Chapter 5 Ethnobotany and ethnopharmacy

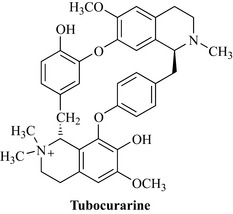

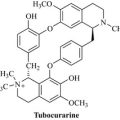

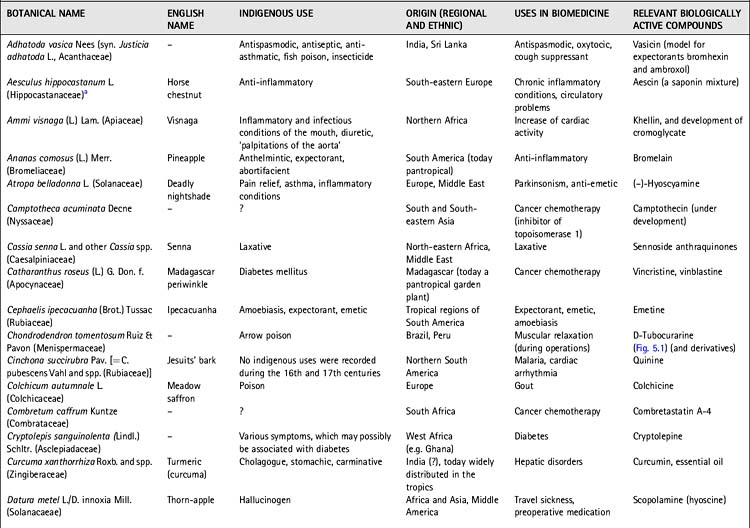

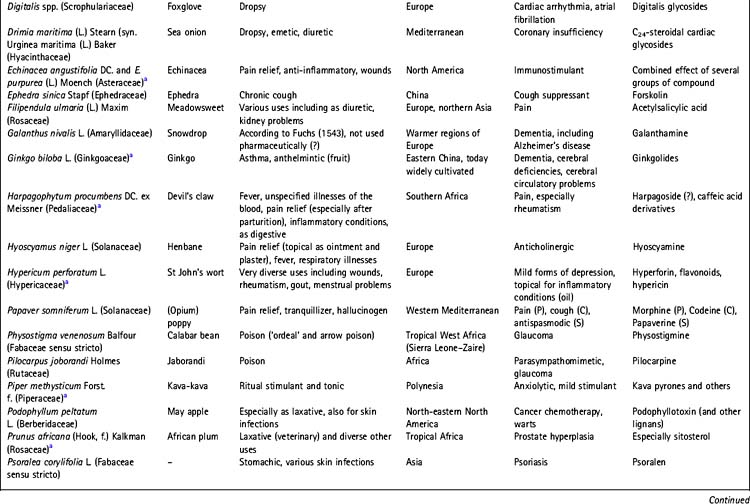

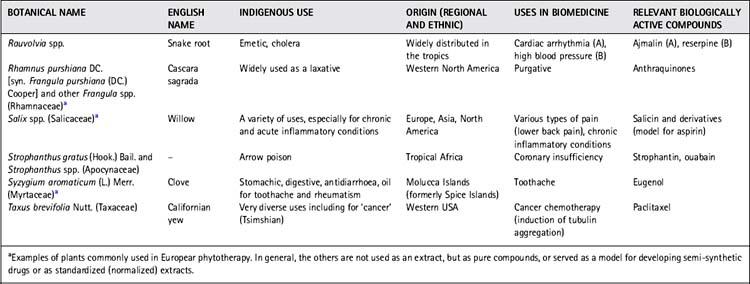

Many drugs that are commonly used today (e.g. aspirin, ephedrine, ergometrine, tubocurarine, digoxin, reserpine, atropine) came into use through the study of indigenous (including European) remedies – that is, through the bioscientific investigation of plants used by people throughout the world. Table 5.1 lists just a few of the many examples of drugs derived from plants. As can be seen, most plant-derived pharmaceuticals and phytomedicines currently in use were (and often still are) used by native people around the world. Accordingly, our information is derived from local knowledge as it was and is practised throughout the world, although European and Mediterranean traditions have had a particular impact on these developments. The historical development of this knowledge is discussed in Chapter 2. This chapter is devoted to traditions as old as, or older than the written records but which have been passed on orally from one generation to the next. Some of this information, however, may have not been documented in codices or studied scientifically until very recently.

