CHAPTER 45 Esophageal Disorders Caused by Medications, Trauma, and Infection

MEDICATION-INDUCED ESOPHAGEAL INJURY

Medication-induced esophageal injury may occur at any age and with a variety of commonly used medications. Nevertheless, medication-induced esophageal injury is most likely underdiagnosed in clinical practice for several reasons. First, initial consideration of common and more serious problems such as an acute coronary syndrome or pulmonary embolism may occur due to the severe chest pain, often pleuritic in nature, that may be associated with pill-induced esophagitis. Second, patients may be assumed to be having a severe episode of acid reflux, a far more common condition than a medication-induced esophageal ulceration. Third, several of the medications that may cause medication-induced esophagitis are over-the-counter medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) or may have been taken safely for years (e.g., tetracycline) without injury and therefore not considered by patients to be a possible contributor to their symptoms. Fourth, because it is not routinely reported or recognized, medication-induced esophageal injury is often considered an uncommon entity.1,2 As a result, medication-induced esophageal injury often may not be considered. This can be problematic because recognition of this entity might result in failure to discontinue the offending agent or to give the patient proper instruction in avoiding future injury. It may also lead to extensive and erroneous evaluation and treatment of other conditions. This chapter provides a detailed overview of medication-induced esophageal injury, with particular attention to suspecting this entity both by its symptoms and by the medications that are potentially culpable.

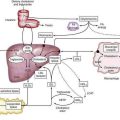

MECHANISMS

Medications may cause esophageal injury through several mechanisms. These can initially be divided into those that cause direct injury to esophageal mucosa because of their caustic nature or by facilitation of injury through another mechanism such as induction of acid reflux (e.g., calcium channel antagonists). When medications directly damage the esophageal mucosa, it may be through one of four known mechanisms: (1) production of a caustic acidic solution (e.g., ascorbic acid and ferrous sulfate); (2) production of a caustic alkaline solution (e.g., alendronate); (3) creation of a hyperosmolar solution in contact with esophageal mucosa (e.g., potassium chloride); and (4) direct drug toxicity to the esophageal mucosa (e.g., tetracycline). For many medications, the mechanism of esophageal injury does not fall into any of these known categories. Other factors may influence the toxicity of the pill, particularly contact time, pills coated with gelatinous material,3 sustained release formulations, and a wax matrix form of the drug.4 Cellulose fiber and guar gum pills may swell and lodge in the esophagus, causing complete obstruction because of their water-absorbing capacity.

It is commonly assumed in medication-induced esophagitis that injury is predisposed by an anatomic or motility disorder of the esophagus or that the medication was taken incorrectly, in either case allowing for prolonged exposure of the medication to esophageal mucosa. For example, studies have shown that patients with left atrial enlargement,5 esophageal strictures,6 esophageal dysmotility,7 and esophageal diverticula8 (either Zenker’s or epiphrenic diverticula) have greater risk of pill injury. Similarly, in the patient with normal esophageal function, the site of drug-induced injury most commonly occurs where there are areas of normal hypomotility or extrinsic compression such as in the trough zone of the esophagus (where the smooth and skeletal muscle overlap) or at the level of the aortic or left bronchial impression on the esophagus.9,10 These locations of relative stasis allow for a pill, when taken incorrectly, to cause injury. However, any part of the esophagus may be involved. Methods of taking a medication incorrectly that predispose to injury include ingesting a pill without enough water or assuming a recumbent position or sleeping immediately after pill ingestion, or both. The latter two factors are particularly problematic, by eliminating the help of gravity in esophageal transit and by reducing saliva production and frequent swallowing, which occur normally while awake. Importantly, however, many, if not most, patients who suffer pill-induced esophageal injury presumably have normal esophageal function and do not necessarily ingest their medication in a faulty manner. That pill-induced esophageal injury can occur under “normal” conditions is supported by data demonstrating prolonged radiographic retention of capsules in the esophagus by normal subjects even when taken with water in the upright position.3,11

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

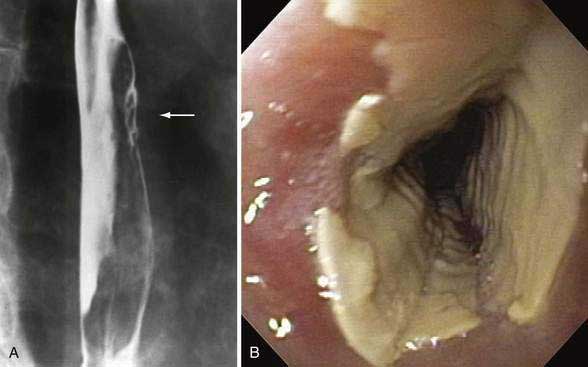

Patients typically note an acute onset of chest pain, which may radiate over the central chest and to the back. The pain is commonly accentuated with inspiration and may be accompanied by severe odynophagia, even to small sips of liquids. Some patients may complain of a severe acute onset or heartburn-type symptoms. This set of symptoms associated with a potentially injurious medication taken incorrectly (particularly just before bedtime without enough water) strongly suggests the diagnosis. If objective confirmation of the diagnosis is necessary, endoscopy or radiography can be used. Endoscopy is felt to be more sensitive, although trials comparing the two have not been performed. Findings range from discrete ulcers to diffuse severe esophagitis with pseudomembranes, as may be seen with bisphosphonates12 or with sodium polystyrene sulfonate suspension (Kayexalate), in which the appearance may mimic candidal esophagitis.13 Occasionally, severe inflammatory reactions causing stenoses and tumor-like appearances may occur.14,15 Similar findings may be seen radiographically, particularly when double-contrast radiography is used.16,17 The range of findings described on esophagography may also include solitary or multiple ulcers; small or large ulcerations; ulcers with punctate, ovoid, linear, serpiginous, or stellate collections of barium; confluent ulcers; or areas of normal-appearing mucosa separating ulcers (Fig. 45-1).9 The occurrence of multiple esophageal septa has also been described.18 Rarely, severe complications of medication-induced injury may occur. These may include esophagorespiratory fistula, esophageal perforation, hemorrhage secondary to ulceration, and chronic stricture formation.

PREVENTION, TREATMENT, AND CLINICAL COURSE

No specific treatments have been shown to be beneficial in altering the course of medication-induced injury. Treatment is aimed at symptom control, prevention of superimposed injury from acid reflux, maintenance of adequate hydration, and removal of the offending medication. Symptom control may be achieved topically by local anesthetics such as viscous lidocaine solution. Occasionally, narcotics are necessary. Prevention of superimposed reflux is best achieved with a twice-daily proton pump inhibitor, although no data clearly suggest that prevention of acid reflux hastens symptomatic or pathologic improvement of pill-induced injury. For patients who have severe odynophagia prohibiting adequate oral intake, intravenous hydration may be necessary for a few days. Removal of the cause of injury is self-evident, although this is not always easily achieved. This is particularly true in clinical situations in which there may not be an adequate substitute such as in aspirin prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease, bisphosphonates for severe osteoporosis, or high-dose NSAIDs for pain from chronic inflammatory arthritides. No data address the question of whether rechallenge with a pill that induced prior esophagitis poses higher risk of recurrent injury if the pill is taken with better caution, with the possible exception of bisphosphonates. It is also unclear if patients with a theoretical underlying risk (e.g., esophageal dysmotility) have even greater risk of esophagitis with rechallenge. In the absence of stricture formation or catastrophic presentation, most patients have clinical resolution of symptoms within two to three weeks, and radiographic resolution has been described in 7 to 10 days.16

Because no treatment has been proven effective, it is hoped that proper administration of potentially injurious medications will help avoid occurrence of esophageal injury. On the basis of the sometimes normally slow transit of medications through the esophagus, particularly for gelatin capsules and larger tablets,3 the following recommendations are made: (1) medications should be swallowed with at least 8 ounces of a clear liquid; (2) patients should remain upright for at least 30 minutes following ingestion of the medication; (3) in patients with potential underlying increased risk for pill-induced injury (e.g., inability to follow the previous instructions, poor esophageal motility, anatomic compromise of the esophageal lumen), one should search for alternative safer medications or carefully weigh the risks and benefits of this medication against the disease for which this medication is necessary.

