CHAPTER 4 Expanders and Breast Reconstruction with Gel and Saline Implants

Key Points

Introduction

Clinical use of tissue expansion dates back to 1957 where expanded postauricular skin was used to reconstruct a traumatic ear defect.1 Subsequent interest in this technique, and specifically its application to breast reconstruction, did not flourish until 20 years later when Radovan and Austad developed silicone tissue expanders, independently presenting their results in 19782 and 1979.3 Radovan described a saline-filled implantable silicone expander utilizing a port; Austad described a self-inflating tissue expander4 including a description of the histological features of expanded tissue.5,6 As the safety and efficacy of submuscular tissue expansion has improved, implant-based breast reconstruction has become one of the most frequently employed reconstructive techniques in eligible patients. Today, an understanding of implant reconstruction results through careful planning of tissue expander placement and judicious modification of the pocket at the time of permanent implant exchange is resulting in a more realistic appearance to the reconstructed breast, while technologic advances in implant design and biologic substitutes are providing improved soft tissue coverage, contour and a more realistic feel to implant-based breast reconstruction.

Indications and Patient Selection

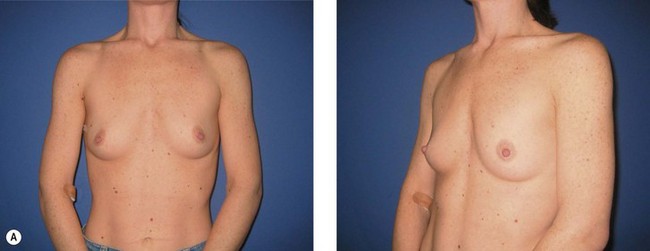

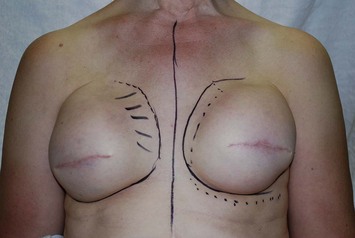

The ideal candidate for implant-based reconstruction is the patient with durable, non-redundant soft tissue coverage desiring a moderate sized non-ptotic breast (Fig. 4.1). This allows for flexibility in final size, tends to create a more stylized contour of the breast, and is particularly well suited to bilateral reconstruction. In unilateral reconstruction the patient must be willing to entertain the possibility of contralateral breast augmentation, reduction, or mastopexy. These considerations hold true for immediate or delayed reconstruction patients. However, the delayed reconstruction patient who has received postmastectomy radiation therapy should be approached very cautiously as the complication rate in this setting may be exceedingly high7 (Fig. 4.2). Also, large-breasted patients who wish to maintain a large size in their reconstruction may not be able to achieve this with tissue expansion and implants. Tissue expansion may altogether be avoided in carefully selected patients who have received a skin-sparing mastectomy (e.g., prophylactic mastectomy) with unequivocally viable skin flaps. However, in those patients with significant soft tissue loss at the time of tumor extirpation, tissue expansion is usually necessary.

Radiation Therapy and Implant-Based Reconstruction

Radiation therapy may be administered before mastectomy in the instance of prior breast conservation therapy, immediately following mastectomy but before reconstruction, coincident with tissue expansion, or after completion of tissue expansion. Radiation therapy has traditionally been avoided in patients with T0, T1 or T2 tumors after mastectomy, based on the patient’s choice, rather than lumpectomy with radiation as defined in the NSABP-B-06 trial.8 However, an increasing number of patients desiring breast reconstruction are eligible for radiotherapy due to the increasing prevalence of breast cancer and expanding indications for adjuvant therapy.9 In 1999 the indications for radiation therapy for breast cancer after mastectomy were expanded to include patients with stage II disease having either a primary tumor diameter greater than 5 cm (T3) and/or four or more involved lymph nodes (Table 4.1).10 Currently the efficacy of radiation therapy in patients with one to three affected lymph nodes is in phase III trials (NSABP-B-39).11

As such, an understanding of the effects of radiation therapy on the reconstructive surgeon’s strategy has become increasingly important. Radiation therapy by itself is no absolute contraindication to implant-based reconstruction, but its limitations must be realized, and some surgeons may wish to avoid attempting to expand skin with anticipated irradiation. While the need for radiation may be determined prior to mastectomy in a subset of patients, an increasing number are offered postoperative radiation therapy following analysis of the permanent pathology of lymph nodes or tumor margins. Delayed primary reconstruction, in which the tissue expander is placed 3 or 4 days after mastectomy, may be performed to ensure negative pathology and no indication for radiation. In those patients where radiation therapy is indicated based on intraoperative findings such as tumor size, narrow margins or sentinel lymph node status, the reconstructive surgeon should reserve the option to ‘walk away’ from an immediate reconstruction. Some authors have suggested the use of a delayed-immediate reconstruction technique, where a partially inflated expander is placed immediately with interval deflation for the duration of radiation therapy, if indicated.12 In this circumstance of postoperative radiation, we prefer to expedite the expansion process to completion within 4 to 5 weeks, before radiation therapy is started.

