223 Evaluating Pediatric Critical Care Practices

A Historical Perspective on Quality

A Historical Perspective on Quality

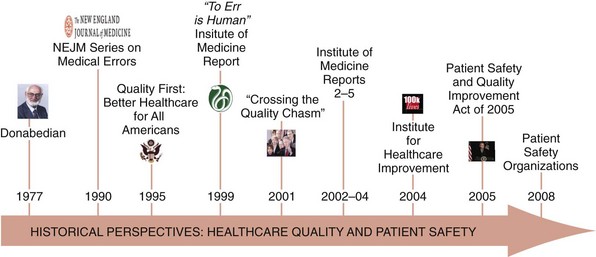

Quality in health care has received increased focus over the last 30 years, beginning with Donabedian’s influence demonstrating that the fundamental concepts of structure, process, and outcome were as important to health care as they were to other industries (Figure 223-1).1 Since then, focused efforts to advance the concept of quality in health care have been performed. In the early 1990s, a series of articles in the New England Journal of Medicine quantified adverse events and helped disentangle the elements of patient harm and its relationship to risk management.2–4 A few years later, President Clinton, through executive order, chartered a commission to investigate healthcare quality more broadly.5

Despite these and a variety of other prominent efforts, discussion regarding quality in health care remained relatively stagnant until the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) series of reports.6–9 The first IOM report, “To Err is Human,” provided a wakeup call for the healthcare industry to consider how patients may be harmed.6 This was followed by “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” which defined six “Aims for Improvement.”7 These aims included safety, effectiveness, equity, timeliness, patient centeredness, and efficiency and helped establish a framework through which clinical services, including those delivered to the critically ill child, could be evaluated.10

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), among other groups, became instrumental in providing clinicians with tools to help them focus on improvement work by defining and measuring what was to be improved and by when.11 Efforts aimed at improving reporting and learning from adverse occurrences were noticed when President Bush signed the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act, which would become operationalized in part through patient safety organizations.12 More recently, with healthcare reform taking shape, other considerable advances including medical homes, accountable care organizations, and pay for performance are likely to take on additional significance and set the tone for healthcare quality for years to come. This will create important opportunities and challenges for advancing care for critically ill children.10

Systems of Care

Systems of Care

Traditional engineering approaches focus on how systems work rather than on understanding the ways in which they fail or the effects of failure.13 There are several aspects of system design and maintenance that can affect the likelihood of failure. This is a fundamental distinction to how quality is viewed in health care.13 First, clinicians often approach quality improvement from the perspective of risk rather than the perspective of reliability. Mortality and morbidity conferences, peer review meetings, and root-cause analysis all tend to focus on what went wrong in retrospect and the elements of failure rather than on the system’s reliability.13 Second, pediatric critical care clinicians function in complex systems of care yet have little training or experience in how to design and organize those complex systems to ensure that the needs of the critically ill child are met.13 Routinely, providers will repetitively use “workarounds” rather than redesigning processes to be safer and more efficient. Finally, in contrast to the engineering approach, clinicians are very interested in the effects of system failure, which in clinical parlance are the outcomes of care. Whereas outcomes are important, several recent efforts in health care have also demonstrated the importance of managing the processes of care.14 The best examples of these efforts in pediatric critical care are evidence-based clinical guidelines, checklists, and “bundles” of care, which represent tactical opportunities to specify how care should be delivered to arrive at the desired outcomes.

Designing for Evaluation

Designing for Evaluation

Program Elements

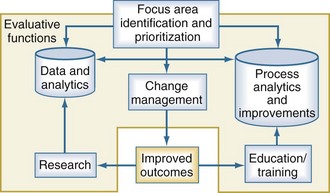

The ability to evaluate clinical services, including pediatric critical care services, depends upon how well the evaluation program is built and implemented. When considering complex systems, it is often helpful to begin by identifying the focus areas for evaluation and improvement and prioritizing those based on the desired impact. Quality improvement and evaluation rely upon three critical and interdependent functions: data and analytics, process improvement techniques, and change management principles (Figure 223-2). Each one of these functions is important in their own right, but none of these is sufficient individually to accomplish successful improvement. The use of data is fundamental for improving quality. Data should be objective, easy to measure, accurate, and establish a baseline of performance upon which improvement efforts can be compared when the evaluation is completed. The analytic component is equally important. Effective programs will move past mere descriptions of data and use important analytic techniques to support their inferences. Clinical processes are the interactions between providers and their patients and providers with one another. A variety of techniques can help with the description of clinical processes, including workflow analysis, flow charting, and time motion studies. These important data elements can then be compared and analyzed using value-stream mapping to eliminate waste and streamline the process, making the care more efficient. More recent efforts evaluating teamwork principles and their impact on outcomes are beginning to emerge.15,16 Change management is fundamental to every improvement process. In addition to managing the changes in process, managing the transition from a current state to some future state requires attention to relationships, commitment, and communication for the team and its members.

