35 Ethical Issues

Case 1

The family member of a recently deceased ICD patient recounted the following in an interview1:

The most common ethical issue facing physicians and other health care providers who care for patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) is that of device deactivation in patients nearing the end of their life or who otherwise request that device therapies be deactivated. Most clinicians (physicians, nurses, and other health care providers) who care for patients with CIEDs have participated in device deactivations.2 However, their understanding of the legal and ethical issues surrounding device deactivation varies, as do clinicians’ attitudes toward deactivation.2,3 Further, as one study reported, 20% of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) patients receive shocks in the last weeks of their lives, as illustrated by Case 1. Few patients or families discuss the option with device deactivation with their physicians before the days preceding death, even patients with “do not resuscitate” orders.1 Likewise, few clinicians initiate discussions with patients or family members regarding device deactivations, even when the patient’s situation is terminal.

As the population of patients benefiting from and receiving CIEDs continues to grow, clinicians will increasingly care for CIED patients dying of nonarrhythmic, often slow processes, such as cancer and heart failure. Situations such as described in Case 1, in which CIEDs cause pain and reduce quality of life in patients at the end of their life, may likely become more common. Case 2 illustrates how management of CIED therapies in dying patients can be addressed in ways more beneficial to patients and families. To address the uncertainties surrounding CIED deactivation and provide direction for clinicians in these difficult circumstances, the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) published recommendations regarding deactivation, with input from electrophysiologists, patients, and representatives from the fields of geriatrics, palliative care, psychiatry, nursing, law, ethics, and divinity, as well as industry and patient groups.4

Ethical and Legal Principles Underlying CIED Deactivation

Ethical and Legal Principles Underlying CIED Deactivation

Basic ethical principles applicable to patient care include respect for patient autonomy (the duty to respect patients and their rights of self-determination), beneficence (the duty to promote patient interests), nonmaleficence (the duty to prevent or not harm patients), and justice, referring in part to the duty to treat patients and distribute health care resources fairly.5 Informed consent, the most important legal doctrine in the clinician-patient relationship, derives from the ethical principle of respect for persons; autonomy is maximized when patients understand the nature of their diagnoses and treatment options and participate in decisions about their care. The rationale for informed consent is simple: it is the patient’s body and life—the patient must live with the consequences of the treatment—and thus the patient has the most at stake in the decision.6 Clinicians are ethically and legally obligated to ensure that patients are informed about their diagnoses and treatment options.7,8

The U.S. courts have ruled that the right to make decisions about medical treatments is both a common law (derived from court decisions) right based on bodily integrity and self-determination and a constitutional right based on privacy and liberty.6 A corollary to informed consent is informed refusal. A patient has the right to refuse any treatment, even if the treatment prolongs life, or death would follow a decision not to use it. A patient also has the right to refuse a previously consented treatment if the treatment no longer meets the patient’s health care goals, if those goals have changed (e.g., from prolonging life to minimizing discomforts), or if the perceived burdens of the patient’s illness (e.g., quality of life) and ongoing treatment outweigh the perceived benefits of ongoing treatment.6,9–11 Honoring these decisions is an integral part of patient-centered care. If a clinician initiates or continues a treatment that a patient has refused, then ethically and legally the clinician is committing “battery,” regardless of the clinician’s intent.7 Finally, granting requests to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from patients who do not want them, is respecting a right to be left alone and to die naturally of the underlying disease, a legally protected right based on the right to privacy. This has been phrased as “a right to decide how to live the rest of one’s life.”

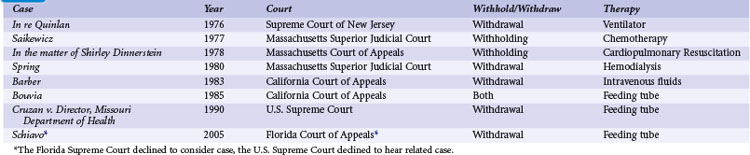

A patient’s right to withdraw unwanted treatment has been consistently upheld by U.S. courts (Table 35-1). In the In re Quinlan case, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that the patient had both common law and constitutional rights to refuse continued ventilator support, even though her clinicians believed she would die without it.12 In the Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health case, which involved a feeding tube, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the same way; that is, patients have the right to refuse life-sustaining treatments. The Court also ruled that a feeding tube was a medical treatment and that it did not have unique status.13 Whether a feeding tube had unique status was raised again during the Terri Schiavo case. The courts again ruled adult patients have a constitutional right to refuse any treatment, including life-sustaining treatments, and that there is no legal difference between withdrawing an ongoing treatment and not starting it in the first place.14

TABLE 35-1 Landmark Legal Cases Confirming the Right to Withhold or Withdraw Life-Sustaining Therapies

In none of these cases did the courts distinguish between types of life-sustaining treatments. The law applies to the person, and informed consent is a right of the patient—it is not specific to any one medical intervention.6,14–16 Thus, even though the Supreme Court has not specifically commented on the question of pacemaker or ICD deactivation, because CIEDs deliver life-sustaining therapies, discontinuation of these therapies is clearly addressed by the previous Supreme Court precedents upholding the right to discontinue life-sustaining treatment.

