chapter 11 Evaluating Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Examination of the Abdomen

When examining a child with acute abdominal pain, it often is necessary to decide whether the child has a problem requiring surgery (i.e., an acute abdomen). Surgical disorders often present with a shorter history, and the most common cause of an acute abdomen in children is appendicitis. Disorders presenting with acute abdomen are discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.

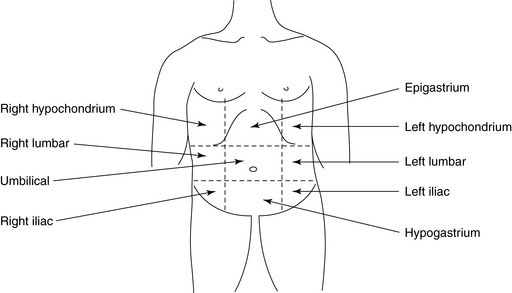

To describe the location of any abnormality, it helps to divide the abdomen into four quadrants with a horizontal line through the umbilicus and a vertical line from the xiphoid process to the symphysis pubis through the umbilicus. For infants and younger children with smaller abdomens, this division should suffice. For older children and adolescents, the abdomen can be divided into nine regions by including two additional vertical lines from the mid-clavicular area to the mid-inguinal point and two horizontal lines through the subcostal margins and the anterior iliac crests (Figure 11–1).

Palpation

The liver, spleen, and kidneys should always be palpated.

Liver

Always begin your palpation in the right iliac fossa so as not to miss the edge of a massively enlarged liver. The axis of your hand should be directed toward the right costal margin and at right angles to it. Rest your fingertips on the abdomen and gently depress them intermittently, without poking (Fig. 11–2). The child’s respiratory excursions will bring the liver down to make contact with the fingers (you don’t feel it; it feels you). One or both hands (one on top of another) may be used. Advance your fingers upward toward the costal margin in 1- to 2-cm increments.

Hepatomegaly can occur from many different causes, including:

Spleen

The spleen tip is palpable in about 10% of healthy children and often is palpable in newborns. In infants, the spleen enlarges downward toward the left lower quadrant, whereas in older children enlargement is toward the right lower quadrant. Palpation should begin in the right iliac fossa so as not to miss a very large spleen (Fig. 11–3). Be gentle, because an enlarged spleen could rupture if too much force is applied. Size should be recorded in centimeters below the left costal margin.

Kidneys

Kidneys are retroperitoneal and deep and are best palpated bimanually. With the child supine, place one hand in the renal (costovertebral) angle, beneath the twelfth rib and just lateral to the erector spinae (Fig. 11–4). Place your other hand anteriorly, just lateral to the rectus abdominis, in line with and parallel to the first hand. Ask the child to take a deep breath. Immediately at the end of inspiration, press your front hand firmly back against the other hand. A quick upward movement of the fingers of the hand in the renal angle is made (ballottement), and the kidney is trapped between the two hands. Unless the kidney is massively enlarged, successful renal palpation requires considerable experience. The percussion note over the kidney will be resonant because of overlying intestine, which helps differentiate it from the spleen or liver.

Rectal Examination

In older children, a rectal examination is best performed with the child in the left lateral position with the spine and knees fully flexed. Infants and younger children can be examined in a knee-chest position. The examination should be conducted systematically. Presence of stool in the underwear implies fecal incontinence, most likely from encopresis. Examine the perianal area for excoriations, skin tags, or fistulae. Sentinel skin tag(s) overlying a chronic anal fissure in older children are pathognomonic of Crohn’s disease (Fig. 11–5). The buttocks should be gently spread to look for any anal fissure. Acute anal fissures occur from passage of large, very hard stools. Digital rectal examination in such cases is painful and unnecessary. Acute anal fissures often are difficult to view because there is considerable spasm of the anal sphincters, and the child does not relax enough for good visualization. The diagnosis is best made by history.

Common Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Abdominal pain

Children and Adolescents

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical cause of acute abdominal pain. Appendicitis is a well-known mimic of other disorders and can escape the watchful eyes of even the most experienced clinician. Clinical features of acute appendicitis are described in Chapter 12.

Worrisome clinical features in the evaluation of children with chronic abdominal pain are listed in Box 11–1. The presence of any of these features should prompt a search for an organic cause.

Constipation

Pertinent questions to ask a child with chronic constipation are listed in Box 11–2. The earlier the constipation starts in life, the more the likelihood of finding an organic cause. For example, Hirschsprung disease should be suspected in a baby who has not passed meconium within 48 hours of birth. Approximately 90% of full-term babies pass their first meconium within 24 hours, and 99% do so within 48 hours of delivery. Hence the vast majority of cases are diagnosed in the newborn period. In older children, the stooling pattern in the neonatal period should be explored. Children with Hirschsprung disease may have recurrent vomiting and abdominal distension and may fail to thrive. The stools passed are often thin and ribbonlike, in contrast to the large-caliber stools seen in persons with functional fecal retention. Urinary symptoms may occur with chronic constipation by direct pressure of the distended colon on the bladder. However, the presence of urinary symptoms or gait disturbance also should alert one to a spinal cord problem. Obtain a detailed dietary history, especially milk intake. Children who drink unusually large amounts of whole milk may become quite constipated. Any drug that inhibits smooth muscle motility can cause constipation.

If the constipation becomes intractable despite adequate therapy, investigations for celiac disease, hypothyroidism, and hypercalcemia may be indicated. Usually, other clinical features point to these conditions (Fig. 11–6).

Vomiting and regurgitation

Infants and Toddlers

Pyloric stenosis presents around 4 to 6 weeks of age with progressive, nonbilious vomiting. The baby is hungry but cannot keep food down. Weight loss and dehydration are common. Physical examination may reveal a pyloric tumor on palpation, but locating it requires patience and considerable experience. Imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. Surgical causes of vomiting in infants are discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is arbitrarily termed chronic if it persists for more than 2 weeks. The vast majority of cases of chronic diarrhea are due to one of the disorders listed in Box 11–3.

In a child with diarrhea, important questions in the history should cover the topics listed in Box 11–4.

The gross appearance of the stool provides valuable information as to the likely etiology of diarrhea. Stools in patients with osmotic diarrhea are bulky and foul smelling. In patients with secretory diarrhea, they tend to be of high volume and watery. Stopping oral intake will improve osmotic diarrhea, but secretory diarrhea will continue until the stimulus (usually a toxin) is removed. In patients with inflammatory diarrhea, the stools are often small and contain mucus and blood. Perianal burning and rash suggest acidic stools from carbohydrate malabsorption. The presence of fresh blood in the stools implies colonic involvement, likely from infectious colitis or inflammatory bowel disease, and essentially rules out other conditions mentioned in Box 11–3.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Infants and Toddlers

Rectal bleeding in the first few months is most often from an anal fissure. A history of hard, painful stool makes the diagnosis more likely. The bright red blood streaks are typically on the surface of the stool. An acute anal fissure may be difficult to visualize due to spasm of the anal muscles. Passage of small amounts of bright red blood by way of the rectum is seen in persons with allergic colitis (i.e., milk protein sensitivity). Other clinical features, such as pain and diarrhea, may be absent. These infants are otherwise well and thriving. Other causes of rectal bleeding in infants include infectious colitis, necrotizing enterocolitis, intussusception, and Meckel diverticulum. The surgical causes of bleeding are discussed in Chapter 12.

Hyman P.E., Milla P.J., Benninga M.A, et al. Childhood functional GI disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519-1526.

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology. Hepatology and nutrition: Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:e1-e13.

Rasquin A., DiLorenzo C., Forbes D., et al. Childhood functional GI disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-1537.