Chapter 89 Epilobium Species (Fireweed)

Epilobium spp. (family: Onagraceae)

General Description

General Description

Epilobium is a genus of some 200 species that typically grow at relatively high latitudes or high altitudes.1 This perennial is found in all parts of the world. It has tall, erect, and somewhat woody stems, from 2 to 7 ft tall, crowded with long, narrow, alternate leaves that are from 2 to 6 in long. Its flowers range from lavender to pink to carmine-purple, and its pods are long, narrow, and filled with feathery seeds.2 Most species have small flowers (e.g., Epilobium parviflorum, known as small-flowered willow herb). A few have large flowers (e.g., E. angustifolium, known as great willow herb). Despite the use of the term “willow,” there is no relationship between Epilobium spp. and Salix spp. (willow).

Chemical Composition

Chemical Composition

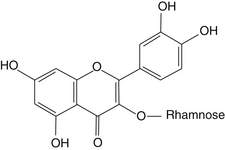

The aerial parts are rich in flavonoids3 and flavonol glycosides based on kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin skeletons.4 The plants contain complex tannins such as ellagitannins (oenothein A and B) and gallotannins5; β-sitosterol; triterpenes6; and gallic, chlorogenic, and ellagic acids.7 In the small-flowered species, myricetin is the predominant flavonoid. The large-flowered species have a completely different flavonoid pattern, with isoquercitrin being predominant. The plant contains the highest content of the flavonoid myricetin 3-0-β-D-glucuronide shortly after flowering (Figure 89-1).

History and Folk Use

History and Folk Use

Fireweed has been widely used as a medicine and as a food in many parts of the world. Native Americans used it for burning urination, male urination problems, coughs and sore throats, stomachaches and intestinal discomfort, bowel hemorrhages, gastritis, tuberculosis, and as a panacea for pain.8 It was used as a poultice for boils; abscesses; carbuncles; bruises; infected sores, cuts, and wounds; and other skin ailments. Various Eskimo and Siberian tribes also used the plant to treat sores.9 Young shoots were widely consumed as food and fodder, as were the roots and leaves. The seed fluff was used for weaving cloth, making thread, and starting fires. Fireweed is named mjoelke in Scandinavia, a derivation of the word milk, because of centuries of observation that cows grazing on the plant produce more milk.

Eclectic physicians considered fireweed unequaled as a treatment for summer bowel troubles and also used it in other types of diarrhea, including cholera infantum and typhoid dysentery.10 The Eclectics often administered fireweed as an infusion, using frequent small doses (up to every 10 minutes). E. hirsutum was used in Egyptian and European folk medicine to treat inflammation, adenoma, and prostate tumors.11 Europeans also used the plant to treat eczema, seborrhea, other skin conditions, and menstrual disorders.12 The plant was also used for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia.13

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Analgesic Effect

Ethanolic extracts of E. angustifolium injected subcutaneously had a weak analgesic effect on mice in the hot plate test, whereas its analgesic effect was greater than that of acetylsalicylate in the acetic acid test.14 In mice, an extract of E. hirsutum had an analgesic effect comparable to morphine and diclofenac.15

Antidiarrheal Effect

Fireweed showed significant antidiarrheal and antimotility effects in a variety of animal models.16

Antiinflammatory Effect

Aqueous extracts of E. angustifolium (40 mg/kg orally) strongly reduced the release of prostaglandins and depressed edema in vivo.17 Its effect on edema was equivalent to indomethacin (2 mg/kg). E. parviflorum did not suppress edema and had about 20% of the effect on prostaglandin release. Isolated myricetin-3-0-β-D-glucuronide was 10 times more effective than indomethacin at inhibiting edema in rats, was equally effective at inhibiting prostaglandin biosynthesis, and had a dose-related antiarthritic effect.18,19 It inhibited both cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 nearly equivalently and inhibited 5-lipooxygenase comparably to nordihydroguaiaretic acid. It dose-dependently inhibited platelet aggregation equivalently to indomethacin, but in contrast to indomethacin, induced no gastric ulcers. The compound may be safer than nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, since it prevents the arachidonic shunting that results in the formation of leukotrienes.

