chapter 9 Evaluating the Respiratory System

Obtaining the History

Parents must understand your terminology, and you must understand theirs (see Chapter 1). What parents describe as a wheeze may, in fact, be stridor. What you call asthma may mean something much more alarming to parents. Do not assume that parents understand what is meant by terms such as wheeze. Be prepared to imitate a wheeze, stridor, or whoop, or ask the parents to imitate the sound they are trying to describe.

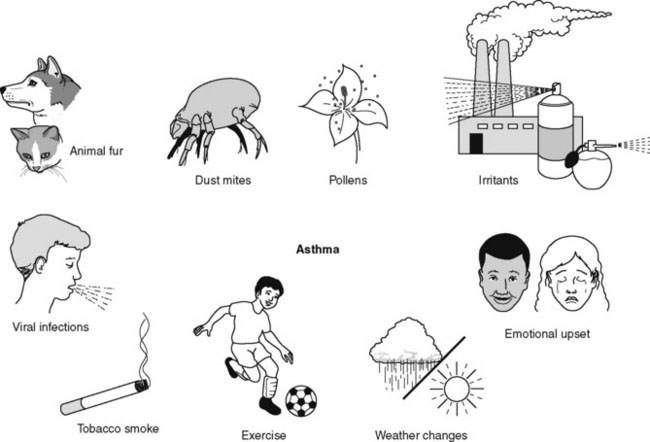

Some parents have difficulty recalling the circumstances or triggers that cause or aggravate their child’s respiratory symptoms. This situation occurs frequently in children with asthma. Have a prepared list of common asthma triggers on hand to help them (Fig. 9–1).

Chief complaints

Allergic rhinitis

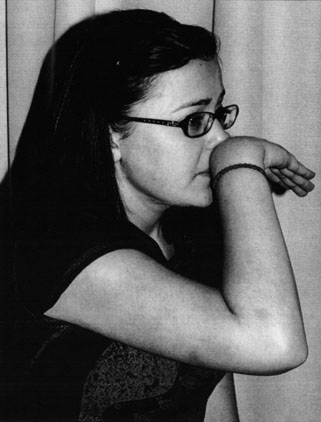

Because many parents are unfamiliar with the terms allergic rhinitis and hay fever, ask instead about whether the child has an itchy nose, a runny nose, displays the classic “allergic salute” (i.e., repeatedly rubbing the tip of the itchy nose with the palm or back of the hand) (Fig. 9–2), or has fits of sneezing. Establish whether any of these symptoms occur seasonally or year-round. Elicit the specific factors triggering these symptoms and the treatments that have been tried.

Approach to the Physical Examination

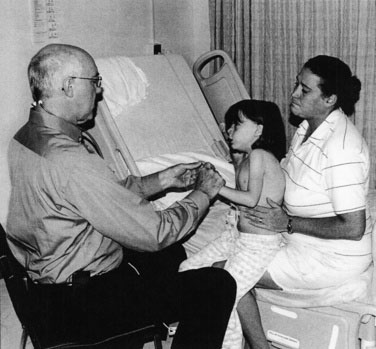

A complete examination of the respiratory system of an infant or young child often is best accomplished with the child sitting in the parent’s lap (Fig. 9–3). Having older children and teenagers sit on an examining table is best. Although the order in which the examination is performed is not crucial, it should be complete. Forgetting to examine the child for clubbing or to listen to the child’s cough are major omissions. Use a pediatric stethoscope when examining infants, because the diaphragm and bell of an adult stethoscope often are too large to be used with infants.

TABLE 9–1 Normal Respiratory Rates in Children Who are Awake

| Age (years) | Respiratory Rate (breaths/min) |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | 25–40 |

