chapter 8 Examining the Visual System

Normal Visual System in Infants and Children

In infants, the choroid gives a blue hue to the overlying thin sclera. In white persons, the iris is often poorly pigmented at birth, and the final eye color may not be established until at least 8 months of age. Examination by direct ophthalmoscopy shows the baby’s fundus to be pale, with the macula barely visible. As the child gets older, the fundus becomes darker, and the macula becomes darker than the surrounding retina. The macula then displays the easily recognized oval, bright reflection of the ophthalmoscope light, known as the macular umbo (Plate 8–1).

The birth process can be somewhat traumatic to the eyes. Many newborns sustain episcleral and retinal hemorrhages during vaginal delivery (see Fig. 4-14). These hemorrhages can be alarming to both parents and physicians but are harmless and usually disappear within 2 weeks. At birth, the nasolacrimal duct often is blocked at its junction with the nasal mucosa under the inferior turbinate. The blockage resolves spontaneously in more than 90% of cases, although it can remain until 1 year of age in some children, causing persistent tearing. A few affected children then need surgical treatment.

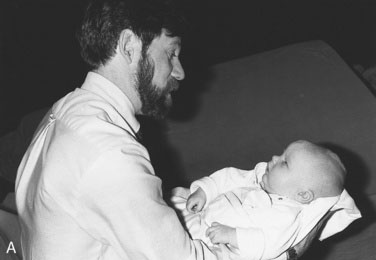

The process and rate of development of vision in infants are better understood than they were 10 years ago. Vision exists in several forms with different neuronal channels carrying specific visual functions, such as contrast sensitivity, orientation, movement, and hyperacuity. Each function develops at a different rate. For practical purposes, normal newborns can see a human face easily and demonstrate their visual ability by looking at it; they even follow the face with eye or head movement as it passes slowly before them at close range (Fig. 8-1). A baby’s ability to follow your face can be verified only when the baby is awake and alert, often just before or in the middle of a feeding session. This innate ability is paramount to the infant’s future development because few parents fail to form an emotional attachment to a little one who looks directly at them minutes after birth. By contrast, parents of a blind or strabismic infant who are unable to establish the interaction that comes with normal eye contact may have significantly greater difficulty developing the same level of emotional attachment to their offspring.

Definition of terms

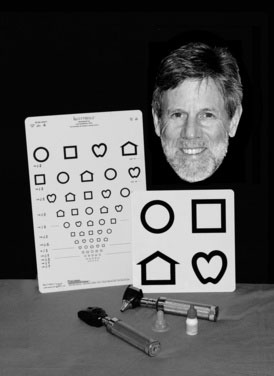

As an aid to diagnosis, this section contains a brief glossary of diagnostic terms that summarize the features to look for in children with eye problems. Box 8-1 and Figure 8-2 show the tools used to examine the eyes; Table 8-1 lists definitions and acronyms.

| Abbreviation/Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| Alt | Alternating strabismus; in almost all cases of strabismus, fixation (use of the eye to look at something) is with at least one eye at a time; if there is equal vision, the eyes will alternate fixation |

| APD | Afferent pupillary defect |

| CD | Corneal diameter |

| C/D ratio | Cup/disc ratio (cup size can be enlarged in persons with glaucoma) |

| CL | Contact lens |

| Comit | Comitant |

| E | Esophoria; the eye turns in only when there is interference with binocular vision (as with covering) |

| ET | Esotropia; one eye is turned in spontaneously |

| E(T) | Intermittent esotropia; the eye turns in only occasionally |

| IOL | Intra-ocular lens |

| IOP | Intra-ocular pressure |

| OD | Oculus dexter (Latin); right eye (English) |

| OS | Oculus sinister (Latin); left eye (English) |

| OU | Oculus uterque (Latin); each eye (English) |

| PERLA | Pupils equally reactive to light and accommodation |

| SLE | Slit-lamp examination |

| VA cc | Visual acuity with correction (with glasses or contact lens[es]) |

| VA sc | Visual acuity without correction |

| X | Exophoria |

| XT | Exotropia; one eye turns out (exodeviation) |

| X(T) | Intermittent exotropia; the eye turns out only occasionally |

* For example, a diagnosis of strabismus could be written as “Alt Comit X(T),” which would mean “alternating comitant intermittent exotropia.”