Antimicrobial Effect

Dilute extracts of fireweed are antimicrobial in vitro.20 E. angustifolium and E. rosmarinifolium have the broadest spectrum of action, inhibiting bacteria, yeast, and fungi. E. angustifolium and E. hirsutum inhibited Microsporum canis at concentrations as low as 10 mcg/mL. In another study, E. angustifolium failed to inhibit Aspergillus niger but somewhat inhibited Candida albicans while strongly inhibiting Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.21

Antitumor Effect

Oenothein B, isolated from fireweed, showed some antitumor activity against sarcoma 180 in mice and some selectivity against lung cancer cells and two colon cancer lines, but did not have a noticeable effect on the prostate cancer lines tested.22 In other studies, E. angustifolium had a specific and significant antiproliferative effect on human prostate epithelial cells.23 In addition, several of its flavonoids were potent growth inhibitors when tested on various hormone-sensitive and hormone-nonsensitive cell lines.

Effect on Prostate and Prostatic Enzymes

Extracts of various fireweed species inhibited aromatase in vitro.24 This action was primarily attributed to oenothein A and B, but other fireweed flavonoids also inhibited aromatase. Both oenothein A and B had a considerably greater inhibitory action on 5-α-reductase in vitro than the reference drug finasteride. The aqueous extract and ultrafiltrate of E. angustifolium had an antiandrogenic effect in intact rats, and the aqueous extract had a proandrogenic effect in castrated rats.25 In another study, alcoholic extracts of fireweed failed to inhibit 5-α-reductase, whereas the aqueous extract showed significant inhibition.26 This action was attributed to the compound oenothein B.

Dosage

Dosage

Dosages for fireweed are not well established. Fireweed is traditionally administered as a standard infusion using 2 to 3 teaspoons of herb to 1 cup of boiling water, taken as needed.27 The suggested dose for an aqueous/alcoholic tincture is 2 to 6 mL three times a day.

Aqueous/alcoholic tinctures appear to be more effective than tinctures with a high alcohol concentration.28,29 No widely accepted standardization exists to ensure quality fireweed extracts, although flavonoid profiles can be used to distinguish the various species.30,31 Species grown in Africa appear to have a significantly higher content of oenothein B than the same species grown in Europe.32

Toxicology

Toxicology

Fireweed has no known toxic effects, and its lack of toxicity is underscored by a worldwide use as both food and fodder. The median lethal dose for injected ethanol extract in mice is 1.4 g/kg.33

1. Averett J.E., Kerr B.J., Raven P.H. The flavonoids of Onagraceae, tribe Epilobieae: Epilobium sect. Epilobium. Am J Bot. 1978;65:567–570.

2. Moore M. Medicinal plants of the Pacific West. Santa Fe, NM: Red Crane Books; 1995. 136-138

3. Ducrey B., Marston A., Gohring S., et al. Inhibition of 5 alpha-reductase and aromatase by the ellagitannins oenothein A and oenothein B from Epilobium species. Planta Med. 1997;63:111–114.

4. Averett J.E., Kerr B.J., Raven P.H. The flavonoids of Onagraceae, tribe Epilobieae: Epilobium sect. Epilobium. Am J Bot. 1978;65:567–570.

5. Ducrey B., Marston A., Gohring S., et al. Inhibition of 5 alpha-reductase and aromatase by the ellagitannins oenothein A and oenothein B from Epilobium species. Planta Med. 1997;63:111–114.

6. Glowniak K., Zareba S., Kozyra M., et al. P23 sterols and triterpenoids from Epilobium sp. and some other medicinal plants (poster). Eur J Pharm Sci. 1994;2:124.

7. Lesuisse D., Berjonneau J., Ciot C., et al. Determination of oenothein B as the active 5-alpha-reductase-inhibiting principle of the folk medicine Epilobium parviflorum. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:490–492.

8. Moerman D.E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press; 1998. 212-213

9. Kallman S. [Wild Plants as Food & Medicine.]. Vasteras, Sweden: ICA Bokforlag; 1997. 152-155: [Swedish]

10. Felter H.W., Lloyd J.U. King’s American Dispensatory, Vol. 1. Sandy OR: Eclectic Medical Publications. 1993. 711-712

11. Barakat H.H., Hussein S.A.M., Marzouk M.S., et al. Polyphenolic metabolites of Epilobium hirsutum. Phytochem. 1997;46:935–941.

