Chapter 32 Evaluation of Gastric Polyps and Thickened Gastric Folds

Introduction

Gastric polyps are detected in 3% of upper endoscopic evaluations,1 but the incidence is higher than in the past because of the increasing use of endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of upper digestive tract diseases.2 These polyps are usually asymptomatic and are often found incidentally on endoscopic or radiographic examination. They may occur sporadically or be associated with polyposis syndromes. Gastric polyps may be single or multiple in number and pedunculated or sessile in form. Depending on the type of polyp, variable sizes can be encountered ranging from millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Generally, gastric polyps are usually small (diameter <1 cm), well circumscribed, clearly demarcated, and project above the level of surrounding mucosa. Because of its diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic ability, endoscopy is the examination of choice in the diagnosis and treatment of gastric polyps.

Gastric polyps can be divided into epithelial and nonepithelial lesions. This chapter reviews the various types of epithelial gastric polyps and discusses the endoscopic techniques of gastric polypectomy, surveillance, and management. Nonepithelial gastric tumors including submucosal tumors are discussed in Chapter 29, and the management of upper gastrointestinal (GI) hereditary polyposis syndromes is discussed in Chapter 34. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the evaluation of thickened gastric folds, differential diagnoses, and endoscopic techniques and management.

Epithelial Gastric Polyps

Epithelial gastric polyps are divided into nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions. In contrast to colonic polyps, most gastric polyps are nonneoplastic (80%–90%), including fundic gland and hyperplastic polyps. Although hyperplastic polyps are not neoplastic, dysplasia or gastric adenocarcinoma, or both, may rarely develop within the lesion.3 Neoplastic epithelial gastric polyps include adenomas and polypoid gastric carcinomas.

Fundic Gland Polyps

Fundic gland polyps (also known as Elster’s glandular cysts and cystic hamartomatous epithelial polyps) constitute up to 77% of all gastric polyps and are observed in 3.2% of routine upper endoscopy procedures.4 They are more common in women and patients with Helicobacter pylori infection.5,6 The pathogenesis is unknown. These polyps usually occur sporadically but at increased frequency in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and patients receiving long-term proton pump inhibitor treatment.6,7 Although fundic gland polyps are traditionally considered a condition with little or no malignant potential, some reports have shown a possible increased association of concomitant colorectal adenomas or carcinomas in patients with fundic gland polyps.8,9 Dysplasia and adenomatous changes in fundic gland polyps have developed in 1% to 1.9% of sporadic cases10 and in 25% to 44% of patients with FAP.9,11 In addition, reports have suggested malignant transformation of fundic gland polyps in patients with FAP, which may occur more often than previously believed.11,12 Management of FAP syndrome is discussed in Chapter 34. The development of fundic gland polyps has also been associated with long-term proton pump inhibitor use,13–15 but some studies have shown that a causal pathogenetic relationship is unlikely.16,17

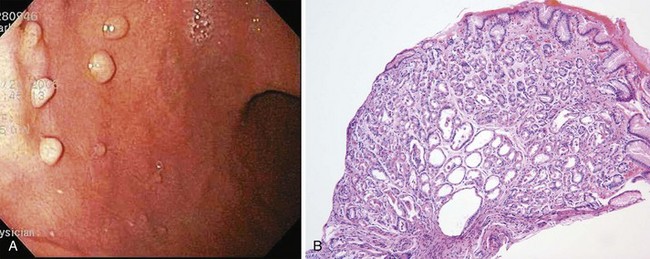

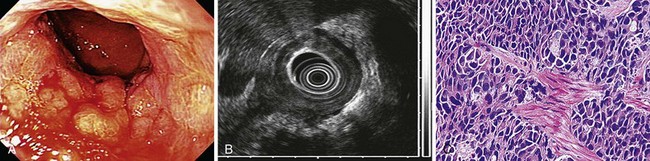

Histologically, fundic gland polyps are characterized by dilated glands forming microcysts lined with fundic-type parietal and chief cells. Endoscopically, fundic gland polyps are usually found in the fundus or body of the stomach (Fig. 32.1). They may be found as a solitary lesion, but are often multiple in closely packed clusters, resembling small round grapes. These lesions are generally 2 to 3 mm in diameter, and because of their small size, they are sometimes hidden between folds. The mucosal surface typically is the normal surrounding mucosal color but also can be pale in coloration; visualization is best when the stomach is fully distended.

