Epilepsy I

Diagnosis

A seizure is a paroxysmal neurological event caused by the abnormal discharge of neurones. Epilepsy is defined as a tendency to recurrent seizures, that is two or more seizures. Epilepsy is not a single disease but it is a symptom of congenital or acquired CNS disease in the same way as weakness is a symptom in a range of different disorders. Different types of epilepsy can be classified according to different features, including seizure type, age of onset, prognosis and cause, and are more appropriately called the epilepsies.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of epilepsy is clinical, depending on the history from the patient and, critically, from any witnesses of the attacks. This can be supported by investigations such as an EEG, but the main contribution of the EEG is in syndrome classification. The differential diagnosis of blackouts is discussed on page 44.

Classification of seizures and epilepsy syndromes

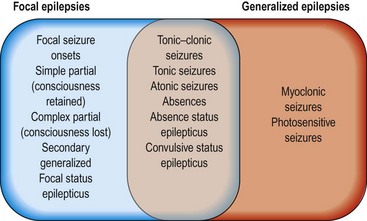

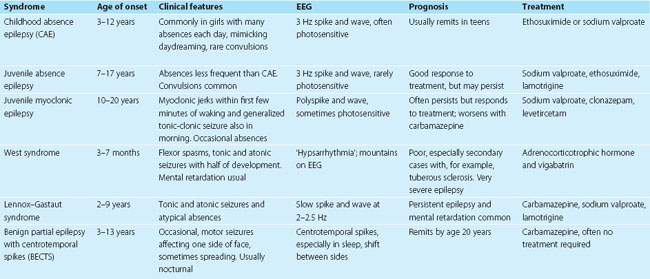

Much of the confusion about the classifications in epilepsy arise because of a failure to appreciate that there are two interrelated classifications: a classification of seizure type (Fig. 1) and a classification of epilepsy syndromes (Table 1). Patients may have more than one type of seizure. The epilepsy syndrome includes diagnosis of seizure type and additional information, mostly relating to aetiology, including age, EEG and neuroimaging results. Where possible, patients’ epilepsy should be classified by epilepsy syndrome rather than seizure type, which takes into account these other factors. The old terms ‘petit mal’ and ‘grand mal’ do not fit easily into this classification and should not be used.

There are three broad categories of epilepsy syndromes:

Patients who have had only a few attacks may not be classifiable into an epileptic syndrome.

Generalized epilepsies

These usually start in childhood or adolescence and have typical clusters of seizure types, including tonic-clonic seizures, absences and myoclonic jerks, combined with a characteristic generalized EEG ‘signature’. The most common forms are the idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGEs), which represent well-defined clinical syndromes (Table 2) and are not associated with structural brain disease. They generally have a good prognosis. There is a constitutional component with a significantly increased risk of epilepsy among family members.

| Seizure symptom | Clinical significance |

|---|---|

| FocalFocal limb jerkingFocal tinglingOlfactory or gustatory hallucinationVisual hallucinationLimb posturingSwallowing/chewing movements | Motor cortex onsetSomatosensory cortex onsetTemporal lobe onsetOccipital lobe onsetSupplementary motor area onsetTemporal lobe/insula |

Focal epilepsy

Focal epilepsy occurs at any age. The abnormal discharge appears to start in one part of the brain and may become generalized. The focal onset may be reflected in focal symptoms at the onset of the seizure, indicating the abnormal region of cortex (Table 2). The spread may be so rapid that the seizure appears to be a generalized convulsion from the outset and there are no early focal symptoms. There may be a post-ictal confusional state, during which the patient may wander and undertake stereotyped actions that appear purposeful (‘automatisms’). These may include plucking at objects, or sometimes more sophisticated behaviours such as bed making or undressing. Without an EEG during the episode, this can be difficult to differentiate from complex partial status epilepticus (see below). An inter-ictal EEG (between seizures) may show localized spikes or sharp waves. This helps to support the diagnosis but their location does not always accord with the region of seizure onset.

The benign focal epilepsies of childhood, for example BECTS (see Table 1), are relatively common focal epilepsies that usually remit in adolescence and are not associated with focal structural abnormalities.

Investigation

An EEG is required to characterize the epilepsy but may be normal and this does not exclude a diagnosis of epilepsy. Repeating the EEG, especially with sleep deprivation, increases the diagnostic yield (p. 32). In some cases, a prolonged, ambulatory EEG recording can ‘catch’ an attack, in which case it is helpful in diagnosis.