Chapter 15 Epilepsy

With contribution from Dr Lily Tomas

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder that is characterised by recurrent and unprovoked seizures. The lifetime risk of developing epilepsy is 3.2% with more than of 90% of these cases having partial or localisation-related epilepsy. Despite the introduction of newer anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs), nearly 50% of patients with partial epilepsy will not attain a seizure remission with the use of medication.1, 2, 3 In fact, a recent UK study indicated that although 30 000 people develop epilepsy annually, only 6000 have medically refractory seizures.1 Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs are a further major impediment to optimal dosing for seizure control.4 In the North American continent more than 3 million people have epilepsy.5

It is therefore easy to understand why at least 25–50% individuals with epilepsy have trialled some form of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy. Commonly used therapies include mind–body, dietary modification, nutritional and/or herbal supplementation, massage, homeopathy and acupuncture.6–9 It is important to note that many patients use CAM therapies without notifying their physician. Thus, it becomes the responsibility of the physician to actively inquire and then monitor therapies to ensure safety and effectiveness of combined CAM and traditional treatment.6, 10

In many instances, CAM therapies are not substitutes for traditional medications, however, depending on the effectiveness of the intervention(s), dosage reductions or cessation of medications under professional supervision may be possible.11

Lifestyle — general

Weight gain or loss is not an integral part of epilepsy although a sedentary lifestyle can contribute to weight gain. This is an important consideration because pharmacological treatment for epilepsy may be associated with substantial weight changes that may increase morbidity and impair adherence to the treatment regimen.12

Sleep

The close relationship between the physiological state of sleep and the pathological process underlying epileptic seizures has been known for centuries, however, it is still not well understood secondary to its complexity.13 Individuals with epilepsy demonstrate multiple sleep abnormalities including increased sleep latency, fragmented sleep, increased awakenings and stage shifts and an increase in stages 1 and 2 of non-REM sleep.14

Indeed, sleep is one of the best documented factors influencing the expression of seizures and interictal discharges. Many seizures are potently activated by sleep or arousal from sleep.14, 15 In fact, seizures occur during sleep in nearly one-third of patients. It has also been demonstrated that non-REM sleep components generally promote, and REM sleep components generally suppress, seizure discharge propagation.16, 17 Sleep deprivation can also increase the frequency of epileptiform discharges and seizures.18, 19, 20 The effective treatment of sleep disorders can improve seizure control. Indeed, AEDs, use of ketogenic dietary principles and vagus nerve stimulation can all improve sleep quality, daytime alertness and neurocognitive function.18

Poor sleep can also be an adverse effect of some AEDs. This should be identified and rectified where possible as sleep disturbance exerts greater effect than short-term seizure control on quality of life scores of patients with epilepsy.4, 21

Mind–body medicine

The historical relationship between the study of epilepsy and religious experience suggests particular potential associations between CAM therapies (especially spiritual healing and care for those with epilepsy).22 Traditional healers still use spiritual healing, often in combination with special magical concoctions, in order to exorcise evil spirits in their treatment of epilepsy.23, 24

Meditation practices

A recent systematic review of various meditative practices (meditation, meditative prayer, yoga, relaxation) has demonstrated strong evidence for the efficacy of meditation in the treatment of epilepsy.25 Clinical studies have shown that transcendental meditation (TM), derived from ancient yogic teachings, may be a potential anti-epileptic treatment. However, TM may possibly also be a double-edged sword as many of the EEG recordings during TM (increased alpha, theta, gamma frequencies with increased coherence and synchrony) are similar to seizure activity, with neuronal hypersynchrony being a cardinal feature of epilepsy. More rigorous trials are needed to determine this.26

Cognitive behaviour therapy

Overall, the current evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy remains contentious as reported by a recent Cochrane review.27 The review reports that 2 trials found CBT to be effective in reducing depression, among people with epilepsy with a depressed affect, whilst another did not. Two trials of CBT found improvement in quality of life scores. One trial of group cognitive therapy found no significant effect on seizure frequency while another trial found statistically significant reduction in seizure frequency as well as in seizure index (product of seizure frequency and seizure duration in seconds) among participants treated with CBT.27

Relaxation therapy and biofeedback

Two trials of combined relaxation and behaviour therapy and 1 of EEG biofeedback and 4 of educational interventions did not provide sufficient information to assess their effect on seizure frequency.27 One small study of galvanic skin response biofeedback reported significant reduction in seizure frequency. Combined use of relaxation and behaviour modification was found beneficial for anxiety and adjustment in 1 study. In 1 study EEG biofeedback was found to improve the cognitive and motor functions in individuals with greatest seizure reduction.27

Sunshine

The long-term treatment with various anticonvulsants may result in hypocalcaemia, osteomalacia and osteopaenia independent from Vitamin D metabolism. Regional variances in the incidences of drug-induced bone disease has been attributed to differences in sunlight exposure, with most reports from areas of little sunshine or from institutionalised patients.28, 29

Environment

Toxins

Toxic causes of seizures are numerous and include alcohol and other substances of abuse, drugs, and industrial and household products. Epileptic seizures have been induced by occupational nickel and other heavy metal exposure.30 There is also a reduction in the threshold for seizures in animals whose blood contents of lead are similar to those of humans from some urban areas with high levels of air pollution.31

Diurnal and seasonal variations

Research on hospital admissions with status epilepticus reveals an important association with several environmental protective and precipitating factors. There is a significant diurnal pattern, with most admissions between 4–5 p.m. and least admissions in early morning hours. Admissions also vary significantly across the lunar cycle, peaking at day 3 after the new moon and being minimal 3 days before new moon. Admissions are greatest on bright, sunny days whereas dark days, high humidity and high temperature appear to be significantly protective factors.32

Physical activity

Exercise

Many people with epilepsy, especially those with uncontrolled seizures, live a sedentary life and have poor physical fitness.33 Despite a shift in medical recommendations towards encouraging rather than restricting exercise, epileptics often fear they may suffer with exercise-induced seizures.34 Although there are rare cases of exercise induced seizures, clinical and experimental data has shown that physical activity can decrease seizure frequency, as well as lead to improved cardiovascular and psychological health in patients with epilepsy.35, 36, 37 Indeed, regular physical exercise may have a moderate seizure-preventative effect in 30–40% of this population.33

Animal studies are currently investigating whether physical activity is beneficial for preventing or treating chronic temporal lobe epilepsy.38

The majority of sports, including contact sports, are safe to participate in. Water sports and swimming are also considered to be safe if seizures are well controlled and supervision is present. Sports such as hang-gliding and scuba diving are not recommended given the risk of severe injury or death if a seizure was to occur.36

However, as this patient group is highly heterogeneous, counselling regarding exercise should be individualised and take into account both seizure type and frequency.33

Yoga

Recent studies have shown that yoga can significantly reduce seizure index and increase quality of life in people with epilepsy.39 Yoga also significantly improves parasympathetic parameters, indicating that yoga may have a role as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of autonomic dysfunction in patients with refractory epilepsy.40

