CHAPTER 24 Expanded Uses of BTX-A for Facial Aesthetic Enhancement

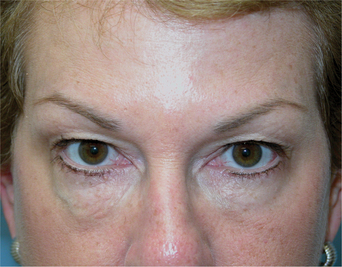

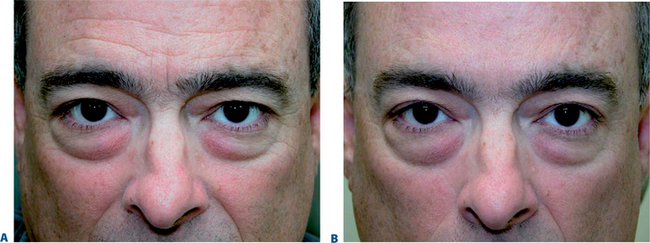

First described in the medical literature in 1992,1 the cosmetic use of botulinum toxin (BTX) has widened to include many previously inconceivable applications. Prior to this discovery, clinical experience with the use of the toxin was primarily limited to an option for the treatment of strabismus and a variety of disorders of chronically increased skeletal muscle tone2 (Fig. 24-1). The application of the toxin for aesthetic improvement was derived from keen observation of the appearance of facial soft tissue in patients who received the drug for a spectrum of disorders related to facial dystonia (Fig. 24-2). The toxin has become not only the gold standard in non-surgical facial rejuvenation, for eradicating dynamic rhytides in the forehead, glabella, around the eyes, and in the lower face and neck, but it has also become a viable alternative, as well as partner to surgery, for facial shaping and contouring.3,4 With essentially no downtime and few complications or adverse effects, the application of BTX in the environment of a comfortable clinical setting, represents the most modern form of cosmetic enhancement that is time-sensitive, safe, and effective (Fig. 24-3).

Treatment of the upper face and periorbita

A number of clinicians, impressed by the toxin’s obvious benefits and high level of safety, experimented with BTX for facial rejuvenation in the late 1980s, prior to the first reports published in the early 1990s.5,6 Although it appears obvious now that cosmetic improvement can be easily afforded by precision application of this agent for dozens of applications, initial enthusiasm was quelled by a lesser understanding of the various causes of facial aging and the possibilities for the use of this drug. Initially used primarily for the treatment of glabellar rhytides, BTX is now a first-line treatment for a number of cosmetic concerns, particularly in the upper face.7–21 To date, the three most common areas treated are the glabella, forehead, and lateral canthus for the treatment of rhytids in the respective regions. Treatment can be applied in various combinations to achieve the desired effect.

Glabellar rhytides

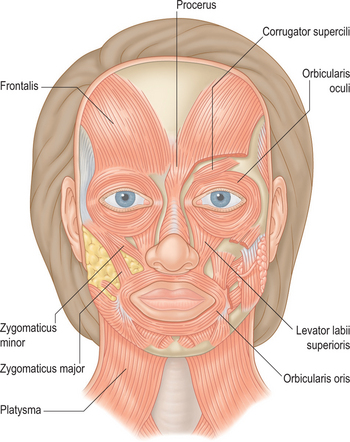

Historically, the ‘glabella’ was the area first and most described as a potential treatment site with BTX for aesthetic enhancement. Currently (at the date of publication) it is still the only facial site with FDA approval for the cosmetic use of BTX, specifically Botox Cosmetic. All other areas for which the toxin is used for cosmetic enhancement are considered ‘off-label.’ This means that under the physician’s discretion it is lawful to apply the drug in other areas with, of course, the appropriate patient consent. The glabella is loosely defined as the region depicted by the smooth elevation of the frontal region just above the bridge of the nose that extends laterally to each side onto and just above and lateral to the medial (head of) the eyebrow. The ‘glabellar complex’ often refers to a group of brow-associated muscles (mostly depressors in action) that function primarily for facial expression (Fig. 24-4). Muscles of the glabellar complex include the corrugator supercilii, procerus, depressor supercilii, and orbicularis oculi. Vertical glabellar frown lines arise naturally from the repeated activity of the corrugator supercilii and medial orbital orbicularis oculi muscles (plus depressor supercilii muscles) that not only induce vertical descent of the medial eye brow but cause adduction and depression of the surrounding soft tissue (Fig. 24-5).

Horizontal lines at the proximal nasal bridge typically located at the most caudal aspect of the glabellar complex are a manifestation of the muscular activity of the procerus and depressor supercilii muscles (Fig. 24-6).

In 1992, Carruthers et al injected 18 patients with BTX-A for the treatment of glabellar frown lines.1 Sixteen of 17 patients followed showed improvement for varying lengths of time with few side effects. This initial paper sparked a frenzy of interest across the globe. Following a number of publications, two randomized, placebo-controlled studies involving 537 patients confirmed the impressive safety and efficacy of the injection on the glabella. This led to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of BTX-A for the treatment of glabellar lines in 2002.22–24 This region has still been the most readily adopted area for the use of BTX for a variety of reasons mentioned previously, as well as a lack of consistent prior effective treatment options.

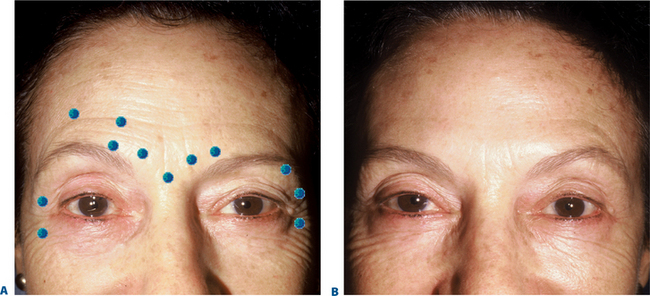

Dosing

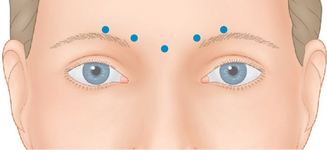

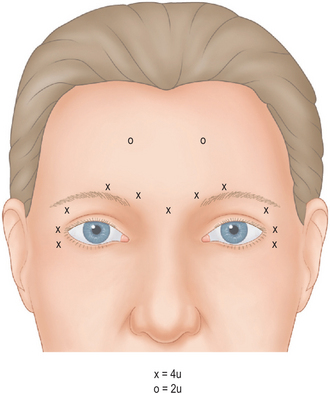

The strength and size of the muscles of the glabellar complex varies significantly from patient to patient. More importantly, despite similar anatomic components in most of us, a greater variable is the individual dynamics (i.e. the way we use our muscles). Although the most common treatment pattern utilizes two injections to each corrugator and one centrally to reduce procerus function (Fig. 24-7), individualizing treatment sites and doses to each patient will optimize clinical benefits. In addition, the exact effect desired may vary as well. In women, recent studies also suggest that higher doses may be longer lasting and give greater aesthetic benefit. A prospective, randomized, dose-ranging study of 80 women showed the greatest responses with the longest duration on glabellar lines with 30 and 40 U BTX-A, compared to the responses seen with only 10 or 20 U.25,26 Moreover, higher doses (20–40 U) produce an additional benefit of eyebrow lift.27 The likely cause for this effect resides primarily in the fact that with higher doses to the glabella region, there is enhancement of diffusion to the adjacent frontalis muscle.28 With this phenomenon, attenuation of the central frontalis activity by BTX induces a secondary hyperdynamic contraction/recruitment of the untreated lateral and superior frontalis that yields this effect (Fig. 24-8). In addition, the desired effects will vary from individual to individual as well. For instance, some individuals might have a more elevated medial eyebrow and prefer a greater lateral arch (Fig. 24-9). Precise and isolated injection placement of toxin to the corrugators and secondary brow depressors (typically a more caudal placement of the injection at or about the brow cilia) could further elevate the medial eyebrow reducing any chance of enhancing the desired brow contour. In these individuals, a ‘high-glabellar’ technique (Fig. 24-10 and DVD) might be preferable. This will affect both the brow depressors and adjacent frontalis muscle, and will reduce the glabellar vertical frown lines as well as induce a varying degree of medial brow descent. This will also be influenced by additional injections (or not) to the more cephalad portions of the forehead and dose (discussed below) (Fig. 24-11).

