Essential thrombocythaemia and myelofibrosis

Essential thrombocythaemia

Diagnosis

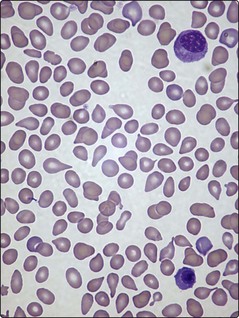

Platelet counts can be as high as 2000 × 109/L and usually exceed 450 × 109/L (the normal range is 150–400 × 109/L) (Fig 33.1). In practice, there is no single test to specifically identify ET – diagnosis is often a process of exclusion. As thrombocytosis may accompany a wide range of disorders including infections, inflammatory conditions, malignancy and iron deficiency, a thorough history and examination is mandatory. The lack of a measurable ‘acute phase response’ (i.e. normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, plasma viscosity and fibrinogen) increases the likelihood of ET as opposed to a ‘reactive’ thrombocytosis. Even where there is an acquired JAK2 gene mutation, other myeloproliferative disorders must be excluded. Bone marrow examination is worthwhile to exclude chronic myeloid leukaemia (absence of Philadelphia chromosome), myelofibrosis or myelodysplasia, and to check iron stores. Patients with polycythaemia vera may have thrombocytosis, while patients with ET can have an increased red cell mass. In practice such patients are better diagnosed as having myeloproliferative neoplasms rather than forced into either category. Only about 5% of all raised platelet counts are due to ET, but persistence of the count above 1000, particularly with coexistence of thrombosis or haemorrhage, makes it the likely diagnosis. Abnormal platelet function tests suggest ET rather than a reactive thrombocytosis.

Myelofibrosis

Clinical features

The disease is often insidious in onset with fatigue and weight loss. Splenomegaly is present in all cases and massive in 10% (Fig 33.4). Splenic pain is common and a bulky spleen may lead to portal hypertension, bleeding varices and ascites. Hepatomegaly is seen in two-thirds of cases.

Diagnosis

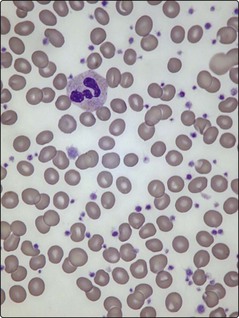

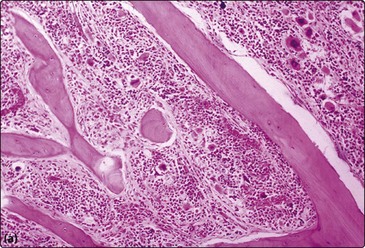

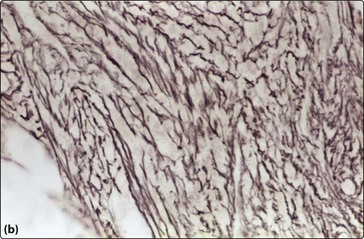

Anaemia is almost universal and the blood film shows tear-drop poikilocytes and a ‘leucoerythroblastic’ picture (Fig 33.2). In the early stages, thrombocytosis and neutrophilia may occur but in more advanced disease low counts are the rule. Bone marrow aspiration characteristically results in a ‘dry tap’ (i.e. only peripheral blood aspirated), and a marrow trephine showing dense reticulin fibres on silver staining, fibrosis and osteosclerosis is needed for diagnosis (Fig 33.3). There is usually megakaryocytic hyperplasia. The JAK2 gene mutation is present in approximately 50% of cases. X-rays often show bone sclerosis. The major differential diagnosis is from other myeloproliferative disorders and myelodysplastic syndromes which may be associated with a degree of marrow fibrosis. Systemic causes of marrow fibrosis such as marrow infiltration by carcinoma or lymphoma and disseminated tuberculosis should also be considered.

Fig 33.2 Blood film in myelofibrosis showing a myelocyte and nucleated red cell (i.e. leucoerythroblastic film) and tear-drop poikilocytes.