Hyperplastic Polyps

Hyperplastic polyps are another common polypoid lesion in the stomach, constituting 73% of all gastric polyps in some series.18 The large variability in frequency is likely due to differing definitions of hyperplastic polyps. Men and women are equally affected, with predominance in adults older than 60 years. These polyps have previously been regarded as having no malignant potential; however, this is no longer thought to be true because of the increasing number of dysplastic changes or carcinoma found in gastric hyperplastic polyps.3,19,20 Focal carcinomas occurred in 2.1% of gastric hyperplastic polyps in one large Japanese series.21 In addition, within the same series, foci of dysplasia were seen in 4.0% of gastric hyperplastic polyps. The prevalence of true dysplasia arising from hyperplastic polyps is debated, with reported rates ranging from 1.9% to 19%.22 In contrast to gastric fundic gland polyps that tend to arise from otherwise normal gastric mucosa, hyperplastic polyps have been associated with chronic gastritis, particularly with autoimmune gastritis,22–24 and H. pylori gastritis.25 It has been shown more recently that H. pylori eradication leads to hyperplastic polyp disappearance26,27; this may provide an initial medical therapy before endoscopic removal.

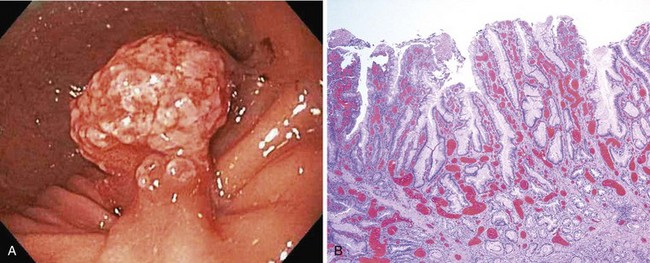

The histology of gastric hyperplastic polyps differs from that of hyperplastic colorectal polyps in that gastric ones have submucosal edema with prominent foveolar hyperplasia and inflammation of the lamina propria. Endoscopically, hyperplastic polyps can be found throughout the stomach and range in size from small nodules of a few millimeters to a large mass of many centimeters that may be mistaken for carcinoma. They can be solitary or multiple and may be sessile or pedunculated with an associated stalk. If multiple polyps are found, the prevalence of associated atrophic gastritis may be 20% to 30%, and the polyps usually are more proximal in location.22,28 The overlying mucosa may be normal in appearance, but the mucosa often has a reddish coloration in larger polyps (Fig. 32.2). Because of local trauma, larger hyperplastic polyps often have a friable, ulcerated whitish tip of granulation tissue and may be surrounded by atrophic or inflamed-appearing mucosa. There is no consensus regarding endoscopic removal and surveillance of hyperplastic gastric polyps. Details of management are discussed later.

Gastric Adenomatous Polyps

Adenomatous polyps of the stomach are less common than nonneoplastic epithelial lesions, constituting 7% to 10% of gastric polypoid lesions.29,30 Gastric adenomas are true neoplasms and are premalignant lesions with an increasing risk of developing into adenocarcinoma depending on the size and structure. Up to 24% of gastric adenomas may harbor a focus of adenocarcinoma, especially if greater than 2 cm in diameter.31 Malignancy can be found in lesions of any size, however. These lesions often arise in stomachs with a background of mucosal atrophy and are a marker for increased risk of adenocarcinoma elsewhere in the stomach.30,32 Gastric adenomas have been associated with FAP but not as frequently as fundic gland polyps.

Histologically, gastric adenomas are characterized by columnar epithelium that is pseudostratified and shows elongated atypical nuclei and increased mitotic activity; they can be divided into tubular, villous, and tubulovillous types. Dysplasia and carcinomatous changes occur most often in villous and tubulovillous adenomas (28.5% to 40%).33–36 Endoscopic evaluation of gastric adenomas should consist of a careful complete examination of the surrounding mucosa and biopsy of any suspicious lesion. These lesions can be found in any location of the stomach but seem to have a predilection for the antrum.37 Gastric adenomas are generally larger than hyperplastic polyps, usually around 3 to 4 cm in diameter, but can also range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. The mucosal surface is usually smooth with a reddish coloration and often with a cerebriform mucosal pattern. The shape of gastric adenomas can vary, ranging from single, round, sessile projections to multilobulated lesions. Villous-type lesions are sometimes difficult to detect because of the flat, sessile, carpetlike appearance that can blend in with the surrounding rugae. Rarely, flat or depressed adenomas are encountered.38

Because of their malignant potential, the consensus is that all gastric adenomatous polyps need to be completely removed either endoscopically or by laparoscopic wedge resection. In addition, a thorough biopsy of the surrounding gastric mucosa should be performed. The recurrence rate of adenomatous polyps may be 16% after polypectomy.39 Endoscopic techniques and management are discussed in more detail later.

