5 Ethical Issues in Critical Care

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• understand the diversity and complexities of ethical issues involving critical care practice

• understand key ethical principles and how to apply them in everyday practice as a critical care registered nurse

• be aware of the availability and access to additional resource material that may inform and support complex ethical decisions in clinical practice

• discuss the ethical implications of the organ donation for transplantation decision-making process

• understand consent and guardianship issues in critical care

• describe the ethical conduct of human research, in particular issues of patient risk, protection and privacy, and how to apply ethical principles within research practice.

Introduction

Nurses are expected to practise in an ethical manner, through the demonstration of a range of ethical competencies articulated by registering bodies and the relevant codes of ethics (see Boxes 5.1 and 5.2). It is important that nurses develop a ‘moral competence’ so that they are able to contribute to discussion and implementation of issues concerning ethics and human rights in the workplace.1 Moral competence and ethical action is the ability to recognise that an ethical issue exists in a given clinical situation, knowing when to take ethical action if and when required, and a personal commitment to achieve moral outcomes.2 This diverse understanding of ethics is paramount to critical care nurses (as part of the critical care team), whose patient cohort is a particularly vulnerable one. Critical care nurses are encouraged to participate in discussion and educational opportunities regarding ethics in order to provide clarity in relation to fulfilment of their moral obligations. The need to support critical care nurses, by mentoring for example, is very important in terms of developing moral knowledge and competence in the critical care context.3

Box 5.1

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council Code of Ethics for Nurses in Australia, June 200261

Value statements

1. Nurses respect individual’s needs, values, culture and vulnerability in the provision of nursing care.

2. Nurses accept the rights of individuals to make informed choices in relation to their care.

3. Nurses promote and uphold the provision of quality nursing care for all people.

4. Nurses hold in confidence any information obtained in a professional capacity, use professional judgement where there is a need to share information for the therapeutic benefit and safety of a person, and ensure that privacy is safeguarded.

5. Nurses fulfil the accountability and responsibility inherent in their roles.

6. Nurses value environmental ethics and a social, economic and ecologically sustainable environment that promotes health and wellbeing.

Principles, Rights and the Link with Law

The Distinction between Ethics and Morality

Ethics involve principles and rules that guide and justify conduct. Personal ethics may be described as a personal set of moral values that an individual chooses to live by, whereas professional ethics refer to agreed standards and behaviours expected of members of a particular professional group.2 Bioethics is a broad subject that is concerned with the moral issues raised by biological science developments, including clinical practice.

Although some nurses draw a distinction between ethics and morality, there is no philosophical difference between the two terms, and attempting to make a distinction can cause confusion.4 Difficulties arise in ethical decision making where no consensus has developed or where all the alternatives in a given situation have specific drawbacks. These types of situations are referred to as ‘ethical dilemmas’. Dilemmas are different from problems, because problems have potential solutions.5

Ethical Principles

Autonomy

Individuals should be treated as autonomous agents; and individuals with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. An autonomous person is an individual capable of deliberation and action about personal goals. To respect autonomy is to give weight to autonomous persons’ considered opinions and choices, while refraining from obstructing their actions unless these are clearly detrimental to others or themselves. To show lack of respect for an autonomous agent, or to withhold information necessary to make a considered judgement, when there are no compelling reasons to do so, is to repudiate that person’s judgements. To deny a competent individual autonomy is to treat that person paternalistically. However, some persons are in need of extensive protection, depending on the risk of harm and likely benefit of protecting them, and in these cases paternalism may be considered justifiable.6,7

Nurses are autonomous moral agents, and at times may adopt a personal moral stance that makes participation in certain interventions or procedures morally unacceptable (see the Conscientious objection section later in this chapter).

Beneficence and Non-maleficence

The principle of beneficence requires that nurses act in ways that promote the wellbeing of another person; this incorporates the two actions of doing no harm, and maximising possible benefits while minimising possible harms (non-maleficence).8 It also encompasses acts of kindness that go beyond obligation. In practice this means that although the caregiver’s treatment is aimed to ‘do no harm’, there may be times where to ‘maximise benefits’ for positive health outcomes it is considered ethically justifiable that the patient be exposed to a ‘higher risk of harm’ (albeit ‘minimised’ by the caregiver as much as possible). For example, in the coronary care unit (CCU) a patient may require a central venous catheter (CVC) to optimise fluid and drug therapy, but this is not without its own inherent risks (e.g. infection, pneumothorax on insertion). Evidence-based protocols exist for caregivers/nurses for both the safe insertion of a CVC and subsequent care, so as to minimise possible harms to the patient.

Justice

Justice may be defined as fair, equitable and appropriate treatment in light of what is due or owed to an individual. The fair, equitable and appropriate distribution of health care, determined by justified rules or ‘norms’, is termed distributive justice.6 There are various well-regarded theories of justice. In health care, egalitarian theories generally propose that people be provided with an equal distribution of particular goods or services. However, it is usually recognised that justice does not always require equal sharing of all possible social benefits. In situations where there is not enough of a resource to be equally distributed, often guidelines or policies (e.g. ICU admission policies) may be developed in order to be as fair and equitable as possible.

Conditions of scarcity and competition result in the predominant problems associated with distributive justice. For example, a shortage of intensive care beds may result in critically ill patients having to ‘compete’, in some way, for access to the ICU. Considerable debate exists regarding ICU access/admission criteria, that may vary across institutions. Resource limitations can potentially be seen to negatively affect distributive justice if decisions about access are influenced by economic factors, as distinct from clinical need.9

Ethics and the Law

Ethics are quite distinct from legal law, although these do overlap in important ways. Moral rightness or wrongness may be quite distinct from legal rightness or wrongness, and although ethical decision making will always require consideration of the law, there may be disagreement about the morality of some law. Much ethically-desirable nursing practice, such as confidentiality, respect for persons and consent, is also legally required.4,10

In Australia, there are three broad sources of law. These are:

• Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA);

• Medical Treatment Act 1988 (Vic.);

One example of how statute law is applied in practice regards consent for life-sustaining measures; the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA)11 states that:

It should be noted that each Australian state and territory has differences in its Acts, which can cause confusion. The New Zealand Bill of Rights and the Health Act 1956 are currently under revision in New Zealand.12,13 These documents can be accessed via the New Zealand Ministry of Health (www.hon.govt.nz).

Patients’ Rights

Patients’ rights are a subcategory of human rights. ‘Statements of patients’ rights’ relate to particular moral interests that a person might have in healthcare contexts, and hence require special protection when a person assumes the role of a patient.4 Institutional ‘position statements’ or ‘policies’ are useful to remind patients, laypersons and health professionals that patients do have entitlements and special interests that need to be respected. These statements also emphasise to healthcare professionals that their relationships with patients are constrained ethically and are bound by certain associated duties.4 In addition, the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses has published a Position Statement on the rights of the critically ill patient (see Appendix A3).