Table 5.1 Botanical drugs used in indigenous medicine and of importance in the development of modern drugs

Ethnobotany

This broad definition is still used today, but modern ethnobotanists face a multitude of other tasks and challenges (see below). Medicinal plants have always been one of the main research interests of ethnobotany and the study of these resources has also made significant contributions to the theoretical development of the field (Berlin 1992); however, the more anthropologically oriented fields of research are beyond the scope of this introductory chapter.

Ethnopharmacology

Ethnopharmacology as a specifically designated field of research has had a relatively short history. The term was first used in 1967 in the title of a book on hallucinogens (see Efron et al 1970). The field is nowadays much more broadly defined.

The observation, identification, description and experimental investigation of the ingredients, and of the effects of the ingredients, and the effects of such indigenous drugs, is a truly interdisciplinary field of research which is very important in the study of traditional medicine. Ethnopharmacology is here defined as ‘the interdisciplinary scientific exploration of biologically active agents traditionally employed or observed by man’ (Bruhn & Holmstedt 1981: 405–406).

The story of curare

An interesting example of an early ethnopharmacological approach is provided by the study of the botanical origin of the arrow poison curare, its physiological effects and the compound responsible for these effects. Curare was used by certain, wild, tribes in South America for poisoning their arrows and many early explorers documented this usage. The historical aspects of the scientific investigation of curare by Bernard (1966) are outlined in Chapter 2, but the detailed descriptions made by Alexander von Humboldt in 1800, of the process used to prepare poisoned arrows in Esmeralda on the Orinoco River, are equally interesting. von Humboldt had met a group of native people who were celebrating their return from an expedition to gather the raw material for making the poison and he described the ‘chemical laboratory’ used to prepare the poison (Humboldt 1997:88, from the original text published 1800):

The botanical source of curare was eventually identified as the climbing vine Chondrodendron tomentosum Ruiz and Pavón; other species of the Menispermaceae (Curarea spp. and Abuta spp.) and Loganiaceae (Strychnos spp.) are also used in the production of curares of varying types (Bisset 1991). von Humboldt then eloquently described one of the classical problems of ethnopharmacology:

Ethnopharmacology and the convention on biological diversity (convention of RIO)

None of the studies discussed so far took the benefits for the providers (the states and their people) into account. This has changed in recent years. Ethnopharmacological and related research using the biological resources of a country are today based on agreements and permits, which in turn are based on international and bilateral treaties. The most important of these is the Convention of Rio or the Convention on Biological Diversity (see http://www.biodiv.org/chm/conv.htm), which looks in particular at the rights and responsibilities associated with biodiversity on an international level:

The basic principles of access are regulated in article 5:

The rights of indigenous peoples and other keepers of local knowledge are addressed in article 8j:

15.1. Recognizing the sovereign rights of States over their natural resources, the authority to determine access to genetic resources rests with the national governments and is subject to national legislation. 15.5. Access to genetic resources shall be subject to prior informed consent of the Contracting Party providing such resources, unless otherwise determined by that Party.

15.7. Each Contracting Party shall take legislative, administrative or policy measures…with the aim of sharing in a fair and equitable way the results of research and development and the benefits arising from the commercial and other utilization of genetic resources with the Contracting Party providing such resources. Such sharing shall be upon mutually agreed terms.

In the case of ethnopharmacological research, the needs and interests of the collaborating community become an essential part of the research, and in fact there is an inextricable link between cultural and biological diversity. This principle was first formulated at the 1st International Congress on Ethnobiology held in Belem (Brazil) in 1988. No generally agreed upon standards have so far been accepted, but the importance of obtaining the ‘prior informed consent’ of the informants has been stressed by numerous authors (e.g. Posey 2002).