| 1–5 | 20–30 |

| 5–10 | 15–25 |

| 10–16 | 15–20 |

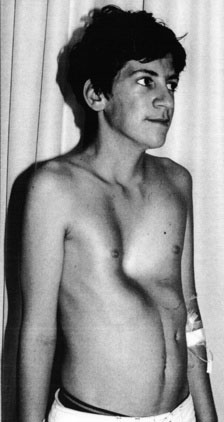

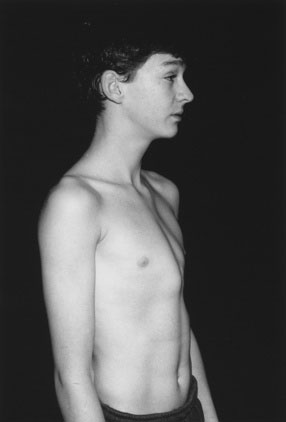

Chest wall shape and deformity

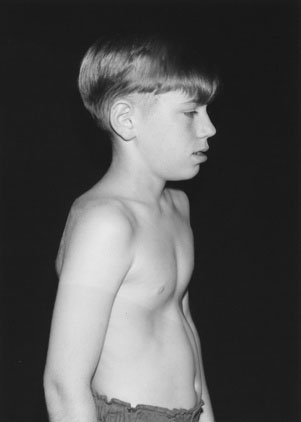

Observe whether the chest configuration is abnormal (Figs. 9-4 to 9-6); remember that infants’ chests are rounder than those of older children because of the more horizontal position of the ribs. Chronic, diffuse, small airway obstruction with air trapping produces an abnormally rounded or “barrel-shaped” chest with a greater anteroposterior diameter (see Fig. 9–4). This finding often is associated with subcostal or lower costal indrawing. Note bony thoracic deformities, such as pectus excavatum (funnel chest) (see Fig. 9–5) or pectus carinatum (pigeon breast) (see Fig. 9–6). As an isolated finding, pectus excavatum seldom is associated with any respiratory abnormalities. In some cases, pectus carinatum may be an isolated finding, but in other cases, it may signal a chronic cardiorespiratory problem. Occasionally, other chest wall deformities are found, which are either congenital or a result of thoracic surgery.

Kyphoscoliosis

Look at the spine’s configuration. Marked scoliosis affects the shape of the thoracic cage and may impede pulmonary function (Fig. 9–7).

Respiratory rate

An abnormally fast or slow respiratory rate may reflect a disturbance in the respiratory or cardiovascular system or in the central nervous system (CNS) control of breathing. Measure the respiratory rate by counting for a full minute. (See Table 9–1 for normal values at different ages.)

Finger clubbing

Inspect the lateral aspect of the finger and the angle formed at the skin-nail junction on the dorsal surface of the terminal phalanx. Finger clubbing (Fig. 9–8) results from a proliferation of nail bed tissue that raises the nail’s base. Gross clubbing is obvious, but subtle degrees of clubbing are easily missed. Clubbing is seen in children with CF, but it also can occur in children with other respiratory, cardiac, and gastrointestinal disorders.

Cough

Table 9–2 lists some common and some not so common respiratory illnesses and the types of cough associated with them.

| Illnesses | Cough | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bronchitis | Initially dry; after a few days, may become loose and rattling | Produces a small amount of sputum that is usually swallowed; occasionally, the sputum is thick and yellow, but this finding does not always indicate secondary infection |

| Asthma | Classic cough is dry, “tight,” and occasionally wheezy | Some children produce abundant secretions with a wet cough; coughing may be spasmodic, occur mainly at night, and be associated with vomiting; throat clearing that parents believe to be a habit may be an early manifestation of asthma; a wet asthma cough can mimic a cystic fibrosis cough |

| Croup (acute laryngotracheo-bronchitis) | Sounds like the “bark” of a seal | Sudden onset; the child goes to bed well or with a slight cold; often associated with an inspiratory stridor and a hoarse voice |

| Pertussis | Spasmodic, choking, repetitive cough with no inspiration during coughing spasms | Associated with eye tearing, profuse secretions, and facial suffusion; spasm punctuated by sudden crowing inspiration (the “whoop”) or vomiting |

| Pulmonary inhalation | May be dry or loose; often associated with lower airway obstructions | More commonly heard in children with swallowing incoordination or developmental delay; can be similar to the cough of asthma, bronchitis, or bronchiolitis |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae pneumonia | Typically paroxysmal, dry, and staccato (with a short inspiration between coughs), unlike pertussis | Usually occurs in young infants |

| Tracheomalacia | Has loud characteristic brassy or vibratory sound, reflecting its tracheal origin | When associated with coarse inspiratory and expiratory stridor, or an inspiratory stridor and an expiratory wheeze, the cough virtually pinpoints the diagnosis |

| Psychogenic | Uncommon, but not rare, cough; sounds like the loud “honk” of a Canada goose | Remarkably, this cough never occurs during sleep |

