CHAPTER 48 Examination of the Cervical Spine

SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS

For example, cervical spinal range of motion is perhaps the most commonly performed assessment, common to most if not all practitioners, in the assessment of the patient presenting with neck pain. Notwithstanding the popularity of this examination component, there is a wide range of intra-subject variability depending upon the time of day it is measured. In addition, within a given individual, motion in a particular plane differs according to where the starting point of the motion is measured. Accordingly, establishing normal ranges for spinal motion is challenging.1,2

This has led to the development of various devices and technologies that can measure spinal range of motion more precisely.3–7 While certain devices have shown improved reliability as compared to manual physical examination techniques, the use of such devices is not commonplace in clinical practice, leaving the practitioner to rely upon manual techniques to guide clinical decision-making.

Compounding these reliability issues is the notion that impaired spinal range of motion correlates with impaired spinal function. In spite of evidence demonstrating a lack of correlation between loss of range of spinal motion and spinal dysfunction,8,9 the use of range of motion as a diagnostic tool remains well engrained in medical culture. Accordingly, range of motion models are regularly used as the basis upon which spinal impairment is rated.

Even more problematic is the attempt to establish whether a particular spinal motion segment, within the multiarticulated spine, has an abnormally restricted or lax range of motion. Despite numerous descriptions of techniques for the palpation of spinal structures, the inter-rater reliability and validity for motion palpation are both lacking in literature support.10–13

The quest for sources of anatomic pain generators has led examiners to teach provocative maneuvers that are designed to provoke local or referred pain.14 As a result, many syndromic diagnoses have included reproduction of a patient’s habitual pain as an essential diagnostic element. Nevertheless, the combination of the subjectivity of the pain response to palpation and the inherent biases of both examiner and examinee, have limited the predictive value of this aspect of the examination.15,16

WHY EXAMINE THE SPINE AT ALL?

Finally, non-specific spinal pain implies pain of non-ominous and non-neurogenic origin. In general, this diagnostic category is consistent with a more benign prognosis than the other two categories. The anatomic origin, if detectable by alternate means, may be discrete or diffuse. The spinal examination is often non-specific and exhibits wide variability among patients in this descriptive category.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Since there is often an overlap in the symptoms associated with upper limb conditions and neck conditions referring to the upper limb, evaluation of the cervical spine should not only include a detailed neurological evaluation of the upper limbs, but also an examination of the upper limb joints that could potentially be the source of the presenting symptoms. Symptoms referable to the shoulder often mirror presenting complaints frequently seen in the cervical spine. The examination of the upper limb joints is outside the scope of the present chapter, so the focus will be on the remaining elements of the cervical spinal evaluation. For further information on the shoulder, please refer to Chapter 49.

Inspection

Poor posture, in particular, poor sitting posture, is considered to be a significant contributor in back and neck pain.17 When sitting in a slumped or unsupported position, there is a loss of lumbar lordosis, which results in a compensatory thoracic kyphosis. Consequently, there is a resultant compensatory forward inclination of the head with flexion of the lower cervical spine and hyperextension of the upper cervical pole to level the head horizontally.

Range of motion

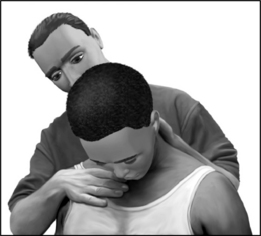

The patient should be given simple commands such as, ‘Touch your chin to your chest,’ ‘Look up to the sky,’ etc. By placing one hand on the head or chest, the examiner can also provide proprioceptive cues to guide the patient through his active motion (Fig. 48.1). In this way the unrehearsed patient is easily able to perform the requested active range of motion with confidence, and without the need for the examiner to demonstrate the required maneuver.

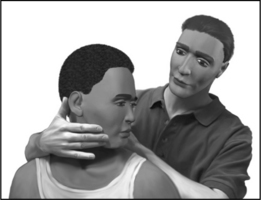

At the end of the patient’s active range, gentle over-pressure can be applied to determine the end-feel and the extent of the passive range (Fig. 48.2). This overpressure also allows the examiner to differentiate between the anatomical versus physiological end range. Palpation will be discussed below.

