CHAPTER 9 Esophageal Replacement

Gastric Tube Pull-up

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

♦ Esophageal atresia remains the most common reason for esophageal replacement in children. The stomach will usually have a normal configuration and, in cases of pure esophageal atresia, will have a gastrostomy tube in place at the time of esophageal replacement. The stomach in pure atresia is diminutive at birth and requires several months of feedings before attaining a normal size.

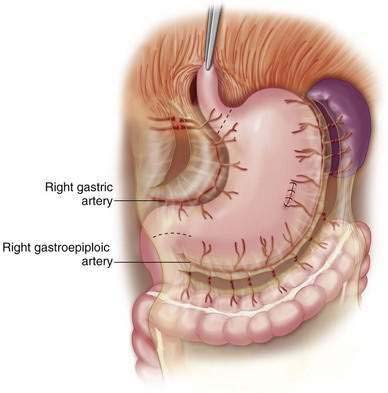

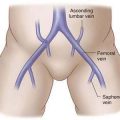

♦ A key element of the anatomy is the blood supply to the stomach. The transposed stomach will rely on the right gastric and the right gastroepiploic arteries, which must be preserved (Fig. 9-1).

♦ The left gastric and the short gastric arteries are ligated to mobilize the stomach. It is prudent to temporarily occlude flow to the left gastric artery using a bulldog clamp before ligation to ensure that the stomach will have adequate perfusion from the remaining vessels. If the perfusion appears inadequate, an alternate esophageal substitution is required.

♦ Another important anatomic point is that the most cephalad portion of the stomach will be the fundus, not the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ).

♦ In cases of atresia, the esophageal bed will be without scarring or adhesions unless previous attempts at repair have been made. Significant scar formation may be present in children with severe caustic injury to the esophagus and in cases where there is a history of perforation or prior attempts at a replacement procedure.

♦ In some cases, a cervical esophagostomy may be present at the time of surgery. This will usually be on the left side of the lower neck, which is more desirable because the path through the mediastinum is shorter to this side. It is critical to be aware of the vagus and the recurrent laryngeal nerves at the time of surgery. Both recurrent laryngeal nerves can be injured and will result in severe respiratory compromise because of vocal cord paralysis.

Step 2. Preoperative Considerations

♦ We recommend preoperative admission for bowel preparation in case the stomach is not usable for esophageal replacement and the colon is required.

Step 3. Operative Steps

Anesthesia

Positioning

♦ The cervical anastomosis is typically performed on the left side of the neck; thus we position the patient in a modified supine position with a roll beneath the upper back to expose the neck. In addition, the left shoulder and upper arm are prepared in the field with a stockinette on the lower arm to allow manipulation during the case as needed.

Incisions

♦ A cervical incision is required to identify the proximal esophagus. In some cases, there will be an existing cervical esophagostomy.

♦ The incision is made on the anterolateral surface of the left neck, approximately 2 to 3 cm above the clavicle, and is placed between the heads of the sternocleidomastoid.

♦ Dissection is carried out between these heads, and the medial aspect usually needs to be transected for adequate exposure.

♦ The trachea is identified, and the tracheoesophageal groove is seen just below, where care is taken to identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve. At this point, it is helpful to have a bougie or a Bakes dilator in the esophageal pouch (especially for an atresia) to identify it.

♦ When the esophagus has been identified, traction stitches can be placed in it to retract it laterally; care needs to be exercised to prevent injury to the opposite recurrent laryngeal nerve.

♦ Use of electrocautery near the recurrent laryngeal nerves is minimized. Dissection is continued behind the trachea and anterior to the spine to circumscribe the esophagus.

♦ The blood supply to the stomach is carefully assessed, and bulldog clamps may be placed on the left gastric artery while taking down the short gastric vessels at least 1 to 2 cm away from the gastroepiploic artery.

♦ The left gastric artery will also have to be ligated to allow the stomach to reach the cervical region.

♦ In most cases, the stomach will retain an excellent blood supply, which is verified by the temporary clamping.

♦ The distal esophageal end is then dissected free from the hiatus, and blunt dissection is carried out into the mediastinum. Dissection may be tedious in cases where scarring and adhesions from prior procedures or antecedent perforations are present. In cases of atresia, the stump is mobilized and transected with a stapler and then oversewn.