In addition, these rights extend to patients who lack decision-making capacity, through previously expressed statements (e.g., advance directive) and surrogate decision makers.11,14,17 When patients lack decision-making capacity because of medical illness (e.g., dementia), clinicians must rely on surrogates to make decisions. If the patient has an advance directive (AD) that identifies a surrogate, the patient’s choice of surrogate should be respected7 (see later). In the absence of an AD, clinicians must identify the legally recognized appropriate surrogate. The ideal surrogate is one who best understands the patient’s health care–related goals and preferences. Many U.S. states, however, specify by law a hierarchy of surrogate decision makers (e.g., spouse, followed by adult child, and so on). When making decisions, a surrogate should adhere with the instructions in the patient’s AD (if one exists) and base decisions on the patient’s—not the surrogate’s—values and preferences if known (i.e., the “substituted judgment” standard).18

Although both the law and ethics are clear—a patient has the right to refuse and request the withdrawal of CIED therapies regardless of whether he or she is terminally or irreversibly ill, and regardless of whether the therapies prolong life and death would follow a decision not to use them7—some clinicians who care for patients with CIEDs see a moral distinction between deactivating an ICD and deactivating a pacemaker, particularly in a dependent patient.2 However, while some have questioned whether pacemaker deactivation is similar to assisted suicide or euthanasia,2 there are several key differences between withdrawal of CIED therapies and assisted suicide. First is the issue of clinician intent. When a physician complies with a patient’s request to deactivate a device, the physician’s intent is to remove a treatment that is perceived by the patient as burdensome or is simply unwanted. Although this may have the effect of allowing the patient to die of an underlying disease,12,16,19 hastening death should not be the clinician’s primary intent.7,10,20 In contrast, in assisted suicide, the patient intentionally terminates his own life using a lethal method provided or prescribed by a clinician. In euthanasia, the physician directly and intentionally terminates the patient’s life (e.g., lethal injection). The second point differentiating withdrawal of an unwanted therapy from assisted suicide and euthanasia lies in the cause of death. In assisted suicide or euthanasia, death is caused by the intervention provided, prescribed, or administered by the clinician. In contrast, when a patient dies after a treatment is refused or withdrawn, the cause of death is the underlying disease. There are clearly nuances to this issue. For example, a pacemaker-dependent patient with depression may request deactivation of the pacemaker because life itself is burdensome. In such situations it is important to determine the decision-making capacity of the patient.

The U.S. Supreme Court decisions have made a clear distinction between withdrawing life-sustaining treatments and assisted suicide and euthanasia. In the case of Vacco v. Quill,21 Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote:

The Court ruled that all patients have a constitutional right to refuse treatment, but no one has a constitutional right to assisted suicide or euthanasia. In another case,22 the Court ruled that clinicians can legally (and should, from an ethical perspective) provide patients with whatever treatments needed to alleviate suffering, such as morphine, even if the treatments might hasten death. Criminality is determined by the clinician’s intent.

Legal precedent does not distinguish between types of unwanted therapies, but there are aspects of pacing therapies in a dependent patient that some clinicians have found problematic. For example, ICD therapies are intermittent whereas pacemaker therapy in a pacemaker-dependent patient is continuous; death might not occur immediately after ICD deactivation, whereas death might occur quickly after pacemaker deactivation. However, widespread agreement exists that withdrawing other continuous life-sustaining treatments, such as mechanical ventilation, is ethically and legally permissible. Similarly, clinicians may consider duration of therapy as morally important when considering requests to withdraw life-sustaining treatments. However, withdrawal of other long-term life-sustaining treatments, such as hemodialysis and artificial hydration and nutrition, is well accepted.23 Another concern expressed about withdrawing CIED therapies is that the devices, unlike other life-sustaining treatment, are completely internal. However, the ethical and legal principles involved in the right to refuse treatment are not based on the location of the therapy. Thus, the fact that pacemakers provide therapy that is continuous, internal, and of long duration does not detract from the permissibility of carrying out requests to withdraw this therapy from patients who no longer want it.

Some disagreement exists regarding whether a pacemaker is a substitutive therapy, one that substitutes for a pathologically lost function, or a replacement therapy, one that replaces a pathologically lost function. There is agreement that substitutive life-sustaining treatments, such as hemodialysis for kidney failure or a ventilator for respiratory failure, can be withdrawn. A replacement therapy, such as kidney transplantation for kidney failure, literally becomes “part of the patient” and provides the lost function in the same fashion as did the patient’s own body. Replacement therapies also respond to physiologic changes in the host and are independent of external energy sources and control of an expert. Removing or withdrawing a replacement life-sustaining treatment has been characterized as “euthanasia.”23 CIED therapies, including pacemaker support in a pacemaker-dependent patient, lack the features of replacement therapies and therefore are most often characterized as “substitutive,”24 although this distinction has been questioned.19 A transplanted kidney, however, has all the features of a replacement therapy. Most would regard carrying out a request to deactivate a pacemaker in a terminally-ill patient as far less morally problematic than carrying out a request to remove a transplanted kidney in the same patient. Deactivating a pacemaker is noninvasive and does not introduce a new pathology (although it may precipitate heart failure symptoms). Removing a kidney, however, is invasive and introduces a new pathology (i.e., a wound).

