Chapter 87 Expedition Medicine

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

Historical Background

The desire for exploration runs deep in the human spirit. “The Journey” appears as a recurring theme in historical, religious, and literary records of numerous societies. It is used as a vehicle to describe and understand the mystery of human existence: the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and their wandering in the wilderness for 40 years, recorded in the Pentateuch books of the Old Testament; Homer’s Odyssey, describing the journey of Odysseus home from the Trojan Wars; and the voyage of Marlow along an African river in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The Oxford English Dictionary defines an expedition as “a journey undertaken by a group of people with a particular purpose, especially that of exploration, research or war.”54

A history of expeditions is beyond the scope of this chapter. Readers are referred to excellent works published on this topic.1,18 The first clearly documented expeditions are those of Harkhuf, who was the governor of Upper Egypt during the 23rd century BC and whose three explorations along the Nile are recorded on his tomb at Aswan. In modern times, the golden age of expeditions and exploration stretches from the middle of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, although it has been mentioned that many of those who occupy a prominent place in the Western imagination were merely recorders of preexisting civilizations, rather than genuine explorers of untrodden ground.1 Despite this observation, many expeditions that took place during this period illustrate both the varied environments and eternal controversies that surrounded expeditions then and continue to do so today:

Expedition Demographics

In the six decades since Hillary and Tenzing stood on the summit of Mt Everest, the demographics of expeditions, and mountaineering expeditions to the Great Ranges in particular, have changed dramatically. Although audacious, groundbreaking ascents continue to be made,11,22 mountains that were once the domain of only an elite group of climbers, who served long apprenticeships to gain the skills necessary to survive in hostile surroundings, are today frequently attempted by less experienced mountaineers. Where once expedition members were chosen for their experience and ability to function autonomously, many now buy into the infrastructure of a commercial expedition and purchase the services of highly experienced guides to fulfill their summit dreams. There has also been an explosion in charity treks over the last 15 years, which has contributed to large numbers of unfit wilderness- and altitude-naive individuals being led into an environment for which they are totally unprepared.

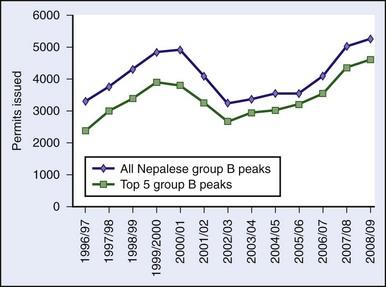

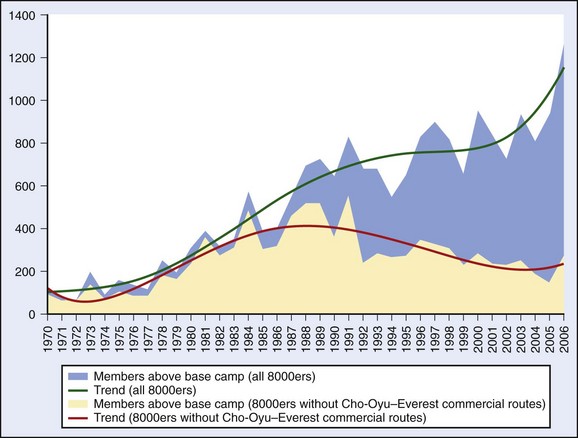

Many accounts from leaders, guides, physicians, and a growing number of books recount expeditions in the commercial era in an unfavorable light.* Figure 87-1, online, from the Himalayan Database, shows climbing activity on all of the 8000-m (26,247-foot) peaks between the years 1970 and 2006, with the commercial routes on Mt Everest and Mt Cho Oyu separated out. This demonstrates the large increase in the number of people attempting these routes. The increased popularity of the highest peaks has been mirrored on lower peaks and by nonclimbing trekkers. Figure 87-2 illustrates the numbers of climbers with permits issued for the 18 Nepalese group B climbing peaks, which includes the most popular peaks below 7000 m (22,966 feet), formerly known as trekking peaks, between 1996 and 2009. The number of visitors to Sagarmatha National Park of Nepal has increased massively over the last 35 years. Between 1972 and 1973 there were approximately 1400 visitors; 7492 persons visited in 1989 and 25,925 in 2001. Visitor numbers fell during the recent civil unrest but were reported at over 20,000 in 2004.57

Recently many countries have seen development of the charity trek business, in which supporters of charities attempt endurance events such as treks, long-distance cycle rides, or summit climbs to raise money through individual sponsorship of these efforts. These have been further popularized by widely publicized “celebrity” treks” that make light of the risks.42,40 Inexperienced participants entirely depend for their safety on the advice, guidance, and care provided by the trek organizers.

Three very popular destinations are Mt Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Mt Everest Base Camp in Nepal, and Mt Aconcagua in South America. Mt Kilimanjaro at 5895 m (19,341 feet) attracts more than 20,000 climbers per year, of which fewer than 70% reach the summit. Between 1996 and 2003, 25 tourists died attempting to reach the summit.28 Sensible ascent profiles of Mt Kilimanjaro would suggest that trekkers require 7 to 9 days above 2500 m (8202 feet) to ascend safely and maximize their chances of summit success. In one comparative study of commercial charity treks, it was found that 15 out of 20 treks planned only 4 nights above 2500 m (8202 feet).52,37 There are many reasons for this. The Tanzanian government levies a charge in excess of $100 per day for each day tourists spend in the national park, and as a result, in an attempt to maximize profits, trekkers are encouraged to climb the mountain as quickly as possible, thereby putting lives at risk. None of the charity groups surveyed offered the option of an acclimatization ascent of Mt Meru (4566 m [14,980 feet]) before attempting Kilimanjaro.

Tourists may choose to ignore sensible ascent profiles, but this is not the case for their employed porters, without whom they would be unable to make an attempt on the mountain. No formal statistics are available, but porters die as a result of altitude illness or when guides push on in bad weather.43 The difficulties faced by mountain porters are discussed in more detail later.

