chapter 4 Evaluating the Newborn

Diagnostic Approach

Obtaining the History

Table 4–1 lists the important issues to ask about when obtaining any antenatal history.

TABLE 4–1 Significant issues to ask about when taking the History for a Newborn

| Mother’s past pregnancies and their outcome | No. of pregnancies |

| Stillbirths | |

| Abortions | |

| Neonatal deaths | |

| Cesarean sections | |

| Specific concerns that parents may have about current pregnancy because of past experiences | |

| Preexisting systemic illness in mother and maternal medications | Hypertension |

| Depression | |

| Diabetes | |

| Seizure disorder | |

| Thyroid disease | |

| Cardiac disease | |

| Metabolic disorder (phenylketonuria) | |

| Genetic history | History of inherited disorders |

| Consanguinity | |

| Unexplained neonatal deaths in the family | |

| History of current pregnancy | Date of last menstrual period |

| Use of assisted reproductive technologies or fertility treatments | |

| Estimated date of conception by dates (and by ultrasonography if early ultrasonogram [9–13 weeks] available) | |

| Results of ultrasonography, amniocentesis, cordocentesis, chorionic villus sampling | |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes | |

| Note maternal weight gain and blood pressure, fetal growth, blood type | |

| History of alcohol use, drug use (prescribed or illicit), cigarette use | |

| Group B Streptococcus status (if known) | |

| History of maternal surgery during pregnancy | |

| Concerns about placenta (e.g., placenta previa or thickening) | |

| Use of magnesium sulfate, betamethasone | |

| Current labor and delivery | Induced or spontaneous labor (if induced, why?) |

| Time of rupture of membranes and quality of amniotic fluid (bloody, meconium-stained) | |

| Length of second stage | |

| Use of medications (analgesics and time prior to delivery) | |

| Intrapartum fever and antibiotics | |

| History of fetal distress | |

| Presentation (vertex, breech, transverse) | |

| Vaginal or cesarean delivery (if cesarean, why?) | |

| Use of forceps or vacuum extraction | |

| Adaptation to extrauterine life | Apgar scores |

| Resuscitation needed? If so, what and for how long? | |

| Need for naloxone |

Approach to Physical Examinations of the Newborn: When, Why, and How

The first examination

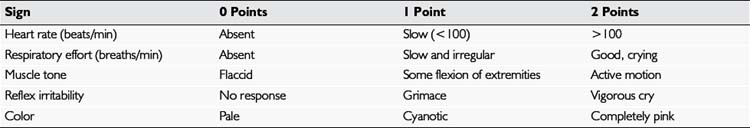

The method used almost universally in delivery rooms to evaluate the central nervous system (CNS) status and general adaptation of the neonate to extrauterine life is the Apgar score. This scoring system, summarized in Table 4–2, evaluates the baby in five different respects: heart rate, respiration, color, muscle tone, and reflex irritability (response to stimulation). These signs are usually evaluated at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth. The Apgar score is the total of the baby’s scores for each of the five signs. To be consistent, have the Apgar score recorded by an experienced clinical observer whose principal responsibility is caring for and evaluating the baby. Because inter-observer variation in scoring may be considerable, experience is essential. Evaluate the signs at exactly 1 minute and 5 minutes to establish the score, especially in relation to muscle tone and reflex irritability. The latter is usually elicited by firmly stroking the sole of the foot; the appropriate response to this stimulation is a vigorous cry.

Clinical Observations and What They Mean

Encourage the parents to participate as much as possible in the examination by undressing the baby, holding the baby on the lap or the bed, and providing a stabilizing finger for the baby to grasp (Fig. 4–1). The first part of the examination is the most important. Do not touch the baby except to remove all clothing gently. You may wish to leave the diaper on until you are ready to examine the lower portion of the baby. The baby should be undressed, warm, and well illuminated and should be helped to feel stable and secure on the examining surface. Improving the baby’s stability and relaxation by letting him or her grasp the parent’s or your finger allows an immediate appreciation of the strength of the baby’s reflex grasp and reduces the tendency for instinctive startle reflexes that occur when the baby feels unstable and rolls on the examining surface.

