Ovarian and Uterine Events

The menstrual cycle consists of a coordinated series of ovarian and uterine events. In the ovary, the following sequence occurs: (1) several ovarian follicles ripen; (2) one of the ripe follicles ruptures, causing ovulation; (3) the ruptured follicle evolves into a corpus luteum; and (4) if fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum atrophies. As these ovarian events are taking place, parallel events take place in the uterus: (1) while ovarian follicles ripen, the endometrium prepares for nidation (implantation of a fertilized ovum) by increasing in thickness and vascularity; (2) after ovulation, the uterus continues its preparation by increasing secretory activity; and (3) if implantation fails to occur, the thickened endometrium breaks down, causing menstruation, and the cycle begins anew.

The Roles of Estrogens and Progesterone

The uterine changes that occur during the cycle are brought about under the influence of estrogens and progesterone produced by the ovaries. During the first half of the cycle, estrogens are secreted by the maturing ovarian follicles. As suggested by Fig. 48.1, these estrogens act on the uterus to cause proliferation of the endometrium. At midcycle, one of the ovarian follicles ruptures and then evolves into a corpus luteum. For most of the second half of the cycle, estrogens and progesterone are produced by the newly formed corpus luteum. These hormones maintain the endometrium in its hypertrophied state. At the end of the cycle, the corpus luteum atrophies, causing production of estrogens and progesterone to decline. In response to the diminished supply of ovarian hormones, the endometrium breaks down.

The Role of Pituitary Hormones

Two anterior pituitary hormones—follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)—play central roles in regulating the menstrual cycle. Precisely timed alterations in the secretion of these hormones are responsible for coordinating the structural and secretory changes that occur throughout the menstrual cycle. During the first half of the cycle, FSH acts on the developing ovarian follicles, causing them to mature and secrete estrogens. The resultant rise in estrogen levels exerts a negative feedback influence on the pituitary, thereby suppressing further FSH release. At midcycle, LH levels rise abruptly (see Fig. 48.1). This LH surge causes the dominant follicle to swell rapidly, burst, and release its ovum. After ovulation, the ruptured follicle becomes a corpus luteum and, under the influence of LH, begins to secrete progesterone.

Estrogens

Biosynthesis and Elimination

Females

In premenopausal women, the ovary is the principal source of estrogen. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, estrogens are synthesized by ovarian follicles; during the luteal phase, estrogens are synthesized by the corpus luteum. The major estrogen produced by the ovaries is estradiol. In the periphery, some of the estradiol secreted by the ovaries is converted into estrone and estriol, hormones that are less potent than estradiol itself. Estrogens are eliminated by a combination of hepatic metabolism and urinary excretion.

During pregnancy, large quantities of estrogens are produced by the placenta. Excretion of these hormones results in high levels of estrogens in the urine.

Males

Estrogen production is not limited to females. In the human male, small amounts of testosterone are converted into estradiol and estrone by the testes. Enzymatic conversion of testosterone in peripheral tissues (e.g., liver, fat, skeletal muscle) results in additional estrogen production.

Mechanism of Action

Like other steroidal hormones (e.g., testosterone, cortisol), estrogen acts primarily through receptors in the cell nucleus, not on the cell surface. Hence, to produce its effects, estrogen must diffuse into cells, migrate to the nucleus, and then bind with an estrogen receptor (ER). The estrogen-ER complex then binds with an estrogen response element on a target gene, altering the rate of gene transcription. It is important to note that not all ERs are found in the nucleus: some ERs are found on cell membranes. Activating these surface receptors produces a rapid response—more rapid than can be produced by activating nuclear receptors.

There are two forms of ERs, termed ER alpha and ER beta. ER alpha is highly expressed in the vagina, uterus, ovaries, mammary glands, vascular epithelium, and hypothalamus. ER beta is expressed in the ovary and prostate and to a lesser extent in the lungs, brain, bones, and blood vessels. Some cells have both types of ER receptor.

Physiologic and Pharmacologic Effects

Effects on Primary and Secondary Sex Characteristics of Females

Estrogens support the development and maintenance of the female reproductive tract and secondary sex characteristics. These hormones are required for the growth and maturation of the uterus, vagina, fallopian tubes, and breasts. In addition, estrogens direct pigmentation of the nipples and genitalia.

Estrogens have a profound influence on physiologic processes related to reproduction. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, estrogens promote (1) ductal growth in the breast, (2) thickening and cornification of the vaginal epithelium, (3) proliferation of the uterine epithelium, and (4) copious secretion of thickened mucus from endocervical glands. In addition, estrogens increase vaginal acidity (by promoting local deposition of glycogen, which is then acted on by lactobacilli and corynebacteria to produce lactic acid). At the end of the menstrual cycle, a decline in estrogen levels can bring on menstruation. However, it is the fall in progesterone levels at the end of the cycle that normally causes breakdown of the endometrium and resultant menstrual bleeding. After menstruation, estrogens promote endometrial restoration.

During pregnancy, the placenta produces estrogen in large amounts. This estrogen stimulates uterine blood flow and growth of uterine muscle. In addition, it acts on the breast to continue ductal proliferation. However, final transformation of the breast for milk production requires the combined influence of estrogen, progesterone, and human placental lactogen.

Metabolic Actions

Endogenous estrogens affect various nonreproductive tissues. Important among these are bone, cardiovascular, and central nervous system (CNS). They also have an important roles glucose homeostasis.

Bone

Estrogens have a positive effect on bone mass. Under normal conditions, bone undergoes continuous remodeling, a process in which bone mineral is resorbed and deposited in equal amounts. The principal effect of estrogens on the process is to block bone resorption, although estrogens may also promote mineral deposition.

During puberty, the long bones grow rapidly under the combined influence of growth hormone, adrenal androgens, and low levels of ovarian estrogens. When estrogen levels grow high enough, they promote epiphyseal closure and thereby bring linear growth to a stop.