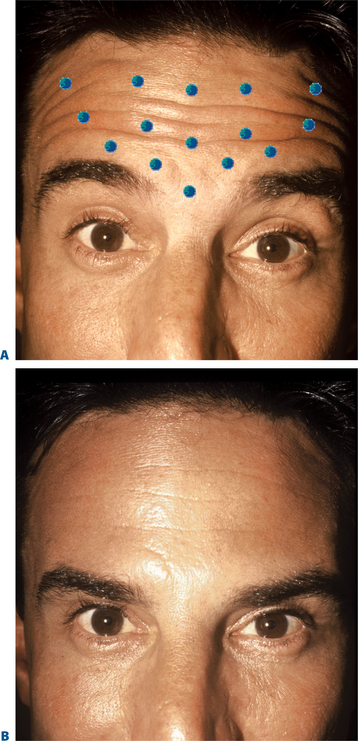

In general, men have a larger glabellar muscle mass compared with women. Studies comparing the efficacy and safety of the ranges of 20 to 80 U of BTX-A in men suggest that patients injected with doses as high as 80 U achieved a ‘better’ response rate than those injected with lower doses, without experiencing an increase in adverse effects.29 This high level dosing produces enhanced efficacy as well as persistence of effect which are not only required due to the greater muscle mass in males, but are also better suited to the male’s gender aesthetics and attitude. As in all treated areas, the most effective applications are delivered with precise injection techniques.

The most effective format of application and technique to this region has generated healthy debate. As in most facial regions, precision (i.e. targeting the recipient muscle with exactitude) will yield the most predictable responses. Understanding underlying facial muscle anatomy allows precision as to how much toxin is injected and where it is injected. The corrugator muscles lie deep to the insertion of the frontalis muscle in this region and just superficial to the periosteum of the supraorbital rim. Superficial injections (intradermal, subdermal/subcutaneous) will very likely equally (if not more) affect the frontalis muscle and will depend on diffusion to arrive at the corrugator muscles. Deeper injections (into the belly of this large muscle) will more accurately affect the corrugators in isolation. However, it should be mentioned that two of the authors (AC and JC) performed an objective study on 24 women with asymmetric medial eyebrows using an asymmetric injection technique as described above. On objective photographs taken at rest (Canfield system) there was no differential change in eyebrow height demonstrated. The techniques of one of the authors (SF) to this region is as follows (Fig. 24-12 and see DVD): The injector uses the non-dominant hand to stabilize the eyebrow between the thumb and forefinger and can also easily distract the medial eyebrow above the orbital rim. At the same time the injector can place the thumb into the supraorbital notch to protect against toxin migration posteriorly into the orbit. The injecting hand then orients the syringe at 90 degrees to the skin surface and with a swift motion attempts placement of the needle tip into the mid-aspect of the muscle in two places (the lateral and medial components of the corrugators). This maneuver is then repeated on the opposite side. Care is also taken to avoid unnecessarily puncturing periosteum (as happened with techniques described in the past, which aimed to pass the needle to the periosteum, then withdraw slightly to the muscle) as this can be a cause of headache and post-injection pain, probably due to periosteal inflammation.

Finally, this section would be incomplete if there were not a mention of our aesthetic goals that include what constitutes a satisfactory endpoint and outcome with effective dosing. Unfortunately, the concept of ‘immobility’ has become, in the mind of some consumers, synonymous with ‘effective’ treatment. Patients will return to your office to display their ability to ‘frown’ with the most unusual and noble efforts that produce the vaguest glimmer of a vertical frown line (Fig. 24-13). As in most situations, educating your patients on what they should expect and what constitutes an aesthetic satisfactory result that might not include immobility will avoid many phone calls and return visits and ultimately a happier and well-informed patient.

