CHAPTER 1 Evolving practice and shifting boundaries in gastrointestinal tract imaging

Advances in GI imaging

CT has been the mainstay of staging for most GI cancers, although we are seeing an increasing role for ultrasound and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, particularly in peri-rectal imaging. PET (positron emission tomography) and hybrid scanning methods are also likely to have an expanding role in the assessment of more complex cases, particularly in the investigation of cancer recurrence or identification of an unknown primary cancer.

Shifting professional boundaries

The gradual refinement of fluoroscopic techniques, coupled with the progressive exploration of new imaging modalities, has resulted in a much wider contribution of radiology to the gastrointestinal (GI) patient care pathway. Over the last three decades, there has been a huge shift in the role of the professions that are involved in providing the GI radiology service, particularly in the UK (Nightingale and Hogg, 2003a, 2007). However, the UK is not alone in this, with gradually shifting professional boundaries being seen within other English-speaking countries, including the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

The health services of the world are highly complex organizations, often being among the largest national employers. Introducing radical change into such organizations is challenging, as they often have many stakeholders with different needs to satisfy. Analysis of a number of historical role developments, both within and outside radiology, suggests that a range of overlapping drivers is necessary to implement the changes effectively (Box 1.1) (Nightingale and Hogg, 2003b). In the early 1990s, a major shift in professional roles began to take place within UK radiology departments. One of the most rapid to be adopted was the introduction of radiographer-performed double contrast barium enema (DCBE) examinations (known as the air contrast barium enema examination in the USA). The introduction of this role will be explored further, considering the relevant drivers that came together to result in successful implementation on a national scale.

A perceived deficiency in the service

According to the UK professional body, The College of Radiographers (2006), diagnostic imaging and interventional services have increased by 2.5–5% per annum over the last 10 to 12 years. This continuing rise in demand for imaging services, coupled with a shortage of radiologists, led to UK radiology services being severely over-stretched. The shortfall in radiologists was estimated by the Royal College of Radiologists in 2002 to:

Not surprisingly, perceived deficiencies were noted within the service. These included excessively long waiting times for complex examinations (including the DCBE) and radiological reports turned around too slowly to affect patient management, or not reported at all (Audit Commission, 1995). The DCBE examinations were often single reported, even when double reporting was considered to be best practice (Markus et al., 1990; Leslie and Virjee, 2002; Halligan et al., 2003). This raised serious concerns for patient care and the impact upon their prognoses, particularly where cancer was suspected. The shortage of radiologists also inevitably held back the further development of the service at that time, with less time available for audit, research and the introduction of new services.

A possible solution

Radiographers had expanded their pre-registration education to degree level (from a 2-year diploma course) and experienced radiographers had begun to explore postgraduate master’s level opportunities. Radiographers have long been perceived to be working below their potential (Swinburne, 1971), often moving into managerial or education positions due to a lack of challenging opportunities in clinical practice. One solution, to train radiographers to undertake DCBE examinations, as these had unacceptably long waiting lists in many hospitals, offered an important new challenge and yet could be ‘easily described within a protocol’ (Somers et al., 1981).

A legal framework within which to introduce the change

A number of changes to legislation and professional body guidance was introduced within the 1990s, some acting as a catalyst to encourage role development and some, inevitably, being brought about in response to what was already happening at a local level. These included the introduction of the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations (Department of Health, 2000a) and Department of Health publications such as the NHS Cancer Plan (2000b). The professional body and trade union for radiographers (the Society and College of Radiographers) was very supportive to radiographers wishing to develop their roles, issuing a series of guidance documents between 1996 and the present day (e.g. The College of Radiographers 1996, 1997, 2006). In essence, these documents suggested a framework in which radiographers could potentially develop any role, as long as they were appropriately trained, worked within agreed protocols, audited their practice and maintained their competence through continuing professional development (CPD). Protocols have been found to be appropriate frameworks within which radiographers can safely and effectively practice advanced roles (Nightingale, 2008). The Royal College of Radiologists (RCR; the UK radiologists’ professional body) has also been supportive towards radiographer role development, although with a slightly more cautious approach (RCR 1996, 1999, 2007). This is understandable when their members are delegating existing tasks and may still bear the ultimate responsibility for the delegated role.

