Chapter 147 Evaluation of Suspected Rheumatic Disease

Symptoms Suggestive of Rheumatic Disease

Arthralgias are common in childhood and are a frequent reason for referral to pediatric rheumatologists. Arthralgias without physical findings for arthritis suggest infection, malignancy, orthopedic conditions, benign syndromes, or pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia (Table 147-1). Although rheumatic diseases may manifest as arthalgias, arthritis is a stronger predictor of the presence of rheumatic disease and a reason for referral to a pediatric rheumatologist. The timing of joint pain along with associated symptoms including poor sleep and interference with normal activities provides important clues. Poor sleep, debilitating generalized joint pain that worsens with activity, school absences, and normal physical and laboratory findings in an adolescent suggest a pain syndrome (e.g. fibromyalgia). If arthralgia is accompanied by a history of dry skin, hair loss, fatigue, growth disturbance, and/or cold intolerance, testing for thyroid disease is merited. Nighttime awakenings due to severe pain along with decreased platelet count or white blood cell count or, alternatively, a very high white blood cell counts may lead to the diagnosis of malignancy, especially marrow-occupying lesions such as acute lymphocytic leukemia and neuroblastoma. Pain with physical activity suggests a mechanical problem such as an overuse syndrome or orthopedic condition. An adolescent girl presenting with knee pain aggravated by walking up stairs and on patellar distraction likely has patellofemoral syndrome. Children aged 3 to 10 yr who have a history of episodic pain that occurs at night after increased daytime physical activity and that is relieved by rubbing but who have no limp or complaints in the morning likely have growing pains. There is often a positive family history for growing pains, which may aid in this diagnosis. Intermittent pain in a child, especially a girl aged 3 to 10 yr, that is increased with activity and is associated with hyperextensible joints on exam is likely benign hypermobility syndrome. Many febrile illnesses cause arthralgias that improve when the temperature normalizes, and arthralgias are part of the diagnostic criteria for acute rheumatic fever (ARF; Chapter 176.1).

| SYMPTOM | RHEUMATIC DISEASE(S) | POSSIBLE NONRHEUMATIC DISEASES CAUSING SIMILAR SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|---|

| Fevers | Systemic JIA, SLE, vasculitis, acute rheumatic fever, sarcoidosis, MCTD | Malignancies, infections and post-infectious syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease, periodic fever syndromes, Kawasaki disease, HSP |

| Arthralgias | JIA, SLE, rheumatic fever, JDM, scleroderma, sarcoidosis | Hypothyroidism, trauma, endocarditis, other infections, pain syndromes, growing pains, malignancies, overuse syndromes |

| Weakness | JDM, myositis secondary to SLE, MCTD, and deep localized scleroderma | Muscular dystrophies, metabolic and other myopathies, hypothyroidism |

| Chest pain | Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, SLE (with associated pericarditis or costochondritis) | Costochondritis (isolated), rib fracture, viral pericarditis, panic attack, hyperventilation |

| Back pain | Spondyloarthropathy, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis | Vertebral compression fracture, diskitis, intraspinal tumor, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, bone marrow–occupying malignancy, pain syndromes, osteomyelitis, muscle spasm, injury |

| Fatigue | SLE, JDM, MCTD, vasculitis, JIA | Pain syndromes, chronic infections, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression |

HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; JDM, juvenile dermatomyositis; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; MCTD, mixed connective tissue disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Arthralgia may also be a presenting symptom of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and chronic childhood arthritis such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Interestingly, many children with JIA do not complain of joint symptoms at presentation. Other symptoms more suggestive of arthritis include morning stiffness, joint swelling, limited range of motion, pain with joint motion, gait disturbance, fever, and fatigue and/or stiffness after physical inactivity (gelling phenomenon). A diagnosis of chronic juvenile arthritis cannot be made without the finding of arthritis on physical examination (Chapters 149 and 150), and there are no laboratory tests diagnostic of JRA or any other chronic inflammatory arthritis in childhood.