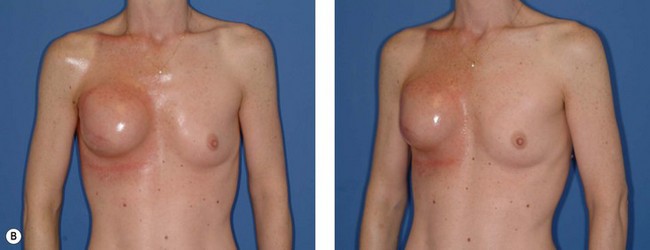

In most centers, radiation oncologists do not perceive the tissue expander as a hazard to good treatment. If oncologic considerations require radiation prior to that time, delayed reconstruction is preferred. Those patients who have received even appropriately titrated radiation therapy are at greater risk for mastectomy flap necrosis, implant exposure or inability to complete tissue expansion (Fig. 4.3). However, a successful result can nonetheless be obtained (Fig. 4.4). As such, we often allow patients to ‘prove’ the expander will not work before resorting to autologous forms of reconstruction. Ultimately, autologous tissue coverage may be required to achieve an acceptable contour. Spear reviewed a series of saline implant-reconstructed women receiving radiation therapy at various time points relative to reconstruction and found autologous tissue was needed in 19 out of 40 (47.5%) patients primarily as a consequence of contracture or unsatisfactory implant position.13 These secondary operations still make use of the expanded tissue, and may be thought of as an adjunct to implant-based reconstruction, rather than salvage for a failed operation. No additional operations are required than if the patient had proceeded to autologous tissue transfer, initially or at a later date; the only disadvantage is the time and inconvenience for the patient having undergone an expansion process that does not progress to completion or ultimately fails. In those secondary or delayed reconstruction patients who have received very high doses of radiotherapy, we do not attempt tissue expansion alone, and proceed directly to autologous tissue transfer with or without the use of an implant and expander.

Preoperative Marking and Tissue Expander Selection

Preoperative coordination with the surgical oncologist is critical for obtaining a favorably placed mastectomy scar that can be concealed by clothing with preservation of as much skin envelope as needed. The importance of preserving the inframammary fold should be appreciated by the oncologic surgeon. With greater acceptance of skin-sparing and areola-sparing mastectomies, incisions other than a standard periareolar ellipse may affect surgical exposure (Fig. 4.5). In the large-breasted patient who wants significantly smaller breasts and has no indication for radiation, a mastectomy scar incorporating a vertical component, or based on an inverted ‘T’ incision as seen in Wise pattern breast reductions, may be considered (see Fig. 4.27).

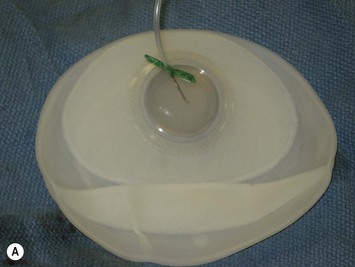

With the final result in mind, tissue expanders of appropriate dimensions are ordered prior to the surgery. A range of tissue expanders are currently available, including round and contoured expanders, the latter offering the benefit of differential, greater lower pole expansion, and an increasing slope from the upper pole. Most expanders utilize an integrated valve that is located using a magnetic port finder (Fig. 4.6). If expander positioning is ideal, a remote port expandable implant provides an option of explanting only the port and interconnecting catheter, leaving the implant in place as a permanent device. Each tissue expander has a specific base diameter, height, contour profile (e.g., low, moderate, and tall), and maximum recommended volume (Fig. 4.7). We use base diameter as the primary determinant of implant choice with volume as the second consideration. The choice of profile is largely based on the habitus of the patient, with narrow-chested, thinner patients appearing proportional with low or medium profile expanders and heavier patients requiring a tall profile to offer projection commensurate with their larger size.