Nursing codes of ethics incorporate such an understanding of patient’s rights. For example, codes relevant to nurses have been developed by the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (2002)61 and the International Council of Nurses (2002)14 (see Box 5.1). In addition, the Nursing Council of New Zealand has published a Code of Conduct for Nursing that incorporates ethical principles (2004) (Box 5.2).15 These codes outline the generic obligation of nurses to accept the rights of individuals, and to respect individuals’ needs, values, culture and vulnerability in the provision of nursing care. The New Zealand Code particularly notes that nurses need to practise in a manner that is ‘culturally safe’ and that they should practise in compliance with the Treaty of Waitangi. (See Chapter 8 for further details on cultural aspects of care.) Furthermore, the codes acknowledge that nurses accept the rights of individuals to make informed choices about their treatment and care.

Consent

In principle, any procedure that involves intentional contact by a healthcare practitioner with the body of a patient is considered an invasion of the patient’s bodily integrity, and as such requires the patient’s consent. A healthcare practitioner must not assume that a patient provides a valid consent on the basis that the individual has been admitted to a hospital.16 All treating staff (nurses, doctors, allied health etc) are required to facilitate discussions about diagnosis, treatment options and care with the patient, to enable the patient to provide informed consent.17 When specific treatment is to be undertaken by a medical practitioner, the responsibility for obtaining consent rests with the medical practitioner; this responsibility may not be delegated to a nurse.16

Patients have the right, as autonomous individuals, to discuss any concerns or raise questions, at any time, with staff. Hospitals should provide detailed patient admission information, including information regarding ‘patients’ rights and responsibilities’, that usually include a broad explanation of the consent process within that institution. In many countries there is no distinction between the obligation to obtain valid consent from the patient and the overall duty of care that a practitioner has in providing treatment to a patient. Obtaining consent is part of the overall duty of care.11

In recent decades, research in the biomedical sciences has been increasingly located in settings outside of the global north. Much of this research arises out of transnational collaborations made up of sponsors in high income countries (pharmaceutical industries, aid agencies, charitable trusts) and researchers and research subjects in low- to middle-income ones. Research may well be carried out in populations rendered vulnerable because of their low levels of education and literacy, poverty and limited access to health care, and limited research governance. The protections that medical and research ethics offer in these contexts tend to be modelled on a western tradition in which individual informed consent is paramount and are usually phrased in legal and technical requirements. When science travels, so does its ethics. Yet, when cast against a wider backdrop of global health, economic inequalities and cultural diversity, such models often prove limited in effect and inadequate in their scope.2,3 Attempts to address both of these concerns have generated a wide range of ‘capacity-building’ initiatives in bioethics in developing and transitional countries. Organisations such as the Global Forum for Bioethics in Research, the Forum for Ethical Review Committees in the Asia Pacific Region and the World Health Organization have sought to improve oversight of research projects, refine regulation and guidance, address cultural variation, educate the public about research and strengthen ethical review committee structures according to internationally acknowledged ‘benchmarks’.4,5

In order to provide safe patient care, clear internal systems and processes are required within critical care areas, as with any other healthcare service provision. Critical care nurses need to be aware of the relevant policies and procedures to have an understanding of their individual obligations and responsibilities. Primarily, it is the treating medical officer who is legally regarded as the only person able to inform the patient about any material risks associated with a clinical therapy or intervention.18

An understanding of the principle of consent is necessary for nurses practising in critical care. Because of the vulnerable nature of the critically ill individual, direct informed consent is often difficult, and surrogate consent may be the only option, particularly in an emergency. Consent may relate to healthcare treatment, participation in human research and/or use and disclosure of personal health information. Each of these types of consent has differing requirements.19

Consent to treatment

A competent individual has the right to decline or accept healthcare treatment. This right is enshrined in common law in Australia (with state to state differences), and in the Code of Health and Disability Consumers’ Rights in New Zealand (1996).13,20 It is the cornerstone of the legal administration of healthcare treatment. With the introduction in the UK of the Human Rights Act21 there is increasing public awareness of individual rights, and in the medical setting people are encouraged to participate actively in decisions regarding their care. Doctors daily make judgements regarding their patients’ competency to consent to medical investigation and treatment, and in today’s litigious climate they must face the possibility that, from time to time, these decisions will be examined critically in a court of law. Capacity fluctuates with both time and the complexity of the decision being made; thus, sound decisions require careful assessment of individual patients.

Accounts of informed consent in medical ethics claim that it is valuable because it supports individual autonomy yet there are distinct conceptions of individual autonomy, and their ethical importance varies. Consent provides assurance that patients and others are neither deceived nor coerced. Some believe that the present debates about the relative importance of generic and specific consent (particularly in the use of human tissues for research and in secondary studies) do not address this issue squarely, believing that since the point of consent procedures is to limit deception and coercion, they should be designed to give patients and others control over the amount of information they receive and the opportunity to rescind consent already given.22 There is a professional, legal and moral consensus about the clinical duty to obtain informed consent. Patients have cognitive and emotional limitations in understanding clinical information. Such problems pose practical problems for successfully obtaining informed consent. Better communication skills among clinicians and more effective educational resources are required to solve these problems. Social and economic inequalities are important variables in understanding the practical difficulties in obtaining informed consent. Shared decision making within clinical care reveals a pronounced tension between three competing factors: (1) Paternalistic conservatism about disclosure of information to patients has been eroded by moral arguments now largely accepted by the medical profession; (2) While many patients may wish to be given information about available treatment options, many also appear to be cognitively and emotionally ill equipped to understand and retain it; and (3) Even when patients do understand information about potential treatment options, they do not necessarily wish to make such choices themselves, preferring to leave final decisions in the hands of their clinicians.23

Consent is considered valid when the following criteria are fulfilled; consent must:

• be informed (the patient must understand the broad nature and effects of the proposed intervention and the material risks it entails)

For incompetent individuals, the situation is less clear and varies between jurisdictions.

To be competent, an individual must:

• be able to comprehend and retain information

• believe it (i.e. they must not be impervious to reason, divorced from reality or incapable of judgement after reflection)

• be able to weigh that information up (i.e. consider the effects of having or not having the treatment)

In an emergency, healthcare treatment may be provided without the consent of any person, although ‘emergency’ has not routinely been formally defined. It should also be noted that nurses must seek consent for all procedures that involve ‘doing something’ to a patient (e.g. administering an injection), and should be wary of relying on ‘implied’ consent. Seeking consent in this type of everyday situation is less formal than obtaining consent for a surgical intervention, although it still represents ethically (and legally) prudent practice. Consent should never be implied, despite the fact that the patient is in a critical care area.17 Obtaining consent generally involves explaining the procedure and seeking affirmation from the patient (or guardian/family), ensuring that there is understanding and agreement to the treatment. This principle is clearly articulated by the General Medical Council in the UK with the following statement:

Successful relationships between doctors and patients depend on trust. To establish that trust you must respect patients’ autonomy – their right to decide whether or not to undergo any medical intervention … [They] must be given sufficient information, in a way that they can understand, in order to enable them to make informed decisions about their care.24

In many countries, if patients believe that clinicians have abused their right to make informed choices about their care, they can pursue a remedy in the civil courts for having been deliberately touched without their consent (battery) or for having received insufficient information about risks (negligence). To avoid the accusation of battery, clinicians need to make clear what they are proposing to do and why ‘in broad terms’. With respect to negligence, the amount of information about risks required is that deemed by the court to be ‘reasonable’ in light of the choices that patients confront.25