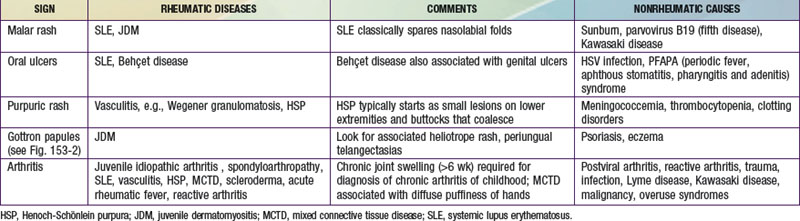

Signs Suggestive of Rheumatic Disease

Presence of a photosensitive malar rash that spares the nasiolabial folds is suggestive of SLE (Table 147-2; see Fig. 152-1A), especially in an adolescent girl. Diffuse facial rash is more indicative of JDM. A hyperkeratotic rash on the face or around the ears of an adolescent African-American girl may represent discoid lupus (see Fig. 152-1D). A palpable purpuric rash on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities points to Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP; see Fig. 161-1A). Less localized purpuric rashes and petechiae are present in systemic vasculitis or blood dyscrasias including coagulopathies. Nonblanching erythematous papules on the palms are seen in vasculitis and SLE. Gottron papules (see Fig. 153-2) and heliotrope rashes (see Fig. 153-1) along with erythematous rashes on the elbows and knees are pathognomonic of JDM. Dilated capillary loops in the nail beds (periungual telangectasias; see Fig. 153-3) are common in JDM, scleroderma, and secondary Raynaud phenomenon. An evanescent macular rash associated with fever is part of the diagnostic criteria for systemic onset arthritis (see Fig. 149-9). Sun sensitivity or photosensitive rashes are indicative of SLE or JDM but can also be caused by antibiotics.

Mouth ulcers are part of the diagnostic criteria for SLE and Behçet disease (see Fig. 152-1D); painless nasal ulcers and erythematous macules on the hard palate are also common in SLE. Cartilage loss in the nose, causing a saddle nose deformity, is classically present in Wegener granulomatosis (see Fig. 161-5) but is also seen in relapsing polychondritis and syphilis. Alopecia can be associated with SLE but is also found in localized scleroderma (see Fig. 154-4) and JDM. Raynaud phenomenon may be a primary benign idiopathic disorder or can be a presenting complaint in the child with scleroderma, lupus, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), or an overlap syndrome. Diffuse lymphadenopathy is present in many rheumatic diseases, including SLE, polyarticular JIA, and systemic JIA. Irregular pupils may represent the insidious and unrecognized onset of uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis. Erythematous conjunctiva may be a result of uveitis or episcleritis associated with JRA, SLE, sarcoidosis, spondyloarthropathies, or vasculitis.