Operative Technique: Immediate Reconstruction

Patient positioning

Pocket dissection

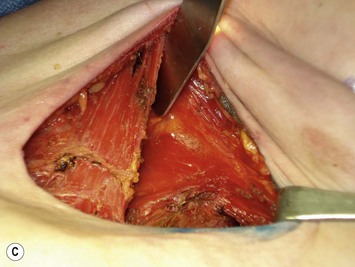

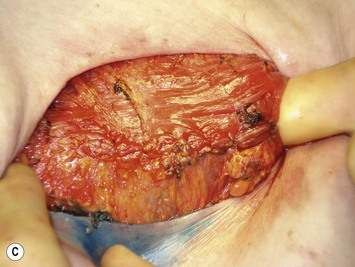

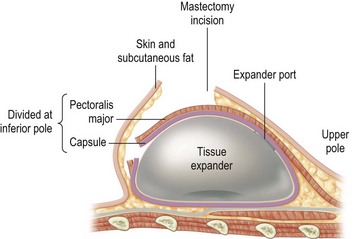

With the deficiency of soft tissue coverage resulting from the mastectomy, partial or complete muscle coverage is necessary to limit implant visibility or exposure. We prefer complete muscular coverage of the expander to maximize the vascularity of the pocket and exclude the implant from the overlying mastectomy incision. In this technique, the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle is elevated and a submuscular pocket is dissected medially to the sternal edge and superiorly to the second rib. The superior dissection is made in a relatively avascular plane between the pectoralis major and minor muscles. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the thoracoacromial pedicle located on the undersurface of the pectoralis major muscle. A systemic paralytic may be administered to make the superior dissection easier, as powerful contractions of the pectoralis major may result from electrocautery dissection near its dominant neurovascular pedicle. Superior dissection may be made bluntly, and while technically easy, excess dissection in this direction may lead to implant malposition, as the expander is wider than it is tall. When possible, the large perforator in the medial second interspace is preserved because of its contribution to the mastectomy flap blood supply (Figs 4.8 and 4.9A–C).

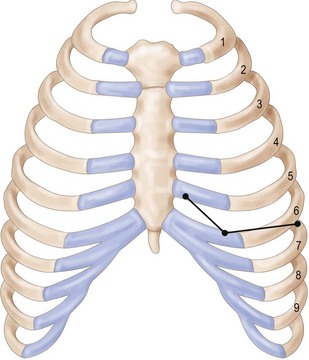

Inferiorly, the pocket dissection is carried down to the top of the sixth rib at the meridian of the breast. In general, the inframammary fold (IMF) can be reliably reconstructed in this location. Although the anatomy of the IMF is not firmly established and may vary with age and body habitus, it is an anatomic landmark with gross anatomic dissections and histologic reports suggesting a confluence of organized collagen fibers in the dermis14 and/or an actual ligament arising from periosteum and intercostal fascia.15 With the normal curve of the ribcage, the medial IMF is predictably located at the bottom of the fifth rib and the lateral extent of the fold is located at the top of the seventh rib (Fig. 4.10). Avoidance of dissection below the fold is the preferred strategy. Because the pectoralis major muscle inserts at the fifth rib, cephalad to the IMF, it is necessary to detach its inferior origins to position the expander appropriately. When the mastectomy has not violated the IMF, this release may be carried into the subcutaneous tissue of the IMF without compromising the expander coverage inferiorly. However, it is often necessary to elevate a portion of the anterior rectus fascia in continuity with the released pectoralis to maintain complete expander coverage.

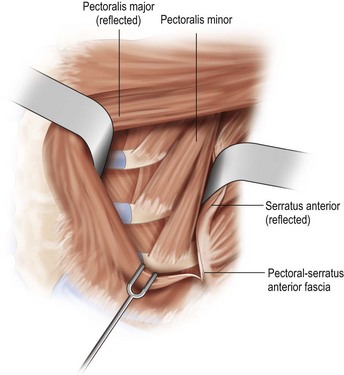

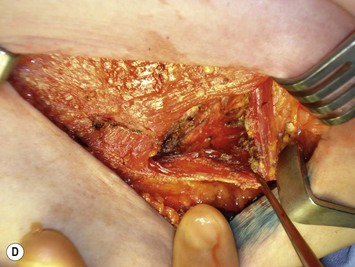

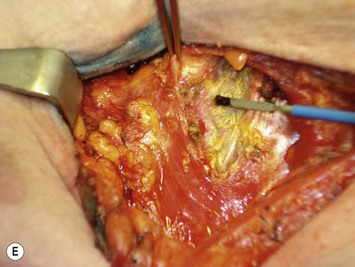

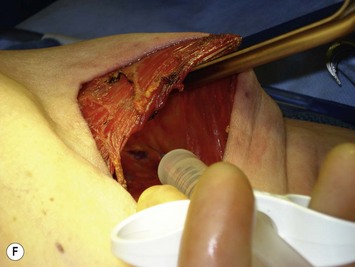

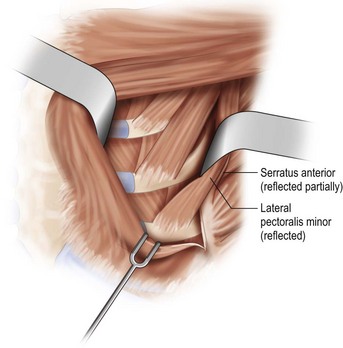

The lower slips of the serratus anterior are elevated to cover the infralateral expander (Fig. 4.9D). Maintaining the bridging fascia between the pectoralis major and the serratus anterior is very helpful in this dissection (Fig. 4.9E). Care must also be taken to avoid dissection through the intercostal spaces. A complementary adjunct to complete elevation of the serratus anterior is to elevate the lateral edge of the pectoralis minor in continuity with the lower slips of the serratus (Fig. 4.11). This has the benefit of better retention of the implant at the superolateral pocket border, helping to prevent any late migration towards the axilla, particularly after lymph node dissection. These dissections are performed to match the footprint of the desired expander, respecting the desired landmarks of the future reconstructed breast. Proper control of the pocket dimensions will limit the potential for expander malposition or malrotation. When possible, muscle relaxation provided by the anesthesia team will facilitate the pocket dissection. As an adjunct to post-operative pain management and to prevent muscle spasms, 0.25% bupivacaine can be injected near the thoracoacromial pedicle and as a field block around the perimeter of the pocket (Fig. 4.9F).