Sustaining Improvements

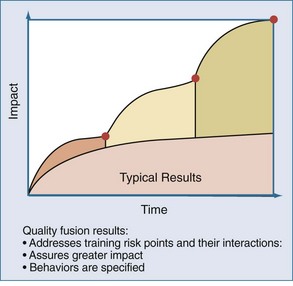

In contrast, when systems are designed around specified behaviors, and the risk points that allow workarounds and adaptive behaviors to emerge are identified, higher levels of performance can be achieved. This approach involves the fusion of different team members’ perspectives over time. For example, when considering the evaluation of results of a recent project to improve bloodstream infections, the PICU team invited members of the operating room suite and hematology-oncology service to participate in the meetings. The input of these “internal consultants” provided the PICU team with an opportunity to learn and apply useful practices from other clinical contexts with relevance to their patient. The use of this so-called quality fusion approach (Figure 223-3) provides the PICU with a greater impact on the initiative under study and provides important sustainability when attention is diverted to the next improvement project.

Evaluation Domains at the Unit Level

Evaluation Domains at the Unit Level

Safety

Since the IOM’s report on medical errors and patient safety highlighted the problem of iatrogenic injury in hospitalized inpatients, numerous stakeholders have begun to focus on reducing medical errors as a means of improving patient safety and reducing the harm associated with the delivery of health care.7 Adverse patient occurrences are inevitable in the high-risk environment of the PICU, but interventions aimed at reducing these adverse events can be designed once one understands the types of errors and the circumstances that contribute to them.

Error Classification

Different classification schemes for medical errors have been developed. Brennan and colleagues classified adverse events in medical practice as operative and nonoperative.7 McClead and Menke, in their classification system for neonatal ICUs, included both the investigation of complications associated with new or unproven technologies and the study of human error, which is relevant to the understanding of a just culture where providers are held accountable for risky behaviors in the care process.17–18 The identification of critical incidents provides opportunities to make system improvements. Finally, the IOM categorized medical errors based on their diagnosis, treatment, prevention, communication, and equipment failures.6 These categories are relevant for the evaluation of pediatric critical care services.

Diagnostic Errors

The autopsy has been used as a technique to enhance quality assurance programs in medical care. Diagnostic errors uncovered at autopsy that result in the primary cause of death or affected patient outcome are important to consider.19 In three single-institution studies of critically ill adults, autopsies revealed diagnoses that would have changed antemortem management and affected outcome in 10% to 27% of cases.20–22 In children, the rate of missed diagnoses that affected outcome was estimated at 7% in one study.23 In the PICU, one study identified major diagnostic errors that would have affected outcome in 5% of patients; in an additional 25% of cases, there were missed diagnoses that were not believed to be clinically meaningful.24 Importantly, iatrogenic injury was a major subset of these missed diagnoses, occurring 17% of the time.24 Thus, autopsy remains an important tool for identifying diagnostic errors and deaths related to iatrogenic injury in the PICU. It also provides an opportunity to enhance provider education and training related to diagnostic dilemmas.

Treatment Errors

Medication Errors

Medication administration occurs frequently in the treatment of critically ill children and provides considerably more opportunities for medication errors and adverse drug events (ADEs). Among hospitalized children, ADEs are common, and the PICU is an important setting for their occurrence.25–26 Specific medication classes are prone to errors, including sedatives, vasoactive infusions, and parenteral nutrition. One useful and cost-effective strategy to improve medication safety in the PICU is to have a unit-based pharmacist who can intervene to adjust dosages, provide drug information, contribute to management decisions, and monitor complications of medication therapy. This has become an increasingly important opportunity to be able to provide high-quality critical care services to children.27

Nosocomial Infection

Acquired infections are important contributors to morbidity, mortality, and cost in the PICU.14,28–32 Recent efforts have expanded our knowledge of the incidence, prevalence, risk factors, costs, and methods of improving bloodstream infections in the PICU.14 The importance of these efforts is the ability to demonstrate how care can be improved when providers use data to drive system changes.

Risk factors for nosocomial infection in the PICU include severity of illness, postoperative status, and device use.31–34 Specific investigations into the types of nosocomial infection (e.g., urinary tract, pneumonia), specific organisms (e.g., influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), specific PICU patient populations (e.g., cardiac surgery, burns), and specific procedures (e.g., mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) have been performed. These studies provide insight for the development of directed strategies to reduce nosocomial infection rates and their associated morbidity and mortality in PICUs. These strategies include more stringent infection control policies, reduction of colonization with resistant organisms, and scheduled rotation of prescribed antibiotics.35–37 Perhaps the most important opportunity to reduce infections is the removal of unnecessary devices including urinary catheters, central venous and arterial catheters, and ventilators as soon as they are not longer needed for the child’s care.14,31,32

Procedures

Interventional procedures are an important component of pediatric critical care practice. They provide the intensivist with the means to address a child’s failing organ systems, but they are also associated with risk. Procedural risks are associated with both the insertion and maintenance of these devices. For example, tracheal intubation is associated with potential complications from laryngoscopy, failed intubation attempts, esophageal intubation, damage to the teeth, and hypoxemia.38–39 In addition, the risks from unintended extubation for the child with respiratory failure are significant. PICUs can address their rates of adverse occurrences related to both the performance and maintenance of commonly performed invasive procedures like central venous access, mechanical ventilation, arterial cannulation, and intracranial pressure monitoring. Collaborative efforts that share best-practice methods of inserting and maintaining these devices can demonstrably improve the complications associated with these procedures.14