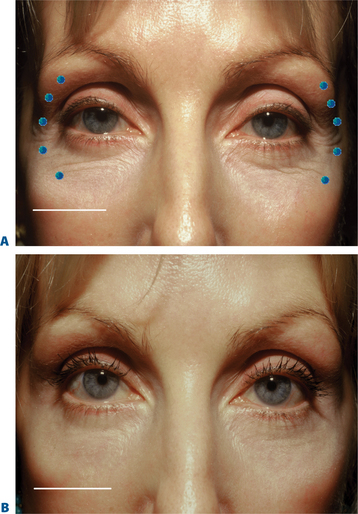

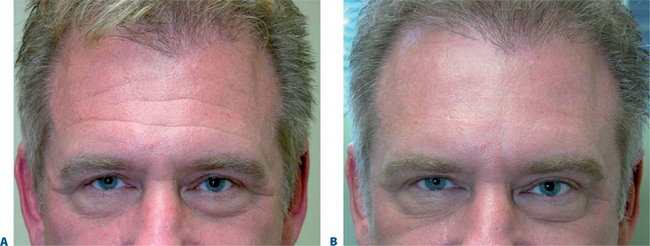

Horizontal forehead rhytides

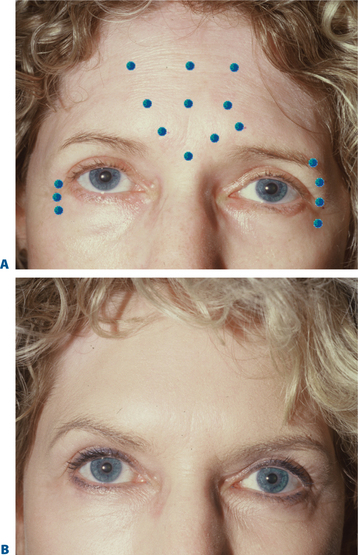

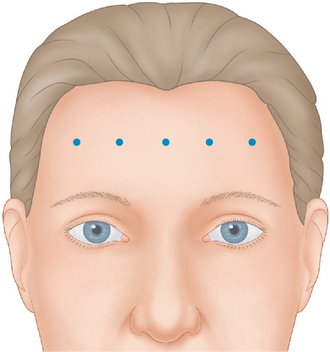

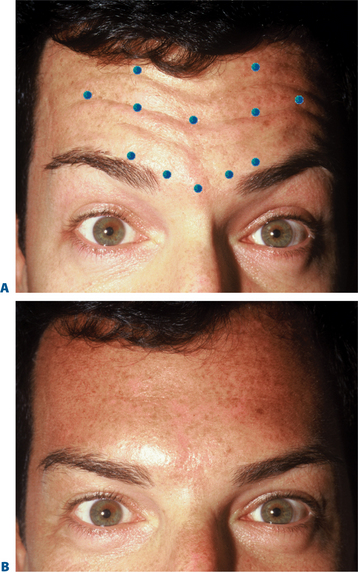

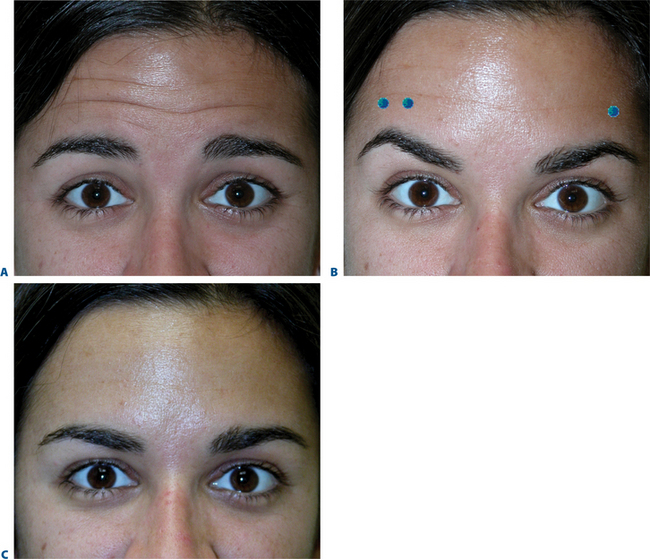

The frontalis is a large, quadrilateral muscle that originates in the galea aponeurotica. It inserts inferiorly into the procerus, orbicularis oculi, depressor supercilii muscles and anteriorly over the corrugator supercilii muscle, and terminates beneath the skin of the eye-brow. Although most figures (Fig. 24-4) depict the frontalis in two sections, it usually spans the forehead from one temporal fusion line to the other and may be thicker in certain portions of the forehead. The frontalis raises the eyebrows and skin over the root of the nose and also draws the scalp forward. Contraction of the frontalis primarily produces a series of horizontal forehead wrinkles and furrows. The most active portion of the frontalis muscle in most individuals is the 2 or 3 cm immediately above the brow. Activity in this portion produces horizontal rhytids that can appear as cephalad as the anterior hairline (Fig. 24-14). This finding is important when deciding at what locations BTX will be injected for a particular individual. Also, the effects of inducing brow ptosis will be greater if the lower portion of the forehead is injected (Fig. 24-15). In many individuals, a single row of treatment sites in the midforehead is effective in reducing or eliminating rhytids while preserving brow position (Fig. 24-16). Finally, as with most areas of the face, individual unique habitual animation and the desired aesthetic effects will dictate where the drug is applied. The lateral extent of the forehead injection sites will be influenced by a com-bination of aesthetic desires and the functional anatomy.

BTX-A injected across the forehead lessens undesirable horizontal forehead lines for a period of 4–6 months.30 Although treatment is individualized for each patient, in most individuals injections should be placed 2.5–3 cm above the brow proper to avoid brow ptosis or a lack of natural expressiveness. In general, narrow brows receive fewer injections and lower doses than broader higher brows. The exact site and dosage will depend on each individual presentation and the desired effects.

Dosing

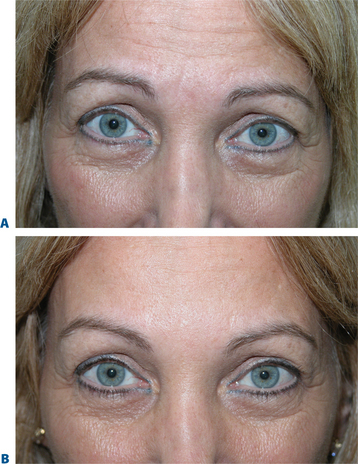

As in the glabella, prior research suggested that higher doses of BTX-A may be more effective than lower doses in the forehead. A randomized, double-blind, dose-ranging study examined 60 women injected with either 16, 32, or 48 U BTX-A in eight sites and found the greatest improvement and duration of response with 48 U.31 However, adverse effects (headache, eyelid swelling, and brow ptosis), though uncommon, were more frequently associated with the higher doses. For reasons less clear that might relate to muscle mass, the number of active neuromuscular junctions is less in the frontalis muscle,32 BTX-A effects in this region (for any combination of the postulated causes), usually last longer than any other facial area. Therefore despite a slight reduction in regional efficacy, lower dosages (and few injection sites) may allow for a more harmonious onset and dissipation of effects. Retained animation, reduction in the degree of induced brow ptosis and greater aesthetic benefits also result from more conservative dosing (Fig. 24-17). As mentioned, the frontalis is unusually ‘sensitive’ to even seemingly low doses of drug. The placement (whether intradermal, immediately subcutaneous, deep subcutaneous, or intramuscular) has less bearing on the result. Although a direct intramuscular injection usually gives the most effective treatment, the authors advocate a more superficial injection that helps avoid bleeding, bruising, significant pain, or hematoma that can ‘spoil’ an otherwise perfect application in selected individuals.

