Erythema Multiforme, Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

History

In 1866, the Austrian dermatologist Ferdinand von Hebra first described erythema multiforme as a self-limited cutaneous disease characterized by multiform skin lesions.1 In association with the erythematous skin lesions, his findings included a severe stomatitis and purulent conjunctivitis. In 1922, two American pediatricians, Stevens and Johnson, described two boys with a more severe mucocutaneous disease with ophthalmologic manifestations, naming the disease eruptive fever with stomatitis and ophthalmia.2 This nomenclature was not adopted. However, since that time, erythema multiforme major has been most commonly referred to as Stevens–Johnson syndrome. In 1950, Thomas suggested the division of erythema multiforme into two forms: minor (von Hebra) and major (SJS).3 In 1956, Lyell introduced the term toxic epidermal necrolysis, a condition characterized by more extensive skin loss in conjunction with mucous membrane involvement.4

Classification

There was confusion in the nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for the erythema multiforme spectrum of diseases until an international classification was adopted in 1993.5 Traditionally, erythema multiforme was divided into minor and major forms, with the minor form only involving skin, with no or minimal mucous membrane involvement and not involving the eye. Table 30.1 outlines the diagnostic criteria for bullous skin diseases.6 Although the terms EM major and SJS are often used interchangeably, international collaborators have now differentiated them by their etiology and pattern of cutaneous lesions.7 The major etiologic factor for EM major (or bullous EM) is herpes simplex virus (HSV), compared to drug-induced SJS. An international consensus collaboration further classified the overlap between SJS and TEN. They defined five categories based on the pattern of skin lesions and extent of epidermal detachment as shown in Table 30.2.5

Table 30.1

Diagnostic Criteria for Bullous Skin Diseases

Target (iris) lesions (typical or atypical)

Individual lesions < 3 cm in diameter

No or minimal mucous membrane involvement

Biopsy specimen compatible with EM minor

STEVENS–JOHNSON SYNDROME (ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME MAJOR)

< 20% of body area involved in first 48 hours

> 10% of body area involvement

Target (iris) lesions (typical or atypical)

Individual lesions < 3 cm in diameter (lesions may coalesce)

Mucous membrane involvement (at least 2 areas)

Biopsy specimen compatible with EM major

Bullae and/or erosions over 20% of body area

Bullae develop on erythematous base

Occurs on non-sun-exposed skin

Skin peels off in > 3-cm sheets

Mucous membrane involvement frequent

(Adapted from Chan HL, Stern RS, Arndt KA, et al. The incidence of erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. A population-based study with particular reference to reactions caused by drugs among outpatients. Arch Dermatol 1990;126:43–7.)

Table 30.2

Proposed Classification of Cases in the Spectrum of Severe Bullous EM

EM, erythema multiforme; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

(Adapted from Bastuji-Garin. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:92–6.)

Incidence

Although EM/SJS/TEN are rare conditions, they are important because they cause high mortality and morbidity. Chan (USA) reported an overall incidence of these diseases at 4.2 per million person-years (TEN 0.5 per million person-years),6 and Rzany (Germany) reported an overall incidence of 1.89 per million person-years.8 Schöpf (Germany) reported an incidence of SJS at 1.1 per million person-years and incidence of TEN at 0.93 per million person-years.9 Roujeau (France) reported an incidence of TEN at 1.2 to 1.3 per million person-years.10 The reported mortality rate is 1% for EM, 1% to 7% for SJS, and 30% to 45% for TEN.9–11 Both the incidence and the mortality appear to be higher in immunocompromised patients with these risks correlated with weaker immune function.12 EM is more common in males, whereas TEN is more common in women, with a ratio ranging from 1.5 : 1 to 2.0 : 1.9–11 Although these conditions can occur at any age, EM and SJS tends to occur in younger patients in their second to third decades, whereas TEN occurs in older patients in their fifth to seventh decades.9–11

Etiology

Drugs and infections are the most common inciting causes of disease, as shown in Table 30.3. Drug-related reactions typically begin within 3 weeks of initiation of therapy. In cases of re-exposure to the drug, the reaction may begin within hours of restarting the therapy.6 TEN is usually drug-related. Drugs are an important cause of SJS, but infections, or a combination of infections and drugs has also been implicated. Infections, especially viral, are the most common cause of EM. In large epidemiology studies, drugs accounted for 89% to 95.5% of cases of TEN,9,10 54% to 64% of cases of SJS,9,11 and 18% for EM major.11 In the international prospective SCAR (severe cutaneous adverse reactions) study, recent or recurrent herpes was the principal risk factor for EM major (etiologic fractions of 29% and 17%, respectively) and had a role in SJS (etiologic fractions of 6% and 10%) but not in overlap cases or TEN.11 Mycoplasma pneumoniae has also been associated with EM Major in several studies.11,13

Table 30.3

Etiologies of Stevens–Johnson Syndrome

| Etiologic agent | Most frequently described |

| Drugs | Sulfas, NSAIDs, antiepileptics, barbiturates, allopurinol, tetracyclines, antiparasitics |

| Viral | HIV, herpes simplex, Epstein–Barr, influenza, coxsackie, lymphogranuloma venereum, variola |

| Bacterial | Mycoplasma pneumonia, typhoid, tularemia, diphtheria, group A streptococci |

| Fungal | Dermatophytosis, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis |

| Protozoal | Trichomoniasis, plasmodium |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

(Adapted from Hazin R, Ibrahimi OA, Hazin MI, Kimyai-asadi A. Stevens–Johnson syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med 2008;40:129–38.)

