. Range of motion continues to be within normal limits. Resistive testing and palpation is negative for pain. What can be done to address his complaints?

Ben should benefit from wearing an antivibratory glove and padding tools that are used repetitively. Consultation with the surgeon regarding further rehabilitation based on his functional capacity evaluation in a work hardening setting is also indicated to increase grip and upper extremity strength and endurance required for this patient’s job.

8 Madeleine is a 40-year-old veterinarian who is 4 to 5 weeks postoperation. She presents with complaints of numbness and tingling along the small and ring fingers of the affected extremity. She still has mild pain rated as 3/10 and mild edema localized to the surgical site but is tolerating passive and active range of motion and isometric exercises well since the removal of the 90° elbow splint. She has full shoulder, forearm, and hand mobility with elbow AROM of 10° to 130°. Further questioning reveals that her preferred sleeping position is side-lying with her arms tucked under her pillow. What are the right recommendations for this patient?

Madeleine has developed an ulnar neuritis likely because of her sleeping position. She should be instructed to wear her elbow splint at night only to prevent her from sustained hyperflexion during sleep and to protect the ulnar nerve. She should progress to the phase II treatment plan as indicated.

9 Nash is a 33-year-old basketball coach who is 6 weeks postsurgery. He has full range of motion of the elbow, a mobile scar, and is tolerating self-care/activities of daily living without pain. He has not yet progressed to resistive training in his home exercise program but is doing well and seems to be ready to progress to phase III. During a therapy session, he reveals that he has been teaching/demonstrating dribbling skills to his little league team on the weekends. Should his exercise program be altered?

Nash needs to be educated regarding the time frame of the healing process after surgery. He should be reminded that at this time, full pain-free range of motion is the main goal and at this time participation in any sport or repetitive activity is prohibited. His lifting restriction continues to be 10 lb or less.

10 Ross is a 48-year-old professional race car driver. He is now 18 to 20 weeks postsurgery. He has full range of motion, equal grip strength bilaterally, and MMT of involved upper extremity of 5/5. He tolerates a 45-minute exercise session of the work simulator without residual pain. He is now ready to return to competitive driving. What guidelines would he be given for returning to racing?

Patient should be released to return to racing per physician’s okay. He should be advised to allow for adequate rest periods between race practice sessions and to watch for return of symptoms, such as soreness, aching, or weakness. He can use ice to the elbow after driving as needed.

11 Tucker is a 21-year-old college football quarterback. During the off season he had a modified Nirschl procedure for lateral epicondylitis. He is now 12 weeks after surgery. He has full active and passive range of motion, is tolerating resistive strengthening exercises without reproduction of symptoms, and reports 0/10 pain at rest. He states he has only mild soreness in the elbow the day after he works out. During his leisure time he decided to go camping and presents to the clinic with a large pocket of swelling near his olecranon. What should be the next treatment?

This patient could possibly have an olecranon bursitis brought on by an infection from an insect bite. He needs to be referred back to his surgeon for possible aspiration and medication as indicated.

12 Elizabeth is a 55-year-old medical transcriptionist who had an open extensor brevis release 7 weeks ago. All goals for phase II have been met (see Table 8-3). What are appropriate guidelines for the following exercise components? Grip strength; sustained grip; forearm and wrist strength; upper arm strengthening.

Grip strengthening with light resistive putty two to three times daily for 2 minute sessions. Sustained grip with a 1-lb weight with light resistive putty for 2 minutes. Forearm and wrist PRE’s with No. 1 weight, 1 to 3 sets of 10 repetitions. Upper arm strengthening varies with general health, age, sex, and lifestyle/activity level.