Preventive Errors

In the ICU, considerable evidence has been accumulated regarding prophylaxis for gastrointestinal stress ulcers, deep venous thrombosis, pressure ulcers, and other adverse events.40–41 Efforts have also been made to address prophylactic care more broadly. For example, the Prophylactic Intravenous Use of Milrinone After Cardiac Operation in Pediatrics (PRIMACORP) study was initiated to determine whether the prophylactic postoperative use of milrinone in pediatric cardiac surgery patients improves the outcome associated with low cardiac output syndrome.42

Other Errors

The PICU environment may itself be an independent contributor to patient safety. Two characteristics contribute to the likelihood of errors in the PICU. The first is complexity, or the degree to which system components are specialized and interdependent. Complex systems are more prone to errors. The second characteristic is coupling. Tightly coupled systems have no buffer, and sequences are fixed, whereas loosely coupled systems can tolerate delays or variations in sequencing. Communication errors, equipment failures, system failures, and more recently, problems with teamwork are all associated with complex and tightly coupled systems and can contribute to an unsafe environment in these settings.6 Equipment failures are an obvious and often unavoidable problem related to patient safety. However, communication failures, system failures, and teamwork problems can enhance the likelihood of errors and prevent an appropriate mitigating response when they occur.15–16

Effectiveness

Evidence-based practice incorporates the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values to achieve the best outcomes for patients.7 The clinical practice of critical care medicine is highly variable among practitioners and institutions. Efforts to reduce variability in care are provided by the implementation of practice guidelines and the use of clinical algorithms and checklists.43–44

Private, governmental, and subspecialty organizations have developed numerous guidelines to reduce unnecessary variability in care. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Society for Critical Care Medicine have developed guidelines and policy statements to help improve the care of critically ill children.45–46 Guidelines can be heterogeneous with respect to their creation. At one extreme, results from randomized controlled trials are incorporated into the care guidelines; at the other extreme, the consensus of a group of practitioners is all that is required. This is important, because the success of any practice guideline is dependent on its ability to influence physician decision making.

Efficiency

Economics demands that healthcare resources be delivered in a cost-effective and efficient manner while not jeopardizing quality.47 The achievement of specific outcome goals is a measure of an ICU’s quality. Costs vary with outcome measures. Mortality rates, efficiency rates, lengths of stay, rates of nosocomial infection and readmission, and the presence of a teaching program all impact expenses and reimbursement. Quality at a given level of cost determines the value of a commodity. In this case, the commodity is ICU care.48

The value of an individual ICU is increased by its ability to achieve selected measures of outcome while keeping costs to a minimum. This is concordant with the concept of efficiency as an aim in the IOM’s current model of healthcare quality.7 Intensive care services are a commodity, and those units providing quality care at a reasonable cost, as judged by efficiency and a similar patient mix, will be most appealing. Less efficient ICUs will have to optimize efficiency or have cost-containment strategies imposed on them.48

From a microeconomic perspective, patients who are sicker require more services in the ICU, stay longer, are more likely to die, and cost more to be treated.49–50 This is not new information. However, to balance the issues of cost and quality, ICUs should identify same-strata best-practices ICUs with similar cost drivers (e.g., severity of illness) and operate under a philosophy of “targeted benchmarking” to achieve comparability up to a specified level.51 To accomplish this, clinical scoring systems are frequently used to control for case-mix variables (physiology, diagnoses, etc.) and thus allow for standardized comparisons. Length of stay has become a standard in benchmarking ICU performance and quality, and reducing length of stay is one method of reducing cost, although as a variable itself, length of stay is subject to differences in measurement.52–53 The standardized length-of-stay ratio is that of observed-to-predicted length of stay and is an indicator of resource use adjusted for severity.54 The standardized length-of-stay ratio can be used to compare a particular unit’s performance over time, but it can also be used to determine whether a particular ICU’s resource use is above or below that of similar ICUs.54

Another method of assessing the efficiency of resource use in the ICU is to evaluate unique ICU therapies55–61—that is, those that are best delivered in the ICU, such as mechanical ventilation and vasoactive infusions. Individual ICUs and physicians differ in their monitoring strategies, so monitoring technologies should not be classified as unique therapies.57 The benefits of this approach are that it allows physicians to determine the proportion of low-risk monitor-only patients61 and compare the number of high-risk critical care patients requiring unique ICU therapies. Excess bed capacity leads to a higher ratio of monitored patients to high-risk patients and reduces the efficiency of the ICU.61 Opportunities to evaluate admission and discharge criteria, as well as throughput issues resulting from the inability to transfer ICU patients because of a high hospital occupancy rate, may serve to improve an individual ICU’s efficiency.

Equity

Achieving equity in healthcare quality means ensuring impartial care for populations and individuals that is free from bias related to race, ethnicity, insurance status, income, or gender. This bias may be manifested at two independent levels. First, discrimination may be targeted at the population level before the patient actually reaches a healthcare provider. These problems are primarily ones of restricted access to health care. Second, once patients have accessed healthcare services, they may receive differential treatment based on personal characteristics.7 In its most overt form, this is called discrimination.