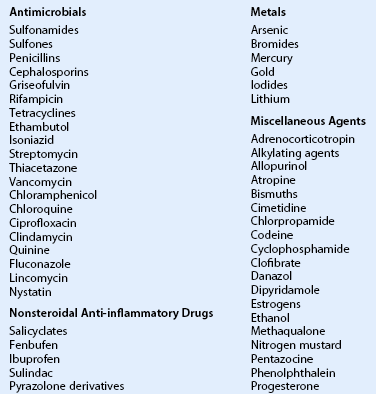

In the SCAR study, the use of antibacterial sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, oxicam nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), allopurinol, chlormezanone, and corticosteroids were associated with large increases in the risk of SJS or TEN.14 However, it is important to note that these reactions are rare, since for each of these drugs the excess risk did not exceed five cases per million users per week. Among drugs usually used for months or years, the increased risk was confined largely to the first 2 months of treatment. Table 30.4 lists drugs that have been associated with these diseases.

Table 30.4

Drugs Associated with EM/SJS/TEN

(Adapted from Palmon et al. Cornea. 3rd ed. Elsevier 2011. p. 604.)

Pathogenesis

The exact pathophysiologic mechanism of EM/SJS/TEN remains unknown. Prevailing evidence indicates an immune-mediated response, in particular those mediated by memory cytotoxic T cells, to drugs and infections. Histologically, keratinocyte death occurs from extensive apoptosis.15 The proposed initiating mechanism involves the interaction between Fas and Fas ligand (FasL), which is either membrane bound on keratinocytes or soluble.16 Activation of the Fas signaling cascade leads to widespread keratinocyte apoptosis and subsequent epithelial necrosis. It has been suggested that soluble FasL is secreted by peripheral blood mononuclear cells and is elevated in EM and TEN patients.17 Other studies have also linked perforin, a pore-making monomeric granule released from natural killer T lymphocytes, which is thought to initiate the keratinolysis seen early in the development of SJS.18 Granulysin has also been implicated as a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in SJS/TEN. Granulysin levels are much higher in patients with SJS/TEN, compared to healthy controls, and also correlate with clinical severity.19

Genetic factors may also play a role in the development of erythema multiforme disorders. Slow acetylators and those taking medications, such as azoles, protease inhibitors, serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors, and quinolones are at increased risk of developing SJS. The reduced rate of acetylation causes the accumulation of reactive metabolites that induce cell-mediated cytotoxic reactions against the epidermis, resulting in keratinocyte apoptosis.12

In studies in Western populations,14,20 antibiotics, particularly sulfonamides, are the most common drug trigger. In the largest Asian study by Chang et al.,13 anticonvulsants, particularly carbamazepine, and allopurinol were the most common drug triggers. A study by Chung et al.21 found a strong association in Han Chinese between the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B*1502 and SJS induced by carbamazepine. Another study showed that HLA-B*5801 is highly associated with allopurinol-induced SJS/TEN.22 These associations suggest the importance of pharmacogenetic mechanisms on the risk of developing SJS/TEN.

Histopathology

The initial diagnosis of EM/SJS/TEN is based on clinical presentation; however, skin biopsies should be taken for both routine histopathology and direct immunofluorescence in order to distinguish these conditions from autoimmune blistering disorders. The typical histopathology of EM/SJS/TEN is characterized by vacuolization of epidermal cells and necrosis of keratinocytes within the epidermis, along with dermoepidermal detachment and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration.23 The dermal infiltrate is more pronounced in EM major, compared to SJS or TEN.24 In TEN, subepidermal blistering associated with full-thickness epidermal necrosis occurs.

Clinical Findings

Systemic Features

Mucous membrane involvement occurs in more than 90% of affected patients, and the absence of such lesions should cast doubt on the diagnosis. There is no correlation between the extent and severity of mucous membrane erosions and the extent of epidermal detachment.5,8 Painful erosions of the mucous membrane may affect the lip, oral cavity, conjunctiva, nasal cavity, urethra, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract. Mucous membrane ulceration can result in both short-term dysfunction and morbidity, and lead to long-term complications, due to fibrosis and stricture formation. In the study by Chang et al.13 the most common sites of mucosal involvement were the mouth (72%), eye(s) (60%), genitalia (37%), and anus (8%). Mucous membrane erosions sometimes persist for months after the reparation of the epidermis and may leave atrophic scars.

