Examining the skin

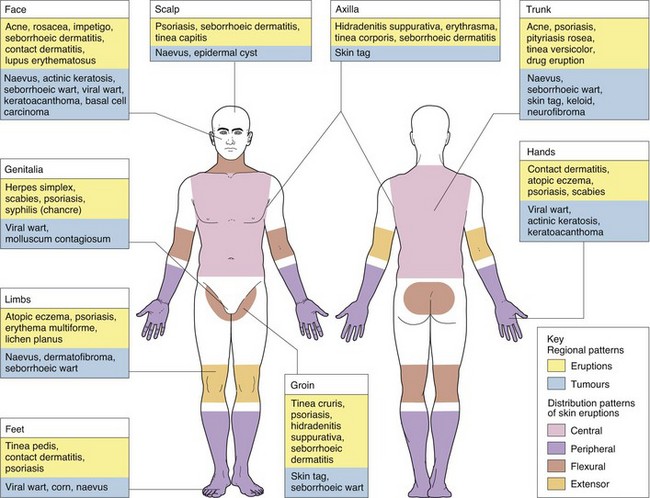

The skin needs to be examined in good, preferably natural, light. The whole of the skin should be examined, ideally; this is essential for atypical or widespread eruptions (Fig. 1). Looking at the whole skin often reveals diagnostic lesions that the patient is unaware of or may think unimportant. In the elderly, thorough skin examination often allows the early detection of unexpected but treatable skin cancers.

note the distribution and colour of the lesions

note the distribution and colour of the lesions

examine the morphology of individual lesions, their size, shape, border changes and spatial relationship; touch the skin – palpation reveals the consistency of a lesion

examine the morphology of individual lesions, their size, shape, border changes and spatial relationship; touch the skin – palpation reveals the consistency of a lesion

assess the nails, hair and mucous membranes, sometimes in combination with a general examination (e.g. for lymphadenopathy)

assess the nails, hair and mucous membranes, sometimes in combination with a general examination (e.g. for lymphadenopathy)

wear gloves when examining the mouth, genitals and perineum or if lesions may be infected

wear gloves when examining the mouth, genitals and perineum or if lesions may be infected

use special techniques, e.g. dermoscopy, microscopy of scrapings to look for fungal elements, or the use of Wood’s (ultraviolet A) light, where applicable.

use special techniques, e.g. dermoscopy, microscopy of scrapings to look for fungal elements, or the use of Wood’s (ultraviolet A) light, where applicable.

Distribution of eruption or lesions

Stand back from the patient and observe the pattern of the eruption (Fig. 1). Determine whether it is localized (e.g. a tumour) or widespread (e.g. a rash). If the latter, determine whether the eruption is symmetrical and, if so, peripheral or central. Note whether it involves the flexures (e.g. atopic eczema) or the extensor aspects (e.g. psoriasis). Is it limited to sun-exposed areas? Is it linear?

Dermatomal patterns are also seen. Herpes zoster (shingles) is the commonest example of this, but some naevi also appear in this guise or follow Blaschko’s lines (p. 13). Regional patterns (see Fig. 1), e.g. involvement of the groin or axilla, will suggest certain diagnoses to the experienced physician. For example, guttate psoriasis and tinea versicolor tend to occur on the trunk, whereas lichen planus often occurs around the wrists, and contact dermatitis frequently affects the face, feet or hands. The factors resulting in these patterns are complex but include skin anatomy, e.g. blood vessels, nerves, appendages or embryonic lines, and environment, e.g. moist conditions in the axillae, chemical contacts and sun exposure.

Morphology of individual lesions

A hand lens or dermoscope is often helpful in looking at individual lesions. Palpation (often neglected by medical students) is also important to determine the consistency, depth and texture. Definitions of lesions are given on page 14.

Lesions may be monomorphic (e.g. guttate psoriasis) or pleomorphic (e.g. chickenpox). There may also be secondary changes on top of primary lesions. The local configuration of lesions is often of diagnostic help (Table 1). Determine whether the lesions are grouped, linear or annular, or if they show the Koebner phenomenon (p. 28), whereby lesions appear in an area of trauma which is often linear, e.g. a scratch.

| Configuration | Disease |

|---|---|

| Linear | Psoriasis, lichen striatus, linear epidermal naevus, lichen planus, morphoea |

| Grouped | Dermatitis herpetiformis, insect bites, herpes simplex, molluscum contagiosum |

| Annular | Tinea corporis (ringworm), mycosis fungoides, urticaria, granuloma annulare, annular erythemas |

| Koebner phenomenon | Lichen planus, psoriasis, viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, sarcoidosis, vitiligo |

Nails, hair and mucous membranes

The nails, scalp and hair frequently show diagnostic and even pathognomonic signs (p. 68). With any unusual or atypical eruption, the mucous membranes of the mouth and genitalia may show important changes, such as oral involvement by Wickham’s striae in lichen planus, oral lesions in Kaposi’s sarcoma or vulval involvement with lichen sclerosus.

General examination

Case history 2

Six weeks ago, a 25-year-old man developed a slightly itchy linear area running down the medial aspect of his left leg (Fig. 3). Dermatological conditions giving a linear eruption include lichen planus, morphoea, psoriasis and linear epidermal naevus.

Diagnosis: lichen striatus, a self-limiting inflammatory dermatitis of unknown origin.

Special techniques and assessment of disease morbidity

The diagnoses of many skin conditions can be helped by special techniques, detailed on page 20. Photography is often used to record the state of a patient’s skin disease and allows comparisons at follow-up visits.

In the current management of skin diseases, it is sometimes necessary to make a quantitative evaluation of the disease and its impact on a patient’s life. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) states that a patient’s psoriasis must be of a certain severity, according to the psoriasis area and severity index, before treatment with a biologic agent is recommended (p. 115).

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The PASI is a numerical score of the extent and activity of a patient’s psoriasis. It is calculated by a reproducible formula based on the surface area and cutaneous features of the disease.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The PASI is a numerical score of the extent and activity of a patient’s psoriasis. It is calculated by a reproducible formula based on the surface area and cutaneous features of the disease.

Severity Scoring for Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD). The SCORAD gives a numerical value to the severity of a patient’s atopic eczema.

Severity Scoring for Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD). The SCORAD gives a numerical value to the severity of a patient’s atopic eczema.

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The DLQI is a measure of the impact of a skin disease on a patient’s social, work and personal activities over the preceding week.

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The DLQI is a measure of the impact of a skin disease on a patient’s social, work and personal activities over the preceding week.

Examining the skin

Examine the entire skin surface.

Examine the entire skin surface.

Use a hand lens and adequate illumination. Consider dermoscopy (p. 20).

Use a hand lens and adequate illumination. Consider dermoscopy (p. 20).

Gently palpate lesions to assess texture.

Gently palpate lesions to assess texture.

Look at the nails, hair and mucous membranes (oral and genital).

Look at the nails, hair and mucous membranes (oral and genital).

Observe for distribution, individual lesion morphology and configuration.

Observe for distribution, individual lesion morphology and configuration.

Always microscope scrapings if a fungal infection is a possibility.

Always microscope scrapings if a fungal infection is a possibility.