Ethical Principles Underlying, the Decision-Making Process

Who decides about device deactivation? Ethically and legally, competent patients (or their surrogates) have authority to make decisions. Patients’ decisions have priority over clinicians’ decisions. Because a clinician regards a patient’s decision as “wrong” does not mean the decision is irrational. What criteria should go into making the decision? The patient and physician together must determine a treatment’s effectiveness and the benefits and burdens in the context of the patient’s illness and quality of life. A treatment’s effectiveness is its ability to alter the natural history of a disease. CIEDs are effective, for example, in bypassing life-threatening cardiac conduction abnormalities or treating fatal arrhythmias. However, treatment effectiveness is not the same as treatment benefits and burdens. Benefit is determined by the patient: the patient’s assessment of the treatment’s value. Burden is also determined by the patient: the patient’s assessment of the existing and potential discomforts, costs, and inconveniences associated with the illness and its treatment as the patient perceives it.9 Each patient is unique and weighs such benefits and burdens in relation to their own values, preferences, and health care–related goals. What one patient perceives as beneficial and nonburdensome may be viewed by another patient as nonbeneficial and burdensome. Because benefit and burden are determined by the patient, a patient may decide the burden of CIED therapy outweighs the benefit even if he is not terminally ill.

Ethics consultation is not required before device deactivation. However, this may be helpful in ambiguous situations such as conflict between members of a family or disagreement between members of the health care team caring for a patient, or caregivers may find that additional support is needed when pursuing a particular treatment course.25 If the decision-making capacity of the patient is in question, or if there are suspicions of coercion, ethics consultation can also be helpful. The Joint Commission requires that health care institutions have processes for addressing ethical concerns that arise in the care of patients.26 Case 3, describing disagreement among both family and caregivers, and case 4, an ambiguous case illustrating possible coercion, illustrate examples in which ethics consultation may be helpful:

Advance care planning can often prevent ethical dilemmas at the end of life. In this process, which promotes patient autonomy, a patient identifies his or her values, preferences, and goals regarding future health care (e.g., at the end of life) and a surrogate decision maker in the event the patient loses decision-making capacity.7 Ideally, the patient should discuss values and preferences with care providers and potential surrogate decision makers, who should document them in the patient’s medical record, and the patient should complete an advance directive. There are two forms of ADs: the durable power of attorney for health care and the living will. The durable power of attorney for health care allows the patient to specify a surrogate in the event the patient loses decision-making capacity. The living will allows the patient to list specific health care–related values, goals, and preferences. From an ethics standpoint, clinicians should view the AD as an extension of the autonomous person and therefore should respect the values, goals, and preferences listed in the AD. From a legal standpoint, all 50 U.S. states recognize ADs as an extension of the autonomous person. In fact, the Patient Self-Determination Act, passed by Congress in 1990 in response to the Cruzan decision, requires that health care institutions that participate in Medicare and Medicaid programs ask patients whether they have an AD, inform patients of their rights to accept or refuse medical treatments and to create and execute an AD, and to incorporate ADs into patients’ medical records.27

Rights and Responsibilities of Clinicians for Whom Deactivation Is Counter to Their Personal Beliefs

Regardless of the ethical and legal permissibility of carrying out requests to withdraw CIED therapies from patients who have (or their surrogate has) made this decision, clinicians—like patients—are moral agents whose personal values and beliefs may lead them to prefer not to participate in device deactivation. A recent survey found that about 10% of clinicians who care for patients with CIEDs view pacemaker deactivation in a pacemaker-dependent patient as a form of assisted suicide or euthanasia.2 Others object to pacemaker deactivation because they believe pacemaker therapy does not prolong the dying process or cause physical discomfort (unlike ICD shocks) and that pacemaker deactivation may cause discomfort (e.g., worsened heart failure symptoms).28 These burdens are ultimately determined by the patient, but clinicians and others, including industry employed allied professionals, should not be compelled to carry out device deactivations if they view the procedure as inconsistent with their personal values.8,28 Under these circumstances, the clinician should inform the patient of the clinician’s preference not to perform CIED deactivation. However, as described in the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Medical Ethics,29 the clinician should not impose his or her values on or abandon the patient and should ensure that they do not cause the patient emotional distress.30 Instead, the clinician and patient should work to achieve a mutually agreed-upon care plan. If such a plan cannot be achieved, the primary clinician should involve a second clinician who is willing to comanage the patient and provide legally permissible care and procedures, including CIED deactivation.28,29 It is important for the health care team to recognize and address any conflicts within the team. It is also the responsibility of the institution to ensure that services that are legal and that may be requested by the patient are available.