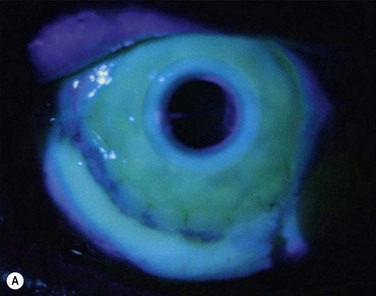

EM/SJS/TEN skin lesions have characteristic patterns and are described in Table 30.2 and shown in Figure 30.1.11 The rash of EM is predominantly on the extremities, including the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet, and on the extensor surface of the forearms, legs, palms and soles.11 Typical target lesions are < 3 cm in diameter, with a regular round shape, well-defined border, and at least three different zones, i.e. two concentric rings around a central disc (Fig. 30.1A). Raised atypical targets are round, edematous, palpable lesions, reminiscent of EM but with only two zones and/or a poorly defined border.

The rash in SJS consists of flat atypical target lesions and erythematous macules that then develop central necrosis to form vesicles, bullae, and areas of denudation on the face, trunk, and extremities. Flat atypical targets are round, non-palpable lesions reminiscent of EM but with only two zones and/or a poorly defined border. Macules are non-palpable, erythematous or purpuric spots with irregular shape and size, and often confluent. Blisters often occur on all or part of the macule (Fig. 30.1B).

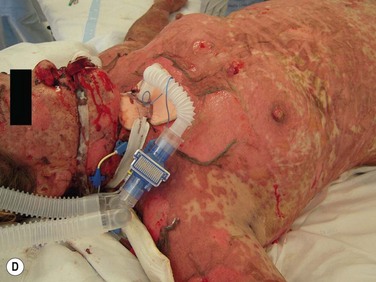

In TEN, the cutaneous lesions begin suddenly with burning and painful red skin, often symmetrically distributed on the face and chest that rapidly extends over the skin surface, including the trunk and proximal extremities. The maximal extension of the lesions is obtained in 3 to 4 days, and sometimes in a few hours.5,8 The hallmark of TEN is a widespread necrosis and detachment of full-thickness epidermis (Figs 30.1C and 30.1D). A positive Nikolsky’s sign may be present, where there is detachment of the full-thickness epidermis when light lateral pressure is applied with the examining finger. Re-epithelialization of the epidermis begins about 1 week after onset of the skin lesions, and most of the skin surface is re-epithelialized in 2 to 3 weeks.

Death usually results from sepsis or multi-organ failure. In the Power et al.20 and Chang et al.13 studies, the most frequent causes of mortality were overwhelming sepsis, respiratory failure, and renal failure. The SCORTEN (TEN-specific severity of illness score) scale25,26 was developed as a tool to predict the severity of the disease and risk of mortality, with prognostic factors, including age, amount of body surface area involved, heart rate, and renal function (Table 30.5).

Table 30.5

SCORTEN Scale: Prognostic Factors for SJS and TEN

| Variable | Value |

| Age | > 40 years |

| Malignancy | Yes |

| Body surface area detached | > 10% |

| Heart rate | > 120 per minute |

| Serum urea | > 10 mmol/L |

| Serum glucose | > 14 mmol/L |

| Serum bicarbonate | < 20 mmol/L |

(Adapted from Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2006;126:272–6.)

Ocular Features

Acute ocular complications develop in over half (i.e. 50% to 81%) of patients hospitalized for SJS and TEN, and 25% of these exhibit severe involvement.13,20 Chronic ocular sequelae occur in up to 35% patients with blinding corneal damage being the most severe long-term complication for survivors.27 In the Power et al. study,20 ocular involvement was seen in 9% of patients with EM, 50% of patients with TEN, and 69% of patients with SJS. Similarly, in the Chang et al. study,13 ocular involvement was more frequent in TEN (66.7%) and SJS (81.3%) than in those with EM (22.7%).

Acute Ocular Features

The acute stage may involve the entire ocular surface, including the eyelids, conjunctiva, and cornea. Initially, the eyelids may be swollen and erythematous, with crusting and ulceration of the lid margin and tarsal conjunctiva. A non-specific conjunctivitis usually occurs at the same time or may precede the onset of the skin lesions, and its severity usually parallels that of the skin lesions.20 More severe involvement can result in pseudomembranous or membranous conjunctivitis. Secondary purulent bacterial conjunctivitis may occur. Conjunctival vesicles are rare. The acute inflammation may rapidly produce scarring, causing symblepharon and ankyloblepharon formation, and fornix foreshortening. In the acute stage, corneal epithelial defects may occur and these may be uncommonly complicated by corneal infiltrates and rarely by corneal perforation. Acute uveitis is uncommon but can occur. The initial eye findings usually last only 2 to 3 weeks.28