Preexisting Medical Conditions

More participants with complex medical problems are attempting expeditions. There is once again need for international data. The medical advisor to a major British commercial expedition company has described his experience of clients who successfully completed mountaineering trips with Hodgkin’s lymphoma; epilepsy; insulin-dependent diabetes; a cardiac pacemaker; postcoronary angioplasty, or postrenal transplant.34 It is increasingly common for prospective clients to have a history of depression, anxiety, hypertension, asthma, or diabetes.35 Comparatively little is known about the effects of altitude on the majority of common medical problems.26 Most published recommendations deal with cardiopulmonary pathologic conditions at altitude but are frequently based on theoretic considerations rather than documented experience.10,33,46,51,55 The result of this lack of documented experience with preexisting medical conditions is that advice given to potential expedition participants may be unduly conservative and prohibitive. It is apparent that, with appropriate motivation, care, and planning, it is possible for people with significant comorbidities to successfully and safely trek and climb in remote, hostile wilderness environments.34 The approach to pre-expedition screening is discussed later.

The Expedition Medical Officer

Clinical Skills

Expedition Phase

The EMO needs to have broad-based clinical skills. As in nonexpedition clinical practice, it is usual for the EMO to have a specialist interest, such as tropical medicine, envenomation, or high-altitude medicine. However, other than for the situation of the high-altitude environment, this is unlikely to provide the majority of the expedition medical caseload, which will generally consist of common, usually minor, ailments, of which the most frequent will be gastrointestinal illnesses, followed by minor orthopedic and trauma problems, respiratory conditions, and other minor medical and surgical problems.3,13,56 The required clinical skills of the EMO will also be influenced by the following:

Expedition Skills

Personal Skills

Communication Skills

Good communication skills are crucial to effectively eliciting a patient’s problems and concerns. This includes communicating information and discussing treatment options and providing psychological and emotional support.47 These communication skills are not only useful while practicing medicine, but also when working as an arbitrator in times of team conflict. This is discussed in greater detail later.

Skills of Conflict Resolution

There will be times of increased stress or pressure. The pressure has the potential to spill into professional conflict. Much that has been written on the art of conflict resolution27 can probably be summarized in one word—communication. The EMO might be in the position of arbitrator during times of expedition conflict. The key to avoiding nearly all issues of conflict is to first examine and resolve them during the expedition planning stage and second, not to shy away from discussing them. Clear dialogue should highlight and resolve any issues in the following three categories:

Decision Making and Hierarchy

Conflict Stemming From Expedition Purpose, Ethics, and Morals

Ethical considerations transcend every part of an expedition, from the expedition purpose or goal, through delivery of care to expedition members and affiliates, to the impact on host cultures and countries. The four principles of ethical debate and behavior6 that can be appropriately applied to the individuals and expedition as a whole2 are the following:

Who is Qualified to be the Expedition Medical Officer?

The first EMOs were physicians who frequently combined providing medical care with their role as climbers or with physiologic or other scientific research.* Skills and knowledge were generally passed on to aspiring EMOs in an informal manner. With the growth of commercial expeditions, many physicians with little or no experience or understanding of expedition medicine accepted the offer of a reduced-price place on an expedition. This provided the pretense of medical cover to the group, sometimes with disastrous consequences. There is no doubt that the EMO does not necessarily need to be a physician. Emergency medical care on expeditions has been provided safely by registered nurses or paramedics with appropriate training and experience similar to civilian and military prehospital care. There is no information as to how care provided by a nonphysician EMO compares with that provided by a physician; however, UK emergency nurse practitioners have demonstrated equally competent levels of skill and knowledge when compared with their traditionally trained medical colleagues.5,58 No established medical specialty encompasses all of the skills and knowledge required for the safe practice of expedition medicine.

Increasingly, expeditions do not have a formal EMO, so the pre-expedition and postexpedition and expedition phases are performed by different people. The pre-expedition medical screening and planning and the provision of training and medical kits may be provided by a corporate (company) EMO, whereas care in the field is delivered by the expedition leader or guide. Nonmedical veterans of many expeditions may be more experienced than the EMO, so, along with appropriately trained expedition leaders, they can provide a high standard of emergency care to expedition members. Box 87-1 gives an example of the lifesaving care provided by an expedition leader to a Nepalese porter during an expedition to Baruntse. The role of telemedicine in providing expert medical support to expeditions without an EMO and the legal responsibility of non–medically qualified leaders providing medical care to members of their group are discussed later. One unique model of care is the Everest Base Camp Medical Clinic (Everest ER), founded in 2003 by Dr. Luanne Freer to address the problems of expeditions on Mt Everest. The temporary clinic offers medical care to all expeditions on the Nepalese side of Mt Everest during the spring climbing season.17,21

BOX 87-1

A Nepali Porter With Severe HACE and HAPE

HACE, High-altitude cerebral edema; HAPE, high-altitude pulmonary edema; IM, intramuscularly.

From Paul Donovan, expedition leader with Jagged Globe.

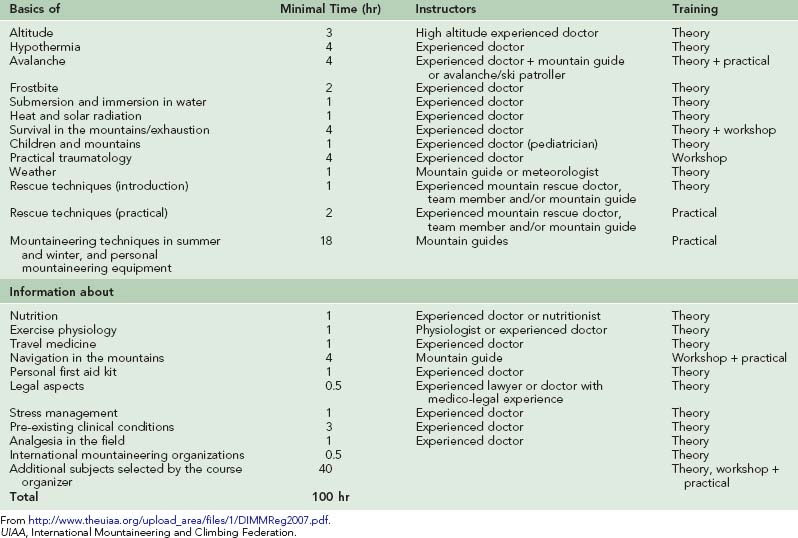

Paralleling the explosion in commercial expeditions and increased formalization of all aspects of medical training are the many courses around the world offering wilderness, expedition, or mountain medical training in one form or other. In August 1997, the medical commissions of the International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA), International Committee on Alpine Rescue (ICAR), and International Society for Mountain Medicine (ISMM) established minimal requirements for courses in mountain medicine. These standards, last updated in 2007, have been adopted across many countries. There are currently six UIAA-ICAR-ISMM approved diplomas in mountain medicine in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.53 With the growing concern about possible litigation from expedition clients (see Legal and Ethical Considerations of Expedition Medicine, later), it seems advisable that there be consensus among expedition medical providers about the core knowledge and clinical competencies required to practice expedition medicine in each of its major environments. Details of the UIAA-ICAR-ISMM syllabus for the Diploma in Mountain Medicine are given in Table 87-1.