Nutritional influences

Diets

Potentially beneficial dietary interventions should always include the identification and treatment of blood glucose dysregulation, the identification and elimination of allergenic foods and the avoidance of suspected triggers such as alcohol, artificial sweeteners, diet soft-drinks, energy drinks and MSG.11, 41, 42

Growth retardation is common amongst children with epilepsy and this appears to be primarily due to poor dietary intake. Approximately 30% of children with intractable epilepsy have been noted to have intakes below the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for Vitamins D, E and K, folate, calcium, linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid. It is the physician’s responsibility to be aware of this pattern of low nutrient intake and to educate families to provide an adequate diet or consider vitamin and mineral supplementation.43

Dietary treatments for epilepsy (ketogenic, modified Atkins, low glycaemic index diets) have been in continuous use since 1921. These dietary interventions have been well studied, with approximately 50% children having a 50% reduction in seizures after 6 months. Approximately one-third will attain >90% reduction in their seizures. It is important to note that the diet maintains its efficacy when provided continuously for several years. Furthermore, long-term benefits may be seen even when the diet is ceased after only a few months, indicating neuroprotective effects.44

Ketogenic diet (KD)

The KD is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet used to treat medically refractory epilepsy.45 A recent RCT in children with refractory epilepsies showed that the KD was superior to continuation of medical treatment in reducing seizure frequency in this population. The KD has also been used successfully in a variety of epilepsy syndromes, such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.46 Despite nearly a century of use, however, the mechanisms underlying its clinical efficacy remain unknown.47 As the KD is effective in syndromes of various aetiologies, this suggests there are multiple mechanisms of action.45,46–53 It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss these in detail, however, 4 such hypotheses include the pH, metabolic, amino acid and the ketone hypotheses.54 The KD is principally high in fat, has adequate protein and is low in carbohydrates (no more than 4:1 ratio weight of fat: combined protein/carbohydrate).

Chronic ketosis is thought to modify the TCA cycle to increase GABA synthesis in the brain, limit ROS generation and boost energy production in brain tissue.47, 55 Acetone is the principal ketone body elevated in the KD with demonstrated robust anticonvulsant properties. Recent research has shown that acetone enhances the anticonvulsant effects of valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine and phenobarbital without affecting their pharmokinetic or side-effect profiles.56 Indeed, therapeutic indices in animal models are comparable to or better than those of valproate, a standard broad-spectrum anticonvulsant.57

At least 15–20% patients using the KD experience a >50% reduction in seizure frequency. For this reason, the KD should be considered as an early treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy, not only as a ‘last resort’.58, 59, 60 Unfortunately, 10–40% discontinue this strict diet secondary to a lack of response or adverse side-effects. Available data indicates that genetic factors are likely to affect the efficacy of this diet.61

A recent blinded cross-over trial involved children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome placed on the KD with an addition of 60g glucose daily to negate the ketosis. This additional glucose did not significantly alter the frequency of EEG-assessed seizures, however, it did decrease the frequency of parent-reported ‘drop’ seizures during the follow-up period of 12 months. Fasting had significant effects on both seizures and EEG-assessed events.62

The efficacy of the KD develops over 1–3 weeks, suggesting that adaptive changes in gene expression are involved in its anticonvulsant effects.63 It has proven to be a valuable therapeutic option for children with drug-resistant focal epilepsy, particularly those with a recent deterioration of seizure control. Because of its rapid effects, the KD may also be a useful support to IV emergency drugs in such a situation.64

Modified Atkins diet

The modified Atkins diet is a less restrictive ketogenic diet which does not involve fasting and has no restrictions on calories, fluids or protein. The consumption of 10g/day of carbohydrates in children and 15g/day carbohydrates in adults is allowed whilst high fat foods are encouraged. Approximately 45% patients have 50–90% seizure reduction with 28% having >90% seizure reduction, results that are very similar to those produced by the KD.65 The KD appears to exert its seizure-reducing effects quicker than the modified Atkins diet, however, by 6 months the difference is no longer considered significant.59

Low glycaemic index diet (LGIT)

Children on the KD may exhibit poor weight gain and have lower blood glucose levels compared with children on standard balanced diets. One recent study reported on the efficacy, safety and tolerability of the LGIT in paediatric intractable epilepsy. Greater than 50% reduction from baseline seizure frequency was seen respectively in 42%, 50%, 54%, 64% and 66% of children at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. No significant changes were seen in BMI. Of the participants, 24% discontinued the LGIT secondary to its restrictiveness.66

Nutritional supplementation

Vitamins and minerals

Antioxidants

Neuronal hyperexcitability and excessive production of free radicals have been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of idiopathic epilepsy. As such, there is a possible role of antioxidants as an adjunct to AEDs for better seizure control.67, 68, 69

The pro-oxidant/antioxidant balance is modulated by both seizure activity and by AEDs.67 Gingival hyperplasia is a side-effect of some of these drugs and appears secondary to increased oxidative stress. Studies reveal reduced levels of superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol with elevated lipid peroxides in these patients.70 Oxidative stress after long-term treatment with valproate has only been found to occur in overweight children. This is important as it may contribute to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis that is of increased incidence in the adult life of many people with epilepsy.71 Antioxidant markers are again increased when valproate is ceased.72, 73

Plasma and RBC levels of the antioxidants Vitamins A, C and E, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase and selenium are markedly lower in epileptic patients compared with controls. These levels improve with supplementation.74, 75

Anti-epileptic medications may also deplete total body selenium stores and failure to give appropriate Se supplementation, especially to pregnant women taking valproate, may increase the risk of neural tube defects or other free radical mediated damage.76

Alpha-tocopherol is the antioxidant most studied with respect to reducing frequency of epileptic activity in both animal models and humans. Results have thus far been mixed and more studies are required before definitive recommendations can be made.77–86

Selenium deficiency has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of epilepsy.87 Recent studies have shown that topiramate and Vitamin E have protective effects on pentylenetetrazol-induced (PTZ-induced) nephrotoxicity by inhibition of free radicals and support of the antioxidant redox system.88 Similarly, topiramate and selenium exert protective effects on PTZ-induced brain injury and blood toxicity by inhibiting free radical production, regulating calcium-dependent processes and supporting the antioxidant redox system.89, 87

Better regulation of the lipid peroxidation and antioxidants and fewer disturbances in mineral metabolism have been observed with patients on monotherapy vs polytherapy and with carbemazepine vs valproate therapy.90

Zinc

Zinc is a fundamental trace element present in high levels in many structures of the limbic circuitry. Altered zinc homeostasis appears to be associated with epilepsy, however, the definitive role of zinc as a neuromodulator in synapses is still uncertain.91–96 Intracellular zinc homeostasis is sensitive to pathophysiological environmental changes such as acidosis, inflammation and oxidative stress.97 Zinc itself can also induce oxidative stress by promoting mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species.98 Studies have revealed that zinc chelation decreases the duration of behavioural seizures and electrical after-discharges and the duration of EEG spikes frequency.99

