CHAPTER 1 Evolution of Shoulder Arthroplasty

FIRST SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

Although Jules Emile Péan is credited with performing the first shoulder arthroplasty, it was probably Themistocles Gluck who first recognized prosthetic replacement as a potential treatment option in the shoulder.1 Gluck, a Romanian who studied in Germany in the second half of the 19th century, pioneered joint replacement for the treatment of tuberculosis infection. Gluck reported on his design of an ivory shoulder replacement but never documented its use in a living human subject.

The first recorded shoulder arthroplasty was performed in 1893 by Péan, a Parisian surgeon who replaced the shoulder of a patient suffering from tuberculous arthropathy who had refused amputation.2 Péan implanted a shoulder prosthesis designed and constructed by J. Porter Michaels, a Parisian dentist; the prosthesis consisted of a rubber humeral head that had been boiled in paraffin to harden it and was attached to a platinum shaft via a metal wire. A second metal wire attached the implant to the glenoid. The patient initially “did well” after the surgery before ultimately requiring removal of the prosthesis for recurrence of infection 2 years later.

FIRST-GENERATION SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

The first shoulder arthroplasty using a prosthesis with an anatomic design was performed in 1950 by Frederick Krueger.3 Krueger used a Vitallium implant created by molding proximal humeri obtained from cadavers. He successfully implanted this prosthesis in a young patient with osteonecrosis of the humeral head. The modern era of shoulder arthroplasty, however, was pioneered by Dr. Charles Neer. Neer originally performed hemiarthroplasty to treat complex proximal humeral fractures starting in 1953.4 Nearly 20 years later he would report on the use of shoulder replacement for the treatment of glenohumeral arthritis.5 Neer originally used a monoblock implant; however, variations in humeral head size among patients led to the concept of modularity, which allowed the use of variable humeral head diameters in shoulder arthroplasty. Monoblock implants are now commonly referred to as first-generation shoulder arthroplasty.

THIRD-GENERATION SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

In the late 1980s Boileau and Walch hypothesized that variations in anatomy prevented current first- and second-generation shoulder arthroplasty stems from achieving optimal fit within the proximal humerus.6 They undertook an anatomic study of the proximal humerus that yielded some important conclusions. They discovered that the proximal humerus could be modeled by using a sphere and cylinder. A portion of the sphere represents the articular surface of the proximal humerus. The diameter of the humeral head articular surface was found to be highly variable, as was the thickness of the humeral head. Thickness and diameter were found to have a fixed relationship and correlated with one another linearly. They further found the inclination of the anatomic neck of the humerus relative to the humeral diaphysis to be highly variable. Humeral retroversion, defined by the relationship of the humeral anatomic neck to the transepicondylar axis of the elbow, was found to vary by more than 50 degrees. Finally, the sphere (humeral head) was discovered to be offset, usually posteriorly and medially, from the cylinder (humeral diaphysis). These relationships are summarized in Table 1-1.

| Rights were not granted to include this data in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book. |

Several laboratory studies have demonstrated the clinical relevance of advances in design imposed by third-generation humeral implants. Harryman and colleagues demonstrated how placing too thick a humeral component had detrimental effects on glenohumeral motion,7 whereas Jobe and Iannotti found a decrease in the arc of available glenohumeral motion when using too thin a humeral head component.8 In an eloquent computer model, Pearl and Kurutz demonstrated the necessity of being able to vary the humeral head diameter, humeral head offset, and neck inclination angle of a humeral prosthesis to replicate the patient’s native anatomy (Fig. 1-1).9

GLENOID RESURFACING

Neer first reported on the use of a glenoid component in unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of glenohumeral arthritis in 1974.5 Neer’s original implant was a keeled cemented rectangular component (the same anterior-to-posterior diameter superiorly and inferiorly) with a radius of curvature matching the humeral head component.

