Chapter 6

Exercise Stress Testing

1. What is the purpose of exercise stress testing (EST) and how can a patient exercise during stress testing?

2. What is the difference between a maximal and submaximal EST?

Maximal EST or symptoms-limited EST is the preferred means to perform an EST and attempts to achieve the maximal tolerated exercise capacity of the patient. It is terminated based on patient symptoms (e.g., fatigue, angina, shortness of breath); an abnormal ECG (e.g., significant ST depression or elevation, arrhythmias); or an abnormal hemodynamic response (e.g., abnormal blood pressure response). A goal of maximal EST is to achieve a heart rate response of at least 85% of the maximal predicted heart rate (see Question 9).

Maximal EST or symptoms-limited EST is the preferred means to perform an EST and attempts to achieve the maximal tolerated exercise capacity of the patient. It is terminated based on patient symptoms (e.g., fatigue, angina, shortness of breath); an abnormal ECG (e.g., significant ST depression or elevation, arrhythmias); or an abnormal hemodynamic response (e.g., abnormal blood pressure response). A goal of maximal EST is to achieve a heart rate response of at least 85% of the maximal predicted heart rate (see Question 9).

Submaximal EST is performed when the goal is lower than the individual maximal exercise capacity. Reasonable targets are 70% of the maximal predicted heart rate, 120 beats per minute, or 5 to 6 metabolic equivalents (METs) of exercise capacity (see Question 12). Submaximal EST is used early after myocardial infarction (see Question 8).

Submaximal EST is performed when the goal is lower than the individual maximal exercise capacity. Reasonable targets are 70% of the maximal predicted heart rate, 120 beats per minute, or 5 to 6 metabolic equivalents (METs) of exercise capacity (see Question 12). Submaximal EST is used early after myocardial infarction (see Question 8).

3. How helpful is an EST in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease?

4. What are the risks associated with EST?

When supervised by an adequately trained physician, the risks are very low. In the general population, the morbidity is less than 0.05% and the mortality is less than 0.01%. A survey of 151,944 patients 4 weeks after a myocardial infarction showed slight increased mortality and morbidity of 0.03% and 0.09%, respectively. According to the national survey of EST facilities, myocardial infarction and death can be expected in 1 per 2,500 tests.

5. What are the indications for EST?

The most common indications for EST, according to the current American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, are summarized in Box 6-1. When considering ordering an EST, three fundamental factors need to be considered to have an optimal diagnostic test: a normal baseline ECG, a patient who is able to exercise to complete the exercise protocol planned, and an appropriate indication for EST.

6. Should asymptomatic patients undergo ESTs?

7. What are contraindications for EST?

The contraindications for EST according to the current ACC/AHA guidelines are summarized in Box 6-2.

8. What parameters are monitored during an EST?

During EST, three parameters are monitored and reported: the clinical response of the patient to exercise (e.g., shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, angina pectoris, Borg Scale score), the hemodynamic response (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure response), and the ECG changes that occur during exercise and the recovery phase of EST.

9. What is an adequate heart rate to elicit an ischemic response?

10. How do I calculate the predicted maximal heart rate?

The maximal predicted heart rate can be estimated with the following formula:

12. What is a metabolic equivalent (MET)?

METs are defined as the caloric consumption of an active individual compared with their resting basal metabolic rate. They are used during EST as an estimate of functional capacity. One MET is defined as 1 kilocalorie per kilogram per hour and is the caloric consumption of a person while at complete rest (i.e., 2 METs will correspond to an activity that is twice the resting metabolic rate). Activities of 2 to 4 METs (light walking, doing household chores, etc.) are considered light, whereas running or climbing can yield 10 or more METs. A functional capacity below 5 METs during treadmill EST is associated with a worse prognosis, whereas higher METs during exercise are associated with better outcomes. Patients who can perform more than 10 METs during EST usually have a good prognosis regardless of their coronary anatomy.