Animal studies reveal that zinc deficiency is associated with an increase in epileptic seizures and hippocampal cell death. This appears to happen through abnormal calcium metabolism.100, 101, 102

Other vitamins and minerals

Most AEDs reduce folic acid levels, thereby raising homocysteine (Hcy) levels. Hcy, however, is a convulsing agent resulting in heightened seizure recurrence and intractability to AEDs. Furthermore, AEDs can disturb lipid metabolism with subsequent hypercholesterolaemia and dyslipidaemia, with additional altered uric acid metabolism. As such, routine supplementation with folic acid, Vitamin B12, B6, C, E and beta-carotene for all those on AEDs becomes increasingly important.103

A recent Cochrane review has found that thiamine improves neuropsychological and cognitive functions in patients with epilepsy. In the same review, Vitamin D was found to improve bone mineral density in those taking AEDs. However, more trials are obviously needed.11, 77

A recent systematic review has demonstrated that manganese deficiency can also be accompanied by seizures in both animals and humans. As yet, it is unclear as to whether this is a cause or effect of the convulsions, justifying the need for more intensive research.104

Individuals with seizures may also have lower levels of vitamin A, B1, B12, C, folate, magnesium, selenium, zinc, carnitine, carnosine, choline and possibly serine. Furthermore, disorders of metabolism involving vitamin B6, D, calcium and tryptophan may play important roles.105 Seizure type and number of stimuli seem to be the determinant factors for changes in zinc, copper and magnesium levels.106, 107, 108 There has also been found a statistically significant increase in serum copper levels in patients with epilepsy compared with controls.109

Other supplements

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)

A higher dietary intake of PUFAs may be partially responsible for the potent anticonvulsant effects of the KD as concentrations of both ketone bodies and PUFAs have been found to be increased in the CSF and plasma of patients.2, 110 Animal studies have shown that increased intake of PUFAs may reduce the risk of epileptic seizures through various biochemical mechanisms, including PUFA-induced openings of voltage-gated potassium channels.2, 110 Omega-3 supplementation has also been shown to prevent status epilepticus-associated neuropathological changes in the hippocampus in animals.111

Some AEDs, such as carbemazepine, are known to decrease levels of long-chain omega-3 PUFAs, particularly DHA, and thereby increase the risk of cardiovascular events (arrhythmias, sudden unexplained death in epilepsy) in this population. Following 3 months of omega-3 supplementation (1g EPA/0.7g DHA daily), plasma and RBC levels increased significantly and patients taking carbemazepine (or not) exhibited a more favourable cardiovascular profile.112, 113, 114 Furthermore, omega-3 supplementation may be associated with reduced membrane phospholipid breakdown in the brain with an improvement in brain energy metabolism.115

Recent animal studies with Evening Primrose Oil (EPO) have conflicted previous thoughts that EPO could potentiate seizures. Rather, prolonged supplementation of linoleic acid and gamma-linolenic acid appears to exert anticonvulsant activity through various biochemical pathways.116 Nevertheless, more research is warranted to ensure the safety of EPO in epileptic patients.

Although PUFAs reduce seizures in several animal models, available data regarding the effects of supplementation with PUFAs (1–3g EPA/DHA daily) in epileptic patients reveal mixed results with respect to seizure frequency.114, 117, 118, 119, 120 Therefore, more research is required before PUFAs can be presented as a treatment option for epilepsy.2

Amino acids

Because of the high proportion of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, new hypotheses about the mechanisms of pharmacoresistance are actively being researched. In particular, the role of brain serotonin in epilepsy has been turned upside down in recent years with current thoughts being that serotonin has an anti-epileptic effect. Serotonin receptors are expressed in almost all networks involved in epilepsies. Some SSRIs, such as Fluoxetine, have indeed improved seizure control and some AEDs have recently been found to increase endogenous serotonin levels.121, 122, 123

Tryptophan

Tryptophan, an essential amino acid, is the only brain precursor of serotonin. It has been estimated that patients with epilepsy have approximately 30% lower brain intake of tryptophan compared with controls. Increasing plasma tryptophan results in increased brain synthesis of serotonin. However, there is competition between tryptophan and other large neutral amino acids (LNAAs) for entry across the blood brain barrier. Whey proteins that are high in tryptophan but lower in other LNAAs are currently being tested as a combination with anti-epileptic medications.121

Taurine

Taurine is one of the most abundant free amino acids which is found mainly in excitable tissues. Taurine is required for the synthesis of GABA, one of the major inhibitory neurotransmitters in the limbic system.124 For this reason, drugs that target GABA receptors are the mainstay of treatment of seizures with the recent transplantation of GABA-producing cells effectively reducing seizures in several well-established models.125, 126 Humans are mostly dependent on dietary sources of taurine and previous studies have shown that supplementation can protect against oxidative stress, neurodegenerative diseases and atherosclerosis.127, 128

There have been multiple animal studies demonstrating that taurine-fed animals have increased expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase, the enzyme responsible for GABA synthesis, with increased levels of GABA. They also have a higher threshold for seizure onset compared to controls.124 Furthermore, increased taurine levels in the hippocampus improve membrane stabilisation, significantly reducing neuronal cell death and favouring recovery after neuronal hyperactivity.129, 130, 131 Acute injections of taurine also result in a reduction or total absence of tonic/clonic seizures with reduced duration and mortality rate in animal models.130

Carnosine

Carnosine is a naturally occurring compound that is made from beta-alanine and l-histidine. It has many features of a neurotransmitter and can act as both a neuromodulator and neuroprotective agent. It may indirectly influence neuronal excitability by modulating the effects of zinc and copper.132, 133, 134 Recent findings indicate that carnosine has a significant anticonvulsant effect on penicillin-induced epilepsy in animals. Thus it may be a potential anticonvulsant treatment for clinical therapy of epilepsy in the future.135

Indeed, the concentrations of many amino acids, including alanine, arginine, glutamate, aspartate, carnitine as well as taurine, impact upon seizure activity in animal models. Although not yet well understood, there appears to be a specific role of these amino acids in the shaping of a new equilibrium between excitatory and inhibitory processes in the hippocampus.11, 136

Herbal medicines

Herbal medicine has been used for centuries in many cultures around the world for the treatment of epilepsy. Today, many people try herbal therapies for better control of seizures or to counteract adverse effects from AEDs. Indeed, herbs are considered by many to be safe and effective and use them without the knowledge of their physician.139 However, many herbs can increase the risk for seizures through intrinsic anticonvulsant properties, contamination by heavy metals or by affecting cytochrome P450 enzymes and P-glycoproteins, altering AED disposition. Health care professionals should therefore always inquire as to the use of herbal preparations in order to prevent complications with the combined regime.140