Power et al.20 classified severity of ocular involvement as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild involvement was defined as complications requiring routine eye care with full resolution prior to hospital discharge: lid edema, and conjunctival injection and chemosis. Moderate involvement included specific ocular complications that required specific treatment with near complete resolution of active disease upon discharge: conjunctival membrane formation, corneal epithelial loss < 30%, evidence of corneal ulceration or corneal infiltrates. Severe complications included sight-threatening disease, ongoing ocular inflammation with reduced vision, and the need for specific ongoing care after discharge: conjunctival fornix foreshortening, symblepharon formation, and ongoing active corneal disease at the time of discharge. Chang et al.13 used the same classification system and they both found that ocular involvement was not only more frequent but also more severe in SJS and TEN, compared to EM. Power et al. also found that the use of systemic corticosteroids had no effect on the incidence or the severity of ocular manifestations.

Chronic Ocular Features

Chronic ocular features include cicatrizing changes of the conjunctiva and eyelids, severe dry eye, and ocular surface failure. Corneal damage is the most severe long-term complication for survivors of SJS and TEN. These late features may not only result from severe ocular inflammation during the acute phase, but may also be a result of later recurrent episodes of conjunctival inflammation, and perpetuated by the severe dry eye and eyelid pathologies.29,30

Conjunctival inflammation and scarring may cause foreshortening of the fornices, symblepharon, ankyloblepharon, distichiasis, trichiasis, entropion or ectropion. Disorders of the lid–lash complex may cause microtrauma and perpetuate chronic inflammation through the mechanical rubbing of lashes against the ocular surface.30 Ectropion or lagophthalmos can cause exposure keratopathy and further exacerbate the extremely dry ocular surface. Severe dry eye results from conjunctival goblet cell destruction, fornix foreshortening and destruction of the aqueous-secreting glands of Wolfring and Krause, lacrimal gland ductule scarring, and meibomian gland dysfunction.

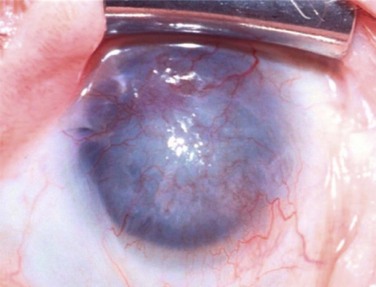

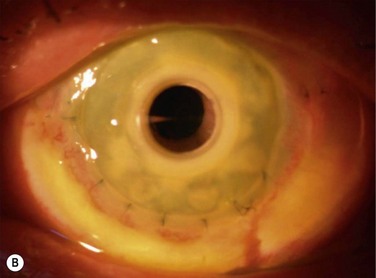

Corneal involvement includes chronic epitheliopathy, persistent epithelial defects, fibrovascular pannus formation, stromal scarring and neovascularization, conjunctivalization, and in severe cases keratinization of the surface (Fig. 30.2). Keratinization also occurs on the posterior lid margin and tarsal conjunctiva, further abrading the ocular surface. Ocular surface failure may appear early as a consequence of the acute stage of disease, or can manifest several years later.30 Destruction of the limbus during the acute phase of the disease may cause partial limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD), but leave enough transient amplifying cells to maintain a normal corneal epithelium for some time. Further destruction of the remaining stem cells by chronic inflammation may cause late stem cell failure.

Recurrent Disease

Most people do not take the inciting drug again; however, in the Chang et al. study,13 recurrences of EM/SJS/TEN occurred in six cases (2.4%) from 3 months to 6 years after the first attack. All initial and recurrent attacks were attributed to drugs, of which three recurrences occurred because the cause of the initial episode had not been recognized. Therefore, great care should be taken to document all medications associated with an episode of EM/SJS/TEN, and patients need to be acutely aware of the inciting medications to avoid future exposure. In other studies, most recurrences were attributable to herpes simplex virus infections. Of the 552 patients in the SCAR study,11 51 (9%) were recurrent. Recurrence rates were higher in EM (30%), compared to SJS (3%) and TEN (3%), due to the association of EM with herpes simplex virus. Prevention by oral antiviral drugs should be considered in cases of recurrent EM, due to herpes simplex virus.31 Recurrence episodes of conjunctival inflammation not associated with external factors may occur.29,32

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the dermatological manifestations of EM/SJS/TEN is broad, due to the varying presentations of the skin lesions and unknown etiology in some cases. The most common diagnoses mistaken for these disorders are staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, exfoliative dermatitis, autoimmune bullous diseases, and chemical/thermal burns.12 It is critical to distinguish SJS and TEN from staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and toxic shock syndrome, which are both bacterial in nature and require immediate appropriate antibiotic therapy to arrest release of the exotoxins responsible for the disease.