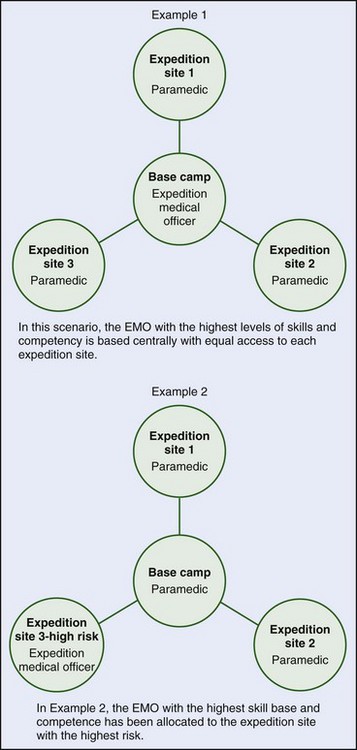

Satellite expeditions medically coordinated from a single central base camp allow utilization of broader skill sets and abilities, with the most qualified or experienced medic able to provide advice or support from a central location (Figure 87-3, online). There are numerous variations based on this theme. These might include having the senior EMO based with the group deemed at highest medical risk, with outpost medical support provided from that location.

Expedition Medical Planning

The EMO should aim to prevent illness and injury and to treat those who sustain injuries or become unwell as quickly and appropriately as possible. The chance of successfully achieving these aims is greatly increased by careful pre-expedition planning, which should include medical screening of all expedition members and risk assessment and management. Any serious illness or injury will fully occupy the EMO and his or her work will be greatly facilitated if other team members have received pre-expedition medical training. An expedition medical planning checklist is given in Box 87-2.

BOX 87-2 Expedition Medical Planning Checklist

Anticipate and plan evacuation of a severely ill or injured person from each part of the expedition.

Anticipate and plan evacuation of a severely ill or injured person from each part of the expedition.Medical Screening

All participants should complete a detailed health questionnaire (Box 87-3). The information may prompt a request for further details from the patient, the family physician, or specialist. It is important to determine the severity of the condition and whether the disease is stable, worsening, or improving. One useful predictor of future performance is the individual’s prior ability to cope with wilderness travel in other isolated or remote areas. The individual may need to be involved in the final decision and take into consideration expedition duration and environment, presence of medical support, field communications, and remoteness of the location and evacuation options.

BOX 87-3 Health Questionnaire for Preexisting Medical Conditions

Risk Management

Potential risks to expedition members should be systematically identified and control measures instituted to reduce these risks.4 This easily neglected exercise is an important part of expedition planning. The EMO should work closely with the expedition leader to formulate a formal risk assessment (Box 87-4). All team members must be fully informed before departure of the risks to which they are likely to be exposed and the means of hazard control and must understand that it is not possible to eliminate all risk completely (Box 87-5). With this information, they can make an informed decision about their participation in the expedition.

BOX 87-5 Briefing the Expedition Team

The most serious risks while traveling are falls and other injuries; drowning; road traffic collisions; altitude illness and heatstroke; serious infections (malaria, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]); and homicide.4 Although not exhaustive, the following list highlights the environment-specific hazards and risks that should be systematically evaluated during risk assessment:

Hazards Common to Most Expedition Environments

| Solar radiation | Sunburn |

| High or low ambient temperatures | Heat and cold injuries |

| Hot, dry environments | Dehydration and heat exhaustion |

| Poor water and food quality | Gastrointestinal illnesses |

| Isolation | Unfavorable psychological reactions |

| Overcrowding | Upper respiratory and other infections |

| Attitudes and behavior | Sexually transmitted infections, injuries |

Wildlife Hazards

| Dogs | Infected bite wounds and rabies |

| Leeches | Wound infections |

| Snakes | Envenomation |

| Ticks | Typhus and other tick-borne diseases |

| Hippopotami | Animal attacks, capsizing of boats |

| Parasites | Infestations |

| Bears | Multiple injuries |

Local Conditions

| Lack of shelter | Hypothermia |

| Dangerous roads | Road traffic collisions |

| Open fires and stoves | Burns and scalds |

| Endemic diseases | Malaria, schistosomiasis, dengue fever, encephalitis |

| Human factors | Assault, kidnapping, terrorism, conflict |

Environment-Specific Hazards

High Altitude

| Altitude | Altitude-related illness (acute mountain sickness [AMS], high-altitude cerebral edema [HACE], high-altitude pulmonary edema [HAPE], altitude-related cough) |

| Solar radiation | Sunburn and ultraviolet (UV) keratitis (snowblindness) |

| Cold | Hypothermia and tissue cold injury |

| Avalanche and rockfall | Traumatic injury |

| Blizzard | Getting lost |

| Lightning | Lightning injuries |

| Climbing | Falls and traumatic injury |

| Snow holing | Carbon monoxide poisoning |

| Asphyxiation |

Desert

| Solar radiation and extreme heat | Sunburn and heat illnesses |

| Lack of water | Collapse, dehydration |

| Snakes and scorpions | Envenomation |

Expedition Medical Training

When operating in wilderness areas, it is common to provide medical care in remote hostile environmental conditions. The EMO will usually carry out his or her role independently with finite medical supplies, sometimes with limited communications and unreliable casualty evacuation facilities. Patient evacuation may be delayed for many reasons. When the EMO is required to look after more than one patient or casualty, his or her resources will be stretched to the limit. It is therefore important that expedition team members be trained to give first and second aid. The exact nature of the medical training for expeditions to wilderness areas should be tailored to suit the environment. For example, it may need to include training in tropical illnesses, malaria, cold injury, and high-altitude illness. Many of these subjects are not covered in “standard” first-aid courses. Advanced techniques that should be taught include the use of prescription medications, the use of specialized rescue equipment, and the reduction of fractures and dislocations.12 All team members should have undergone basic first-aid training. Essential topics for all who operate in wilderness areas are the following:

There is no clear consensus in the United States regarding “industry standards” for wilderness first aid.68 In the United Kingdom, British Standard 8848 was established in April 2007. This simply states: “The venture provider shall check the first aid qualifications of the leadership team and ensure that they are commensurate with the needs of the venture”9 Boxes 87-6 and 87-7 list common expedition complaints and recommended training courses for wilderness first aid.