Laboratory Testing

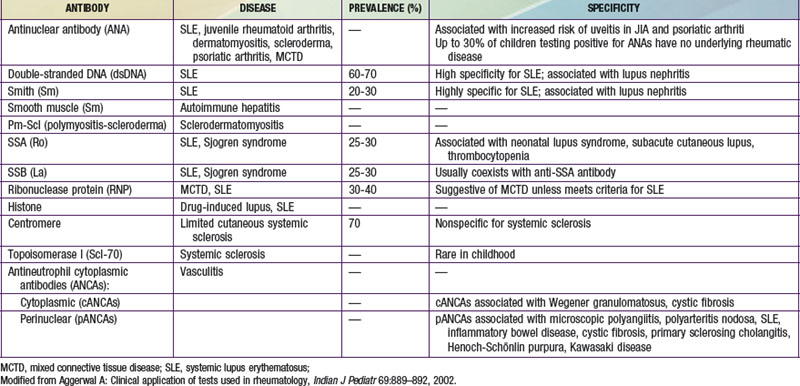

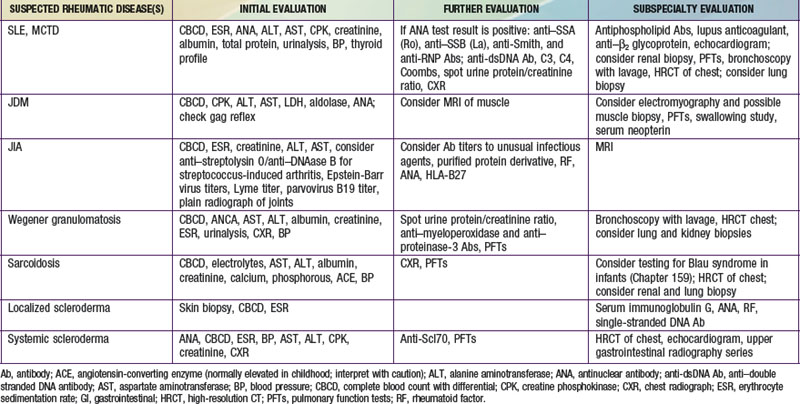

There are no specific screening tests for rheumatologic disease. Once a differential diagnosis is determined, appropriate testing can be performed (Tables 147-3 and 147-4). Initial studies are generally performed in standard local laboratories. Screening for specific autoantibodies can be performed in commercial laboratories, but confirmation of results in a tertiary care center immunology laboratory is often necessary.

The use of an antinuclear antibody (ANA) measurement as a screening test is not recommended, as it has low specificity. A positive ANA test result may be induced by infection, especially EBV infection, endocarditis, and parvovirus B19 infection. The ANA test result is also positive in up to 30% of normal children and the level of ANA is increased in those with a first-degree relative with a known rheumatic disease. In the majority of children with a positive ANA test result without signs of a rheumatic disease on initial evaluation autoimmune disease does not develop, so this finding does not necessitate referral to a pediatric rheumatologist. A positive ANA test result is found in many rheumatic diseases, including JIA, in which it serves as a predictor of the risk for inflammatory eye disease. Once a positive ANA test result is discovered in a child, the need for specific autoantibody testing is directed by the presence of clinical signs and symptoms (see Table 147-3).

Imaging Studies

Plain radiographs are useful in evaluation of arthralgias and arthritis, as they offer reassurance in benign pain syndromes and their findings are often abnormal in malignancies, osteomyelitis, and long-standing chronic juvenile arthritis. Radionucleotide bone scans help localize areas of abnormality in the patient with diffuse pains due to osteomyelitis, neuroblastoma, chronic multifocal osteomyelitis, and systemic arthritis. MRI findings are abnormal in inflammatory myositis and suggest the optimal site for biopsy. MRI is more sensitive than plain radiographs in detecting the presence of early erosive arthritis and demonstrates increased joint fluid, synovial enhancement, and sequela of trauma with internal joint derangement. Cardiopulmonary evaluation is suggested for diseases commonly affecting the heart and lung, including SLE, systemic scleroderma, MCTD, JDM, and sarcoid, as clinical manifestations may be subtle. This evaluation, which may include echocardiogram, pulmonary function tests, and high-resolution CT of the lungs along with consideration of bronchoalveolar lavage, is generally performed by a pediatric rheumatologist to whom the patient is referred (see Table 147-4).

Aggerwal A. Clinical application of tests used in rheumatology. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:889-892.

Arnalda C, Terreri MT, Puccini RF, et al. Development of a tool for early referral of children and adolescents with signs and symptoms suggestive of chronic arthropathy to pediatric rheumatology centers. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:373-377.

Breda L, Nozzi M, De Sanctis S, et al. Laboratory tests in the diagnosis and follow-up of pediatric rheumatic diseases: an update. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009. Feb 24 [epub ahead of print]

Foster HE, Kay LJ, Friswell M, et al. Musculoskeletal screening examination (pGALS) for school-age children based on the adult GALS screen. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:709-716.

Junnila JL, Cartwright VW. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: part I. Initial evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:115-122.

Junnila JL, Cartwright VW. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: part II. Rheumatic causes. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:293-300.

Jones OY, Spencer CH, Bowyer SL, et al. A multicenter case-control study on predictive factors distinguishing childhood leukemia from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e840-e844.

Keenan GF, Ostrov BE, Goldsmith DP, Athreya BH. Rheumatic symptoms associated with hypothyroidism in children. J Pediatr. 1993;123:586-588.

LaPlant MM, Adams BS, Haftel HM, et al. Insomnia and quality of life in children referred for limb pain. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2486-2490.

McGhee JL, Burks FN, Sheckels JL, et al. Identifying children with chronic arthritis based on chief complaints: absence of predictive value for musculoskeletal pain as an indicator of rheumatic disease in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:354-359.

McGhee JL, Kickingbird LM, Jarvis JN. Clinical utility of antinuclear antibody tests in children. BMC Pediatrics. 2004;4:13-18.