Polypoid Gastric Carcinoma

Because of similar appearance, endoscopic determination of adenomatous gastric polyps versus genuine malignant lesions is extremely difficult without histologic confirmation. Synchronous or metachronous gastric cancers have been found in 11% of patients with adenomas.34 Gastric adenocarcinomas may develop as polypoid lesions (Borrmann type A) and are differentiated into type I (protruded, polypoid type) and type IIa (superficial elevated type).40

Subepithelial Gastric Polyps

Subepithelial gastric polyps consist of a heterogeneous group of lesions that are usually small and difficult to differentiate between hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps. These nonepithelial lesions are usually covered by normal-appearing mucosa and have various causes, including carcinoid tumors, lipomas, aberrant pancreas (pancreatic rest, heterotopic pancreas), inflammatory fibroid polyps, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (including leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, schwannomas, fibromas, and others). Chapter 29 contains a complete discussion of nonepithelial tumors of the stomach.

Endoscopic Techniques and Management

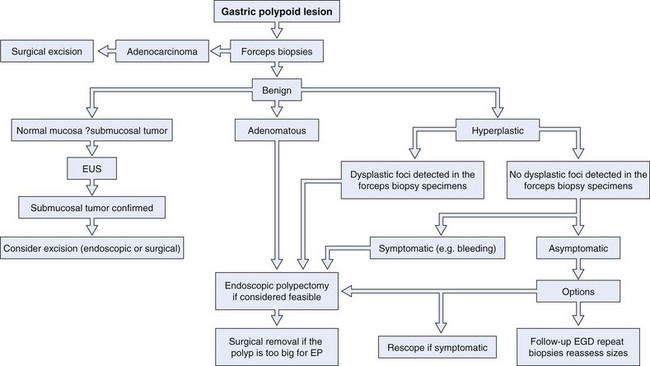

Gastric polyps are rarely symptomatic and often discovered incidentally. The first step in the management of a gastric polyp is to identify the tissue histology (Fig. 32.3). Because the histology of a gastric polyp cannot be reliably distinguished using a standard endoscope, biopsy or excision of gastric polypoid lesions found on upper endoscopy should be performed. This recommendation may change, however, as more studies using magnification or zoom endoscopy identify mucosal patterns that correlate with histology.41,42 Although forceps biopsy is a simple method of obtaining tissue, it may provide inadequate tissue or sampling error. Studies have shown inconsistencies between histologic diagnosis made by forceps biopsy and a subsequent snare polypectomy specimen.43,44 Muehldorfer and coworkers45 conducted a prospective multicenter study comparing the diagnostic accuracy of forceps biopsy versus polypectomy in 222 gastric polyps greater than 5 mm (excluded fundic gland polyps). Relevant differences were found in 2.7% of cases in which there was failure to reveal foci of carcinoma on forceps biopsy in a group of hyperplastic polyps. Similarly, a study from Hungary showed significant disagreements in 27% of cases.43 Endoscopic removal of all epithelial gastric polyps larger than 5 mm is encouraged by these authors.

Fig. 32.3 Evaluation and management of a gastric polypoid lesion.

(Adapted from Lau CF, Hui PK, Mak KL, et al: Gastric polypoid lesions—illustrative cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol 93:2559–2564, 1998.)

If multiple gastric polyps are found, additional risk is presented to the patient if multiple snare excisions are performed. Although complete excision is preferred, this may not be technically feasible or practical; the risks and benefits should be individualized for each patient. In this scenario, resection could be delayed until forceps biopsy results are reviewed. Although gastric polyps that are multiple in number are usually of the same histologic type,46 hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps can be found together.35,39 One strategy to use when addressing multiple gastric polyps is to remove the larger polyps when feasible and safe by snare excision and perform multiple forceps biopsies of the smaller polyps. It is hoped that this approach would give a complete representation of the histology of the lesions encountered, while minimizing risk of a missed neoplasm. If one or more foci of dysplasia are detected in a biopsy specimen from a gastric hyperplastic polyp, the polyp should be removed, even if it is not symptomatic.

Controversy exists regarding the management of incidentally found gastric hyperplastic polyps with no focus of dysplasia on biopsy. Some authors recommend endoscopic removal of all hyperplastic polyps encountered because of the small risk of missing an area of dysplasia within the forceps biopsy.34,43,44,47 Others propose endoscopically removing small polyps and periodic biopsy of hyperplastic polyps that are too large for safe complete polypectomy,48 depending on the level of endoscopic expertise.