Expedition Medical Kit Preparation

It is not possible to prepare for every possible eventuality and there is always a balance between being underprepared and having too much in a kit.39 For detailed recommendations regarding medical kit contents, see Appendix A.

Medical Kit Packaging

In general, liquid medicines are best avoided because of weight and bulk. Tablets should be in blister packs to protect from damage during transport. Glass ampules are less robust than are plastic ampules; both need to be protected from extremes of cold and heat. For insulin, snakebite serum, and other medications that must be kept cold, specialized pouches are available, for example, those produced by Frio (http://www.friouk.com). Food vacuum flasks have been used to protect items from desert heat and Arctic cold.

Problems of Transporting Controlled Drugs

Morphine and other controlled drugs should be taken on overseas expeditions only if done under strict supervision. Some countries impose stringent laws,25 including the death penalty, for possession of opiates. In the United Kingdom, a Home Office license is required to export controlled drugs, but this does not protect the individual from applicable laws in other countries.24 If controlled drugs are dispensed, this should be recorded in a controlled-drugs register.

A valuable source of information on the carriage of medications can be found through the International Narcotics Control Board.41 Information is heavily weighted toward narcotics control, and the website contains information only for countries willing to submit data. Nevertheless, it is a valuable resource for the EMO. The EMO should pay specific caution to any medications that affect the central nervous system, any that can be abused (such as steroids), injectables, and increased quantities of medication. The medical kit and medication should be accompanied by an official letter detailing its intended use, for whom it is intended, and the prescribing authority. This should be signed by the prescriber, with an official stamp, and, where possible, the needed language translations.

Emergency Equipment

Depending on the expedition, the EMO may consider emergency airway management equipment, including the laryngeal mask airway, oxygen, and chest drainage apparatus. For persons operating in areas where they may encounter ballistic trauma, QuikClot and the combat application tourniquet (C-A-T) may be required for the treatment of torrential hemorrhage. It is important to base the decision to take such equipment on a realistic assessment of the likelihood of a safe and rapid evacuation of any casualty requiring such interventions. Many different emergency splints are available, but many orthopedic injuries can be immobilized with improvised splinting (see Chapter 27).

Base Camp and Satellite Medical Kits

A comprehensive medical kit should be kept at base camp.24 Satellite camps should have smaller kits tailored to the size of the group, medical training of the team members, and likelihood of serious illness or injury. In addition, each team member should carry personal medication, with some spares (Box 87-8). For more prolonged expeditions or remote field stations, mechanisms must be in place to resupply the medical kits.

Medical Kits for Special Environments

The same basic medical kit can be used in many different theaters of operation; however, modifications will be required, depending upon the activities and environment:59

Communications Technology

BOX 87-9 Radio Procedure

Box 87-10 outlines the story of a British climber who sustained frostbitten toes on Mt Aconcagua and avoided amputation through consultation with the UK Frostbite Advice Service. This service has been in existence since 2005 and has helped nearly 40 climbers with a combination of remote service advice, often using digital imaging, and rapid follow-up consultation on return to the United Kingdom. Contact details for both Ifremmont and the UK Frostbite Advice Service are given in the Resources section at the end of this chapter.

Legal and Ethical Considerations of Expedition Medicine

Duty of Care

Each person has a duty of care to not injure others; however, this duty is different in certain circumstances. Leaders or members of a group have a clear duty of care to the other members of their group. Moral and ethical duties may exist to rescue another person but must be distinguished from legal duties. Common law does not impose a legal duty on an individual to rescue another person; however, a legal duty may be imposed on certain people in certain circumstances. A physician is under a legal duty to render emergency care to his or her own patient, although professional bodies such as the UK General Medical Council expect physicians to provide emergency assistance even when off duty: “In an emergency, wherever it may arise, you must offer anyone at risk the assistance you could reasonably be expected to provide.”23 Whether a physician is treating a patient, advising a patient, or advising an expedition company, a clear duty of care exists in law. All who provide medical care or advice, be they physicians, nurses, paramedics, or laypersons, must do so reasonably and carefully.

Comparison with Peers

The courts will compare the provided standard of care with that expected from a person with similar experience and training acting in the same or similar circumstances. In effect from April 2007, British Standard 8848 describes recommended safety standards for expeditions and other adventure travel.68

Standard of Care

In UK law, the case of Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) produced the following definition of what is reasonable: “The test is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill at the risk of being found negligent. It is sufficient if he exercises the skill of an ordinary man exercising that particular art.” This definition is supported and clarified by the case of Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority (1993).8

Confidentiality

All persons who are ill or injured must be confident that sensitive medical information will be kept confidential. For example, such information will not be made known to the rest of the expedition team or other individuals who are not directly involved in medical treatment or nursing care. However, in the United Kingdom, the General Medical Council has made it clear that physicians also have a duty to the public at large. Rare circumstances can arise where confidentiality needs to be broken so that the health and safety of other expedition members are not jeopardized. The expedition leader may need to be informed that an individual is concealing an illness or refusing treatment. Box 87-11 gives an example of a situation where a patient’s withholding information about his past medical history engendered significant consequences for himself and the expedition.

How Much Should Laypersons Be Taught About Medicine?