Insurance status differences affect access to outpatient physicians, hospital services, and procedures. These differences also affect physicians’ practice patterns and thereby influence resource use and outcome for adult primary care and critical care patients alike.62–64 Insurance status differences apply not only to different types of insurance but also to the method of administering the insurance.64,65 For example, the care delivered under a managed care arrangement is expected to be different from that delivered in a non–managed care environment. However, these differences in care do not necessarily mean that one type of care is worse; it may simply be different.65 Lack of access to needed services may be responsible for delayed disease presentation and avoidable morbidity, which may lead to more severe illness and longer hospital stay.66,67 This is consistent with the observation that patients from lower socioeconomic status have more severe illness on admission to the PICU.68

There are limited data describing the relationship of insurance status to resource utilization or outcome in specific subgroups of critically ill pediatric patients, including neonates and medical and surgical patients.69–73 Insurance status differences in critically ill pediatric medical patients have been demonstrated. After adjusting for illness severity, Medicaid-insured children with acute severe asthma received mechanical ventilation more often and for longer durations and had longer PICU and hospital stays than commercially insured or managed-care patients.73 Children with Medicaid who were hospitalized with diabetic ketoacidosis experienced coma more often and had longer lengths of stay than their commercially insured counterparts.73 Similar insurance status differences can be found among critically ill pediatric surgical patients. Postoperative congenital heart disease patients with Medicaid had higher mortality rates than commercially insured children.71 Medicaid patients experienced complicated appendicitis, including perforation or abscess formation, more often than other patients,73 and they had longer stays. Observed mortality rates among uninsured children with head trauma were higher than those among privately or publicly insured children.72

The IOM was charged with assessing the extent of racial disparities in health care, identifying factors contributing to the inequities, and recommending policies and practices to eliminate them.74 The integration of national efforts to address racial disparities in health care and the work being accomplished in healthcare quality provide opportunities to improve the equity of delivered healthcare services to minority populations.75 Racial differences in health care are evident for adult and pediatric patients. These differences affect access to healthcare services and outcomes.76–83 Intensivists have reason to be concerned about these findings.

The literature regarding racial disparities in critically ill children is not nearly as well established. In a 25-year study of mortality associated with congenital heart disease, black patients had a nearly 20% higher mortality rate than white patients.82 For pediatric patients requiring single-ventricle palliation for congenital heart disease, there was considerably more variation in the age of palliation in black babies than in white babies in a single-institution study. Black pediatric patients with renal failure are less likely than white patients to be wait-listed for kidney transplantation.77 However, in a study of low-birth-weight infants, there were no survival differences between white and black babies.76

Race has been used as a proxy for a number of other socioeconomic factors.84 It has become evident, however, that if meaningful information is to be gained by including racial variables in research, reliable and valid definitions have to be used.84 Race is a relatively nonspecific term that incorporates biological, social, and cultural components that are more than mere physical descriptors and are not consistently considered in the definition.84 As a result, when comparing outcome measures—whether vitality outcomes such as mortality or resource use outcomes such as length of stay—it may be inappropriate to conclude that race is the explanatory variable.84

Timeliness

Timeliness is a marker of the adequacy of processes in the ICU to achieve acceptable outcomes.85 The IOM report characterizes timeliness in two distinctive ways.7 First, the report uses a customer-service focus by addressing such issues as wait times in offices and emergency departments and for diagnostic testing or surgery. The suggestion is that health care providers’ inattention to the flow of patients demonstrates a lack of respect for patients and their families.7 The second focus extends beyond customer satisfaction to include patient outcomes, which are particularly germane to ICUs. The ICU is a valuable resource for critically ill patients, and if ICU resources are unavailable when patients need them, adverse outcomes are possible. In this circumstance, the redesign of clinical processes has a direct effect in ensuring that patients get services when and where they need them. For example, a child who experiences a cardiac arrest in the radiology suite is dependent upon the ability of the institution to provide quick and definitive care in radiology rather than waiting to transport the patient to the ICU and delaying necessary therapies.

Patient Centeredness

The IOM’s aim of patient centeredness helps characterize the interactions between practitioners and their patients.7 A number of terms, including empathy, compassion, needs, and respect, encompass the qualities of patient centeredness and reflect the focus of attention on the patient.7 Additional components that help establish priority areas for the care of individual patients include the provision of information, communication, and education; attention to physical comfort; emotional support by relieving fear and anxiety; and the involvement of family and friends.7 These characteristics constitute what is known as service quality; in contrast, clinical quality is the clinical expertise offered by critical care practitioners. Patient centeredness is more than “service with a smile.” It requires that the processes of care be redesigned around the patient’s and family’s needs and not around the care team’s needs. Both are important to successful care of the critically ill child. The Healthcare Advisory Board identified several broad types of service problems in specialty care (Table 223-1), which remain relevant to the PICU even a decade after their publication.

| Speed of service | Delay in care or excessive waiting time |

| Lack of explanation for delay | |

| Coordination of care | Organization of the environment |

| Availability of appropriate person to answer questions | |

| Respect and courtesy | Staff courtesy |

| Treatment with respect and dignity | |

| Understanding of treatment | Information regarding symptoms, medications, and treatments provided |

| Patient or family included in decisions | |

| Adequate explanations provided | |

| Patient and family listened to | |

| Trust in the provider | Availability of the provider |

| Psychosocial support |

From Advisory Board Company. Service innovations in specialty care: enhancing patient satisfaction with diagnosis and treatment selection. Washington DC: Advisory Board Company; 1998.