Preventing Both Ethical Dilemmas and Painful Shocks at End of Life: Importance of Early, Proactive Communication

Case 5

A 74-year-old woman had an ICD inserted 5 years ago after her first episode of ventricular tachycardia. As her heart disease progressed, the episodes of ventricular tachycardia increased. While at home one afternoon, her defibrillator shocked her several times, and she was admitted to the hospital. She went in and out of consciousness and was hemodynamically unstable for the next 72 hours. After a long family meeting, her family and cardiologist decided that no further aggressive treatments would be continued and that her care would focus on comfort. During the night, her ICD shocked her 10 times, while her nurse tried desperately to contact someone to turn off her ICD. Finally, at 3 am, the cardiologist came in and deactivated the ICD. She died 2 hours later.17

Timely and effective communication among patients, families, and health care providers is essential to informed consent and to prevent situations such as described in Case 5. Effective communication includes determining the patient’s goals of care, helping the patients weigh the benefits and burdens of device therapy as his clinical situation changes, clarifying the consequences of deactivation, and discussing potential alternative treatments, as well as encouraging the patient to complete an AD. Clinicians must take a proactive role in discussions about the option of deactivation in the context of the patient’s goals for care. These conversations should continue over the course of the patient’s illness. As illness progresses, patient preferences for outcomes and the level of burden acceptable to a patient may change.32,33 Advanced care planning conversations improve outcomes for both patients and their families,34 as patients with ICDs who engage in advance care planning are less likely to experience shocks while dying because ICD deactivation has occurred.35 Studies show that patients and families desire conversations about end-of-life care.36–38

Few patients with CIEDs discuss device deactivation with their clinicians or know that device deactivation is an available option.1,3,31 Even though many patients with CIEDs have ADs, very few of them mention the device specifically in their ADs.39 Clinicians must take a proactive role in initiating discussions about the option of deactivation, from the time of implantation throughout a patient’s life as the clinical situation changes (Table 35-2). The complexity of these conversations, however, is evident in data from physicians demonstrating that although they believe they should engage in these types of conversations with patients, they rarely do.1,3,31

TABLE 35-2 Physician-Initiated Discussions with Implant Patients

| Timing of Conversation | Points to Discuss | Helpful Phrases to Consider |

|---|---|---|

| Before implantation | Clear discussion of benefits and burdens of device. Brief discussion of potential future limitations or burdensome aspects of device therapy. Encourage patients to have some form of advance directive. Inform of option to deactivate device in the future. |

“It seems clear at this point that this device is in your best interest, but you should know at some point if you become very ill from your heart disease or another process you develop in the future, the burden of this device may outweigh its benefit. While that point is hopefully a long way off, you should know that turning off your defibrillator is an option. ” |

| After an episode of increased or repeated firings from an ICD | Discussion of possible alternatives, including adjusting medications, adjusting device settings, and cardiac procedures to reduce future shocks. | “I know that your device caused you some recent discomfort and that you were quite distressed. I want to work with you to see if we can adjust the settings to assure that the device continues to work in the appropriate manner. If we can’t get you to that point, then we may want to consider turning it off altogether, but let’s try some adjustments first.” |

| Progression of cardiac disease, including repeated hospitalizations for heart failure and/or arrhythmias | Reevaluation of benefits and burdens of device. Assessment of functional status, quality of life, and symptoms. Referral to palliative and supportive care services. |

“It appears as though your heart disease is worsening. We should really talk about your thoughts and questions about your illness at this point and see if your goals have changed at all.” |

| When patient/surrogate chooses a “do not resuscitate” (DNR) order* | Reevaluation of benefits and burdens of device. Exploration of patient’s understanding of device and how patient conceptualizes it with regard to external defibrillation. Referral to palliative care or supportive services. |

“Now that we’ve established that you would not want resuscitation in the event your heart were to go into an abnormal pattern of beating, we should reconsider the role of your device. In many ways it is also a form of resuscitation. Tell me your understanding of the device, and let’s talk about how it fits into the larger goals for your medical care at this point.” |

| Patients at end of life | Reevaluation of benefits and burdens of device. Discussion of option of deactivation addressed with all patients, although deactivation not required. |

“I think at this point we need to reconsider your [device]. Given how advanced your disease is, we need to discuss whether it makes sense to keep it active. I know this may be upsetting to talk about, but can you tell me your thoughts at this point?” |

* Patients may choose to forego intubation, CPR, and external defibrillation while at the same time deciding to keep the defibrillation function of their ICD active. A patient’s choice to be “DNR” may or may not be concomitant with a decision to withdraw CIED therapy, as resuscitation interventions and the ICD each carries its own benefits and burdens.

Modified from Lampert R, Hayes DL, Annas GJ, et al: Heart Rhythm Society Expert Consensus Statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm 7:1008-1026, 2010.