If a person is assessed as not being competent, consent must be sought from someone who has lawful authority to consent on his or her behalf. If the courts have appointed a person to be a guardian for an incompetent individual, then the guardian can provide consent on behalf of that individual. However, even for formally-appointed guardians, certain procedures are not allowed and the consent of a guardianship authority is required. If there is no guardianship order then, strictly speaking, consents for healthcare treatment may be given only by the guardianship authority. Some states have legislated to allow this authority to be delegated to a ‘person responsible’ or ‘statutory health authority’ without prior formal appointment. This person would usually be a spouse, close relative or unpaid carer of the incompetent individual. As with formally appointed guardians, the powers of a ‘person responsible’ are limited by statute.19

Consent to research involving humans

Consent in human research is guided by a variety of different documents. In Australia this predominantly includes the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007);8 while in New Zealand it is by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRCNZ), Guidelines on Ethics in Health Research and the HRCNZ Operational Standard for Ethics Committee (OS).26,27 In the UK guidance is provided by the General Medical Council.24 In the US there are required elements of written Institutional Review Board (IRB) procedures under Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations for the protection of human subjects and relevant Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) Department of Health and Human Services ‘guidance’ regarding each required element.

Although the specific detail varies between organisations and jurisdictions, in general ‘consent to medical research documentation’ should include the following:19

• A statement that the study involves research

• An explanation of the purposes of the research

• The expected duration of the subject’s participation

• A description of the procedures to be followed

• Identification of any procedures which are experimental

• A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject

• A description of any benefits to the subject or to others which may reasonably be expected from the research

• A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject

• A statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained

• For research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any compensation, and an explanation as to whether any medical treatments are available, if injury occurs and, if so, what they consist of, or where further information may be obtained.

• An explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research and research subjects’ rights, and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury to the subject

• A statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits, to which the subject is otherwise entitled.

Consent to conduct research involving unconscious individuals (incompetent adults) in critical care is one of the situations not comprehensively covered in most legislation (see also Ethics in research later in this chapter).

Application of Ethical Principles in the Care of the Critically Ill

Critical care nurses should maintain awareness of the ethical principles that apply to their clinical practice. The integration of ethical principles in everyday work practice requires concordance with care delivery and ethical principles. There is a risk that nurses may become socialised into a prevailing culture and associated thought processes, such as the particular work group on their shift, the unit where they are based, or the institution in which they are employed. Depending on the prevalent culture at any one of these levels, nursing practice may be highly ethical or less ethically justifiable. The ‘group think’ approach of ‘That’s how we’ve always done it’ requires critical reflection on what is the ethical or ‘right thing to do’.28 Clinical audits and other dedicated review systems and processes are useful platforms for ethical discussion and debate between critical care colleagues.

End-of-Life Decision Making

With advances in technology in health care, it is possible more than ever before to restore, sustain and prolong life with the use of complex technology and associated therapies, such as mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal oxygenation, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation devices, haemodialysis and organ transplantation. In addition, new medication treatment options contribute significant promises of added benefits, and fewer side effects, and are heralded by drug companies and journals across the world. Combinations of these therapies in critical care units are part of everyday management of critically ill patients. While technology is capable of maintaining some of the vital functions of the body, it may be less able to provide a cure. Managing the critically ill patient in many cases represents a provision of supportive, rather than curative, therapies.29

A common ethical dilemma found in critical care is related to the opposing positions of ‘maintaining life at all costs’ and ‘relieving suffering associated with prolonging life ineffectively’. Patients that would probably have previously died can now be maintained for prolonged periods on life support systems, even if there is little or no chance of regaining a reasonable quality of life. Assessment of their ‘post-critical illness’ quality of life is complex, emotive and forms the basis of significant debate, compounded by the nuances of each individual patient’s case. Hence, decisions regarding withdrawal and withholding of life support treatment(s) are not made without substantial consideration by the critical care team.30

Withdrawing/Withholding Treatment

The incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from critically ill patients has increased to the extent that these practices now precede over half the deaths in many ICUs,31 although the incidence in other critical care areas has not been reported. Although there is a legal and moral presumption in favour of preserving life, avoiding death should not always be the pre-eminent goal.32 The withholding or withdrawal of life support is considered ethically acceptable and clinically desirable if it reduces unnecessary patient suffering in patients whose prognosis is considered hopeless (often referred to as ‘futile’) and if it complies with the patient’s previously stated preferences. Life support includes the provision of any or all of ventilatory support, inotropic support for the cardiovascular system and haemodialysis, to critically ill patients. Withholding/withdrawal of life support are processes by which healthcare therapy or interventions either are not given or are forgone, with the understanding that the patient will most probably die from the underlying disease.33

In Australia, when active treatment is withdrawn or withheld, legally the same principles apply. The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) recommends an ‘alternative care plan’ (comfort care) be implemented with a focus on dignity and comfort. All discussions should be recorded in the medical records including the basis for the decision, who has been involved and the specifics of treatment(s) being withheld or withdrawn.34 There are marked differences in the ‘foregoing of life-sustaining treatments’ that occur between countries and in the patient level of care variation even within the same country. What may be adopted legally and ethically or morally in one country may not be acceptable in another. The withholding and withdrawing of therapies is considered passive euthanasia and is legal and accepted practice in terminally-ill ICU patients in most of Europe, however in parts of Europe, life-sustaining treatments are withheld but not withdrawn as the withdrawal of therapies leading to death is considered illegal and unethical. In the Netherlands and Belgium, active life ending procedures are permitted and performed with the specific intent of causing or hastening a patient’s death. In the US35–37 and Europe38 the majority of doctors have withheld or withdrawn life-sustaining treatments.

The majority of the community and doctors favour active life-ending procedures for terminally-ill patients.39,40 In the Ethicatt study, questionnaires on end of life decision-making were given to 1899 doctors, nurses, patients who were in ICUs and family members of the patients in six European countries. Less than 10% of doctors and nurses would like their life prolonged by all available means, compared to 40% of patients and 32% of families. When asked where they would rather be if they had a terminal illness with only a short time to live, more doctors and nurses preferred being home or in a hospice and more patients and families preferred being in an ICU. Differences in responses were based on respondent’s country.39,40

Diverse cultural, religious, philosophical, legal and professional attitudes lead to great difference in attitudes and practices. Observational studies demonstrate that North American health care workers consult families more often than do European workers,39,41 and some seriously ill patients wish to participate in end of life decisions whilst others do not.42

In most cases where there is doubt about the efficacy and appropriateness of a life-sustaining treatment, it may be considered preferable to commence treatment, with an option to review and cease treatment in particular circumstances after broad consultation. Inconsistency exists in decision making about when and how to withdraw life-sustaining treatment, and the level of communication among staff and family.9 Documented guidelines for cessation of treatment are not necessarily common in clinical practice, with disparate opinion a recognised concern in some cases. Dilemmas arise when there are disparate views within the team as to what constitutes ‘futility’ and with associated decisions regarding the next step or steps when a patient’s outlook is at its most grave. In a UK study that attempted to draft cessation of treatment guidelines, nursing staff were concerned over legality, morality, ethics and their own professional accountability. Medical decisions to withdraw treatment were shown to vary between medical staff and among patients with similar pathologies.43