Admission to the PICU, especially when emergent and unexpected, is an anxiety-provoking and fearful experience for patients and their families.86–87 For parents, the anxiety is generated from the lack of parental control, the appearance and discomfort of the child, both emotionally and physically, and difficulty communicating with staff.86 The age of the parents and their ability to focus on problems and participate in care are associated with an ability to cope with a critically ill child.88 Coping strategies for parents also include an ability to be supported by the PICU healthcare team. A variety of needs, including emotional, physical, and spiritual, have to be addressed by this support system.89 This can be accomplished by providing accurate information, allowing ready access to the child, and encouraging parents’ participation in their child’s care.86,89 For hospitalized children, anxiety and stress may manifest themselves in behavior problems, especially in those with repeated or prolonged hospitalizations, those who are critically ill, and those with underlying mood or psychological disorders.

If family members perceive that emotional support is inadequate, their satisfaction with the experience and, more important, their long-term viability and cohesion as a family unit are at risk.90 Most families are satisfied with the care their children receive in the PICU and are particularly complimentary about the skill and competence of the nursing staff, as well as the compassion and respect shown toward their children, especially with regard to pain management.91 Attention to adequate pain and anxiety control is an essential component of the care of critically ill pediatric patients.92–94 Pain control addresses a fundamental need and is a compassionate practice that helps allay parents’ anxiety and improves coping.91 The environment of the waiting area and the frequency of physician communication were both identified as detracting from parents’ satisfaction with the PICU experience.91 The family’s ability to function after the ICU admission of a child is dependent not only on their satisfaction but also on the severity of the child’s illness, duration of hospitalization, and location of the hospital.

Evaluation Domains at the Provider Level

Evaluation Domains at the Provider Level

The IOM framework is useful as an organizing principle to understand healthcare quality from the perspective of the discipline of pediatric critical care or the ICU. Providers, when thinking about their own practice, tend to think differently about healthcare quality. Specifically, when providers consider quality, they are often thinking about the care that they, rather than the healthcare team or the ICU, provides. Providers typically believe they provide safe, timely, and effective care that corresponds to the latest evidence. They believe in engaging the child and family in the care and believe they treat all their patients fairly regardless of their personal characteristics or ability to pay. Donabedian’s constructs of structure, process, and outcome are particularly helpful in assisting different providers to identify their role in providing quality care to patients, because they know what is available to them to provide care, they believe they understand their work, and they think they understand what they are trying to achieve (Table 223-2).

TABLE 223-2 Classification of ICU Provider-Specific Quality Components Based Upon Donabedian’s Structure, Process, and Outcome Framework

| Structure | |

| “Bricks and mortar” | |

EBM, evidence-based medicine; ICU, intensive care unit.

* Physician-specific processes.

Structure

Structure is usually interpreted from a “bricks and mortar” perspective. However, while the walls, monitors, equipment, and other technologies are certainly important structural elements, they are insufficient for the optimal delivery of health care. The people—including patients, families, and providers of all disciplines—as well as their knowledge of the child, expertise, and collaboration are needed to effect the best outcomes. In addition, important evidence has linked the organization of the ICU and its management as key determinants of outcome.95,96 When taken together, these elements are the structural components of ICU care to which Donabedian might refer (see Table 223-2).

Process

Clinical processes are the interactions between providers and their patients and providers with one another. Recent evidence highlights the importance of team performance in addition to clinical performance for establishing outcomes.97,98 Whereas nurses, by virtue of their training, tend to be process focused, physicians often lack this skill. Therefore, when asked to address specific process steps like implementing the vascular access bundle, nurses are comfortable with the detailed specification of process, which can actually make a difference in outcomes over time. Attention to the key processes of care are becoming recognized as important in determining outcome, and a number of checklists, guidelines, bundles, and pathways have been developed to ensure compliance with the numerous specification limits established in clinical care.

Outcomes

Finally, outcomes represent the culmination of the healthcare experience. Physicians often focus on outcome measures as the result of their work. In the ICU environment, mortality is a traditional outcome measure that is important, quantifiable, and often discussed. There are other outcome measures of relevance to ICU physicians, including the use of ICU-specific therapies, length of stay, cognitive and physical outcomes, and morbidities arising from the episode of care (see Table 223-2). However, because outcomes tend to be the end result of a series of process steps that are temporally distinct, it is often important for the physician to focus on both components of quality. Outcomes have been held in high regard for considerable time—almost to the exclusion of process measures. Physicians will only be able to improve the quality of care for their patients by focusing on both the process and outcome components of healthcare quality. This represents some of the most fertile ground for generating new knowledge and identifying opportunities to improve outcomes for critically ill children over the next decade.4–5

Clinical Processes and Medical Decision Making

When considering provider-specific processes for improving healthcare quality, different disciplines rely upon the same fundamental aspects of the medical decision-making process (Figure 223-4). These core elements can be thought of through the core processes of the PICU provider as they care for the critically ill child from ICU admission through discharge.