SPECIFIC MEDICATIONS

Antibiotics (Table 45-1)

Tetracycline, doxycycline, and their derivatives are by far the most common causes of pill-induced esophagitis, with almost as many cases reported as all other cases combined.10 Its commonality of injury may be more a reflection of how frequently the drug is used than a strong propensity of tetracycline to produce such injury. This relatively low incidence of esophageal ulceration from tetracycline for all users is suggested by a lack of any cases of esophageal injury seen in a recent survey of 491 Gulf War veterans treated with doxycycline.2 The mechanism of injury is felt to be corrosive damage because tetracycline dissolved in water produces a solution with a very low pH.11 Symptoms typically last several days to several weeks. Ulcerations may vary in appearance but are typically small and superficial, located in the mid-esophagus just above the aortic arch or left mainstem bronchus9 with a burn-like appearance (see Fig. 45-1). Stricture formation is uncommon.

Table 45-1 Medications Commonly Associated with Esophagitis or Esophageal Injury

Injury from other antibiotics is uncommon and mostly documented in case reports. These include clindamycin,19,20 rifampin,21 and penicillin,22 but the incidence is still exceedingly low given their common use. If a history is compatible with pill-induced esophageal injury, any antibiotic currently being used should be considered a possible culprit, although rare.

Antiviral agents, particularly those used for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus, also have been reported to cause medication-induced esophageal injury. These include zalcitabine,23 zidovudine,24 and nelfinavir.25

Bisphosphonates

To date, injury has been reported mostly with alendronate12,26–32 but also with etidronate33 and pamidronate.34 Although the overall incidence of injury is probably small (fewer than 100 cases reported)10 when considering the millions of patients using the medication, injury can be serious and even fatal. Unfortunately reflux-type symptoms are common and can be difficult to distinguish from medication-induced mucosal injury. Risedronate has low potential for causing esophageal injury, if at all.35 Part of this might be explained by the rapid esophageal transit and subsequently minimal contact time of the drug with esophageal mucosa.36 In one study prospectively following 255 patients treated with risedronate and undergoing endoscopy 8 and 15 days later, no patients developed esophageal ulceration. This study also underscored the overall safety of bisphosphonates in general in that only 3 of 260 patients receiving alendronate developed esophageal ulceration.37

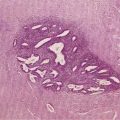

Diagnosis is best made endoscopically, with marked exudates and inflammation seen. Biopsies show an intense inflammatory exudate and granulation tissue that may contain polarizable crystals and multinucleated giant cells.38 Stricture formation occurs in up to one third of patients,10 and life-threatening hemorrhage30 and esophageal perforation28 have been reported. Patients who sustain injury are described commonly to take the bisphosphonate not in accordance with directions (i.e., in the upright position with at least 8 ounces of beverage, remaining upright for at least 30 minutes). Still, as with other pill-induced esophagitides, patients taking the medication correctly may sustain esophageal injury. One question frequently answered anecdotally, but not clearly addressed scientifically, is whether patients with a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should avoid bisphosphonates. Furthermore, if GERD is a risk factor, it is unclear what degree of reflux constitutes risk. The decision should weigh the severity of osteoporosis and risk of fracture against the risk of esophagitis. Patients with GERD that predisposes to stasis such as those with stricture or severe ineffective esophageal motility should be particularly cautious.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs are another common cause of pill-induced esophageal injury. Similar to the other common causes or medication-induced esophageal injury, they occur in a small fraction of all NSAID users. Aspirin, naproxen, indomethacin, and ibuprofen account for the majority of cases,10 but most other NSAIDs have been reported to cause esophageal injury in case reports. Not surprisingly, hemorrhage, which may be severe,39 is a common complication of these esophageal ulcers, especially when compared with other medication causes of esophagitis. Bronchoesophageal fistula has also been reported.40 Notably, it is over-the-counter use of NSAIDs that is most commonly associated with injury,41 in keeping with their more commonly used venue.

In a study of 1122 patients hospitalized for gastrointestinal bleeding, any dose of aspirin including a low dose was associated with increased risk of developing esophagitis.42 Other studies have also identified NSAIDs in general as a risk factor for erosive esophagitis.43 Whether the esophagitis in these studies is all directly due to these medications or whether they act synergistically with reflux-induced injury is unclear, although one study has suggested that aspirin makes the esophageal mucosa more sensitive to acid and pepsin.44

Other Medications Commonly Associated with Pill-Induced Injury

Potassium chloride (KCl) pills have been associated with esophageal injury. Injury can be severe, as documented by reports of esophageal stricture formation45,46 or of perforation into the left atrium,47 bronchial artery,48 or mediastinum.49 Patients who sustain esophageal injury from KCl commonly report associated conditions such as cardiac, including left atrial, enlargement, or prior cardiac surgery.50–52 Whether these processes truly predispose to pill stasis and injury because of extrinsic esophageal compression by the heart is unclear, because patients using KCl have a high prevalence of cardiac disease.

Quinidine is another cardiac medication with the potential for severe esophagitis.15 Endoscopically, quinidine may be associated with anything from mild ulceration to a marked inflammatory response with edema suggesting carcinoma.14,15 Ferrous sulfate,53 theophylline,54,55 oral contraceptives,56 ascorbic acid,22 and multivitamins57 have caused esophageal ulceration. Numerous other medications have been reported to cause esophageal ulceration in single case reports. Examples include sildenafil,58 phenytoin,11 warfarin,59 glyburide,60 lansoprazole,61 valproic acid,62 chlorazepate,63 captopril,64 foscarnet,65 and throat lozenges.66,67

Chemotherapy-Induced Esophagitis

Dactinomycin, bleomycin, cytarabine, daunorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine, and chemotherapy regimens used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may cause severe odynophagia as a result of oropharyngeal mucositis, a process that can also involve the esophageal mucosa.68 Esophageal damage is unusual in the absence of oral changes. Although mucositis is self-limited in most cases, some patients have oral and esophageal damage that persists for weeks to months. Chemotherapy that is given months after thoracic irradiation to the esophagus, particularly doxorubicin, may cause a “recall” esophagitis. Vinca alkaloid drugs are neurotoxic, and dysphagia may complicate vincristine therapy.69

Esophageal Injury from Variceal Sclerotherapy

Complications from variceal sclerotherapy can be divided into two main categories: gross structural injury and esophageal motility change. There is a wide range of gross injury from variceal injection. Injection of sclerosant into and around varices causes necrosis of esophageal tissues and mucosal ulceration; the risk is related to the number of injections and the amount of sclerosant. Small ulcers appear within the first few days after sclerotherapy in virtually all patients; larger ulcers develop in roughly one half of patients. Other complications include intramural esophageal hematoma,70 strictures,71 and perforation.72 Strictures occur in approximately 15% of patients undergoing sclerotherapy71,73,74 and are usually amenable to Savary or balloon dilation. Unusual manifestations of sclerotherapy with deep needle penetration include pericarditis, esophageal-pleural fistula, and tracheal obstruction due to compression by an intramural hematoma.75,76 One case of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus was attributed to a course of variceal sclerotherapy five years earlier.77

Several studies have demonstrated abnormal esophageal motility after completed courses of sclerotherapy. These abnormalities may be related to wall injury or vagal dysfunction.78 Specific motility abnormalities include delay in esophageal transit and decreased amplitude and coordination of esophageal contractions.74,79 There is debate over whether these changes are reversible, with different studies demonstrating worsening74 or resolution80 of motility abnormalities over four weeks’ time. Whether these studies reflect the effects of irreversible fibrosis or reversible inflammatory neuropathy, respectively, is unclear. One potential consequence of motility dysfunction is the occurrence of pathologic gastroesophageal reflux, as documented by abnormal esophageal pH monitoring81 and by abnormal scintigraphy and barium studies after sclerotherapy.74 Other studies have also shown abnormal reflux following sclerotherapy that correlated with esophageal dysmotility, and this did not occur in patients undergoing band ligation.79 Furthermore, the amount of sclerosant injected paravariceally appears to correlate with increased acid reflux.81

The only agent that has been shown effective in preventing postsclerotherapy strictures and in healing ulcers is sucralfate, either alone or in combination with antacids and cimetidine.82,83 Acid suppressive therapy alone, with either H2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors, has not been shown to be effective in preventing or healing postsclerotherapy ulcers or strictures.84,85

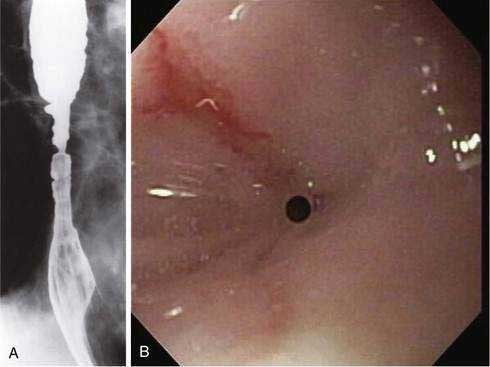

ESOPHAGEAL INJURY FROM NASOGASTRIC AND OTHER NONENDOSCOPIC TUBES

Nasogastric tubes have long been recognized as a potential source of esophageal injury and stricture formation (Fig. 45-2). The putative mechanism is gastroesophageal reflux. In patients undergoing elective laparotomy, recent data have demonstrated an esophageal pH of less than 4 for nearly 9 of the first 24 hours compared with less than one half hour in a control group without tube placement.86 One study demonstrated an increase in acid exposure even in normal volunteers undergoing nasogastric tube placement.87 When strictures occur, they are characteristically long, narrow, and difficult to manage endoscopically. Whether general use of potent acid-suppressing therapies has decreased the incidence of these strictures is unknown.