Fig. 4.11 Technique for raising lateral slips of pectoralis minor to achieve superolateral muscular coverage.

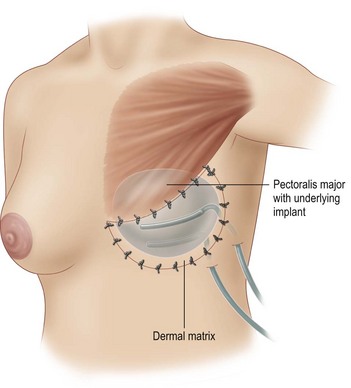

An alternative to complete muscle coverage of the expander has emerged. An acellular dermal matrix may be used as a hammock for the expander to avoid the necessity of elevation of the rectus fascia, serratus and/or pectoralis minor muscle.16 It is also useful in those situations where complete muscle coverage was desired but the mastectomy resulted in loss of fascia or muscle integrity in the inferior pocket. Typically, an 8 × 16 cm sheet of dermal matrix is sutured superiorly to the detached pectoralis major muscle edge and medially at the sternal edge (Fig. 4.12). We use interrupted 2-0 silk sutures for this purpose. Inferiorly and laterally, it is sutured to the underlying fascia. The IMF landmarks and the desired lateral contours determine the position. It is recommended that the dermal side of the graft is directed towards the undersurface of the mastectomy flaps to promote vascular ingrowth. While an effective technique without a known increase in complications, the acellular dermal matrix adds considerable cost and may increase the risk of seroma. In the setting of an ischemic mastectomy flap, expander protection from infection or exposure may be compromised. Additionally, the effect of post-expansion radiation on the vascularization of the acellular dermal graft is not fully known. Although it has been successfully used in this scenario, deliberate patient selection is necessary to achieve optimal results.

Expander placement

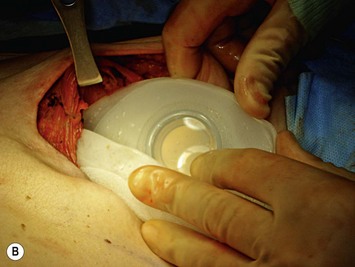

The expander is removed from the sterile internal packaging only when ready for placement to reduce the possibility of implant contamination. Hemostasis within the pocket should be assured: perforating vessels, if visible at the medial pocket edges should be cauterized for risk of avulsion following future expansion. Prior to the insertion of the expander or a permanent implant, the pocket is irrigated to remove cautery char, loose fat, and to visualize any remaining bleeding. Many different irrigant solutions have been proposed: the ‘triple antibiotic’ solution popularized by Adams contains gentamicin (80 mg), cefazolin (1 g) and bacitracin (50,000 U) in 500 ml of normal saline, with vancomycin substituted for bacitracin at some institutions.17 It must be noted that the endpoint of this study, capsular contracture in breast augmentation patients, was based on an etiologic assumption of subclinical pocket infection, which has not been firmly established. No comparative efficacy has been established with any popular irrigation choices including triple antibiotic, single antibiotic, diluted povidone–iodine or normal saline alone, particularly in breast reconstruction patients, and the additional cost of these measures should be considered if implementing them systematically. We do employ well-established barrier precautions – the operating surgeon applies new sterile gloves and is the only team member to handle the implant. Some air is present in the expander when removed from the packaging. We typically evacuate the air maximally to minimize risk of tearing tissues during pocket insertion. The expander is then positioned so that the integrated valve is at the upper pole. Some additional pocket dissection may be required to achieve this; however, effort is made to keep within the appropriate base diameter. Certain tissue expander models have a reinforced orientation tab at the posterior aspect where an absorbable stitch can temporarily secure the implant to rib periosteum or intercostal fascia to prevent malposition. The expander is then filled with 60–120 cc of saline from a closed system, based on the condition of the overlying skin and muscle. This intraoperative expansion allows the lower pole of the implant to unfurl, facilitating positioning and has the secondary benefit of obliterating any dead space within the pocket.

Once expander position is satisfactory and it is apparent that the implant pocket can be closed without excessive tension, the lateral free edge of the pectoralis major is sewn to the free edge of the serratus anterior and pectoral-serratus fascia in the case of total submuscular placement, or to the free edge of the dermal matrix if used. The overlying muscle is closed and additional saline is added using the sterile magnetic port finder to achieve an acceptable amount of tension on skin and muscle closure (Fig. 4.13). Total intraoperative expansion may range widely depending on overlying soft tissue laxity, but approximately 20% of the implant volume should be tolerated in most patients. The use of dermal matrix approximately doubles the intraoperative volume expansion possible.