Noisy breathing

Pay careful attention to any sounds emitted by the child while he or she breathes. See Table 9–3 for a full description of these sounds.

| Noise | Quality | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Snoring | Inspiratory noise of irregular quality | Produced by partial obstruction of the upper respiratory tract, usually in the region of the naso-oropharynx |

| Stridor | Continuous, usually harsh inspiratory sound | Caused by extrathoracic airway obstruction; may be heard on expiration if obstruction is in the subglottic area or trachea, where the sound resembles a wheeze |

| Wheeze | Continuous sound with musical quality heard mainly during expiration; often a shorter sound on inspiration | Indicates intrathoracic airway obstruction; results from dynamic compression of large central airways from either peripheral or central airway obstruction |

| Grunting | Episodic, short expiratory sound | Caused by partial closure of the glottis during expiration |

| Rattly breathing | Coarse, irregular sound heard mainly during inspiration; rattles can be felt through hands placed on the chest | Indicates secretions in the trachea or major bronchi |

Palpation

Position of the Trachea

You can accurately assess the position of the trachea in the suprasternal notch by using two fingers when examining older children and one finger for younger children (Fig. 9–9). Tracheal shift indicates that the mediastinum has shifted, signifying either change in volume or pressure in one hemithorax. The mediastinum can be either pushed or pulled to one side, depending on the location and nature of the abnormality. Other aspects of the physical examination usually shed light on the underlying problem, so do not rush to order imaging studies when you detect tracheal shift.

Auscultation

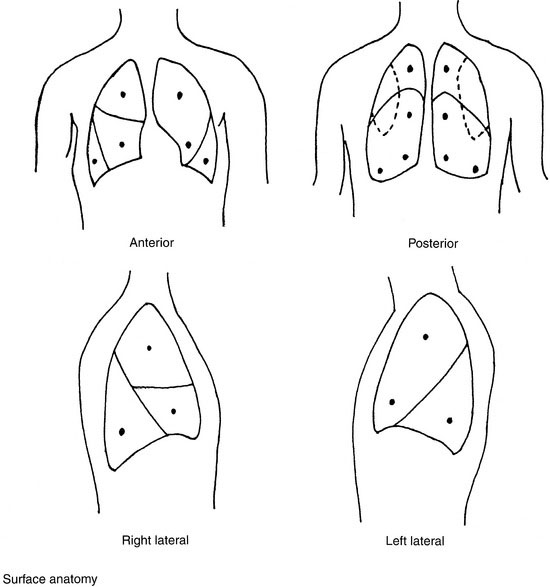

Auscultation over each segment of both lungs is neither practical nor necessary in most circumstances. You should know the surface anatomy of the pulmonary lobes and listen over each one (Fig. 9–10).

FIGURE 9–10 Surface anatomy of the pulmonary lobes and suggested auscultation sites (indicated by solid circles).

Always compare the two sides of the chest during auscultation, characterize the breath sounds, and then listen for adventitious sounds. Determine whether the breath sounds are normal, increased, or decreased in intensity, and describe their quality. Always note any asymmetric differences. The closer the stethoscope is to a larger airway, the more audible and tubular the note will be; these differences are best appreciated by listening during expiration. Always avoid auscultating through clothing. The bronchial breath sounds heard over an area of consolidation or atelectasis illustrate the improved transmission of sound through solid or airless tissue (Table 9–4). Note any adventitious or “extra” sounds, using the descriptions in Table 9–5.

| Sound | Quality | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Tracheal | “Tubular,” high pitched | Heard during inspiration and expiration |

| Bronchial | Has a tubular quality that is less pronounced than in tracheal breath sounds | Heard on inspiration and expiration |

| Bronchovesicular | Pitched slightly higher than vesicular breath sounds | Heard mainly on inspiration, but an early low-pitched note may be heard on expiration |

| Vesicular | Softer, lower pitched | Heard in axillary area and lung bases; heard on inspiration and little heard on expiration |