Respiratory luminal devices have also been reported as potential sources of esophageal trauma. Esophageal laceration with use of a Combitube,88 tracheoesophageal fistula with a cuffed tracheal tube,89 and esophageal perforation from a thoracostomy tube90 or transesophageal echocardiography probes91 have been reported.

More recently, several authors have reported the occurrence of an atrial-esophageal fistula complicating cardiac radiofrequency ablation procedures.92–96 This serious and often fatal complication has been described to occur anywhere from 10 days to five weeks after ablation. The initial presentation includes fever and neurologic abnormalities, the latter as a result of air emboli to the brain from the esophagus through the fistula into the left heart. Laboratory studies may reveal leukocytosis and positive blood cultures. Imaging studies may reveal gas bubbles in the left atrium. Although generally fatal due to sepsis and upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage, a recent report describes one patient who survived with surgical repair of the fistula,95 suggesting that prompt recognition may reduce mortality.

ESOPHAGEAL INJURY FROM PENETRATING OR BLUNT TRAUMA

Noniatrogenic traumatic injury to the esophagus may occur through either penetrating or, less commonly, blunt injuries. Blunt trauma resulting in esophageal perforation is exceedingly rare; most cases have occurred in the cervical esophagus after motor vehicle accidents from the steering wheel97 or seat belt.98 Penetrating injuries to the esophagus are usually caused by gunshot or knife wounds, although cervical esophageal perforation secondary to cervical spine surgery has been well recognized.99 In general, injuries from penetrating wounds are divided into those of the cervical and lower esophagus. Perforation of the cervical esophagus may be diagnosed initially by the finding of extramural air on radiographic studies such as lateral views of the neck or computed tomography. Gastrografin contrast studies confirm the diagnosis, although this test is not always possible in patients with severe traumatic injuries. Although routine endoscopy is relatively contraindicated in these patients, intraoperative endoscopy may be a valuable diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of perforation.100

Cervical esophageal penetrating injuries are usually associated with concurrent tracheal, carotid, or spinal injury. One area of debate in management of these injuries is whether surgical exploration is necessary in all patients. The concern in waiting is the development of sepsis, airway compromise, or tracheoesophageal fistulae,101 estimated to occur in approximately 4% of penetrating esophageal wounds102 and particularly in those patients undergoing tracheostomy for tracheal damage. Another downside of watchful waiting is the contamination of a previously sterile field. This may eliminate the option of primary closure and necessitate a two-step procedure, first with performance of a diverting cervical esophagostomy before definitive repair. As a result, some investigators continue to recommend an aggressive multimodal surgical approach.99 In contrast, a recent study of 17 patients with cervical esophageal injury from knife or gunshot wounds suggested that conservative management with enteral feeding and antibiotics may allow for nonoperative healing.103 A consensus seems to be that in those patients with contained small luminal cervical perforation, without sepsis and without the need for surgical exploration for other injuries, a conservative approach may be tried.104

For penetrating trauma to the more distal esophagus, similar principles apply but with some important differences. First, although diagnosis is often made by finding extraesophageal air on either chest or computed tomography (or finding extravasation on contrast study of the esophagus), endoscopy may be performed, particularly for those unstable patients in whom contrast esophagography is not practical.105 Some investigators feel that endoscopy should be the diagnostic test of choice.106 Second, as opposed to a more contained perforation that occurs in the neck as dictated by its close tissue planes, perforation in the more distal esophagus may extend farther into the mediastinum and pleura. Also, there is a threat of coexistent injury to the aorta.

Third, because of the segmental and often variable esophageal blood supply (particularly in the distal esophagus), simple closure of a perforation is not often adequate due to wound ischemia and consequent leakage.107 As a result, esophageal resection with esophagogastric anastomosis is often necessary in these patients.105 Fourth, because access to the esophagus through the mediastinum is so much more difficult than access through the neck, the consequences of perforation into the mediastinum, pleura, or aorta can be more devastating, and the surgery required for distal esophageal perforation may be much more extensive. As a result, the decision whether to operate is far more difficult. Despite these caveats, surgery is not only recommended in most patients107,108 but must be performed in a timely fashion because there is significantly higher morbidity and mortality when surgery is delayed beyond 1 to 12 hours.109 There may be a role for conservative management, with antibiotics and nasogastric tube placement bypassing the perforation, in only a select group of patients. Finally, although metallic stents have been used successfully for nonoperative management of other causes of esophageal perforation,110 their role in managing traumatic perforation of the esophagus has not been studied and should not be considered at this time.

ESOPHAGEAL TEARS AND HEMATOMAS

MALLORY-WEISS SYNDROME (see also Chapter 19)

The Mallory-Weiss syndrome was originally described by Doctors Kenneth Mallory and Soma Weiss in 1929, who described patients with lacerations of the gastric cardia due to forceful vomiting.111 The laceration is felt to result from shearing forces on the gastroesophageal junction and proximal stomach as it herniates through the diaphragm because of high intra-abdominal pressures due to forceful vomiting.112,113 In accordance with Laplace’s law, this shearing force has its greatest effect when there is a hiatal hernia, thus exposing a relatively large-volume dilated sac to high wall tension. It is not surprising that the majority of patients who sustain a Mallory-Weiss tear have a hiatal hernia.114 Although most tears will occur within 2 cm of the gastroesophageal junction, the likelihood of a more distal tear in the proximal portion of the stomach is increased when a larger hiatal hernia is present. Any bodily action that results in an abrupt increase in intra-abdominal pressure and gastric herniation may cause a Mallory-Weiss tear. Such actions include forceful coughing, straining, retching during endoscopy, transesophageal echocardiography, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.112,115–120 Other factors that predispose to tearing include alcohol and aspirin use.113,121–122

Most patients present with hematemesis, but some present with melena alone. Although a classic history includes vomiting or retching followed by hematemesis, up to a third of patients do not have an antecedent history of vomiting; hematemesis is their presenting symptom.121,122 Typically, one laceration is seen at the time of endoscopy, most commonly along the lesser curve of the cardia, although more than one tear may occur in up to 10% of patients.114 Bleeding is typically self-limited, but may be massive in up to 10% of patients114 and even fatal.123 Endoscopy is also important not for diagnosing a tear but for ruling out other upper gastrointestinal lesions that are found in more than a third of patients during the initial endoscopic evaluation. Such lesions include peptic ulcers, gastritis or gastropathy, erosive esophagitis, esophageal varices, and gastric outlet obstruction.

Treatment for Mallory-Weiss tear has usually been supportive because of the self-limited nature of the bleed, along with attempts to reduce retching and vomiting. More recently, several methods of endoscopic therapy have been used. Injection of epinephrine and polidocanol has been shown to significantly reduce bleeding and transfusion requirement and to shorten the hospital stay.124 Endoscopic band ligation also has been shown to be efficacious125,126 and in one trial was equivalent to injection therapy.127 Endoscopic clip placement has also been suggested as a therapeutic alternative for controlling bleeding from Mallory-Weiss tears.128 For patients with persistent bleeding despite endoscopic therapy, angiographic embolization through the left gastric artery may be used.129 The need for surgical intervention is rare.