Bioprospecting and ethnopharmacology

Studies dealing with medicinal and other useful plants and their bioactive compounds have used many concepts and methodologies. These are interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary studies, combining such diverse fields as anthropology, pharmacology, pharmacognosy or pharmaceutical biology, natural product chemistry, toxicology, clinical research, plant physiology and others. In order to analyse their strengths and weaknesses, and especially the outcomes of research, two different but closely related approaches can be distinguished: bioprospecting and ethnopharmacology (see Table 5.2).

| Ethnopharmacology | Bioprospecting |

|---|---|

| Overall goals | |

| (Herbal) drug development, especially for local uses | Drug discovery for the international market |

| Complex plant extracts (phytotherapy) | Pure natural products as drugs |

| Social importance of medicinal and other useful plants | – |

| Cultural meaning of resources and understanding of indigenous concepts about plant use and of the selection criteria for medicinal plants | – |

| Main disciplines involved | |

| Anthropology | – |

| Biology (ecology) | Biology including (very prominently) ecology |

| Pharmacology/molecular biology | Pharmacology and molecular biology |

| Pharmacognosy and phytochemistry | Phytochemistry |

| Number of samples collected | |

| Very few (up to several hundred) | As many as possible, preferably several thousand |

| Selected characteristics | |

| Detailed information on a small segment of the local flora (and fauna) | Limited information about many taxa |

| Database on ethnopharmaceutical uses of plants | Database on many taxa (including ecology) |

| Development of autochthonous resources (especially local plant gardens, small-scale production of herbal preparations) | Inventory (expanded herbaria) economically sustainable alternative use to destructive exploitation (e.g. logging) |

| Pharmacological study | |

| Preferably using low-throughput screening assays which allow a detailed understanding of the local or indigenous uses | The assay is not selected on the basis of local usage, instead high-throughput screening systems are used |

| Key problem | |

| Safety and efficacy of herbal preparations | Local agendas (rights) and compensation to access |

The importance of conserving such nature-derived products in the health care of the original keepers of such knowledge must be the main goal of truly interdisciplinary research. Ethnopharmacology may contribute to the development of new pharmaceutical products for the markets of the northern hemisphere, but this is only one of several targets. Truly multidisciplinary research on medicinal plants requires the inclusion of other methodologies from such fields as medical or pharmaceutical anthropology or sociology. Not only do we need a detailed understanding, incorporating social scientific and bioscientific methods, but we also need to support all means available of making better use of these products. It has been pointed out that the two approaches – ethnopharmacology and biodiversity prospecting – are not mutually exclusive and the two concepts as they are outlined here are rarely realized in such extreme forms. Instead, any discussion should specifically draw attention to particular strengths and roles of both approaches. In bioprospecting programmes, which are directed specifically towards infectious diseases, the use of ‘ethnobotanical’ information is very useful and promising (Lewis 2000). However, this is not necessarily the case in cancer chemotherapy, for example, where highly toxic plants are not used in traditional medicine because the dose cannot be controlled sufficiently well to ensure safety.

Examples of modern ethnopharmacological studies

A project focusing on the bioscientific study of indigenous uses of Hyptis verticillata (Lamiaceae) is a good example. This plant is prepared in different ways by the Lowland Mixe people of Oaxaca, Mexico, depending on the disease to be treated. For skin infections and inflammation, the plant is ground up with a little alcohol or the mashed leaves are applied directly to the affected part. However, for gastrointestinal problems, a tea is prepared using ‘a handful’ of fresh leaves (Heinrich 2001).