Delayed Reconstruction

Implant-based reconstruction may be delayed to facilitate completion of chemo- or radiation therapy, but subsequent tissue expansion is usually necessary. Patient marking is done preoperatively to estimate the boundaries of the ideal implant pocket that will provide the final desired result (Fig. 4.14). If the contralateral breast is used as a template, any planned symmetry procedure should be accounted for in estimation of pocket size. The surgical approach is similar to that of primary reconstruction. The scar is excised and the skin flaps are elevated although not to the same extent as would be seen immediately after a mastectomy. After exposure of the inferior portion of the pectoralis major it is possible to create the submuscular pocket in the same fashion as previously described by identifying and reflecting its lateral border. Another option is to create the pocket through a pectoralis muscle-splitting incision (Fig. 4.15). This has the benefit of preserving functional muscle fibers with a natural tendency to close the incision upon contraction and is less likely to disrupt the inframammary fold. The muscle fibers are oriented perpendicular to the skin incision, providing more durable coverage in the event of skin necrosis, but more extensive dissection of the skin flaps is required. Because the skin flaps are functionally delayed by the prior mastectomy, it is less critical to achieve complete lateral muscular coverage. It is usually not necessary to elevate the anterior rectus fascia, serratus anterior muscle, or pectoralis minor muscle to maintain satisfactory coverage of the expander. The same landmarks are utilized in dissecting the pocket for delayed reconstruction as are used in immediate reconstruction in terms of the location of the IMF in relation to the underlying ribs. Accurate pocket dissection is equally important here to reduce the risk of malposition and malrotation. Primary closure of the muscle splitting incision is performed and expansion under direct visualization is performed to assess tension. Despite loss of skin domain in the setting of delayed reconstruction, it can be combined successfully with immediate reconstruction for a reasonably symmetric result (Fig. 4.16).

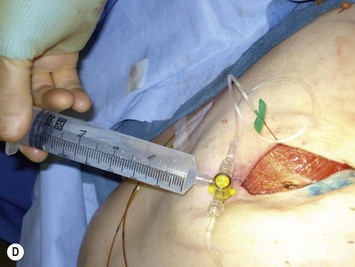

Drain Management

Drains are typically placed after immediate reconstruction, especially after axillary dissection, but rarely in delayed or second stage reconstruction. Prior to skin closure, a closed bulb suction drain is placed over the pectoralis muscle so that it is not in contact with the implant. If dermal matrix is used, often a well-tunneled drain placed inside the implant pocket may be advisable due to reports of increased drainage volumes18 (Fig. 4.12). Drains are typically removed when drainage is less than 30 ml over a 24-hour period, with many surgeons removing drains at 7–14 days irrespective of output. Any reaccumulation of fluid can be removed postoperatively during the expansion process by aspirations over the area of the fill port. Patients should not get the drain sites wet and should sponge bath rather than shower. Good patient education and meticulous care is essential to prevent an ascending infection originating at the drain site. A first-generation cephalosporin or other empiric coverage for skin organisms is administered for 7–10 days.

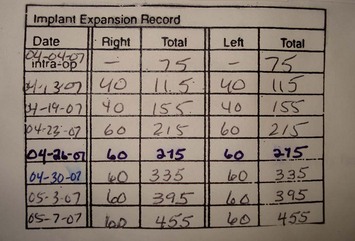

Expansion

The tissue expansion process may begin intraoperatively with 60–1200 cc, or more if dermal matrix is used. Outpatient expansion begins at 10–14 days postoperatively with each fill ranging from 60 to 120 cc (Fig. 4.17). The magnetic port finder is used to locate the integrated valve and a 21-gauge needle attached to IV tubing is used to transfix the valve. Early in the expansion process, the interposed soft tissue may be thick and a long needle length (5 cm or greater) is necessary. As more expansion is achieved, the soft tissue thins considerably and a shorter butterfly needle is suitable. Tissue expansion results in temporary ischemia and inflammation that is minimized with smaller, more frequent fills. Expansion is repeated at 1 to 4 week intervals and often the patient will determine the rate of expansion, as there is some discomfort with each fill.

Adjuvant therapy and tissue expansion

Radiation therapy is associated with an increased risk of infection, contracture and wound complications when combined with prosthetic implants19 and ongoing expansion places considerable risk of dehiscence on an irradiated incision. Ideally, tissue expansion should proceed to completion before initiation of radiation therapy. In our center, radiation therapy typically begins 6–8 weeks after mastectomy, allowing adequate time for full expansion.

Second Stage Reconstruction

Preoperative markings and implant selection

Ideally, the position of the permanent implant should be no different from that of the tissue expander, and little or no modification is required, but this is rarely the situation. Most patients benefit from a minor revision of the pocket. In the event of expander migration or rotation, areas of capsulotomy or capsulorraphy are marked (Fig. 4.18). A superomedial capsulotomy to enhance cleavage and lateral capsulorraphy to medialize the pocket in the event of lateral migration are typical adjustments. The base diameter of the breast is again confirmed and is a primary deciding factor in choice of permanent implants to have in the operating room. It is important to realize that the tissue expander comprises approximately 65–100 cc of volume and this should be factored in the permanent implant volume selection.