Because ethical positions are fundamentally based on an individual’s own beliefs and ethical perspective, it may be difficult to gain a consensus view on a complex clinical situation, such as withdrawal of treatment. While it is essential that all members of the critical care team be able to contribute and be heard, the final decision (and ultimately legal accountability in Australia and New Zealand for the act of withdrawal of therapy) rests with the treating medical officer. However, the decision-making process certainly must involve broad, detailed and documented consultation with family and team members. If there is stated objection from a family member, especially if the person has medical power of attorney (or equivalent), the doctor must take this into consideration and respect the rights of any patient’s legal representative. In that event, it is likely that withdrawal of treatment will not occur until concordance is reached. (This is different in the case of a person who is legally declared brain dead; see Brain death section.)34

In the Ethicus study of 4248 patients who died or had limitations of treatments in 37 ICUs in 17 European countries, life support was limited in 73% of patients. Both withholding and withdrawing of life support was practised by the majority of European intensivists while active life ending procedures despite occurring in a few cases remained rare.38 The ethics of withdrawal of treatment are discussed in detail in the ANZICS Statement on Withholding and Withdrawing Treatment.34 The NHMRC publication entitled Organ and Tissue Donation, After Death, for Transplantation: Guidelines for Ethical Practice for Health Professionals provides further discussion of the ethics of organ and tissue donation.44

Decision-Making Principles

End-of-life decision making is usually very difficult and traumatic. Because of this difficulty, there is sometimes a lack of consistency and objectivity in the initiation, continuation and withdrawal of life-supporting treatment in a critical care setting.30 Traditionally, a paternalistic approach to decision making has dominated, but this stance continues to be challenged as greater recognition is given to the personal autonomy of individual patients.9

Decision making in the critical care setting is conducted within, and is shaped by, a particular sociological context. In any given decision-making situation, the participants hold different presumptions about their roles in the process, different frames of reference based on different levels of knowledge, and different amounts of relevant experience.45 Nurses, for example, may conform to the dominant culture in order to create opportunities to participate in decision making, and thereby may conform to the values and norms of medicine. Although the nursing role in critical care is pivotal to implementing clinical decisions, it is sometimes unacknowledged and devalued. Nurses appear at times unable to influence the decision-making process.46

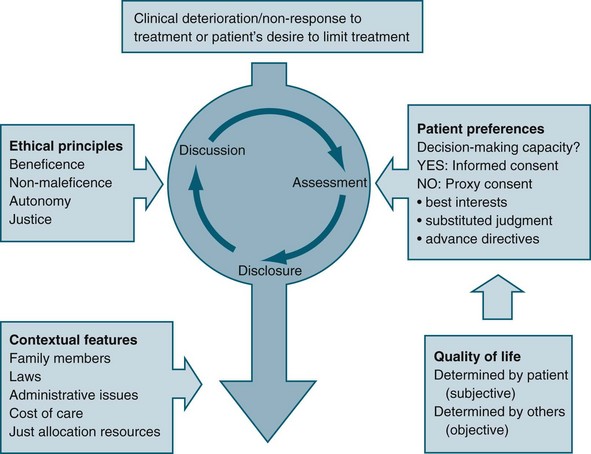

Some international literature reflects the different ethical reasoning and decision-making frameworks extant between medical staff and nurses. In general, nurses focus on aspects such as patient dignity, comfort and respect for patients’ wishes, while medical staff tend to focus on patients’ rights, justice and quality of life.47 Involvement of the patient (where possible) and family in decision making is an important aspect of matching the care provided with preferences, expectations, values and circumstances (see Figure 5.1).48

Quality of Life

Despite the importance placed on quality of life in terms of its influence in the decision-making process, it is difficult to articulate a common understanding of the concept. Quality of life is often used as a means of justifying a particular decision about treatment that results in either cessation of life or continued life-sustaining treatment, and it tends to be expressed as if a shared understanding exists.4

Often, quality of life is considered to consist of both subjective and objective components, based on the understanding that a person’s wellbeing is partly related to both aspects; therefore, in any overall account of the quality of life of a person, consideration is given to both independent needs and personal preferences.9 Subjective components refer to the experience of personal satisfaction or happiness, or the attainment of personal informed desires or preferences. Conversely, objective components refer to factors outside the individual, and tend to focus on the notion of ‘need’ rather than desires (e.g. the level to which basic needs are met, such as avoiding harm, and adequate nutrition and shelter).

Best Interests Principle

The best interests principle relies on the decision makers possessing and articulating an understanding or account of quality of life that is relevant to the patient in question, particularly in making end-of-life decisions. Although assumptions are commonly made that a shared understanding of the concept of quality of life exists, it may be that the patient’s perspective on what gives his or her life meaning is quite different from that of other people. In addition, individual preferences may change over time. For example, John may have stated in the past that he would never want to live should he be confined to a wheelchair; however, after an accident has rendered him a quadriplegic his preference may well be different. Ethical justification of the best interests principle therefore requires a relevant and current understanding of what quality of life means to the particular patient of concern.49

Patient Advocacy

Enduring guardians can potentially make a wider range of decisions than a medical agent, but an enduring guardian can make decisions only once a person is considered to be unable to make his/her own decisions. Acts such as the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA) exist to facilitate choice in healthcare treatment that individuals may wish to have or refuse when they are unable to make their wishes known because of an illness.11

Substituted Judgement Principle

A substituted judgement is where an ‘appropriate surrogate attempts to determine what the patient would have wanted in his/her present circumstances’.50 The person making the decision should therefore attempt to utilise the values and preferences of the patient, implying that the proxy decision maker would need an in-depth knowledge of the patient’s values to do so. Making a substituted judgement is relatively informal, in the sense that the patient usually has not formally appointed the proxy decision maker. Rather, the role of proxy tends to be assumed on the basis of an existing relationship between proxy and patient. Difficulties related to this principle include that making an accurate substituted judgement is very difficult, and that the proxy might not be the most appropriate person to have taken on the role.51

Advance Directives

For individuals wanting to document their preferences regarding future healthcare decisions with the onset of incompetence, there are ‘anticipatory direction’ and ‘advance directive’ forms available. Advance directives can be signed only by a competent person (before the onset of incompetence), and can be either instructional (e.g. a living will) or proxy (the appointment of a person(s) with enduring power of attorney to act as surrogate decision maker), or some combination of both. Advance directives can therefore inform health professionals how decisions are to be made, in addition to who is to make them. New Zealand and most states of Australia have an Act that allows for the appointment of a person to hold enduring power of attorney.52 It is found in the literature that most individuals do not want to write advanced directives and are hesitant to document their end of life care desires. Advance directives were created in response to increasing medical technology.53,54

An advance health care directive, also known as a living will, personal directive, advance directive or advance decision, are instructions given by individuals specifying what actions should be taken for their health in the event that they are no longer able to make decisions due to illness or incapacity, and appoints a person to make such decisions on their behalf. A living will is one form of advance directive, leaving instructions for treatment. Another form authorises a specific type of power of attorney or health care proxy, where someone is appointed by the individual to make decisions on their behalf when they are incapacitated. People may also have a combination of both. One example of a combination document is the Five Wishes advance directive in the US, created by the non-profit organisation Aging with Dignity.55 Although not legal documents, ‘good palliative care plans’ are used in some jurisdictions as a record of a discussion between the patient, family members and a doctor about palliative care or active treatment. These are useful records to provide clarity when treatment options require full and frank discussion and consideration, particularly regarding complex, critically ill patients (see Palliative care below).

