7 Epilepsy

Introduction

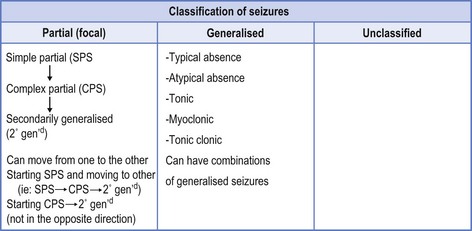

Extrapolating from this, epilepsy is not a satisfactory diagnosis. It represents a symptom of another underlying diagnosis that has provoked the seizures. This has translated into an internationally accepted classification of seizures (see Fig 7.1),1 which offers the road map to provide treatment options.

There is also an internationally accepted classification of the epilepsies2 (note the plural) provided to allow the clinician to acknowledge that one type of epilepsy may incorporate numerous seizure types (see Box 7.1).

Box 7.1 Some typical syndromes

The classification of the epilepsies also permits prediction of prognosis, thereby making both classifications part and parcel of a better understanding of the condition. An easier way to describe this is that the description of seizures offers phenomenology of the event, and description of the epilepsies provides a syndromal approach. As these classifications should mirror current knowledge, the leaders in the field are constantly trying to improve their content and suggesting enhanced pedagogy.3

Diagnosis of Epilepsy

A comprehensive history is the principal tool of all neurology. The patient often is unable to report exactly what happened during the seizure due to loss of consciousness, but the doctor should not capitulate at this point. The patient should be able to describe what they were doing just before the seizure and any preliminary symptoms, such as the perception of bad smell (e.g. burning rubber), bad taste (e.g. metallic taste), or a feeling that the unfamiliar is familiar (déjà vu—I have seen it before) or the opposite (jamais vu—the familiar is unfamiliar—I have not seen it before). The patient may be able to identify flashing lights as a photic stimulation that provoked the seizure, but this only occurs in approximately 10% of people with epilepsy.4 Stress, fatigue, sleep deprivation, drugs, alcohol or even sleep itself can provoke seizures. Menstruation and hormonal changes may cause seizures. Most of this information is readily available from the patient if the right questions are asked (see Table 7.1).

| Question | Answers pointing to epilepsy |

|---|---|

| When and where did the seizure occur? |

The patient will know if they bit their tongue, buccal mucosa or injured themselves in a seizure. Similarly, they can report if they were incontinent of urine or faeces. The patient will also know how they felt in the post-ictal period, whether they were confused, disoriented, exhausted and had to sleep, or if they had a headache. Thus the history from the patient is very helpful (see Table 7.1).

In addition, a history from any eyewitness will help the doctor to ascertain a word picture of what occurred during the seizure. Questions should include: did the patient appear absent; were there automatisms (automatic behaviour such as smacking lips, fiddling with clothing, involuntary behaviour or apparently purposeful activity for which the patient has no recall); did the patient turn the head to one or the other side; where, if identified, did the seizure start (such as in one hand or in the face to then move throughout the body); were the eyes open or shut (often used to differentiate non-epileptic, pseudo-seizures from truly epileptic phenomena where eyes are open); did the patient shake, twitch, talk, writhe, flail or do anything else during the episode? (See Table 7.2.)

TABLE 7.2 Description of seizures

| Seizure type | Description |

|---|---|

| Simple partial seizure (SPS) | Consciousness retained but focal features determined by site of seizure, such as perception of a smell, a sound or a vision. Uncontrolled movement or twitching of a part of the body, such as a thumb or hand, without loss of consciousness, which may spread (such as Jacksonian march in focal motor seizure). |

| Complex partial seizure (CPS) | Differentiated from SPS by altered state of consciousness. Patient may be unaware or poorly relate to the surrounding environment as with déjà vu (false memory) or jamais vu (blocked real memory). The patient, while non-responsive, may have automatisms—automatic behaviour that can be quite complex—such as driving a car. The appearance may be of a patient on automatic pilot. The patient has post-ictal features of fatigue, headache or confusion. ‘Absence’ with post-ictal features may be CPS rather than generalised absence. |

| Secondarily generalised seizure | This is a convulsive seizure that follows focal onset. A convulsion in which the patient reports an aura (representing a focal seizure) is experiencing secondary generalisation (2° gend) throughout the brain. |

| Typical absence | The patient has generalised absence that is short lived and often multiple, possibly provoked by hyperventilation. There is often no post-ictal feature. |

| Atypical absence | Similar to typical absence but may have automatisms. Differentiation from CPS may be difficult. EEG with typical 3 Hz spike and wave pattern may be necessary to differentiate from CPS, which will have more focal, often temporal lobe abnormality. |

| Tonic seizure | Drop attacks with hands and arms often coming up in front of the body and the head dropping forward as the patient becomes stiff and falls down, usually forward. |

| Myoclonic seizure | Sudden jerking of limbs and head—often first thing in the morning after waking. A form of generalised seizure without focal features. |

| Tonic clonic seizure | Primarily generalised convulsive seizure starting abruptly without focal features. Similar features to 2° gend but without focality—no aura at onset. |