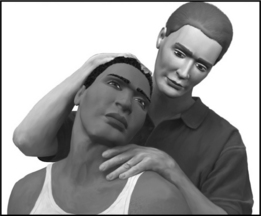

In general, passive ROM (PROM) is greater than the active (AROM), and PROM is increased in the supine versus sitting position. This positional ROM increase is due to the relaxation of resting muscular tone that normally holds the head against gravity. A primary example is the relative ease with which the patient is able to approximate his ear to his shoulder with side-bending when supine as compared to sitting (Fig. 48.3).

In the supine examination, cervical extension may be evaluated with the head and cervical spine off the end of the table. Cervical extension can then be performed with passive assistance with one of the examiner’s hands guiding motion and the other blocking motion at the lower, mid and upper cervical spine (Fig. 48.4). Evaluation of flexion is then assessed by resting the examinee’s head against the examiner’s crossed arms and trunk (Fig. 48.5).

With the aforementioned wide variability in cervical ROM, and the many associated factors that influence an examiner’s ability to validly measure range of motion, it is perhaps even more important to assess and document range of motion qualitatively. In this regard, it is essential to understand that the different regions of cervical spine serve different functions.

The examiner should be mindful that both age and possibly gender affect cervical ROM. Chen and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 13 reports looking at these correlations. The majority of these studies found that ROM generally decreases with age. Most found that women had greater range of motion than men, although the gender differences were not statistically significant.1

As discussed previously, spine ROM is a major determinant of impairment in many disability rating schedules. A study by Lowery et al. suggests that impairment ratings based solely on decreased ROM produces less than accurate results.8 In this study, 81 healthy subjects were evaluated using a double inclinometer method. They concluded the current method of impairment determination, based on spinal motion criteria, overestimates impairment by up to 38%. Accordingly, impairment guides have moved away from a range of motion model of assessment of spinal impairment to one based on diagnosis-related estimates.

Range of motion evaluation, however, should not be dismissed entirely in correlating pathology. Dall’Alba et al. demonstrated that ROM alone allowed blinded evaluators the ability to discriminate between asymptomatic persons and those with persistent whiplash-associated disorders in 90% of their subjects, with a sensitivity of 86.2% and specificity of 95.3%.18 Perhaps other methods for impairment evaluation should be developed and incorporated that are more specific for individuals with true functional impairment and that account for age-related differences in spinal motion.

Palpation

In general, bony or segmental palpation of the spine is best performed with the patient supine since the postural muscles are better relaxed in this position, providing better access to bony landmarks. In this position, longitudinal friction can be applied to the posterior articular pillars at almost each cervical segment. Pressure can be applied along the groove located between the paraspinal muscles and the trapezius. This can occasionally be facilitated by slightly rotating the examinee’s neck away from the side of palpation (Fig. 48.6).

There must be a familiarity with bony landmarks, including the external occipital protuberance, the spinous processes of each cervical vertebrae, and regions overlying the Z-joints. The occipital protuberance is found at the posterior skull in the midline. The spinous processes of C2, C6, and C7 are most obvious. The first prominence palpated caudal to the occiput is C2. The next most obvious spinous processes distally are C6 and C7.

Special neural tests

After completing an evaluation of motion in the cardinal planes, the examiner can evaluate the effect of complex motions by combining various degrees of sagittal, frontal, and transverse planar motion. In 1944, Spurling and Scoville, first described the ‘neck compression test’ stating that it is almost pathognomonic of a cervical intraspinal lesion.19 They performed the test by side-bending the neck towards the painful side and applying axial pressure on the top of the head to reproduce the patient’s characteristic pain and radicular symptoms. They did not indicate how long this position was to be held or with how much axial loading. Side-bending the neck away from the lesion usually provides relief.

Tong et al. performed a cross-sectional study to determine the sensitivity and specificity of Spurling’s maneuver for cervical radiculopathy.20 The test was performed as in Spurling’s original description, and was considered positive if it reproduced pain or paresthesias that began in the shoulder and radiated distally to the elbow. They concluded that Spurling’s maneuver is not very sensitive (30%) but is specific (93%) for cervical radiculopathy diagnosed by electromyography. Therefore, it appears not as useful as a screening test, but more clinically useful in confirming a cervical radiculopathy.

Bradley and colleagues suggested a three-stage protocol to the test.21 If symptoms are reproduced, subsequent stages need not be performed. The first stage consists of axial compression with the cervical spine in neutral position. The second stage involves compression with the neck in extension, and the third stage places the neck in extension and lateral rotation to the unaffected side first and then to the symptomatic side, both with axial compression. Radicular pain into the arm is considered a positive test and indicates irritability of a nerve root. The dermatomal distribution of the symptoms suggests involvement of a specific nerve root. The neck positions of each stage of the test progressively narrows the intervertebral foramen, which may be seen in conjunction with uncovertebral and zygapophyseal hypertrophy and disc herniations.