Lay people should be taught sufficiently to enable any expedition to be safe insofar as that can be achieved. There exists a duty of care to exercise skills consistent with training, experience, and procedures. The duty of care will obviously vary. Care rendered by a completely untrained Good Samaritan providing urgent assistance in extreme or remote circumstances can easily be distinguished from the setting of a simple bony fracture by a trained first-aider acting at the direction of medical personnel providing advice by telephone or radio. The duty of care is defined in each individual circumstance.16

Liability on Commercial Expeditions

Medical indemnity is discussed in detail later (see Professional Indemnity Insurance). Most medical indemnity organizations provide Good Samaritan coverage for physicians acting in any part of the world. The British Medical Defence Union (MDU) defines a Good Samaritan act as “The provision of clinical services related to a clinical emergency, accident or disaster when you are not present in your professional capacity but as a bystander,” and states that “MDU members who have a current Professional Indemnity Policy are covered for claims arising from Good Samaritan acts anywhere in the world.”50 However, in an expedition setting, this would apply only where a team member just happens to be a physician. It would certainly not cover a physician receiving any form of inducement (for example, a discount in the trip fee or sponsorship in kind) that implies the physician has an official medical role on the expedition.

Expeditions Departing Without an EMO

Medical Records

Brief, accurate, and contemporaneous medical records should be made for all clinical encounters. In serious illness or injury, this is essential so that detailed clinical information can be given to those who deliver definitive care to the patient. This principle applies to both medical and nonmedical expedition staff providing medical care—Box 87-1 is an example of excellent record keeping by a nonmedical expedition leader. Whenever a patient is evacuated or referred to a formal medical facility, he or she should be accompanied by clear notes outlining the history and treatment. If there are later concerns about the standards of care given in a wilderness setting, superb clinical notes will help to defend actions if legal activities occur. Examples of suitable medical records for use in the field can be found at http://medex.org.uk/diploma/resources.php.

Professional Indemnity Insurance

Professional indemnity insurance is an increasingly contentious issue and with considerable international variation. In the United Kingdom, professional indemnity insurance is provided by four national organizations: the Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland; the MDU, the Medical Protection Society, and the Royal College of Nursing. Each organization generally provides discretionary indemnity to its members for a period of volunteer or charity work such as accompanying an expedition or trek or being based in a mountain or wilderness clinic. Importantly, “This is dependent on the doctor confirming he or she is suitably trained and equipped to undertake that work,” (MDU personal communication).50 There are, however, a number of countries in which indemnity insurance is not available. These include the United States and Canada and their dependent territories. Work for which the physician receives financial remuneration will be considered for indemnity cover but is likely to be charged on a pro rata basis of up to $6500 per year as of April 2010. In the United States, medical professional liability insurance is provided by private insurance companies at considerable cost. Any American EMO would need to discuss indemnity with his or her insurance company on an individual basis.

Nurses and paramedics acting as EMOs should inform their respective professional indemnity carriers about the potential extended scope of practice. The scope of professional indemnity insurance provided varies among national professional bodies. In the United Kingdom nurses are assumed to work within a skill set commensurate with their level of knowledge and training and in the event of a claim would be held accountable for straying from a suitable level of competency.65

Ethical Considerations of Interacting with Local Populations

During the Expedition

During the expedition walk-in, it is important to visit local health care facilities and to meet the staff. Such visits can provide encouragement for the local staff and inspiration for the visiting EMO, because the work carried out in such posts, often with minimal resources, is frequently impressive. It offers the opportunity to discuss with the local staff the best ways in which the expedition should interact with the community. It is also useful to discuss the existence of any indigenous healers in the area and to be guided by the local health staff as to the best way in which to interact with them (Box 87-12). The visit should also be used to determine the best ways to evacuate sick expedition members should direct air evacuation not be available.

BOX 87-12 Interacting With Local Healers

The left hand of a young Sherpa boy (Figure 87-4) who presented to the Community Action Nepal–International Porter Protection Group Rescue Post at Machermo in the Gokyo Valley of Nepal with a gangrenous accessory digit. His mother had been advised by a local shaman to tie a piece of the child’s hair around the accessory digit. The boy was referred to the Hillary Trust Hospital at Khunde, where he underwent amputation of the digit under ketamine anesthesia without complications.

Treating Local Staff

Although the extent to which expeditions should treat members of local populations is open to debate, the manner in which local staff working for the expedition should be treated is not. They should receive the same medical care as do other members of the expedition. George Finch,20 a member of the 1922 Mt Everest expedition wrote at the time:

Sadly, this self-evident sentiment is not the experience of many local staff who are regularly required to work without adequate clothing or shelter and too frequently abandoned and left to fend for themselves when they fall ill. This abuse of local staff, and in particular portering staff, is one of the most shameful features of modern expeditions.48,49 Box 87-13 tells the typical story of a sick porter abandoned by his expedition. Box 87-14 gives a Nepalese porter’s perspective of his work.

BOX 87-13 Another Nepalese Porter With HAPE and HACE

HACE, High-altitude cerebral edema; HAPE, high-altitude pulmonary edema.

The International Porter Protection Group offers the following guidelines for the care of local staff:64

Biomedical Research

There is a long-standing tradition of physiologic and medical research on expeditions, particularly at high altitude, where such work has made a major contribution to understanding cardiorespiratory physiology at sea level as well as at altitude.69 It is crucial that any research on human subjects during an expedition meet the same ethical criteria as if it were carried out at home, namely:

Dealing with the Media

Because of the inherent nature of expeditions, serious accidents, injury, and deaths can occur. On such occasions, it may fall to the EMO to talk to the media. This can be a very stressful experience. The manner in which such incidents are reported can have a significant effect on the public’s and the legal profession’s long-term interpretation of events. Box 87-15 gives guidelines on the best ways in which to interact with journalists and reporters.

