Examining the patient

Look at the patient!

It is easy to examine a patient carefully without properly observing them. A deliberate inspection of the patient’s face while taking the history may reveal vital clues even before the formal examination is commenced. Common examples include the pallor of iron deficiency anaemia, the lemon tint of megaloblastic anaemia, the jaundice of a haemolytic anaemia, and the plethora of polycythaemia. Before laying a hand on the patient, a careful inspection of the mouth and skin may also point to particular blood abnormalities or disorders (Table 8.1). The patient’s ethnic origin can be of relevance. Sickle cell anaemia is an unlikely diagnosis in a patient with white skin while pernicious anaemia is equally unlikely in a patient with black skin. Children with chronic blood disorders such as haemoglobinopathies are frequently thinner and shorter than their healthy peers.

Table 8.1

Observation of the patient with a blood disorder. Some common signs and their possible clinical relevance

| Clinical sign | Possible haematological abnormality |

| Face | |

| Pallor | Any anaemia |

| Lemon tint | Megaloblastic anaemia |

| Jaundice | Haemolytic anaemia |

| Plethora | Polycythaemia |

| Mouth | |

| Ulcers | Neutropenia |

| Glossitis | Megaloblastic anaemia |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | |

| Angular stomatitis | Iron deficiency anaemia |

| Candida (‘thrush’) | Immunosuppression |

| Skin | |

| Pallor | Any anaemia |

| Jaundice | Haemolytic anaemia |

| Excessive bruising | Coagulation disorder, thrombocytopenia |

| Purpuric/petechial rash | Thrombocytopenia |

| Leg ulcers | Sickle cell anaemia |

Examination of the lymph nodes

Lymph nodes may be enlarged in primary blood disorders and systemic diseases. Enlargement is referred to as ‘lymphadenopathy’ or just ‘adenopathy’. The differential diagnosis differs in generalised and localised forms of lymphadenopathy (Table 8.2). In practice, palpable lymphadenopathy is usually limited to the cervical, axillary and inguinal areas.

Table 8.2

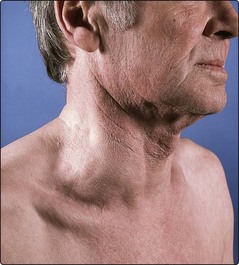

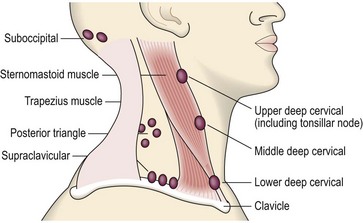

Enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes is the most common cause of a swelling in the neck and, if massive, may be easily visible (Fig 8.1). Following careful inspection of the neck, it is easiest to examine the cervical nodes from behind the seated patient, methodically palpating the anatomical areas detailed in Figure 8.2. As for all lumps, it is important to document not only the size and location of enlarged nodes, but also the shape, consistency and presence of tenderness. Lymphadenopathy secondary to infection is more often tender than that due to malignancy. Nodes involved by carcinoma are characteristically stony hard while those involved by lymphoma are more ‘rubbery’. The presence of cervical adenopathy should always prompt a thorough examination of the head and neck to detect a local cause (e.g. malignancy or infection); formal ear, nose and throat examination is often indicated.

Examination of the spleen

The spleen is enlarged in many blood disorders and in some systemic diseases (Table 8.3). The presence of a palpable spleen and its characteristics often narrows the differential diagnosis considerably. Examination of the spleen is frequently done badly. It is easy to miss a slightly enlarged spleen which is just palpable (‘tippable’) and it is also embarrassingly easy to miss a spleen which is massively enlarged. However, neither of these mistakes is likely if the examination is conducted as below.

Table 8.3

| Degree of enlargement | Centimetres palpable below costal margin | Causes |

| Slight | 0–4 | Various acute and chronic infections (e.g. septicaemia, tuberculosis) |

| Moderate | 4–8 | Haemolytic anaemia |

| Infectious mononucleosis | ||

| Portal hypertension | ||

| Massive | Greater than 8 | Myelofibrosis |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia | ||

| Polycythaemia vera | ||

| Lymphoma | ||

| Malaria | ||

| Leishmaniasis |

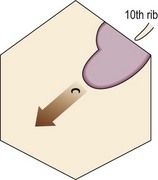

The patient should be examined on a suitable examination couch or bed and should be encouraged to relax. The whole abdomen is exposed. The examiner sits or kneels to allow palpation with a (warm) hand with the forearm horizontal to the abdomen. First, the abdomen is inspected for a visible mass and the patient is asked if they have any abdominal tenderness. It is normal to palpate the whole abdomen and then examine the major organs in turn. The spleen enlarges from below the tenth rib along a line heading for the umbilicus (Fig 8.3). Palpation for the spleen is commenced in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, otherwise massive enlargement can be missed. The hand is moved in stages towards the tip of the left tenth rib while the patient takes deep breaths. The edge of an enlarged spleen connects with the tips of the index and middle fingers during deep inspiration. If the spleen is not palpable using this technique, it is worth rolling the patient slightly onto the right side with the examiner’s left hand held firmly behind the left lower ribs (Fig 8.4). This latter manoeuvre may lift forward a slightly enlarged spleen and make it palpable on deep inspiration.

Fig 8.3 Schematic view of splenic enlargement.

The notch is frequently not palpable. The arrow shows the normal direction of enlargement.

The following features are typical of an enlarged spleen:

In practice an enlarged spleen is most likely to be misidentified as an enlarged left kidney. However, the kidney is not dull to percussion (it is covered by the colon) and it can be felt bimanually and balloted. It is worth listening with a stethoscope over an enlarged spleen as inflammation of the capsule may cause an audible ‘splenic rub’. The spleen is usually uniformly enlarged and it is not generally possible to identify the underlying disorder by palpation alone. The degree of enlargement does, however, give a diagnostic clue (see Table 8.3).