A ‘champion’ of the change, at national and local level

There has to date been no direct professional body steer to introduce a particular role development across the UK. However, as with most new roles, there is often a champion at national level. For the introduction of radiographer-performed DCBE, this champion has arguably been the national gastrointestinal radiographers’ special interest group (GIRSIG), which has both promoted and supported radiographers involved in these roles for several years (Nightingale and Hogg, 2000). However, it is not clear if the role would have been introduced so successfully across the UK if it had not been for the presence of radiologist champions, promoting radiographer role development both within and beyond radiology (e.g. Chapman, 1997; Robinson et al., 1999; Thomas, 2005b). The radiologists appeared at that time to be the ‘gatekeepers’ to service development and this largely appears to be the case today. The radiologists provided clinical training and supervision for the radiographers, who had access to a short course or Master’s level module for theoretical underpinning.

National drivers for role development have also emerged in the wake of a series of government targets, most notably the introduction of a maximum waiting target of 2 weeks from referral to diagnosis for suspected cancer (NHS Executive, 2000) and, more recently, the 18 week maximum from referral to treatment (Department of Health, 2006). With medical imaging being heralded by the Government as the primary bottleneck resulting in failure of hospitals to meet these targets (Department of Health, 2005), it is little wonder that modernizing services and new ways of working are being championed in political circles.

Evidence (research) that the change will be effective

Published evidence that the role change is effective is vital to promote the widespread introduction of a new service. While UK radiographers have been rather reticent to engage in research, where the DCBE examination has been concerned, one finds a wealth of literature supporting the new role. This has included a number of studies comparing radiographer performance in performing and/or reporting DCBE examinations with trainee radiologists (Mannion et al., 1995; Schreiber et al., 1996; Davidson et al., 2000) or with consultant radiologists (McKenzie et al., 1998; Culpan et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2002; Vora and Chapman, 2004). It also includes performance against pathology databases (Law et al., 1999, 2008) and national surveys of practice (Bewell and Chapman, 1996). While most of these studies have concentrated on small numbers of individuals in single-center studies, they nevertheless provide very useful and plausible performance data across large numbers of patients.

A benefit to stakeholders (interested parties)

However, without there being a clear benefit to the relevant stakeholders, it is unlikely that a new role will be introduced. The benefits to radiology departments have been clear, with vastly reduced waiting lists for DCBE and, where radiographer reporting has been introduced, quicker turnaround for report writing. There are potential cost savings, with the hourly rate of a radiographer being considerably less than that of a consultant radiologist (Brown and Desai, 2002). Surprisingly little published literature is focused upon patient acceptability, although in practice many unpublished patient surveys have suggested that patients are happy to be cared for by a radiographer without recourse to a radiologist. The patient benefits directly from these improvements, reducing anxiety with shorter waits and having a potentially better prognosis associated with a shortened referral to diagnosis timeframe. The benefits to the radiologist are clear, in that they have more time to fulfil their other duties or to introduce new services. Anecdotal evidence would suggest that, for most radiologists, the rather unglamorous aspects of the DCBE procedure have not been missed from their portfolio of duties!

Beyond the DCBE

The radiographer-performed DCBE role has been so well received that radiographer-led services are now the norm across the UK National Health Service (NHS), with recent estimates suggesting that over 1200 radiographers have been trained to perform DCBE (Nightingale and Hogg, 2007); 82% of hospitals surveyed by Price and Le Masurier (2007) had implemented a radiographer-led DCBE service. Many such radiographers have gone on to undertake postgraduate training to enable them to write an official report on the DCBEs, with published data supporting this practice (Law et al., 1999; Murphy et al., 2002). While most of the available courses prepare and assess radiographers to report independently, in practice, many will report as part of a double reporting system, whereby two people view the images independently and then compare reports. Double reporting is recommended in the UK for the DCBE procedure, as it is associated with a high level of potential perception errors (Markus et al., 1990; Leslie and Virjee, 2002).