Management

Effective management of EM/SJS/TEN involves prompt recognition of the disease, and identification and immediate cessation of all potential offending agents. Immediate cessation of the involved medication reduces mortality and improves prognosis.33 Comprehensive treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach with specialized nursing and medical care to address the complex, systemic response to the disease. Supportive care involves a similar therapeutic protocol as used in burns management: warming of the environment, minimizing transepidermal fluid loss, treatment of electrolyte imbalances, administration of high-calorie nutrition and intravenous fluids, and prevention of sepsis.12 For more extensive cutaneous involvement, early referral to a burns unit reduces the risk of infection, mortality, and length of hospitalization significantly.34,35 The largest trial showed a mortality of 29.8% after transfer to a burns unit with 7 days versus 51.4% (p < 0.05) after 7 days in TEN patients.35 Although sepsis is a major source of mortality, prophylactic systemic antibiotics are not recommended and should be reserved for culture-proven sepsis.12

Skin lesions should be treated with antimicrobial materials, such as copper sulfate, silver nitrate or sulfadiazine cream (which contains sulfonamide and may cross-react with sulfonamide antibiotics) to improve barrier function and to prevent infection.36 Biologic dressings, such as cadaver or porcine skin have also been used.36 Nanocrystalline silver dressings, which serve as an antimicrobial agent and is released for up to 7 to 14 days, have been shown to be beneficial and reduce the frequency of painful dressing changes.37

No treatment modality has been established as the gold standard for patients with EM/SJS/TEN. Given the immune-mediated background of these diseases, treatment with immunosuppressive medication should be expected to be beneficial; however, its use has met with intense debate over the years. Corticosteroids, while beneficial in many other acute inflammatory disorders, are controversial in EM/SJS/TEN. Other immunosuppressants, such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, infliximab, azathioprine, methotrexate, and plasmapheresis have also been tried in small case series.36 However, the efficacy of these agents in the treatment of EM/SJS/TEN has not been demonstrated by any controlled clinical trial.

Several studies have shown that corticosteroid use is detrimental in the treatment of SJS or TEN, resulting in increased mortality and morbidity, most commonly infection and gastrointestinal bleeding.34,38,39 Systemic steroids may also mask early signs of sepsis, impair wound healing, and prolong recovery. However, a large retrospective review of 281 patients enrolled in EuroSCAR (case-control study of mortality risk factors in SJS/TEN patients) found that neither corticosteroids, nor IVIG showed any significant effect on mortality, compared to supportive care alone.40 Studies have shown that IVIG arrests Fas-mediated keratinolysis in vitro,41 which provides a pathophysiologic explanation of why it has been shown to be beneficial, with rapid cessation of skin lesions and decreased mortality, in several small case series.42 However, other studies have found a higher mortality and a longer hospitalization,43 or no benefit in outcomes with IVIG.40