Cardiovascular Effects

Cardiovascular disease is much less common in premenopausal women. Estrogens have several roles in lowering this risk. For example, estrogen receptors in the vascular smooth muscle respond to activation by decreasing vasoconstriction. Activation of estrogen receptors in vessel endothelium results in the production of nitric oxide, which results in vasodilation and increased perfusion. Estrogens also decrease atherosclerosis through favorable effects on cholesterol levels: levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol are reduced, whereas levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol are elevated.

Blood Coagulation

Estrogens both promote and suppress blood coagulation. Estrogens promote coagulation by (1) increasing levels of coagulation factors (e.g., factors II, VII, IX, X, and XII), and (2) decreasing levels of factors that suppress coagulation (e.g., antithrombin). Estrogens suppress coagulation by increasing the activity of factors that promote breakdown of fibrin, a protein that reinforces blood clots. The net effect—increased or decreased coagulation—may be determined by a hereditary defect in one of these targets.

Central Nervous System

In the CNS, estrogens have a neuroprotective effect by defending neurons from the effects of oxidative stress and injury. They also have a role in neuronal growth and repair through stimulation of nerve growth factors. Estrogen-induced synaptic changes, coupled with estrogen-promoted increases in synaptic serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, are thought to preserve cognitive function, enhance short-term memory, and regulate mood. Cerebral perfusion is also enhanced by the release of nitric acid and the resulting vasodilation.

Glucose Homeostasis

Estrogens play an active role in maintaining glucose levels. In conditions that lead to insulin resistance due to impaired transport, estrogen has been shown to increase insulin sensitivity to promote glucose uptake. Estrogens also have a role in insulin secretion and are believed to protect pancreatic islet beta cells from certain types of injury.

Physiologic Alterations Accompanying Menopause

Menopause may occur as the result of surgery (i.e., surgical menopause associated with bilateral oophorectomy) or as the result of declining ovarian function associated with aging. Natural menopause typically begins at about age 51 to 52 years, with 95% of women entering menopause between the ages of 45 and 55 years. During the initial phase, the menstrual cycle becomes irregular, anovulatory cycles may occur, and periods of amenorrhea may alternate with menses. Eventually, ovulation and menstruation cease entirely. Production of ovarian estrogens decreases gradually, coming to a complete stop several years after menstruation has ceased.

Loss of estrogen has multiple effects. Prominent symptoms experienced by the patient include vasomotor symptoms, sleep disturbances, and urogenital atrophy. Additional physiologic changes include bone loss and altered lipid metabolism.

Vasomotor Symptoms

Vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) develop in about 70% of postmenopausal women. Episodes are characterized by sudden skin flushing, sweating, and a sensation of uncomfortable warmth. These episodes can occur at night, resulting in drenching sweats. Severe episodes can cause sleep disturbances, fatigue, and irritability. In most women, hot flashes abate within several months to a few years; in others, they may persist for a decade or more.

Urogenital Atrophy

Of all structures in the body, the urethra and vagina have the highest concentrations of estrogen receptors. Activation of these receptors maintains the functional integrity of the urethra and vaginal epithelium. Hence, when estrogen levels decline during menopause, these structures undergo degenerative change. Atrophy of the urethra causes urge incontinence and urinary frequency. Urethritis and urinary tract infections can also occur. Atrophy of the vaginal epithelium can lead to dryness and pain with intercourse. In addition, alterations in vaginal secretions result in decreased acidity, which can allow the growth of pathogenic bacteria, resulting in vaginal infections.

Mental Changes

Many women report cognitive changes such as difficulty in problem solving and short-term memory loss around the time when menopause begins. Others experience depression or an increase in anxiety. These, also, tended to occur during the time of transition and often compounded sleep disturbances.

Bone Loss

In the absence of estrogen, bone resorption accelerates, leading to a 12% loss of bone density shortly after menopause. Osteoporosis is characterized by bone demineralization, altered bone architecture, and reduced bone strength. Compression fractures of the vertebrae are common and can decrease height and produce a hump. In osteoporotic women, fractures of the hip and wrist can result from minimal trauma.

Altered Lipid Metabolism

Studies have demonstrated slight, but significant, increases in LDL cholesterol with concomitant decreases in HDL cholesterol. These are thought to have a role in the increase in cardiovascular disease that increases after menopause.

Clinical Pharmacology

Now that we have reviewed the effects of endogenous estrogens, let’s examine how estrogen preparations are used clinically. We’ll begin with a discussion of how these drugs are used.

Therapeutic Uses

Estrogens have contraceptive and noncontraceptive applications. In this chapter, discussion is limited to the noncontraceptive applications. Use of estrogens for contraception is discussed in Chapter 49.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women is the most common noncontraceptive use of estrogens. When estrogen is used for this purpose, it is usually accompanied by the use of progestins. For this reason, we will cover hormone therapy after the discussion of progestins.

Female Hypogonadism

In the absence of ovarian estrogens, pubertal transformation will not take place. Causes of estrogen deficiency include primary ovarian failure, hypopituitarism, bilateral oophorectomy (removal of both ovaries), and Turner syndrome (a genetic disorder that impairs gonadal function). In girls with estrogen insufficiency, puberty can be induced by giving exogenous estrogens. This treatment promotes breast development, maturation of the reproductive organs, and development of pubic and axillary hair. To simulate normal patterns of estrogen secretion, the regimen should consist of continuous low-dose therapy (for about a year) followed by cyclic administration of estrogen in higher doses. Estrogen therapy for these conditions is typically managed by specialists.

Acne

Estrogens, in the form of oral contraceptives, can help control acne. Treatment is limited to patients at least 14 or 15 years old who want contraception. Use of estrogen for acne is discussed in Chapter 85.

Cancer Palliation

Estrogens are sometimes used for palliative therapy in management of advanced prostate cancer in men and in a select type of metastatic breast cancer in both men and women. This use is directed by an oncologist or other specialist in this field.