Cataracts

Cataracts are an important cause of leukocoria (white pupil, from the Greek; see Plate 8–2). Causes of pediatric cataracts include congenital rubella, metabolic disorders, and chromosomal anomalies. Cataracts can result from ocular inflammation (uveitis) or may accompany other ocular malformations. Many idiopathic cataracts are sporadic, but some are genetic. Some systemically administered medications cause cataracts. Steroids are common culprits, and they can cause glaucoma as well. Amblyopia in a child with a cataract is severe; therefore, cataracts in infants need immediate attention. Postoperative optical correction may require the use of contact lenses in infants, although intraocular lenses are becoming more popular in children older than 2 years.

Coloboma

A defect of closure of the embryonic fissure of the eye; hence, its inferonasal location in the eye. In mild form, only the iris is involved; in more severe cases, the choroid and the optic nerve can be involved (Plate 8–3). With optic nerve involvement, central nervous system (CNS) midline defects should be suspected, as in optic nerve hypoplasia (see definition of this term).

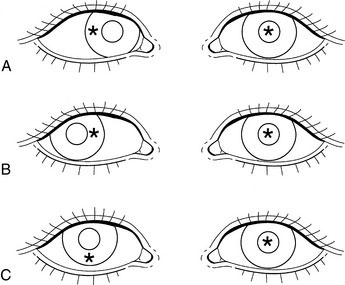

Head tilt

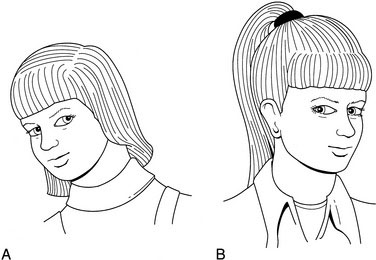

Abnormal head positions can be induced by a large array of conditions, many of them ocular. Typical is the compensatory head tilt seen in a fourth cranial (trochlear) nerve palsy, which is assumed to avoid diplopia and keep the eyes aligned. Without the tilt, the eyes show a vertical strabismus and the patient sees double (Fig. 8-3, A).

Head turn

An abnormal head position taken when reading or looking at a small visual target, typically caused by either a sixth cranial nerve (abducens) palsy or nystagmus. In the former, the head turn is used to avoid horizontal diplopia (Fig. 8-3, B); in the latter, the head turn improves vision by reducing nystagmic oscillations (null position).

Hemangioma (orbital, capillary)

Benign congenital tumors that grow rapidly when a child is between 1 and 6 months of age but tend to regress spontaneously later (Plate 8–4). Benign congenital tumors may cause severe amblyopia by pupillary obstruction, high astigmatism, or both. Early treatment is essential to preserve vision. Injection of steroids into the tumor, systemic treatment, glasses, and patching of the sound eye all may be necessary.

Hyphema

Bleeding into the eye’s anterior chamber (Plate 8–5). A trauma severe enough to cause a hyphema can involve other eye structures, leading to retinal detachment or injuring the trabecular meshwork of the iridocorneal angle and thereby causing glaucoma. Hyphema is the principal diagnosis in one third of eye traumas and is a major cause of ocular morbidity in children. Hyphemas rebleed in 6% of cases within 5 days of onset, causing further complications, but it may be possible to prevent rebleeding by decreasing physical activity and, in very selected cases, by administering systemic antifibrinolytic agents.

Leukocoria

A white pupil (Plate 8–2). This finding has major clinical implications. The differential diagnosis includes retinoblastoma and cataract. Delaying treatment of the former leads to death; delaying treatment of a cataract causes permanent loss of vision.

Lymphangioma

A diffuse benign tumor of the orbit that often bleeds internally and is another cause of ptosis, proptosis, or both. Almost impossible to resect completely in childhood, lymphangioma is a cause of astigmatism and amblyopia (Fig. 8-4).

Myelinated nerve fiber layer

Abnormal presence of myelin around the superficial nerve fibers of the retina near the optic disc (Plate 8–6). It can be so extensive that the pupillary red reflex can be made to appear white (leukocoria). The vision is generally normal except when the macula is heavily involved.