Advances in glenoid resurfacing have occurred in component design and implantation techniques. Different component designs commonly used include cemented polyethylene keeled convex-back designs, cemented polyethylene keeled flat-back designs, cemented polyethylene pegged convex-back designs, and metal-backed designs. Convex-back designs have been shown experimentally to resist sheer forces better than flat-back designs do, and this has translated into fewer radiolucent lines around the glenoid component in the clinical scenario.10–12 The larger debate exists over whether to use a keeled or a pegged component. Laboratory studies have demonstrated less micromotion with pegged implants.13 Clinical studies, however, have reported both the superiority of pegs and the superiority of keels.14,15 Because radiographic comparison of these two types of implant is difficult, this debate remains unsolved at present. The original metal-backed designs consisted of a metal base plate secured with a screw-type mechanism and a modular polyethylene liner. The thickness of the metal often required that the polyethylene insert be very thin to avoid placing excessive tension on the gleno humeral soft tissues. This thinness resulted in poor wear characteristics of the polyethylene and caused implant failure.16 Many early metal-backed designs have been abandoned; however, implantation of a glenoid component without the use of cement is still appealing, especially in revision surgery, which may involve compromised glenoid bone stock. Research is ongoing in the development of new and improved metal-backed glenoid designs.

One of the most recent and significant advances in glenoid component design is recognition of the significance of glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch. Mismatch is defined as the difference in radius of curvature between the humeral head and glenoid component. Congruent articulations (mismatch = 0) allow optimal surface contact, minimize the risk of surface wear of the glenoid component, and contribute to increased joint stability. However, with these advantages comes a lack of obligate translation (translation between the articular surfaces that normally occurs with shoulder mobility and is absorbed by elastic deformation of the articular cartilage and the glenoid labrum). Lack of obligate translation may lead to loosening of the glenoid component by increasing the stress developed at the implant fixation site. Alternatively, noncongruent articulations (larger glenoid than humeral radius of curvature) allow obligate translation between the humeral head and the glenoid, thereby potentially decreasing the stress observed at the glenoid implant fixation site. Glenoid component wear and joint stability remain a concern in noncongruent articulations. Laboratory investigations have yielded some insight into appropriate mismatch in shoulder arthroplasty, including studies demonstrating that a 4-mm mismatch is necessary to best replicate normal shoulder mobility, and studies showing that mismatch in excess of 10 mm risks fracture of the polyethylene component.17,18 The clinical relevance of these laboratory studies was not clear, however, until Walch and coworkers reported on the influence of glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch on radiolucent lines occurring around the glenoid component.19 This study found that fewer radiolucent lines occurred at minimum 2-year follow-up when a radial mismatch of at least 6 mm was used during performance of total shoulder arthroplasty. An upper limit of mismatch was not established, however, thus prompting ongoing studies to discover the ideal glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch.

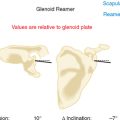

Another aspect of glenoid resurfacing that has evolved is the implantation technique of glenoid components. Neer originally recommended preparation of a keel slot with a curette to remove a large amount of bone and create a large cement mantle.5 More recently, Gazielly and colleagues introduced the bone compaction technique for implantation of keeled glenoid components.20 Radiolucent lines around glenoid components appear on the initial postoperative radiographs in many cases and have been attributed to technical deficiencies.21 The compaction technique of bone preparation addresses radiolucent lines in three ways. First, compaction of cancellous bone in the glenoid provides a more stable base for the glenoid component than does bone removal via curettage. Second, a compacted bone slot that has the same dimensions as the component keel allows a primary “press-fit” fixation that should help prevent micromotion of the component as the cement polymerizes. Third, the compaction technique uses a smaller amount of cement, which may decrease thermal necrosis of the adjacent glenoid bone. Clinically, a comparison of the curettage technique with the compaction technique has shown superiority of the compaction technique in minimizing radiolucent lines on immediate and 2-year postoperative radiographs.22