Medical Futility

The concept of futility may be used by critical care doctors and nurses as a rationale for why treatment, including life-saving or sustaining treatment, is not considered to be in the patient’s best interests. At times, the concept of futility may be used inappropriately, and therefore unethically, for example if used to coerce relatives into agreeing to cease the patient’s treatment.56

Futility is a concept that has widespread use in healthcare ethics guidelines for the cessation of treatment, particularly with reference to ‘do-not-resuscitate’ orders and the withdrawal of lifesaving or sustaining treatment. Treatment is considered futile if it merely preserves permanent unconsciousness or cannot end dependence on intensive health care.50 Futility is used to cover both cases of predicted impossibility of the success of treatment (‘physiological’ futility) and cases in which there are competing interpretations of probabilities and value judgements, such as a balance of probable benefits and burdens.6

Physiological futility is also commonly defined as ‘useless treatment’; when clinicians conclude (through personal experience, experience shared with colleagues, or consideration of reported empirical data) that in the past 100 cases a healthcare treatment has had no desired effect.57 This particular definition is purported to defend against doctors being pressured into pursuing extreme and absurd interventions as a result of not being able to claim categorically that a particular treatment will be useless. The proposal is justified by appealing to the commonly used statistical evaluation employed in clinical trials (P = 0.01). A physiologically futile treatment may be, for example, cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the setting where the patient has a ruptured left ventricle.

There is no definition of futility in Australasian legislation, although there is limited guidance within some Acts. An example is provided by the South Australian legislation referred to earlier11:

Do-not-resuscitate Considerations in Critical Care

Patients with acute, reversible illness conditions should have the prerogative of resuscitation. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) may be instigated in order to restore ventilation and circulation in patients, providing they do not have an irreversible or terminal illness. The decision to withhold CPR may be termed a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order in some jurisdictions. This reflects a decision against any further proactive treatment such as CPR, although there may be some limitations, such as ‘for defibrillation only’. Because each case must be considered on its merits, it is important to have clearly written medical orders/directives so that misinterpretations do not occur. Paramount in these cases is clear discussion, broad consultation and accurate documentation that reflects discussion between family and members of the critical care team and any subsequent decisions. Any directives must be clear to all those involved in the patient’s care. A management plan that incorporates assessment, disclosure, discussion and consensus building with the patient and family may be particularly useful.58

Euthanasia

Euthanasia, while being the subject of ongoing debate across the globe over many years, remains illegal in Australia and New Zealand. Euthanasia is the termination of a very sick person’s life in order to relieve them of their suffering. In most cases euthanasia is carried out because the person who dies asks for it. Confusion has occurred with some individuals unable to distinguish between the process of withholding and withdrawing treatment and that of euthanasia. The primary distinction relates to the issue of ‘intent’. If the primary intention of the intervention (e.g. a lethal injection) is to cause death, this may be regarded as euthanasia and may be tested in court. However, if the primary intention of an act is to reduce pain and suffering, this may not be regarded as euthanasia but may again be tested legally. The fact that the difference between the two is complex and contentious adds to the vigorous debate by those ‘for’ and ‘opposed to’ euthanasia: an ongoing question for many years in many countries. Religious opponents of euthanasia believe in the sanctity of life and that life is given by God. Other opponents fear that if euthanasia was made legal, the laws regulating it would be abused, and people would be killed who did not really want to die. Euthanasia is illegal in most countries. Those in favour of euthanasia argue that a civilised society should allow people to die in dignity and without pain, and should allow others to help them to do so if they cannot manage it on their own. The Netherlands legalised euthanasia, including doctor- assisted suicide, in 2002. The law codified a twenty-year-old convention of not prosecuting doctors who had committed euthanasia in very specific cases, under very specific circumstances.59 At times a patient may be influenced to request the cessation of treatment as a consequence of unrelieved and enduring pain and suffering, and/or depression. In these circumstances, where such a request may be thought to be inappropriate, it is proper to explore the patient’s feelings and treatment options and perhaps to develop an agreed future treatment plan. It may be useful to obtain assistance from a counsellor or other qualified professional.58

Nursing Advocacy

A commonly accepted view of nursing advocacy is where the nurse is portrayed as helping the patient discuss his or her needs and preferences, helping the patient make congruent choices, supporting the patient’s decision, and preventing others from impinging on the autonomy of the patient.60 This view of nursing advocacy is reflected by the Australian Code of Ethics for Nurses: specifically, nurses should ensure that patients are appropriately informed to make choices about their treatment and to maintain optimal self-determination (Value statement 2.3).61 One of the nurse’s roles is to initiate discussions with patients and families to get a true understanding of the cultural beliefs regarding end-of-life care. When the information is collected the health care team can collaboratively assist the patient and family to make appropriate decisions. Building trusting relationships is the objective.

Conscientious Objection

In Australia nurses are empowered by the Australian Code of Ethics61 to refuse to participate in any procedure that would violate their reasoned moral conscience (i.e. strongly held moral beliefs).56 In doing so, they must ensure that quality of care and patient safety are not compromised. In the critical care setting, such beliefs may impose on a nurse’s ability to care for a patient, in the case where the patient (or the patient’s family) has chosen to withdraw treatment, should the nurse hold strong moral beliefs about the sanctity of human life.

Brain Death

Brain death occurs in the setting of a severe brain injury associated with marked elevation of intracranial pressure. Inadequate perfusion pressure results in a cycle of cerebral ischaemia and oedema and further increases in intracranial pressure. When intracranial pressure reaches or exceeds systemic blood pressure, intracranial blood flow ceases and the whole brain, including the brainstem, dies.62 Determination of brain death requires that there is unresponsive coma, the absence of brainstem reflexes and the absence of respiratory centre function, in the clinical setting in which these findings are irreversible. In particular, there must be definite clinical or neuro-imaging evidence of acute brain pathology (e.g. traumatic brain injury, intracranial haemorrhage, hypoxic encephalopathy) consistent with the irreversible loss of neurological function.62

ANZICS recommends clearly that whenever death is determined using the brain death criteria, it is certified by two medical practitioners as defined by local legislation; consistent with the original intent of the Australian Law Reform Commission that the determination of brain death should have general application, whether or not organ and tissue donation and subsequent transplantation were to follow.62 Consistent with this, they also recommend that the time of death is recorded as the time when the second clinical examination to determine brain death has been completed. That is, when the process for determination of brain death is finalised, recognising that death will have occurred some indeterminate time before this but is only determined at this point.62