Optic nerve hypoplasia

A common cause of congenital blindness in children. Optic nerve hypoplasia often is misdiagnosed as optic atrophy because secondary nystagmus (sensory) makes the hypoplasia difficult to visualize. The optic nerve head (disc) is smaller than normal (Plate 8–7). Look for CNS midline defects, including the involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis with accompanying growth hormone deficiency (see Chapter 16).

Palsies (sixth, third, and fourth cranial nerves)

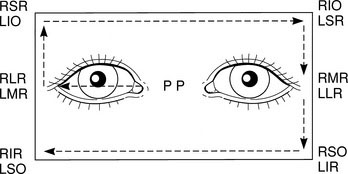

The extraocular muscles are innervated by various cranial nerves: the superior oblique by the fourth cranial nerve (also called the trochlear); the lateral rectus by the sixth cranial nerve; and all the others by the oculomotor nerve, the third cranial nerve, which also innervates the pupil and the ciliary body for accommodation. Any injury to these nerves induces a strabismus, the angle of which varies according to the direction of gaze—an incomitant strabismus. Typically, a head turn is seen in persons with sixth nerve palsy and lid ptosis in persons with third nerve palsy. Fourth cranial nerve palsy (trochlear) causes an ipsilateral hyperdeviation and a contralateral head tilt (see Fig. 8-3).

Periorbital cellulitis

Any inflammation around the orbit is cause for concern, and the differential diagnosis should include rhabdomyosarcoma (see later definition). When the orbital content is involved, ocular motility is decreased and the patient is at imminent risk of loss of vision. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis is an early complication in children younger than 5 years. Periorbital cellulitis (Plate 8–8) is most often associated with ethmoiditis in children who do not have a clear history of skin trauma or infection around the eye, and both computed tomography scanning and magnetic resonance imaging are invaluable for a clear evaluation of the best therapeutic regimen. This condition is far less common in areas of the world where Haemophilus influenzae B vaccine is used. Most cases of periorbital cellulitis require systemic antibiotic therapy.

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV)

The presence of a unilateral dense residual vascularized glial frond of tissue that originates from the optic nerve disc and projects toward the back of the lens. It is the first tissue present in the eye required to initiate the growth of the lens. In PHPV, the lens is abnormal and cataractous, causing a leukocoria; the differential diagnosis of leukocoria includes other forms of cataract and retinoblastoma. PHPV is associated with microphthalmos and cataracts. The vessels in the back of the lens can bleed, inducing a very rare but diagnostic hemorrhagic cataract. PHPV is a progressive malformation that requires early surgery to save the eye and possibly restore its vision (Fig. 8-5).

Plexiform neurofibroma

A type of hamartomatous formation found in persons with neurofibromatosis. In the orbit, it is accompanied by sphenoid bone defects with herniation of the contents of the anterior fossa into the orbital cavity. This condition may or may not cause visual problems, such as strabismus, astigmatism, and optic nerve dysfunction (Fig. 8-6).

Retinitis pigmentosa

A generic term describing a variety of retinal degenerations, including choroidal degenerations, diseases of either type of photoreceptors, and syndromes involving other organ systems (e.g., Laurence-Moon-Biedl and Alström syndromes in which progressive retinal degeneration is associated with obesity and other systemic dysfunctions) (Plate 8–9). Most patients with retinitis pigmentosa experience a severe visual deficit at an early age.

Retinoblastoma

The most important cause of unilateral or bilateral leukocoria, retinoblastoma occurs in 1 in 15,000 births and often is also present with a strabismus or a red eye (Plate 8–10). The gene for this condition is located on the long arm of chromosome 13. Retinoblastoma is most curable if diagnosed early. Later death from a second malignancy is a major concern in bilateral and autosomal dominant familial cases.

Uveitis

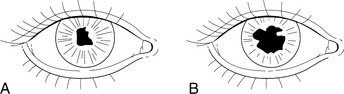

Inflammation of the uvea. In children, uveitis often occurs in persons with the monoarticular or pauciarticular forms of chronic rheumatoid arthritis(a term now more frequently used in pediatric practice than juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.) It occurs most often in girls 4 to 6 years of age who test seronegative for rheumatoid factor, seropositive for antinuclear antibody, and seronegative for human leukocyte antigen B27. The inflammation is usually chronic, indolent, and bilateral. Blindness may occur because of cataracts, glaucoma, or corneal disease. The eye stays white, without redness, until the end stage of the disease. The only possible clinical screening that can be performed between slit-lamp examinations involves a pupillary examination that can be taught to the parents (Fig. 8-7). The examination is difficult in dark-eyed persons but can be enhanced by dilating the pupils (during a lively conversation at the supper table or by pharmacologic means at the physician’s office).