There is no consensus at the present time on the most appropriate frequency and duration of endoscopic follow-up of hyperplastic polyps.49 Until well-designed, long-term prospective studies are available on the management of gastric polyps, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has developed general recommendations, as follows50:

Endoscopic Techniques and Considerations

Gastric polypectomy, similar to all invasive procedures, carries a potential for injury to the patient. The patient should be aware of the added risks of possible complications before giving informed consent, especially if the diagnosis of gastric polyps is already known. Pedunculated polyps with thin stalks can be safely removed by snare cautery. For larger polyps on a thick pedicle, there is concern of a “feeder vessel” within the stalk. For pedunculated polyps greater than 1 cm in diameter, endoscopic resection can be assisted by using a grasping forceps through a snare technique, as described by Akahoshi and colleagues.51 In this technique, using a dual channel endoscope, grasping forceps are inserted in one channel through the detachable snare loop previously inserted in the second channel. The detachable snare loop (Endoloop; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) can provide extra hemostasis to reduce the risk of bleeding after polypectomy. Endoscopic resection using a detachable loop is a useful method of preventing polypectomy-related bleeding.52

Large gastric polyps that are sessile can be removed in piecemeal fashion, but if a transmural lesion is suspected, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and high-frequency miniprobes53 can be useful in determining the depth of invasion. Early cancer polypoid lesions can be successfully removed with the use of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection.54 With the assistance of ultrasound, EMR is safe and effective for the management of selected submucosal lesions.53 The approach to submucosal tumors and techniques of EMR are discussed in more detail in Chapter 29.

The incidence of hemorrhage from gastric polypectomy is about 7%.55 For hemostasis, 2 to 4 mL of 1 : 10,000 epinephrine solution diluted with saline can be injected into the stalk before or after resection. Additional hemostasis can be provided by endoscopically deployed metallic clips (Hemoclip; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) to provide mechanical compression to the target tissue. A retrospective study showed that the prophylactic use of hemoclips is associated with a low risk of bleeding (3.3%) after polypectomy of polyps 15 to 40 mm in diameter.56 In addition, thermal hemostatic devices such as bipolar electrocautery or heater probe (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) can deliver thermal energy to give additional hemostasis.

Resected polyps should be recovered and sent for pathologic examination, which is essential when the diagnosis is uncertain. Devices designed for polyp retrieval include grasping forceps, nets, baskets, and plastic traps.57 The Roth retrieval net (United States Endoscopy Group, Inc., Mentor, OH) is a single-use device that comprises a net over a retractable loop that captures the polyp after polypectomy.

Thickened Folds

Thickened folds often present a diagnostic challenge to the endoscopist, particularly in the stomach. Standard endoscopic biopsies are often unrevealing and often contain only superficial mucosa despite tunneled deep biopsy specimens. Although obtaining specimens from deeper layers with a diathermic snare can increase the diagnostic yield, there is increased risk of hemorrhage or perforation.58,59 In addition, the etiologies of thickened gastric folds are extremely varied, and thickened gastric folds are a common feature in both benign and malignant diseases. The more common and classic etiologies are discussed individually.

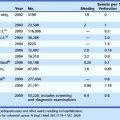

With the introduction of EUS, individual gut wall layers and accurate measurement of wall thickness is possible. Both high-frequency ultrasound probe sonography and dedicated echoendoscopes are useful for evaluation.60,61 The gastric wall is considered thickened if greater than 3.6 mm and especially if greater than 4.0 mm. In normal gastric folds, there are five wall layers of the GI tract that are roughly proportional in size. The five EUS layers are: layer 1, the interface between the transducer or the fluid surrounding the transducer and the mucosa; layer 2, the deep mucosa and the muscularis mucosae; layer 3, the submucosa; layer 4, the muscularis propria; and layer 5, the serosa/adventitia. Different diseases show different levels of infiltration with regional thickening of distinct layers, which can refine potential diagnoses by EUS. Specific causes of thickened folds and their EUS features are listed in Table 32.1.

Table 32.1 Diseases Considered in Evaluation with Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) of Thickened Folds and Layers Principally Involved

| Etiology of Thickened Folds | EUS Wall Layer Involved |

|---|---|

| Gastric varices | 2 and 3 |

| Gastritis | 2 and 3 |

| Carcinoma and lymphoma | 2–5 |

| Hypertrophic gastric folds | 2 and 3 |

| Zollinger-Ellison syndrome | 2 and 3 |

| Ménétrier’s disease | 2 and 3 |

| Gastritis cystica profunda | 3 |

| Hyperrugosity | 2 and 3 |

| Rectal ulcer and prolapse syndromes | 2, 3, and 4 |

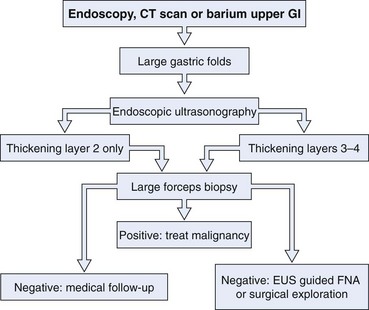

The initial EUS approach to thickened gastric folds should be to evaluate the layer thickness. When EUS abnormalities involve only the mucosal layer or layer 2, endoscopic biopsies are usually diagnostic.62 If layers 2 and 3 are involved, deep or large forceps biopsies should be considered. Malignancy should be strongly suspected if layer 4 is involved or the muscularis propria is thickened, even if normal biopsy specimens are obtained.62–64 Finally, many experts instill water into the lumen to improve image quality during EUS, although risk of aspiration should be carefully considered. An algorithm for the evaluation of thickened gastric folds is presented in Fig. 32.4.