After spending considerable effort to define the seizure the next step is to determine if there are precipitating factors, such as illness, genetic influences (with family history), or exposure to toxins. An obstetric history looking for birth trauma is important, as is any other history of brain damage from accidents, assaults or trauma. An educational history gives a clue regarding poor cognition and possible impaired function. A past history of febrile convulsions is worth seeking as is the detailed past medical and surgical history.

Investigation of the Patient with Epilepsy

a Electroencephalograph

One of the first tests is an electroencephalograph (EEG). It is imperative for the family doctor to appreciate that 10% of ‘normal’ patients can have an abnormal EEG and, at the same time, a person with epilepsy can have a normal EEG.5 If ten interictal EEGs are performed in a person with diagnosed epilepsy, 25% will all be abnormal, 60% will have at least one abnormal study and 15% will have all ten studies being normal. A typical epileptiform EEG is helpful when making the diagnosis, but a vaguely abnormal or completely normal EEG is neither helpful nor unhelpful.

If the first EEG is normal but the suspicion of epilepsy is high, then a repeat study with sleep deprivation may prove helpful. Where the diagnosis of epilepsy is suspicious and the question of non-epileptic seizure (pseudo-seizure) is raised, video EEG may clarify the situation and may be enhanced with sleep deprivation. Invasive EEG, relevant to more aggressive intervention, such as epilepsy surgery, will not be further discussed. Interpretation of EEG is the domain of the neurologist but it is helpful when requesting an EEG to state the reason for ordering it. Concurrent with the EEG there is usually a modified lead-2 electrocardiograph (ECG) rhythm strip. A normal EEG may still provide a diagnosis by identifying cardiac pathology, such as dysrhythmia, asystole or aberrant conduction (e.g. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome)6 which gives a possible reason for the episodes—such as cardiac-caused syncope.

b Cerebral imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is far superior to computer tomography (CT), and a normal CT may not exclude cerebral pathology. MRI is usually accompanied by MRA (angiography), which may reveal aberrant vessels or increased vascularity to an area of the brain. Gadolinium enhancement may reveal tumours or abscesses.

Differential Diagnosis

Epilepsy is itself not a stand-alone diagnosis. In many cases it is secondary to some other underlining condition, so the doctor must be acutely aware of alternative diagnoses (see Table 7.3).

| Syncope |

These may also exclude epilepsy altogether. The most common ‘mimic’ of a seizure is syncope. Syncope will be accompanied by negative ‘epilepsy’ tests, although it may reveal abnormal lead-2 rhythm ECG tracing during the EEG. Syncope will usually start abruptly, arrest spontaneously and be devoid of para-ictal features, such as confusion, fatigue or incontinence. There may be some epileptiform twitches due to cerebral hypoxia, which may create a diagnostic dilemma.7

Nocturnal parasomnias may mimic epilepsy. Somnambulism may be confused with ictal automatisms. Conversely, frontal lobe epilepsy, often with bizarre writhing and even mastibatory movements, particularly in female patients who are shown to rhythmically gyrate their pelvis in epilepsy telemetry, may be considered non-epileptic phenomena until the diagnosis is confirmed by the neurologist.8 Concurrent with this recognition that sleep-related phenomena may be confused with epilepsy, it is also important to respect that such phenomena may also provoke seizures due to sleep disturbance and possible additional hypoxaemia affecting the brain. Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) with twitching, jerking and gasping for air may be confused with epilepsy. OSA was first diagnosed as a consequence of epilepsy with overnight video monitoring. It should not be ignored that sleep is a neurological state and it is only with the advent of therapeutic interventions, such as continuous positive air pressure (CPAP), that respiratory physicians have claimed sleep medicine. Judicious use of CPAP, averting hypoxaemia and sleep deprivation in cases of OSA, has proven efficacious in seizure control, thereby recognising that epilepsy and OSA can co-exist, necessitating proper management of both.9

Transient global amnesia (TGA) in which the patient lacks recall of recent events may be confused with epilepsy.10 Even if the diagnosis of TGA is suspected, many clinicians will still investigate the patient for epilepsy.

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA),11 due to short-lived cerebral ischaemia, may be confused with epilepsy because of potentially short duration with possible post-ictal features and general good recovery. Acute index of suspicion is needed for such diagnoses.

