Exposure of the Carotid Bifurcation

Introduction

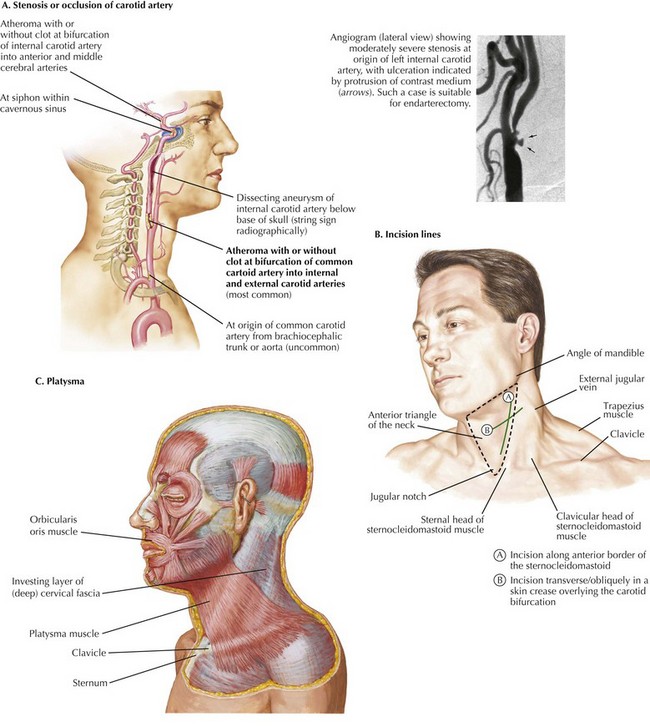

Carotid endarterectomy is one of the most frequently performed vascular operations. The vast majority of these procedures are for atherosclerosis at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, which lies within the anterior triangle of the neck, usually at the upper border of the thyroid cartilage (Fig. 32-1, A). The key anatomic boundaries are the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the midline, and the mandible (Fig. 32-1, B).

Carotid Endarterectomy

The procedure begins with proper positioning of the patient, with the neck extended and turned toward the opposite side. The incision can be made along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) or transversely (obliquely) in a skin crease overlying the carotid bifurcation (Fig. 32-1, B). The bifurcation can easily be located with duplex ultrasound. The platysma muscle is then divided, exposing the deep cervical fascia (Fig. 32-1, C).

Surgical Principles

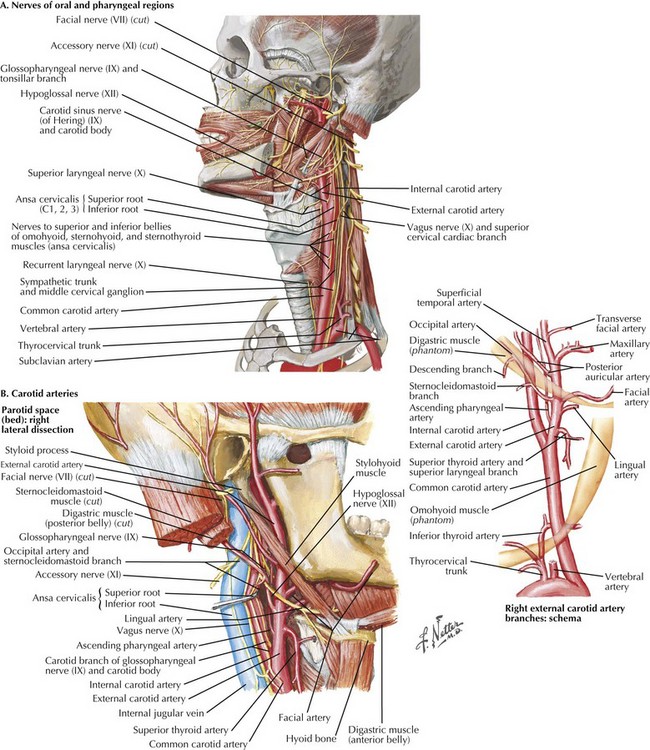

The external jugular vein and greater auricular nerve lie in this plane; the vein can be ligated, but the nerve must be preserved to avoid numbness of the ear lobe (Fig. 32-2, A).

