Epilepsy II

Treatment and management

Principles of medical treatment

Some refractory cases, on re-evaluation, prove to have non-epileptic (psychogenic) seizures, also referred to as pseudoseizures (p. 116). In others, poor compliance contributes to poor control.

Choice of medication

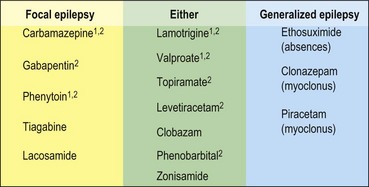

The major divisions into generalized and focal-onset epilepsies are important in the choice of drug (Fig. 1). Medications can broadly be divided into those useful in focal epilepsy, those with a broad spectrum of action and those for specific seizure types. Carbamazepine, lamotrigine and valproate are the commonest first-line drugs in the UK. The choice is also heavily influenced by the age of the patient because this affects their susceptibility to the side effects of different drugs. For example, focal-onset epilepsy in a young woman is often treated with carbamazepine or lamotrigine as first line because of its lower risk of teratogenicity, but sodium valproate is favoured in the elderly because of a lower risk of ataxia and falls. Lamotrigine is emerging as a broad-spectrum drug, well tolerated in many patient groups.

Adverse effects

The adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs are common and major adverse effects are listed in Table 1. Sedation can occur with all drugs and is the most common complaint, especially with polytherapy. Another concern is teratogenicity. Women of childbearing age on antiepileptic medication should be counselled of the risk and their medication minimized prior to conception. Although not proven to be of benefit, folic acid supplements (5 mg daily) are generally prescribed to women of childbearing age taking antiepileptic drugs as it may help to prevent neural tube defects. The risk of major malformations for a woman taking anticonvulsants is about 4–9%, compared with about 1–2% in the general population. It is highest for those on valproate and on multiple drugs.

| Adverse effect | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Sedation |

When to stop treatment

In general, the same factors that predict seizure recurrence are also associated with relapse on cessation of treatment. If medication is withdrawn after 2 years of being seizure-free, there is a risk of recurrence of 25–40%. There is no absolute predictive test, and seizure recurrence is always less if patients continue with treatment than if they stop. For this reason, the decision to stop treatment is largely a personal one. For example, a woman who wants to start a family may accept a recurrence of partial seizures if it means that her baby is not exposed to the teratogenic effects of drugs in utero, but a travelling salesman may wish to continue with medication indefinitely, rather than increase the risk of losing his driving licence.

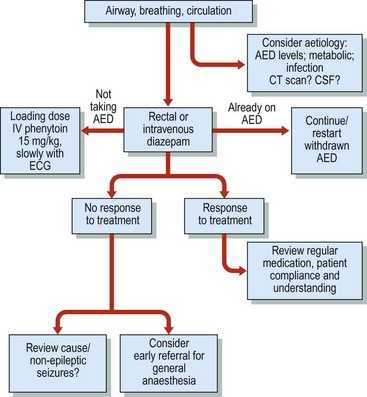

Management of status epilepticus

Patients fall into two general categories: those with a previous diagnosis of epilepsy and those presenting for the first time, in whom serious new disease underlying the seizures is likely (Fig. 2). The cause may be metabolic dysfunction, drugs, intracranial mass lesions, haemorrhage or infection. These patients need to be investigated for metabolic disturbance, undergo urgent neuroimaging and, if this is normal, CSF analysis, especially to look for encephalitis. An EEG may also help with this diagnosis.