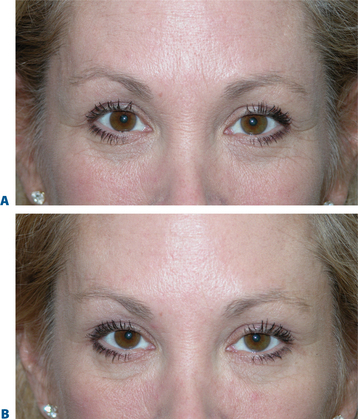

Brow lift and contouring

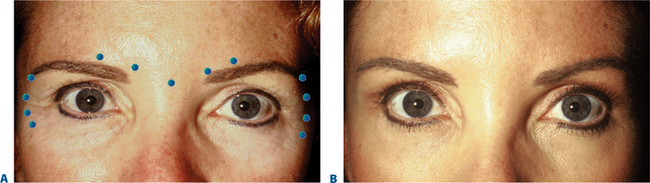

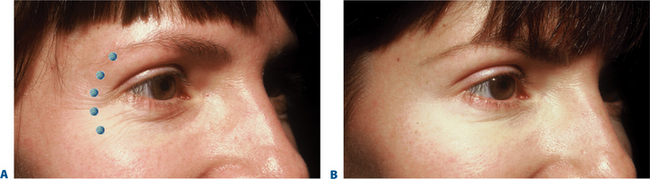

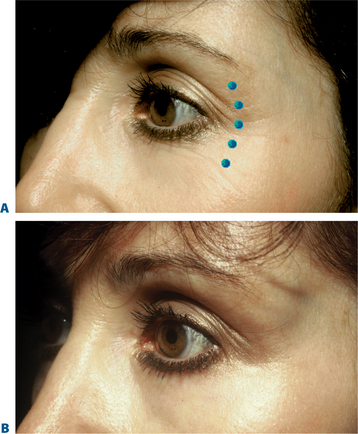

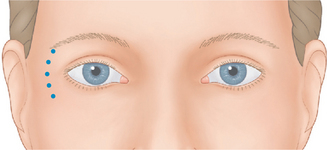

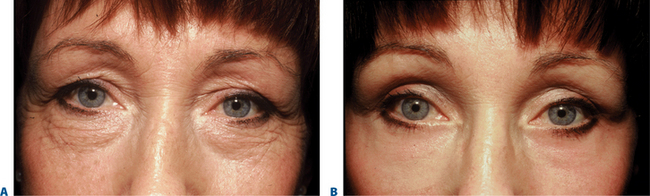

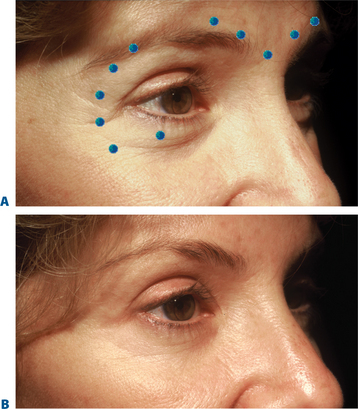

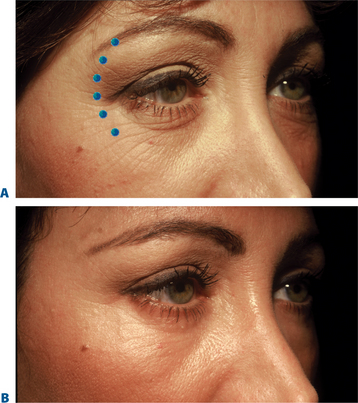

As previously mentioned, treating glabellar rhytides can also result in a pleasing brow lift. Adept clinicians can now predictably produce elevations in the medial, central, and temporal eyebrow. Varying treatments to the brow depressors have been shown to be effective in elevating the eyebrow through a host of techniques. Isolating treatment to the procerus, depressor supra-cilii, and lateral orbital orbicularis oculi muscle alone will elevate the brow but preserve its natural arc. Injecting 7 to 10 U BTX-A in the procerus at the midline, followed by one injection on each side (5 U) into the superolateral eyebrow at the temporal fusion line21 has been shown to be effective. This technique is especially useful in those individuals who exhibit brow ptosis and whose vertical glabellar frown lines are less of a concern (Fig. 24-18). This dramatically reduces the possibility of further brow depression (with any diffusion to the adjacent frontalis). By ignoring the variations in eyebrow shape presentation and the potential effects of treating the brow depressors in isolation, we fall short of delivering the optimum aesthetics (Fig. 24-19). Other techniques described demonstrate isolated injection of the lateral brow depressors13,14 by injection of 7–10 U into the superolateral orbicularis oculi at three sites below the lateral third of the brow, superior and lateral to the orbital rim, and produced significantly variable mid-pupillary and lateral brow elevations ranging from 1 to nearly 5 mm.13,14 The cause for such variability, while at first appearing confusing, might be more explainable than previously thought. Such variability has also been shown with surgical brow lifts, whereby the identical technique performed on various individuals can produce dramatically different results. The explanation most likely lies in the fact that precise application to the brow depressors can cause their dense chemo-denervation. The ‘lift’ ultimately will also depend on increased tone in frontalis.15 Significant brow elevation will be achieved after treatment to the brow depressors if the technique is precise. It is important to avoid injections ‘too high’ that may produce diffusion to the lateral frontalis (Fig. 24-20).

The potential effects and the ability to manipulate brow shape was a prelude to the recognition of the use of BTX for both the eradication of facial lines and as an agent for facial reshaping.4

Some patients experience eyebrow asymmetry, for which BTX-A has also been beneficial. There are many causes of eyebrow asymmetry, including facial nerve trauma following surgical brow lift or other surgically induced facial paralysis, ipsilateral eyelid ptosis, and asymmetric non-pathologic facial expression.9 BTX-A injections into the brow depressors on the lower brow side can reset the balance (Fig. 24-11). Extreme care must be taken when treating non-pathologic facial asymmetry, both for the treatment of rhytids and brow position. Patients may look aesthetically improved in repose, but they might appear unusual with even casual animation when mobility (i.e. of the forehead) is only seen on the untreated side (Fig. 24-21).

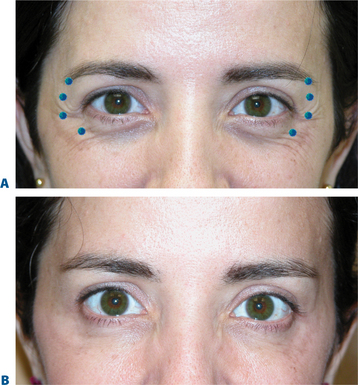

‘Crow’s feet’: treatment of the lateral periorbita and canthal region

Dosing

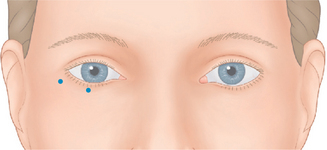

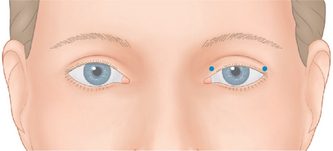

BTX-A injections of 12–15 U per side (in two to four injection sites) placed subdermally or intradermally relax the muscle of the lateral periorbita without completely inactivating the orbicularis oculi, which could affect both voluntary and involuntary eyelid function (discussed in ‘Complications with treatment to the periorbita’) and the ability to fully close the eye.7 Results usually last in the range of 3–6 months with few adverse effects (Fig. 24-22).

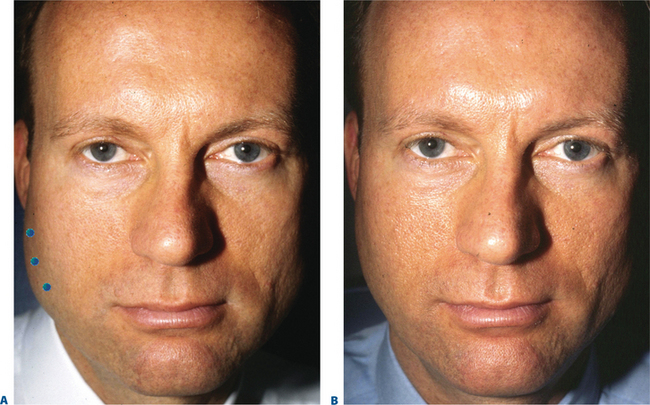

Although historically the use of BTX-A was mostly considered an effective tool for the eradication or improvement of facial rhytids, a higher level of understanding and vision of improved aesthetics and rejuvenation has revealed that it is equally if not more effective in the improvement of facial shape.4 Precise application of the drug, with strong consideration of both direct and indirect effects with the ability to augment results by applying the drug in a variety of ways in multiple facial regions in coordination, has facilitated the next level of aesthetic results. Similarly, the treatment of ‘crow’s feet’ in most situations should not be considered as an isolated therapy for canthal rhytids, rather a coordinated treatment for improvement of these lines and contouring of both the lateral eyebrow, midface, as well as improvement of lower eyelid lines, and orbicularis muscle hypertrophy (next section). The extended application of injection sites while treating the lateral periorbita will depend on the patient’s presentation and aesthetic desires and will vary from individual to individual (Fig. 24-23). The preferred plane of injection is immediately subdermal, whereby a significant wheal is observed with each dermal puncture (Fig. 24-24, and DVD). This can reduce bruising, bleeding and discomfort, but additionally places the toxin most distant (superficial plane) from the orbit, allowing for safe and effective treatment. The sites of treatment for the lateral periorbita and canthal rhytids are usually lateral to the lateral orbital rim (Figs 24-24 & 24-25).