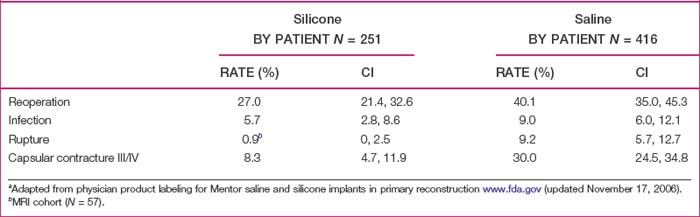

The choice of saline or silicone implants is left to the patient. Saline implants may offer greater projection in the larger patient, while the thin patient likely will prefer the surface camouflage and feel of silicone-filled implants. With respect to adverse events, we use the product information data provided by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on saline and gel implants to educate the patient regarding risks with emphasis on rupture, Baker grade III/IV contracture and overall reoperation (Table 4.2).20 In preoperative counseling we quote a 1% per year per breast reoperation rate for contracture, based on the Mentor CPG MemoryGel study that showed 5.2% rate of Baker grade III/IV contractures at 2 years in 251 primary reconstruction patients.21 For those patients that use a silicone implant, the FDA recommendation of 3 year post-implant magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with follow up MRI every 2 years is explained to the patient, but we candidly recognize the clinical and practical limitations and controversy of using MRI as a screening tool for asymptomatic implant reconstructions.22 In absence of MRI screening, yearly follow up with clinical exam should be sufficient and may be the best clinical practice.

Table 4.2 Comparison of 3-year cumulative first occurrence Kaplan-Meier adverse event risk ratesa by implant type

The issue regarding the choice of textured versus smooth implants warrants mention. Although once believed to reduce the incidence of capsular contracture, textured round implants have been shown to have no better outcomes than smooth devices in this respect, and are regarded by many to have an increased rate of palpability, rupture, visible wrinkling, and lack of dynamic motion.23 Form-stable textured implants have been used internationally and are currently under evaluation in the United States. Although these devices offer the theoretic advantage of a more realistic shape, the textured surface necessary to anchor the implant in position may present aesthetic issues. Also, the form-stable design may be unforgiving of slight degrees of malposition, and the importance of precise pocket dissection to avoid rotation should be emphasized.

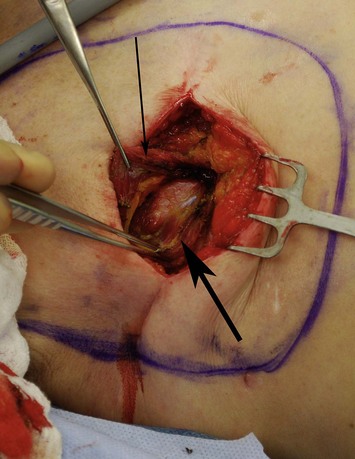

Surgical approach

The second stage approach begins by excising the mastectomy scars that have often widened after the expansion process. If an identifiable muscle layer is present, the muscle-splitting approach described previously may be used. Often the muscle is attenuated and difficult to identify as a layer distinct from the capsule. In this case the muscle and capsule are divided as far inferiorly as possible by raising the inferior mastectomy skin flap. This results in optimal coverage by ‘staggering’ the skin and muscle/capsule layers (Fig. 4.19). A secure multi-layer closure is particularly critical in patients with poor healing capabilities following radiation. The expander port is transfixed and partially deflated to allow intact removal without excessive stretch or tearing of the capsulotomy. This is an important precaution because while the expander and permanent implant fill volumes may be equivalent, the expander shell is somewhat bulkier with stiff components, such as the integrated port. The expander shell also adds approximately 65–100 cc to the fill volume, in comparison to the negligible volume of the permanent implant silicone shell. Actual total expansion volume can be confirmed by volume displacement in saline, in addition to what was aspirated from the expander to facilitate its removal.

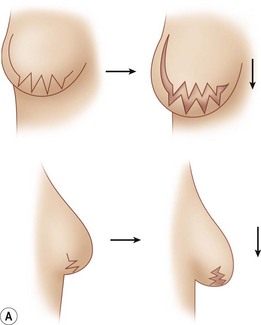

Complete capsulectomy at the time of second stage reconstruction is not recommended because of the loss of soft tissue coverage, possible injury to the blood supply of the overlying skin and increased inflammation. Rather, directed capsulotomy and/or capsulorrhaphy are used to provide optimal positioning and shaping. In general, a circumferential capsulotomy into the subcutaneous fat is performed around the base of the pocket. A ‘zigzag’ inferior pole capsulotomy will allow for lower pole distension and overhang (Fig. 4.20). When performing inferior capsulotomies, it is necessary to divide any remaining pectoralis muscle fibers to gain the necessary relaxation. When acellular dermal matrix has been used to provide lower pole coverage, it has functionally become a part of the lower pole capsule. It should be incised similarly if needed to provide the desired contour of the lower pole. In those patients with extremely thin lower pole soft tissue coverage, care should be taken to avoid dermal injury or ‘button-hole’ perforation. Upper pole capsulotomies are performed sparingly to prevent bulging in the upper breast. Additional directed capsulotomies are performed as needed to allow for expansion of the pocket to achieve the desired contour. Conversely, capsulorrhaphy sutures of 2-0 silk may be necessary to correct areas of overexpansion and meet the needs of the desired permanent implant dimension. Accurate pocket positioning is necessary for optimal results. Control of the pocket with the initial expander placement will obviate the need for significant pocket manipulation at the second stage.