Primitive Reflexes

Moro reflex

Newborns often demonstrate the Moro, startle, or embrace reflex spontaneously when they are suddenly moved, exposed to a sudden loud noise, given the feeling of falling, or feel unstable on a flat surface. You can most reliably elicit this reflex by allowing the infant’s head to drop (while supporting it gently) below the level of the rest of the body while the baby is in a reclining position. The baby extends the arms suddenly and rapidly with the hands open, then brings them back together more slowly in a movement that looks like an embrace. The initial rapid movement may be accompanied by a grimace or cry (Fig. 4–3). Symmetry of movement is important. Weakness of one arm (e.g., in an infant with brachial plexus injury) results in an asymmetric Moro reflex.

Palmar grasp

Find the palmar grasp by placing your index fingers in each of the baby’s open hands; the baby’s fingers should close around your fingers with strength enough to lift the baby’s body part of the way off the bed or table (Fig. 4–4).

Plantar grasp

A strong plantar grasp usually can be demonstrated if you place your thumb on the sole of the baby’s foot in the space under the toes (Fig. 4–5).

Placing and propulsive (stepping and walking) reflexes

If there is any doubt about the integrity of the baby’s CNS, either because of the history (difficult labor, delivery, traumatic procedures, or birth asphyxia) or because of associated physical findings, such as an abnormal cry, major deformities, or malformations, a more complete neurologic examination should be conducted (see Chapter 13).

Weighing and Measuring

For the physician’s and the parents’ records, it is important to (1) measure the baby’s head circumference, length, and weight accurately and (2) assess the nutritional status. Measure the head circumference, preferably with a disposable tape measure, around the largest occipital-frontal diameter across the forehead, just above the eyes, and over the most prominent part of the occiput (Fig. 4–6). Head circumference normally measures 33 to 37 cm in a full-term infant. If a baby’s head circumference measures slightly above or below the normal for age, check the parents’ head circumferences before “pushing the panic button.” Benign familial megalencephaly, a normal variant, is the most common cause of a larger than average head. The condition can be verified by checking the head circumference of both parents. Megalencephaly is usually handed down by the father.

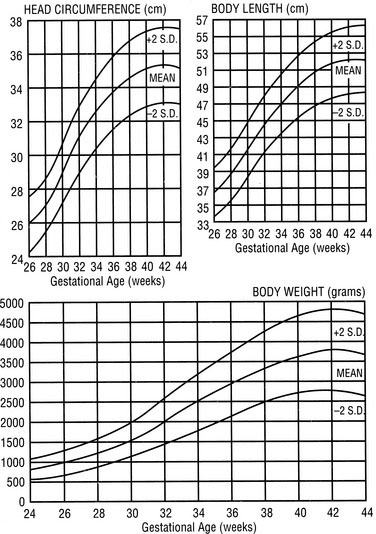

Measuring length is important, and it must be done accurately. Measuring length with a tape measure or by making pencil marks on a piece of paper underneath the baby is notoriously inaccurate. Accurate length measurement is best accomplished by using one of the commercially available fixed measuring devices, with the baby lying supine and the head touching a fixed object (Fig. 4–7). Extend the baby’s body and legs and hold them flat; record the resulting length, which is normally 47 to 55 cm. Plot the weight, length, and head circumference on a sex-appropriate fetal growth chart (Fig. 4–8) to see whether the baby is (1) within the normal range for gestational age and (2) proportional in terms of head circumference, length, and weight.

FIGURE 4–8 Growth charts for the newborn male (in Nova Scotia). Measurements are related to gestational age.

(From Lubchenco LO, Hansman M, Dressler M, Boyd E: Intrauterine growth as estimated from liveborn birth weight data at 24 to 42 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics, Vol. 32, p. 794, Figure 1, Copyright 1963.)

Assessing Gestational Age

The full-term baby has deep creases crisscrossing the sole of the foot, from the ball to the heel (Fig. 4–9). The preterm baby does not have these creases.

FIGURE 4–9 A, Typical sole creases of a full-term infant. B, Comparatively smooth sole of a premature infant.

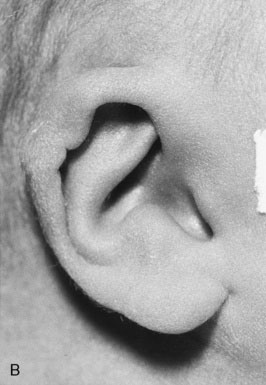

The preterm baby’s ear has fewer folds and is more pliable than the springy, cartilaginous, well-formed ear of the full-term infant (Fig. 4–10).