ARTHROPLASTY FOR FRACTURE

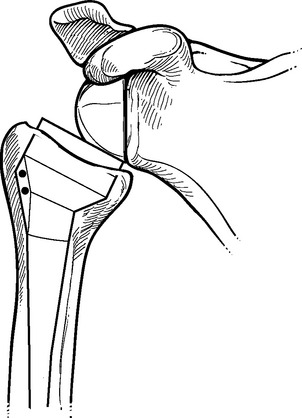

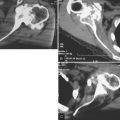

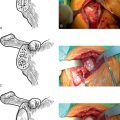

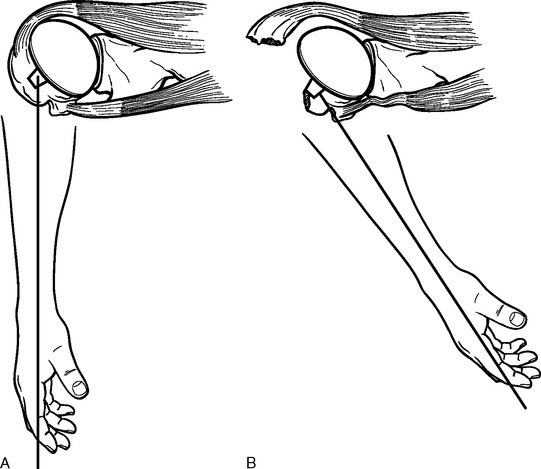

Neer’s original indication for shoulder arthroplasty—complex fractures of the proximal humerus—remains the most difficult diagnosis for which shoulder arthroplasty is used. Performance of shoulder arthroplasty for fracture is fraught with potential complications and often results in disappointing outcomes. The majority of these poor outcomes are related to nonunion or malunion of the greater and lesser tuberosities after arthroplasty. Boileau and associates have identified four potential causes of tuberosity complications after shoulder arthroplasty for fracture.23 First, improper positioning of the prosthesis may lead to nonunion of the tuberosities by placing undue tension on the rotator cuff, specifically if the prosthesis is implanted proud or in excessive retroversion (Fig. 1-2). Second, the osteopenic nature of the tuberosities in this patient population makes healing of the tuberosities difficult to achieve. Third, fixation of the tuberosities around the prosthesis is difficult, and passing sutures through holes in the prosthetic stem often results in suture breakage and migration of the tuberosities.24 Fourth, the large amount of proximal metal used in conventional humeral arthroplasties may act as a hindrance to healing of the tuberosities.

Figure 1-2 A and B, Illustration showing how excessive humeral retroversion can cause tuberosity migration.

Arthroplasty for fracture has evolved specifically to address these issues of tuberosity complications. First, ancillary instrumentation has been developed to allow more reliable placement and testing of the humeral implant before definitive cementation(Fig. 1-3). Second, the interface between the greater and lesser tuberosities and the interface between the tuberosities and the native humerus is routinely bone-grafted with autogenous bone from the fractured humeral head. Third, a reproducible, biomechanically stable tuberosity fixation technique has been developed that avoids passage of suture through a metallic implant. Fourth, new implants with less metallic bulk proximally and with metaphyseal fenestrations to promote healing of the tuberosities are available for use in fracture cases (Fig. 1-4). Boileau and colleagues reported on the clinical implications of the use of an arthroplasty system designed for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures and found that tuberosity complications decreased from 49% in procedures involving conventional hemiarthroplasty to 25% in procedures that used a hemiarthroplasty designed for fracture cases.23

CONSTRAINED AND SEMICONSTRAINED SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

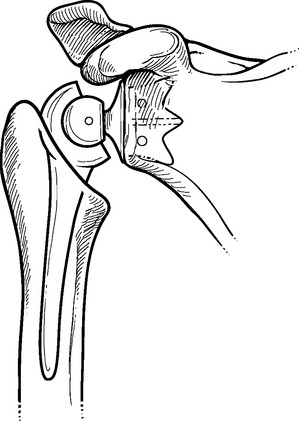

Constrained and semiconstrained arthroplasty were initially introduced in the 1960s to treat patients with glenohumeral arthritis and massive rotator cuff tears. The concept of these devices is to resolve upward migration of the humeral head and thereby restore the normal deltoid moment arm and allow active elevation of the arm powered by the deltoid. Reverse designs, with a sphere fixated to the glenoid and a cup secured to the proximal humerus, were introduced in the past to accomplish this goal. The problem with these early designs was early loosening of the glenoid caused by deltoid forces acting on the laterally offset center of glenohumeral rotation (Fig. 1-5). Such failures eventually resulted in abandonment of these early prosthetic designs.

Figure 1-5 The laterally located center of rotation of early reverse-design prostheses caused early loosening.

In 1987, Paul Grammont introduced a new reverse-design prosthesis in an effort to overcome the failures that had plagued earlier attempts. This new prosthesis uses a “glenosphere” component fixated over the scapular neck and places the center of glenohumeral rotation within the bone of the glenoid instead of lateral to it (Fig. 1-6).25 This prosthesis now has up to 15 years—follow-up in Europe, and glenoid failure rates have not exceeded those of unconstrained total shoulder prostheses in patients with a competent rotator cuff.26,27 Additionally, although pain relief has been equivalent to that seen with humeral head replacement, postoperative active shoulder elevation has far exceeded the elevation that can be expected after hemiarthroplasty.