A similar test, called the maximal compression test, incorporates side-bending and rotation towards the symptomatic side, along with extension and axial compression (Fig. 48.7). This combination of positions causes maximal neuroforaminal compression and is positive if pain radiates into the arm. Most clinicians perform the maximal compression test but erroneously refer to it as the Spurling’s maneuver, when in fact it is a ‘modified’ Spurling’s compression test.

Another provocative maneuver used in patients with cervical radiculopathy is the application of lateral pressure against the vertebrae. This maneuver, also known as the doorbell sign, is considered positive when pressure to the anterolateral cervical spine reproduces referral of pain into the ipsilateral upper limb (Fig. 48.8). A positive sign is considered to be consistent with spinal nerve irritability or other unspecified spinal segmental dysfunction.

The distraction test is used to diagnoses spinal nerve irritation by alleviating radicular symptoms. The examiner places one hand on the patient’s chin and the other hand around the occiput and slowly applies upward traction to the patient’s head. The test is positive if the patient reports a decrease in radicular symptoms. The shoulder abduction relief sign, also called Bakody’s sign, is observed when the patient abducts the arm and places the hand or forearm on the top of the head. This arm placement, which may be performed subconsciously by the patient for symptomatic relief, is also indicative of presence of cervical nerve root traction that is being alleviated as a result of this maneuver.

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) should be tested as part of the comprehensive cervical examination. Classic, or neurogenic, TOS occurs when the lower trunk of the brachial plexus becomes compressed within the scalene triangle by a cervical rib, fibrous band of tissue, or from an elongated C7 transverse process. In TOS, neck pain is rarely a prominent symptom.22 The patient may complain of deep, aching pain in the ulnar side of the forearm, occasionally involving the hand. Subjective hand weakness and clumsiness may be present. Muscle wasting may be seen in the thenar eminence, particularly involving the abductor pollicis brevis. This is also referred to as the Gilliatt-Sumner hand.23 There is sometimes decreased sensation on the ulnar side of the hand. Roos describes several methods to reproduce symptoms of classic TOS.24 The more well known of the tests, also referred to as Roos’ test, involves a 3-minute elevated arm stress test. The shoulder is abducted to 90° and externally rotated, and the elbow is flexed at 90°. Additional stress is incorporated by asking the patient to open and close the hands for the duration of the test. The test is considered positive if typical upper limb symptoms are reproduced. Another less-known TOS test was also described by Roos. Percussion or light pressure held for 30 seconds over the supraclavicular fossa may reproduce pain, thereby distinguishing these symptoms from those emanating from the cervical spine.

Compression of the subclavian vessels has been termed vascular TOS. Adson’s maneuver evaluates for obliteration of the radial pulse when the arm is placed at the side in a slightly extended and externally rotated position with the head laterally rotated to the contralateral side. However, the false-positive rate is high.25 Furthermore, Wright’s test is positive when the radial pulse is diminished when the arm is placed in a horizontally abducted position with the head turned to either side. This indicates only positional compression of the subclavian artery, and is not necessarily indicative of vascular TOS. In Wright’s series of 150 asymptomatic normal subjects, 92.6% had reduction of the radial pulse in this position, calling into question the clinical utility of this test.26

Coppieters et al. tested the reliability of neural provocation tests in both the laboratory and clinical setting.27 Their study, focusing on median bias dural tension, demonstrated that pain provocation during neurodynamic testing is a stable phenomenon with good inter-tester and intra-tester reliability with intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.98.

The neurologic examination

Key reflexes to be evaluated include:

Key muscle groups to be evaluated include:

Key sensory areas to be evaluated correspond to regions of minimal dermatomal overlap including:

The triceps reflex is performed with patient’s forearm supported comfortably by the examiner. The reflex may be augmented by slightly increasing the elbow flexion, or by asking the patient to very gently push away to activate the triceps.

Simple commands should be given to the patient in order to evoke the desired patient response. Generally, the examiner should position the limb in the position to be tested (Fig. 48.9). The patient should be told, ‘Don’t let me move it.’ Prior to resisting, the examiner can apply a few brief jerks in the direction of the resistance in order to give proprioceptive cues to guide the patient through their resisted motion.