In the full-term male infant, the scrotum is full, rugated, and pendulous, with the testes fully descended; in the preterm baby, the scrotum is smaller and smoother, and the testes are either high in the scrotum or in the inguinal canal (Fig. 4–11). The testes are usually palpable in the upper scrotum by 36 weeks’ gestation and are fully descended by 40 weeks.

The preterm female infant has relatively prominent labia minora and small labia majora, whereas in a full-term girl, the labia majora fully cover the vaginal opening and obscure the labia minora (Fig. 4–12).

More detailed systems exist for evaluating and scoring the gestational age of infants, the most popular of which was described by Dubowitz in 1970 and refined by Ballard and associates in 1991. The Dubowitz/Ballard Examination for Gestational Age is a useful tool for which considerable practice and experience are required to achieve accuracy. The scale involves assessing six neurologic and seven physical criteria on a numerical scale and calculating a total score. That score is then matched to a table giving approximate gestational age. The physical criteria, including those already described, are more accurate than the neurologic criteria, because the neurologic score is falsely low in a sick or neurologically compromised infant, as well as in many preterm infants. (See http://www.chw.org/display/PPF/DocID/23273/router.asp#3273.)

The Head

Newborns’ heads vary considerably in shape and symmetry, depending on intrauterine position and pressures, presentation at delivery, and the amount of molding that has taken place during labor and delivery. A baby born by breech delivery or cesarean section characteristically has a fairly round, symmetric head, whereas the head of a baby born by vaginal vertex delivery is usually elongated occipitally, with some overriding (overlapping) of the sutures and possibly a caput succedaneum (Fig. 4–13) or a cephalhematoma. A caput succedaneum is a collection of subcutaneous edema fluid caused by constricting pressure during passage through the birth canal; it normally resolves within the first few days of life. A cephalhematoma is a subperiosteal collection of blood limited by the periosteal attachments to the area over a single bone of the skull. Soft and fluctuating, it feels like a fluid-filled cyst, and it may last for several weeks, gradually getting smaller. During its resolution, a cephalhematoma usually calcifies initially at the edges, giving the impression on palpation of depression of the skull in the center with an eggshell-like bony margin, raising fears of skull fracture. In general, the baby’s skull is smooth without any obvious depressed areas. Depressed fractures are rare but can occur.

FIGURE 4–13 Caput succedaneum. The subcutaneous edema was caused by the pressure of the passage through the birth canal.

(From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW: Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, 5th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2007.)

The eyes

Examination of a newborn baby’s eyes may seem difficult at first, but as with other aspects of the examination, it is surprising how much you can learn without touching the infant. First, establish that both eyes are of normal size with normal-appearing corneas, pupils, and sclera. Make sure that red reflexes are present bilaterally and that there are no anterior chamber hemorrhages, visible cataracts, or other malformations of the lens or iris. The main ingredient required for success in this examination is patience. See Chapter 8 for details.

Small subconjunctival scleral hemorrhages, which are seen commonly in newborns (Fig. 4–14), are caused by increased intravascular pressure during delivery. They are unsightly but harmless and usually disappear in a few days. If you do find some hemorrhages, reassure the parents immediately.

FIGURE 4–14 Scleral subconjunctival hemorrhage, which is a common, transient, and harmless phenomenon in newborns.

Getting a good look at a newborn’s eyes is not always easy, but several useful tricks can make it less frustrating for all concerned. Babies open their eyes in a darkened or dimly lit room more readily than in brightly lit surroundings. In the quiet alert state, they often open their eyes spontaneously. Truly quiet and alert babies may fix their gaze on you, looking at you rather than through you (see Chapter 8). You can establish that the baby will follow your face through an arc of at least 90 degrees. This finding, coupled with the presence of bilateral red reflexes, gives good first-line reassurance about the baby’s vision.