Discussion of Device Deactivation with Overall Goals of Care

Table 35-3 outlines the steps needed for goal-directed communication and some useful phrases to begin conversations at each point. These conversations should include a discussion of quality of life, functional status, perceptions of dignity, and both current and potential future symptoms, because each of these elements can influence how patients set goals for their health care. Step 2 is particularly important, because data shows that some patients with ICDs do not understand the role the device plays in their health, particularly in terms of care at the end of life.40 The goal is not to overburden patients with decisions, but to determine an overall set of guiding principles by which clinicians can help patients make decisions. These conversations should follow the model of “shared decision making” in which clinicians work together with patients and families to ensure that patients understand, in the context of their illness, the benefits and burdens of a particular treatment and the potential outcomes that may result from its continued use or discontinuation.41

TABLE 35-3 Steps for Communicating with Patients and Families about Goals of Care with CIEDs

| Step | Sample Phrase to Begin Conversation |

|---|---|

| 1. Determine what patients/families know about their illness. | “What do you understand about your health and what is occurring in terms of your illness?” |

| 2. Determine what the patient and family know about the role that the device plays in their health both now and in the future. | “What do you understand the role of the [CIED] to be in your health now? |

| 3. Determine what additional information the patient and family want to know about the patient’s illness. | “What else would be helpful for you to know about your illness or the role the [CIED] plays within it? |

| 4. Correct or clarify any misunderstandings about the current illness and possible outcomes, including the role of the device. | “I think you have a pretty good understanding of what is happening in terms of your health, but there are a few things I would like to clarify with you.” |

| 5. Determine the patient and family’s overall goals of care and desired outcomes. | “Given what we’ve discussed about your health and the potential likely outcomes of your illness, tell me what you want from your health care at this point.” Note: Sometimes patients and families may need more guidance at this point, so some potential guiding language might be: “At this point some patients tell me they want to live as long as possible, regardless of the outcome, whereas other patients tell me that the goal is to be as comfortable as long as possible while also being able to interact with their family. Do you have a sense of what you want at this point?” |

| 6. Using the stated goals as a guide, work to tailor treatments, and in this case the management of the cardiac device, to those goals. | Phrases to be used here depend on the goals as set by the patient and family. For a patient who states that her desired goal is to live as comfortably as possible for whatever remaining time she has left: “Given what you’ve said about assuring that you are as comfortable as possible it might make sense to deactivate the shocking function of your ICD. What do you think about that?” or For a patient who states he wants all life-sustaining treatments to be continued, an appropriate response might be, “In that case, perhaps leaving the antiarrhythmia function of the device active would best be in line with your goals. However, you should understand that this may cause you and your family discomfort at the end of life. We can make a decision at a future point in time about turning the device off. Tell me your thoughts about this.” |

CIEDs, Cardiac implantable electronic devices.

Table adapted from references 1, 35, 38, 48, and 49.

Clinicians must also recognize that while the ultimate power for decision making rests with patients, they may be influenced by factors such as family, culture, or religion. Likewise, although cost should not play a role in the ways that clinicians counsel patients and families, cost does influence the way that some patients make decisions. Studies of patients with serious illness note that many families often lose their savings as well as a major source of income from either the illness itself or from other family members having to care for the patient.41,42 In addition, many of these factors may influence a patient to cede the power of decision making to other individuals.

Benefits/Burdens of Ongoing Device Therapy; Consequences/Uncertainties of Deactivation

Once a patient’s goals of care are determined, knowledge about a specific device, whether pacemaker, ICD, or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) device, is essential to determining how to change its settings consistent with the patients’ goals regarding survival and quality of life. Pacemaker and CRT therapy are indicated for the amelioration of symptoms caused by bradycardia and heart failure, respectively.43 For patients who have no underlying intrinsic rhythm (“pacemaker dependent”), pacing also provides life-sustaining therapy. Pacemaker dependence, however, can vary over time.44 In a pacemaker-dependent patient, death may follow immediately after cessation of pacing therapy. If the patient is not pacemaker dependent, the dying process is unpredictable, and patients need to be assessed closely for symptoms of distress. Deactivation of pacing therapy may result in symptoms that worsen the quality of life (QOL) of a patient who is not pacemaker dependent, but appropriate symptom control in this group can be used effectively to ensure comfort.44 If CRT improves heart failure or reduces arrhythmia burden, discontinuation may impact survival as well as symptoms and QOL. However, ICDs do not improve symptoms, and shocks from an ICD have added to patient and family suffering when the device has fired at the end of life.1,17,28 Deactivation of ICD shock therapy may thus improve QOL in such patients by eliminating the pain and emotional distress associated with the delivery of noxious ICD discharges. Elimination of defibrillation therapy is less likely to result in immediate death unless the patient is experiencing incessant or increasingly frequent ventricular arrhythmias. In addition to deactivation, other options for treatment withdrawal are available. Patients and their surrogates may choose not to replace devices as their generators become depleted.45,46

Supporting Participants in the Decision-Making Process

The Family

Although the ultimate decision regarding treatments rests with the patient (or legal surrogate), conversations about device deactivation optimally occur with the support of the family. Although the primary individuals providing a patient support are generally the partner or blood relative,47 it is important for the health care team to understand the patient’s extended support network, both to help maintain the patient’s overall health and for guidance when the patient can no longer make decisions. In addition to the formal written AD, conversations among members of the health care team, patient, and family in early phases of the patient’s course of disease will help put the entire family “on the same page” in terms of the goals of medical care.48 Health care providers play an important role in supporting the patient’s surrogate and facilitating communication and support of additional family members.