NECK OR SHOULDER DYSFUNCTION?

1 Chen J, Solinger AB, Poncet JF, et al. Meta-analysis of normative cervical motion. Spine. 1999;24(15):1571-1578.

2 Chiu TT, Sing KL. Evaluation of cervical range of motion and isometric neck muscle strength: reliability and validity [see comment]. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(8):851-858.

3 Dvir Z, Prushansky T. Reproducibility and instrument validity of a new ultrasonography-based system for measuring cervical spine kinematics. Clin Biomech. 2000;15(9):658-664.

4 Lantz CA, Chen J, Buch D. Clinical validity and stability of active and passive cervical range of motion with regard to total and unilateral uniplanar motion. Spine. 1999;24(11):1082-1089.

5 Schaufele MK, Boden SD. Physical function measurements in neck pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14(3):569-588.

6 Tousignant M, de Bellefeuille L, O’Donoughue S, et al. Criterion validity of the cervical range of motion (CROM) goniometer for cervical flexion and extension. Spine. 2000;25(3):324-330.

7 Tousignant M, Duclos E, Lafleche S, et al. Validity study for the cervical range of motion device used for lateral flexion in patients with neck pain. Spine. 2002;27(8):812-817.

8 Lowery WDJr, Horn TJ, Boden SD, et al. Impairment evaluation based on spinal range of motion in normal subjects. J Spinal Dis. 1992;5(4):398-402.

9 Parks KA, Crichton KS, Goldford RJ, et al. A comparison of lumbar range of motion and functional ability scores in patients with low back pain: assessment for range of motion validity. Spine. 2003;28(4):380-384.

10 Najm WI, Seffinger MA, Mishra SI, et al. Content validity of manual spinal palpatory exams – a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2003;3(1):7.

11 Pool JJ, Hoving JL, de Vet HC, et al. The interexaminer reproducibility of physical examination of the cervical spine. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2004;27(2):84-90.

12 Strender LE, Lundin M, Nell K. Interexaminer reliability in physical examination of the neck. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1997;20(8):516-520.

13 van Mameren H, Sanches H, Beursgens J, et al. Cervical spine motion in the sagittal plane. II. Position of segmental averaged instantaneous centers of rotation – a cineradiographic study. Spine. 1992;17(5):467-474.

14 Dvorak J. Epidemiology, physical examination, and neurodiagnostics. Spine. 1998;23(24):2663-2673.

15 Ohrbach R, Gale EN. Pressure pain thresholds, clinical assessment, and differential diagnosis: reliability and validity in patients with myogenic pain. Pain. 1989;39(2):157-169.

16 Sandmark H, Nisell R. Validity of five common manual neck pain provoking tests. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1995;27(3):131-136.

17 Black KM, McClure P, Polansky M. The influence of different sitting positions on cervical and lumbar posture. Spine. 1996;21(1):65-70.

18 Dall’Alba PT, Sterling MM, Treleaven JM, et al. Cervical range of motion discriminates between asymptomatic persons and those with whiplash [see comment]. Spine. 2001;26(19):2090-2094.

19 Spurling RG, Scoville WB. Lateral rupture of the cervical intervertebral disc. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1944;78:350-358.

20 Tong HC, Haig AJ, Yamakawa K. The Spurling test and cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 2002;27(2):156-159.

21 Bradley JP, Tibone JE, Watkins RG. History, physical examination, and diagnostic tests for neck and upper extremity problems. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1994.

22 McGillicuddy JE. Cervical radiculopathy, entrapment neuropathy, and thoracic outlet syndrome: how to differentiate? Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1(2):179-187.

23 Huang JH, Zager EL. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(4):897-902.

24 Roos DB. Congenital anomalies associated with thoracic outlet syndrome. Anatomy, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Surg. 1976;132(6):771-778.

25 Adson W, Coffey RJJr. Cervical rib: a method of anterior approach for relief of symptoms by division of the scalenus anticus. Ann Surg. 1927;85:839-857.

26 Wright IS. The neurovascular syndrome produced by hyperabduction of the arms. Am Heart J. 1945;157:1-19.

27 Coppieters M, Stappaerts K, Janssens K, et al. Reliability of detecting ‘onset of pain’ and ‘submaximal pain’ during neural provocation testing of the upper quadrant [erratum appears in Physiother Res Int 2002; 7(4):following 250]. Physiother Res Int. 2002;7(3):146-156.