BOERHAAVE’S SYNDROME

A more extreme version of an esophageal tear that occurs in response to an acute increase in intra-abdominal pressure and accentuation of the intragastric-to-intrathoracic pressure gradient is Boerhaave’s syndrome. In this syndrome, a transmural tear with perforation occurs. The perforation specifically occurs at the margin of the contact between “clasp” and oblique esophageal fibers.130 Similar to the Mallory-Weiss syndrome, preceding symptoms such as severe vomiting and retching, abdominal straining, blunt trauma, and coughing may precipitate this perforation.114 In addition to acute pressure changes at the gastroesophageal junction, some investigators have postulated that an abnormal esophageal mucosa may predispose to perforation. These conditions include reflux esophagitis,131 Barrett’s esophagitis with ulceration,132 infectious esophagitis,133,134 and eosinophilic esophagitis.135

The clinical presentation is often catastrophic with shock and sepsis due to a large esophageal perforation. Because of the acute presentation of severe chest pain, it is often confused with acute cardiac or pulmonary events, dissecting aortic aneurysm, or pancreatitis,136 often leading to a delay in diagnosis and greater morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis is suggested by subcutaneous emphysema with crepitus and radiographic findings of pneumomediastinum and a left pleural effusion (that may contain salivary amylase, erroneously suggesting pancreatitis) or even a frank empyema. Perforation of the esophagus may be confirmed by esophageal contrast studies using Gastrografin. Management is surgical repair and drainage, although successful nonoperative treatment has been reported with placement of a self-expandable plastic stent.137

SPONTANEOUS ESOPHAGEAL HEMATOMA

Spontaneous esophageal hematoma is a rare entity in which an abrupt bleed occurs between the mucosa and muscularis propria of the esophageal wall, often for a long length of the esophagus. The term spontaneous is somewhat of a misnomer in the sense that several underlying factors have been identified that may predispose to hematoma formation. These include use of aspirin,138,139 underlying coagulopathy or use of anticoagulant,140,141 abrupt increases in the intrabdominal-to-intrathoracic pressure gradient such as may occur with forceful vomiting, coughing or sneezing,142 and foreign body ingestion.143 Not all cases have an obvious predisposing factor, however, and do in essence present spontaneously.144 One third of patients classically present with a triad of retrosternal chest pain, dysphagia, and hematemesis and 50% present with at least two of these symptoms.144 As in Boerhaave’s syndrome, there is often a delay in diagnosis because of the symptomatic overlap with more common cardiopulmonary catastrophes.145 Interestingly there may be a predisposition to this syndrome in middle-aged women, although this association is not uniform.146–148

Diagnosis can be made by several means. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrates a diffusely thickened esophagus and sometimes a “double barrel” appearance with obliteration of the esophageal lumen.149 Magnetic resonance imaging also may be an accurate means of making the diagnosis.150 Endoscopically, obliteration of the esophageal lumen is seen with visualization of a long, deep, friable, blue submucosal mass with or without a visible tear.143 Sometimes it may be difficult to distinguish hematoma from an esophageal malignancy.151 Conservative treatment is the mainstay of treatment, maintaining the patient without oral intake and monitoring hemodynamic status143; it usually takes up to several weeks to fully heal. Progress is monitored on repeated CT or endoscopy, usually at one-week intervals. The need for surgical intervention is rare.

ESOPHAGEAL INFECTIONS IN THE IMMUNOCOMPETENT HOST (Table 45-2)

Esophageal infections are most common in immunocompromised patients such as those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (see Chapter 33) and those receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapies, particularly for hematologic malignancies or following organ transplantation (see Chapter 34). Nevertheless, there are some esophageal infections that occur in immunocompetent hosts. These include infections that (1) are more typically associated with immunodeficiency but are occasionally seen in patients with intact immune systems; (2) occur in patients with underlying esophageal diseases, particularly with those associated with prolonged stasis of luminal content; and (3) involve the esophagus because of a localized area of esophageal immune compromise such as with the use of inhaled topical steroids for respiratory disorders. The types of organisms found in these situations tend to be few in number, with Candida the dominant organism.

Table 45-2 Esophageal Infections in the Immunocompetent Host

CANDIDA ALBICANS

Candidal organisms are the most common esophageal infection in the immunocompetent host. Although several species of Candida have been implicated in esophageal infection, including Candida tropicalis, Candida albicans accounts for the vast majority. In one large series of 933 patients in India with dysphagia or odynophagia, 56 were found to have candidal esophagitis of varying severity.152 How many patients had clear motility disorders or Candida as a commensurate rather than a pathologic organism is not totally clear because Candida colonization of the esophagus in healthy ambulatory adults has a reported prevalence of approximately 20%.153

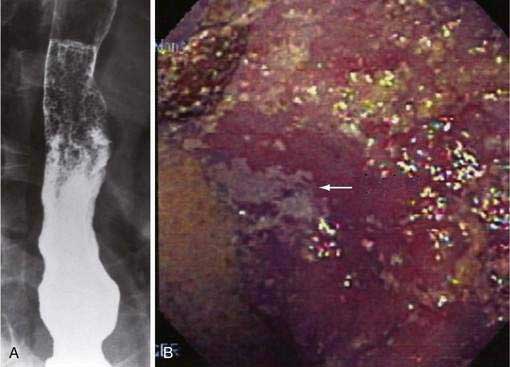

Although candidal esophagitis may occur rarely without a clear underlying mechanism, one should generally assume a predisposing condition, even in the immunocompetent host. The conditions that most predispose to candidal infection in the esophagus are those associated with severe stasis such as achalasia or scleroderma (Fig. 45-3). In achalasia, infection seems related to severity, with those patients who have long-standing disease with marked esophageal dilation most at risk. These infections can be very difficult to treat medically until effective achalasia therapy, and therefore drainage of the esophagus, is provided. Candida is seen less often in scleroderma with esophageal involvement than in achalasia but, similarly, is usually seen in those patients with esophageal dilation and poor peristalsis. One risk factor for candidal infection in scleroderma might be acid suppression, as suggested by one study of patients with systemic sclerosis, in which the prevalence of Candida esophagitis was 44% (21 of 48 patients) for those on no acid suppression, compared with 89% (16 of 18 patients) among those on potent acid suppressive therapy.154 Topical glucocorticoids (contained in inhalers for treatment of asthma) may lead to oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in otherwise healthy adults.155 Likewise, candidal esophagitis has been described and must be considered in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with swallowed fluticasone.156,157 Other medical illnesses that predispose to fungal esophagitis albeit via impaired immune mechanisms include diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, alcoholism, and advanced age.158 Also a rare condition known as esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis of the esophagus may be associated with candidal infection.159 Diagnosis of candidal esophagitis can be made by its endoscopic appearance, with a characteristic white pseudomembranous or plaque-like appearance adherent to esophageal mucosa. Confirmation can be made by brushing the lesion followed by cytology or biopsy, in which inflammation, hyphae, and masses of budding yeast are seen (not usually seen with colonization alone). The entity of the “black esophagus” has also been described with candidal esophagitis.160 Although not as sensitive as endoscopy, candidal esophagitis may be diagnosed by double-contrast barium esophagography.161 The characteristic findings are discrete plaque-like lesions oriented longitudinally, with linear or irregular filling defects with distinct margins produced by trapped barium. Occasionally mass-like lesions and strictures may be seen.

HERPES SIMPLEX

Herpes simplex esophagitis has been described in the immunocompetent host162–164 and can represent either primary infection or, more commonly, a reactivation of latent virus in the distribution of the laryngeal, superior cervical, and vagus nerves. All ages are affected, and oropharyngeal lesions are found in only one in five cases. Severe odynophagia, heartburn, and fever are the dominant symptoms. Nausea, vomiting, and chest pain also may occur. The endoscopic appearance is characterized by diffuse friability; ulceration; and exudates, mostly in the distal esophagus. Classically, the earliest esophageal lesions are rounded 1- to 3-mm vesicles in the mid- to distal esophagus, the centers of which slough to form discrete circumscribed ulcers with raised edges. These lesions can also be appreciated radiographically. The appearance of a “black esophagus” has also been reported with herpes simplex virus (HSV).160,165 Histologic stains of HSV-infected epithelial cells demonstrate multinucleated giant cells, ballooning degeneration, “ground glass” intranuclear Cowdry type A inclusion bodies, and margination of chromatin. Immunohistologic stains using monoclonal antibodies to HSV antigens or in situ hybridization techniques may improve the diagnostic yield in difficult cases by identifying infected cells that lack characteristic morphologic changes. HSV also may be cultured from esophageal tissue, which is more sensitive than routine histology or cytology.