Hypertrophic orbicularis

In some patients, particularly but not limited to individuals of Asian descent, the perceived size of the palpebral aperture diminishes noticeably while smiling, and they request ‘larger’ eyes as a component of aesthetic improvement. Other related phenomena include those who develop significant pretarsal ‘bulging’ in association with ‘smaller’ eyes (Fig. 24-26) from either chronic squinting (more common in those who either work or play outdoors in sunlight) or even those individuals who aesthetically desire a larger vertical palpebral aperture to improve appearance (see p. 317). Increasing the size of the palpebral aperture with carefully placed injections is another part of the new ‘art’ of BTX-A, and experience has shown that injections of 2 U into the lower pretarsal orbicularis will relax the palpebral aperture at rest and while smiling.7,15 One study describes the injection of 2 U subdermally, 3 mm inferior to the lower pretarsal orbicularis and, on one side only, three injections of 4 U placed 1.5 cm from the lateral canthus, each 1 cm apart, in 15 women.19 Mean palpebral aperture increase in 86% of patients was 1.8 mm at rest and 2.9 mm at full smile, with the most dramatic results seen in the Asian eye. However, it is important to select patients with good lid tone and proceed with particular caution in those who have had previous lower eyelid ablative resurfacing or transcutaneous blepharoplasties, so that the lateral canthal support is not affected. Better candidates for this application are typically younger females, without prior surgery, and no history or symptoms consistent with dry eye syndrome. At times, onset or worsening of lower eyelid/cheek festoons can also be seen in particular individuals with these treatments to the lower eyelid.33 This approach can also be used with caution in those individuals who experience and/or complain of worsening of the lower eyelid rhytids or ‘pretarsal bulge’ after traditional treatment to the lateral canthus.

As with all applications of BTX-A, the facial regions in proximity to the injection sites can experience secondary effects from toxin diffusion. Unwanted and exaggerated ‘over-elevation’ of the lateral eyebrow can result from toxin injected too high at the lateral commissure (Fig. 24-27). Midface ptosis can be the result of toxin being injected in the region of the zygomatic notch (Fig. 24-28). Diffusion effects can influence the cheek elevators (zygomaticus complex). In addition, those individuals with the early notation of ‘malar bags,’ lower eyelid lymphedema, or even lower eyelid bags can experience a worsening of the appearance of these conditions (even with treatments limited to the lateral canthus) (Fig. 24-29). Reduction of the effect of the lymphatic pump and reduction of muscle tone to the preseptal orbicularis muscle can lead to a peri-orbital edema that can last up to 4 weeks in rare individuals (Fig. 24-30).

Complications with treatments to the periorbita

Many patients will say, especially prior to their initial treatment, that the complication that they most fear is the development of upper eyelid ptosis. Although this is a relatively uncommon occurrence, it can be the cause of patients’ reluctance to undergo treatment. The effects of undesirable or unexpected soft tissue position changes are common (brow, lower eyelid, cheek, lip etc.). In most other facial areas treated however, no other complication is as obvious and disconcerting. The effect can occur from any of the periorbital regions discussed above including the forehead (Fig. 24-31), that is usually an unmasking of a compensated upper eyelid ptosis, or the glabellar (Fig. 24-32) or lateral canthal regions (Fig. 24-33). The cause in the later regions is usually due to diffusion effects that can occur from high dosing or improper placement. Fortunately, in many mild to moderate cases, the effects can be counteracted by the pharmacological effects of topical agents that causes the contraction of Müller’s muscle. Topical anti-histamine eye drops, such as naphazoline or antazoline, or drugs such as apraclonidine that also have a secondary effect of contraction of Müller’s muscle (without pupillary dilation) all can be effective in improving the upper eyelid posture if such an effect is experienced (Fig. 24-32B). Adrenergic agents such as neosynephrine should be avoided because of secondary cardiac effects. The persistence and longevity of the occurrence of upper eyelid ptosis is, as always, dose-dependent (i.e. a large dose to the levator muscle can have a rather rapid onset and can persist for months). Additionally, if dosages to the upper eyelid and orbit are sufficiently large the effect of these kinds of remedy therapy are less if at all effective, especially if the lid ptosis is profound.

A common, but more easily treated undesirable effect is the over-elevated lateral eyebrow with treatment to the lateral canthus commonly called the ‘Mr Spock’ eyebrow (Fig. 24-27). This can most often be predicted if one evaluates how the patient animates, even during the consultation and examination. For instance, individuals who furrow clearly to the lateral forehead will more often experience this over-elevation if the brow depressors are effectively weakened and the forehead is also treated less effectively (lack of concurrent treatment to the lateral forehead). Treatment is also easily afforded in this situation by treating the previously untreated forehead area in the appropriate manner (Fig. 24-34). Interestingly, in many cases, these situations of over-elevation of the lateral eyebrow will ‘settle down’ even without treatment, possibly due to some sort of adaptation that is often observed yet poorly understood. Finally, on a related issue, these secondary adaptational effects (i.e. enhanced ‘bunny lines’ after the treatment of the glabella in isolation, over-elevated eyebrow with treatment of the lateral canthus etc.) that have been called ‘recruitment’ or ‘complications’ can be avoided by accurate pretreatment assessment. Predicting what areas may ‘recruit’ becomes part of the art of planning the most effective and aesthetic results.

Treatment of mild upper eyelid ptosis and lid malposition and asymmetry

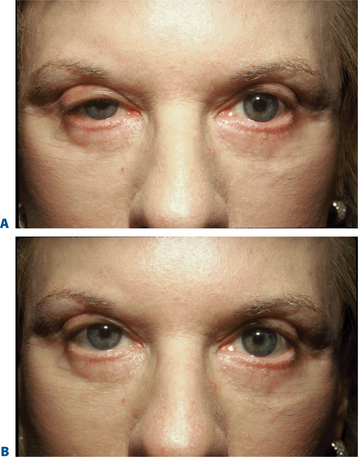

The physiologic mechanisms whereby eyelid fissure symmetry is achieved in the blepharospastic patient (Fig. 24-1) is by reducing the musculospastic effect of the protagonist (orbicularis muscle) while allowing the antagonist (Müller’s muscle and the levator muscle) to stand relatively less opposed. The result is a precise reduction or elimination of focal blepharospasm with the secondary effect of enhancing the vertical palpebral aperture.

Often those patients with even mild true upper eyelid ptosis, induced by unilateral chronic facial spasm, appear to have complete resolution of the upper eyelid malposition (Fig. 24-2). A similar phenomenon exists in the lower eyelid; patients who have been treated for lower eyelid lines, orbicularis muscle hypertrophy, or spastic involutional entropion with focal injections of Botox to the various regions of the lower eyelid (Fig. 24-26) commonly exhibit a variable degree of lower eyelid retraction and scleral show. As it is apparent that the upper eyelid position can be affected by manipulation of the protagonistic/antagonistic effects of the lid elevators and depressors in conditions of blepharospasm, it stands to reason that upper (and lower) eyelid position can also be influenced even in the non-spastic state. This hypothesis prompted further study for the use of botulinum toxin type A for aesthetic improvement of upper and lower eyelid position for a variety of conditions.15

Dosing

Lower dosages, in the order of magnitude of 1–2 units per injection site are typical for these applications. Higher dosages (as in other facial regions where function may be affected such as the lips) can cause significant morbidity such as exposure keratopathy, or epiphora, as well as lack of aesthetic improvement. For mild to moderate upper eyelid ptosis, the starting dosages are usually around 1 unit applied to the pre-tarsal orbicularis (in the subdermal plane) at the extreme medial and lateral aspect (Fig. 24-35). Results can be dramatic (Fig. 24-36). Due to lower dosing, the effects are less long-lasting and usually are in the 2–3 month range.