BOX 87-15 The Media-Savvy Mountain Medic

APPENDIX A Recommended Medical Kit

| ANTIMICROBIALS | ||

| Ceftriaxone powder for injection | 4 g | 5 ampules |

| Chloramphenicol 1% ointment | 4 g | 3 tubes |

| Clarithromycin | 250 mg | 40 tablets |

| Ciprofloxacin | 500 mg | 50 tablets |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 250/125 mg | 84 tablets |

| Doxycycline | 100 mg | 80 tablets |

| Mebendazole | 100 mg | 20 tablets |

| Metronidazole | 400 mg | 100 tablets |

| Metronidazole suppositories | 1 g | 10 suppositories |

| Quinine sulfate | 200 mg | 50 tablets |

| Rabies vaccine | 1 mL | 5 vials |

| PAINKILLERS, LOCAL ANESTHETICS/SEDATIVES | ||

| Aspirin | 325 mg | 32 tablets |

| Bupivacaine 0.25% for injection | 10 mL | 5 vials |

| Acetaminophen/codeine | 30/300 mg | 80 tablets |

| Diclofenac | 50 mg | 100 tablets |

| Ibuprofen | 400 mg | 80 tablets |

| Ketamine solution for injection | 2 vials | |

| Ketorolac solution for injection | 30 mg/mL | 5 vials |

| Lidocaine 1% for injection | 5 mL | 10 ampules |

| Lidocaine 2% gel | 30 mL | 2 tubes |

| Lorazepam solution for injection | 2 mg/mL | 5 vials |

| Midazolam solution for injection | 1 mg/mL | 5 vials |

| Acetaminophen | 500 mg | 100 tablets |

| Tetracaine 0.5% eye drops | 15 mL | 6 bottles |

| Tramadol | 50 mg | 20 tablets |

| Eszopiclone | 7.5 mg | 20 tablets |

| GASTROINTESTINAL | ||

| Bisacodyl | 5 mg | 20 tablets |

| Antacid tablets | 100 tablets | |

| Oral rehydration solution sachets | 100 sachets | |

| Loperamide | 2 mg | 50 capsules |

| Prochlorperazine | 5 mg | 56 tablets |

| Ranitidine | 150 mg | 60 tablets |

| Prochlorperazine solution for injection | 5 mg/mL | 5 vials |

| Prochlorperazine suppositories | 25 mg | 10 suppositories |

| CARDIOVASCULAR | ||

| Bisoprolol | 2.5 mg | 20 tablets |

| Atropine solution for injection | 1 mg/mL | 5 vials |

| Enoxaparin | 80 mg/0.8 mL | 10 prefilled syringes |

| Nitroglycerin sublingual spray | 400 mcg/spray | 1 bottle |

| RESPIRATORY/ALLERGY | ||

| Epinephrine 1 : 1000 solution for injection | 1 mL | 10 ampules |

| Beclometasone for inhalation | 80 mcg | 2 canisters |

| Chlorphenamine | 4 mg | 60 tablets |

| Chlorphenamine solution for injection (UK) | 10 mg/mL | 5 vials |

| Diphenhydramine solution for injection (U.S.) | 25-50 mg | |

| Hydrocortisone powder for injection | 100 mg/2 mL | 5 vials |

| Prednisone | 5 mg | 100 tablets |

| Albuterol for inhalation | 90 mcg | 2 canisters |

| ALTITUDE | ||

| Acetazolamide | 250 mg | 250 tablets |

| Dexamethasone | 2 mg | 40 tablets |

| Nifedipine | 20 mg | 20 capsules |

| Portable altitude chamber | 1 | |

| OTHER MEDICATIONs | ||

| Multivitamins with minerals | 500 tablets | |

| Dimenhydrinate | 50 mg | 40 tablets |

| CREAMS AND OINTMENTS | ||

| Acyclovir cream | 2 g | 6 tubes |

| Hemorrhoidal cream | 1 tube | |

| Mupirocin cream | 15 g | 6 tubes |

| Topical steroid/antibiotic ear drops | 10 mL | 4 bottles |

| Clotrimazole cream | 20 g | 6 tubes |

| Aqueous cream | 50 g | 1 tube |

| Fluconazole | 150 mg | 4 tablets |

| Hydrocortisone 1% cream | 15 g | 6 tubes |

| Sunblock SPF 25+ | 4 tubes | |

| DRESSINGS | ||

| Adhesive plasters | 50 assorted | |

| Alcohol swabs | 100 | 2 boxes |

| Cotton wool | 4 packets | |

| Crepe bandages | 7.5 cm | 4 units |

| Dressing No. 15 | 2 units | |

| Eye dressing No. 16 | 4 units | |

| Fluorescein eye test strips | 10 strips | |

| Gauze swabs | 5 × 5 cm | 100 swabs |

| Nonadherent dressing | 10 cm2 | 5 dressings |

| Nonadherent dressing | 5 × 5 cm2 | 5 dressings |

| Hypoallergenic tape | 2.5 cm | 2 rolls |

| Adhesive strips, assorted | 4 packets | |

| Triangular bandages | 8 bandages | |

| Petrolatum gauze | 10 cm2 | 10 rolls |

| Zinc oxide roll plaster | 2 rolls | |

| INJECTION EQUIPMENT AND INTRAVENOUS (IV) FLUIDS | ||

| 2-mL, 5-mL, 10-mL syringes | 20 of each | |

| Blue, green, orange needles | 20 of each | |

| IV cannulae, 14 gauge, 18 gauge | 10 of each | |

| Giving sets | 5 units | |

| Normal saline | 1 L | 6 bottles |

| Gelofusine | 500 mL | 8 bottles |

| Dextrose 5% | 500 mL | 4 bottles |

| AIRWAY CARE | ||

| Oropharyngeal airways (sizes 2, 3, 4) | 2 of each | |

| No. 6 nasopharyngeal airway | 2 units | |

| Bag-valve-mask device | 1 unit | |

| Minitracheostomy set | 1 unit | |

| Endotracheal tubes 7, 9 mm | 2 of each | |

| Laryngeal mask airway sizes 3,4 | 2 of each | |

| Catheter mounts for above | 2 units | |

| Laryngoscope | 1 unit | |

| Oxygen tubing | 1 unit | |

| Oxygen cylinder | 1 unit | |

| Handheld suction unit | 1 unit | |

| MAJOR TRAUMA | ||

| Latex gloves (nonsterile) | 100 pair | |

| Tuff cut scissors | 1 unit | |

| Chest drain 32 Fr | 2 units | |

| Heimlich valve | 2 units | |

| Kendrick Traction Device | 1 unit | |

| SAM Splint | 2 units | |

| Adjustable cervical collar (Stifneck Select) | 2 units | |

| Urinary catheter 14 Fr | 2 units | |

| Catheter bag and tubing | 2 units | |

| Bladder syringe 50 mL | 2 units | |

| Nasogastric tube 12 Fr | 2 units | |

| Disposable scalpels | 2 units | |

| Gloves sterile (medium) | 10 pair | |

| Sutures: | ||

| 2/0 silk straight | 4 units | |

| 4/0 nonabsorbable suture | 5 units | |

| 5/0 nonabsorbable suture | 5 units | |

| Staples and remover | 1 unit | |

| Needle holder | 1 unit | |

| Toothed forceps | 1 unit | |

| Scissors | 1 unit | |

| Spencer Wells forceps | 2 units | |

| Tissue glue | 5 units | |

| Dental first-aid kit | 1 unit | |

| Low-reading thermometer | 1 unit | |

| Thermometer (digital) | 1 unit | |

| EXAMINATION | ||

| Pen flashlight | 3 units | |

| Stethoscope | 1 unit | |

| Aneroid sphygmomanometer | 1 unit | |