Well-designed clinical trials of herbal therapies for epilepsy are scarce. However, based on animal studies and numerous anecdotal observations of clinical benefits in humans, further research is certainly warranted.139, 140

Some traditional medicinal herbs have been found to exert anticonvulsant effects by exhibiting significant affinity for the GABA (A) receptor benzodiazepine binding site. These include flavonoid derivatives from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Artemesia herba-alba, Melissa officinalis and Salvia triloba.141, 142 Gingko biloba possesses the capacity to both induce and inhibit seizures.143

Some Chinese herbs, including Chaihu-longu-muli-tang, have both anti-epileptic and antioxidant potential. It is thought that the reduction in seizure frequency may be related to the antioxidant effects of the herbs.144 Shitei-To is another TCM formulation that may have therapeutic effects in the prevention of secondarily generalised seizures. It is made from 3 medicinal herbs: Shitei (calyx of Diospyros kaki L.f), Shokyu (rhizome of Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and Choji (flowerbud of Sysygium aromaticum).145

Curcumin has also been recently shown to significantly prevent generalisation of electro-clinical seizure activity as well as the pathogenesis of iron-induced epileptogenesis.146, 147

Physical therapies

Acupuncture

A recent Cochrane review has investigated the use of acupuncture in epilepsy. Compared to phenytoin, patients who received needle acupuncture appeared more likely to achieve 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Compared to valproate, catgut implantation at acu-points appeared more likely to result in 75% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. However, the studies were of poor methodological quality and it was concluded that current evidence does not support acupuncture as a treatment for epilepsy.148 Results are generally mixed and as such, more rigorous trials are warranted to establish the role of acupuncture in epilepsy.149–152

There have been multiple animal studies demonstrating the anticonvulsant effects of electro-acupuncture.153, 154 It has been shown that stimulation of acupuncture points on the extremities results in stimulation of the vagus nerve and this may partially explain its neuroprotective effects.155

As stated previously, taurine may play an inhibitory role against epilepsy by its action as an inhibitory amino acid in the central nervous system. Recent animal studies have shown that electro-acupuncture may partially inhibit epilepsy by up-regulating the concentration of taurine transporter to increase the release of taurine.156, 157, 158 Exogenous taurine further enhances the anti-convulsive effect of electro-acupuncture.159

Electro-acupuncture may also exert its anti-seizure effects by elevating melatonin levels in the pineal gland and hippocampus and reducing nitric oxide synthases.11, 160, 161,

Chiropractic

A systematic review from 1970–2000 has concluded that chiropractic care may represent a valid non-pharmaceutical health care approach for paediatric epileptic patients. Case reports and anecdotal evidence suggest that correction of potential upper cervical vertebral subluxation complexes might be most beneficial. Further investigation into upper cervical trauma as a contributing factor to epilepsy should be pursued.162, 163, 164

Reiki

There has been only 1 published study of inferior quality on epilepsy and reiki.165 In a randomly selected sample population with refractory epilepsy from a single neurology department, data were collected on 15 patients before treatment and 3 months after treatment. The participants were aged 20–30 years and had no comorbidities. Seizure frequency at the end of treatment was reduced and there was also a significant increase in serum magnesium.

Conclusion

Epilepsy is the most common neurological disorder in the world, with important and serious physical, psychological, social and economic costs. Epilepsy is widespread across the globe, with the World Health Organization estimating that approximately 85% of the people afflicted with this disorder live in developing countries.166

Epilepsy is a difficult illness to control — up to 35% of patients do not respond fully to traditional medical treatments.167 This is a primary reason as to why many sufferers choose to rely on or incorporate CAM into their treatment regimens. Epileptics can employ diverse modalities to prevent and treat seizures, such as: mind–body medicines, such as relaxation therapy, hypnosis and CBT; biologic-based medicine, such as herbal remedies, dietary supplements, and manipulative-based medicine such as chiropractic, acupuncture, massage, cranio-sacral therapies, homeopathy, ketogenic diets and aromatherapy.168 CAM therapies should be embraced as having a potentially important role in the integrated holistic management of patients with epilepsy.

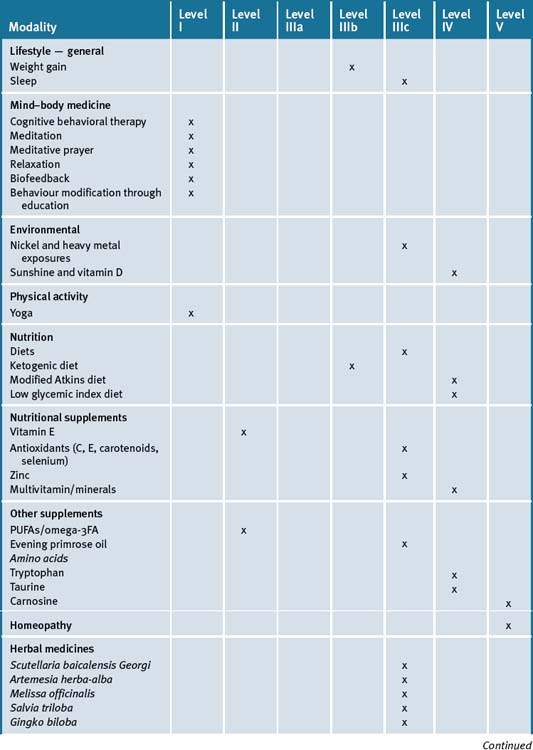

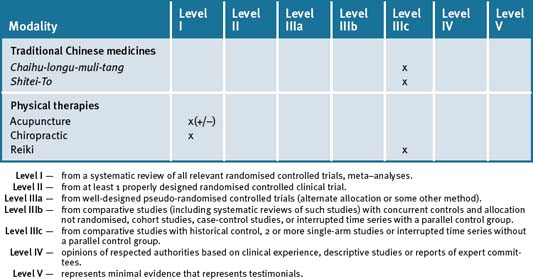

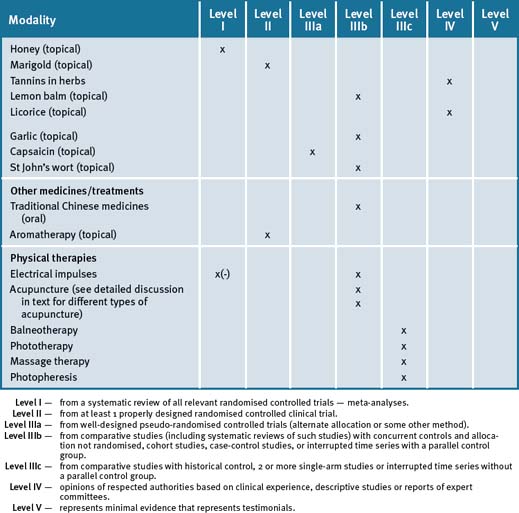

Table 15.1 summarises the level of evidence for some CAM therapies for epilepsy.