Migraine is also within the differential and was discussed in an earlier review of headache (see Ch 6).

Briefly, anything that results in short-lived, altered cerebral function may resemble a seizure. Some events that are devoid of organicity, so called ‘non-epileptic seizures’ or ‘pseudo-seizures’, may resemble epilepsy. Some of the features have been discussed but the differentiation often requires involvement of a neurologist. Even the neurologist may be confused and misdiagnose non-epileptic seizures as the real thing. Two important features should be sought, namely, the potential gain for the patient and the source of the model for the featured behaviour. Even competent psychiatrists may have difficulty teasing these out, thereby making treatment difficult. One must remember that the same patient may demonstrate both real seizures and hence epilepsy, as well as non-epileptic phenomena, thus truly confounding the picture.12

Treating the Seizures

As already discussed, seizures are divided into those with focal or generalised onset. This differentiation determines the choice of optimal anti-epileptic medication (AEM). Carbamazepine (CBZ) [Tegretol®] is the choice for focal seizures, also known as partial seizures, and valproate (VPA) [Epilim®] is the choice for generalised seizures. These belong to the older generation of AEM, with both being first published in the 1960s. Phenytoin (PHT) [Dilantin®] is no longer a first-line agent because of saturable metabolism, which causes potential for a large increase in blood levels with minor dosage adjustment and a wide range of unwanted effects13 that can affect all bodily functions from pseudolymphoma to cardiac dysrhythmia and heart block. The reason for favouring the older AEMs is that none of the newer AEMs has surpassed them in head-to-head trials and they are far cheaper.14 There is evidence suggesting newer AEMs have a better side-effect profile15 but their cost precludes their initial use.14

It would be remiss not to mention generic AEMs. Many specialists argue against generics in epilepsy because one cannot be certain of absolute bio-equivalence. Allowing the pharmacist to switch from standard AEM to generics, recognising there may be more than one generic per AEM, could result in the patient continuously changing AEM, thus placing seizure control in jeopardy.16

If the patient does not respond to the initial AEM, be it CBZ or VPA, the likelihood of responding to subsequent AEM is less favourable.17 This does not exclude trying other AEM but this is probably the time to call in reinforcements (if the general practitioner initiated treatment without consultant input). Seizure control has become more complicated with respect to choosing AEM or combinations thereof. Competition between monotherapy (preferred) and rational polypharmacy, where certain combinations (such as VPA with lamotrigine (LTG)) have a mutually beneficial pharmacokinetic and pharmaco-dynamic interaction,18 is a hot topic.

AEM thought efficacious for generalised epilepsies include VPA, LTG, levetiracetam (LVT), topiramate (TPM) and maybe gabapentin (GBP) (see Table 7.4). These are ‘broad-spectrum’ AEM that can also be used for partial onset (focal) seizures.

| Generalised seizures | Partial seizures [focal] |

|---|---|

| Epilim® (valproate [VPA]) | Tegretol® (carbamazepine [CBZ]) |

| Lamictal® (lamotrigine [LTG]) | Epilim® (valproate [VPA]) |

| Keppra® (levetiracetam [LVT]) | Dilantin® (phenytoin [PHT]) |

| Topamax® (topiramate [TPM]) | Trileptil® (oxcarbazepine [OXC]) |

| Maybe Neurontin® (gabapentin [GBP]) | Lamictal® (lamotrigine [LTG]) |

Less broad spectrum AEM can usually only be used to treat focal seizures (see Table 7.4). They are either ineffective for generalised seizures or they may exacerbate some forms, such as CBZ exacerbating myoclonic seizures. Ethosuximide (Zarontin®) is an AEM only suitable for generalised absences but may exacerbate tonic–clonic seizures and largely has been replaced with VPA.

Other AEM within the newer generation available for focal seizures include oxcarbazepine (similar efficacy to CBZ with less central nervous system unwanted effects). Pregabalin, a new AEM developed after GBP, may have good efficacy although personal experience has not been encouraging (see Table 7.4). It is advisable to involve an epilepsy specialist if CBZ and VPA fail to achieve seizure control. Personal preference would advocate involvement of a neurologist to validate the diagnosis even before prescribing the first AEM, to choose the best AEM.

Prescribing Tegretol® or Epilim®

The above offered a broad overview of AEM treatment of seizures. What follows will focus specifically upon Epilim® (VPA) and Tegretol® (CBZ), acknowledging the use of trade rather than generic names. Ticking the appropriate box on the prescription that precludes brand substitution by the pharmacist obviates the risks of generic substitution. Unfortunately some pharmacists will substitute generics even if the box is ticked.