| Ophthalmoscope/auriscope | 1 unit | |

1 Allen B. The Faber book of exploration. London: Faber & Faber; 2002.

2 Anderson S. Preparations: Ethics of expeditions. In: Johnson C, Anderson S, Dallimore J, et al, editors. Expedition and wilderness medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008:26-29.

3 Anderson SR, Johnson CJ. Expedition health and safety: A risk assessment. J R Soc Med. 2000;93:557.

4 Barrow C. Risk assessment and crisis management. In: Warrell D, Anderson S, editors. Expedition medicine. London: Profile Books, 2002.

5 Bazian Ltd. Do nurse practitioners provide equivalent care to doctors as a first point of contact for patients with undifferentiated medical problems? Evid Based Healthcare Public Health. 2005;9:179.

6 Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, ed 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994.

7 Boukreev A, Weston de Walt G. The climb: Tragic ambitions on Everest. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1997.

8 Branthwaite M, Beresford N. Law for doctors: Principles and practicalities. London: Royal Society of Medicine; 2003.

9 British Standard 8848. http://www.standardsuk.com/products/BS-8848-2007-A1-2009.php.

10 Cogo A, Fischer R, Schoene R. Respiratory diseases and high altitude. High Alt Med Biol. 2004;5:435.

11 Cordes K. Young guns of North America. In: Goodwin S, editor. The Alpine journal. London: The Alpine Club and The Ernest Press; 2009:38-49.

12 Dallimore J. Expedition first aid training. In: Warrell D, Anderson S, editors. Expedition medicine. London: Profile Books, 2002.

13 Dallimore J, Cooke FJ, Forbes K. Morbidity on youth expeditions to developing countries. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13:1.

14 Darwin CR. Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle’s circumnavigation of the globe in three volumes. London: Henry Colburn; 1838.

15 Douglas E. Chomolungma sings the blues. London: Constable & Co; 1997.

16 Duff A. Legal liability in expedition medicine. In: Warrell D, Anderson S, editors. Expedition medicine. London: Profile Books, 2002.

17 Everest ER–Himalayan Rescue Association, http://www.everester.org/.

18 Fernández-Armesto F. Pathfinders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

19 Fiennes R. Captain Scott. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 2003.

20 Finch G. Der Kampf um den Everest (The Struggle for Everest). Trowbridge, UK: Cromwell Press; 2008.

21 Freer L. Descriptive report of experience designing and staffing the first-ever medical clinic at Mt. Everest base camp, 2003. High Alt Med Biol. 2004;5:89.

22 Glairon-Rappaz P, Steck U, Hiraide K, et al. Piolets d’Or. In: Goodwin S, editor. The Alpine journal. London: The Alpine Club and The Ernest Press; 2009:51-77.

23 Good medical practice, http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice/good_clinical_care_treatments.asp.

24 Goodyer L. Medical kits and the self-management of first aid and minor medical conditions for travelers. In: Travel medicine for health professionals. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2004:279-283.

25 Goodyer L, Rajani M. Carrying medicines across international borders. J Br Travel Health Assoc. 2009;13:35.

26 Hackett P. High altitude and common medical conditions. In: Hornbein T, Schoene R, editors. High altitude: An exploration of human adaptation. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2001:839-885.

27 Hansen T. Critical conflict resolution theory and practice. Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 2008;25:403.

28 Hauser M, Mueller A, Swai B, et al. Deaths due to high altitude illness among tourists climbing Kilimanjaro (abstract). South African Travel Health Meeting. 2004.

29 Hedin S. My life as an explorer. New York: Garden City Publishing; 1925.

30 Heil N. Dark summit. New York: Henry Holt Co; 2008.

31 Henderson BB. True North: Peary, Cook, and the race to the Pole. London: WW Norton & Co; 2005.

32 Herzog M. Annapurna: Premier 8000. Paris: Arthaud; 1951.

33 Higgins JP, Tuttle T, Higgins JA. Altitude and the heart: Is going high safe for your cardiac patient? Am Heart J. 2010;159:25.

34 Hillebrandt D. A year’s experience as advisory doctor to a commercial mountaineering expedition company. High Alt Med Biol. 2002;3:409.

35 Hillebrandt D: Personal communication.

36 Houston C, Bates R. K2: The savage mountain. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co; 1954.

37 . How trekkers risk reaching a fatal high on Africa’s biggest peak. The Guardian Newspaper, 2007, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/mar/31/travel.travelnews.

38 Hunt J. The ascent of Everest. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1953.

39 Illingworth R. Expedition medicine: A planning guide. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1984.

40 [In praise of … climbing Kilimanjaro. The Guardian Newspaper, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/mar/12/climbing-kilimanjaro, 2009.

41 International Narcotics Control Board, http://www.incb.org/incb/guidelines_travellers.html, 2010.

42 Kilimanjaro. It makes you sick. The Guardian Newspaper, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/feb/24/kilimanjaro-chris-moyles.

43 Kilimanjaro porters need better care, Kilimanjaro Porters Assistance Project. http://www.kiliporters.org/.

44 Kodas M. High crimes: The fate of Everest in an age of greed. New York: Hyperion; 2008.

45 Krakauer J. Into thin air. New York: Villard Books; 1997.

46 Luks AM, Swenson ER. Travel to high altitude with pre-existing lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:770.

47 Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. BMJ. 2002;325:697.