Some radiographers have further expanded their role to perform and report barium swallows and meals, videofluoroscopy swallowing assessments, small bowel studies, proctograms and other non-GI fluoroscopy (e.g. hysterosalpingography) (Law et al., 2005; Nightingale and Mackay, 2009). While most DCBE radiographers have further developed their role within the confines of the fluoroscopy room, increasingly GI radiographers are crossing traditional imaging modalities to run a CT colonography service, often in conjunction with a CT radiographer. Some are not only working across imaging modalities, but have also crossed professional boundaries to work with teams outside radiology. Although nurse-performed endoscopy is far more common (Maruthachalam et al., 2006, Kelly et al., 2007), a handful of UK radiographers have trained to undertake sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, with the potential advantage over nurses of being able to offer continuity of care with combined DCBE and direct visualization on one day.

However, despite the exciting opportunities presented, relatively few UK radiographers have developed their role beyond the DCBE examination (Price and Le Masurier, 2007). This may be because the required drivers for effective role changes (see Box 1.1.) are not firmly in place. In Table 1.1, we present possible reasons, based upon both published and anecdotal evidence, regarding the apparent stalemate in the adoption of further role developments and advanced practices.

Table 1.1 Criteria for effective implementation of role changes beyond the DCBE examination since 2000

| Driver for change | Evidence for the presence of the driver |

|---|---|

| A perceived deficiency in the service |

Clearly from Table 1.1, a number of drivers for effective implementation of widespread role changes are not currently in place. While a clear service need for other GI advanced practices may exist within any given hospital, the role is unlikely to be adopted as national standard practice without there being a perceived service deficiency, coupled with a champion at national level.

At the time of writing, it appears that we are once again on the threshold of a new role change for radiographers, which may well be implemented on a national basis. CT colonography (CTC) (alternatively known as virtual colonoscopy), a relatively new technique to examine the bowel, has been extensively researched around the world. Advocates of this procedure are proposing that it will eventually replace the barium enema for symptomatic work and may have an important role to play in bowel screening. For this reason, the government and professional bodies have also taken a keen interest, with a national working party currently developing a framework for implementation. A UK wide study (SIGGAR 1 trial) comparing CTC to barium enema and colonoscopy for bowel cancer in older symptomatic patients is soon to report its findings (Halligan et al., 2007). Nevertheless, hospitals around the UK have already introduced this procedure to varying degrees, with many proposing that radiographers play an important part in both performing the procedure, managing the scanning protocols and, in some way, contributing to the reporting process. Table 1.2 considers the presence or absence of drivers for implementation of radiographer involvement in CTC.

Table 1.2 Criteria for effective implementation of radiographer role development in CTC, as of 2008

| Driver for change | Evidence for the presence of the driver |

|---|---|

| A perceived deficiency in the service | |

| A proposed solution |

Radiographers who currently perform DCBE examinations already have many transferable skills for performing the procedure (e.g. rectal catheterization and IV cannulation)

Radiographers skilled in CT have the expertise to manage the CT examination, and may be skilled in IV cannulation

|

| A legal framework within which to introduce the change | Supportive to role developments |

| A ‘champion’ of the change, at national and local level | |

| Evidence (research) that the change will be effective | Whilst there is a lot of evidence to support CTC, limited data is found regarding the radiographer role |