Figure 24-35 Mild to moderate upper eyelid ptosis can be treated with ‘low-dose’ BTX to the pretarsal orbicularis oculi as shown.

Upper eyelid position has been shown to be influenced by manipulation of the eyebrow in several ways.15 As shown previously (Fig. 24-31), those individuals with compensated upper eyelid ptosis (i.e. those patients who raise their eyebrow to elevate the upper eyelid to the slightest degree when a mild upper lid ptosis exists) will negate this effect if Botox is used to counter the associated forehead furrows. Similarly, a small subset of individuals with mild to moderate upper eyelid retraction (interestingly, these patients commonly wear vision corrective contact lenses) who demonstrate this enhancement of the vertical palpebral aperture and do not raise their forehead for this effect, will show a reduction of the upper eyelid retraction when Botox is applied to raise the eyebrow (Fig. 24-37).

Treatment to the lower eyelid can be applied to asymmetries that result from congenital effects, aging changes, prior surgery, stroke, and a host of other regions including bilateral lower eyelid treatment to ‘enlarge’ the eyes (enhance the vertical dimension of the palpebral aperture). Higher dosages to the lower eyelid region should also be avoided and the usual starting dose is 1–2 units per injection site. The location will depend on the effects desired (Figs 24-38 to 24-40).

Treatment of the mid- and lower face

Clinicians must take care when injecting BTX-A into the mid- and lower face; incorrect placement of the toxin can have devastating effect (albeit temporary) on function and expression, particularly in the perioral region. Attempts at treatment of the proximal nasolabial fold and also to reduce the ‘gummy smile’ (discussed later) can, at times, achieve significant improvement for the appropriate patient. The nasolabial fold, for instance, can be completely effaced with BTX. This unfortunately can mimic the effects seen after facial paralysis or weakness (i.e. Bell’s palsy or stroke). Any attempts to significantly improve the nasolabial fold by chemodenervation alone will usually yield such a ‘paralytic’ appearance. Prior experience with upper face injections and a thorough understanding of anatomy and vasculature are strongly recommended (Fig. 24-28).

Nasalis ‘bunny lines’

Frequent contraction of the upper nasalis, which runs from the bony dorsum of the nose inferiorly, contributes to the development of fanning, radial rhytides obliquely across the radix of the nose called ‘bunny lines.’ Treatment allows the underlying mimetic musculature to relax, softening the lines. Inject anterior to the nasojugal groove on the lateral wall of the nose and well above the angular vein, and massage gently after injection to help diffuse the toxin. The lower nasalis fibers drape over the lateral nasal ala and can lead to repeated nasal flare, in which nostrils dilate involuntarily in social situations and give patients the embarrassing appearance of a race horse. Injection into the lower nasalis fibers will weaken this involuntary action (Fig. 24-41). Higher dose injections (5 units per side) or those administered caudal to these locations may affect the levator labii superioris aleque nasi and can be effective in further reducing the ‘bunny lines.’ Higher dosages to this region injected with precision can reduce the ‘gummy smile’ and soften the proximal nasolabial fold in the appropriate patient. Care should be taken to avoid or reduce the effects to the primary lip elevators (i.e. levator labii superioris) in most situations.

Lower face

Perioral lip rhytides (‘smokers’ lines’)

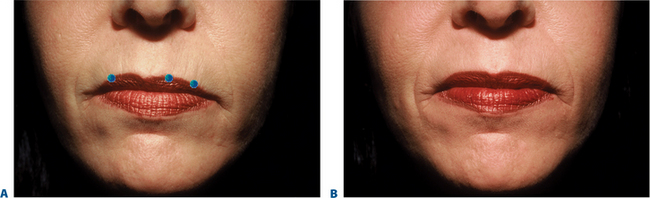

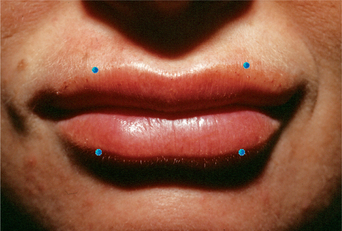

The orbicularis oris is the sphincter-like muscle that encircles the mouth, lying between the skin and mucous membranes of the lips and extending upward to the nose and down to the region between the lower lip and chin. Sometimes called the ‘kissing’ muscle, it causes the lips to close and pucker. Overactive orbicularis oris causes vertical perioral rhytides (which are referred to as smokers’ or lipstick lines but often have numerous causes, such as heredity, photodamage, playing musical instruments that require embouchure, whistling, and other personal habits). Very small amounts of BTX-A (1 to 2 U per lip quadrant) are usually sufficient to result in localized microparesis of the orbicularis oris and can be used as a primary agent for the treatment of dynamic lip rhytids3,4,9–11,30 (Fig. 24-42). Similar to treatment in the other facial areas, at these dosages the dynamic component is mostly satisfactorily affected, while deep static rhytids may have at best a modest improvement. In addition, the lower dosages are necessary to avoid lip dysfunction, while typically effects last in the range of 6–8 weeks. This application (using lower dosing) is especially useful when used adjunctively with a soft-tissue augmenting agent, and can greatly improve persistence of the filling agent by reducing the dynamic local activity that may be responsible for dissolution of the injected implant (Fig. 24-43). Symmetric injections (unless otherwise indicated) and careful placement of the injection sites to balance either side of the columella or the lateral nasal ala will help alleviate difficulty with post-injection asymmetry, lip proprioception, and aesthetics experienced with some patients. Patients who play a wind instrument or who are professional singers/speakers may not be ideal candidates.

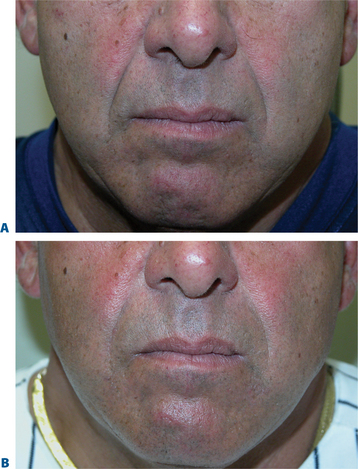

Midfacial asymmetry

Although midfacial asymmetry may have multiple etiologies, asymmetry with innervational or muscular causes can be minimized or alleviated with BTX-A. In hemifacial spasm, for example, repeated clonic and tonic movements draw the facial midline toward the hyperfunctional side. BTX-A injections into the hyperfunctional zygomaticus, risorius, and masseter relax the muscles and allow the face to fall back into a centered position at rest. Likewise, hypofunctional asymmetry, such as Bell’s palsy, can be alleviated by small injections of 1–2 U into the zygomaticus, risorius, and orbicularis, and 5–10 U in the masseter on the normofunctional side.8 In patients with asymmetric jaw movements, intraoral injections of 10–15 U BTX-A in the internal pterygoid on the hyperfunctional side will relax the jaw and relieve discomfort. Surgical cutting or trauma to the orbicularis oris or the risorius muscle can result in an off-centered mouth caused by the unopposed action of the partner muscles in the normally innervated side. Correction can be achieved by treatment of the risorius immediately lateral to the corner of the mouth on the normally innervated side. In patients with congenital or acquired unilateral weakness, who cannot depress the corner of one side of the mouth, BTX-A injected into the partner depressor anguli oris will restore functional balance.