Adverse Effects

The principal concerns with estrogen therapy are the potential for endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, and cardiovascular thromboembolic events. Of these, the potential for endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer can be resolved by prescribing a progestin, if indicated.

Estrogens have been associated with gallbladder disease, jaundice, and headache. Use during menopause may produce or uncover gallbladder disease. Jaundice may develop in women with preexisting liver dysfunction, especially those who experienced cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy. Estrogens can increase the risk for headache, especially migraine.

Nausea is the most frequent undesired response to the estrogens. Fortunately, nausea diminishes with continued use and is rarely so severe as to necessitate treatment cessation. Fluid retention with edema commonly occurs. Most other adverse effects are more of a nuisance (e.g., chloasma, a patchy brown facial discoloration) than a concern.

Contraindications

Estrogens should not be taken by patients with a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolus, or conditions such as stroke or myocardial infarction (MI) that occurred secondary to a thromboembolic event. They should not be prescribed to women who are pregnant or who have vaginal bleeding without a known cause. Patients with a history of liver disease, estrogen-dependent tumors, or breast cancer (except when indicated for management) also should not take estrogens.

Interactions

Estrogens are major substrates of CYP1A2 and CYP3A4. Inducers of these isoenzymes may lower estrogen levels, whereas drugs that are inhibitors may raise estrogen levels. Additionally, they may decrease the effectiveness of some antidiabetic drugs and thyroid preparations. Estrogens can also interact with anticoagulants and other drugs that affect clotting.

Preparations and Routes of Administration

Estrogen is available in conjugated and esterified forms. Esterified estrogens are plant based; conjugated estrogens are natural preparations derived from the urine of pregnant horses. Until mid-2016 synthetic conjugated estrogens A [Cenestin] and B [Enjuvia] were available; however, the manufacturer has withdrawn them from the market. At the time of this writing, there is no generic substitution for these synthetic conjugated estrogens.

Oral

Owing to convenience, the oral route is used more than any other. The most active estrogenic compound—estradiol—is available alone and in combination with progestins.

Transdermal

Transdermal estradiol is available in four formulations:

• Gels [EstroGel, Elestrin, Divigel]

• Patches [Alora, Climara, Estraderm, Menostar, Vivelle-Dot, Oesclim  ]

]

Application is specific to certain body regions. The emulsion is applied once daily to the top of both thighs and the back of both calves. The spray is applied once daily to the forearm. The gel is applied once daily to one arm, from the shoulder to the wrist or to the thigh (Divigel). The patches are applied to the skin of the trunk (but not the breasts). Rates of estrogen absorption with transdermal formulations range from 14 to 60 mcg/24 hr, depending on the product employed.

Compared with oral formulations, the transdermal formulations have four advantages:

Intravaginal

Estrogens for intravaginal administration are available as tablets, creams, and vaginal rings. The tablets [Vagifem], creams [Estrace Vaginal, Premarin Vaginal], and one of the two available vaginal rings [Estring] are used only for local effects, primarily treatment of vulval and vaginal atrophy associated with menopause. The other vaginal ring [Femring] is used for systemic effects (e.g., control of hot flashes and night sweats) as well as local effects (e.g., treatment of vulval and vaginal atrophy).

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are drugs that activate estrogen receptors in some tissues and block them in others. These drugs were developed in an effort to provide the benefits of estrogen (e.g., protection against osteoporosis, maintenance of the urogenital tract, reduction of LDL cholesterol) while avoiding its drawbacks (e.g., promotion of breast cancer, uterine cancer, and thromboembolism). Four SERMs are available: tamoxifen [Nolvadex-D], toremifene [Fareston], raloxifene [Evista], and bazedoxifene [Duavee]. None of these offers all of the benefits of estrogen, and none avoids all of the drawbacks.

Tamoxifen was the first SERM to be widely used. By blocking estrogen receptors, tamoxifen (and its active metabolite, endoxifen) can inhibit cell growth in the breast. As a result, the drug is used extensively to prevent and treat breast cancer. Unfortunately, blockade of estrogen receptors also produces hot flashes. By activating estrogen receptors, tamoxifen protects against osteoporosis and has a favorable effect on serum lipids. However, receptor activation also increases the risk for endometrial cancer and thromboembolism. The pharmacology of tamoxifen and toremifene (a close relative of tamoxifen) is discussed in Chapter 82.

Raloxifene is very similar to tamoxifen. The principal difference is that raloxifene does not activate estrogen receptors in the endometrium and hence does not pose a risk for uterine cancer. Like tamoxifen, raloxifene protects against breast cancer and osteoporosis, promotes thromboembolism, and induces hot flashes. Raloxifene is approved only for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk women. Raloxifene is discussed at length in Chapter 59.

In 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Duavee (conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene) for prevention of vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus. Duavee is the first drug to combine estrogen with an estrogen agonist/antagonist (bazedoxifene). The bazedoxifene component of Duavee reduces the risk for excessive growth of the lining of the uterus that can occur with the estrogen component. Contraindications to taking Duavee are the same as for other estrogen-containing products.

Progestins

Estrogens and progestins are often prescribed together. Before we discuss these uses, it will be helpful to discuss progesterone. As previously mentioned, progesterone is the principal endogenous progestational hormone. As its name implies, progesterone acts before gestation to prepare the uterus for implantation of a fertilized ovum. In addition, progesterone helps maintain the uterus throughout pregnancy.

Biosynthesis

Progesterone is produced by the ovaries and the placenta. Ovarian production occurs during the second half of the menstrual cycle. During this period, progesterone is synthesized by the corpus luteum, in response to LH released from the anterior pituitary. If implantation of a fertilized ovum does not occur, progesterone production by the corpus luteum ceases, and menstrual flow begins. However, if implantation does take place, the developing trophoblast will produce its own luteotropic hormone—human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)—that will stimulate the corpus luteum to continue making progesterone. For the first 7 weeks of gestation, the placenta depends entirely on progesterone from the corpus luteum. However, between weeks 7 and 10, production of progesterone is shared between the corpus luteum and placenta. After 10 weeks of gestation, progesterone made by the placenta is sufficient to support pregnancy, and hence ovarian progesterone production declines. Placental synthesis of progesterone and estrogen continues throughout the pregnancy.