Clinical tips handout for patients — epilepsy

1 Lifestyle advice

Sleep

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind-body medicine

4 Environment

5 Dietary modification

6 Physical therapies

7 Supplementation

Folate

1 Cascino G.D. When drugs and surgery don’t work. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 9):79-84.

2 Farman A.H., Lossius M.I., Nakken K.O., Tidsskr. PUFAs and Epilepsy. Nor Laegeforen. 2009;129(1):26-28.

3 Vicente-Hernandez M., Garcia-garcia P., Gil-Nagel A., et al. Therapeutic approach to epilepsy from the nutritional view: current status of dietary treatment. Neurologia. 2007;2298:517-525.

4 Perucca P., Carter J., Vahle V., et al. Adverse antiepileptic drug effects: towards a clinically and neurobiologically relevant taxonomy. Neurology. 2009;72(14):1223-1229.

5 Theodore W.H., Spencer S.S., Wiebe S., et al. Epilepsy in North America: a report prepared under the auspices of the global campaign against epilepsy, the International Bureau for Epilepsy, the International League Against Epilepsy, and the World Health Organization. Epilepsia. 2006;47(10):1700-1722.

6 Schachter S.C. CAM Therapies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(2):184-189.

7 Ricotti V., Delanty N. Use of CAM in epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6(4):347-353.

8 Gross-Tsur V., Lahad A., Shalev R.S. Use of complementary medicine in children with ADHD and epilepsy. Paediatr Neurol. 2003;29(1):53-55.

9 Peebles C.T., McAuley J.W., Roach J. Alternative medicine use by patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1(1):74-77.

10 Tandon M., Prabhaker S., Pandhi P. Pattern of use of CAM in epileptic patients in a tertiary care hospital in India. Pharmacoepidemiol Dug Saf. 2002;11(6):457-463.

11 Gaby A.R. Natural approaches to epilepsy. Altern Med Rev. 2007;12(1):9-24.

12 Ben-Menachem E. Weight issues for people with epilepsy–a review. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 9):42-45.

13 Rocamora R., Sanchez-Alvarez J.C., Salas-Puig J. The relationship between sleep and epilepsy. Neurologist. 2008;14(6 Suppl. 1):S35-S43.

14 Mendez M., Radtke R.A. Interactions between sleep and epilepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(2):106-127.

15 Dinner D.S. Effect of sleep on epilepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19(6):504-513.

16 Shouse M.N., Farber P.R., Staba R.J. Physiological basis: how NREM sleep components can promote and REM sleep components can suppress seizure discharge propagation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111(Suppl 2):S9-S18.

17 Shouse M.N., Scordato J.C., Farber P.R. Sleep and arousal mechanisms in experimental epilepsy: epileptic components of NREM and antiepileptic components of REM sleep. Ment retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10(2):117-121.

18 Kotagal P., Yardi N. The relationship between sleep and epilepsy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2008;15(2):42-49.

19 DeRoos S.T., Chillag K.L., Keeler M., et al. Effects of sleep deprivation on the paediatric EEG. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):703-708.

20 Sebit M.B., Mielke J. Epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa: its socio-demography, aetilogy, diagnosis and EEG characteristics in Harare, Zimbabwe. East afr Med J. 2005;82(3):128-137.

21 Kwan P., Yu E., Leung H., et al. Association of subjective anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance with QOL ratings in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008 Dec 15. Epub ahead of print

22 Cohen M.H. Regulation, religious experience and epilepsy: a lens on comp therapies. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(6):602-606.

23 Gross R.A. A brief history of epilepsy and its therapy in the Western Hemisphere. Epilepsy Res. 1992;12(2):65-74.

24 Millogo A., Ratsimbazafy V., Nubukpo P., et al. Epilepsy and traditional medicine in Bobo-Dioulasso. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109(4):250-254.

25 Arias A.J., Steinberg K., Banga A., et al. illness, Systematic review of the efficacy of meditation techniques as treatments for mental. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(8):817-832.

26 Lansky E.P., St Louis E.K. TM: a doubl-edged wsord in epilepsy? Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9(3):394-400.

27 Ramaratnam S., Baker G.A., Goldstein L.H. Psychological treatments for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2008 Jul 16. CD002029

28 Weinstein R.S., Bryce G.F., Sappington L.J., et al. Decreased serum ionised calcium and normal Vitamin D metabolite levels with anticonvulsant drug treatment. J Clin endocrin Metab. 1984;58(6):1003-1009.

29 Williams C., Netzloff M., folkerts L., et al. Vit D metabolism and anticonvulsant therapy: effect of sunshine on incidence of osteomalacia. Soth Med J. 1984;77(7):834-836. 842

30 Denays R., Kumba C., Lison D., et al. First epileptic seizure induced by occupational nickel poisoning. Epilepsia. 2005;46(6):961-962.

31 Arrieta O., Palencia G., Garcia-Arenas G., et al. Prolonged exposure to lead lowers the threshold of pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in rats. Epilepsia. 2005;46(10):1599-1602.

32 Ruegg S., Hunziker P., Marsch S., et al. Association of environmental factors with the onset of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(1):66-73.

33 Nakken K.O. Should people with epilepsy exercise? Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2000;120(25):3051-3053.

34 Ablah E., Haug A., Konda K., et al. Exercise and epilepsy: a survey of Midwest epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(1):162-166.

35 Arida R.M., Scorza C.A., Schmidt B., et al. Physical activity in SUDEP: much more than a simple sport. Neurosci Bull. 2008;24(6):374-380.

36 Howard G.M., Radloff M., Sevier T.L. Epilepsy and sports participation. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2004;3(1):15-19.

37 Arida R.M., Cavalheiro E.A., da Silva A.C., et al. Physical activity and epilepsy: proven and predicted benefits. Sports Med. 2008;38(7):607-615.

38 Arida R.M., Scorza F.A., Scorza C.A., et al. Is physical activity beneficial for recovery in TLE? Evidences from animal studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(3):422-431.

39 Lundgren T., Dahl J., Yardi N., et al. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and yoga for drug-refractory epilepsy: a RCT. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(1):102-108.

40 Sathyaprabha T.N., Satishchandra P., Pradhan C., et al. Modulation of cardiac autonomic balance with adjuvant yoga therapy in pts with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(2):245-252.

41 Mortelmans L.J., Van Loo M., De Cauwer H.G., et al. Seizures and hyponatremia after excessive intake of diet coke. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(1):51.

42 Iyadurai S.J., Chung S.S. Nutrient intake of children with intractable epilepsy compared with healthy children. New onset seizures in adults: possible association with consumption of popular energy drinks. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10(3):504-508.

43 Volpe S.L., Schall J.I., Gallagher P.R., et al. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(6):1014-1018.

44 Kossoff E.H., Rho J.M. KD: Evidence for short and long term efficacy. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):406-414.