Most patients have self-limited disease paralleling concordant nasolabial herpes, if present, but upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation have been reported.162 Treatment for herpetic esophagitis is the same as other herpes simplex infections in the immunocompetent host, such as prompt initiation of a 7- to 10-day course of orally administered acyclovir or valacyclovir. Occasionally, severe odynophagia necessitates initial treatment with intravenous acyclovir, 250 mg/m2 every eight hours and then changing to oral therapy when the patient can take oral medication. Given the relative rarity of esophageal involvement, however, no outcome data exist specifically on treating esophageal herpes simplex infection.

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a small double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus that infects squamous epithelium of healthy individuals, producing warts and condylomata. The virus can be sexually transmitted. Esophageal infections with HPV are typically asymptomatic. HPV lesions are most frequently found in the mid- to distal esophagus as erythematous macules, white plaques, nodules, or exuberant frond-like lesions.166 In one patient a papilloma developed at a sclerotherapy injection site.167 The diagnosis is made by histologic demonstration of koilocytosis (an atypical nucleus surrounded by a ring), giant cells, or immunohistochemical stains. Treatment is often not necessary, although large lesions have required endoscopic removal. Other treatments such as those using systemic interferon-α (IFN-α), bleomycin, and etoposide have yielded varying results.168 One patient had numerous lesions in the esophagus and upper airway that were unresponsive to all forms of therapy and eventually fatal.169

HPV infection has been implicated as a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma, particularly carcinoma of the uterine cervix. An association between HPV and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus has been demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or in situ DNA hybridization in esophageal tumor specimens from South Africa, northern China, and Alaska.170 In contrast, HPV DNA was not found in or near esophageal squamous cell carcinomas from the continental United States, Europe, Japan, or Hong Kong.171,172

TRYPANOSOMA CRUZI (see also Chapter 109)

Chagas’ disease is the result of progressive destruction of mesenchymal tissues and nerve ganglion cells throughout the body by Trypanosoma cruzi, a parasite endemic to South America. Abnormalities of the heart, esophagus, gallbladder, and intestines are the clinical consequence. Esophageal manifestations may appear 10 to 30 years after the acute infection and typically include difficulty swallowing, chest pain, cough, and regurgitation. Nocturnal aspiration is common. Esophageal manometric recordings are identical to findings in achalasia, although the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure is lower in Chagas’ disease.173 Manometric abnormalities of the esophagus can be found in asymptomatic seropositive patients.174 The putative mechanism is the development of antimuscarinic receptor antibodies in response to the infection.175 A chagasic esophagus may be responsive to nitrates; balloon dilation; or, ultimately, myectomy at the gastroesophageal junction.176 Patients who have intractable symptoms or pulmonary complications secondary to megaesophagus may be candidates for esophagectomy.177 Those with long-standing stasis due to Chagas’ disease often have hyperplasia of esophageal squamous epithelia and are at increased risk for esophageal cancer.

MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS

Most reports of esophageal Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections are from areas of endemic tuberculosis. Esophageal manifestations of tuberculosis are almost exclusively a result of direct extension from adjacent mediastinal structures, but there are well-documented cases of primary esophageal tuberculosis.178,179 The clinical presentation of secondary esophageal tuberculosis is quite different from those of most other causes of infectious esophagitis. Specifically, dysphagia is often accompanied by weight loss, cough, chest pain, and fever. Subsequent complications include bleeding, perforation, and fistula formation.179 Choking on swallowing may be indicative of an underlying fistula between the esophagus and respiratory tract.

Other radiographic findings include displacement of the esophagus by mediastinal lymph nodes and sinus tracts extending into the mediastinum. Endoscopy is often necessary to confirm active tuberculosis; caution is advised to prevent infection of medical staff by aerosolized tubercle bacilli. Endoscopic findings include shallow ulcers, heaped-up lesions mimicking neoplasia, and extrinsic compression of the esophagus.180 Lesions should be biopsied and brushed thoroughly, and specimens should be obtained for acid-fast stain, mycobacterial culture, and PCR, in addition to routine studies. When extrinsic compression is the only esophageal manifestation of tuberculosis, the diagnosis must be confirmed by bronchoscopy, mediastinoscopy, or transesophageal fine-needle aspiration cytologic evaluation.181 Surgery is sometimes required to repair fistulas, perforations, and bleeding ulcers.

TREPONEMA PALLIDUM

Syphilis, which became increasingly prevalent in the United States in the 1990s, can rarely cause esophageal disease in immunocompetent individuals. Earlier literature described gummas, diffuse ulceration, and strictures of the esophagus in tertiary syphilis.182 The diagnosis of syphilitic esophagus should be considered when a patient has an inflammatory stricture and other evidence of tertiary syphilis. Histologic evaluation may show perivascular lymphocytic infiltration; however, specific immunostaining should be done if this diagnosis is a possibility.

OTHER INFECTIONS THAT RARELY INVOLVE THE ESOPHAGUS

Rare viral infections that might involve the esophagus in the immunocompetent adult include herpes zoster and Epstein-Barr virus,183 both of which may produce ulceration. Rare fungal infections of the esophagus include blastomycosis, presenting as an esophageal mass,184 and histoplasmosis, through direct extension of mediastinal adenopathy similar to tuberculosis.185

ACUTE ESOPHAGEAL NECROSIS

Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus) is a rare disorder that is poorly understood. Ischemia is thought to play a role in its pathogenesis.186

Cummings JE, Schwiekert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Brief communications: Atrial-esophageal fistulas after radiofrequency ablation. Ann Int Med. 2006;144:572-4. (Ref 92.)

D’Avila A, Ptaszek LM, Yu PB, et al. Left atrial-esophageal fistula after pulmonary vein isolation. Circulation. 2007;115:e432-3. (Ref 95.)

Donta ST, Engel CCJr, Collins JF, et al. Benefits and harms of doxycycline treatment for Gulf War veterans’ illness. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:85-94. (Ref 2.)

Famularo G, De Simone C. Fatal esophageal perforation with alendronate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3212-13. (Ref 28.)

Grudell ABM, Mueller PS, Viggiano TR. Black esophagus: Report of six cases and review of the literature, 1963-2003. Dis Esophag. 2006;19:105-10. (Ref 160.)

Gurvits GE, Shapis A, Lau N, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: A rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29-38. (Ref 186.)

Kato S, Yamamoto R, Yoshimitsu S, et al. Herpes simplex esophagitis in the immunocompetent host. Dis Esophag. 2005;18:340-4. (Ref 163.)

Kikendall JW. Pill-induced esophageal injury. In: Castell DO, Richter JE, editors. The esophagus. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:572. (Ref 10.)

Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381-91. (Ref 156.)

Macedo G, Azevedo F, Ribeiro T. Ulcerative esophagitis caused by etidronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:250-1. (Ref 33.)

Manning BJ, Winter DC, McGreal G, et al. Nasogastric intubation causes gastroesophageal reflux in patients undergoing elective laparotomy. Surgery. 2001;130:788-91. (Ref 86.)

Nagri S, Hwang R, Anand S, Kurz J. Herpes simplex esophagitis presenting as acute necrotizing esophagitis (“black esophagus”) in an immunocompetent patient. Endoscopy. 2007;39:E169. (Ref 165.)

Reed AR, Michell WL, Krige JE. Mechanical tracheal obstruction due to an intramural esophageal hematoma following endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy. Am Surg. 2001;67:690-2. (Ref 75.)

Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: A randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165-73. (Ref 157.)

Straumann A, Bussmann C, Zuber M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:598-600. (Ref 135.)

1. Carlborg B, Kumlien A, Olsson H. Medikamentella esofagusstrikturer. Lakartidningen. 1978;75:4609.

2. Donta ST, Engel CCJr, Collins JF, et al. Benefits and harms of doxycycline treatment for Gulf War veterans’ illness. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:85.

3. Hey H, Jorgensen F, Sorensen K, et al. Esophageal transit of six commonly used tablets and capsules. BMJ. 1982;285:1717.

4. McCord GS, Clouse RE. Pill-induced esophageal strictures: Clinical features and risk factors for development. Am J Med. 1990;88:512.