Gastric Varices

Gastric varices are seen in the submucosal layer as distinct hypoechoic structures by EUS and are often described as wormlike. The mucosal and submucosal layers (layers 2 and 3) may be thickened in portal hypertension. Engorgement of larger vessels, such as the splenic and portal veins, perigastric collateral veins, and gastric perforating veins, may also be seen.65 If gastric varices are identified or suspected, biopsies should not be done. Thickened gastric folds in the cardia or fundus should be evaluated by EUS if indicated.66 The use of color Doppler EUS can verify blood flow and calculate blood flow volume and velocity, which can be monitored during therapy.67 In addition, EUS has been used for local treatment with cyanoacrylate injection.68

Gastritis

Another cause of superficial wall layer thickening is gastritis, which involves the mucosa and submucosa (layers 2 and 3). Infectious etiologies are common, especially H. pylori.69,70 Resolution of H. pylori gastritis–induced gastric fold thickening occurs after eradication of the organism.70 Inflammatory conditions have also been implicated, particularly conditions resulting in granuloma formation such as sarcoidosis71 and Crohn’s disease.72,73 Hirokawa and colleagues73 described a “bamboo joint–like” endoscopic appearance characterized by swollen longitudinal folds traversed by erosive fissures in the stomach of 15 of 23 patients who had Crohn’s disease. Mucosal nodularity or cobblestone mucosa with thickening of the antral folds in patients with Crohn’s disease has also been described.72 When infection or the inflammatory reaction is severe, involvement can sometimes include deeper wall layers as well, raising concern for malignancy.74

Ménétrier’s Disease (Giant Hypertrophic Gastritis)

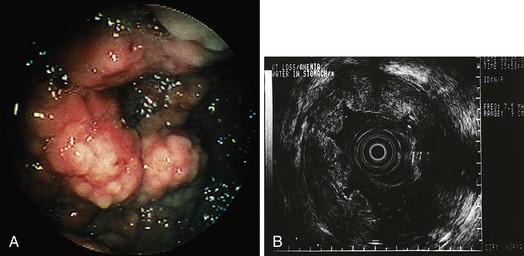

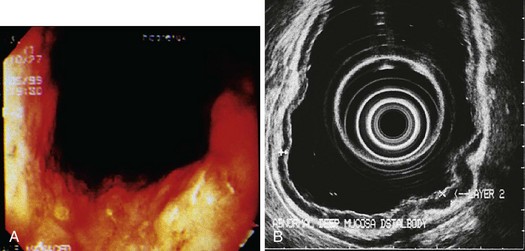

Ménétrier’s disease is a rare condition whose origin seems to be related to an overexpression of transforming growth factor-α in the surface mucous cells in the body and fundus of the stomach.75 It involves marked thickening of EUS layers 2 and 3 with histologic features of foveolar hyperplasia and atrophy of glands (Fig. 32.5). Erosions or ulceration may be present on the enlarged folds and may appear convoluted or cerebriform with a reddish coloration. These patients usually present with weight loss, diarrhea, and edema. Ménétrier’s disease is characterized by (1) giant folds, especially in the fundus and body of the stomach; (2) hypoalbuminemia; and (3) histologic features of foveolar hyperplasia, atrophy of glands, and a marked overall increase in mucosal thickness. EUS differentiation of Ménétrier’s disease and lymphoma may be difficult because both display similar echo patterns. Pinch biopsies are usually insufficient for diagnosis, whereas loop biopsy using a polypectomy snare over a fold yields better results for diagnosis. Submucosal saline injection technique can also be applied to help raise the lesion before removal.

Lymphoma and Carcinoma

Malignancy should always be considered when evaluating thickened gastric folds. As mentioned previously, involvement of the muscularis propria (EUS layer 4) should prompt concern for malignancy and consideration of surgical biopsy, even if aggressive endoscopic biopsy techniques are performed and return unremarkable. In these situations, the muscularis propria layer can be thickened fourfold to sixfold compared with controls.64,76 Both lymphoma and carcinoma involve the deeper wall layers exclusively, without mucosal disease,63 so this diagnosis could easily be missed on standard endoscopy. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) or a surgical approach should be attempted for obtaining tissue diagnosis. Diffuse gastric cancers (linitis plastica, scirrhous carcinoma) are seen as diffuse hypoechoic wall thickening covered by normal-appearing mucosa but often with distorted layers and an irregular-appearing outer margin on EUS (Fig. 32.6). In contrast, in patients with hypertrophic gastritis only the mucosal layer is thickened.76