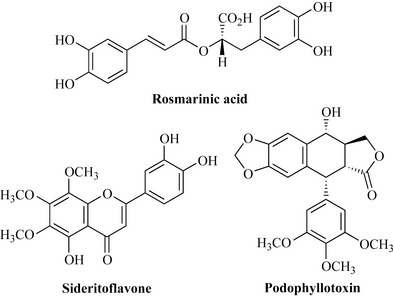

Phytochemical investigation using an inflammatory model as well as antibacterial activity led to the isolation of several lignans, rosmarinic acid and sideritoflavone (see Fig. 5.2). These compounds help to explain the rationale behind the indigenous uses. The lignans are known to have strong antibacterial activity, which was also corroborated in these studies, and both rosmarinic acid and sideritoflavone were shown to be active in anti-inflammatory models.

The second example is drawn from ethnobotanical fieldwork in Eastern Guatemala with a Mayan-speaking people, the Chorti. The Chorti use the fruit of Ocimum micranthum Willd. (Lamiaceae) in the treatment of infectious and inflammatory eye diseases (Kufer et al, unpublished). The fruits are approximately 1 mm in diameter and hard, and several of these are applied directly into the eye. At first glance this seems an unlikely remedy for eye problems, but the rationale behind it becomes evident when considering the morphological and chemical make-up. The fruits are covered with a mucilaginous layer containing complex polysaccharides which form a soft layer around the fruit if it is put into water (Heinrich 1992). This layer may well have a cleansing effect, and polysaccharides are known to be useful in the treatment of inflammatory conditions and bacterial or viral infections. Although there are no pharmacological data from experimental studies available to corroborate this use, information on the histochemical structure of the fruit makes it likely that the treatment has some scientific basis.

The above two examples demonstrate the relevance of ethnopharmacology in relation to the scientific study of indigenous medical products. However, ethnopharmacology, as the science bridging the gap between natural sciences and anthropology, should also look at symbolic and cognitive aspects. People may select plants because of their specific pharmacological properties, but also because of the symbolic power they may believe is in a plant. Understanding these aspects requires cognitive and symbolic analysis of field data. Another example from field studies with the Mixe in Mexico can be used. At the end of a course of medical treatment, the patient is sometimes given a petal of Argemone mexicana L. (known to the Mixe as San Pedro Agats, Papaveraceae). This plant is known to contain a large number of biologically active alkaloids, including protopine. However, the yellow petals are presumably used, not because they exert a pharmacological effect (at this dose) but because they symbolize the bread of the Last Supper according to Christian mythology. Thus they are a powerful symbol for the end of the healing process (for other examples of symbolic and empirical forms of plant use see Heinrich 2010).

The role of ethnopharmacology can be extended beyond that defined previously. It looks not only at empirical aspects of indigenous and popular plant use, but also at the cognitive foundations of this use. Only if these issues are to be included will it truly be a interdisciplinary field of research (Bruhn & Holmstedt 1981:406). The key tasks of pharmaceutical researchers in this interdisciplinary process will be to:

• study the pharmacological effects of the most widely used species (for selection criteria for the ethnopharmacologically most important taxa, see Heinrich et al 1998)

• further develop local ethnopharmacopoeias

• characterize the relevant constituents

• formulate improved (but relatively simple) galenical preparations.

This will result in a truly ethnopharmaceutical approach to medicinal plants which encompasses all subdisciplines of pharmacy and medicine. The value of integrating ethnobotanical with phytochemical and pharmacological studies has been clearly demonstrated. While, for example, the likelihood of developing new therapeutic agents for use in biomedicine is relatively low (although it is certainly much higher than with many other approaches), such studies confirm the therapeutic value and contribute to our general scientific knowledge about medicinal plants (Heinrich 2010).

Some plants have many side effects or are highly toxic. In an example from the Highlands of Mexico, Bah et al (1994) showed that a species popularly used there contains hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which pose potential health risks. Although this information is available to the scientific community, the general public may not be aware of these risks. Such data must be summarized appropriately and made available to local people in regions where the plants are used. It is now essential to develop partnerships with institutions capable of translating these findings into an effective strategy.

Bah M., Bye R., Pereda-Miranda R. Hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids in the Mexican medicinal plant Packera candidissima (Asteraceae: Senecioneae). J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1994;43:19-30.