| A benefit to stakeholders (interested parties) |

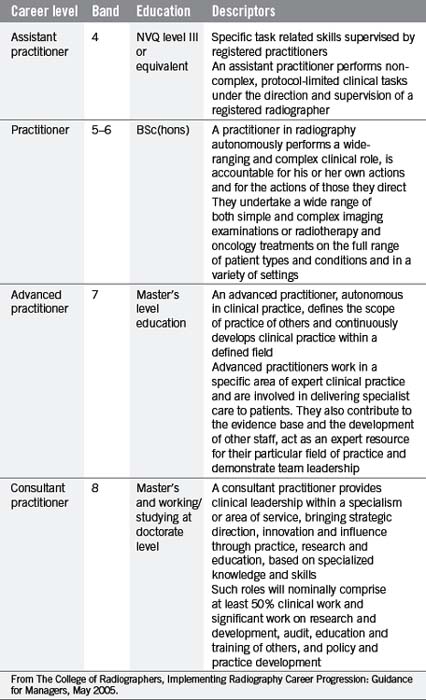

While CTC presents an exciting opportunity for radiographers (and possibly radiology nurses) to expand their role beyond the DCBE, a number of radiographers have already developed a ‘package’ of expertise that has enabled them to attain the highest level of clinical speciality in the UK – that of consultant radiographer status. At the time of writing, there are 26 consultant radiographers in the UK, five being GI sub-specialists. While the ethos of the consultant practitioner role should be applauded, 5 years since their introduction the actual numbers achieving this accolade are still woefully low (Price and Le Masurier, 2007). Their roles vary depending upon local needs, but predominantly their post is concerned with service development, including aspects of expert clinical practice, research and involvement in education (College of Radiographers, 2005). They often work alongside GI advanced practitioners, radiographer practitioners, assistant practitioners and radiology nurses within the GI service (see Table 1.3), with several crossing professional boundaries to work within the gastroenterology or endoscopy departments. It is likely that the numbers of advanced and consultant GI practitioners will grow in the next few years, although funding such posts will always be a major issue.

Inevitably, the role of the radiologist will also continue to evolve, with medical imaging always being central to clinical medicine. However, it is likely that, similar to the situation within radiography, radiologists will continue to specialize to ensure they can provide the best care for their patients and will need to introduce innovative solutions to respond to changing patterns of care, including a move towards a 24/7 department and increasing opportunities in molecular imaging (Thomas, 2005a).

International perspectives

Having outlined the historical and current situation in the UK, we will now consider how these compare to shifting professional boundaries within selected other countries, and will attempt to ascertain why any differences exist. Cowling (2008) offered a global overview of the changing roles of radiographers, suggesting that the UK has led the way in widening their scope of practice and is unquestionably the world leader in advanced practice. She outlines four different levels of role advancement, with the UK and the USA being in the first tier, having implemented an effective system of role advancement. In the second level lie countries such as Australia and New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and Japan, where the driving forces are the same but implementation has not yet happened to any great degree. The third level countries have made moves towards having formal recognition for their profession, with role development being their next step, and the fourth group have yet to achieve formal acceptance of radiography as a distinct profession. The situation in the USA, Australia and New Zealand will now be explored further in terms of gastrointestinal imaging role advancements and will be compared to that of the UK.

The United States of America

In the USA, the practice of GI radiography varies widely from state to state. In some states, radiographers are able to perform many examinations independently, while in other parts of the country radiographers are limited to more of an assistant’s role. There are few national statutes regulating the practice of GI radiography, however, the American Society of Radiologic Technologists (ASRT) has developed practice standards and the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists (ARRT) designed a task inventory that provides general guidance to radiographers in the performance of GI exams (ASRT, 2007a; ARRT, 2004). These principles would be further defined by the individual states, whose law supersedes those of the national Societies.

The radiographer’s role in a majority of these studies is to assist the radiologist during the fluoroscopic portion of the exam and perform any additional over-couch follow-on images independently. The most notable exception to the role of the radiographer compared to the situation in the UK is results reporting. Fluoroscopy can be performed by a radiographer, as long as there is no reporting connected to the procedure (ASRT, 2007a).

The additional role of the RA was developed for several reasons: to provide a career ladder for radiographers; to increase the job satisfaction of radiographers; to reduce radiographer attrition; to address the radiologist shortage; to increase efficiency; and to reduce expenses (Smith and Applegate, 2004; McLeod and Montane, 2006; Carlos and Keast, 2006). These drivers for change are not dissimilar to those culminating in role developments within the UK. The concept of a radiologist assistant was also developed because there was a wide acceptance that properly trained radiographers could perform specific examinations independently. Arguably, the area of imaging identified where RAs could make the greatest impact was in GI imaging. Several studies performed in the USA indicate that properly trained radiographers can perform fluoroscopic GI examinations to a level comparable to radiology residents (Schreiber et al., 1996; Davidson et al., 2000) and, in some cases, even practicing radiologists (Van Valkenburg et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2006).