Although it sometimes is possible to separate the baby’s eyelids with your fingers, this practice is not recommended. In the first place, during the first few hours of life, the eyelids are often covered with slippery vernix, making it no easy task to get a grip. Second, this approach often makes babies cry and try to close their eyes even more tightly. If it is impossible to catch the baby in the quiet alert state, try taking advantage of the vestibular reflex as a means of getting an infant to open his or her eyes. Pick the baby up, supporting the head with a hand, and hold the baby upright with the face at your eye level; then slowly rock the baby back and forth, toward and away from you (Fig. 4–15). If the baby is quiet and not crying, the eyes usually open for a few moments at least, letting you check the red reflexes and pupillary responses. Do not be surprised if the baby appears to have a strabismus (i.e., to be “cross-eyed”), because conjugate movement of the eyes in young infants is only intermittent.

The ears

Examination of a newborn’s ears generally is limited to the external ear and outer ear canal. Observe the formation of the external ear—its folds, stiffness, symmetry, and placement on the head—and the patency of the ear canal. It is possible to examine the ear canal and tympanic structures with an otoscope, but this procedure usually is not part of the routine physical examination of newborns. You should, however, examine the ear canals carefully in any infant who has any malformation of the external ear. The newborn’s eardrum is placed more horizontally than in older children and requires careful orientation to see it; moreover, the ear canals often are blocked with vernix and amniotic debris during the first few days of life, making it difficult to visualize the eardrums. External ear malformations, such as low-set ears, abnormalities in shape or formation, skin tags, and pits, are important both cosmetically and as indicators of possible associated congenital malformations that may be part of specific syndromes (see Chapter 5).

The mouth

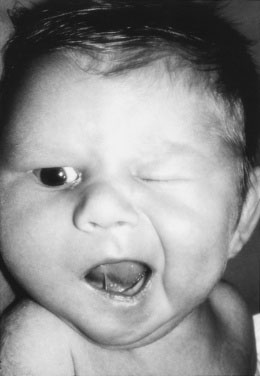

If the baby happens to cry during the examination, seize this opportunity to examine the mouth. Check whether the palate is intact. Although in many babies the tongue appears to be tethered to the bottom of the mouth by a frenulum that sometimes reaches the tip of the tongue (“tongue tie”), it is always mobile enough to allow the baby to suck and to establish breast-feeding, which are all that is necessary at this age (Fig. 4–16). Cutting the tongue frenulum used to be a common practice but is no longer considered a useful or acceptable procedure. True tongue tie is exceptionally rare, if it exists at all.

Stroke the face beside the baby’s mouth with your finger to elicit the rooting reflex, in which the baby turns the head toward the finger and opens the mouth as if to grasp a nipple (Fig. 4–17). By putting a finger in the baby’s mouth, you can elicit the suck reflex and check the palate. It is unnecessary to test for the gag reflex unless there are specific concerns about neurologic function. When the baby cries, note whether the mouth and face are symmetric. Asymmetric crying may be the one and only tip-off to a unilateral facial palsy that is not apparent when the baby is quiet. In a baby with unilateral facial palsy, the affected side does not move as well as the other side, the nasolabial fold remains flat, and the corner of the mouth droops (Fig. 4–18). Facial palsy often is associated with compression of the facial nerve during delivery (i.e., by forceps). The majority of facial palsies resolve without permanent damage.

The Neck

The Chest

Feel the peripheral pulses. Always palpate the femoral region to be certain that femoral pulses are present, are equal bilaterally, are equal in strength to the brachial pulses, and are of normal volume. If the pulses are present at the initial examination, do not assume that they are still there at the next examination; recheck the femoral pulses at each examination of the baby for the first year. Failure to check and recheck the femoral pulses in the newborn is a capital crime. The arteries are found at the lateral side of the femoral triangle just below the inguinal ligament (Fig. 4–20). Make sure that you have really felt the femoral pulsations. If you only think you have felt them, you have not actually felt them. Absence or weakness of femoral pulsations indicates possible aortic coarctation and warrants an urgent cardiology consultation. Provide a record of four-limb blood pressure measurements to the cardiologist for the examination. Adequate peripheral perfusion manifests as warm pink extremities with good capillary refill.

The Abdomen

The Genitalia

Investigations for ambiguous genitalia may include chromosome analysis, urine and blood hormone analyses, and internal examination by ultrasonography or radiography with contrast enhancement. Often, consultations with an experienced pediatrician or neonatologist, endocrinologist, geneticist, and pediatric urologist are needed to help make an accurate diagnosis. (See Chapters 5 and 16 for detailed discussions of this issue.)