Lymphoma more often involves the superficial layers as well, particularly in mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. The role of EUS in MALT lymphoma has received considerable attention, primarily because EUS can predict disease that may respond to H. pylori eradication as the sole means of therapy.77 Complete remission rates of 100% have been described for patients with T1 stage low-grade MALT lymphoma (Fig. 32.7).78 In addition, EUS surveillance helps detect persistent disease, recurrences, and the need for aggressive chemotherapy.79 Miniature ultrasound probes have been advocated for initial staging and follow-up of MALT lymphoma because of better resolution of superficial lesions.80,81

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Gastrinoma, or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), is a rare condition that can be associated with thick gastric folds. It is estimated to occur in 0.1 to 3 patients per 1 million of the U.S. population, with a mean age of diagnosis of 50 years.82 ZES should be suspected in patients with severe erosive esophagitis, multiple or refractory peptic ulcers, and ulcers in unusual locations and in patients with a family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I and related gastrinomas.83 Ulcers in ZES are usually less than 1 cm in diameter, and approximately 75% of ulcers are located in the first portion of the duodenum. Histologically, ZES is characterized as hyperproliferation of enterochromaffinlike and parietal cells with glandular hyperplasia resulting from trophic effects of gastrin produced by a gastrinoma. EUS evaluation of thickened folds shows thickening of layers 2 and 3 in the body and fundus. EUS accuracy for gastrinomas is around 80%.84 Tumor localization is done by somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, EUS, or both.

Miscellaneous

There are several rare miscellaneous causes of thickened gastric folds. Metastatic disease, particularly from breast cancer, may manifest as thickening and disruption of the wall layers.85 Gastritis cystica profunda involves EUS layer 3 and appears as multiple small cysts, which are histologically benign. Malignant infiltration may also result in cystic changes in EUS layers 2 and 3; diagnosis must be based on adequate histologic analysis such as EMR specimens.86

1 Dekker W. Clinical relevance of gastric and duodenal polyps. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990;178:7-12.

2 Sivelli R, Del Rio P, Bonati L, et al. [Gastric polyps: A clinical contribution]. Chir Ital. 2002;54:37-40.

3 Hattori T. Morphological range of hyperplastic polyps and carcinomas arising in hyperplastic polyps of the stomach. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38:622-630.

4 Carmack SW, Genta RM, Schuler CM, et al. The current spectrum of gastric polyps: A 1-year national study of over 120,000 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1524-1532.

5 Genta RM, Schuler CM, Robiou CR, et al. No association between gastric fundic gland polyps and gastrointestinal neoplasia in a study of over 100,000 patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:849-854.

6 Samarasam I, Roberts-Thomson J, Brockwell D. Gastric fundic gland polyps: A clinico-pathological study from North West Tasmania. Aust N Z J Surg. 2009;79:467-470.

7 Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, et al. Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1341-1348.

8 Jung A, Vieth M, Maier O, et al. Fundic gland polyps (Elster’s cysts) of the gastric mucosa. A marker for colorectal epithelial neoplasia? Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:731-734.

9 Eidt S, Stolte M. Gastric glandular cysts—investigations into their genesis and relationship to colorectal epithelial tumors. Z Gastroenterol. 1989;27:212-217.

10 Kinoshita Y, Tojo M, Yano T, et al. Incidence of fundic gland polyps in patients without familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:161-163.

11 Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Nigrisoli E, et al. Dysplastic changes in gastric fundic gland polyps of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31:192-197.

12 Hofgartner WT, Thorp M, Ramus MW, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma associated with fundic gland polyps in a patient with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2275-2281.

13 Stolte M, Bethke B, Seifert E, et al. Observation of gastric glandular cysts in the corpus mucosa of the stomach under omeprazole treatment. Z Gastroenterol. 1995;33:146-149.

14 el-Zimaity HM, Jackson FW, Graham DY. Fundic gland polyps developing during omeprazole therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1858-1860.

15 Choudhry U, Boyce HWJr, Coppola D. Proton pump inhibitor-associated gastric polyps: A retrospective analysis of their frequency, and endoscopic, histologic, and ultrastructural characteristics. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:615-621.

16 Oberhuber G, Stolte M. Gastric polyps: An update of their pathology and biological significance. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:581-590.

17 Vieth M, Stolte M. Fundic gland polyps are not induced by proton pump inhibitor therapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:716-720.

18 Morais DJ, Yamanaka A, Zeitune JM, et al. Gastric polyps: A retrospective analysis of 26,000 digestive endoscopies. Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:14-17.

19 Rosen S, Hoak D. Intramucosal carcinoma developing in a hyperplastic gastric polyp. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:830-833.

20 Zea-Iriarte WL, Itsuno M, Makiyama K, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma in hyperplastic polyp. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:604-608.