In their new roles, radiologist assistants are able to perform an expanded array of procedures in GI radiology and the ASRT and ARRT have consequently expanded the guidelines for RAs, allowing them to perform many examinations with some degree of independence. According to the ARRT’s (2005) Registered Radiologist Role Delineation, RAs may perform the following GI procedures without the physical presence of the radiologist in the room (although they must be immediately available for consultation if necessary):

Although the exam can be performed by the RA and preliminary findings can be reported to the radiologist, the RA is still prevented from rendering a final diagnostic reading of the images (ASRT, 2007b). Similar to the ‘Red Dot’ system utilized in other countries, the RA may strictly point out areas of concern for the radiologist but the final report is approved by a board certified radiologist. This limitation imposed upon radiographers is perhaps understandable while these new roles are in their infancy, particularly in the absence of published literature supporting radiographer reporting in the GI field. However, one approach strongly advocates that the person undertaking a dynamic, real-time examination is in the best position to write a diagnostic report on the findings, as they have been party to the fluoroscopic findings which may not have all been captured on static images (Halligan et al., 2003). Perhaps the fact that the USA operates a fee per service system (including the report) may influence the professional latitude awarded to the radiographers. Within the UK National Health Service, a fee per service system does not affect the pay and awards of an individual radiologist. However, over time, it may be possible to develop the radiographers’ reporting skills to enable them to contribute fully to a double reporting system, where they write the report, which is then verified by the radiologist.

By November 2007, there were 59 radiologist assistants who had graduated from 10 educational programmes (May et al., 2008). Early evaluations showed that there was the potential to save radiologists an average of 100 minutes per day, with a resultant cost saving, even though RA salaries are some 62% higher than radiographers (Wright et al 2008). Based on evidence such as this, radiologist support for the RA program is growing (May et al., 2008).

Australia and New Zealand

It may be considered that Australia is perhaps somewhere in the order of 20 years behind the UK in the area of radiographer role development. In comparison to the UK, Australia is a very large country with a number of states that act as their own governors; thus regulations vary from state to state. Most imaging services are delivered within private radiology groups, some operating in very remote places. While a limited extension of the scope of practice is occurring in small pockets around Australia (e.g. IV cannulation, contrast injections and Red Dot flagging), it has normally come about through approval at hospital level as a result of local need, rather than as part of a coordinated national approach (Smith et al., 2008). In Australia, there is currently little radiographer involvement in GI procedures beyond acting in an ‘assistant to the radiologist’ capacity, although in New Zealand, two radiographers are currently performing DCBE examinations.

The topic of radiographer role development is gathering momentum, however, with a continuing shortfall of radiologist numbers required for timely service delivery, coupled with an increase in the demand for imaging services in light of technological evolution and the aging population (Smith and Baird, 2007). Journal and press articles raising awareness and concern are increasing in number, detailing reporting backlogs, unmet service demands and associated risks regarding patient welfare and diagnostic outcomes (Patty, 2007). In New Zealand, a high rate of colorectal cancer, coupled with difficulties in providing a responsive service in some of the more remote areas, would seem to be potential catalysts for future radiographer-led GI services. However, the current fee for service system seems to work against radiologists delegating the examinations and, in particular, the reporting aspects, to radiographers. As has been evident in both the UK and the USA, the radiologists continue to be the gatekeepers to the role development of radiographers.

The Productivity Commission’s Health Workforce Report of 2005 (Productivity Commission, 2005) examined the impact on healthcare services taking into account the supply and demand of trained health practitioners, and the current workforce’s ability to meet service demands. As has already been established in other countries, the question of limited task transfer in some professions within Australia has been identified as holding the key to alleviating some of the current stress (Smith and Baird, 2007). To date, an advanced practice model has been developed and implemented within the Australian Nursing Profession.