Mechanism of Action

As with estrogen, receptors for progesterone are found in the cell nucleus. Hence, to produce an effect, progesterone must diffuse across the cell membrane, migrate to the nucleus, and then bind with a progesterone receptor (PR). The progesterone-PR complex then binds with a progesterone regulatory element on a target gene, thereby rapidly increasing gene transcription. As with estrogen, there are two types of receptors for progesterone, designated PR-A and PR-B. In general, the stimulatory actions of progesterone are mediated by PR-B, whereas inhibitory actions are mediated by PR-A.

Physiologic Effects

Effects During the Menstrual Cycle

Progesterone is secreted during the second half of the menstrual cycle from a proliferative state into a secretory state. If implantation does not occur, progesterone production by the corpus luteum declines. The resultant fall in progesterone levels is the principal stimulus for the onset of menstruation.

In addition to affecting the endometrium, progesterone affects the endocervical glands, breasts, body temperature, respiration, and mood. Under the influence of progesterone, secretions from endocervical glands become scant and viscous. (In contrast, estrogen makes these secretions profuse and watery.) In addition, progesterone causes the epithelium of the breast to divide and grow. Actions in the CNS may cause depression and sleepiness. By increasing the sensitivity of the respiratory center to CO2, progesterone causes the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) in blood to fall. At midcycle, when ovulation occurs, progesterone raises body temperature by 0.6° C (1° F).

Effects During Pregnancy

As noted, progesterone levels increase during pregnancy. These high levels suppress contraction of uterine smooth muscle and thereby help sustain pregnancy. Unfortunately, progesterone also suppresses contraction of GI smooth muscle, which leads to prolonged transit time and constipation. In the breast, progesterone promotes growth and proliferation of alveolar tubules (acini), the structures that produce milk. Metabolic effects include suppression of arterial PCO2, altered serum bicarbonate content, and elevation of serum pH. Lastly, progesterone may help suppress the maternal immune system, thereby preventing immune attack on the fetus.

Clinical Pharmacology

Now that we have reviewed the effects of endogenous progesterone, let’s examine how progestins are used clinically. We’ll begin with a discussion of therapeutic uses.

Therapeutic Uses

Discussion in this chapter is limited to the noncontraceptive uses of progestins. Use for contraception is considered in Chapter 49.

Menopausal Hormone Therapy

The primary noncontraceptive use of progestins is to counteract the adverse effects of estrogen on the endometrium in women undergoing menopausal hormone therapy (HT). This application is discussed later.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

This condition, characterized by heavy irregular bleeding, occurs when progesterone levels are insufficient to balance the stimulatory influence of estrogen on the endometrium. In the absence of sufficient progesterone, estrogen puts the endometrium in a state of continuous proliferation. Because progesterone is unavailable to induce monthly endometrial breakdown, the excessively proliferative endometrium undergoes spontaneous sloughing at irregular intervals. The result is periodic episodes of severe bleeding.

Treatment has two objectives: the initial goal is cessation of hemorrhage; the long-term goal is to establish a regular monthly cycle. Excessive bleeding can be stopped by administering a progestin for 10 to 14 days. When dosing is stopped, withdrawal bleeding takes place. Bleeding is likely to be profuse and associated with cramping. Giving an oral contraceptive twice daily for 5 to 7 days can help stabilize the endometrium and thereby reduce bleeding duration.

Cyclic therapy is employed to establish a regular monthly cycle. In one regimen, oral dosing is started 10 to 14 days after the onset of each menstrual period and continued for the next 10 days. Alternatively, a progestin can be given for the first 10 days of each month. Both approaches can promote regular endometrial breakdown and menstruation.

Amenorrhea

Progestins can induce menstrual flow in selected women who are experiencing amenorrhea. If endogenous estrogen levels are adequate, treatment with a progestin for 5 to 10 days will be followed by withdrawal bleeding when the progestin is stopped. If estrogen levels are low, it may be necessary to induce endometrial proliferation with an estrogen before giving the progestin.

Endometrial Carcinoma and Hyperplasia

Progestins can provide palliation in women with metastatic endometrial carcinoma, but these drugs do not prolong life. Several months of treatment may be required for a response. Management is by specialists.

Endometrial hyperplasia, a potentially precancerous condition, can be suppressed with progestins. Benefits derive from counteracting the proliferative effects of estrogen. Treatment options include oral therapy with megestrol acetate [Megace] or medroxyprogesterone acetate [Provera] and local delivery of a levonorgestrel using the Mirena IUD.

Other Uses

Progestins are used to support an early pregnancy in women with corpus luteum deficiency syndrome and in women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF). One progestin—hydroxyprogesterone acetate [Makena]—is approved for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of preterm delivery.

Adverse Effects

Up to 20% of patients may experience breast tenderness, headache, abdominal discomfort, arthralgias, and depression. When used continuously for birth control, progestins greatly decrease production of cervical mucus and cause involution of the endometrial layer. Effects on the endometrium lead to spotting, breakthrough bleeding, and irregular menses. Progestins, in combination with estrogen, increase the risk for breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Preparations and Routes of Administration

Progestins are available in oral, IM, subcutaneous (subQ), intravaginal, intrauterine, and transdermal formulations. Older oral progestins include medroxyprogesterone acetate [Provera], norethindrone [Micronor, Nor-QD, others], norethindrone acetate [Aygestin], megestrol acetate [Megace], levonorgestrel [Plan B One-Step, Next Choice], and a micronized formulation of progesterone [Prometrium]. Newer oral progestins—norgestimate and drospirenone—are available in fixed-dose combinations with estradiol sold as Prefest and Angeliq, respectively. Intramuscular progestins are medroxyprogesterone acetate [Depo-Provera] and progesterone (in oil). Medroxyprogesterone acetate is also available in a formulation for subQ injection [Depo-SubQ Provera 104]. Micronized progesterone for intravaginal use is available as progesterone gel [Crinone] and a vaginal insert [Endometrin]. Transdermal products are limited to norethindrone (formulated with estradiol under the name CombiPatch) and levonorgestrel (formulated with estradiol under the name ClimaraPro). A second-generation progestin—etonogestrel—used for contraception is available by itself as a subQ implant [Nexplanon] and combined with estradiol in a vaginal ring [NuvaRing].

Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Menopausal HT, formerly known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), consists of low doses of estrogen (with or without a progestin) taken to compensate for the loss of estrogen that occurs during menopause. There are two basic regimens for HT: estrogen alone (ET) and estrogen plus a progestin (estrogen/progestin therapy [EPT]). The purpose of estrogen in both regimens is to control menopausal symptoms by replacing estrogen that was lost owing to menopause. The progestin is present for one reason only: to counterbalance estrogen-mediated stimulation of the endometrium, which can lead to endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. (Progestins should not be prescribed for women who have undergone hysterectomy.)

It is typically the vasomotor symptoms that compel most women to seek HT. Hot flashes and the drenching sweats that accompany them can interfere with daily life and cause sleepless nights. Not only are they uncomfortable, but they also may create embarrassing situations, especially for women working with the public when appearances can be important. When vasomotor symptoms are severe, HT can be truly life changing.

Women who take HT often report an improved quality of life as well. In addition to controlling vasomotor symptoms, they report improved sleep, restoration of libido, improved cognition, and enhanced mood. Although there have been insufficient studies to quantify quality-of-life issues, the anecdotal evidence supports this as an added benefit.

From the medical perspective, HT confers three primary benefits: suppression of vasomotor symptoms, prevention of urogenital atrophy, and prevention of osteoporosis and related fractures. For all three, treatment is highly effective. (Unfortunately, the benefits of urogenital atrophy and osteoporosis prevention are not sustained and will decline after HT is withdrawn.)

Given the positive physiologic effects of estrogen and the detrimental physiologic changes that occur with estrogen loss, it might seem logical to prescribe HT for all women experiencing menopause. Indeed, this was once common practice with therapy that began during perimenopause and continued into later years of life. Then, in the early 2000s, data from two landmark studies, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study and its follow-up (HERS and HERS II), demonstrated that, contrary to popular assumptions, use of HT could increase, rather than prevent, cardiovascular events. Women taking HT in the study also had an increase in thromboembolic events such as DVT and stroke. For women receiving EPT (but not ET), there was a significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer. The reaction in the medical community was strong and swift as many providers stopped prescribing HT altogether and use of HT declined by 80%.

More recently, increased scrutiny of these early studies yielded concerns that have resulted in a reexamination of these risks. Subjects in those studies tended to be older. For example, only 3.5% of women in the WHI study were in the 50- to 54-year age range, which is the age at which most women currently begin HT. Further, the therapy in those studies was at a higher dose, and use was prolonged beyond that of recommended current practice. When WHI data for women aged 50 to 59 years taking HT for less than 10 years were examined, it was discovered that the increase in venous thromboembolic episodes was only between 1.1 to 5 out of 1000 women taking ET and 5.1 to 10 out of 1000 women taking EPT. For women taking ET, there was no increase in coronary heart disease (CHD), and for women taking EPT, CHD increase was 1.1 to 5 out of 1000 women, and venothrombotic episode increase was 5.1 to 10 out of 1000 women. Moreover, when benefits were examined, for both ET and EPT, 5.1 to 10 out of 1000 women experienced a reduction in overall mortality compared with women not taking HT.

Subsequent and ongoing research has provided more insight into the relationships of HT to dosage, time of initiation, length of use, and patient age, which were not adequately accounted for in the original reports from these studies. The more informed view of HT has evolved to a more reasoned approach to HT.

Benefits and Risks of Hormone Therapy

As with any drug, prescribing decisions require weighing the benefits and risks. It is important to keep in mind that our understanding of the benefits and risks of HT continues to evolve as current research focuses on the new demographic of younger woman taking HT at lower doses over fewer years.

Recognizing that findings based on women older than 60 years taking high-dose, long-term HT for more than a decade could not be generalized to younger women taking low-dose HT for shorter time intervals, The Endocrine Society undertook an extensive review of published research to determine the benefits and risk of HT in women recently menopausal (i.e., less than 10 years postmenopausal) and aged 50 to 59. Significant findings are summarized in Table 48.1. Not included in the table are results of benefits related to the vasomotor and urogenital symptoms because the benefit (90% reduction in symptoms) is firmly established. Also not included are many of the previously assumed risks that were not supported in the data.

TABLE 48.1

Benefits and Risks of Menopausal Hormone Therapy

| Benefits Over 5 Years | Number of Fewer Cases Per 1000 Women Aged 50–59 Years | |

| Estrogen + Progestin (EPT) | Estrogen Only (ET) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.9 | 3.8 |

| Osteoporotic fractures | 4.9 | 5.9 |

| Breast cancer | — | 1.5 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.2 | — |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 11 | 11 |

| Mortality for all causes | 5.3 fewer deaths | 5 fewer deaths |

| Risk Over 5 Years | Number of Increased Cases Per 1000 Women Aged 50–59 Years | |

| Estrogen + Progestin (EPT) | Estrogen Only (ET) | |

| Thromboembolism | 5 | 2 |

| Stroke | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Breast cancer | 6.8 | — |

| Cholecystitis* | 9.6 | 14.2 |

Based on these findings, especially considering the benefits of overall mortality, it certainly seems unreasonable to refuse HT for younger women desiring it once individual risks are assessed. Unfortunately, this does not address concerns of older women who have indications for therapy. More studies are needed; however, in the meantime, it is important to recognize that risk for complications increases with age. Further, research findings suggest that use of HT in women older than 65 years may increase the risk for dementia.

