137 Exophthalmos

Salient features

Examination

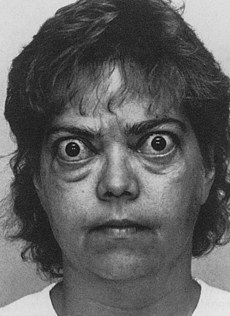

• Prominent eyeballs (Fig. 137.1).

• Look at the patient’s eyes from behind and above for proptosis.

• Comment on lid retraction (the sclera above the upper limbus of the cornea will be seen); this is Dalrymple’s sign (Fig. 137.2).

• Comment on the sclera visible between the lower eyelid and the lower limbus of the cornea (i.e. comment on the exophthalmos). Most patients have bilateral exophthalmos with unilateral prominence.

• Check for lid lag (ask the patient to follow your finger and then move it along the arc of a circle from a point above the patient’s head to a point below the nose—the movement of the lid lags behind that of the globe); this is von Graefe’s sign. Voluntary staring can result in a false lid lag, and the patient must be suitably relaxed before eliciting this sign.

• Check for extraocular movements and comment on the cornea.

Advanced-level questions

What eye signs of thyroid disease do you know?

Werner’s mnemonic, NO SPECS (J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1977;44:203–4):

What would you recommend if a patient with unilateral exophthalmos is clinically and biochemically euthyroid?

What are the components of the clinical activity score for Graves’ opthalmopathy?

The positive predictive value for therapeutic response for a CAS of 3/7 (or 4/10) is 80%, whereas the negative predictive value is 64%. Although the CAS is extremely useful for assessment of activity, its binary scoring makes it much less useful for monitoring change over time. The European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) atlas is one tool for assessment and is freely available at www.eugogo.org

How would you manage a patient with Graves’ ophthalmopathy?

The single most important aspect is a close liaison between the physician and the ophthalmologist.

Severe Graves’ disease and visual loss. This should be treated immediately with high doses of corticosteroids, orbital irradiation and plasma exchange as an adjunct. If there is no improvement within 72–96 h, orbital nerve decompression by surgical removal of the floor and medial wall of the orbit is necessary.

Moderate ophthalmopathy. This improves substantially in 2–3 years in most patients. In the interim the patient is treated symptomatically:

Mild ophthalmopathy. This can be rectified by cosmetic eyelid surgery. It is important to remember that patients can be distressed by their appearance. During the early acute phase, patients will have considerable symptomatic relief from the following measures:

What is the role of radioiodine in thyroid eye disease?

• Since radioiodine treatment carries a substantial risk of exacerbating pre-existing thyroid eye disease, it should be avoided as far as possible in patients with active or severe ophthalmopathy, in whom medical therapy with a thionamide drug such as carbimazole is preferable. Radioiodine may be used in patients with mild eye disease but adjuvant oral corticosteriods should be prescribed (N Engl J Med 1998;338:73–8).

• Patients without clinical evidence of thyroid disease have a small risk of developing ophthalmopathy and a very low risk of developing severe eye disease. It is prudent to warn all patients of this complication, but the risks do not justify denying most patients the benefits of definitive treatment with radioiodine when indicated. In addition, the risks do not justify the routine use of corticosteroids in patients without ophthalmopathy (BMJ 1999;319:68–9).

• Smoking, raised serum T3 and uncorrected hypothyroidism are also factors that can exacerbate thyroid eye disease. Therefore, to reduce the risk of thyroid eye disease, patients should be encouraged to stop smoking, be rendered euthyroid with a thionamide before radioiodine, and be monitored closely to detect and treat early hypothyroidism or persistent hyperthyroidism.

Mention the less important eponyms related to thyroid eye disease

• Infrequent blinking: Stellwag’s sign

• Tremor of closed eyelids: Rosenbach’s sign

• Difficulty in everting upper eyelid: Gifford’s sign

• Absence of wrinkling of forehead on sudden upward gaze: Joffroy’s sign

• Impaired convergence of the eyes: Möbius’ sign

• Weakness of at least one of the extraocular muscles: Ballet’s sign

• Paralysis of extraocular muscles: Jendrassik’s sign

• Poor fixation on lateral gaze: Suker’s sign

• Dilatation of pupil with weak epinephrine solution: Loewi’s sign

• Jerky pupillary contraction to consensual light: Cowen’s sign

• Increased pigmentation of the margins of eyelids: Jellinek’s sign

• Upper lid resistance on downward traction: Grove’s sign

• Abnormal fullness of the eyelid: Enroth’s sign

• Unequal pupillary dilatation: Knie’s sign

• When the eyeball is turned downwards, there is arrest of the descent of the lid, spasm and continued descent: Boston’s sign

• When the clinician places his or her hand on a level with the patient’s eyes and then lifts it higher, the patient’s upper lids spring up more quickly than the eyeball: Kocher’s sign.