Hernias And Hydroceles

Hydroceles are common in newborn boys (see Chapter 12). An isolated hydrocele without hernia usually disappears within weeks or months and rarely requires repair. If you find a hernia, make sure that it is easily reducible; if not, consult a surgeon immediately, because early repair may be required. Hernias in girls are rare and always call for careful palpation for aberrant gonads and for exclusion of sexual ambiguity before and during surgical exploration.

The Hips

Do not assume that the hips are not dislocated or subluxable in a baby who kicks the legs vigorously. Congenital dislocation of the hip occurs in approximately 1 in 500 to 1 in 1000 babies. If diagnosed early, the condition is treatable with good results (Fig. 4–21).

FIGURE 4–21 A and B, Proper technique for examining the newborn for congenital subluxation or dislocation of the hip.

The Extremities

Now move your hands down over the baby’s legs to judge symmetry and equality of length, quickly checking the number of toes and for the presence or absence of syndactyly on each foot. Slight syndactyly of the second and third toes is a common minor congenital anomaly without special significance (Fig. 4–22). If you have not already looked at the creases of the soles of the feet to assess gestational age, now is a good time to do so. Most normal newborns have slight bowing of the legs, reflecting intrauterine position. This bowing disappears gradually as the infant gets older. Often, if the baby’s legs are “folded up” accordion style, gentle pressure on the soles of the feet induces the baby to resume the intrauterine posture, allowing a greater appreciation of how the legs became bowed.

The Back

Now, turn the baby over and examine the back. Check the creases at the thigh-buttock area for symmetry. Asymmetry may reveal early signs of leg shortening associated with congenital dislocation of the hip. Examine the midline of the back particularly carefully, because midline congenital defects on the dorsal surface may signal important internal anomalies. Starting at the lower end, look at the top of the cleft between the buttocks at the base of the spine. Many babies have a pilonidal dimple in this area (Fig. 4–23) that will disappear and has no special significance. If there seems to be no bottom to the dimple or if it appears to be a sinus tract, further investigation (with ultrasonography) should be initiated, because the tract may communicate with the spinal canal and be associated with other malformations. Any hemangioma, lipoma, or tuft of hair that crosses the midline of the lower back carries a high probability of being associated with an internal structural spinal abnormality, such as spina bifida occulta or tethering of the spinal cord by a bony spicule or fibrous band (diastematomyelia). Run a finger up and down the spine, noting lumps or gaps between the spines or gaps where there should be spines, which could indicate spina bifida or lipomeningocele. Continue the examination right up to the base of the neck and the occiput, looking for defects. Neural tube defects may be small, but they are always in the midline. Frequently there is a small, flat area hemangioma at the nape of the neck, popularly known as “stork bite,” which is insignificant; it will become less obvious as the infant gets older, either by disappearing or by being covered by hair.

Skin of the Newborn

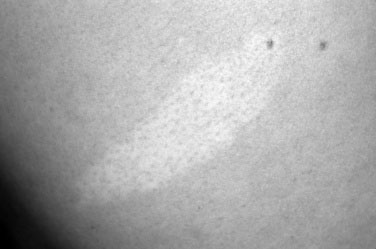

Pigmented and depigmented lesions

Areas of depigmentation may be significant because they may be the earliest and, for a time, the only manifestations of tuberous sclerosis, a progressive degenerative neurologic disease. The typical lesions often occur in the shape of an ash leaf (Fig. 4–24) and may occur singly or in multiples. Their appearance is intensified by examination under ultraviolet illumination (a Woods lamp).

American Academy of Pediatrics. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation (clinical practice guideline). Pediatrics. 2004;114:297-316.

Ballard J.L., Khoury J.C., Wedig K., et al. New Ballard score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr. 1991;119:417-423.

Canadian Paediatric Society. Guidelines for the detection, management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in term and late preterm newborn infants (35 or more weeks’ gestation)—summary. Pediatr Child Health. 2007;12:401-407.

Rabi Y., Yee W., Chen S.Y., et al. Oxygen saturation trends immediately after birth. J Pediatr. 2006;148(5):569-570.