5. Whitney B, Croxon R. Dysphagia caused by cardiac enlargement. Clin Radiol. 1972;23:147.

6. Mason SJ, O’Meara TF. Drug-induced esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3:115.

7. Walta DC, Giddens JD, Johnson LF. Localized proximal esophagitis secondary to ascorbic acid ingestion and esophageal motor disorder. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:766.

8. Berkelhammer C, Gutti P. Pill-induced esophagitis within esophageal diverticulae. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:287.

9. Levine MS. Drug-induced disorders of the esophagus. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:3.

10. Kikendall JW. Pill-induced esophageal injury. In: Castell DO, Richter JE, editors. The esophagus. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:572.

11. Bonavina L, DeMeester TR, McChesney L, et al. Drug-induced esophageal strictures. Ann Surg. 1987;206:173.

12. Ribeiro A, DeVault KR, Wolfe JTIII, et al. Alendronate-associated esophagitis: Endoscopic and pathologic features. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:525.

13. Abraham SC, Bhagavan BS, Lee LA, et al. Upper gastrointestinal tract injury in patients receiving Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) in sorbitol: Clinical, endoscopic and histopathologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:637.

14. Ravich WJ, Kashima H, Donner MW. Drug-induced esophagitis simulating esophageal carcinoma. Dysphagia. 1986;1:13.

15. Wong RKH, Kinkendall JW, Dachman AH. Quinaglute-induced esophagitis mimicking an esophageal mass. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:62.

16. Creteur V, Laufer I, Kressel HY, et al. Drug-induced esophagitis detected by double-contrast radiography. Radiology. 1983;147:365.

17. Agha FP, Wilson JA, Nostrand TT. Medication-induced esophagitis. Gastrointest Radiol. 1986;11:7.

18. McCullough RW, Afzal ZA, Saifuddin TNMI, et al. Pill-induced esophagitis complicated by multiple esophageal septa. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:150-2.

19. Froese EH. Esophagitis with clindamycin. S Afr Med J. 1979;56:828.

20. Sutton DR, Gosnold JK. Esophageal ulceration due to clindamycin. BMJ. 1977;1:1598.

21. Smith SJ, Lee AJ, Maddix DS, Chow AW. Pill-induced esophagitis caused by oral rifampin. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:27-31.

22. Bova JG, Dutton NE, Godstein HM, et al. Medication-induced esophagitis: Diagnosis by double-contrast esophagography. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:731.

23. Indorf A, Pegram PS. Esophageal ulceration related to zalcitabine (ddC). Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:133.

24. Edwards P, Turner J, Gold J, et al. Esophageal ulceration induced by zidovudine. Ann Intern Med. 1990;91:27.

25. Hutter D, Akgun S, Ramamoorthy R, et al. Medication bezoar and esophagitis in a patient with HIV infection receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med. 2000;108:684.

26. Yue Q-Y, Mortimer O. Alendronate: Risk for esophageal stricture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1581.

27. Abdelmalek ME, Douglas DD. Alendronate-induced ulcerative esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1282.

28. Famularo G, De Simone C. Fatal esophageal perforation with alendronate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3212.

29. Ryan JM, Kelsey P, Ryan BM, et al. Alendronate-induced esophagitis: Case report of a recently recognized form of severe esophagitis with esophageal stricture: Radiographic features. Radiology. 1998;206:389.

30. de Groen PC, Lubbe DF, Hirsch LJ, et al. Esophagitis associated with the use of alendronate. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1016.

31. Colina RA, Smith M, Kikendall JW, et al. A new probably increasing cause of esophageal ulceration: Alendronate. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:704.

32. Levine J, Nelson D. Esophageal stricture associated with alendronate therapy. Am J Med. 1997;102:489.

33. Macedo G, Azevedo F, Ribeiro T. Ulcerative esophagitis caused by etidronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:250.

34. Lufkin EG, Argueta R, Whitaker MD, et al. Pamidronate: An unrecognized problem in gastrointestinal tolerability. Osteoporosis Int. 1994;4:320.

35. Lanza FL, Rack MF, Li Z, et al. Placebo-controlled, randomized, evaluator-blinded endoscopy study of risedronate vs. aspirin in healthy postmenopausal women. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1663.

36. Perkins AC, Wilson CG, Frier M, et al. Oesophageal transit, disintegration and gastric emptying of a film-coated risedronate placebo tablet in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and normal control subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:115.

37. Lanza FL, Hunt RH, Thomson AB, et al. Endoscopic comparison of esophageal and gastroduodenal effects of risedronate and alendronate in postmenopausal women. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:886.

38. Abraham SC, Cruz-Correa M, Lee LA, et al. Alendronate-associated esophageal injury: Pathologic and endoscopic features. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1152.

39. Schreiber JB, Covington JA. Aspirin-induced esophageal hemorrhage. JAMA. 1988;259:1647.

40. McAndrew NA, Greenway MW. Medication-induced esophageal injury leading to broncho-esophageal fistula. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:379.

41. Kahn LH, Chen M, Eaton R. Over-the-counter naproxen sodium and esophageal injury. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:1006.

42. Lanas A, Bajador E, Serrano P, et al. Nitrovasodilators, low-dose aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:843.

43. Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Risk factors for erosive reflux esophagitis: A case control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:41.

44. Lanas AI, Sousa FL, Ortego J, et al. Aspirin renders the oesophageal mucosa more permeable to acid and pepsin. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:1065.

45. Learmouth I, Weaver PC. Potassium stricture formation of the upper alimentary tract. Lancet. 1976;1:251.

46. Peter JL. Benign esophageal stricture following oral potassium chloride therapy. Br J Surg. 1976;63:698.

47. McCall AJ. Slow-K ulceration of esophagus with aneurysmal left atrium. BMJ. 1975;3:320.

48. Henry JG, Shinner JJ, Martino JH, et al. Fatal esophageal and bronchial artery ulceration caused by solid potassium chloride. Pediatr Cardiol. 1983;4:251.

49. Rosenthal T, Adar R, Militianu J, et al. Esophageal ulceration and oral potassium chloride ingestion. Chest. 1974;65:463.

50. Chesshyre MH, Braimbridge MV. Dysphagia due to left atrial enlargement after Starr valve replacement. Br Heart J. 1972;33:799.

51. Whitney B, Coroxon R. Dysphagia caused by cardiac enlargement. Clin Radiol. 1972;23:147.

52. Boyce HWJr. Dysphagia after open heart surgery. Hosp Pract. 1985;20:40.

53. Abbarah TR, Fredell JE, Ellenz GB. Ulceration by oral ferrous sulfate. JAMA. 1976;236:2320.

54. Stoller JL. Esophageal ulceration and theophylline. Lancet. 1985;2:328.

55. Enzenauer RW, Bass JW, McDonnell JT. Esophageal ulceration associated with oral theophylline. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:261.

56. Oren R, Fich A. Oral contraceptive-induced esophageal ulcer: Two cases and literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1489.

57. Perry PA, Dean BS, Krenclok EP. Drug induced esophageal injury. Clin Toxicol. 1989;27:281.

58. Higuchi K, Ando K, Kim SR, et al. Sildenafil-induced esophageal ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2516.

59. Loft DE, Stubington S, Clark C, et al. Esophageal ulcer caused by warfarin. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:258.

60. Hunert H, Ottenjann R. Drug-induced esophageal ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1979;25:41.

61. Maekawa T, Ohji G, Inoue R, et al. Pill-induced esophagitis caused by lansoprazole. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:790.

62. Yamaoka K, Takenawa H, Tajiri K, et al. A case of esophageal perforation due to a pill-induced ulcer successfully treated with conservative measures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1044.

63. Maroy B, Moullot P. Esophageal burn due to chlorazepate dipotassium (Tranxene). Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:240.

64. Al Mahdy H, Boswell GV. Captopril-induced esophagitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;34:95.

65. Saint-Marc T, Fournier F, Touraine JL, Marneff E. Uvula and esophageal ulcerations with foscarnet. Lancet. 1992;340:970.

66. Fiedorek SC, Casteel HB. Pediatric medication-induced focal esophagitis. Clin Pediatr. 1988;27:455.

67. Sharara AI. Lozenge-induced esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:622.

68. Shubert MM, Peterson DE, Lloid ME. Oral complications. In: Thomas ED, Blume KG, Forman SJ, et al, editors. Hematopoietic cell transplantation. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Science; 1999:751.

