49 Expressive dysphasia

Salient features

Examination

• Assess the patient’s ability to find appropriate words, whether comprehension is intact (e.g. asking the patient to name geometric shapes, parts of the body, or components of common objects such as a pen).

• Repetition may or may not be intact.

• Proceed by telling the examiner that you would like to carry out a neurological examination of the patient for a right-sided stroke.

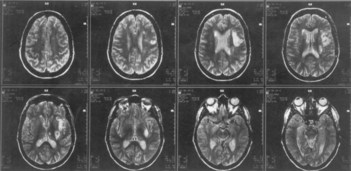

Remember: The neurologic basis of language is controlled by a network of neocortical areas centered in the perisylvian regions of the left hemisphere of the brain. This language network is almost always located in the left hemisphere of the brain and includes the perisylvian portions of the inferior frontal and temporoparietal regions, known as Broca’s and Wernicke’s (p. 205) areas, respectively, as well as surrounding regions of the frontal, parietal and temporal cortex. The term dysphasia denotes a disorder in language processing caused by damage to this network.

Diagnosis

This patient has expressive dysphasia (lesion) caused by a right-sided stroke (aetiology).

Questions

Advanced level questions

What do you understand by stuttering?

• Stuttering is a disorder of fluency of speech fluency characterized by the involuntary repetition or prolongation of sounds, syllables, words or phrases, as well as frequent pauses, impeding the rhythmic flow of speech.

• Onset is typically between 3 and 6 years of age, and ~ 5% of preschool children may stutter. The majority of young children who stutter go on to make a full recovery. The disorder may continue unabated in some, resulting in a prevalence of about 1% among adults.

What do you know about genetics of speech?

• Linkage studies of prevalent types of speech and language disorders have implicated several regions of the genome, most notably on chromosomes 3, 13, 16 and 19. The putative risk genes underlying these linkages have yet to be identified.

• Mutation in FOXP2, which is located in chromosomal band 7q31 and encodes a transcription factor, has been described in a British family with autosomal dominant transmission of oral motor and speech dyspraxia. These patients have problems sequencing the precise movements of tongue, lips, jaw and palate that contribute to intelligible speech (known as verbal dyspraxia or childhood apraxia of speech). They also have difficulties with learning and production of non-speech sequences involving the orofacial musculature (orofacial dyspraxia) and have a broad profile of linguistic deficits in expressive and receptive domains—problems that affect both oral and written language. The protein product, FOXP2, downregulates the expression of CNTNAP2, a gene that encodes a neurexin protein. The general relevance of CNTNAP2 to speech dyspraxia remains to be determined. CNTNAP2 is probably associated with disorders associated with nonsense-word repetition (e.g. autism).

• Genes at 7q11.23 are exquisitely sensitive to dosage alterations, which can influence human language and visuospatial capabilities.

• Genetic factors have been implicated in stuttering, with linkage to markers on chromosome 12 and variations in genes governing lysosomal metabolism (N Engl J Med 2010;362:677–85).