Berlin B. Ethnobiological classification. Principles of categorization of plants and animals in traditional societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1992.

Bernard C. Physiologische Untersuchungen über einige amerikanische Gifte. Das Curare. In: Bernard C., Mani N., editors. Ausgewählte physiologische Schriften. Bern: Huber Verlag; 1966:84-133. [frz. orig. 1864]

Bisset N.G. One man’s poison, another man’s medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1991;32:71-81.

Bruhn J.G., Holmstedt B. Ethnopharmacology: objectives, principles and perspectives. In: Beal J.L., Reinhard E., editors. Natural products as medicinal agents. Stuttgart: Hippokrates Verlag; 1981:405-430.

Efron D., Farber S.M., Holmstedt B. Ethnopharmacologic search for psychoactive drugs. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1970. Public Health Service Publications no. 1645

Heinrich M. Economic botany of American Labiatae. In: Harley R.M., Reynolds T., editors. Advances in Labiatae Science. Kew: Royal Botanical Gardens; 1992:475-488.

Heinrich M. Ethnobotanik und Ethnopharmakologie. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2001. Eine Einführung

Heinrich M. Ethnopharmacology and drug development. In: Mander L., Lui H.W., editors. Comprehensive natural products II. Chemistry and biology, vol. 3. Oxford: Elsevier; 2010:351-381.

Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., et al. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med.. 1998;47:1863-1875.

Lewis W. Ethnopharmacology and the search for new therapeutics. In: Minnis P.E., Elisens W.J., editors. Biodiversity and native America. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

Posey D.A. Kayapó ethnoecology and culture. In: Plenderleith K., editor. Studies in environmental anthropology, vol 6. London: Routledge; 2002.

Brett J., Heinrich M. Culture perception and the environment. Journal of Applied Botany. 1998;72:67-69.

Cotton C.M. Ethnobotany. Chichester: Wiley; 1997.

Etkin N.L. Ethnopharmacology: biobehavioral approaches in the anthropological study of indigenous medicines. Ann. Rev. Anthropol.. 1985;17:23-42.

Etkin N.L., Harris D.R., Prendergast H.D.V., et al. Plants for food and medicine. Kew: Royal Botanical Gardens; 1998.

Heinrich M. Herbal and symbolic medicines of the Lowland Mixe (Oaxaca, Mexico): disease concepts, healers’ roles, and plant use. Anthropos. 1994;89:73-83.

Heinrich M., Robles M., West J.E., et al. Ethnopharmacology of Mexican Asteraceae (Compositae). Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol.. 1998;38:539-565.

Moerman D.E. Native American ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press; 1998.

Neuwinger D. African traditional medicines. Stuttgart: Medpharm; 2000.

Okpako D.T. Principles of pharmacology: a tropical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

Okpako D.T. Traditional African medicine: theory and pharmacology explored. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.. 1999;20:482-485.

Schultes R.E. The role of the ethnobotanist in the search for new medicinal plants. Lloydia. 1962;25:257-266.

Schultes R.E. Richard Spruce: an early ethnobotanist and explorer of the Northwest Amazon and Northern Andes. J. Ethnobiol.. 1983;3:139-147.

Schultes R.E., Nemry von Thenen, de Jaramillo-Arango M.J. The journals of Hipólito Ruiz: Spanish botanist in Peru and Chile 1777–1788. Portland, OR: Timber Press; 1998.

Schultes R.E., Raffauf R. The healing forest. Dioscorides Press, Portland, OR: Medicinal and toxic plants of the Northwest Amazonia; 1990.

Sofowara A. African medicinal plants: proceedings of a conference. Nigeria: University of Ife Press; 1979.

Thomas O.O. Perspectives on ethno-phytotherapy of Yoruba medicinal medicinal plants and preparations. Fitoterapia. 1989;60:49-60.

von Humboldt A. Die Forschungsreise in den Tropen Amerikas. Studienausgabe Bd 2, Teilband 3. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft; 1997. (Hrsg. H Beck)