General practitioners recognise that patients are a law unto themselves: they do what is simple and rarely fully comply with the doctor’s advice. Thus it is imperative to provide options that accommodate the modern pace of living. The goal is to achieve seizure control with minimal disruption to quality of life, avoiding unwanted treatment effects, such as sedation. Before prescribing AEM, the doctor needs to warn the patient that unwanted effects may occur, to read the package insert and avoid dangerous situations, including driving.

Treating the Epilepsy

People have an established self-image, and adult or even adolescent onset epilepsy may threaten that image. Epilepsy invokes a lack of predictability—there is always the threat of another seizure without knowing exactly when, or even if, it will occur. The person who has had a first seizure has approximately 35–70% chance of a second seizure, and after a second seizure the risk is approximately 80% continuing to rise with each subsequent seizure.19,20

Seizures and driving are incompatible, such that the patient must be seizure free for predetermined periods of time to be permitted to drive. While the doctor advises the licensing authority on ‘fitness to drive’, the licensing authority is responsible for the final decision established within the Austroads Guidelines.21 This is not absolute and the doctor needs to acknowledge a duty of care both to the patient and the wider community. If a doctor does not stop a person with uncontrolled epilepsy from driving, there is potential for an injured third party to litigate against that doctor.

Psychosocial Issues

Teratogenicity needs to be considered, and folate may protect the neural axis during development. High doses of some AEM, such as VPA, are to be avoided if possible. Should pregnancy be planned then it is advisable, where possible, to wean out AEM prior to the pregnancy. It is generally too late to wean out medications after the pregnancy has been confirmed, as this is usually well into the first trimester. By this time potential teratogenicity, if it is to occur, will have happened and removal of AEM increases the risk of seizures.

1 Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981;22:489-501.

2 Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30:389-399.

3 Shinnar S. The new ILAE classification. Epilepsia. 2010;51(4):715-717.

4 Topalkara K, Alarcon G, Binnie CD. Effects of flash frequency and repetition of intermittent photic stimulation on photoparoxysmal responses. Seizure. 1998;7:249-255.

5 Smith SJ. EEG in the diagnosis, classification, and management of patients with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 2005;76(suppl. 2):ii2-ii7.

6 Pitney M, Beran RG, Jones A. The use of electroencephalography in the evaluation of loss of consciousness, and the importance of a simultaneous electrocardiogram. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;90:246-248.

7 Zaidi A, Fitzpatrick AP. Seizures and syncope: what’s the difference? Cardiac Electrophysiology Review. 2001;5:427-429.

8 Bazil CW, Malow BA, Sammaritano MR, editors. Sleep and epilepsy: the clinical spectrum. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2002.

9 Beran RG, Plunkett MJ, Holland GJ. Interface of epilepsy and sleep disorders. Seizure. 1999;8:97-102.

10 Shekhar R. Transient global amnesia: a review. International J. Clinical Practice. 2008;62(6):939-942.

11 Johnston SC. Transient ischemic attack. New England J Medicine. 2002;347(21):1687-1692.

12 Prueter C, Schultz-Venrath U, Rimpau W. Dissociative and associated psychopathological symptoms in patients with epilepsy, pseudoseizures and both seizure forms. Epilepsia. 2002;43(2):188-192.

13 Hart YM. Should first-line treatment of epilepsy differ for males and females? J Royal College Physicians (Edinburgh). 2003;33(suppl. 11):11-21.

14 Schmidt D. Drug treatment of epilepsy: are newer drugs more effective than older ones? In: Panayiotopoulos CP, editor. The atlas of epilepsies. Germany: Springer, Neu-Isenburg; 2010:1577-1582.

15 Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M, et al. The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalised and unclassifiable epilepsy: an unblinded, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1016-1026.

16 Chitty KM, Beran RG. Benefits and risks of generic substitution in epilepsy management. In: Panayiotopoulos CP, editor. The atlas of epilepsies. Germany: Springer, Neu-Isenburg; 2010:1583-1588.

17 Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Effectiveness of first antiepileptic drug. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1255-1260.

18 Pisani F, Oteri G, Russo MF, Di Perri R, Perucca E, Richens A. The efficacy of valproate-lamotrigine comedication in refractory complex partial seizures: evidence for a pharmacodynamic interaction. Epilepsia. 1999;40(8):1141-1146.

19 Hauser WA, Anderson VE, Loewenson RB, McRoberts SM. Seizure recurrence after a first unprovoked seizure. New England J Medicine. 1982;307(9):522-528.

20 Hall R. Prognosis after seizures. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2000;83:497.

21 Assessing fitness to drive: commercial and private vehicle drivers: medical standards for licensing and clinical management guidelines. Austroads & National Road Transport Commission, Sydney, 2001.