69. Wang WS, Chiou TJ, Liu JH, et al. Vincristine-induced dysphagia suggesting esophageal motor dysfunction: A case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:515.

70. Mosimann F, Bronnimann B. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus complicating sclerotherapy for varices. Gut. 1994;35:130.

71. Stiegman GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1527.

72. Korula J, Pandya K, Yamada S. Perforation of esophagus after endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy: Incidence and clues to pathogenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:324.

73. Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:280.

74. Sidhu SS, Bal C, Karak P, et al. Effect of endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy on esophageal motor functions and gastroesophageal reflux. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1363.

75. Reed AR, Michell WL, Krige JE. Mechanical tracheal obstruction due to an intramural esophageal hematoma following endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy. Am Surg. 2001;67:690.

76. Chen TA, Lo GH, Lai KH. Spontaneous rupture of iatrogenic intramural hematoma of esophagus during endoscopic sclerotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:850.

77. Tanoue K, Hashizume M, Ohta M, et al. Development of early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:792.

78. Mistry FP, Sreenivasa D, Narawane NM, et al. Vagal dysfunction following endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998;17:22.

79. Berner JS, Gaing AA, Sharma R, et al. Sequelae after esophageal variceal ligation and sclerotherapy: A prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:852.

80. Grande L, Planas R, Lacima G, et al. Sequential esophageal motility studies after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: A prospective investigation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:36.

81. Kinoshita Y, Kitajima N, Itoh T, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:282.

82. Snady H, Rosman AS, Korsten MA. Prevention of stricture formation after endoscopic sclerotherapy of esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:377.

83. Yang WG, Hou MC, Lin HC, et al. Effect of sucralfate granules in suspension on endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy induced ulcer: Analysis of the factors determining ulcer healing. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:225.

84. Pulanic R, Vrhovac B, Jokic N, et al. Prophylactic administration of ranitidine after sclerotherapy of esophageal varices. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1991;29:347.

85. Garg PK, Sidhu SS, Bhargava DK. Role of omeprazole in prevention and treatment of postendoscopic variceal sclerotherapy esophageal complications: Double-blind randomized study. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1569.

86. Manning BJ, Winder DC, McGreal G, et al. Nasogastic intubation causes gastroesophageal reflux in patients undergoing elective laparotomy. Surgery. 2001;130:788.

87. Kuo B, Castell DO. The effect of nasogastric intubation on gastroesophageal reflux: A comparison of different tube sizes. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1804.

88. Stoppacher R, Teggatz JR, Jentzen JM. Esophageal and pharyngeal injuries associated with the use of the esophageal-tracheal Combitube. J Forensic Sci. 2004;49:586.

89. Geha AS, Seegers JV, Kodner IJ, Lefrak S. Tracheoesophageal fistula caused by cuffed tracheal tube: Successful treatment by tracheal resection and primary repair with four-year follow-up. Arch Surg. 1978;113:338.

90. Shapira OM, Aldea GS, Kupferschmid J, Shemin RJ. Delayed perforation of the esophagus by a closed thoracostomy tube. Chest. 1993;104:1897.

91. Han YY, Cheng YJ, Liao WW, et al. Delayed diagnosis of esophageal perforation following intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during valvular replacement: A case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 2003;41:81.

92. Cummings JE, Schwiekert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Brief communications: Atrial-esophageal fistulas after radiofrequency ablation. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:572-4.

93. Ripley KL, Gage AA, Olsen DB, et al. Time course of esophageal lesions after catheter ablation with cryothermal and radiofrequency ablations: Implication for atrio-esophageal fistula formation after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electro. 2007;18:642-2.

94. Malamis AP, Kirshenbaum KJ, Nadimpalli S. CT radiographic findings: Atrio-esophageal fistula after transcatheter percutaneous ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Imag. 2007;22:188-91.

95. D’Avila A, Ptaszek LM, Yu PB, et al. Left atrial-esophageal fistula after pulmonary vein isolation. Circulation. 2007;115:e432-3.

96. Sonmez B, Demirsoy E, Yagan N, et al. A fatal complication due to radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: Atrioesophageal fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:281-3.

97. Beal SI, Pottmeyer EW, Spisso JM. Esophageal perforation following external blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1988;28:1425.

98. Gill SS, Dierking JM, Nguyen KT, et al. Seatbelt injury causing perforation of the cervical esophagus: A case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2004;70:32.

99. Orlando ER, Caroli E, Ferrante L. Management of the cervical esophagus and hypopharynx perforations complicating anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2003;28:E290.

100. Back MR, Baumgartner FJ, Klein SR. Detection and evaluation of aerodigestive tract injuries caused by cervical and transmediastinal gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 1997;42:680.

101. Kanne JP, Stern EJ, Pohlman TH. Trauma cases from Harborview Medical Center. Tracheoesophageal fistula from a gunshot wound to the neck. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:212.

102. Winter RP, Weigelt JA. Cervical esophageal trauma. Incidence and cause of esophageal fistulas. Arch Surg. 1990;125:851.

103. Madiba TE, Muckart DM. Penetrating injuries to the cervical esophagus: Is routine exploration mandatory? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:162.

104. Ngakane H, Muckart DJ, Luvuno FM. Penetrating visceral injuries of the neck: Results of a conservative management policy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:908.

105. Naude GP, van Zyl F, Bongard FS. Gunshot injuries of the lower esophagus. Injury. 1998;29:95.

106. Back MR, Baumgartner FJ, Klein SR. Detection and evaluation of aerodigestive tract injuries caused by cervical and transmediastinal gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 1997;42:680.

107. Glatterer MSJR, Toon RS, Ellestad C, et al. Management of blunt and penetrating external esophageal trauma. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 1985;25:784.

108. Bufkin BL, Miller JIJr, Mansour KA. Esophageal perfora-tion: Emphasis on management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1447.

109. Asensia JA, Chahwan S, Forno W, et al. Penetrating esophageal injuries: Multicenter study of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:289.

110. Siersema PD, Homs MY, Haringsma J, et al. Use of a large-diameter metallic stents to seal traumatic nonmalignant perforations of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:356.

111. Mallory GK, Weiss SW. Hemorrhages from lacerations of the cardiac orifice of the stomach due to vomiting. Am J Med Sci. 1929;178:506-12.

112. Michel L, Serrano A, Malt RA. Mallory-Weiss syndrome: Evaluation of diagnostic and therapeutic patterns over two decades. Ann Surg. 1980;192:716-21.

113. Watts HD. Lesions brought on by vomiting: the effects of hiatus hernia on the site of injury. Ann Surg. 1976;145:30-3.

114. Ziad Y, Johnson DA. The spectrum of spontaneous and iatrogenic esophageal injury: perforations, Mallory-Weiss tears, and hematomas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:306-17.

115. Graham DY, Schwartz JT. The spectrum of Mallory-Weiss tear. Medicine. 1978;57:307-18.

116. Brinberg DE, Stein J. Mallory-Weiss tear with colonic lavage. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:894-5.

117. Norfleet RG, Smith GH. Mallory Weiss syndrome after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:569-72.

118. Watts HD. Mallory-Weiss tear occurring as a complication of endoscopy. Gastrointest Endsosc. 1976;22:171-2.

119. DeVries AJ, van der Maaten JMAA, Laurens RRP. Mallory-Weiss tear following cardiac surgery: Transesophageal echoprobe or nasogastric tube? Br. J Anesth. 2000;84:646-9.

120. Hiromichi F, Shigefumi S, Toshihiko S, et al. Mallory-Weiss tear complicating intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. Circ J. 2003;67:357-8.

121. St, John DJB, Masterton JP, Yeomans ND, Dudley HAF. The Mallory-Weiss syndrome. BMJ. 1974;1:140-3.

122. Knauer CM. Mallory-Weiss syndrome: Characterization of 75 Mallory-Weiss lacerations in 538 patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:5-80.

123. Skok P. Fatal hemorrhage from a giant Mallory-Weiss tear. Endoscopy. 2003;35:635.

124. Llach J, Elizalde I, Guervara C, et al. Endoscopic injection therapy in bleeding Mallory-Weiss syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:679-81.

125. Higuchi N, Akahoshi K, Sumida Y, et al. Endoscopic band ligation therapy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding related to Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1431-4.

