chapter 7 Examining the Head and Neck

General Observations

Initial observations of facial features are important: Does the head look proportional to the face? Is the shape abnormal? Are the left and right sides of the face symmetrical? Are the eyes too close together or too far apart? Are the ears normally placed? Is the chin appropriately developed? Does the child look like the parents? The ability to describe visual observations is an essential clinical skill that takes practice to master. The range of “normal” in pediatric physical examination is extremely broad. Never, ever use offensive, demeaning terms such as “funny looking kid” to describe dysmorphic children. Describe the noted differences or asymmetries precisely. The child may look like a parent because they both have an autosomal dominant dysmorphic syndrome (see Chapter 5).

Approach to the Physical Examination of the Head

Examining the head

Head Shape

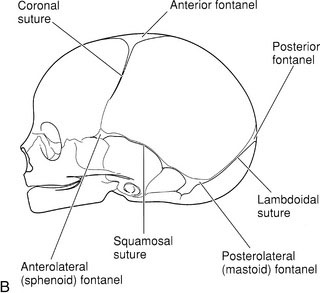

Craniosynostosis of the sagittal suture limits the skull’s width. As a result, compensatory excess growth occurs along the anteroposterior axis and possibly in the height of the skull, which produces a scaphocephalic shape, that is, a long, narrow skull (Fig. 7-1). Premature closure of the coronal suture results in a tall, wide head. When a suture closes prematurely, a palpable firm bony ridge sometimes is present along the suture line. Do not confuse this finding with normally overlapped sutures that are felt soon after birth.

Head Measurement

Accurate measurement of head circumference is surprisingly difficult. Measure the largest circumference possible by wrapping the tape around the most prominent parts of the forehead and occiput (Fig. 7-2). You should routinely take three measurements. If these measurements differ, you need to refine your technique. Even a slight variation in the position of the measuring tape changes the result significantly. Many infants and young children actively dislike head circumference measurement. Because a calm, cooperative child may become fretful, fearful, and oppositional when you attempt to obtain this measurement, it is best to leave it until the end of the examination. A parent’s assistance may be essential. I have found that the task is easier to accomplish when the infant is fed or cuddled and when the young child distracted with a toy or play activity.

The head circumference measurement must be plotted on a standardized head circumference graph. As with all standardized charts and graphs, no single value represents a “normal” head circumference (see Chapter 3). Measurements of new immigrants from various ethnic and racial groups may plot in the lower percentiles. Remember that, by definition, 3% of the normal population will have head circumferences that are below the third percentile or above the ninety-seventh percentile.

Fontanels

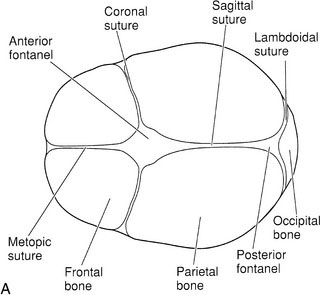

The fontanels are the gaps between bones in the infant skull where three skull bones meet (Fig. 7-2, A and B). Gentle palpation of the fontanels is a routine part of the newborn examination.

Increases in intracranial pressure, such as in meningitis, are reflected by changes in palpable tension of the fontanel and loss of normal venous pulsations (Fig. 7-3). A normal fontanel may feel full when the infant lays flat, cries, or struggles. It is best to assess anterior fontanel tension only when the infant is calm and held upright. With dehydration, the fontanel will appear sunken. Practice and palpation of dozens of fontanels will educate your fingers to detect abnormalities in size and tension. Each infant is his or her own standard. Serial assessments with careful descriptions of findings facilitate early detection of raised intracranial pressure.

Examining the ears

Hearing

Always ask parents if they have any concerns about their child’s ability to hear. Parents often suspect a hearing problem months before their child’s health care providers do. Audiologists are now able to measure hearing in infants from birth. The assessment of children with anomalies of the head and neck must always include formal hearing testing because the incidence of hearing problems is higher in children with such anomalies. Likewise, parental concerns about lags in language development should result in prompt audiologic evaluation. Delayed expressive language milestones may indicate hearing dysfunction (see Chapter 6).

Shape and Position

Start with a close inspection of the external ears. Are both present and normally formed, or do they fit the criteria for low-set ears? (See Chapter 5.) Do not be fooled by posteriorly rotated ears. If the vertical axis of the pinna is tilted posteriorly, the ear may appear to be low set. Minor anomalies of the ears such as skin tags, pits, or fistulas just anterior to the tragus are common and usually are of no major significance. Inspect and palpate the mastoid and postauricular areas. Gently move the pinna and tragus; any tenderness suggests otitis externa.