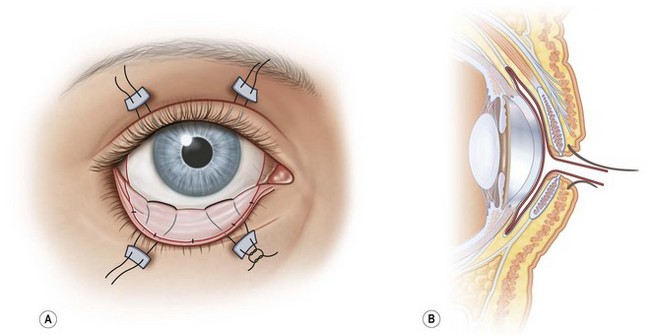

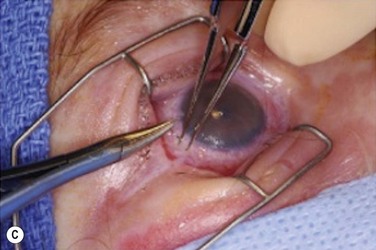

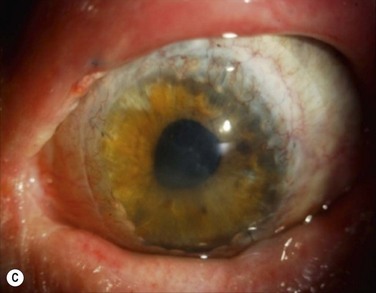

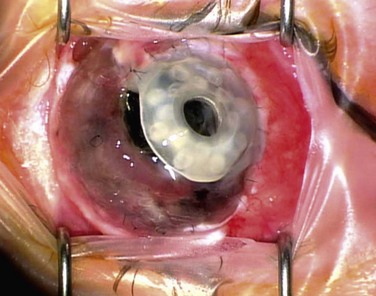

Ocular – Acute

There have been several case series reporting success with the use amniotic membrane (AMT) during the acute phase of SJS/TEN.44–46 AMT is the innermost layer of the placental membrane, consisting of a thick basement membrane and an avascular stroma. It exerts anti-inflammatory and antiscarring actions and is used to facilitate wound healing, including persistent corneal epithelial defects, acute chemical or thermal burns, or recurrent pterygiums.46 In SJS/TEN, cryopreserved AMT is sutured to cover the entire ocular surface from lid margin to lid margin as a temporary biological bandage as shown in Figure 30.3.45,47 The eyelashes are trimmed, and the edge of the piece of AMT is sutured to the external eyelid skin 1–2 mm from the lash line using an 8-0 nylon running suture.44–46 The AMT is oriented stromal surface in contact with conjunctiva. It is spread to cover tarsal conjunctiva and fornix, then reflected to cover bulbar conjunctiva using muscle hooks. The AMT is anchored to skin using double-armed 6-0 prolene sutures passed through the eyelids and secured over the skin with a bolster. The AMT is fixed to the episclera with a continuous 10-0 nylon suture near the limbus. Either a symblepharon ring or Kontour bandage contact lens is used to separate eyelid from eyeball. Prokera™, a symblepharon ring with a sheet of AMT clipped to it, has also been used but has been found to provide inadequate coverage of the forniceal and palpebral conjunctiva and lid margins.44,45 If Prokera™ is used, it is recommended that one must also use separate AMT to cover the eyelid margin and palpebral conjunctiva. Gregory44 reported successfully treating 10 patients with AMT, with all patients having epithelial sloughing involving large areas of the ocular surface. They were treated within 10 days of onset of symptoms, and the AMT repeated every 10 to 14 days if inflammation and sloughing persisted. Dry eye severity and ocular surface and eyelid scarring was mild to moderate in all patients.

Ocular – Chronic

The goals of treatment in the chronic stages of EM/SJS/TEN are:

Management of Dry Eye

The extent of compromise of tear function preoperatively is inversely correlated with the success rate of ocular surface reconstruction procedures.48 Frequent non-preserved artificial tears should be used to treat the keratoconjunctivitis sicca that results from loss of goblet cells and scarring of the lacrimal ductules. Autologous serum eye drops (ASE) have been recommended as a useful alternative treatment in severe dry eye.49 Topical transretinoic acid is commercially available and been shown to improve clinical features of dry eye in correlation with the degree of squamous metaplasia in patients with severe dry eye disorders.50 Chronic conjunctival inflammation will perpetuate the dry eye state and should be managed with topical steroids and cyclosporine. Punctal occlusion to retain the tear film, and medial or lateral tarsorrhaphies to prevent exposure of the tear film to evaporation may also be helpful. The severe dry eye state can result in persistent corneal epithelial defects, and cause the patient to be in a constant state of photophobia and irritation. This may be improved with long-term bandage contact lenses. One study of 39 patients (67 eyes) fitted with scleral lenses for SJS/TEN found a significant improvement in visual acuity and ocular surface symptoms.51 Similarly, PROSE (prosthetic replacement of the ocular ecosystem) scleral lenses may be used to manage chronic ocular surface disease.

Management of Lid Disease

Abnormal eyelid anatomy may perpetuate corneal complications30 and should be addressed prior to any ocular surface reconstructive procedure. Trichiasis is a recurrent problem in these patients and may be managed by various techniques, including epilation, electrolysis, argon laser treatment, and cryotherapy. Symblepharon and fornix foreshortening may be addressed by symblepharolysis and conjunctival recession, with the placement of mucous membrane grafts, such as hard palate, nasal or buccal mucosa, or amniotic membrane. Symblepharon may also be addressed at the time of keratolimbal allograft. Cicatricial entropion or ectropion may be corrected by a variety of surgical methods, including placement of a skin or mucous membrane graft.

Ocular Surface Reconstruction

EM/SJS/TEN patients with LSCD have the worst prognosis for ocular surface reconstruction surgery, due to chronic ocular surface inflammation (stage c ocular surface disease),52 extremely dry eye, and other cicatricial complications. It is important to manage the ocular inflammation preoperatively and to wait until the inflammation is minimized before proceeding with surgery. If surgery is performed during active inflammation, there is an increased risk of delayed epithelial healing, corneal melts, and immune rejection postoperatively. A lateral and/or medial tarsorrhaphy should be strongly considered at the time of ocular surface reconstruction surgery.

EM/SJS/TEN is a bilateral disease, so a conjunctival limbal autograft from the fellow eye is not an option. The two remaining options are ocular surface stem cell transplantation (OSST) from an allograft donor with or without an optical keratoplasty, or keratoprosthesis (KPro) surgery with either a Boston KPro or osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP). We do not advocate Boston Type 1 KPro surgery as the primary ocular surface reconstructive procedure in these patients, and the prognosis for Boston Type 1 KPro surgery in EM/SJS/TEN patients is worse than for other disorders.53 Due to the severe dry eye there is a high risk of corneal melting, infectious keratitis, endophthalmitis, and KPro extrusion. Figure 30.4 shows fungal keratitis and Figure 30.5 shows KPro extrusion in a patient with SJS who had undergone Boston type 1 KPro surgery.