♦ The highest point of the stomach is usually the fundus and not the GEJ. Adequacy of the length is verified by placing the mobilized stomach over the chest and neck.

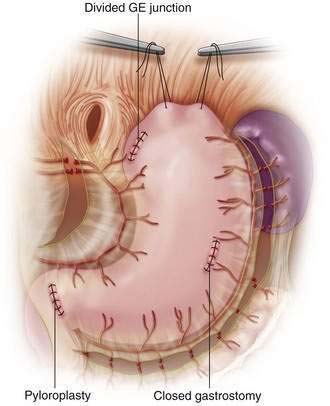

♦ At this point, a pyloromyotomy or pyloroplasty is performed to assist in gastric emptying. A pyloromyotomy will be adequate for most patients and is greatly preferred to maintain gastric length (Fig. 9-2). A Kocher maneuver is performed to gain additional length.

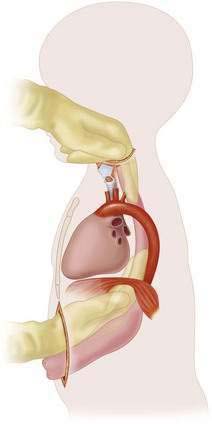

♦ Mediastinal dissection is carried out bluntly from the hiatal area below and from the neck above (Fig. 9-3). In smaller children, this may be accomplished by using fingers alone, but in older patients a sponge stick or blunt Kelley clamp will be needed.

♦ In some cases in which there is excessive scar tissue or a native esophagus that cannot be removed safely, a left thoracotomy may need to be performed as well.

♦ Once the dissection is completed, the area is stretched with two or three fingers to make room for the stomach. The hiatus must often be opened to allow the stomach to pass successfully. It is critical that the stomach passes to the left of the aortic arch.

♦ A large chest tube (28 to 36 French) is then passed from the neck down to the abdomen through the mediastinal space that was created. This is attached to the fundus of the stomach with a 0 silk stitch through the tube and stomach. To prevent twisting of the stomach during transposition, two sutures of different colors may be placed on the fundus before carefully pulling it up into the cervical region. There is usually no tension on the transposed stomach when placed in the neck area.

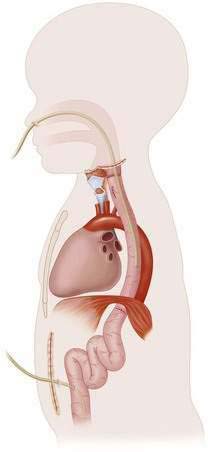

♦ To decrease tension on the anastomosis, the stomach is sutured to the sternocleidomastoid and the strap muscles in infants and the prevertebral fascia in older children. The hiatus is sutured to the stomach to prevent herniation.

♦ Anastomosis between the stomach and the cervical esophagus is performed in a single layer with absorbable suture. A nasogastric (NG) tube of sufficient size (14 to 16 French) is placed with the tip located at the level of the hiatus, above the pyloroplasty (Fig. 9-4). We may perform a jejunostomy for enteral nutrition, particularly in cases of esophageal atresia, where oral aversion may exist.

Step 4: Postoperative Care

♦ Patients are intubated at least overnight and possibly longer because edema can develop in the cervical tracheal area as a result of the dissection.

♦ Acute gastric dilation can occur if the NG does not function well, and this may cause respiratory difficulties. Antibiotics are administered for at least 24 hours.

Step 5: Pearls and Pitfalls

♦ Leaks are seen from the cervical anastomosis in about 25% to 50% of cases, but almost all will heal spontaneously.

♦ In cases where a cervical esophagostomy is performed, consideration should be given for sham feedings to ameliorate oral aversion issues.

Hirschl RB, Yardeni D, Oldham K, et al. Gastric transposition for esophageal replacement in children. Ann Surg. 2002;236:531-541.

Spitz L. Gastric replacement of the esophagus. In: Spitz L, Coran AG, editors. Pediatric surgery. 6th ed. London: Edward Arnold; 2007:145-152.

Spitz L, Kiely E, Pierro A. Gastric transposition in children—a 21-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:276-281.