126. Gunay K, Cabioglu N, Barbaros U, et al. Endoscopic ligation for patients with active bleeding Mallory-Weiss tears. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1305-7.

127. Park C-H, Mini S-W, Sohn Y-H, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of endoscopic band ligation vs. epinephrine injection for actively bleeding Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:22-7.

128. Technology Assessment Committee, ASGE. Endoscopic clip application devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:746-50.

129. Fisher RG, Schwartz JT, Graham DY. Angiotherapy with Mallory-Weiss tear. Am J Roentgenol. 1980;134:679-84.

130. Korn O, Onate JC, Lopez R. Anatomy of Boerhaave syndrome. Surgery. 2007;141:222-8.

131. Curci JJ, Horman MJ. Boerhaave’s syndrome: The importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Surg. 1976;353:401-8.

132. Cappell MS, Sciales C, Biempica L. Esophageal perforation at a Barrett’s ulcer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:663-5.

133. Cronstedt JL, Bouchama A, Hainau B, et al. Esophageal perforation in herpes simplex esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:124-7.

134. Adkins MSA, Raccuai JS, Acinapura AJ. Esophageal perforation in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;50:299-300.

135 Straumann A, Bussmann C, Zuber M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:598-600.

136. Henderson JAM, Peloquin AJM. Boerhaave revisited: Spontaneous esophageal perforation as a diagnostic masquerader. Am J Med. 1989;86:559-67.

137. Ghassemi KF, Rodriguez HJ, Vesga L, et al. Endoscopic treatment of Boerhaave syndrome using a removable self-expandable plastic stent. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:863-4.

138. Meulman N, Evans J, Watson A. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus: A report of three cases and review of the literature. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:190-3.

139. Spanier BW, Bruno MJ, Meijer JL. Spontaneous esophageal hematoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:755-6.

140. Horan P, Drake M, Patterson RN, et al. Acute onset of dysphagia associated with an intermural esophageal hematoma in acquired hemophilia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:205-7.

141. Kwan K-L, Law S, Wong K-H, Kowk K-F. Esophageal hematoma: A masquerade of rare occurrence. Endoscopy. 2006;38:E29.

142. Borrie J, Sheat J. Spontaneous intramural esophageal perforation. Thorax. 1970;25:294-300.

143. Tong M, Hung W-K, Law S, et al. Esophageal hematoma. Dis Esoph. 2006;19:200-2.

144. Lu MS, Liu YH, Liu HP, et al. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:343-5.

145. Enns R, Brown JA, Halparin L. Intramural esophageal hematoma: A diagnostic dilemma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:757-9.

146. Shay SS, Berendson RA, Johnson LF. Esophageal hematoma: Four new cases, a review, and a proposed etiology. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:1019-24.

147. Biagi G, Cappelli G, Propersi L, Grossi A. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Thorax. 1983;39:394-5.

148. Sen A, Lea RE. Spontaneous esophageal hematoma: A review of the difficult diagnosis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:293-5.

149. Herbetko J, Delany D, Obilvie BC, Blaquiere RM. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus: Appearance on computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 1991;44:327-8.

150. Kamphius AG, Baur CH, Freling NJ. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: Appearance on magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13:1037-42.

151. Geller A, Gostout CJ. Esophageal gastric hematoma mimicking a malignant neoplasm: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. May Clin Proc. 1998;73:342-5.

152. Badarinarayanan G, Gowriskankar R, Muthulakshmi K. Esophageal candidiasis in non-immune suppressed patients in a semi-urban town, southern India. Mycopathologia. 2000;149:1.

153. Anderson LI, Frederiksen HJ, Appleyard M. Prevalence of esophageal Candida colonization in a Danish population, with special reference to esophageal symptoms, benign esophageal disorders, and pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:389.

154. Hendel L, Svejgaard E, Walsoe I, et al. Esophageal candidosis in progressive systemic sclerosis: Occurrence, significance, and treatment with fluconazole. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1182.

155. Simon MR, Houser WL, Smith KA, et al. Esophageal candidiasis as a complication of inhaled corticosteroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1997;79:333.

156. Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol. 2006;131:1381-91.

157. Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: A randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165-73.

158. Baehr PH, McDonald GB. Esophageal infections: Risk factors, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:509.

159. Levine MS. Other esophagitides. In: Gore RM, Levine MS, Laufer I, editors. Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994:423.

160. Grudell ABM, Mueller PS, Viggiano TR. Black esophagus: Report of six cases and review of the literature, 1963-2003. Dis Esophag. 2006;19:105-10.

161. Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Pictorial glossary of double contrast radiology. In: Gore RM, Levine MS, Laufer I, editors. Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994:53.

162. Sethumadavan S, Ramanathan J, Rammouni R, et al. Herpes simplex esophagitis in the immunocompetent host: An overview. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2264.

163. Kato S, Yamamoto R, Yoshimitsu S, et al. Herpes simplex esophagitis in the immunocompetent host. Dis Esophag. 2005;18:340-4.

164. Lee B, Caddy G. A rare cause of dysphagia: Herpes simplex esophagitis. W J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2756-7.

165. Nagri S, Hwang R, Anand S, Kurz J. Herpes simplex esophagitis presenting as acute necrotizing esophagitis (“black esophagus”) in an immunocompetent patient. Endoscopy. 2007;39:E169.

166. Ravakhah K, Midamba F, West BC. Esophageal papillomatosis from human papilloma virus proven by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Med Sci. 1998;316:285.

167. Yamada Y, Ninomiya M, Kato T, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16-positive esophageal papilloma at an endoscopic injection sclerotherapy site. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:550.

168. Leventhal BG, Kashima HK, Mounts P. Long-term response of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis to treatment with lymphoblastoid interferon-alfa-n1. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:613.

169. Hording M, Hording U, Daugaard S. Human papilloma virus type 11 in a fatal case of esophageal and bronchial papillomatosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1989;21:229.

170. Sur M, Cooper K. The role of the human papilloma virus in esophageal cancer. Pathology. 1998;30:348.

171. Poljak M, Cerar A, Seme K. Human papillomavirus infection in esophageal carcinomas: A study of 121 lesions using multiple broad-spectrum polymerase chain reactions and literature review. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:266.

172. Saegusa M, Hashimura M, Takano Y, et al. Absence of human papillomavirus genomic sequences detected by the polymerase chain reaction in esophageal and gastric carcinomas in Japan. Mol Pathol. 1997;50:101.

173. Dantas RO, Godoy RA, de Oliveria RB. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure in Chagas’ disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:508.

174. Dantas RO, Deghaide NH, Donadi EA. Esophageal manometric and radiologic findings in asymptomatic subjects with Chagas’ disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:245.

175. Goin JC, Sterin-Borda L, Bilder CR, et al. Functional implications of circulating muscarinic cholinergic receptor autoantibodies in chagasic patients with achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:798.

176. Pinotti HW, Felix VN, Zilberstein B, et al. Surgical complications of Chagas’ disease: Megaesophagus, achalasia of the pylorus, and cholelithiasis. World J Surg. 1991;15:198.

177. Herbella FA, Del Grande JC, Lourenco LG, et al. Late results of Heller operation and fundoplication for the treatment of the megaesophagus: Analysis of 83 cases. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1999;45:317.

178. Jain S, Kumar N, Das DK, et al. Esophageal tuberculosis: Endoscopic cytology as a diagnostic tool. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:1085.

179. Fang HY, Lin TS, Cheng CY, et al. Esophageal tuberculosis: A rare presentation with massive hematemesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2344.

180. Perdomo JA, Naomoto Y, Haisa M, et al. Tuberculosis of the esophagus. Dis Esoph. 1998;11:72.

181. Kochhar R, Sriram PV, Rajwanshi A, et al. Transesophageal endoscopic fine-needle aspiration cytology in mediastinal tuberculosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:271.

182. Stone J, Friedberg SA. Obstructive syphilitic esophagitis. JAMA. 1961;177:711.

183. Tilbe KS, Lloyd DA. A case of viral esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:494.

184. Khandekar A, Moser D, Fidler WJ. Blastomycosis of the esophagus. Ann Thor Surg. 1980;30:76.

185. Marshall JB, Singh R, Demmy TL, et al. Mediastinal histoplasmosis presenting with esophageal involvement and dysphagia: Case study. Dysphagia. 1995;10:53.

186. Gurvits GE, Shapis A, Lau N, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: A rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29-38.