Figure 30.5 SJS patient (same eye as in Figure 30.2) with KPro extrusion.

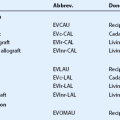

Allograft transplantation can be from a cadaver-donor keratolimbal allograft (KLAL) or living-related conjunctival limbal allograft (lr-CLAL), or a combination of both lr-CLAL/KLAL (the Cincinnati procedure).54 A further option is transplantation of ex vivo cultured stem cells. Systemic immunosuppression is required in allograft transplantation to prevent immune rejection of the richly vascularized and antigenic limbal stem cells. SJS-related ocular surface disease carries a worse prognosis compared to other indications for these procedures, such as aniridia or contact lens-induced keratitis.55–57 Aside from the chronic inflammation and cicatricial eyelid pathology, one of the major reasons for ocular surface failure is the severe dry eye and mucin deficiency seen in these patients. It has been suggested that combining lr-CLAL and KLAL is beneficial in replacing not only deficient limbal stem cells, but also conjunctival goblet cells.54 Figure 30.6 shows the preoperative photographs of severe ocular surface failure in a patient with SJS, and the postoperative appearance after combined lr-CLAL/KLAL and penetrating keratoplasty.

In eyes with severe keratinization an osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP)58 or a Boston type 2 keratoprosthesis59 may be more suitable. However, these procedures are highly complex and performed only in a few centers around the world.

References

1. Hebra, F. On diseases of the skin, including the exanthemata. Translated and edited by CH Fagge. London: New Sydenham Society; 1866.

2. Stevens, AM, Johnson, FC. A new eruptive fever associated with stomatitis and ophthalmia: report of two cases in children. Am J Dis Child. 1922;24:526–533.

3. Thomas, BA. The so-called Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Br Med J. 1950;1:1393–1397.

4. Lyell, A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: an eruption resembling scalding of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1956;68:355–361.

5. Bastuji-Garin, S, Rzany, B, Stern, RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92–96.

6. Chan, HL, Stern, RS, Arndt, KA, et al. The incidence of erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. A population-based study with particular reference to reactions caused by drugs among outpatients. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:43–47.

7. Assier, H, Bastuji-Garin, S, Revuz, J, et al. Erythema multiforme with mucous membrane involvement and Stevens–Johnson syndrome are clinical different disorders with distinct causes. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:539–543.

8. Rzany, B, Mockenhaupt, M, Baur, S, et al. Epidemiology of erythema exudativum multiforme majus, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Germany (1990–1992): structure and results of a population-based registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:769–773.

9. Schöpf, E, Stühmer, A, Rzany, B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. An epidemiologic study from West Germany. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:839–842.

10. Roujeau, JC, Guillaume, JC, Fabre, JP, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome). Incidence and drug etiology in France, 1981–1985. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:37–42.

11. Auquier-Dunant, A, Mockenhaupt, M, Naldi, L, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Correlations between clinical patterns and causes of erythema multiforme majus, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: results of an international prospective study. SCAR Study Group. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1019–1024.

12. Hazin, R, Ibrahimi, OA, Hazin, MI, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med. 2008;40:129–138.

13. Chang, YS, Huang, FC, Tseng, SH, et al. Erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acute ocular manifestations, causes, and management. Cornea. 2007;26:123–129.

14. Roujeau, JC, Kelly, JP, Naldi, L, et al. Medication use and the risk of Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1600–1607.

15. Paul, C, Wolkenstein, P, Adle, H, et al. Apoptosis as a mechanism of keratinocyte death in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:710–714.

16. French, LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: our current understanding. Allergol Int. 2006;55:9–16.

17. Abe, R, Shimizu, T, Shibaki, A, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome are induced by soluble Fas ligand. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1515–1520.

18. Inachi, S, Mizutani, H, Shimizu, M. Epidermal apoptotic cell death in erythema multiforme and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Contribution of perforin-positive cell infiltration. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:845–849.

19. Chung, WH, Hung, SI, Yang, JY, et al. Granulysin is a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nat Med. 2008;14:1343–13450.

20. Power, WJ, Ghoraishi, M, Merayo-Lloves, J, et al. Analysis of the acute ophthalmic manifestations of the erythema multiforme/Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis disease spectrum. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1669–1672.

21. Chung, WH, Hung, SI, Hong, HS, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Nature. 2004:428–486.

22. Hung, SI, Chung WH Liou, LB, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4134–4139.

23. Paquet, P, Pierard, GE. Erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a comparative study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:127–132.

24. Rzany, B, Hering, O, Mockenhaupt, M, et al. Histopathological and epidemiological characteristics of patients with erythema exudativum multiforme major, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermato. 1996;135:6–11.