Brain death cannot be determined without evidence of sufficient intracranial pathology. Cases have been reported in which the brainstem has been the primary site of injury and death of the brainstem has occurred without death of the cerebral hemispheres (e.g. in patients with severe Guillain–Barré syndrome or isolated brainstem injury).63 Thus brain death cannot be determined when the condition causing coma and loss of all brainstem function has affected only the brainstem, and there is still blood flow to the supratentorial part of the brain. Whole brain death is required for the legal determination of death in Australia and New Zealand. This contrasts with the UK where brainstem death (even in the presence of cerebral blood flow) is the standard. Brain death is determined by clinical testing if preconditions are met; or imaging that demonstrates the absence of intracranial blood flow. The overall function of the whole brain is assessed. However, no clinical or imaging tests can establish that every brain cell has died.63 According to the US Uniform Determination of Death Act, brain death occurs when a person permanently stops breathing, the heart stops beating and ‘all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem’ cease. Yet determining brain death is a complex process that requires dozens of tests to make sure doctors come to the correct conclusion. With that goal in mind, the American Academy of Neurology issued new guidelines in 2010 – an update of guidelines first written 15 years ago, that call on doctors to conduct a lengthy examination, including following a step-by-step checklist of some 25 tests and criteria that must be met before a person can be considered brain dead.64 The goal of the guidelines is to remove some of the guess work and variability among doctors in their procedure for declaring brain death, that previous research has found to be a problem, and were developed based on a review of all of the studies on brain death published between 1995 and 2009. According to the guidelines, there are three major signs of brain death: coma with a known cause; absence of brain stem reflexes; and breathing has permanently stopped. Periodically, news reports will talk about a patient in a long-term coma that miraculously woke up, or someone in a persistent vegetative state who seems to have an inner life; one of the best known examples was the Terri Schiavo case in Florida USA, which pitted the woman’s parents against her husband. The 41-year-old Schiavo died in 2005, two weeks after the removal of a feeding tube that had kept her alive for more than a decade. But brain death should not be confused with other conditions, such as persistent vegetative or minimally conscious state, in which there is still some limited brain activity.

In a survey of 89 countries, legal standards on organ transplantation were present in 55 of 80 countries (69%). Practice guidelines for brain death for adults were present in 70 of 80 countries (88%). More than one doctor was required to declare brain death in half of the practice guidelines. Countries with guidelines all specifically specified exclusion of confounders, irreversible coma, absent motor response, and absent brainstem reflexes. Apnoea testing, using a PCO2 target, was recommended in 59% of the surveyed countries. This reflected uniform agreement on the neurologic examination with the exception of the apnoea test, however, it found other major differences in the procedures for diagnosing brain death in adults and recommended standardisation.65 Organ donation provides the only hope for some patients awaiting a new heart, lung or liver. It also improves the quality of life for patients on dialysis, and it restores sight to injured or blind patients. For an organ to be donated in Australia or New Zealand, the process involves certification of death, lack of objection from the deceased/senior available next-of-kin, consent of the coroner (if applicable), and permission of the designated officer of the hospital (see Chapter 27). Certification of brain death is pivotal and inextricably linked to the organ donation and transplant process, as it allows the retrieval of well-perfused organs in good condition from patients who have already been certified dead (namely the ‘beating-heart donor’). Diagnosis of brain death must be unequivocal, thorough and transparent, so that it is regarded by family and healthcare team as an absolute diagnosis without question.66

Death requires documentation from a legal and social position, although advances in modern technology have blurred the distinction between life and death. The progression to development of specific brain death criteria was to ensure unequivocal concordance in its diagnosis. Brain death is established by documentation of irreversible coma, loss of brainstem reflexes and respiratory centre function, or by the demonstration of cessation of intracranial blood flow (see Chapter 27).

• absence of circulation as evidenced by absent arterial pulsatility for a minimum of two minutes, as measured by feeling the pulse or, preferably, by monitoring the intra-arterial pressure.

When all of these criteria have been met, the patient is determined to be dead and therefore organ removal may proceed.62

Organ Donation

According to ANZICS, dying is a process rather than an event.62 The determination and certification of death indicate that an irrevocable point in the dying process has been reached, not that the process has ended. Determination of death by any means does not guarantee that all bodily functions and cellular activity, including that of brain cells, have ceased. Several tissues can be retrieved for transplantation long after death has been determined by cessation of circulation. Similarly, after death has been determined by loss of whole brain function, the circulation can be maintained for hours or days to enable organs to be retrieved. Maintaining the circulation can continue even longer: for example, in the case of a pregnant woman, so that the fetus can reach viable independent existence.

• no person, organisation or company should profit financially from organ or tissue donation

• neither the estate of an organ or tissue donor nor his or her family should incur any cost from the processes that occur to facilitate organ and tissue donation.

People who donate following brain death remain the ‘gold standard’ for organ donation. They are the only source of viable hearts after death and are able to provide much better livers for transplantation. Notably, the increase in donation after cardiac death (DCD) is helping to increase the numbers of kidneys available for transplantation substantially. However, the limitations of this potential donor source need to be recognised alongside the complexities and sensitivities of the process. In Australia a national DCD Protocol, led by the National Health and Medical Research Council, has been progressed.66

1. Organ and Tissue Donation by Living Donors: Guidelines for Ethical Practice for Health Professionals: outlines ethical practice for health professionals involved in living organ and tissue donation and provides guidance on how these principles can be put into practice.67

2. Living Organ and Tissue Donation: Guidelines for Ethical Practice for Health Professionals: aims to help people think through some ethical issues and make decisions about living organ and tissue donation.68

3. Organ and Tissue Donation After Death, for Transplantation: Guidelines for Ethical Practice for Health Professionals: outlines ethical principles for health professionals involved in donation after death and provide guidance on how these principles can be put into practice.69

4. Making a Decision about Organ and Tissue Donation after Death: this booklet is derived from Organ and Tissue Donation after Death, for Transplantation: Guidelines for Ethical Practice for Health Professionals, and aims to help people think through some ethical issues and make informed decisions about organ and tissue donation after death.68

Donation after Cardiac Death

There is increasing recognition of the role of donation after cardiac death (DCD) activity in Australia, New Zealand and globally. So-called ‘cardiac death’ includes death of the person as a whole, with death of the brain being an inevitable consequence of permanent cessation of the circulation. The organ yield (i.e. number of organs usefully transplanted) may be less in a DCD donor than that of a brain death donor due to the differences in timing and length of ‘warm ischaemic’ time. See also Chapter 27.

Nurses’ Attitudes to, and Knowledge of, Organ Donation

Some critical care nurses have dedicated roles in the organ donation team and may be integral in providing knowledge and leadership in all aspects of donation and high-quality care in the end-of-life care process. They offer the option of donation as appropriate to families and supporting their decisions at extremely sad and stressful times. Communication and interpersonal skills are essential. Trustworthy relationships maximise identification and referral.55

The issue of organ donation also poses personal ethical challenges for some individuals, perhaps related to beliefs held about the integrity of the human body and the interests of the donor and recipient. Some literature suggests that the current understanding of brain death is flawed, in that the diagnosis may be confused with ‘profound coma associated with massive brain damage’,70 while acknowledging that it seems apparent that inadequate brain death testing, or misapplication of brain death criteria, is likely to be related to a wrong diagnosis.