13. What is considered a hypertensive response to exercise?

14. Can I order an EST in a patient taking beta-blockers?

15. What baseline ECG findings interfere with the interpretation of an EST?

16. When can an EST be performed after an acute myocardial infarction?

17. Are the patient’s sex and age considerations for EST?

18. When is an EST interpreted as positive?

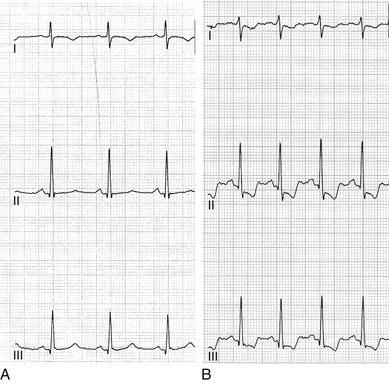

It is important for the physician supervising the test to consider the individual pretest probability of the patient undergoing EST to have underlying coronary artery disease while interpreting the results, and to consider not only the ECG response but all the information provided by the test, including functional capacity, hemodynamic response, and symptoms during exercise. ECG changes consisting of greater than or equal to 1 mm of horizontal or down-sloping ST-segment depression or elevation at least 60 to 80 msec after the end of the QRS complex during EST in three consecutive beats are considered a positive ECG response for myocardial ischemia (Fig. 6-1). Also, the occurrence of angina is important, particularly if it forces early termination of the test. Abnormalities in exercise capacity, blood pressure, and heart rate response to exercise are also important to be considered when reporting the results of EST.

Figure 6-1 Abnormal electrocardiographic (ECG) response to exercise in a patient found to have a severe stenosis of the right coronary artery. A, Normal baseline ECG. B, Abnormal ECG response at peak exercise with marked downsloping ST depression and T-wave inversion.

19. What are the indications to terminate an EST?

20. What is a cardiopulmonary EST and what are the indications of this diagnostic test?

During a cardiopulmonary EST, the patient’s ventilatory gas exchange is monitored in a closed circuit and measurements of gas exchange are obtained during exercise (i.e., oxygen uptake, carbon dioxide output, anaerobic threshold), in addition to the information provided during routine EST. Cardiopulmonary EST is indicated to differentiate cardiac versus pulmonary causes of exercise-induced dyspnea or impaired exercise capacity. It is also used in the follow-up of patients with heart failure or who are being considered for heart transplantation.

21. Can I localize which coronary artery is affected using the ECG during EST?

22. Can one obtain a stress test if a patient cannot exercise?

23. How often should an EST be repeated?

Repeating an EST without a specific clinical indication at any interval has not been shown to improve risk stratification or prognosis in patients with or without known coronary artery disease, and is discouraged. An EST can be repeated when a significant change in the patient’s cardiovascular status is suspected, or according to the appropriate indications as noted in Box 6-1. In patients who had prior revascularization, stress imaging studies are preferred because they provide better information regarding the coronary distribution and severity of myocardial ischemia when compared with EST.

24. Can I use the ECG tracings from the stress test to interpret my patient’s 12-lead ECG?

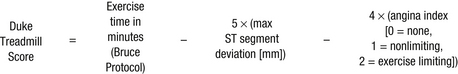

25. What is the Duke treadmill score?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Gibbons, R.J., Balady, G.J., Bricker, J.T., et al, ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing. Summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2002;106:1883–1892 Available at http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/106/14/1883.full Accessed March 26, 2013

2. Lauer, M., Froelicher, E.S., Williams, M., Kligfield, P., AHA Scientific Statement: Exercise Testing in Asymptomatic Adults 2005 Available at http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/112/5/771.full Accessed March 26, 2013

3. Hendel, R.C., Berman, D.S., Di Carli, M.F., et al. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 Appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(23):2201–2229.

4. Chou, R., Arora, B., Dana, T., Fu, R., Walker, M., Humphrey, L. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375–385.

5. Miller, T.D. Stress Testing: the case for the standard treadmill test. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:363–369.

6. Lee, T.H., Boucher, C.H. Noninvasive tests in patients with stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1840–1845.

7. Arena, R., Sietsema, K.E. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the clinical evaluation of patients with heart and lung disease. Circulation. 2011;123:668–680.

8. Chaitman, B.R. Exercise stress testing. In: Bonow R., Mann D.L., Zipes D., Libby P., eds. Braunwald’s heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. ed 9. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011:168–192.

9. Mayo Clinic Cardiovascular Working Group on Stress Testing. Cardiovascular stress testing: a description of the various types of stress tests and indications for their use. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1996;71:43–52.