Approach to the Physical Examination

General observation

Head Position

Ocular observations

Open Versus Closed Eyes

Red Eyes

Bigger-Than-Normal Eyes

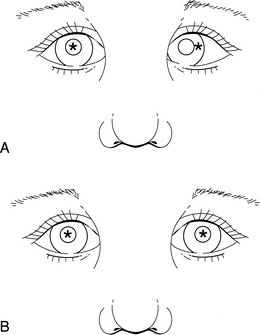

Eyes appear larger than normal in persons with congenital glaucoma (the cornea is bigger). A baby’s cornea should not appear to be bigger than that of an adult. To help make the comparison, have an adult hold the baby sitting forward on his or her lap, with both facing you. Have them put their faces close to each other so that the two pairs of eyes are in proximity. Comparison is easy with mothers and babies in a cheek-to-cheek position or with the baby’s head just below one parent’s chin (Fig. 8-9).

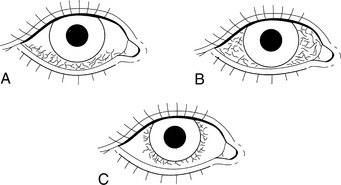

Demonstrating Corneal Light Reflexes

A normal shiny cornea shows a neat, crisp light reflection when a light source is aimed at it. You can see the reflection almost in the center of the child’s pupils when both eyes are looking at the same light source, held between you and the child at 25 cm. If the corneal light reflexes are not positioned symmetrically, assume that both eyes are not looking at the light (Fig. 8-10). Judging the position of the light reflexes requires practice; the reflex is neither highly specific nor terribly sensitive for detecting slight degrees of eye misalignment (strabismus), but it is a good start.

It also is useful to show parents what a pseudostrabismus really is: a common pediatric nondisease that often concerns parents and physicians unnecessarily. It is usually seen in younger children with broad, flat nasal bridges and epicanthic folds. When the child looks to one side or the other, the eye turned toward the nose becomes partly hidden under the epicanthic fold, creating a false impression of strabismus—an optical illusion (Fig. 8-11 and Plate 8–11). The eyes look turned-in because of the asymmetry of scleral show. You can show the true alignment with the corneal light reflexes. The corneal light reflexes can be evaluated quickly with the ophthalmoscope at the same time as the pupillary red reflexes (described later in this chapter), but an otoscope light is a better choice for a more careful evaluation of a deviation.

Demonstrating Pupillary Red Reflexes

Remember those Halloween party color photographs taken with a cheap flash camera, in which everyone looks at the camera flash and appears to have big red eyes? Look for the same effect when examining infants and children for the red reflex (Plate 8–12). Demonstration of the red reflexes requires the following conditions and instruments:

Set your direct ophthalmoscope at the widest beam setting. Turn the wheel until you see the patient’s eyes clearly, staying about 2 feet (60 cm) away from the child to prevent both unexpected uncooperative behaviors and accommodative pupillary constriction. Aim the beam so that it illuminates both pupils, and observe (Fig. 8-12). The first observation should confirm normal or abnormal corneal light reflexes. In newborns, this may be the only chance to combine observations of corneal and pupillary light reflexes, at least in the primary position (i.e., eyes looking straight ahead).

Abnormal red reflexes could be caused by problems such as an opacified cornea (as in Hurler syndrome, a mucopolysaccharidosis); cataract (opacity of the lens); or retinoblastoma, a potentially lethal retinal malignancy. Mild asymmetry of brightness between the reflexes is produced by large refractive errors and by various degrees of strabismus. Normal red reflexes are shown in Plate 8–11.

Specific Examination Techniques

Testing visual acuity

Face Follow Test

Testing for Optokinetic Nystagmus

Simple black and white stripes work well, but red and white stripes work even better (Fig. 8-13). You also can use an inexpensive striped necktie.