Recommendations on Hormone Therapy Use

When making decisions regarding whether or not to prescribe HT, risk factors for the individual must be inventoried, and the hoped-for benefits should be clearly defined. For women with significant baseline risks (e.g., personal or family history of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease), the risk for harm from HT goes up.

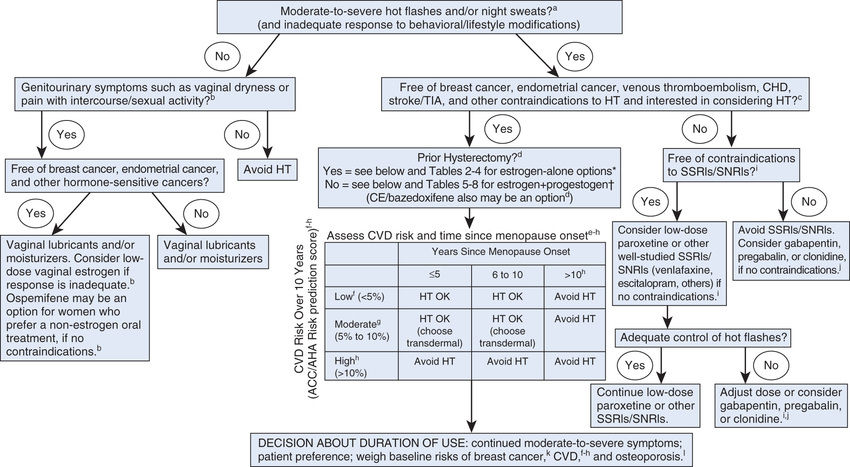

Recently, several expert sources have issued revised recommendations on HT. The recommendations that follow represent a composite of those offered by four groups: the North American Menopause Society, The Endocrine Society, the FDA, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Fig. 48.2 provides additional guidance.

General Recommendations

To balance benefits and risks, an individual risk profile should be compiled for every woman considering HT. All candidates for HT should be informed of known risks. Women with multiple risk factors should consider alternative therapies. For most women, the benefits of long-term HT for disease prevention do not outweigh the risks and hence long-term HT should generally be avoided. Conversely, the benefits of short-term therapy (less than 5 years) to treat menopausal symptoms often do justify the risks. To keep risk as low as possible, HT should be used in the lowest dosage and for the shortest time needed to accomplish treatment goals.

Use for Approved Indications

Hormone therapy has only three approved indications:

• Treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause

• Treatment of moderate to severe symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy associated with menopause

Hormone therapy should be restricted to achieving one or more of these goals. With the first two indications, duration of treatment is relatively short (typically 3–4 years), and hence the risk for harm is relatively low—except for women with established heart disease. In contrast, prevention of osteoporosis requires lifelong HT, and hence the risk for harm is higher.

The only indication for long-term progestin therapy is protection against endometrial cancer, which could be caused by unopposed estrogen. Accordingly, use of EPT should be limited to women with an intact uterus. For women who have had a hysterectomy, estrogen alone should be used.

Treatment of Vasomotor Symptoms

Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats). To increase safety, the lowest effective dosage should be employed. Furthermore, because vasomotor symptoms subside over time, the need for continued HT should be reassessed at regular intervals.

For women determined to be at too high risk for HT, other options are available, but they are less effective than estrogen. Trials have shown that two antidepressants—escitalopram [Lexapro] and desvenlafaxine [Pristiq]—can produce a modest but meaningful reduction in both the frequency and severity of hot flashes. Escitalopram is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI); desvenlafaxine is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). Other SSRIs and SNRIs are likely to be effective as well. Paroxetine [Brisdelle], an SSRI, was approved in 2013 for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in menopause. Paroxetine is used as an antidepressant and is discussed further in Chapter 25.

By contrast, controlled trials have shown that soy isoflavones do not reduce hot flashes. In fact, these preparations may make symptoms worse.

Treatment of Symptoms of Vulvar and Vaginal Atrophy

Estrogen is the most effective treatment for reducing symptoms of menopause-related vulvar and vaginal atrophy, characterized by dryness, irritation, and uncomfortable intercourse. Because systemic estrogen carries significant risks, the FDA recommends that, if HT is being used solely to manage vulvar and vaginal symptoms, a topical estrogen formulation should be considered. Options include vaginal creams, vaginal tablets, and vaginal rings (Table 48.2). Although long-term data are lacking, it seems likely that topical estrogen is safer than oral estrogen because, with nearly all topical formulations, blood levels of estrogen remain low. The notable exception is the Femring, which releases enough estrogen to cause significant systemic effects.

TABLE 48.2

Intravaginal Estrogens for Menopausal Hormone Therapy*

| Generic Name | Trade Name | Usual Maintenance Dosage |

| VAGINAL CREAMS | ||

| Conjugated estrogens | Premarin | Apply 0.5–2 g/day (625 mcg conjugated estrogens/g).† |

| Estradiol | Estrace | Apply 1–2 g 1–3 times/wk (100 mcg estradiol/g) |

| VAGINAL RINGS | ||

| Estradiol | Estring | This 2-mg ring releases 7.5 mcg/day for 90 days. |

| Estradiol acetate | Femring |

The 12.4-mg ring releases 50 mcg/day for 90 days.* The 24.8-mg ring releases 100 mcg/day for 90 days.* |

| VAGINAL TABLETS | ||

| Estradiol hemihydrate | Vagifem | Insert 1 tablet (10 mcg) every day for 2 wk, then 1 tablet twice a week thereafter. |

Prevention of Osteoporosis

Hormone therapy reduces postmenopausal bone loss and thereby decreases the risk for osteoporosis and related fractures. Unfortunately, when HT is stopped, bone mass rapidly decreases by about 12%. Hence, to maintain bone health, HT must continue lifelong. As a result, the risk for harm is increased. Accordingly, alternative treatments are preferred. In fact, labeling of HT products now must carry the following advice: When this product is prescribed solely to prevent postmenopausal osteoporosis, approved nonestrogen treatments should be carefully considered. Furthermore, HT should be considered only for women with significant risk for osteoporosis, and only when that risk outweighs the risks of HT. As discussed in Chapter 59, effective alternatives to HT include raloxifene [Evista], bisphosphonates (e.g., alendronate [Fosamax]), calcitonin [Miacalcin], and teriparatide [Forteo]. Of course, all women (not to mention men) should practice primary prevention of bone loss by ensuring adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, performing regular weight-bearing exercise, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol use.