Palliative Care Specialists

Case 10

A 74-year-old man (JE) was admitted to the cardiac care unit in cardiogenic shock. He was intubated, an intra-aortic balloon pump was emergently inserted, and multiple vasoactive agents were started. JE was weaned from the intra-aortic balloon pump 3 days later and extubated 1 week later. However, JE’s condition progressively worsened, with the onset of sepsis and early signs of renal and liver failure. His level of consciousness vacillated between periods of confusion and periods of lucidity. Several family meetings occurred, and working with the palliative care team, a decision was made to stop aggressive treatments. A fentanyl drip was started at 2 mg/hr, and all JE’s vasoactive agents were stopped and ICD therapies deactivated. Within minutes, JE had chest pain, which diminished after he received further fentanyl. His opiate drip was gradually titrated until his chest pain was relieved. JE died 4 hours later.17

Palliative care relieves suffering and improves quality of life for patients with advanced illness and their families. Unlike hospice care, palliative care can be provided simultaneously with appropriate life-prolonging therapies.49 Most U.S. hospitals have some form of a palliative care program.50 Because changing or deactivating device settings can result in gradual worsening of chronic symptoms or onset of new symptoms, it may be helpful to involve palliative care in the care of patients before devices settings are altered, because these concerns can often be eliminated with early symptoms assessment and treatment.

In addition to symptom management, palliative care clinicians are experts at complex conversations surrounding progressive illness. Their involvement in discussions about CIEDs helps to ensure that the patient and family have the opportunity to understand fully the nuances of these decisions and the implications for device management for the patient. Studies show that patients who receive palliative care are more likely to have their treatment wishes followed and have better QOL at the end of life.34 Palliative care also plays a key role in supporting families of patients with advanced disease, who themselves undergo declines in physical and mental health and have an increased risk of death compared with nonfamily controls.51–53

Hospice care is provided to patients with a prognosis of 6 months or less to live who have decided to forgo all treatments aimed at curing their underlying terminal illness.54 Hospice clinicians should be included in conversations for patients as they near the end of life to ensure continuity in implementing the goals of care regarding a CIED. Currently, most hospices do not have practices in place to ensure that these conversations occur at enrollment. Both specialists and generalists must partner with hospices to facilitate these conversations and ensure the availability of clinicians who can deactivate CIEDs for patients near the end of life.

Improving Communication about End-of-Life Care: Importance of Education

To improve communication about device management for patients with advanced disease, educational endeavors need to be instituted for both health care professionals and trainees. Ongoing education for clinicians in practice, including physicians, nurses, social workers, clergy, and device manufacturer representatives, should incorporate teaching about the importance of conversations on device management to improve communication skills and create practice change. Training programs for health care professionals have been shown to improve their knowledge and increase the likelihood they will put new skills into practice.55–57 In addition, fellows and other clinicians in training must also learn the importance of these conversations, as well as undergo training specifically aimed at improving skills in communication. Senior health care providers modeling these conversations for learners are key to improving trainee education about these complex discussions.

Logistics of CIED Deactivation

Logistics of CIED Deactivation

Although the nuances of medical practice require a tailored approach to each patient, HRS recommends that the following series of procedures be consistently applied4:

Deactivation should be performed whenever possible by individuals with EP expertise, such as physicians or device clinic nurses or technicians. In situations where this expertise is not available (see later), deactivation should be performed by medical personnel, such as a hospice physician or nurse, with guidance from IEAPs.58

Since the most urgent need for deactivation of CIEDs is the situation of repetitive ICD shocks, the recent HRS statement on deactivation suggests that, for patients who are diagnosed with a terminal illness, consideration should be given to providing them with a doughnut magnet and that they be given detailed instructions on its use.4 Application of a magnet over ICDs usually will temporarily suspend antitachycardia therapies while not disabling bradycardia pacing functions. However, it should be emphasized that although ICD shocks may be very painful and frightening, they may be lifesaving; therefore, deactivation of the device may not be warranted even in the presence of repetitive shocks, unless the patient has made the decision to forego further device therapies.

Role of Industry-Employed Allied Professional

In many situations, IEAPs may be asked to assist available medical personnel in deactivation when EP expertise is not available. The role of the IEAP is to provide technical assistance to medical personnel,58 who will then perform actual deactivation. Available data from a survey of HRS members and IEAPs suggests that IEAPs perform deactivation 50% of the time,2 the recent HRS statement on deactivation recommends that the IEAP should always act under direct supervision of medical personnel.4 IEAPs experience significant role conflicts when asked to perform clinical functions, in particular device deactivation,59 as illustrated by the following quotes from IEAP interviews59:

Communication with IEAPs by medical personnel at the scene, as well as physicians with EP expertise, needs to include specific instructions regarding features to deactivate, as well as information about the patient’s overall goals. Indeed, once the IEAP has a better understanding of the purpose of changing a device’s settings, the representative may be able to provide suggestions or clarify misperceptions. IEAPs stress this in interviews: “[Clinicians] should not say, ‘Turn off device,’ but they should say, ‘Disable or turn off—discontinue all tachyarrhythmia therapies. …”59