21 Daibo M, Itabashi M, Hirota T. Malignant transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1016-1025.

22 Abraham SC, Singh VK, Yardley JH, et al. Hyperplastic polyps of the stomach: Associations with histologic patterns of gastritis and gastric atrophy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:500-507.

23 Krasinskas AM, Abraham SC, Metz DC, et al. Oxyntic mucosa pseudopolyps: A presentation of atrophic autoimmune gastritis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:236-241.

24 Laxen F. Gastric carcinoma and pernicious anaemia in long-term endoscopic follow-up of subjects with gastric polyps. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;19:535-540.

25 Veereman Wauters G, Ferrell L, Ostroff JW, et al. Hyperplastic gastric polyps associated with persistent Helicobacter pylori infection and active gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1395-1397.

26 Ji F, Wang ZW, Ning JW, et al. Effect of drug treatment on hyperplastic gastric polyps infected with Helicobacter pylori: A randomized, controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1770-1773.

27 Nakajima A, Matsuhashi N, Yazaki Y, et al. Details of hyperplastic polyps of the stomach shrinking after anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:372-375.

28 Tytgat GNJ, Lightdale CJ. Gastroenterological endoscopy. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2002.

29 Papa A, Cammarota G, Tursi A, et al. Histologic types and surveillance of gastric polyps: A seven year clinico-pathological study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:579-582.

30 Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, et al. Gastric adenomas: Intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1276-1285.

31 Kolodziejczyk P, Yao T, Oya M, et al. Long-term follow-up study of patients with gastric adenomas with malignant transformation: An immunohistochemical and histochemical analysis. Cancer. 1994;74:2896-2907.

32 Harju E. Gastric polyposis and malignancy. Br J Surg. 1986;73:532-533.

33 Nakamura T, Nakano G. Histopathological classification and malignant change in gastric polyps. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38:754-764.

34 Stolte M. Clinical consequences of the endoscopic diagnosis of gastric polyps. Endoscopy. 1995;27:32-37.

35 Tomasulo J. Gastric polyps: Histologic types and their relationship to gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1971;27:1346-1355.

36 Schmitz JM, Stolte M. Gastric polyps as precancerous lesions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:29-46.

37 Pisano R, Llorens P, Backhouse C, et al. [Anatomopathological study of 86 gastric adenomas: Experience in 14 years]. Rev Med Chil. 1996;124:204-208.

38 Nakamura K, Sakaguchi H, Enjoji M. Depressed adenoma of the stomach. Cancer. 1988;62:2197-2202.

39 Seifert E, Gail K, Weismuller J. Gastric polypectomy: Long-term results (survey of 23 centres in Germany). Endoscopy. 1983;15:8-11.

40 Borrmann R. Handbuch der Speziellen Pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie. Berlin: Springer; 1926.

41 Guelrud M, Herrera I, Essenfeld H, et al. Enhanced magnification endoscopy: A new technique to identify specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:559-565.

42 Yao K, Oishi T, Matsui T, et al. Novel magnified endoscopic findings of microvascular architecture in intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:279-284.

43 Szaloki T, Toth V, Tiszlavicz L, et al. Flat gastric polyps: Results of forceps biopsy, endoscopic mucosal resection, and long-term follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1105-1109.

44 Ginsberg GG, Al-Kawas FH, Fleischer DE, et al. Gastric polyps: Relationship of size and histology to cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:714-717.

45 Muehldorfer SM, Stolte M, Martus P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of forceps biopsy versus polypectomy for gastric polyps: A prospective multicentre study. Gut. 2002;50:465-470.

46 Deppisch LM, Rona VT. Gastric epithelial polyps: A 10-year study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:110-115.

47 Batovsky M, Vavrecka A, Pauer M, et al. Endoscopic gastroduodenal polypectomy. Czech Med. 1988;11:157-167.

48 De Salvo L, Ansaldo GL, Romairone E, et al. [Gastric polyps: Role of endoscopy]. Ann Ital Chir. 1990;61:153-156.

49 Lau CF, Hui PK, Mak KL, et al. Gastric polypoid lesions—illustrative cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2559-2564.

50 Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:570-580.

51 Akahoshi K, Kojima H, Fujimaru T, et al. Grasping forceps assisted endoscopic resection of large pedunculated GI polypoid lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:95-98.

52 Dell’Abate P, Del Rio P, Soliani P, et al. [Endoscopic polypectomy with the use of endoloop in giant gastric polyp: A case report]. Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. 2001;72:105-108.

53 Waxman I, Saitoh Y, Raju GS, et al. High-frequency probe EUS-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection: A therapeutic strategy for submucosal tumors of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:44-49.

54 Kojima T, Parra-Blanco A, Takahashi H, et al. Outcome of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: Review of the Japanese literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:550-554.

55 Bardan E, Maor Y, Carter D, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) before gastric polyp resection: Is it mandatory? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:371-374.