Next, two key steps are necessary to expose the carotid bifurcation. The first is mobilization of the anterior border of the SCM, which is invested within two layers of the deep cervical fascia (Fig. 32-2, B). If a transversely oriented incision is used, this requires creation of subplatysmal flaps, both cephalad and caudad, on the plane of the anterior SCM fascial layer.

Anatomic Landmarks

The ansa cervicalis nerve (also known as ansa hypoglossi) is often seen running along the anterior surface of the common carotid artery (Fig. 32-2, A). This nerve can be divided with impunity, and the cranial end followed to its junction with the hypoglossal nerve. The hypoglossal nerve runs between the internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery and is usually found about 2 cm above the carotid bifurcation. However, its position can vary. Often, small jugular venous tributaries drain the SCM at this level, along with accompanying arteries that must be divided. Extreme care must be taken to avoid bleeding in this location; attempts to control bleeding are a common cause of injury to the hypoglossal nerve.

Arterial Dissection

The internal carotid artery is mobilized next. This procedure often requires division and mobilization of an adipose and lymphatic mass that contains small venous tributaries of the internal jugular vein and their accompanying arteries. These vessels, especially the sternocleidomastoid branch of the occipital artery, tether the hypoglossal nerve and may need to be divided to mobilize it. Although tiny, these vessels can cause troublesome bleeding, and careful dissection is required to identify and ligate them. The internal carotid artery lies immediately deep to this layer, as does the hypoglossal nerve. Mobilization of the hypoglossal nerve anteriorly enables more distal exposure of the internal carotid artery to the level of the diagastic muscle (Fig. 32-3).

Carotid Bifurcation

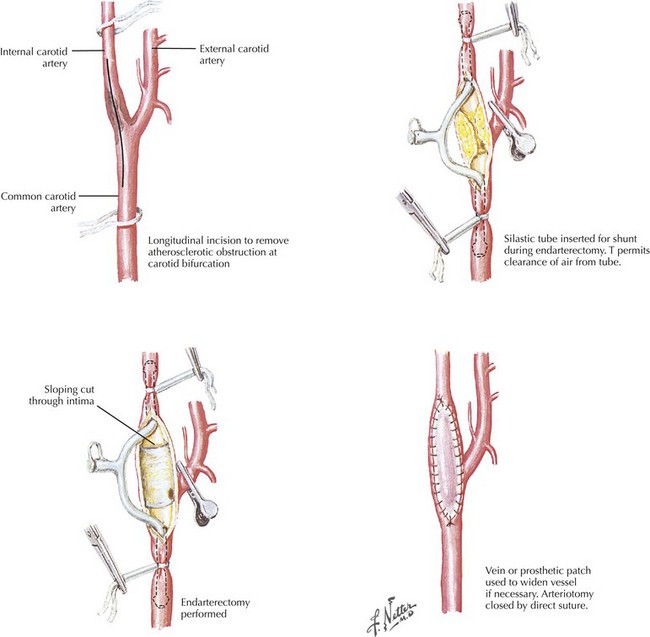

Extremely gentle dissection of the bifurcation is important to prevent dislodgement and downstream embolization of material from underlying artherosclerotic plaque. When completed, this dissection should permit gentle lifting of the vessels toward the surface of the wound and greatly ease shunt insertion when necessary (Fig. 32-4).

Arteriotomy and Closure

After completion of the endarterectomy and achieving hemostasis, closure is straightforward. The deep cervical fascia does not need to be closed, although many surgeons choose to do so. The platysma layer should be reapproximated, followed by the skin. If necessary, drains should be placed within the carotid sheath and brought out through a separate site posterior and inferior to the incision (Fig. 32-4).

Lord, RSA, Raj, TB, Staryl, DL, et al. Comparison of saphenous vein patch, polytetrafluoroethylene patch and direct arteriotomy closure after carotid endarterectomy: postoperative result. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:521–529.

Roseborough, GS, Perler, BA. Carotid artery disease: endarterectomy. In: Cronenwett J, Johnston KW, eds. Rutherford’s vascular surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010:1443–1468.

Zarins, CK, Gewertz, BL. Carotid artery surgery. In: Atlas of vascular surgery, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.