Depressor anguli oris

The depressor anguli oris (DAO) extends inferiorly from the modiolus to attach into the inferior margin of the mandible on the lateral aspect of the chin. DAO contraction causes a downward turn to the corner of the mouth, resulting in a negative, bitter appearance. Repetitive contraction over many years likely has a dramatic influence on volume loss to this region and the appearance of ‘perimental hollows’ and ‘jowling.’ Since direct injection of the DAO can cause intolerable paresis of the depressor labii, BTX-A injections are placed instead at the level of the mandible but at its posterior margin, close to the anterior margin of the masseter (easily felt when patients are directed to clench their teeth). The aim of treatment is to weaken, not paralyze, the DAO; doses of 3–5 U are usually sufficient to achieve the desired result (Fig. 24-44). In addition, the simultaneous injection of the DAO with injectable soft tissue augmentation to this region will enhance the result.

Mental crease

The mental crease can be softened by injecting 3–5 U BTX-A into the mentalis just anterior to the mentum (Fig. 24-45). Injection higher at the level of the mental crease will also weaken the lower lip depressors and orbicularis oris, causing serious perioral weakness lasting 6 months or more. As in the perioral area, weakening, rather than paralysis, is the aim of treatment.

Peau d’orange chin

A dimpled or ‘peau d’orange’ appearance in the aging chin occurs when a loss of subcutaneous fat and dermal collagen unmasks the mentalis and depressor labii muscle attachments. A combination of BTX-A into the mentalis plus soft-tissue augmentation leads to optimal results, although some patients fare well with BTX-A alone (Figs 24-44, 24-45).

Coordinated treatment of the mouth corners and chin

The opposing actions off the DAO (downward) and mentalis (upward) cause permanent downward angulation of the lateral corners of the mouth. When treating mouth frown with BTX-A, it is important to remember that treatment of a single muscle may positively or negatively affect adjacent muscles. Weakening the DAO or mentalis alone, while appropriate in some individuals, may be associated with unacceptable side effects in others. However, lower doses of BTX-A injected simultaneously into both muscles (3 U into each DAO and mentalis, for a total of 12 U) results in a synergistic and subtle effect that is safe and does not interfere with elocution or pursing of the lips (Fig. 24-46).

Lower facial asymmetry

Some patients experience surgical or traumatic cutting of the orbicularis oris or risorius, resulting in decentration of the mouth from the unopposed action of the partner muscles in the normally innervated side. BTX-A injected in the overdynamic risorius, immediately lateral to the lateral corner of the mouth will help to recenter the mouth when the face is in repose. Patients may have congenital or acquired (even iatrogenic) weakness of the DAO, resulting in inability to depress the corner of one side of the mouth; chemodenervation of the contralateral synergistic muscle will restore functional and aesthetic symmetry (Fig. 24-47).

Masseteric hypertrophy

Contouring the lateral muscular jaw prominence – a relatively common aesthetic procedure especially among Asian patients – is yet another use for BTX-A. Park et al injected 25–30 U BTX-A per side in five to six sites evenly at the prominent portions of the mandibular angle in 45 Asian patients for aesthetic improvement and found a gradual reduction in masseter thickness during the first 3 months following injection.34 The average change in masseter thickness, 1.5–2.9 mm, was equivalent to 17 to 19 percent of the original muscle thickness, as measured by ultrasound and computerized tomography. The response lasted 6–7 months before the muscle thickness retreated to its initial size; at 10 months, 36 patients expressed satisfaction with the results. Masseter hypertrophy is also a common byproduct of bruxism. This application in these individuals is not only an aesthetic enhancement, but also a dramatically effective cure for the sometimes significant focal pain associated with these disorders (Fig. 24-48). Local side effects, including mastication difficulty, transient muscle pain, and verbal difficulty during speech, were uncommon.

Cervical indications

Vertical platysmal bands

When cervical skin loses its elasticity, the anatomy of the submental space changes: more submental fat becomes visible, and the platysma separates into two diverging vertical bands that tighten and become prominent during speech or other animation. Early banding can be seen in younger individuals that may reflect a hyperdynamic nature of the platysma. BTX-A injections can soften vertical platysmal bands in some patients27,35; however, careful patient selection of those with obvious platysmal bands, good cervical skin elasticity, and minimal fat descent, is essential.36 Younger patients with significant banding may require larger dosages in lieu of the hyperdynamic activity that is able to distract the cervical soft tissue, despite adequate skin elasticity and tone. On the other hand, in the elderly who exhibit a significant degree of descent and jowl formation, treatment with BTX-A may be entirely ineffective or actually worsen the appearance of the bands. Used as an adjunct to rhytidectomy, BTX-A can reduce the residual muscular banding that becomes apparent in the postoperative phase. In addition, some patients may prefer to use BTX as a kind of ‘rehearsal’ for the surgical alternative. Also, BTX-A into the platysma muscle may reduce the undesirable inferior pull of the platysma muscle on the facelift incision, thus resulting in a thinner and finer scar.37

Since the platysma is external to the muscles of deglutition and neck flexion, large doses of BTX-A (i.e. 75 or 100+ U) have been known to cause profound dysphagia,30 and must be used cautiously. Decreased phonation, difficulty with head posture, and worsening of dry mouth have also been reported with ‘over-dosing.’ Injecting 5 U with as few as three sites for each band (with sites that are 1–1.5 cm apart) and no more than 25–30 U over multiple sites per treatment session is typical. The safest effective plane is more superficial and the least likely to induce unwanted effects. It is far better to under-treat; additional ‘touch-up’ treatments can always be given if necessary during a subsequent treatment session (Fig. 24-49).

Adjunctive use in facial aesthetic enhancement

The adjunctive use of BTX-A with a host of other methods used for aesthetic facial enhancement has demonstrated a clear synergy when the appropriate combination of therapeutic modalities are applied. Improved and longer lasting results with a variety of energy/laser applications, injectable soft tissue agents, wound healing, brow lifts, canthopexy/plasty, suture suspension techniques, have been demonstrated3,9–11,38 while this is only a shortlist of the potential adjunctive benefits (Figs 24-50 to 24-54).