Some distrust about brain death is evident in numerous countries. One Australian study showed that 20% of families of brain-dead patients continued to harbour doubts about whether the patient was actually dead, and a further 66% of relatives accepted the death, but felt emotionally that the patient was still alive.71 Researchers describe the contradictions and ambiguities associated with caring for brain dead patients, particularly the ambiguity that accompanies caring for a brain dead body that exhibits traditionally accepted signs of life.72,73

In a recent Australian study of experienced intensive care nurses, almost half the participants did not regard brain death as a state of complete death.74 Further, there were no correlations between brain death perception and the independent variables of religious affiliation, intensive care experience, experience of nursing brain dead patients, knowledge of brain death diagnostic procedures, educational background, and knowledge of Australian legal definitions of death. Participants who were non-accepting or ambivalent may not have perceived that the medicolegal construct of brain death was congruent with their ‘personal foundational death notions’.74 Consequently, the authors cautioned against equating lack of acceptance with a lack of knowledge of the clinical aspects of brain death, but rather suggested that for some nurses, the concept of brain death may run counter to their previously-formed concept of death. It is important that critical care nurses possess a thorough understanding of brain death, and that they reflect on their personal conceptions about death.

The issue of language used is also relevant to doctors and nurses, with the use of the depersonalising terms ‘cadaver’ and ‘harvesting’ perhaps serving to psychologically protect staff but perhaps acting as a barrier to effective communication and understanding.75 The use of such language may reinforce the conceptual gap described above between a personal notion of death and brain death.

Intensive care nurses are in a good position to foster a positive attitude towards organ donation through educational and supportive actions with the family of the patient. It is recognised as important to allow the family time to come to terms with the death of the patient before making their decision about donation. It may be useful to note that the majority of donor families say that they would make the same choice again if given the opportunity.76 Further discussion of the organ consent, donation and transplant processes is provided in Chapter 27.

The role of the nurse in the organ donation process includes supporting the relatives, offering explanation and support, in addition to specific therapy delivery in an operational sense. In some ICUs, nurses participate in seeking consent from relatives for organ donation, a task that has been shown to be very stressful.77 This stress arises from the perception that the intrusion may inflate the distress of the family. However, consenting to organ donation in itself does not hinder or prolong the grief process.78

Research from the USA has noted a significant positive correlation between higher knowledge levels possessed by intensive care nurses and more positive attitudes towards organ donation.79 In addition, nurses in the UK who were found to hold positive attitudes to organ donation were more likely to broach and discuss the possibility of organ donation with families.80 However, acceptance of the principle of organ donation among ICU nurses was higher than support for donation of their own organs or those of a family member.79 This difference was attributed to some nurses not internalising the particular personal values, attitudes and interests related to the concept of organ donation, therefore not being able to act on their beliefs.

This paradox may be reflected in the general public, as an Australian study found that, while surveys of the general public continue to show considerable support for organ donation programs, in practice donation rates continue to be low.81 In the USA, of those people who state that they support organ donation, only about half actually consent to donate.76

Organ donation occurs at a time of great emotional distress. The terminology and phraseology in this section are necessarily factual, and might appear unsympathetic to those most closely affected by organ donation. This dispassionate reporting of events and outcomes should not be taken as disrespectful to deceased donors or their families, or to the amazing gift that they make.55

Australia was a world leader in clinical outcomes for transplant patients in 2010, and over 30,000 Australians have benefited since transplantation first became a standard treatment option. More than ninety per cent of Australians support organ donation.55 Despite this, Australia has a low rate of donation and consequently a new national authority, The Australian Organ and Tissue Authority (AOTA) was established in Australia in 2009 with the mandate to significantly improve organ and tissue donation and transplantation and to move Australia from a low rate of donation to a leading country performer. This national reform package was based on a World’s Best Practice approach and plan, learning from leading country performers such as Spain, France, Belgium, Austria and the USA. Awareness and engagement of the community, non-government sectors, donor families, and others involved in increasing organ and tissue donation, is paramount with a national approach to in-hospital systems, resources and education of the community and clinicians.68

In Australia, organ and tissue donation only occurs with the agreement of the next of kin following the death of a potential donor. Australian doctors would not proceed with organ donation without this agreement which is necessary for legal, ethical and medical reasons. Ensuring family members understand each other’s wishes regarding organ and tissue donation, and improving consent rates at the time of request is fundamental to improving donation rates. Equally important is adequate training of health professionals to sympathetically and sensitively approach the grieving family with full knowledge of the process.66

Box 5.3

The Intruder

In 2009, Francine Wynn explored a philosophical reflection written by John-Luc Nancy on surviving his own heart transplant. In The Intruder, Luc raises central questions concerning the relations between what he refers to as a ‘proper’ life, that is, a life that is thought to be one’s own singular ‘lived experience’, and medical techniques. Nancy describes the temporal nature of an ever-increasing sense of strangeness and fragmentation which accompanies his heart transplant and opens up the concept of transplantation in terms of the problematic ‘gift’ of a ‘foreign’ organ, the unremitting suffering intrusiveness of the treatment regimen, and the living of life as ‘bare life’. Nancy offers no answer to this dilemma, but instead calls on others to think about the meaning or ‘sense’ of the prolonging of life and deferring of death.55

Ethics in Research

Respect for ethical codes is a requirement for all those conducting human research. There are various ethical guidelines. For example, the Declaration of Helsinki is regarded as authoritative in human research ethics. In the UK, the General Medical Council provides clear overall modern guidance in the form of its Good Medical Practice Statement. Other organisations, such as the Medical Protection Society in the UK and a number of university departments, are often consulted by British doctors regarding issues relating to ethics. With respect to the expected composition of such bodies in the USA, Europe and Australia, the following applies: USA recommendations suggest that Research and Ethical Boards (REBs) should have five or more members, including at least one scientist, one non-scientist and one person not affiliated with the institution. The REB should include people knowledgeable in the law and standards of practice and professional conduct. Special memberships are advocated for handicapped or disabled concerns, if required by the protocol under review. The European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) suggests that REBs include two practising doctors who share experience in biomedical research and are independent from the institution where the research is conducted; one lay person; one lawyer; and one paramedical professional, e.g. nurse or pharmacist.82 Healthcare research in Australia is performed in accordance with guidelines issued by the NHMRC, while in New Zealand the guidelines are issued by the Health Research Council (HRC). Both Councils have statutory authority, and health service and university Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) (Australia) and both Health and Disability Ethics Committees and Institutional Ethics Committees (IECs) (New Zealand) are bound to consider research proposals in accordance with the relevant recommended processes and procedures outlined below. In subsequent discussion the above committees in both countries are referred to as ethics committees (ECs) for clarity, and operate in accordance with the following:

• The NHMRC National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007, is aimed primarily at researchers, and provides a summary of principles.8

• The NHMRC Human Research Ethics Handbook 2001 expands these principles, offers commentary and legal discussion, and is aimed at both HREC members and researchers.83

• The NHMRC Values and Ethics: Guidance for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research provides guidance to researchers, HRECs and Aboriginal-specific HRECs or subcommittees on the conception, design and conduct of research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.84 It has the same status as the National Statement. The documents are to be used together.

• The New Zealand Operational Standard for Ethics Committee (OS)12 provides guidance on principles that should be considered when reviewing research proposals.

• In addition, the HRC Guidelines on Ethics in Health Research expands on the above standards and should be used in combination (both documents are available online, see Online resources).