TABLE 9–5 Adventitious Sounds in the Chest

| Sound | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Crackles/crepitations (formerly known as rales) | Short, crackling, nonmusical sounds heard on inspiration or expiration | Fine inspiratory crackles due to alveolar or bronchiolar disease that has allowed collapse of the peripheral airway, leading to a crackle as it gradually opens and a thin film of fluid bursts; coarser inspiratory or expiratory crackles may arise from air bubbling through mucus in larger airways, the auscultatory finding in a child with rattly breathing |

| Wheezes | Continuous musical, usually expiratory sounds produced by air moving past an obstruction or a narrowing airway | Distinguishing between high-pitched (sibilant) and low-pitched (sonorous) wheezes is probably unnecessary because it may reflect differences only in flow rates; wheezes arise from larger bronchi because air velocity in smaller airways is too slow to produce a musical sound |

| Friction rub | Harsh grating sound synchronous with respiration, indicating friction on movement between the two layers of pleura | Usually easily distinguished from a pericardial friction rub |

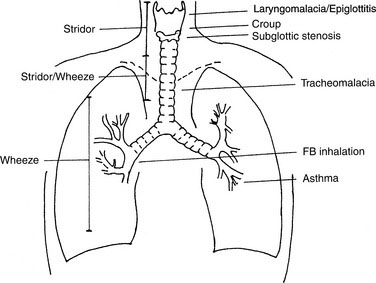

Differentiating extrathoracic from intrathoracic airway obstruction

Localizing the site of an obstruction in the respiratory tract can be both challenging and rewarding in children (Fig. 9–11). Remember that although the airway extends from the nose to the bronchioles, the anatomic site of an obstruction can be determined using the following simple clinical guidelines:

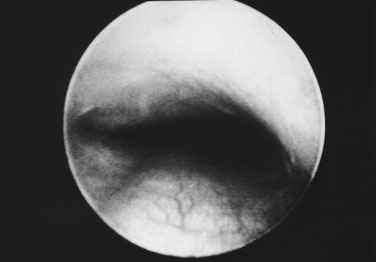

Tracheomalacia and Laryngomalacia

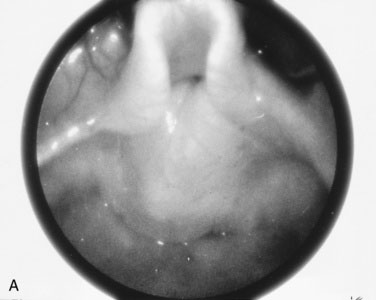

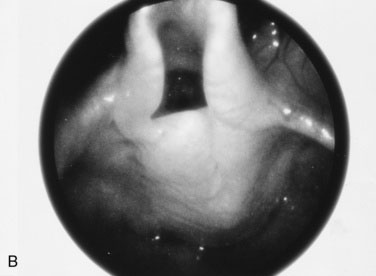

Tracheomalacia is a term used when a portion of the trachea is unusually soft (Fig. 9–13). Tracheomalacia usually occurs in children with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, but it also can arise as a result of a vascular compression, usually by an anomalous artery. Tracheomalacia sometimes occurs without any associated abnormality. The soft area of the trachea is more collapsible and causes a rather coarse inspiratory stridor. A vibratory expiratory stridor, or occasionally a wheeze, often is heard in these patients. When the child coughs, the more easily collapsible soft area of the trachea generates a loud, brassy sound, best described as the “supermarket cough” because parents remark that their child draws immediate attention from other shoppers when they hear the loud, harsh cough. Full evaluation, including fluoroscopy and bronchoscopy, may be required to establish the exact nature of the disorder and to guide management. A loud vibratory cough without stridor or any other associated symptoms occasionally is heard in some older children and is of no clinical significance.

Direct examination of the larynx is required only in the presence of atypical features (Fig. 9–14). In most cases, the only treatment required for laryngomalacia is reassuring the parents about the condition’s benign, self-limited nature. Parents should be told that the noise will get worse when the child has respiratory infections. Because laryngomalacia and tracheomalacia are quite distinct in both origin and clinical presentation, the use of the term laryngotracheomalacia is inappropriate.