The Australian Institute of Radiography (AIR) is Australia’s leading national body representing radiographers, radiation therapists and sonographers. In anticipation of the escalation of this mis-match of supply, demand and increased patient risk, AIR is actively working towards implementation of an advanced practice model to suit the Australian workforce environment. The AIR is simultaneously negotiating with the Australian government and with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR) to propose a new hierarchical structure that includes an advanced practitioner tier. RANZCR’s position, in a similar stance to that of the USA professional organizations, is that a radiological report cannot at this time be provided by anyone who is not a trained medical practitioner and who has not subsequently undergone training as an imaging specialist (Kenny and Andrews, 2007).

In New Zealand, however, the previously ‘ad hoc’ role developments have gained national interest, culminating in working groups specifically set up to look at the future skills mix in radiology departments. Reports from both the New Zealand Institute of Medical Radiation Technology (NZIMRT) and the District Health Boards of New Zealand were due to be published in 2008. The NZIMRT has approved a recommendation to introduce a three-tier career framework, including assistant practitioners, practitioners and advanced practitioners. It is anticipated that the first advanced practice roles will be introduced before the end of 2008 (Smith et al., 2008).

Summary

While the scope of practice of the radiographer has gradually expanded, the practice of GI imaging has evolved rapidly at the same time. Conventional radiography and fluoroscopy, once the foundation of GI imaging, are quickly being replaced by other imaging modalities. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the GI tract and flexible sigmoidoscopy have become commonplace in the USA and the UK. Even magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is beginning to compete for GI patients (Goldberg and Margulis, 2000; Tait and Allison 2001). Although there will probably always be a need for fluoroscopic imaging where function is a concern, the acquisition of cross-sectional images via CT, MR, ultrasound and hybrid imaging (such as PET-CT) will be likely to reduce the number of conventional fluoroscopic procedures being performed in the future. It is therefore even more critical that radiographers strive to develop and maintain their competence in GI imaging so that when they are involved in GI examinations they are up to the challenge.

American Registry of Radiologic Technologists. Registered radiologist assistant role delineation. 2005. Online http:/ /www.arrt.org/radasst/finalraroledelineation.pdf 10 Nov 2007

American Registry of Radiologic Technologists. Task inventory for radiography. 2004. Online http:/ /www.arrt.org/examinations/practiceanalysis/radti2005.pdf 10 Nov 2007

American Society of Radiologic Technologists. The practice standards for medical imaging and radiation therapy. 2007. Online. http:/ /www.asrt.org/media/pdf/standards_rad.pdf 10 Nov 2007

American Society of Radiologic Technologists. Radiologist Assistant Practice Standards. 2007. Online http:/ /www.asrt.org/media/pdf/practicestds/GR06_OPI_RA_Stnds_Adpd.pdf 10 Nov 2007

Audit Commission. Improving your image – how to manage radiology services more effectively. London: HMSO, 1995.

Australian Institute of Radiography. Professional advancement working party report. 2006. Online. http:/ /www.ar.com.au/documents/PAWP_Report_Final_April06.pdf 4 Dec 2007

Bewell J., Chapman A.H. Radiographer-performed barium enemas – results of a survey to assess progress. Radiography. 1996;2:199-205.

Brown L., Desai S. Cost-effectiveness of barium enemas performed by radiographers. Clin. Radiol.. 2002;57(2):129-131.

Carlos R.C., Keast K.C. Radiology physician extenders and their perspective in their own words. J. Am. Coll. Radiol.. 2006;3:190-193.

Chapman A.H. Changing work patterns. Lancet. 1997;350:581-583.

Cowling C. A global overview of the changing roles of radiographers. Radiography. 2008. (Supplement 1) e28–e32

Culpan D.G., Mitchell A.J., Hughes S., et al. Double contrast barium enema sensitivity: a comparison of studies by radiographers and radiologists. Clin. Radiol.. 2002;57:604-607.

Davidson J.C., Einstein D.M., Baker M.E., et al. Feasibility of instructing radiology technologists in the performance of gastrointestinal fluoroscopy. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2000;175(5):1449-1452.