Testing for Fixation Behavior

Testing Visual Acuity Using LH

In the LH test, the child is given a plastic board with four symbols on it and is simply asked to point out on the board the symbol shown by the examiner on a typical visual acuity–type card hung on the wall. It is performed at a distance of 10 feet (3 m) for better compliance in younger children. The test, which is widely available, has components that are standardized for the 3-m distance and are made of durable plastic. The test also has decreasing spaces between letters proportional with the decreasing letter size; this feature maintains the crowding aspect of the test, which is important in testing for amblyopia. Every clinic or office should have this test kit to measure vision (Fig. 8-14).

Assessing extraocular movements and looking for incomitance

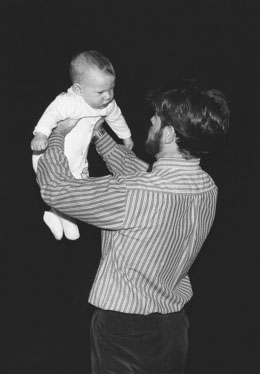

Spinning

The vestibular system has a major influence on eye movements. Spinning a child stimulates the vestibular system, which in turn stimulates the extraocular muscles. This method is used mainly for testing infants. To do it effectively and to appreciate what is actually going on with the child’s eyes, you must hold the child up in the air, facing you and tipped slightly forward, with his or her head a few inches away from yours (Fig. 8-15); watch the child’s eyes as you turn yourself and the child around, first in one direction (two or three turns), then in the other direction. The baby’s eyes should deviate in the direction of the turn. With this technique, not only will the youngster open his or her eyes, but the horizontal deviation of the child’s eyes will allow you to assess simultaneously the medial (third cranial nerve) and lateral (sixth cranial nerve) rectus muscles of both eyes. One word of caution: Do not spin the child for too long. After a few seconds, the surprise that prompts the child’s eyes to open can change to unhappiness at being suspended in the middle of nowhere and spinning dangerously in the arms of a stranger.

The Frame

Have an older child follow an object of interest (e.g., a red nipple placed on top of an otoscope that has been turned on) to the four corners of an imaginary frame around the face. This technique tests all of the extraocular muscles (Fig. 8-16). You can readily detect any anomaly of ocular movement, especially if you observe the corneal light reflexes carefully.

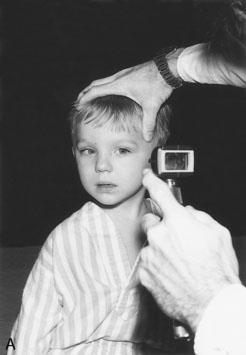

Twisting the Head

As a last resort, while the child looks at you, hold the top of his or her head and turn it quickly, first to one side and then the other (Fig. 8-17). This maneuver may upset the child a little, but it allows assessment, through the vestibular system, of the activity of the horizontal muscles. Perform this movement vertically to assess the vertical muscles (superior and inferior rectus muscles, innervated by the third cranial nerve).

Assessing visual fields

Assessing visual fields in children is not as daunting or difficult as it might seem. In most situations, you can tell the child to look for the wiggly fingers. Instead of asking a child to fix on a stationary target while you check the peripheral field, as is done with adults, ask the child to look for a more exciting target, as follows (Fig. 8-18):

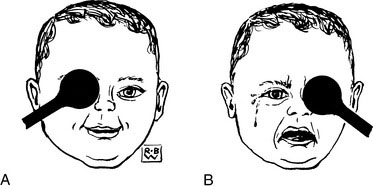

Cover test for strabismus and vision

The cover test also can tell you something about vision (Fig. 8-19). If you try to cover the child’s only good eye, you will be informed of that fact in more than one way: The child either cries or becomes uncooperative, or you cannot keep the eye covered because the child’s eye, his or her whole head, or a hand moves to reestablish the vision you have just interrupted. The child will get both you and your cover out of the way. Unfortunately, such a response may spell an end to the child’s cooperation.

Funduscopy in children

You should make the following three important observations as part of the funduscopy:

Lacrimal sac examination

The next step is to do the same in a normal newborn to realize the difference in size. Finally, try it in a patient with a presumed blocked tear duct (Fig. 8-20). You will discover that (1) it is difficult to feel the depression and (2) while you roll your finger, a significant amount of secretion will appear in the child’s eye.