45 Weinshenker D. The contribution of NorAd and orexigenic neuropeptides to the anticonvulsant effect of the KD. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):104-107.

46 Hartman A.L. Does the effectiveness of the KD in different epilepsies yield insights into its mechanisms? Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):53-56.

47 Bough K.J., Rho J.M. Anticonvulsant mechanisms of the KD. Epilepsia. 2007;48(1):43-58.

48 Rho J.M., Sankar R. The KD in a pill: is this possible? Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):127-133.

49 Nikanorova M., Miranda M.J., Atkins M., et al. KD in the treatment of refractory continuous spikes and waves during slow sleep. Epilepsia. 2009 Feb 12. Epub ahead of print

50 Masino S.A., Geiger J.D. The KD and epilepsy: Is adenosine the missing link? Epilepsia. 2009;50(2):332-333.

51 Noh H.S., Kim Y.S., Choi W.S. Neuroprotective effects of the KD. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):120-123.

52 Allen C.N. Circadian rhythms, diet and neuronal excitability. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):124-126.

53 Yamada K.A. Calorie restriction and glucose regulation. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):94-96.

54 Nylen K., Likhodii S., Burnham W.M. The KD: proposed mechanisms of action. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):402-405.

55 Bough K. Energy metabolism as part of the anticonvulsant mechanism of the KD. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):91-93.

56 Zarnowska I., Luszczki J.J., Zarnowski T., et al. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions between common AED and acetone, the chief anticonvulsant ketone body elevated in the KD in mice. Epilepsia. 2008 Oct 24. Epub ahead of print

57 Likhodii S., Nylen K., Burnham W.M. Acetone as an anticonvulsant. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):83-86.

58 Nordli D.R.Jr. The KD, four score and seven years later. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5(1):12-13.

59 Porta N., Vallee L., Boutry E., et al. Comparison of seizure reduction and serum FA levels after receiving the ketogenic and modified Atkins diet. Seizure. 2009 Feb 2. [ Epub ahead of print]

60 Kozak N., Csiba L. Dietary aspects of epilepsy. Ideggyogy Sz. 2007;60(5–6):234-238.

61 Dutton S.B., Escayg A. Genetic influences on KD efficacy. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):67-69.

62 Freeman J.M. The KD: additional information from a crossover study. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(4):509-512.

63 Bough K. Energy metabolism as part of the anticonvulsant mechanism of the KD. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):91-93.

64 Villeneuve N., Pinton F., Bahi-Buisson N., et al. The KD improves recently worsened focal epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(4):276-281.

65 Kossoff E.H., Dorward J.L. The Modified Atkins Diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):37-41.

66 Muzykewicz D.A., Lyczkowski D.A., Memon N., et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of the LGIT in paediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009 Feb 12. Epub ahead of print

67 Devi P.U., Manocha A., Vohora D. Seizures, antiepileptics, antioxidants and ox stress: an insight for researchers. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9(18):3169-3177.

68 Hayashi M. Ox stress in developmental brain disorders. Neuropathology. 2009;29(1):1-8.

69 Gupta R.C., Milatovic D., Dettbarn W.D. Depletion of energy metabolites following acetlycholinesterase inhibitor-induced status epilepticus: protection by anti-oxidants. Neurotoxicogy. 2001;22(2):271-282.

70 Sobaniec H., Sobaniec W., Sendrowski K., et al. Antiox activity of blood serum and saliva in patients with periodontal disease treated due to epilepsy. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52(Suppl 1):204-206.

71 Hamed S.A., Nabeshima T. The high atherosclerotic risk among epileptics: the atheroprotective role of multivitamins. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98(4):340-353.

72 Verrotti A., Scardapane A., Franzoni E., et al. Increased ox stress in epileptic children treated with valproic acid. Epilepsy Res. 2008;78(2–3):171-177.

73 Verrotti A., Greco R., Latini G., et al. Obesity and plasma concentrations of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene in epileptic girls treated with valproate. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79(3):157-162.

74 Liao K.H., Mei Q.Y., Zhou Y.C. Determination of anti-ox in plasma and RBC in pts with epilepsy. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue ban. 2004;29(1):72-74.

75 Sudha K., Rao A.V., Rao A. Ox stress and antioxidants in epilepsy. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;303(1–2):19-24.

76 Gutierrez-Alvarez A.M., Moreno C.B., Gonzalez-Reyes R.E. Changes in Se levels in epilepsy. Rev Neurol. 2005;40(2):111-116.

77 Ranganathan L.N., Ramaratnam S. Vitamins for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst rev. (2):2005. CD004304

78 Ayyildiz M., Yildirim M., Agar E. The effects of Vit E on penicillin-induced epileptiform activity in rats. Exp brain Res. 2006;174(1):109-113.

79 Ribeiro M.C., de Avila D.S., Schnider C.Y., et al. Alpha-tocopherol protects against pentylenetetrazol and methylmalonite induce convulsions. Epilepsy Res. 2005;66(1–3):185-194.

80 Komatsu M., Hiramatsu M. The efficacy of an antioxidant cocktail on lipid peroxide level and SOD activity in aged rat brain and DNA damage in iron-induced epileptogenic foci. Toxicology. 2000;148(2–3):143-148.

81 Rauca C., Wiswedel I., Zerbe R., et al. The role of SOD and alpha-tocopherol in the devt of seizures and kindling induced by pentylenetetrazol-influence of the radical scavenger alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butyl nitrone. Brain Res. 2004;1009(1–2):203-212.

82 Cao L., Xu J., Lin Y., et al. Autophagy is upregulated in rats with status epilepticus and partly inhibited by Vitamin E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379(4):949-953.

83 Oztas B., Kilic S., Dural E., et al. Influence of antioxidants on the BBB permeability during epileptic seizures. J Neurosci res. 2001;66(4):674-678.

84 Frantseva M.V., Perez Velazquez J.L., Tsoraklidis G., et al. Ox stress is involved in seizure-induced neurodegeneration in the kindling model of epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2000;97(3):431-435.

85 Ogunmekan A.O., Hwang P.A. A randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of D-alpha-tocopheryl actate (vitamin E) as add-on therapy, for epilepsy in children. Epilepsia. 1989;30(1):84-89.

86 Raju G.B., Behari M., Prasad K., et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of D-alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) as add-on therapy in uncontrolled epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1994;35(2):368-372.

87 Kutluhan S., Naziroglu M., Celik O., et al. Effects of Se and TPM on lipid peroxidation and anti-oxidant vitamin levels in blood of PTZ-induced epileptic rats. Biol Trace Elem res. 2009 Jan 6. Epub ahead of print

88 Armagan A., Kutluhan S., Yilmaz M., et al. Topiramate and Vitamin E modulate antiox enzyme activities, nitric oxide and lipid peroxidation levels in pentylenetetrazol-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxic. 2008;103(2):166-170.