Inappropriate Uses: Attempted Prevention of Heart Disease and Dementia

Heart Disease

HT should not be prescribed for the express purpose of preventing CHD. For most women, HT confers no protection and may increase the risk for CHD and MI in some women.

To reduce risk for cardiovascular events, postmenopausal women should be counseled about alternative ways to promote cardiovascular health. Among these are avoiding smoking, performing regular aerobic exercise, decreasing intake of saturated fats, and taking prescribed drugs to treat hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol.

Alzheimer Disease

HT should not be used to prevent Alzheimer disease. There is no evidence that either EPT or ET can protect against dementia, whereas there is evidence that EPT may cause dementia and that ET can increase the combined risk for dementia and mild cognitive impairment.

Discontinuing Hormone Therapy

Unfortunately, discontinuation may cause vasomotor symptoms to return; typically this occurs within 4 days of the last HT dose. Women who had severe symptoms before initiating HT are at highest risk for developing intolerable symptoms when they stop.

No firm guidelines exist for stopping HT. There are two basic methods: immediate cessation and tapering slowly. However, there are no controlled studies to indicate which option might result in fewer symptoms. For women who choose to taper slowly, again there are two basic options, referred to as “dose tapering” and “day tapering.” With dose tapering, dosing is done every day, but the size of the daily dose is gradually reduced. If intense symptoms return after a dosage reduction, further reductions should be delayed until symptoms improve. With day tapering, the daily dose remains unchanged, but the number of days between doses is gradually increased—starting with dosing every other day, then every third day, and so on. Regardless of which method is used—dose tapering or day tapering—only the dosage of estrogen should be lowered. For women on EPT, the progestin dosage should remain unchanged because lowering the progestin dosage might permit estrogen to stimulate endometrial growth, thereby posing a risk for endometrial hyperplasia.

Drug Products for Hormone Therapy

Preparations

Preparations for HT are listed in Tables 48.2, 48.3, and 48.4. Dosing may be oral, transdermal, or intravaginal. The oral estrogens employed most often are conjugated equine estrogens [Premarin] (prepared by extraction from pregnant mares’ urine), estradiol [Estrace], and estropipate. For transdermal therapy, estradiol is the only estrogen employed, formulated in patches, gels, a spray, and an emulsion. Oral estrogen/progestin combinations include conjugated equine estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate [Prempro, Premphase], estradiol/norethindrone acetate [Activella], and ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone [Femhrt]. Combination estrogen/progestin patches are estradiol/norethindrone [CombiPatch] and estradiol/levonorgestrel [ClimaraPro]. Intravaginal products—formulated as tablets, creams, and rings—are used primarily to manage symptoms of urogenital atrophy.

TABLE 48.3

Oral Drugs for Menopausal Hormone Therapy

| Generic Name | Trade Name | Usual Dosage |

| ESTROGENS | ||

| Conjugated estrogens, equine | Premarin | 0.3–1.25 mg/day |

| Esterified estrogens | Menest, Estragen  |

0.3–2.5 mg/day |

| Estradiol, micronized | Estrace | 0.5–2 mg/day |

| Estropipate | Generic only | 0.75–6 mg/day |

| PROGESTINS* | ||

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Provera | 2.5–10 mg |

| Progesterone (micronized) | Prometrium | 200 mg |

| ESTROGEN/PROGESTIN COMBINATIONS* | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | Prempro | 0.3/1.5, 0.45/1.5, 0.625/2.5, or 0.625/5 mg daily |

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | Premphase |

Days 1–14: 0.625 mg estrogen (alone) daily Days 15–28: 0.625/5 mg estrogen/progesterone daily |

| Estradiol/drospirenone | Angeliq | 0.5/0.25 or 1/0.5 mg daily |

| Estradiol/norethindrone acetate | Activella | 0.5/0.1 or 1/0.5 mg daily |

| Estradiol/norgestimate | Prefest | 1 mg estradiol every day; 0.09 mg norgestimate in a repeating cycle of 3 days on and 3 days off |

| Ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone | Femhrt | 2.5 mcg/0.5 mg or 5 mcg/1 mg daily |

| OTHER ESTROGEN COMBINATIONS | ||

| Esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone | Covaryx | 1.25 mg/2.5 mg daily |

| Esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone | Covaryx HS | 0.625/1.25 mg daily |

| Conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene† | Duavee | 0.45 mg/20 mg twice daily |