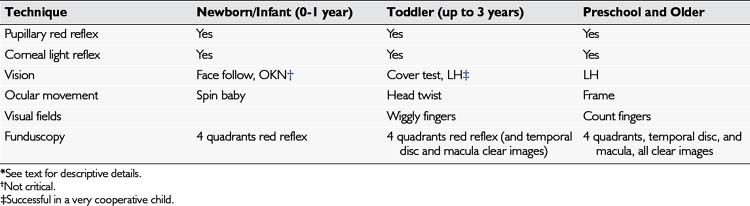

Applying Sequential Logic to Assess Children’s Eyes

The following five different clinical situations illustrate how to apply sequential logical assessment to common specific visual problems. Table 8-2 lists the main examination techniques to be used in each age group. It is worth mentioning that these techniques also form the basis for the recommendations made by most pediatric professional groups in North America for vision and eye screening examinations in children.

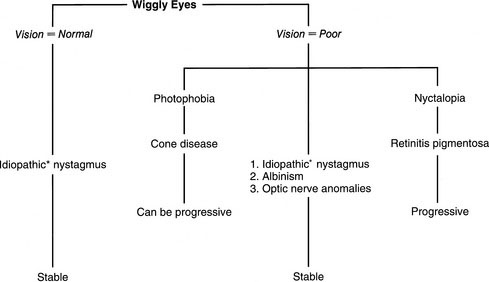

Case 1: Nystagmus

Nystagmus is frequently overlooked despite the fact that it is the most common presenting sign of debilitating, genetically determined ocular conditions. The presenting complaint is most often wiggly eyes (Fig. 8-22). See Table 8-3 for aspects to consider and questions to ask when a child has nystagmus. The first and most important question to answer is whether the child’s vision is good. If the vision is good, relax—the child most likely has idiopathic motor nystagmus, which is usually an early-onset hereditary condition (appearing at 3 months) with only moderate visual deficit.

| Aspects to Be Considered | Questions to Ask Parents |

|---|---|

| Evidence of poor vision | Toys held close to face? |

| Poor eye contact? | |

| Poor motor development? | |

| Photophobia | Squinting outdoors? |

| Opens eyes only in semidarkness? | |

| Stays up all night? | |

| Refuses to play outside? | |

| Nyctalopia | Cries when lights are out? |

| Runs into walls at night? | |

| Wets the bed? | |

| Family history | Nystagmus? |

| Progressive blindness? |

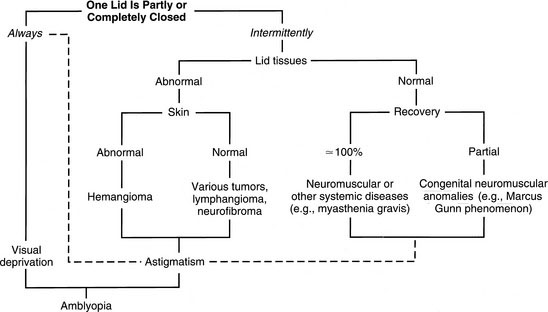

Case 2: Lid Ptosis

Lid ptosis (Fig. 8-23), which has important systemic and visual implications, is often poorly understood. Unilateral or asymmetric lid ptosis has greater clinical significance than bilateral ptosis. Systemic problems or other local lid abnormalities can be seen in persons with unilateral or intermittent ptosis. The child with ptosis often adopts a chin-up position, freeing the pupil to allow binocular vision.

The presenting complaint is most often droopy lid, for which Figure 8-24 presents a diagnostic algorithm. Also see Table 8-4 for aspects to consider and questions to ask for a child with ptosis. The most important question is whether the ptosis is constant. If the ptosis is constant, involving one or both eyes, vision is at risk, and early intervention is required to allow normal visual development in the obstructed eye. This situation is comparable with that of the child with congenital cataract, in which severe visual deprivation prevents establishment of the normal neuronal organization of vision.