Device Deactivation in the Pediatric Patient

Device Deactivation in the Pediatric Patient

A full discussion of end-of-life issues in minors is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, patients age 24 or under account for 1% to 2% of device implants,60 and it should be recognized that there will be unique situations where quality survival may be unattainable even for a child, and a “good death”61 may be the more appropriate goal. Two major questions may arise when one is considering forgoing life-sustaining treatment for a seriously ill juvenile patient: should the young person be informed about the gravity of his illness? And if so, to what extent should that young person participate in the end-of-life decision? Management of CIEDs in children nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of treatment requires an assessment of the child’s decision-making capacity. Whether or not the child has capacity, communication of decisions should be provided to the child, recognizing developmental level and individual preferences. An ongoing dialogue is required with the juvenile patient, in which his or her concerns are probed and assurance is given that any questions about the illness and its treatment will be answered truthfully. If a child does not have decision-making capacity, a parent or guardian should make decisions in the child’s best interest. (See also Chapter 18.)

Withholding Device Therapy

Withholding Device Therapy

A second, less frequently-discussed ethical aspect of device therapy lies in the decision to withhold this therapy from a patient who may not benefit or in whom benefit is less clear. The ACC/AHA guidelines for device-based therapy clearly state that “recommendations for consideration of ICD therapy, particularly those for primary prevention, apply only to patients who … have a reasonable expectation of survival with a good functional status for more than one year.”43 However, as recently described by Beauregard,62 palliative care experts may be consulted regarding device deactivation in patients with more recent implants. How often this occurs and why are unknown. The question has been raised whether implanting electrophysiologists may ignore severe comorbidities that might limit the benefit of ICDs.62 However, in one reported series of patients requesting deactivation, the three patients diagnosed with malignancy before device implant had all been given life expectancy of longer than 1 year by their oncologist.63 Ethics requires that physicians not impose on patients therapies that may be medically futile, as outlined by the AMA Code of Ethics.8 However, “medical futility” may be difficult to determine. A “reasonable expectation of survival for more than one year,” a relatively “hard” endpoint, can already be difficult to predict in many cases; “reasonable expectation of survival with good functional status” is even more difficult to define.

To prevent the situation of device implantation in individuals who may shortly be requesting deactivation, it is important first for the physician to weigh carefully the ICD benefit in the context of the patient’s overall medical condition. Also, similar to deactivation discussions, discussions about initial implant should also follow patient-centered, “shared decision-making” models.64 Especially in older individuals, discussion of ICD implantation should focus on overall goals of care for a patient’s remaining years.

1 Goldstein NE, Lampert R, Bradley E, et al. Management of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:835-838.

2 Mueller PS, Jenkins SM, Bramstedt KA, Hayes DL. Deactivating implanted cardiac devices in terminally ill patients: practices and attitudes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:560-568.

3 Goldstein N, Bradley E, Zeidman J, et al. Barriers to conversations about deactivation of implantable defibrillators in seriously ill patients: results of a nationwide survey comparing cardiology specialists to primary care physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:371-373.

4 Lampert R, Hayes DL, Annas GJ, et al. Heart Rhythm Society Expert Consensus Statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1008-1026.

5 Beauchamp TL. Principles of biomedical ethics, ed 6. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

6 Annas GJ. The rights of patients: the authoritative ACLU guide to the rights of patients, ed 3. New York: New York University Press; 2004.

7 Snyder L, Leffler C. Ethics manual, fifth edition. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:560-582.

8 American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. AMA 2008–2009. Code of Medical Ethics: current opinions and annotations. Chicago: AMA Press; 2010.

9 Pellegrino ED. Decisions to withdraw life-sustaining treatment: a moral algorithm. JAMA. 2000;283:1065-1067.

10 Rhymes JA, McCullough LB, Luchi RJ, et al. Withdrawing very low-burden interventions in chronically ill patients. JAMA. 2000;283:1061-1063.

11 Quill TE, Barold SS, Sussman BL. Discontinuing an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator as a life-sustaining treatment. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:205-207.

12 In re Quinlan. 70 N.J. 10, 355 A.2d 647 New Jersey Supreme Court. 1976.

13 Cruzan v. Director Missouri Department of Health. 497 U.S. 261 88-1503, 1990.

14 Annas GJ. “Culture of life” politics at the bedside—the case of Terri Schiavo. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1710-1715.

15 Burt RA. Death is that man taking names. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2002.

16 Schneider C. The practice of autonomy: patients, doctors, and medical decisions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

17 Wiegand DL, Kalowes PG. Withdrawal of cardiac medications and devices. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007;18:415-425.

18 Belcherton State School v. Saikewicz. 370 N.E. 2d. 417, 1977.

19 Kay GN, Bittner GT. Should implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and permanent pacemakers in patients with terminal illness be deactivated? Deactivating implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and permanent pacemakers in patients with terminal illness: an ethical distinction. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009;2:336-339.

20 Meisel A, Snyder L, Quill T. American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine End-of-Life Care Consensus: Seven legal barriers to end-of-life care: myths, realities, and grains of truth. JAMA. 2000;284:2495-2501.