TABLE 48.4

Transdermal Drugs for Menopausal Hormone Therapy

| Generic Name | Trade Name | Strength (mcg absorbed/day) | Application |

| ESTROGENS | |||

| Transdermal Patches | |||

| Estradiol | Menostar | 14 | Once weekly |

| Climara | 25, 37.5, 50, 60, 75, 100 | Once weekly | |

| Alora | 25, 50, 75, 100 | Twice weekly | |

Oesclim  |

25, 37.5, 50, 75, 100 | Twice weekly | |

| Vivelle-Dot | 25, 37.5, 50, 75, 100 | Twice weekly | |

| Estraderm | 50, 100 | Twice weekly | |

| Topical Emulsion | |||

| Estradiol hemihydrate | Estrasorb | 50 | Once daily |

| Transdermal Spray | |||

| Estradiol | Evamist | 1.53–4.6 mg is applied* | Once daily |

| Topical Gel | |||

| Estradiol | EstroGel | 0.75 mg is applied* | Once daily |

| Elestrin | 0.52 or 1.04 mg is applied* | Once daily | |

| Divigel | 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg is applied* | Once daily | |

| ESTROGEN/PROGESTIN COMBINATIONS | |||

| Transdermal Patches | |||

| Estradiol/norethindrone | CombiPatch | 50/140, 50/250 | Twice weekly |

| Estradiol/levonorgestrel | ClimaraPro | 45/15 | Once weekly |

Dosing Schedules

Every woman undergoing systemic HT receives an estrogen, and every woman with a uterus also receives a progestin to counteract the stimulant effects of estrogen on the endometrium. Several dosing schedules may be employed. Estrogen and progestin are commonly administered continuously. An alternative is to give estrogen continuously but give the progestin cyclically (e.g., on calendar days 15 through 28). However, cyclic progestin has the disadvantage of promoting monthly bleeding, which may explain why most women prefer continuous dosing.

Vaginal estrogens can be given continuously for 1 to 2 weeks, followed by dosing 1 to 3 times per week, titrating the dosing schedule based on symptoms. Estring remains in the vagina for 3 months, after which it is removed and replaced with a new ring.

Prescribing and Monitoring Considerations

Estrogens

Preadministration Assessment

Therapeutic Goal

Estrogens are used primarily for contraception (see Chapter 49) and for menopausal HT but only to prevent osteoporosis, suppress vasomotor symptoms, and manage symptoms related to vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Indications unrelated to HT are female hypogonadism, prostate cancer, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding.

Baseline Data

Assessment should include a breast examination, pelvic examination, lipid profile, mammography, and blood pressure measurement. If the indication for HT is vasomotor symptoms, menopause should be verified by a serum FSH level.

Identifying High-Risk Patients

Estrogens are contraindicated for patients with estrogen-dependent cancers, undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, active thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disorders, or a history of estrogen-associated thrombophlebitis, thrombosis, or thromboembolic disorders. A baseline mammogram can be used to detect breast cancer before prescribing.

Dosing Schedules for Hormone Therapy

Women with an intact uterus should receive estrogen plus progestin, whereas women who have had a hysterectomy should use estrogen alone. In both cases, dosing with oral estrogen is done daily. With estrogen plus progestin, the progestin component may be given daily or cyclically 10 days per month.

Ongoing Monitoring and Interventions

Monitoring Summary

Because these drugs affect breast and uterine function, the patient should receive a yearly follow-up breast and pelvic examination.

Minimizing Adverse Effects

Nausea.

Nausea is common early in treatment. Fortunately, this adverse effect diminishes with time.

Endometrial Hyperplasia and Cancer.

Menopausal HT with estrogen alone increases the risk for endometrial carcinoma. Adding a progestin lowers this risk to the pretreatment level.

Breast Cancer.

Estrogen, combined with a progestin, produces a small increase in the risk for breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Cardiovascular Events.

Estrogen plus a progestin increases the risk for CHD, MI, DVT, pulmonary embolism, and stroke. For women older than 60 years, therapy with estrogen alone carries the same risks. For women aged 50 to 59 years, therapy with estrogen alone increases the risk for DVT, pulmonary embolism, and stroke but may protect against CHD and MI.

Effects Resembling Those Caused by Oral Contraceptives.

Use of estrogens for noncontraceptive purposes can produce adverse effects similar to those caused by oral contraceptives (e.g., abnormal vaginal bleeding, hypertension, benign hepatic adenoma, reduced glucose tolerance). Nursing implications regarding these effects are summarized in Chapter 49.

Minimizing Adverse Interactions

Review current medications at each visit. Use of a drug interaction application is recommended to identify any potential interactions.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

Estrogens

| Life Stage | Considerations or Concerns |

| Children | Estrogens are not indicated for prepubertal children. |

| Pregnant women | Estrogens are contraindicated during pregnancy. |

| Breastfeeding women | Estrogens may they affect infant development and may decrease both the quantity and quality of milk produced. |

| Older adults | Beers Criteria includes estrogens among those identified as potentially inappropriate for use in geriatric patients. |

Progestins

Preadministration Assessment

Therapeutic Goal

Progestins are used for contraception (see Chapter 49) and to counteract endometrial hyperplasia that could be caused by unopposed estrogen during HT. Other uses include dysfunctional uterine bleeding, amenorrhea, endometriosis, and support of pregnancy in women with corpus luteum deficiency. Progestins are also used in IVF cycles and to prevent prematurity in women at high risk for preterm birth.

Baseline Data

The physical examination should include breast and pelvic examinations. A pregnancy test is also warranted in most cases.

Identifying High-Risk Patients

Progestins are contraindicated in the presence of undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding. Relative contraindications include active thrombophlebitis or a history of thromboembolic disorders, active liver disease, and carcinoma of the breast.

Ongoing Monitoring and Interventions

Gynecologic Effects

Progestins can cause breakthrough bleeding, spotting, and amenorrhea. Instruct patients to report any abnormal vaginal bleeding.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

Progestins

| Life Stage | Considerations or Concerns |

| Children | Progestins are not indicated for prepubertal children. |

| Pregnant women | High-dose therapy during the first 4 months of pregnancy has been associated with an increased incidence of birth defects (limb reductions, heart defects, masculinization of the female fetus). |

| Breastfeeding women | Progestins may contribute to neonatal jaundice. |

| Older adults | Progestins are only indicated if the patient is taking estrogen and has a uterus. |

Black Box Warning: Estrogen Therapy

Black Box Warning: Estrogen Therapy Black Box Warning: Estrogen and Progestin Therapy

Black Box Warning: Estrogen and Progestin Therapy