Positioning the Child

The otoscope should be held in either the “forehand” or “backhand” position—that is, with the thumb pointing either toward the light or toward the handle (Fig. 7-4, A–D). The advantage of the latter position is that it allows the back of your hand to lay against the face and, with any sudden movement, your hand moves with the child’s face. In other words, the position of the speculum relative to the ear does not change when the baby moves, and you avoid causing pain. Many examiners use the forehand position with equal comfort, especially if they use their opposite hand to stabilize the baby’s head.

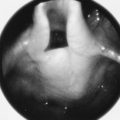

Tympanic Membrane

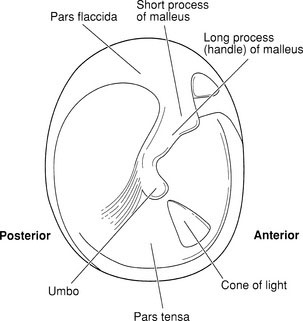

Study Figure 7-5 to acquaint yourself with the visual landmarks of the tympanic membrane. Textbook and atlas photographs do not do justice to the full range of normal appearance or the changes in color seen with wax, fever, or crying. It is essential to examine as many ears as possible to appreciate the range of normal.

Pneumatic Otoscopy

Pneumatic otoscopy, which is a relatively simple procedure, can yield important information about middle ear pressure. It works on a simple principle. Remember the example of the plastic wrap and the effect of changes in middle ear pressure? Now imagine that the pressure changes are imposed from the other side of the membrane (i.e., from the external auditory canal). To perform this procedure, use an otoscope with a pneumatic bulb attachment(it is best to carry your own) and a special speculum with an expanded tip that forms an airtight seal in the external canal without the application of pressure. As an alternative, a small piece of rubber tubing placed over the tip of a standard speculum provides an excellent seal. Look through the otoscope while squeezing and releasing the rubber bulb (Fig. 7-6).

Examining the mouth

Position for Examination

It is best to approach the examination positively. Show the child the flashlight or otoscope light without a tongue depressor in sight. Allowing some children to assist by placing a hand on the light or even on the tongue depressor gives them a sense of control. Infants are best examined supine with the arms restrained (Fig. 7-7). Beyond early infancy, it is best to examine infants and children in the sitting position (Fig. 7-8). Encourage the child to open his or her mouth widely and vocalize “aaahhh.” In many children, the soft palate rises and the tongue descends spontaneously when the mouth is fully opened, allowing a clear view, which may include the epiglottis. In other children, even with their full cooperation, it will be necessary to depress the base of the tongue with the tongue depressor to view the full oral cavity. Any pressure at the base of the tongue results in a brief gagging response, which causes the soft palate to rise and allows brief inspection of the posterior pharyngeal wall.

FIGURE 7-7 Examination of the mouth, supine position. The mother restrains the infant’s arms at the sides.

Examining the nose

Next, inspect inside the nose. You will need a nasal speculum and light or a regular otoscope with a large nasal speculum. Remember that the anterior septum, Little’s area, is extremely vascular and sensitive. Any trauma to this area will induce pain and possibly bleeding, as well as an uncooperative child and an upset family. Insert the speculum slowly, being careful to follow the floor of the cavity that runs toward the occiput. Gentle pressure against the lateral wall will expose the nasal turbinates and mucosa. Observe the presence of edema, pallor, inflammation, bleeding, or secretions. Swollen, pale turbinates that obstruct the nasal airways partly or completely are the hallmarks of nasal allergy. Polyps may be seen as pale boggy masses that occlude posteriorly. Note if the nares are patent and allow equal air passage through both. In newborns, it is essential to determine bilateral patency. Choanal atresia on both sides may lead to cyanotic episodes and apnea in infants who are all obligate nasal breathers (see Chapter 4).

Approach to the physical examination of the neck

Lymph Nodes

Review the anatomy of head and neck lymph nodes. The glands are widely distributed and easily accessible. Use both hands simultaneously, facing the child at his or her eye level. Move your hands along the occipital ridges, then to the posterior hairline and postauricular areas, before moving forward and downward along the posterior and anterior cervical chains (Fig. 7-9). The nodes just below the angle of the jaw are the ones most frequently inflamed and swollen, a condition usually associated with minor viral respiratory infections. Do not forget the submental area and supraclavicular fossae.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Preventive oral health intervention for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1387-1394.

Canadian Paediatric Society Safe sleep for babies. (Web site). http://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/pregnancy&babies/safesleepforbaby.htm.

Bluestone C. 4th ed. Paediatric otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003.

Krol D.M., Keels M.A. Oral conditions. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28(1):15-21.

Canadian Paediatric Society. Preventing flat heads in babies who sleep on their backs. (Web site). http://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/pregnancy& babies/Flatheads.htm.