• Individual Institutional/Hospital Research Ethics Committees (IECs/HRECs) and Regional Ethics Committees have their own requirements for research protocol ethics submission, compliance, monitoring and complaints handling.

Application of Ethical Principles

When considering human clinical research in the context of critical care, the concept of respect for persons is linked to the ethical principle of autonomy.8 In human research, respect for persons demands that participants receive adequate information and enter voluntarily without coercion. Surrogate consent may be applicable in critical care areas when research activities are being considered.85 Other important and relevant ethical principles for researchers are beneficence and non-maleficence. Beneficence in the research context is expressed by the researcher’s responsibility to minimise the risk of harm or discomfort to any research participants.8 Research protocols should be designed to ensure that respect for dignity and wellbeing takes precedence over expected knowledge benefits. With regard to justice in research, this requires that within a population there is a fair distribution of ‘benefits and burdens’ for research participation, although the proportion of these will vary depending on the research activity.

When recruiting research participants it is important to ensure that any initial approach is made appropriately. When the study involves recruitment of hospital inpatients, this approach should be made by someone directly involved in their care, with the aim of seeking permission to then be approached by the investigators specifically about the research. If the study involves recruitment of individuals from the community, this can be done by public display (e.g. flyers, published advertisements), providing the contact details of the researcher. Control of involvement is then with the participant to make contact with the researcher. While these processes may be interpreted as reducing or slowing recruitment, the principles of respect and autonomy for persons are upheld as the potential for coercive recruitment is reduced. Another guiding value in ethical research is that of integrity. This value requires that the researcher be committed to the search for knowledge and to the principles of ethical research, conduct and results dissemination.8

Human Research Ethics Committees

Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) play a central role in the international system of ethical supervision of research involving humans. HRECs review proposals for research involving humans to ensure that the research is soundly designed, and is conducted according to high ethical standards such as those articulated in Australia in the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (known as the National Statement). Many other countries have similar systems and statements or guidelines. While HRECs primarily fulfil a guardian role, an often overlooked secondary purpose set out in the preamble to the National Statement is to ‘facilitate research that is, or will be, of benefit to the researcher’s community or to humankind’.8 Thus HRECs are seen as having a role in promoting good research and good ethical practice, as well as guarding against poor research and poor ethical practice.

For a series of useful case studies related to complex and challenging research governance debate, refer to NHMRC’s Challenging Ethical Issues in Contemporary Research on Human Beings 2006.86

Research proposals involving human participants must be reviewed and approved by a formally constituted EC that is established by, and advises, an institution or organisation regarding ethical approval for research projects. An EC must ensure that it is sufficiently informed on all aspects of submitted research proposals, and is charged with the responsibility to ensure that investigators undertaking human research are adequately knowledgeable and skilled in the research question and associated methodology. Additional expertise may be sought either from individuals or from specific dedicated ‘shared assessment scheme’ groups as considered necessary.19

Presentation in person to HRECs in Australia is not common but may be requested for complex protocols.18 In New Zealand, presentation in person to the IEC, while not compulsory, is common practice and highly recommended, as it often provides additional clarification.

Clinical Ethics

Within the clinical ethics remit, it is important to:

1. Organise and use interpreters appropriately.

2. Create care environments that facilitate optimal patient and family control of decisions.

3. Work collaboratively with other healthcare workers in a culturally sensitive and competent manner.

4. Identify and address bias, prejudice and discrimination in healthcare service delivery.

5. Integrate measures of patient satisfaction into improvement programs.

Privacy and Confidentiality

Privacy is a fundamental human right recognised in all major international treaties and agreements on human rights. Nearly every country in the world recognises privacy as a fundamental human right in their constitution, either explicitly or implicitly. Most recently drafted constitutions include specific rights to access and control one’s personal information. New technologies are increasingly eroding privacy rights. These include video surveillance cameras, identity cards and genetic databases. There is a growing trend towards the enactment of comprehensive privacy and data protection acts around the world. Currently over 40 countries and jurisdictions have or are in the process of enacting such laws.87 Countries are adopting these laws in many cases to address past governmental abuses (such as in former Eastern Bloc countries), to promote electronic commerce, or to ensure compatibility with international standards developed by the European Union, the Council of Europe, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Surveillance authority is regularly abused, even in many of the most democratic countries. The main targets are political opposition, journalists and human rights activists. The US government is leading efforts to further relax legal and technical barriers to electronic surveillance. The Internet is coming under increased surveillance.88

The Privacy Act 1993 is based on a series of 12 information privacy principles (IPPs) (in Section 6) that outline the purpose, source, collection, access, storage, disclosure and use of information throughout New Zealand. In addition the Act contains various codes of practice that relate to the use of information, and provides detail regarding exemptions from the IPPs. Of note, the Act also details (in Sections 12 – 25) the establishment and operation of a Privacy Commissioner (see Online resources for website address). The purpose of the Commissioner is to oversee the implementation of the IPPs, including in education and compliance issues.

The Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988 sets out (in Section 14) 11 IPPs that govern the conduct of Australian Commonwealth agencies in their collection, management and use of data containing personal information.89 The IPPs describe that agencies are not permitted to use or disclose, in identifiable form, records of personal information for research and statistical purposes, unless specifically authorised or required by another law, or unless the individual has consented to their use or disclosure (Privacy Act 1988). To avoid breaches of the above privacy legislation where access to health information may be required for research purposes, the NHMRC issued Guidelines under Section 95 of the Privacy Act 1988 (s95 Guidelines). These were developed to provide a framework for the conduct of medical research where identifiable information held by any Commonwealth agency (e.g. a public hospital) needs to be used without consent, i.e. ‘if the public interest in the promotion of the research is of a kind that outweighs “to a substantial degree” the public interest in maintaining adherence to the IPPs’.90

These were followed by the Guidelines approved under Section 95A of the Privacy Act 1988 (s95A Guidelines) to provide a similar framework (to the s95); broadened to encompass the private sector.90 These include ten national privacy principles (NPPs) that set the minimum standards for the private sector.

In addition, each state and territory has additional jurisdictional regulatory guidelines that apply to privacy and use and disclosure of health information. The Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory adhere only to the Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988. A summary of these complex arrangements for the states, however, regarding disclosure of personal health information, adapted from Thomson,91 is as follows.

• Victoria: The Health Records Act 2001 (Vic.) and the Information Privacy Act 2000 (Vic.) permit disclosure if it is reasonably necessary for research in the public interest; if it is impracticable to seek consent; if the agency believes that the recipient will not disclose the information; that the publication does not identify individuals and there is a favourable HREC review.

• Queensland: In a Queensland hospital, Information Standard 42A imposes the same criteria as the federal NPPs. It must be impracticable to seek consent and an HREC must complete a favourable review, using the guidelines under Information Standard 42A. However, section 63F of the Health Services Act 1991 (Qld) permits disclosure of information without consent only if the Chief Executive of the state health department considers it in the public interest.

• South Australia: In SA, a Cabinet instruction, based on federal IPPs, governs use and disclosure. That instruction does not permit relaxation of those standards, although the Privacy Committee may exempt the hospital, on conditions, from the requirements. There is also the Department of Health Code of Fair Information Practice 2004.

• Western Australia: The proposal for use and disclosure of personal information is reviewed by the Confidentiality of Health Information Committee.