25. Guegan, S, Bastuji-Garin, S, Poszepczynska-Guigne, E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272–276.

26. Bastuji-Garin, S, Fouchard, N, Bertocchi, M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149–153.

27. Arstikais, MJ. Ocular aftermath of Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;90:376–379.

28. Tauber, J. Autoimmune diseases affecting the ocular surface. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, eds. Ocular surface disease: medical and surgical management. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

29. De Rojas, MV, Dart, JK, Saw, VP. The natural history of Stevens–Johnson syndrome: patterns of chronic ocular disease and the role of systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1048–1053.

30. Di Pascuale, MA, Espana, EM, Liu, DT, et al. Correlation of corneal complications with eyelid cicatricial pathologies in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:904–912.

31. Tatnall, FM, Schofield, JK, Leigh, IM. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of continuous acyclovir therapy in recurrent erythema multiforme. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:267–270.

32. Foster, CS, Fong, LP, Azar, D, et al. Episodic conjunctival inflammation after Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:453–462.

33. Garcia-Doval, I, LeCleach, L, Bocquet, H, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:323–327.

34. Kelemen, JJ, Cioffi, WG, McManus, WF, et al. Burns center care for patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:273–278.

35. Palmiere, TL, Greenhalgh, DG, Saffle, JR, et al. A multicenter review of toxic epidermal necrolysis treated in U.S. burn centers at the end of the twentieth century. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:87–96.

36. Gerull, R, Nelle, M, Schaible, T. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome; a review. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1521–1532.

37. Dalli, RL, Kumar, R, Kennedy, P, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis/Stevens–Johnson syndrome: current trends in management. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:671–676.

38. Halebian, PH, Corder, VJ, Madden, MR, et al. Improved burn center survival of patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis managed without corticosteroids. Ann Surg. 1986;204:503–512.

39. Rasmussen, JE. Erythema multiforme in children. Response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:181–186.

40. Schneck, J, Fagot, FP, Sekula, P, et al. Effects of treatments on the mortality of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective study on patients included in the prospective EuroSCAR study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:33–40.

41. Viard, I, Wehrli, P, Bullani, R, et al. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science. 1998;282:490–493.

42. Prins, C, Kerdel, FA, Padilla, RS, et al. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins: a multicenter retrospective analysis of 48 consecutive cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:26–32.

43. Brown, KM, Silver, GM, Halerz, M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: does immunoglobulin make a difference? J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:81–88.

44. Gregory, DG. Treatment of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:908–914.

45. Shammas, MC, Lai, EC, Sarkar, JS, et al. Management of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis utilizing amniotic membrane and topical corticosteroids. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:202–213.

46. Shay, ES, Kheirkhah, A, Liang, L, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation as a new therapy for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Surv Ophthal. 2009;54:686–696.

47. Meller, D, Pires, RT, Mack, RJ, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for acute chemical or thermal burns. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:980–989.

48. Shimazaki, J, Shimmura, S, Fujishima, H, et al. Association of preoperative tear function with surgical outcome in severe Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1518–1523.

49. Management and Therapy Subcommittee members of the International Dry Eye Work Shop. Management and therapy of dry eye disease: Report of the Management and Therapy Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Work Shop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5:163–178.

50. Tseng, SCG. Topical tretinoin treatment for severe dry-eye disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 Pt 2):860–866.

51. Tougeron-Brousseau, B, Delcampe, A, Gueudry, J, et al. Vision-related function after scleral lens fitting in ocular complications of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:852–859.

52. Schwartz, GS, Gomes, JAP, Holland, EJ. Preoperative staging of disease severity. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, eds. Ocular surface disease: medical and surgical management. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

53. Yaghouti, F, Nouri, M, Abad, JC, et al. Keratoprosthesis: preoperative prognostic categories. Cornea. 2001;20:19–23.

54. Biber, JM, Skeens, HM, Neff, KD, et al. The Cincinnati procedure: technique and outcomes of combined living-related conjunctival limbal allografts and keratolimbal allografts in severe ocular surface failure. Cornea. 2011;30:765–771.

55. Solomon, A, Ellis, P, Anderson, DF, et al. Long-term outcome of keratolimbal allograft with or without penetrating keratoplasty for total limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1159–1166.

56. Samson, CM, Nduaguba, C, Baltatzis, S, et al. Limbal stem cell transplantation in chronic inflammatory eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:862–868.

57. Shimazaki, J, Higa, K, Morito, F, et al. Factors influencing outcomes in cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation for chronic cicatricial ocular surface disorders. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:945–953.

58. Liu, C, Okera, S, Tandon, R, et al. Visual rehabilitation in end-stage inflammatory ocular surface disease with the osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis: results from the UK. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1211–1217.

59. Pujari, S, Siddique, SS, Dohlman, CH, et al. The Boston keratoprosthesis type II: the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary experience. Cornea. 2011;30:1298–1303.