Traditional medical decision making has four iterative steps that assist providers with making decisions for their patients. The first step is data gathering. Physicians use their history, physical examination, diagnostic testing, consultants, and other members of the healthcare team to assist them in ensuring they have collected appropriate data upon which to base their clinical decisions (see Table 223-2). Nurses use their nursing assessment or database, which incorporates all of the nonmedical information the team needs to care for the child and family. The next step is for the physician to interpret the gathered data within the clinical context of the patient. This step involves assembling the collected data to see if it coalesces into a particular pattern and seeing whether that pattern is consistent with the patient’s presentation and findings. When nurses use their skills to perform this function in parallel, a rich conversation can occur when team members assemble during rounds to share the findings of their integrative decision making. For the experienced team, this is often performed rapidly with patterns that are matched against a large mental library of similar conditions and patients. When the team is less experienced, the process is slow and prone to errors. The next step is decision making. Here, the physician may gather additional data by calling a consultant or ordering additional testing. If sufficient data has been gathered, the physician may formulate a medical treatment plan and reevaluate the plan’s success as time progresses (see Table 223-2). The physician may recommend or perform a procedure, the outcome of which may assist with diagnosis or treatment. Nurses will incorporate their nursing diagnoses into the plan, and together the team will act with a comprehensive strategy for providing care. Finally, as the last step of medical decision making, the team must take action. A plan that is incoherent or not acted upon, or a procedure or test that is thought about but not performed, does not help the patient. These four steps allow the clinical team to think through and organize their work (see Figure 223-4).

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:743-752.

Ruttimann UE, Patel KM, Pollack MM. Length of stay and efficiency in pediatric intensive care units. J Pediatr. 1998;133:79-85.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2002.

Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry. Quality first: better health care for all Americans. http://www.hcqualitycommission.gov/, 1998. Available at

Stockwell DC, Slonim AD. Quality and safety in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21:199-210.

Miller MR, Griswold M, Harris JM2nd, et al. Decreasing PICU catheter-associated bloodstream infections: NACHRI’s quality transformation efforts. Pediatrics. 2010;125:206-213.

1 Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring: the definitions of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor, Mich: Health Administration Press; 1980.

2 Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study, I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370-376.

3 Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study, II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:377-384.

4 Hiatt HH, Barnes BA, Brennan TA, et al. A study of medical injury and medical malpractice. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:480-484.

5 Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry Quality First: Better Health Care for All Americans 1998. http://www.hcqualitycommission.gov, May 10, 2010. Accessed on

6 . Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn. LT. JM. Donaldson MS. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

7 Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

8 . Institute of Medicine Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery, Board on Health Care Services. Envisioning the national health care quality report. Hurtado MP. Swift EK. JM. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

9 . Committee on Identifying Priority Areas for Quality Improvement, Board on Health Care Services. Priority areas for national action: transforming health care quality. Adams K. JM. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002.

10 Slonim AD, Pollack MM. Integrating the Institute of Medicine’s six quality aims into pediatric critical care: relevance and applications. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:264-269.

11 http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/IHIOpenSchool/Course+Catalog.htm, May 10, 2010. Accessed on

12 http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/psoact.htm, May 10, 2010. Accessed on

13 Stockwell DC, Slonim AD. Quality and safety in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21:199-210.

14 Miller MR, Griswold M, Harris JM2nd, et al. Decreasing PICU catheter-associated bloodstream infections: NACHRI’s quality transformation efforts. Pediatrics. 2010;125:206-213.

15 Reader TW, Flin R, Mearns K, Cuthbertson BH. Developing a team performance framework for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1787-1793.

16 Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel C, et al. Improving patient safety in intensive care units in Michigan. J Crit Care. 2008;23:207-221.

17 McClead RE, Menke JA. Neonatal iatrogenesis. Adv Pediatr. 1987;34:335-356.

18 http://www.justculture.org/communityinfo.aspx, May 10, 2010. Accessed on

19 Shojania KG, Burton EC, McDonald KM, et al. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: A systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:2849-2856.

20 Blosser SA, Zimmerman HE, Stauffer JL. Do autopsies of critically ill patients reveal important findings that were clinically undetected? Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1332-1336.

21 Gut AL, Ferreira AL, Montenegro MR. Autopsy: Quality assurance in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:360-363.

22 Roosen J, Frans E, Wilmer A, et al. Comparison of premortem clinical diagnoses in critically ill patients and subsequent autopsy findings. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:562-567.

23 Kumar P, Taxy J, Angst DB, et al. Autopsies in children: Are they still useful? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:558-563.

24 Castellanos Ortega A, Ortiz Melon F, Garcia Fuentes M, et al. The evaluation of autopsy in the pediatric intensive unit. Ann Esp Pediatr. 1997;46:224-228.

25 Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285:2114-2120.