Department of Health. NHS takes next step in tackling hidden waiting lists. 2006. Press release, reference no. 2006/0072, 21 February 2006, accessed online on 06/05/06 at www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/PressReleases.htm

Department of Health. Quicker scans, endoscopies and imaging for NHS patients. £1 billion to tackle hidden diagnostic waits – Reid, Press releases. 2005. Saturday 19 February 2005 Reference number: 2005/0064

Department of Health. Ionising radiation (medical exposure) regulations. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Department of Health. The National Health Service Cancer Plan. Department of Health, London, 2000. http:/ /www.doh.gov.uk/cancer/cancerplan.htm#.

Goldberg H.I., Margulis A.R. Gastrointestinal radiology in the United States: an overview of the past 50 years. Radiology. 2000;216:1-7.

Halligan S., Lilford R.J., Wardle J., et al. Design of a multicentre randomized trial to evaluate CT colonography versus colonoscopy or barium enema for diagnosis of colonic cancer in older symptomatic patients: the SIGGAR study. Trials. 2007;8:32.

Published online, 2007. October 27. doi: 10.1186/1745–6215–8–32.

Halligan S., Marshall M., Taylor S., et al. Observer variation in detection of colorectal neoplasia on barium enema: implications for colorectal cancer screening and training. Clin. Radiol.. 2003;58:948-954.

Kelly S.B., Murphy J., Smith A., et al. Nurse specialist led flexible sigmoidoscopy in an outpatient setting. Colorectal Dis.. 2007. 2007 May 17; [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 17509042 [PubMed – as supplied by publisher]

Kenny L.M., Andrews M.W. Addressing radiology workforce issues. Med. J. Aust.. 2007;186:615-616.

Law R.L., Longstaff A.J., Slack N. A retrospective 5-year study on the accuracy of the barium enema examination performed by radiographers. Clin. Radiol.. 1999;54(2):80-83. discussion 83–84

Law R.L., Slack N., Harvey R.F. An evaluation of a radiographer-led barium enema service in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Radiography. 2008. 14(2), 105–110

Law R.L., Slack N., Harvey R.F. Radiographer performed single contrast small bowel enteroclysis. Radiography. 2005;11(1):11-15.

Leslie A., Virjee J.P. Detection of colorectal carcinoma on double contrast barium enema when double reporting is routinely performed: an audit of current practice. Clin. Radiol.. 2002;57:184-187.

Mannion R.A., Bewell J., Langan C. A barium enema training programme for radiographers: a pilot study. Clin. Radiol.. 1995;50(10):715-718. discussion 718–719

Markus J.B., Somers S., O’Malley B.P., et al. Double-contrast barium enema studies: effect of multiple reading on perception error. Radiology. 1990;175:155-156.

Maruthachalam K., Stoker E., Nicholson G., et al. Nurse led flexible sigmoidoscopy in primary care – the first thousand patients. Colorectal Dis.. 2006;8(7):557-562.

May L., Martino S., McElveny C. The establishment of an advanced clinical role for radiographers in the United States. Radiography. 2008. 14 (Supplement 1), e24–e27.

McLeod D., Montane G. The radiologist assistant: the solution to radiology workforce needs. Emerg. Radiol.. 2006. Online http:/ /www.springerlink.com/content/7746t77h73133215 10 Nov 2007

McKenzie G.A., Mathers S., Graham D.T., et al. An investigation into radiographer-performed barium enemas. Radiography. 1998;4:17-22.

Murphy M., Loughran C.F., Birchenough H., et al. A comparison of radiographer and radiologist reports on radiographer conducted barium enemas. Radiography. 2002;8:215-221.

NHS Executive. Cancer Referral Guidelines, Health Service Circular, HSC 2000/013. 2000 www.doh.gov.uk/coinh.htm Accessed online 06/05/06

Nightingale J. Developing protocols for advanced and consultant practice. Radiography. 2008. 14 (Supplement 1), e55–e60

Nightingale J., Hogg P. The role of the GI radiographer: a UK perspective. Radiol. Technol.. 2007;78(4):1-7. March/April 2007

Nightingale J., Hogg P. The gastrointestinal advanced practitioner: an emerging role for the modern radiology service. Radiography. 2003;9:151-160.