| Aspects to Be Considered | Questions to Ask Parents |

|---|---|

| Hematoma | History of trauma? |

| Plexiform neurofibroma (see Fig. 8-6) | Birthmarks? |

| Plexiform neurofibroma in the family? | |

| Jaw-winking phenomenon (see Fig. 8-25) | Ptosis improves with drinking, sucking, and/or chewing? |

| Hemangioma (capillary) (see Plate 8–12) | Abnormal lid? |

| Bluer when crying? | |

| Lymphangioma (see Fig. 8-4) | Increase in size with colds? |

| Increase in size after trauma? | |

| Third cranial nerve palsy (ophthalmoplegia) | Little voluntary eye movement of one eye? |

| Acquired third cranial nerve palsy | Diplopia when lid open? |

| Third cranial nerve palsy and aberrant regeneration | Lid movements with attempted eye movements? |

| Myasthenia gravis | Ptosis gets worse intermittently in the afternoon? |

| Myasthenia, mitochondrial diseases | Poor gag reflex and/or poor feeding? |

| Progressive weakness during the day? |

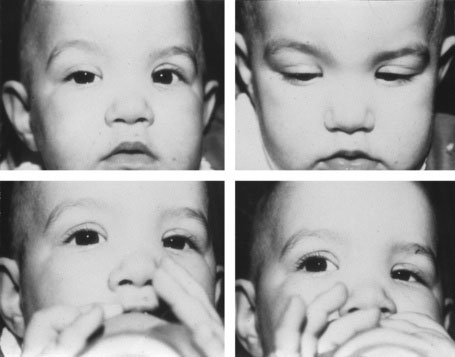

The lid’s appearance helps identify local tumors, such as hemangiomas, whereas a good neurologic examination, including assessment of ocular motility, often gives clues to rarer congenital misfirings, such as Marcus Gunn oculotrigeminal dyskinesia (jaw-winking phenomenon; Fig. 8-25), myasthenia gravis, and even mitochondrial diseases.

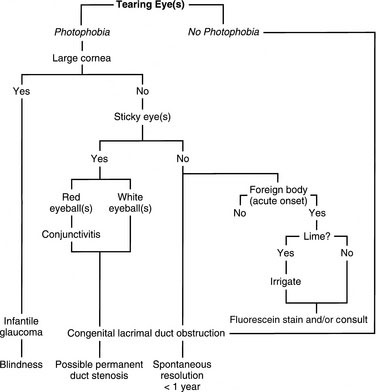

Case 3: Epiphora

Tearing, or epiphora, is the most common of ocular complaints, and the causes are innumerable, from a hysterical emotional reaction to a splash of a destructive alkali in the eyes. Figure 8-26 presents a diagnostic algorithm for a child presenting with tearing eyes. In young children, the differential diagnosis often is somewhere between a chronic conjunctivitis and the dreaded (albeit extremely rare) blinding infantile glaucoma or a potentially devastating herpes simplex keratitis.

See Table 8-5 for aspects to consider and questions to ask for a child with epiphora. The most important question to ask is whether photophobia is present. Equally important is assessment of corneal size, which is accomplished by comparing the child’s cornea with those of the parent on whose lap the child is sitting (facing you). An adult cornea has a horizontal diameter of 12 mm; anything bigger in a child is abnormal. Therefore, if an infant presents with teary eyes, photophobia, and enlarged cornea, the diagnosis is almost certainly infantile glaucoma, a potentially blinding but treatable disease. The disease can be unilateral in the early stages (i.e., only one cornea is enlarged).

| Aspects to Be Considered | Questions to Ask Parents |

|---|---|

| Blocked tear ducts | Two eyes first, then one only? |

| Worse with colds? | |

| Congenital glaucoma | Photophobia? |

| Constant tearing? | |

| Big eyes? |

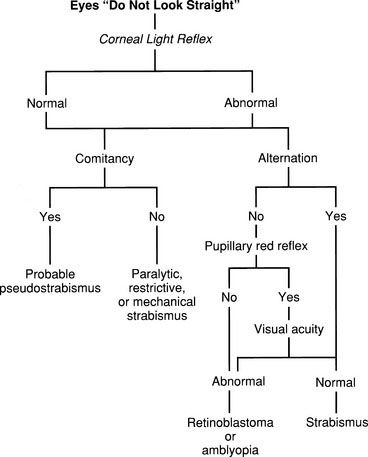

Parents commonly complain that the child’s eyes “do not look straight.” Figure 8-27 presents a diagnostic algorithm for this situation. Also, see Table 8-6 for aspects to consider and questions to ask for a child with strabismus. Immediately decide whether the corneal light reflections are normal. If they are normal in the primary position (looking straight ahead), check whether they are normal in other positions of gaze. An incomitant strabismus, which may show only in certain positions of the eyes and may or may not be present in the primary position, must be identified promptly. The cause of strabismus may be paralytic, restrictive, myogenic, or mechanical.