Re-establishing the inframammary fold

Ideally the inframammary fold is preserved following the original mastectomy and, if not, it is re-established at the time of tissue expander placement. A fold that appears too high may be a result of insufficient inferior pocket dissection and inferior capsulotomy will address this. If the fold has been lowered by expander migration, it should be re-established internally. From within the pocket, the undersurface of the mastectomy flap is sutured internally to the expander capsule at the bottom of the fifth rib medially, the middle of the sixth rib at the meridian and the top of the seventh rib laterally (Fig. 4.10). These static landmarks can be located by identifying the second rib at the manubriosternal joint (Angle of Louis). Four to five sutures are needed; braided sutures such as Vicryl or silk are preferred as they are softer and will be in direct contact with the prosthesis.

Complications and Pitfalls

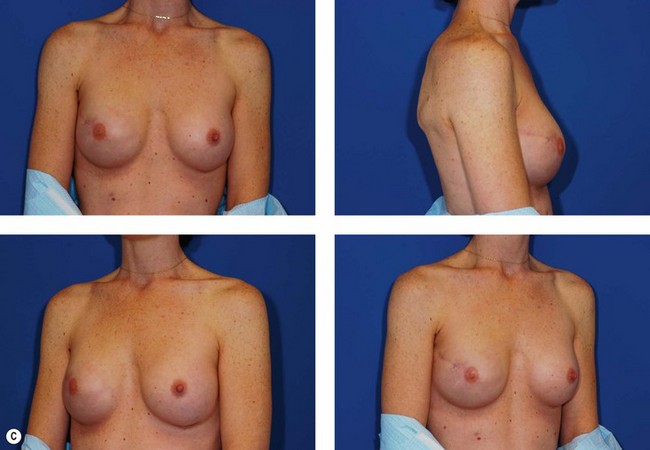

Asymmetric breasts

Unilateral reconstruction or separately timed reconstruction procedures may result in significant differences in size or ptosis that can be corrected at the time of second stage reconstruction. A contralateral breast reduction, mastopexy (Fig. 4.21), or augmentation mastopexy may be required and patients should be informed of the likelihood of future revisions to maintain symmetry. Achieving symmetry with respect to the inframammary fold, nipple position and overall breast size is challenging, particularly in those patients requiring contralateral augmentation mammaplasty. One of the more difficult scenarios is the expanded breast that has received radiation therapy and has a somewhat constricted envelope (Fig. 4.4). This may also be a result of insufficient pocket dissection inferiorly and can be addressed by inferior capsulotomy with avoidance of dissection below the internal rib landmarks.

Loss of pocket control

The implant pocket may be made too large due to excessive tissue expansion or pocket dissection at either first or second stage reconstructive procedures (Fig. 4.22). This should be avoided by adherence to dissection within the breast diameter when performing mediolateral dissection and preservation of the inframammary fold with its re-establishment at the static rib landmarks if necessary. Capsulorraphy may be needed for medial or lateral support.

Implant exposure

In immediate reconstruction, tension and mastectomy flap overdissection are associated with skin flap necrosis at the incision. One of the benefits to complete submuscular placement is that local wound care is all that is necessary provided skin necrosis is minor and healthy muscle is beneath (Fig. 4.23). When radiation over an expanded implant is poorly titrated, full thickness skin loss remains a possibility. In severe cases, the expander may need to be removed (Fig. 4.24). When the underlying device is a tissue expander, continued expansion to the desired volume or to match a contralateral implant may not be possible and volume must be removed to allow healing subsequent to any necessary debridement. In the event of permanent implant exposure, debridement and immediate wound closure is necessary. If enough skin is lost so that primary closure is not possible, the implant should be removed and additional skin is transferred by autologous reconstruction (Fig. 4.25).

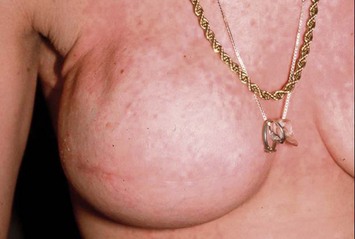

Contracture and visible wrinkling

Capsular contracture is generally regarded to be a more frequent complication in reconstructive than in primary augmentation mammaplasty, presumably because of the significantly reduced soft tissue coverage likely increasing the sensitivity for detection if not the primary incidence. Currently patients are advised that they will likely require a reoperation for contracture at 15 years with an incidence of 1% per breast per year.21 Visible wrinkling may occur with silicone as well as saline implants (Fig. 4.26), but can be best avoided by adequate submuscular implant coverage.