12. Battinelli L., Tita B., Evandri M.G., et al. Antimicrobial activity of Epilobium spp. extracts. Farmaco. 2001;56:345–348.

13. Hevesi B.T., Houghton P.J., Habtemariam S., et al. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory effect of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Phytother Res. 2009;23:719–724.

14. Tita B., Abdel-Haq H., Vitalone A., et al. Analgesic properties of Epilobium angustifolium, evaluated by the hot plate test and the writhing test. Farmaco. 2001;56:341–343.

15. Pourmorad F., Ebrahimzadeh M.A., Mahmoudi M., et al. Antinociceptive effect of methanolic extract of Epilobium hirsutum. Pakistan J Biol Sci. 2007;10:2764–2767.

16. Vitali F., Fonte G., Saija A., et al. Inhibition of intestinl motility and secretion by extracts of Epilobium spp. in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:342–348.

17. Hiermann A., Juan H., Sametz W. Influence of Epilobium extracts on prostaglandin biosynthesis and carrageenin induced oedema of the rat paw. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17:161–169.

18. Hiermann A., Schramm H.W., Laufer S. Anti-inflammatory activity of myricetin-3-0-beta-D-glucuronide and related compounds. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:421–427.

19. Hiermann A., Reidlinger M., Juan H., et al. [Isolation of the antiphlogistic principle from Epilobium angustifolium.]. Planta Med. 1991;57:357–360. [German]

20. Battinelli L., Tita B., Evandri M.G., et al. Antimicrobial activity of Epilobium spp. extracts. Farmaco. 2001;56:345–348.

21. Rauha J.P., Remes S., Heinonen M., et al. Antimicrobial effects of Finnish plant extracts containing flavonoids and other phenolic compounds. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;56:3–12.

22. Ducrey B., Marston A., Gohring S., et al. Inhibition of 5 alpha-reductase and aromatase by the ellagitannins oenothein A and oenothein B from Epilobium species. Planta Med. 1997;63:111–114.

23. Vitalone A., Bordi F., Baldazzi C., et al. Anti-proliferative effect on a prostatic epithelial cell line (PZ-HPV-7) by Epilobium angustifolium L. Farmaco. 2001;56:483–489.

24. Ducrey B., Marston A., Gohring S., et al. Inhibition of 5 alpha-reductase and aromatase by the ellagitannins oenothein A and oenothein B from Epilobium species. Planta Med. 1997;63:111–114.

25. Hiermann A., Bucar F. Studies of Epilobium angustifolium extracts on the growth of accessory sexual organs in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55:179–183.

26. Lesuisse D., Berjonneau J., Ciot C., et al. Determination of oenothein B as the active 5-alpha-reductase inhibiting principle of the folk medicine Epilobium parviflorum. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:490–492.

27. Moore M. Medicinal plants of the Pacific West. Santa Fe, NM: Red Crane Books; 1995. 136-138

28. Hiermann A., Bucar F. Studies of Epilobium angustifolium extracts on the growth of accessory sexual organs in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55:179–183.

29. Lesuisse D., Berjonneau J., Ciot C., et al. Determination of oenothein B as the active 5-alpha-reductase inhibiting principle of the folk medicine Epilobium parviflorum. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:490–492.

30. Slacanin I., Marston A., Hostettmann K., et al. Isolation and determination of flavonol glycosides from Epilobium species. J Chromatol. 1991;557:391–398.

31. Averett J.E., Kerr B.J., Raven P.H. The flavonoids of onagraceae, tribe Epilobieae: Epilobium sect. Epilobium. Am J Bot. 1978;65:567–570.

32. Ducrey B., Marston A., Gohring S., et al. Inhibition of 5 alpha-reductase and aromatase by the ellagitannins oenothein A and oenothein B from Epilobium species. Planta Med. 1997;63:111–114.

33. Tita B., Abdel-Haq H., Vitalone A., et al. Analgesic properties of Epilobium angustifolium, evaluated by the hot plate test and the writhing test. Farmaco. 2001;56:341–343.