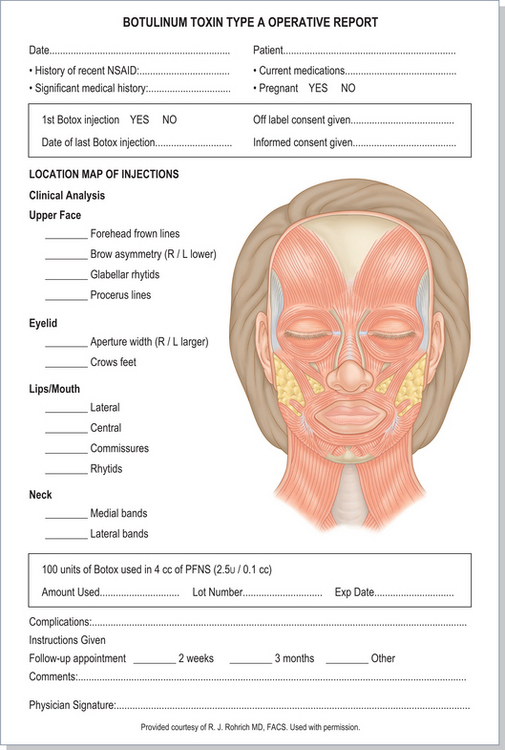

Documentation of pretreatment status and procedural reporting

A clear diagrammatic operative note is also essential for both an explanation and documentation of treatment details and for your own record of treatment that might be amended in future sessions based on response (Figs 24-55, 24-56). This record should include lot number, dilution, site, number of units per site, and any other notations including unusual blemishes, bleeding, etc.

Figure 24-56 An operative report might contain a drawing as shown here or in Figure 24-55, and can be more detailed as shown here. A brief history is contained here that is a review of medical history and medication that might have changed from the prior visits, as well as other information indicating the specific treatment and follow-up, lot number, total dose, etc.

Original figure courtesy of RJ Rohrich, MD, FACS. Used with permission.

Conclusion

As with many discoveries in science and medicine, it is often the accidental discoveries that have the most profound effects. Our collective experiences with BTX have not only expanded the applications of this useful primary tool for facial rejuvenation and a vital adjunctive agent to improve other methods, but has also enlightened us to the complicated causes of facial aging and the explanation for failure of various previous treatment methods. Although initial applications were used primarily for the improvement or correction of facial rhytids it has been shown to be useful in the enhancement of facial shape. The greatest aesthetic results with this agent are achieved through a higher level of understanding of the multitude of potential beneficial effects, an accurate and comprehensive patient assessment, detailed knowledge of facial anatomy, and a precise application to achieve maximal benefits while avoiding complications.

1 Carruthers JD, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:17-21.

2 Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:1044-1099.

3 Fagien S. Botox for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows: Adjunctive use in facial aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:40S-52S.

4 Fagien S. Botulinum toxin type A for facial aesthetic enhancement: role in facial shaping. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(Suppl.):6S.

5 Carruthers JDA, Stubbs HA. Botulinum toxin for benign essential blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm and age-related lower eyelid entropion. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14:25-42.

6 Fagien S: Cosmetic improvement of dyskinetic eyelid and facial asymmetry with botulinum toxin type A. Abstract submitted to the annual meeting of the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, Summer, 1991.

7 Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Botulinum toxin type A: History and current cosmetic use in the upper face. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:71-84.

8 Carruthers JDA, Carruthers JA. Botulinum toxin in clinical ophthalmology. Can Ophthalmol. 1996;31:389-400.

9 Fagien S, Brandt FS. Primary and adjunctive use of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) in facial aesthetic surgery: Beyond the glabella. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:127-148.

10 Fagien S. Extended use of botulinum toxin A in facial aesthetic surgery. Aesthet Surg Journal May/June;. 1998;18:215-219.

11 Fagien S. Treatment of hyperkinetic facial lines with botulinum toxin. In: Putterman AM, editor. Cosmetic Oculoplastic Surgery: Eyelid, Forehead, and Facial Techniques. Third Edition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1998:377-388. Chapter 33

12 Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Dose dilution and duration of effect of botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) for the treatment of glabellar rhytids. Presented at the American Academy of Dermatology 2002 Winter Meeting, 2002 February 22-27, New Orleans, LA.

13 Ahn MS, Catten M, Maas CS. Temporal brow lift using botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2000;105:1129-1135.

14 Fagien S. Temporal browlift using botulinum toxin A: an update by Kim EJ, Maas CS. Plast Reconstr Surg [Discussion]. 2003;112(Suppl.):105S.

15 Fagien S. Temporary management of upper lid ptosis, lid malposition, and eyelid fissure asymmetry with botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1892.

16 Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Fagien S, Stuzin JM. Botulinum toxin: expanding role in medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(Suppl.):1S.

17 Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Fagien S, Stuzin JM. The cosmetic use of botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(Suppl.):177S.

18 Carruthers J, Fagien S, Matarasso SL. Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(Suppl.):1S.

19 Flynn TC, Carruthers JA, Carruthers JA. Botulinum-A toxin treatment of the lower eyelid improves infraorbital rhytides and widens the eye. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:703-708.

20 Huang W, Rogachefsky AS, Foster JA. Brow lift with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:55-60.

21 Huilgol SC, Carruthers A, Carruthers JDA. Raising eyebrows with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2000;25:373-376.

22 Carruthers JA, Lowe NJ, Menter MA, et al. A multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:840-849.

23 Carruthers JA, Lowe NJ, Menter MA, et al. A multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in treatment of glabellar lines. J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(Suppl.):5S.

24 Fagien S. Double blind, placebo-controlled: study of the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type a in patients with glabellar lines by Carruthers JD, Lowe NJ, Menter A, Gibson J, Eadie N. Plast Reconstr Surg [Discussion]. 2003;112(Suppl.):31S.

25 Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Glabella BTX-A injection and eyebrow height: A further photographic analysis. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, March 21-26 2003, San Francisco, CA.

26 Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Said S: Dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Presented at the 20th World Congress of Dermatology, July 1-5 2002, Paris, France.

27 Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) in the treatment of glabellar rhytids: An objective analysis of treatment response. Presented at the American Academy of Dermatology 2002 Winter Meeting, February 22-27 2002, New Orleans, LA.

28 Fagien S: Multiple causes for brow lift effect from glabellar injections. The First Annual Meeting of the National Education Faculty Training sponsored by Allergan, Inc. The Westin Hotel, Denver, Colorado. July 26, 2003.

29 Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Botulinum toxin type A for treating glabellar lines in men: A dose-ranging study. Presented at the 20th World Congress of Dermatology, July 1-5 2002, Paris, France.

30 Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Cohen J. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type A in female subjects with horizontal forehead rhytides. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:461-467.

31 Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Cohen J: Dose dependence, duration of response and efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of horizontal forehead rhytids. Presented at the American Academy of Dermatology 2002 Winter Meeting, February 22-27, 2002, New Orleans, LA.

32 Happak W, Liu J, Burggasser G, et al. Human facial muscles: Dimensions, motor endplate distribution, and presence of muscle fibers with multiple motor endplates. Anat Rec. 1997;249:276-284.

33 Goldman MP. Festoon formation after infraorbital botulinum-A toxin: A case report. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:560-561.

34 Park MY, Ahn KY, Jung DS. Botulinum toxin type A treatment for contouring of the lower face. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:477-478.

35 Matarasso A, Matarasso SL, Brandt FS, Bellman B. Botulinum A exotoxin for the management of platysma bands. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:643-652.

36 Fagien S. Botulinum A Exotoxin for the Management of Platysma Bands by Matarasso A, Matarasso SL, Brandt FS, Bellman B. Plast Reconst Surg [Discussion]. 1999;103:653.

37 Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Using Botulinum Toxins Cosmetically. London & New York: Martin Dunitz, Taylor & Francis Group, 2003;59.

38 Carruthers JDA, Carruthers A. The adjunctive use of BOTOX. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(11):1244-1247.