21 Vacco v. Quill. 521 U.S. 793, 95-1858. Supreme Court of the United States, 1997.

22 Washington v. Glucksberg. 521 U.S. 702, 96-110. Supreme Court of the United States, 1997.

23 Sulmasy DP. Within you/without you: biotechnology, ontology, and ethics. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;1:69-72.

24 Zellner RA, Aulisio MP, Lewis WR. Deactivating permanent pacemakers in patients with terminal illness; patient autonomy is paramount. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009;2:340-344.

25 Swetz KM, Crowley ME, Hook C, Mueller PS. Report of 255 clinical ethics consultations and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:686-691.

26 The Joint Commission. Joint Commission Requirements, 2010.

27 PSDA-90. Ominbus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. [Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990]. Pub. L. 101–508, 4206, and 4751. (Medicare and Medicaid, respectively), 42 U.S.C. 1395cc(a) (I)(Q), 1395 mm (c) (8), 1395cc(f), 1396(a)(57), 1396a(a) (58), and 1396a(w) (Suppl 1991). U S, 2010.

28 Braun TC, Hagen NA, Hatfield RE, Wyse DG. Cardiac pacemakers and implantable defibrillators in terminal care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:126-131.

29 AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Physician objection to treatment and individual patient discrimination: CEJA Report 6-A-07. Chicago: AMA Press; 2007.

30 May T. Bioethics in a liberal society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002.

31 Goldstein NE, Mehta D, Teitelbaum E, et al. “It’s like crossing a bridge”: complexities preventing physicians from discussing deactivation of implantable defibrillators at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;1:2-6.

32 Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061-1066.

33 Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:890-895.

34 Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

35 Lewis WR, Luebke DL, Johnson NJ, et al. Withdrawing implantable defibrillator shock therapy in terminally ill patients. Am J Med. 2006;119:892-896.

36 Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163-181.

37 Nicolasora N, Pannala R, Mountantonakis S, et al. If asked, hospitalized patients will choose whether to receive life-sustaining therapies. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:161-167.

38 Fried TR, O’Leary JR. Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient- and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1602-1607.

39 Berger JT, Gorski M, Cohen T. Advance health planning and treatment preferences among recipients of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: an exploratory study. J Clin Ethics. 2006;17:72-78.

40 Goldstein NE, Mehta D, Siddiqui S, et al. “That’s like an act of suicide”: patients’ attitudes toward deactivation of implantable defibrillators. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;1:7-12.

41 Goldstein NE, Back AL, Morrison RS. Titrating guidance: a model to guide physicians in assisting patients and family members who are facing complex decisions. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1733-1739.

42 Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272:1839-1844.

43 Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices): developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2008;117:e350-e408.

44 Schoenfeld MH. Follow-up assessments of the pacemaker patient. In: Ellenbogen KA, Wood MA, editors. Cardiac pacing and ICDs. ed 5. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008:498-545.

45 Schoenfeld MH. Deciding against defibrillator replacement: second-guessing the past? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:2019-2021.

46 Wilkoff BL, Auricchio A, Brugada J, et al. Heart Rhythm Society, European Heart Rhythm Association, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association, Heart Failure Society of America. HRS/EHRA expert consensus on the monitoring of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs): description of techniques, indications, personnel, frequency and ethical considerations. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:907-925.

47 Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, et al. Assistance from family members, friends, paid care givers, and volunteers in the care of terminally ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:956-963.

48 Lynn J, Goldstein NE. Advance care planning for fatal chronic illness: avoiding commonplace errors and unwarranted suffering. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:812-818.

49 Morrison RS, Meier DE. Clinical practice: palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2582-2590.

50 Goldsmith B, Dietrich J, Du Q, Morrison RS. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1094-1102.

51 Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215-2219.

52 Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, et al. Health effects of caregiving: the Caregiver Health Effects Study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:110-116.

53 Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: a prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:113-119.

54 National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 2009.

55 Ersek M, Grant MM, Kraybill BM. Enhancing end-of-life care in nursing homes: Palliative Care Educational Resource Team (PERT) program. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:556-566.

56 Robinson K, Sutton S, von Gunten CF, et al. Assessment of the Education for Physicians on End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Project. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:637-645.

57 Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Treatment IIIM-PAtC. JAMA. 2002;288:2836-2845.

58 Lindsay BD, Estes NA3rd, Maloney JD, et al. Heart Rhythm Society policy statement update: recommendations on the role of industry-employed allied professionals (IEAPs). Heart Rhythm. 5, 2008.

59 Mueller PS, Ottenberg AL, Hayes DL. Role conflicts among industry employed allied professionals: characteristics and recommendations for addressing them. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:S11.

60 Zhan C, Baine WB, Sedrakyan A, Steiner C. Cardiac device implantation in the United States from 1997 through 2004: a population-based analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;1:13-19.

61 Baines P. Medical ethics for children: applying the four principles to paediatrics. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:141-145.

62 Beauregard L. Ethics in electrophysiology: a complaint from palliative care. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:226-267.

63 Kobza R, Erne P. End-of-life decisions in patients with malignant tumors. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:845-849.

64 Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1087-1110.