89 Naziroglu M., Kutuhan S., Yilmaz M. Se and TPM modulates brain microsomal ox stress values, Ca2+-ATPase activity and EEG records in PTZ-induced seizures in rats. J MZembr Biol. 2008;22591–3:39-49.

90 Hamed S.A., Abdellah M.M., El-Melagy N. Blood levels of tace elements, electrolytes and ox stress/anti-ox systems in epileptic pts. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;96(4):465-473.

91 Moreno C.B., Gutierrez-Alvarez A.M., Gonzalez-Reyes R.E. Zn and epilepsy: Is there a causal relation between them? Rev Neurol. 2008;42(12):754-759.

92 Domingeuz M.I., Blasco-Ibanez J.M., Crespo C., et al. Neural overexcitation and implication of NMDA and AMPA receptors in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy implying zinc chelation. Epilepsia. 2006;4795):887-899.

93 Takeda A., Itoh H., Hirate, et al. Region-specific loss of zinc in the brain in PTZ-induced seizures and seizure susceptibility in Zn deficiency. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70(1):41-48.

94 Mathie A., Sutton G.L., Clarke C.E., et al. Zn and Cu: pharmacological probes and endogenous modulators of neuronal excitability. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111(3):567-583.

95 Horning M.S., Trombley P.Q. Zn and Cu influence excitability of rat olfactory bulb neurons by multiple mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86(4):1652-1660.

96 Levenson C.W. Zn supplementation: neuroprotective or neurotoxic? Nutr Rev. 2005;63(4):122-125.

97 Capasso M., Jeng J.M., Malavolta M., et al. Zn dyshomeostasis: a key modulator of neuronal injury. J alzheimers Dis. 2005;8(2):93-108.

98 Frazzini V., Rockabrand E., Mocchegiani E., et al. Ox stress and brain aging: is zinc the link? Biogerontology. 2006;7(5–6):307-314.

99 Foresti M.L., Arisi G.M., Fernandaz A., et al. Chelatable Zn modulatesx excitability and seizure duration in the amygdala rapid kinding model. Epilepsy Res. 2008;79(2–3):166-172.

100 Takeda A., Tamano H., Nagayoshi A., et al. Increase in hippocampal death after treatment with kainate in zinc deficiency. Neurochem Int. 2005;47(8):539-544.

101 Takeda A., Itoh H., Nagayoshi A., et al. Abnormal calcium mobilisation in hippocampal slices of epileptic animals fed a zinc deficient diet. Epilepsy Res. 2009;83(1):73-80.

102 Chwiej J., Winiarski W., Ciarach M., et al. The role of trace elements in the pathogenesis and progress pf pilocarpine-induced epileptic seizures. J Biol Inorg chem. 2008;13(8):1267-1274.

103 Hamed S.A., Nabeshima T. The high atherosclerotic risk among epileptics: the atheroprotective role of MV. J pharmacol sci. 2005;98(4):340-353.

104 Gonzalez-reyes R.E., Gutierrez-Alvarez A.M., Moreno C.B. Mn and epilepsy: a SR of the literature. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53(2):332-336.

105 Thiel R.J., Fowkes S.W. Downs Syndrome and Epilepsy-a nutritional connection? Med Hypotheses. 2004;62(1):35-44.

106 Doretto M.C., Simoes S., Paiva A.M., et al. Zn, Mg and Cu profiles in 3 experimental models of epilepsy. Brain Res. 2002;956(1):166-172.

107 Ilhan A., Uz E., Kali S., et al. Serum and hair trace element levels in patients with epilepsy and healthy subjects: does the AEDs affect the element concentrations of hair? Eur J Neurol. 1999;6(6):705-709.

108 Motta E., Miller K., Ostrowska Z. Conc of copper and ceruloplasmin in serum of patients treated for epilepsy. Wiad Lek. 1998;51(3–4):156-161.

109 Ilhan A., Ozerol E., Gulec M., et al. The comparison of nail and serum trace elements in patients with epilepsy and healthy subjects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):99-104.

110 Xu X.P., Erichsen D., Borjesson S.I., et al. PUFAs and CSF from children on the KD open a voltage-gated K channel: a putative mechanism of antiseizure action. Epilepsy Res. 2008;80(1):57-66.

111 Ferrari D., Cysneiros R.M., Scorza C.A., et al. Neuroprotective activity of n-3 FAs against epilepsy-induced hippocampal damage: Quantification with immunohistochemical for Ca-binding proteins. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(1):36-42.

112 Yuen A.W., Sander J.W., Flugel D., et al. RBC and plasma FA profiles in patients with epilepsy: does carbemazepine affect Omega-3 FA concentrations? Epilepsy Behaviour. 2008;12(2):317-323.

113 Dahlin M., Hjelte L., Nilsson S., et al. Plasma PUFAs are influenced by a KD enriched with n-3 FAs in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2007;73(2):199-207.

114 DeGeorgio C.M., Miller P., Meymandi S., et al. Omega-3 FAs for epilepsy, cardiac risk factors and risk of SUDEP: clues from a pilot, double-blind exploratory study. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(4):681-684.

115 Puri B.K., Koepp M.J., Holmes J., et al. A 31 P neurospectoscopy study of n-3 LCPUFA intervention with EPA and DHA in patients with chronic refractory epilepsy. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;77(2):105-107.

116 Puri B.K. The safety of EPO in epilepsy. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent fatty Acids. 2007;77(2):101-103.

117 Taha A.Y., Huot P.S., Reza-Lopez S., et al. Seizure resistance in fat-1 transgenic mice endogenously synthesising high levels of n-3 PUFAs. J Neurochem. 2008;105(2):380-388.

118 Pifferi F., Tremblay S., Plourde M., et al. Ketones and brain function: possible link to PUFAs and availability of a new brain PET tracer, 11C-acetoacetate. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):76-79.

119 Borges K. Mouse models: the KD and PUFAS. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 8):64-66.

120 Bromfield E., Dworetsky B., Hurwitz S., et al. A randomised trial of PUFAs for refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(1):187-190.

121 Mainardi P., Leonardi A., Albano C. Potentiation of brain serotonin activity may exhibit seizures, especially in drug-resistant epilepsy. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(4):876-879.

122 Bagdy G., Kecskemeti V., Riba P., et al. Serotonin and epilepsy. J Neurochem. 2007;100(4):857-873.

123 Serotonergic Isaac M. 5-HT2C receptors as a potential therapeutic target for the design of antiepileptic drugs. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5(1):59-67.

124 El idrissi A., L’Amoreaux W.J. Selective resistance of taurine-fed mice to isoniazid-potentiated seizures: in vivo functional test for the activity of glutamic acid decarboxylase. Neuroscience. 2008;156(3):693-699.

125 Galanopoulou A.S. GABA(A) Receptors in normal development and seizures: friends or foe? Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6(1):1-20.