56 Sobrino-Faya M, Martinez S, Gomez Balado M, et al. Clips for the prevention and treatment of postpolypectomy bleeding (hemoclips in polypectomy). Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2002;94:457-462.

57 Ye F, Feng Y, Lin J. Retrieval of colorectal polyps following snare polypectomy: Experience of the multiple-suction technique in 602 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:431-436.

58 Bjork JT, Geenen JE, Soergel KH, et al. Endoscopic evaluation of large gastric folds: A comparison of biopsy techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;24:22-23.

59 Komorowski RA, Caya JG, Geenen JE. The morphologic spectrum of large gastric folds: Utility of the snare biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:190-192.

60 Buscarini E, Stasi MD, Rossi S, et al. Endosonographic diagnosis of submucosal upper gastrointestinal tract lesions and large fold gastropathies by catheter ultrasound probe. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:184-191.

61 Lugering N, Menzel J, Kucharzik T, et al. Impact of miniprobes compared to conventional endosonography in the staging of low-grade gastric malt lymphoma. Endoscopy. 2001;33:832-837.

62 Mendis RE, Gerdes H, Lightdale CJ, et al. Large gastric folds: A diagnostic approach using endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:437-441.

63 Chen TK, Wu CH, Lee CL, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis of giant gastric folds. J Formos Med Assoc. 1999;98:261-264.

64 Songur Y, Okai T, Watanabe H, et al. Endosonographic evaluation of giant gastric folds. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:468-474.

65 El-Saadany M, Jalil S, Irisawa A, et al. EUS for portal hypertension: A comprehensive and critical appraisal of clinical and experimental indications. Endoscopy. 2008;40:690-696.

66 Wong RC, Farooq FT, Chak A. Endoscopic Doppler US probe for the diagnosis of gastric varices (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:491-496.

67 Sung JJ, Lee YT, Leong RW. EUS in portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S35-S43.

68 Romero-Castro R, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Jimenez-Saenz M, et al. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate in perforating feeding veins in gastric varices: Results in 5 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:402-407.

69 Caletti G, Fusaroli P, Bocus P. Endoscopic ultrasonography in large gastric folds. Endoscopy. 1998;30(Suppl 1):A72-A75.

70 Avunduk C, Navab F, Hampf F, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with large gastric folds: Evaluation and follow-up with endoscopic ultrasound before and after antimicrobial therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1969-1973.

71 Marcato N, Abergel A, Froment S, et al. [Sarcoidosis gastropathy: Diagnosis and contribution of echo-endoscopy]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:394-397.

72 Danzi JT, Farmer RG, Sullivan BHJr, et al. Endoscopic features of gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:9-13.

73 Hirokawa M, Shimizu M, Terayama K, et al. Bamboo-joint-like appearance of the stomach: A histopathological study. APMIS. 1999;107:951-956.

74 Lagasse JP, Causse X, Legoux JL, et al. Cytomegalovirus gastritis simulating cancer of the linitis plastica type on endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S101-S102.

75 Coffey RJ, Washington MK, Corless CL, et al. Menetrier disease and gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Hyperproliferative disorders of the stomach. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:70-80.

76 Fujishima H, Misawa T, Chijiwa Y, et al. Scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach versus hypertrophic gastritis: Findings at endoscopic US. Radiology. 1991;181:197-200.

77 El-Zahabi LM, Jamali FR, El HajjII, et al. The value of EUS in predicting the response of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma to Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:89-96.

78 Sackmann M, Morgner A, Rudolph B, et al. Regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori is predicted by endosonographic staging. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1087-1090.

79 Caletti G, Fusaroli P, Togliani T. EUS in MALT lymphoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S21-S26.

80 Waxman I. Clinical impact of high-frequency ultrasound probe sonography during diagnostic endoscopy—a prospective study. Endoscopy. 1998;30(Suppl 1):A166-A168.

81 Yanai H, Yoshida T, Harada T, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography of superficial esophageal cancers using a thin ultrasound probe system equipped with switchable radial and linear scanning modes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:578-582.

82 Hirschowitz BI. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:44S-48S.

83 Hung PD, Schubert ML, Mihas AA. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2003;6:163-170.

84 Varas Lorenzo MJ, Miquel Collell JM, Maluenda Colomer MD, et al. Preoperative detection of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors using endoscopic ultrasonography. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2006;98:828-836.

85 Lorimier G, Binelli C, Burtin P, et al. Metastatic gastric cancer arising from breast carcinoma: Endoscopic ultrasonographic aspects. Endoscopy. 1998;30:800-804.

86 Hizawa K, Suekane H, Kawasaki M, et al. Diffuse cystic malformation and neoplasia-associated cystic formation in the stomach: Endosonographic features and diagnosis of tumor depth. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:634-639.