26 Raju TN, Kecskes S, Thornton JP, et al. Medication errors in neonatal and paediatric intensive-care units. Lancet. 1989;12:374-376.

27 Krupicka MI, Bratton SL, Sonnethal K, et al. Impact of a pediatric clinical pharmacist in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:919-921.

28 Stover BH, Shulman ST, Bratcher DF, et al. Nosocomial infection rates in US children’s hospitals’ neonatal and pediatric intensive care units. Am J Infect Control. 2001;29:152-157.

29 Grohskopf LA, Sinkowitz-Cochran RL. Pediatric Prevention Network: A national point-prevalence survey of pediatric intensive care unit–acquired infections in the United States. J Pediatr. 2002;140:432-438.

30 Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, et al. Nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E39.

31 Singh-Naz N, Sprague BM, Patel KM, et al. Risk assessment and standardized nosocomial infection rate in critically ill children. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2069-2075.

32 Singh-Naz N, Sprague BM, Patel KM, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial infections in critically ill children: A prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:875-878.

33 Gilio AE, Stape A, Pereira CR, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial infections in a critically ill pediatric population: A 25-month prospective cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:340-342.

34 Yogaraj JS, Elward AM, Fraser VJ. Rate, risk factors, and outcomes of nosocomial primary bloodstream infection in pediatric intensive care unit patients. Pediatrics. 2002;110:481-485.

35 Neely M, Toltzis P. Infection control in pediatric hospitals. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:449-453.

36 Gruson D, Hilbert G, Vargas F, et al. Strategy of antibiotic rotation: Long-term effect on incidence and susceptibilities of gram-negative bacilli responsible for ventilator associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1908-1914.

37 Girouard S, Levine G, Goodrich K, et al. Pediatric Prevention Network. Infection control programs at children’s hospitals: A description of structures and processes. Am J Infect Control. 2001;29:145-151.

38 Kapadia FN, Bajan KB, Raje KV. Airway accidents in intubated intensive care unit patients: An epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:659-664.

39 Cordeiro G, Fernandes JC, Troster EJ. Possible risk factors associated with moderate or severe airway injuries in children who underwent endotracheal intubation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004 Jul;5(4):364-368.

40 Gauvin F, Dugas MA, Chaibou M, et al. The impact of clinically significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding acquired in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2:294-298.

41 Curley MA, Razmus IS, Roberts KE, et al. Predicting pressure ulcer risk in pediatric patients: The Braden Q Scale. Nurs Res. 2003;52:22-33.

42 Hoffman TM, Wernovsky G, Atz AM, et al. Prophylactic Intravenous Use of Milrinone After Cardiac Operations in Pediatrics (PRIMACORP) study. Am Heart J. 2002;143:15-21.

43 Weingarten S. Translating practice guidelines into patient care: Guidelines at the bedside. Chest. 2000;118(Suppl):4S-7S.

44 Bergman DA. Evidence-based guidelines and critical pathways for quality improvement. Pediatrics. 1999;103(Suppl):225-232.

45 Merritt TA, Palmer D, Bergman DA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines in pediatric and newborn medicine: Implications for their use in practice. Pediatrics. 1997;99:100-114.

46 Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4:S1-S75.

47 Pollack MM. Cost containment: The pediatric perspective. New Horiz. 1994;2:305-311.

48 Slonim AD, Pollack MM. An approach to costs in critical care: Macro versus microeconomics. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2286-2287.

49 Klem SA, Pollack MM, Getson PR. Cost, resource utilization, and severity of illness in intensive care. J Pediatr. 1990;116:231-237.

50 Pon S, Notterman DA, Martin K. Pediatric critical care and hospital costs under reimbursement by diagnosis-related groups: Effect of clinical and demographic characteristics. J Pediatr. 1993;123:355-364.

51 Pollack MM, Cuerdon TT, Patel KM, et al. Impact of quality-of-care factors on pediatric intensive care unit mortality. JAMA. 1994;272:941-946.

52 Marcin JP, Slonim AD, Pollack MM, et al. Long-stay patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:652-657.

53 Marik PE, Hedman L. What’s in a day? Determining intensive care unit length of stay. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2090-2093.

54 Teres D. Current directions in severity modeling: Limitations leading to a new definition of a high-performance intensive care unit. In: Irwin RS, Cerra FB, Rippe JM, editors. Intensive Care Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999:2470-2480.

55 Ruttimann UE, Patel KM, Pollack MM. Length of stay and efficiency in pediatric intensive care units. J Pediatr. 1998;133:79-85.

56 Ruttimann UE, Pollack MM. Variability in duration of stay in pediatric intensive care units: A multiinstitutional study. J Pediatr. 1996;128:35-44.

57 Pollack MM, Getson PR, Ruttimann UE, et al. Efficiency of intensive care: A comparative analysis of eight pediatric intensive care units. JAMA. 1987;258:1481-1486.

58 Pollack MM, Katz RW, Ruttimann UE, et al. Improving the outcome and efficiency of intensive care: The impact of an intensivist. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:11-17.

59 Pollack MM, Getson PR. Pediatric critical care cost containment: Combined actuarial and clinical program. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:12-20.