126 Thompson K. Transplantation of GABA-Producing cells for seizure control in models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):284-294.

127 Bouckenooghe T., Remacle C., Reusens B. Is taurine a functional nutrient? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9(6):728-733.

128 Gupta R.C., Win T., Bittner S. Taurine analogues; a new class of therapeutics: retrospect and prospects. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12(17):2021-2039.

129 Baran H. Alterations of taurine in the brain of chronic kainic acid epilepsy model. Amino Acids. 2006;31(3):303-307.

130 El Idrissi A., messing J., Scalia J., et al. Prevention of epileptic seizures by taurine. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;526:515-525.

131 Junyent F., Utrera J., Romera R., et al. Prevention of epilepsy by taurine treatments in mice experimental model. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(6):1500-1508.

132 Trombley P.Q., Horning M.S., Blakemore L.J. Carnosine modulates zinc and copper effects on amino acid receptors and synaptic transmission. Neuroreport. 1998;9(15):3503-3507.

133 Trombley P.Q., Horning M.S., Blakemore L.J. Interactions between carnosine and zinc and copper: implications for neuromodulation and neuroprotection. Biochemistry (Mosc. 2000;65(7):807-816.

134 Horning M.S., Blakemore L.J., Trombley P.Q. Endogenous mechanisms of neuroprotection: role of zinc, copper and carnosine. Brain Res. 2000;852(1):56-61.

135 Kozan R., sefil F., Bagirici F. Anticonvulsant effect of carnosine on penicillin-induced epileptiform activity in rats. Brain Res. 2008 Aug 16. Epub ahead of print

136 Szyndler J., Maciejak P., Turzynska D., et al. Changes in the concentration of amino acids in the hippocampus of pentylenetetrazole-kindled rats. Neurosci lett. 2008;439(3):245-249.

137 Varshney J.P. Clinical management of idiopathic epilepsy in dogs with homeopathic Belladonna 200C: a case series. Homeopathy. 2007;96(1):46-48.

138 Mathie R.T., Hansen L., Elliott M.F., et al. Outcomes from homeopathic prescribing in vet practice: a prospective research-targeted, pilot study. Homeopathy. 2007;96(1):27-34.

139 Schacter S.C. Botanics and herbs: a traditional approach to treating epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):415-420.

140 Samuels N., Finkelstein Y., Singer S.R., et al. Herbal medicine and epilepsy: proconvulsive effects and interactions with AEDs. Epilepsia. 2008;49(3):373-380.

141 Huen M.S., Leung J.W., ng W., et al. 5,7-dihydroxy-6-methoxyflavone, a benzodiazepine site ligand isolated grom Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, with selective antagonistic properties. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(1):125-132.

142 Salah S.M., Jager A.K. Screening of traditionally used Lebanese herbs for neurological activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97(1):145-149.

143 Harms S.L., Garrard J., Schwinghammer P., et al. Gingko biloba use in nursing home elderly with epilepsy or seizure disorder. Epilepsia. 2006;47(2):323-329.

144 Hung-Ming W., Liu C.S., Tsai J.J., et al. Antiox and anti-convulsant effect of a modified formula of chaihu-longu-muli-tang. Am J Chin Med. 2002;30(2–3):339-346.

145 Minami E., Shibata H., Nomoto M., et al. Effect of shitei-to, a TCM formulation, on PZT-induced kindling in mice. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(1):69-72.

146 Jyoti A., Sethi P., Sharma D. Curcumin protects against electrobehavioural progression of seizures in the iron-induced experimental model of epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(2):300-308.

147 Sumanont Y., Murakami Y., Tohda M. Effects of Mn complexes of curcumin and diacetylcurcumin on kainic acid-induced neurotoxic responses in the rat hippocampus. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(9):1732-1739.

148 Cheuk D.K., Wong V. Acupuncture for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2008. CD005062

149 Lee H., Park H.J., Park J. Acupuncture application for neurological disorders. Neurol Res. 2007;29(Suppl 1):S49-S54.

150 Chen X.H., Yang H.T. effects of acupuncture under guidance of qi street theory on endocrine function in the patient of epilepsy. Zhongguo Zhen jiu. 2008;28(7):481-484.

151 Yongxia R. Acupuncture treatment of Jacksonian epilepsy-a report of 98 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2006;26(3):177-178.

152 Zhao H.Y., Li J. Clinical application of ‘8 acupoints at the head’ by Professer QIN Liang-fu. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007;27(10):745-748.

153 Shu J., Liu R.Y., Huang X.F. Efficacy of ear-point stimulation on experimentally induced seizure. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2005;30(1–2):43-52.

154 Guo J., Liu J., Fu W., et al. The effect of EA on spontaneous recurrent seizure and expression of GAD(67 mRNA in dentate gyrus in a rat model of epilepsy. Brain Res. 2008;1188:165-172.

155 Cakmak Y.O. Epilepsy, EA and the nucleus of the solitary tract. Acupunct Med. 2006;24(4):164-168.

156 Jin H.B., Li B., Gu J., et al. EA improves epileptic seizures induced by kainic acid in taurine-depletion rats. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2005;30(3–4):207-217.

157 Shu J., Liu R.Y., Huang X.F. The effects of ear-point stimulation on the contents of somatostatin and amino acid neurotransmitters in brain of rat with experimental seizure. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2004;29(1–2):43-51.

158 Yang R., Li Q., Guo J.C., et al. Taurine participates in the anticonvulsant effect of EA. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;583:389-394.

159 Li Q., Guo J.C., Jin H.B., et al. Involvement of taurine in penicillin-induced epilepsy and anti-convulsion of acupuncture: a preliminary report. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2005;30(1–2):1-14.

160 Chao D.M., Chen G., Cheng J.S. Melatonin might be one possible medium of EA anti-seizures. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2001;26(1–2):39-48.

161 Yang R., Huang Z.N., Cheng J.S. Anticonvulsion effect of acupuncture might be related to the decrease of neuronal and inducible nitric oxide synthases. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2000;25(3–4):137-143.

162 Pistolese R.A. Epilepsy and seizure disorders: a review of the literature relative to chiropractic care of children. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(3):199-205.

163 Alcantara J., Heschong R., Plaugher G., et al. Chiropractic management of a patient with subluxations, low back pain and epileptic seizures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21(6):410-418.

164 Elster E.L. Treatment of bipolar, seizure and sleep disorders and migraine headaches utilizing a chiropractic technique. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(3):E5.

165 Kumar A.R., Kurup P.A. Changes in the isoprenoid pathway with transcendental meditation and Reiki healing practices in seizure disorder. Neurol India. 2003;51:211-214.

166 Carpio A., Bharucha N.E., Jallon P., et al. Mortality of epilepsy in developing countries. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 11):28-32.

167 Epilepsy. Control, Centre for Disease. Online. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/basics/faqs.htm (accessed May 2009).

168 Ricotti V., Delanty N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6(4):347-353.