1 Gluck T. Referat über die Durch das moderne chirurgishe Experiment gewonnenen positiven Resultate betreffend die Nacht und den Ersatz von defecten hoherer Gewebe sowie über die Verwertung resorbirbarer und lebendiger Tamons in der Chirurgie. Arch Klin Chir. 1891;41:187-239.

2 Lugli T. Artificial shoulder joint by Péan (1893). The facts of an exceptional intervention and the prosthetic method. Clin Orthop. 1978;133:215-218.

3 Krueger FJ. A Vitallium replica arthroplasty on the shoulder: A case report of aseptic necrosis of the proximal end of the humerus. Surgery. 1951;30:1005-1011.

4 Neer CS. Articular replacement for the humeral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37:215-228.

5 Neer CS. Replacement arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:1-13.

6 Boileau P, Walch G. Anatomical study of the proximal humerus: Surgical technique consideration and prosthetic design rationale. In: Walch G, Boileau P, editors. Shoulder Arthroplasty. Berlin: Springer; 1999:69-82.

7 Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, et al. The effect of articular conformity and the size of the humeral head component on laxity and motion after glenohumeral arthroplasty: A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:555-563.

8 Jobe CM, Iannotti JP. Limits imposed on glenohumeral motion by joint geometry. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:281-285.

9 Pearl ML, Kurutz S. Geometric analysis of commonly used prosthetic systems for proximal humeral replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:660-671.

10 Anglin C, Wyss UP, Pichora DR. Mechanical testing of shoulder prostheses and recommendations for glenoid design. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:323-331.

11 Lacaze F, Kempf JF, Bonnomet F, et al. Primary fixation of glenoid implants: An in vitro study. In: Walch G, Boileau P, editors. Shoulder Arthroplasty. Berlin: Springer; 1999:141-146.

12 Szabo I, Buscayret F, Walch G, et al: Radiographic comparison of flat back and convex back polyethylene glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty. Paper presented at the 16th Annual Meeting of the Société Européenne de Chirurgie de l’Epaule et du Coude, September 2002, Budapest.

13 Anglin C, Wyss UP, Nyffeler RW, Gerber C. Loosening performance of cemented glenoid prosthesis design pairs. Clin Biomech. 2001;16:144-150.

14 Gartsman GM, Elkousy HA, Warnock KM, et al. Radiographic comparison of pegged and keeled glenoid components. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:252-257.

15 Gazielly D, El-Abiad R. Comparative results of three types of polyethylene cemented glenoid components. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:483-488.

16 Boileau P, Avidor C, Krishnan SG, et al. Cemented polyethylene versus uncemented metal-backed glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty: A prospective, double-blind, randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:351-359.

17 Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Joint stability after total shoulder arthroplasty in a cadaver model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:506-511.

18 Friedman RJ, An YH, Draughn RA. Glenohumeral congruence in total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop Trans. 1997;21:17.

19 Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, et al. The influence of glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch on glenoid radiolucent lines: Results of a multicentric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:2186-2191.

20 Gazielly DF, Allende C, Pamelin E: Results of cancellous compaction technique for glenoid resurfacing. Paper presented at the 9th International Congress on Surgery of the Shoulder, May 2004, Washington, DC.

21 Brems J. The glenoid component in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2:47-54.

22 Szabo I, Buscayret F, Edwards TB, et al. Radiographic comparison of two different glenoid preparation techniques in total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;431:104-110.

23 Boileau P, Coste JS, Ahrens PM, Staccini P. Prosthetic shoulder replacement for fracture: Results of the multicentre study. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:561-578.

24 Gerber C, Wahlström P, Nyffeler R: Suture failure caused by suboptimal prosthetic design may cause secondary tuberosity displacement. Paper presented at the 8th International Congress on Surgery of the Shoulder, April 2001, Cape Town, South Africa.

25 Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics. 1993;16:65-68.

26 Favard L, Nové-Josserand L, Levigne C, et al: Anatomical arthroplasty versus reverse arthroplasty in treatment of cuff tear arthropathy. Paper presented at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Société Européenne de Chirurgie de l’Epaule et du Coude, September 2000, Lisbon, Portugal.

27 Bouttens D, Nérot C: Cuff tear arthropathy: Mid term results with the delta prosthesis. Paper presented at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Société Européenne de Chirurgie de l’Epaule et du Coude, September 2000, Lisbon, Portugal.