Implant infection

Implant infection (Fig. 4.27) is quoted at 0.2–7% in recent literature.24 It is presumably higher than in primary augmentation mammaplasty because of the decreased soft tissue coverage, longer operating times, and the effects of chemoradiation therapy on the host defense system. Implant removal with drainage and reoperation in 6 months is recommended for severe implant infection. There are reports of implant salvage in circumstances where no frank pus is identified in the implant pocket, and copious antibiotic irrigation and prolonged postoperative targeted antibiotic therapy is used.25,26 The presence of cellulitis near the incision does not necessarily mandate operative exploration, and a trial course of antibiotics is reasonable. Antibiotics cannot be expected to resolve an infected prosthesis or periprosthetic fluid, however. In our institution with a 30% incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), empiric antibiotic therapy consists of prolonged (2–6 weeks) of intravenous vancomycin therapy with the addition of a penicillin for greater bactericidal effect in sensitive organisms. Ultimately, empiric therapy should be tailored according to the prevalence of methicillin resistance at individual institutions. Intraoperative cultures or periprosthetic fluid withdrawn during expansion in the clinic provide a basis for any directed therapy. A trial of implant salvage with antibiotic therapy can be exhausting for the clinician and patient alike, requiring many clinical visits for surveillance of the breast as well as home intravenous antibiotic therapy. While there is occasional success, efforts at salvaging an implant may result in a tremendous expense of time and resources only to result in explantation. Establishing an ‘end point’ at the initiation of therapy, where the implant will be removed if certain goals are not achieved is highly recommended for the sake of everyone involved.

1 Neumann CG. The expansion of an area of skin by progressive distention of a subcutaneous balloon. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1957;19:124.

2 Radovan C. Reconstruction of the breast after radical mastectomy using temporary expander. ASPRS Plast Surg Forum. 1978;1:41.

3 Austad ED, Rose GL. Self-inflating implant for donor tissue augmentation. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, Toronto, Canada, 1979.

4 Austad ED, Rose GL. A self-inflating tissue expander. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70(5):588-594.

5 Austad ED, Pasyk KA, McClatchey KD, Cherry GW. Histomorphologic evaluation of guinea pig skin and soft tissue after controlled tissue expansion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70(6):704-710.

6 Pasyk KA, Austad ED, Cherry GW. Intracellular collagen fibers in the capsule around silicone expanders in guinea pigs. J Surg Res. 1984;36(2):125-133.

7 Kraemer O, Andersen M, Siim E. Breast reconstruction and tissue expansion in irradiated versus not irradiated women after mastectomy. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1996;30(3):201-206.

8 Fisher E, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP): eight-year update of protocol B-17. Cancer. 1999;86:429-438.

9 Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, et al. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: update 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(3):168-183.

10 Harris JR, Halpin-Murphy P, McNeese M, Mendenhall NP, Morrow M, Robert NJ. Consensus statement on postmastectomy radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;15:989.

11 Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Gelber RD, et al. Progress and promise: highlights of the international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2007. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(7):1133-1144.

12 Kronowitz SJ, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM, et al. Delayed immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(6):1617-1628.

13 Spear SL, Onyewu C. Staged breast reconstruction with saline-filled implants in the irradiated breast: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(3):930-945.

14 Muntan CD, Sundine MJ, Rink RD, Acland RD. Inframammary fold: a histologic reappraisal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(2):549-556.

15 Bayati S, Seckel BR. Inframammary crease ligament. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(3):501-508.

16 Breuing KH, Colwell AS. Inferolateral AlloDerm hammock for implant coverage in breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(3):250-255.

17 Adams WP, Rios JL, Smith SJ. Enhancing patient outcomes in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery using triple antibiotic breast irrigation: six-year prospective clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(1):30-36.

18 Glasberg SB, D’Amico RA. Use of regenerative human acellular tissue (Alloderm) to reconstruct the abdominal wall following pedicle TRAM flap breast reconstruction surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(1):8-15.

19 Evans GR, Schusterman MA, Kroll SS. Reconstruction and the radiated breast: is there a role for implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1111.

20 Physician product labeling for Mentor™ saline and silicone implants. http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/breastimplants/labeling.html. (updated November 17, 2006, accessed May 23, 2008)

21 Cunningham B. The mentor study on contour profile gel silicone memorygel breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. December 2007;120(7 Supplement 1):33S-39S.

22 McCarthy CM, Pusic AL, Kerrigan CL. Silicone breast implants and magnetic resonance imaging screening for rupture: do US Food and Drug Administration Recommendations reflect an evidence-based practice approach to patient care? Plast Reconstr Surg. April 2008;121(4):1127-1134.

23 Handel N, Jensen JA, Black Q, Waisman JR, Silverstein MJ. The fate of breast implants: a critical analysis of complications and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(7):1521-1533.

24 Spear SL, Howard MA, Boehmler JH, Ducic I, Low M, Abbruzzesse MR. The infected or exposed breast implant: management and treatment strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(6):1634-1644.

25 Yii NW, Khoo CT. Salvage of infected expander prostheses in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1087-1095.

26 Chun JK, Schulman MR. The infected breast prosthesis after mastectomy reconstruction: successful salvage of nine implants in eight consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(3):581-589.