48 Martindale MR. Another night at the Himalayan Rescue Association Aid Post in Pheriche, Nepal: The porter who fell 300 m. High Alt Med Biol. 2007;8:253.

49 Mason N. Mera Peak pains. In: The Alpine Journal. London: The Alpine Club and The Ernest Press; 2008:227-236.

50 Medical Defence Union: Personal communication.

51 Mieske K, Flaherty G, O’Brien T. Journeys to high altitude—risks and recommendations for travelers with preexisting medical conditions. J Travel Med. 2010;17:48.

52 Mountaineering medical conference warns of risks faced by charity trekkers, the British Mountaineering Council. http://www.thebmc.co.uk/News.aspx?id=1088.

53 Mountain medicine. http://www.theuiaa.org/mountain_medicine.html.

54 [revised. Oxford dictionary of English, ed 2. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005..

55 Rimoldi SF, Sartori C, Seiler C, et al. High-altitude exposure in patients with cardiovascular disease: Risk assessment and practical recommendations. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;52:512.

56 Sadnicka A, Walker R, Dallimore J. Morbidity and determinants of health on youth expeditions. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:181.

57 Sagarmatha National Park Nepal. United Nations Environment Program–World Conservation Monitoring Centre. http://www.unep-wcmc.org/sites/wh/pdf/Sagarmatha.pdf, 2008.

58 Sakr M, Kendall R, Angus J, et al. Emergency nurse practitioners: A three part study in clinical and cost effectiveness. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:158.

59 Shaw M, Dallimore J. The medical preparation of expeditions: The role of the medical officer. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2005;3:213.

60 Simpson J. Dark shadows falling. London: Jonathan Cape; 1997.

61 Somervell T. After Everest. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1936.

62 Stanley HM. How I found Livingstone: Travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa, including an account of four months’ residence with Dr. Livingstone. New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co; 1872.

63 Tilman H. The ascent of Nanda Devi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1937.

64 Trekking ethics. http://ippg.net/trekking-ethics/.

65 UK Nursing and Midwifery Council: Personal communication.

66 Unsworth W. Everest: The mountaineering history. revised, ed 3. Baton Wicks, London, 2000..

67 Ward MP. Everest 1953, first ascent: A clinical record. High Alt Med Biol. 2003;4:27.

68 Welch TR, Clement K, Berman D. Wilderness first aid: Is there an “industry standard”. Wilderness Environ Med. 2009;20:113.

69 West J. High life: A history of high-altitude physiology and medicine. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press for the American Physiological Society; 1998.

70 West JB, Alexander M. Kellas and the physiological challenge of Mt Everest. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:3.

71 Wootton R, Craig J, Patterson V. Introduction to telemedicine. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd; 2006.

Advise and brief the team on medical issues (general and specific to expedition environment).

Advise and brief the team on medical issues (general and specific to expedition environment). Undertake medical screening of all expedition members.

Undertake medical screening of all expedition members. Encourage all participants to have a pre-expedition dental checkup.

Encourage all participants to have a pre-expedition dental checkup. Provide advice on immunizations and malaria prophylaxis.

Provide advice on immunizations and malaria prophylaxis. Organize appropriate first-aid training for all expedition members.

Organize appropriate first-aid training for all expedition members. Obtain, pack, and transport medical supplies and kits.

Obtain, pack, and transport medical supplies and kits. Undertake a risk assessment, and prepare associated documents.

Undertake a risk assessment, and prepare associated documents. Investigate local health services and medical facilities.

Investigate local health services and medical facilities. Consider the effects of weather and natural disasters such as tsunami, volcanic eruption, earthquake.

Consider the effects of weather and natural disasters such as tsunami, volcanic eruption, earthquake. Prepare a communication network in case of evacuation.

Prepare a communication network in case of evacuation. Organize medical insurance with full emergency evacuation coverage.

Organize medical insurance with full emergency evacuation coverage. Confirm that professional indemnity insurance will cover expedition medical officer role.

Confirm that professional indemnity insurance will cover expedition medical officer role. Hazard

Hazard Risk

Risk Risk level

Risk level Control measures

Control measures Additional action

Additional action Review mechanism

Review mechanism The importance of clean water and hygienically prepared food

The importance of clean water and hygienically prepared food Dangers of the sun—sunburn, dehydration, and heat illnesses

Dangers of the sun—sunburn, dehydration, and heat illnesses The need for good personal hygiene to prevent skin and other infections

The need for good personal hygiene to prevent skin and other infections Promoting sexual health by avoiding risky sexual activity

Promoting sexual health by avoiding risky sexual activity Awareness of emotional problems such as isolation, homesickness, conflict within the group

Awareness of emotional problems such as isolation, homesickness, conflict within the group Drug-taking behavior must be avoided, and alcohol should be used only in moderation

Drug-taking behavior must be avoided, and alcohol should be used only in moderation Avoiding bites and stings, the use of insect repellents, and dangers of walking barefoot

Avoiding bites and stings, the use of insect repellents, and dangers of walking barefoot Special risks for some activities such as high-altitude mountaineering, scuba diving, kayaking, sailing

Special risks for some activities such as high-altitude mountaineering, scuba diving, kayaking, sailing Appropriate pre-expedition immunizations and choice of suitable antimalarials

Appropriate pre-expedition immunizations and choice of suitable antimalarials Pre-expedition fitness, including a dental checkup

Pre-expedition fitness, including a dental checkup Preparation of a suitable personal first-aid kit and first-aid training tailored to the environment and activities planned

Preparation of a suitable personal first-aid kit and first-aid training tailored to the environment and activities planned Blister kit

Blister kit Adhesive plasters and dressings

Adhesive plasters and dressings Antiseptic wipes

Antiseptic wipes Simple analgesic—acetaminophen or preferred painkiller

Simple analgesic—acetaminophen or preferred painkiller Antihistamine tablets

Antihistamine tablets Hydrocortisone cream—chlorphenamine (Piriton) tablets

Hydrocortisone cream—chlorphenamine (Piriton) tablets Antiemetic and oral rehydration sachets

Antiemetic and oral rehydration sachets Personal medication, including antimalarials if appropriate

Personal medication, including antimalarials if appropriate Insect repellent and sunblock

Insect repellent and sunblock