60 Pollack MM, Wilkinson JD, Glass NL. Long-stay pediatric intensive care unit patients: Outcome and resource utilization. Pediatrics. 1987;80:855-860.

61 Pollack MM, Ruttimann UE, Glass NL, et al. Monitoring patients in pediatric intensive care. Pediatrics. 1985;76:719-724.

62 Hafner-Eaton C. Physician utilization disparities between the uninsured and insured: Comparisons of the chronically ill, acutely ill, and well nonelderly populations. JAMA. 1993;269:787-792.

63 Freeman HE, Corey CR. Insurance status and access to health services among poor persons. Health Serv Res. 1993;28:531-541.

64 Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Sirio CA, et al. The effect of managed care on ICU length of stay: Implications for Medicare. JAMA. 1996;276:1075-1082.

65 Friedman B, Steiner C. Does managed care affect the supply and use of ICU services? Inquiry. 1999;36:68-77.

66 Stoddard JJ, St Peter RF, Newacheck PW. Health insurance status and ambulatory care for children. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1421-1425.

67 Gadomski A, Jenkins P, Nichols M. Impact of a Medicaid primary care provider and preventive care on pediatric hospitalization. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E1.

68 Naclerio AL, Gardner JW, Pollack MM. Socioeconomic factors and emergency pediatric ICU admissions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:379-382.

69 Bratton SL, Roberts JS, Watson RS, et al. Acute severe asthma: Outcome and Medicaid insurance. Pediatr. Crit Care. 2002;3:234-238.

70 Demone JA, Gonzalez PC, Gauvreau K, et al. Risk of death for Medicaid recipients undergoing congenital heart surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:97-102.

71 Keenan HT, Foster CM, Bratton SL. Social factors associated with prolonged hospitalization among diabetic children. Pediatrics. 2003;109:222-224.

72 Tilford JM, Simpson PM, Yeh TS, et al. Variation in therapy and outcome for pediatric head trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1056-1061.

73 Bratton SL, Haberkern CM, Waldhausen JH. Acute appendicitis risks of complications: Age and Medicaid insurance. Pediatrics. 2000;106:75-78.

74 Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002.

75 Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold M, et al. Inequality in quality: Addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA. 2000;283:2579-2584.

76 Resnick MB, Carter RL, Ariet M, et al. Effect of birthweight, race, and sex on survival of low birthweight infants in neonatal intensive care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:184-187.

77 Furth S, Garg PP, Neu AM, et al. Racial differences in access to the kidney transplant waiting list for children and adolescents with end stage renal disease. Pediatrics. 2000;106:756-761.

78 Stevens GD, Shi L. Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of primary care for children. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:573.

79 Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:792-797.

80 Einbinder LC, Schulman KA. The effect of race on the referral process for invasive cardiac procedures. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl):162-180.

81 Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618-626.

82 Boneva RS, Botto LD, Moore CA, et al. Mortality associated with congenital heart defects in the United States: Trends and racial disparities, 1979-1997. Circulation. 2001;103:2376-2381.

83 Williams RL, Flocke SA, Stane KC. Race and preventive services delivery among black patients and white patients seen in primary care. Med Care. 2001;39:1260-1267.

84 Schulman K, Rubenstein LE, Chesley FD, et al. The roles of race and socioeconomic factors in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:179-195.

85 Rotondi AJ, Sirio CA, Angus DC, et al. A new conceptual framework for ICU performance appraisal and improvement. J Crit Care. 2002;17:16-28.

86 Meyer EC, Snelling LK, Myren Manbeck LK. Pediatric intensive care: The parent’s experience. AACN Clin Issues. 1998;9:64-74.

87 Huckabay LM, Tilem Kessler D. Patterns of parental stress in PICU emergency admission. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1999;18:26-42.

88 LaMontagne LL, Johnson BD, Hepworth JT. Evolution of parental stress and coping processes: A framework for critical care practice. J Pediatr Nurs. 1995;10:212-218.

89 Farrell MF, Frost C. The most important needs of parents of critically ill children: Parents’ perceptions. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1992;8:130-139.

90 Youngblut JM, Lauzon S. Family functioning following pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1995;18:11-25.

91 Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: Results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1413-1418.

92 Polaner DM. Sedation-analgesia in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:695-714.

93 Macfadyen AJ, Buckmaster MA. Pain management in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:185-200.

94 Bauchner H, May A, Coates E. Use of analgesic agents for invasive medical procedures in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. J Pediatr. 1992;121:647-649.

95 Pollack MM, Koch MA, NIH-District of Columbia Neonatal Network. Association of outcomes with organizational characteristics of neonatal intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1620-1629.

96 Pronovost PJ, Thompson DA, Holzmueller CG, et al. The organization of intensive care unit physician services. Crit Care Med. 2007 Oct;35(10):2434-2435.

97 Stockwell DC, Slonim AD, Pollack MM. Physician team management affects goal achievement in the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:540-545.

98 Coleman N, Baker DP, Gallo J, et al. Critical outcomes: clinical and team performance across acute illness scenarios in emergency departments of critical access hospitals. J Hlthcare Qual. 2011. in press