| Aspects to Be Considered | Questions to Ask |

|---|---|

| Intermittent esotropia | Worse when looking up close? |

| Intermittent exotropia | Worse when looking outside? |

| Large exophoria or esophoria | Worse when tired? |

| Migrainous ophthalmoplegia (third or fourth cranial nerve palsy) | Onset after a bad headache? |

| Idiopathic sixth cranial nerve palsy | Onset after a cold? |

| Rare congenital sixth cranial nerve palsy | Onset at birth? |

| “Congenital esotropia” (early-onset infantile) | Onset at about 3 months of age? |

| Accommodative esotropia | Onset at about 3 years of age? |

| Intracranial process with sixth and fourth cranial nerve involvement | Accompanied with or preceded by a chronic headache? |

| Onset of deviation (according to parents) | Ask the child to show you what he or she sees (diplopia signifies neurologic cause) |

| Inspect the family photo album for corneal light reflexes and abnormal head posture |

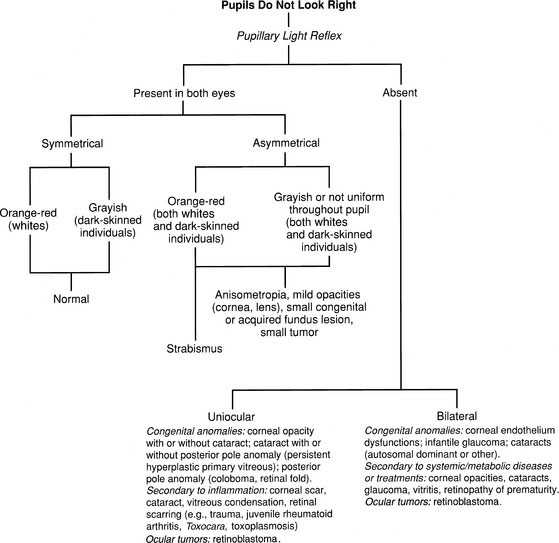

Case 5: Leukocoria

Although strabismus is a common condition with potentially major systemic implications and with obvious direct effects on visual function, leukocoria is an uncommon but ominous sign. The presenting complaint is most often an eye(s) or pupil(s) that does not look right, for which Figure 8-28 presents a diagnostic algorithm.

Absence of a pupillary light reflex is significant and can be caused by corneal or choroidal lesions or anything in between. A white or gray-white reflex, termed leukocoria, is caused by lesions dense and close enough to the crystalline lens to reflect most of the penetrating light. Cataracts and retinoblastoma are two classic examples. See Table 8-7 for aspects to consider and questions to ask for a child with leukocoria.

| Aspects to Be Considered | Questions to Ask |

|---|---|

| Localized lesion of the posterior pole, retinoblastoma | Seen only at certain angle? |

| Retinoblastoma | Onset about 1½years old? |

| Family history? | |

| Photos of the child with abnormal red reflex ? | |

| Toxocara canis (visceral larva migrans), retinal toxoplasmosis | Family pet (puppy or kitten) |

| Youngster likely to put dirt in his or her mouth (2-4 years)? | |

| Big retinal or disk coloboma | Onset at birth or very soon after? |

| Sarcoid or Candida vitritis | Sick child? |

| Uveitis with cataract and glaucoma | Arthritis? |

| Cataract and/or retinal detachment | History of recent eye trauma? |

| Cataract alone | Photos of the child with abnormal red reflex? |

| Maternal rubella? | |

| Child taking steroids? | |

| Trauma? | |

| Diabetes? | |

| Storage disease? | |

| Chromosome anomalies? | |

| Family history? | |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | Prematurity with low birth weight and use of oxygen? |

Canadian Paediatric Society Community Paediatrics Committee. Vision screening in infants, children and youth. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14(4):246-248.

Taylor D., Hoyt C. Practical paediatric ophthalmology. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1997.

Von Noorden G.K., Maumenee A.E. 4th ed. Atlas of strabismus. St Louis: Mosby, 1983.