Nightingale J., Hogg P. Clinical practice at an advanced level: an introduction. Radiography. 2003;9:77-83.

Nightingale J., Hogg P. Gastro-intestinal imaging for radiographers: current practice and future possibilities. Synergy. 2000:16-19.

Nightingale J., Mackay S. An analysis of changes in practice introduced during an educational programme for practitioner-led swallowing investigations. Radiography. 2009. 15 (1), 63–69

Patty A.. X-ray backlog: patients at risk, Sydney Morning Herald 6 Oct 2007. 2007. Online. http:/ /www.smh.com.au 2 Dec 2007

Price R.C., Le Masurier S.B. Longitudinal changes in extended roles in radiography: a new perspective. Radiography. 2007;13(1):18-29.

Productivity Commission Research Report. Australia’s Health Workforce. Canberra. 2005. Online. http:/ /www.pc.gov.au 5 Dec 2007

Robinson P.J.A., Culpan G., Wiggins M. Interpretation of selected accident and emergency radiographic examinations by radiographers: a review of 11 000 cases. Br. J. Radiol.. 1999;72:546-551.

Schreiber M.H., van Sonnenberg E., Wittich G.R. Technical adequacy of fluoroscopic spot films of the gastrointestinal tract: comparison of residents and technologists. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1996;166(4):795-797.

Smith T., Yielder J., Ajibulu, et al. Progress towards advanced practice roles in Australia, New Zealand and the Western Pacific. Radiography. 2008.

Smith T.N., Baird M. Radiographers’ role in radiological reporting: a model to support future demand. Med. J. Aust.. 2007;186:629-631.

Smith W.L., Applegate K.E. The likely effects of radiologist extenders on radiology training. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2004;1:402-404.

Somers S., Stevenson G.W., Laufer I., et al. Evaluation of double contrast barium enemas performed by radiographic technologists. J. Can. Assoc. Radiol. 1981;32(4):227-228.

Swinburne K. Pattern recognition for radiographers. Lancet. 1971:589-590.

Tait P., Allison D. Imaging of the gastrointestinal tract. Drugs Today. 2001;37(8):533-557.

The College of Radiographers. Medical image interpretation and clinical reporting by non-radiologists: the role of the radiographer. London: COR, 2006.

The College of Radiographers. Reporting by radiographers: a vision paper. London: The College of Radiographers, 1997.

The College of Radiographers. Role development in radiography. London: The College of Radiographers, 1996.

The Royal College of Radiologists/The Society and College of Radiographers. Team working within clinical imaging – a contemporary view of skills mix. London: Joint guidance from the Royal College of Radiologists and the Society and College of Radiographers, 2007.

The Royal College of Radiologists. Clinical radiology: a workforce in crisis. London: The Royal College of Radiologists, 2002. BFCR (02) 01

The Royal College of Radiologists. Skills mix in clinical radiology. London: The Royal College of Radiologists, 1999. BFCR (99)3

The Royal College of Radiologists. Advice on delegation of tasks in departments of clinical radiology. London: The Royal College of Radiologists, 1996.

The Society and College of Radiographers. Implementing radiography career progression: guidance for managers. London: The Royal College of Radiologists, 2005.

Thomas A. The role of the radiologist in 2010. Imaging and oncology 2005. London: The College of Radiographers, 2005.

Thomas N. A radiologist’s perspective. In: McConnell J., Eyres R., Nightingale J., editors. Interpreting trauma radiographs. Oxford: Blackwell Publications; 2005:7-18.

Thompson W.M., Foster W.L., Paulson E.K., et al. Comparison of radiologists and technologists in the performance of air-contrast barium enemas. Am. J. Radiol.. 2006;187:706-709.

Van Valkenburg J., Ralph B., Lopatofsky L., et al. The role of the physician extender in radiology. Radiol. Technol.. 2000;72(1):45-50.

Vora P., Chapman A. Complications from radiographer-performed double contrast barium enemas. Clin. Radiol.. 2004;59:364-368.

Wright D.L., Killion J.B., Johnston J., et al. RAs increase productivity. Radiol. Technol.. 2008;79(4):365-370.