Chapter 5 Epidural Blocks

Epidural nerve block consists of the administration of small volumes of target-specific local anesthetics, corticosteroids, and other agents into the epidural space to interrupt the pain spasm cycle and reduce inflammation of either axial or radicular pain (Boxes 5.1 and 5.2; Table 5.1) [1,2]. These agents are injected through one of three approaches—interlaminar (for cervical, thoracic, and lumbar epidural injections), transforaminal (for cervical, thoracic, and lumbosacral injections), or caudal. The transforaminal block is discussed in Chapter 6.

BOX 5.1 The Concept of Epidural Injections

Approaches: interlaminar, transforaminal, caudal

Target structure: epidural space, especially the ventrolateral area

Local anesthetics, which interrupt both the pain spasm cycle and reverberating nociceptor transmission

Local anesthetics, which interrupt both the pain spasm cycle and reverberating nociceptor transmissionBOX 5.2 Mechanisms of Action of Glucocorticoids that Decrease Inflammation

Modified from Manchikanti L: Role of neuraxial steroids in interventional pain management. Pain Physician 2002;5:182-199.

Table 5.1 Postulated Mechanisms of Neural Blockade and Corticosteroids

| Postulated mechanisms of neural blockade | |

| Postulated mechanisms of corticosteroids |

Neural blockade alters or interrupts the following (see Table 5.1):

Neural blockade may be achieved with local anesthetics or corticosteroids (see Table 5.1). Local anesthetics interrupt the pain spasm cycle and transmission by reverberating nociceptors. Corticosteroids reduce inflammation by (1) inhibiting the synthesis or release of a number of pro-inflammatory substances or (2) causing a reversible local anesthetic effect.

The various modes of action of corticosteroids are as follows (see Table 5.1):

Temporary abolition of spontaneous ectopic discharges, resulting in suppression of dynamically maintained central hyperexcitability, as well as reinforcement of endogenous G-protein-couple receptor inhibition of N-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels

Temporary abolition of spontaneous ectopic discharges, resulting in suppression of dynamically maintained central hyperexcitability, as well as reinforcement of endogenous G-protein-couple receptor inhibition of N-type voltage-sensitive calcium channelsThe presumed effect of steroids is to reduce:

The mechanism of radiculopathy–neuropathic pain and the action of epidural steroid injection

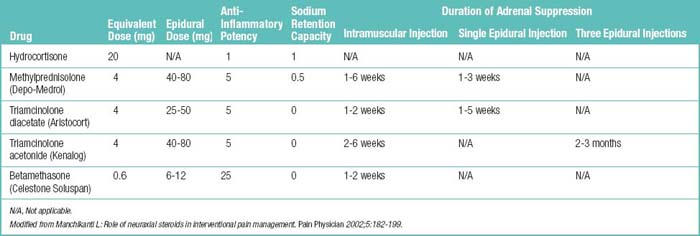

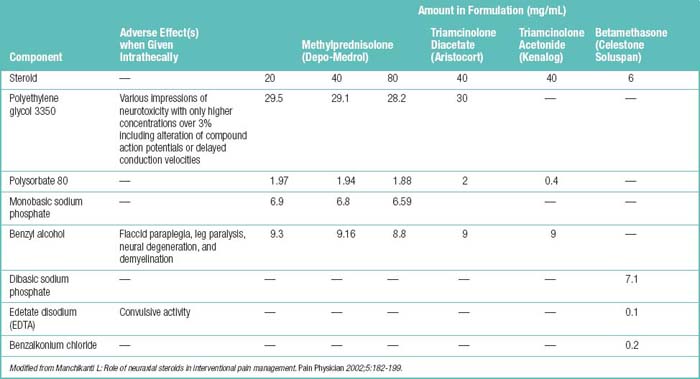

The rupture of the anulus fibrosus causes radiculitis either by mechanical pressure from disc protrusion or by chemical irritation of the nerve root by leaking material from nucleus pulposus (phospholipase A2) resulting in radiculopathy-neuropathic pain. In a neuropathic pain state, the steroids can decrease the conduction in injured nerves. It also has been observed that steroids can reduce the bulk of a scar by diminishing its hyaline portion, while leaving the fibrous skeleton intact. Tables 5.2 and 5.3 list profiles of, formulations for, and adverse effects of the commonly used epidural steroids.

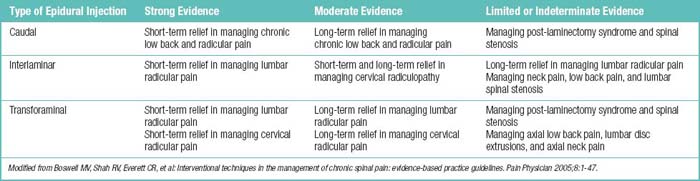

As already mentioned, the three main approaches for epidural steroid injection (ESI) are transforaminal, the most specific and effective route; interlaminar, via a midline or paramedian approach; and caudal (see Box 5.1).

The potential uses of fluoroscopically guided transforaminal ESIs include:

Management of acute, subacute, or chronic axial spine or radicular pain that is refractory to more conservative care such as rest, analgesics, and physical therapy

Management of acute, subacute, or chronic axial spine or radicular pain that is refractory to more conservative care such as rest, analgesics, and physical therapyEfficacy of the treatment/procedure is signified by the following:

Possible problems with epidural blockade

The injection variables that can affect target site concentration are as follows:

Recommendations for use

The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians makes the following recommendations:

Injections should be given at intervals of 2 weeks only as necessary according to medical necessity criteria.

Injections should be given at intervals of 2 weeks only as necessary according to medical necessity criteria.A definite trend toward nonsurgical management of lumbosacral disc herniation with radicular symptoms has been noted. [3] This change is appropriate for the following reasons:

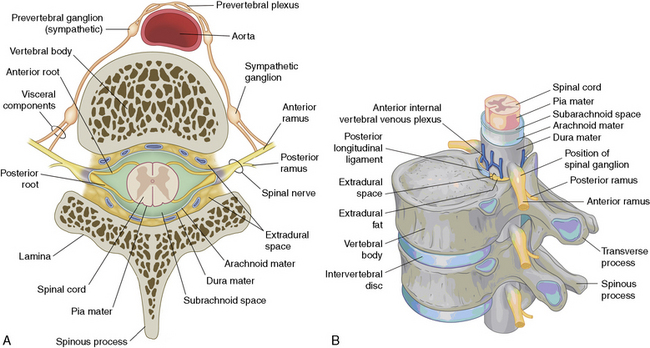

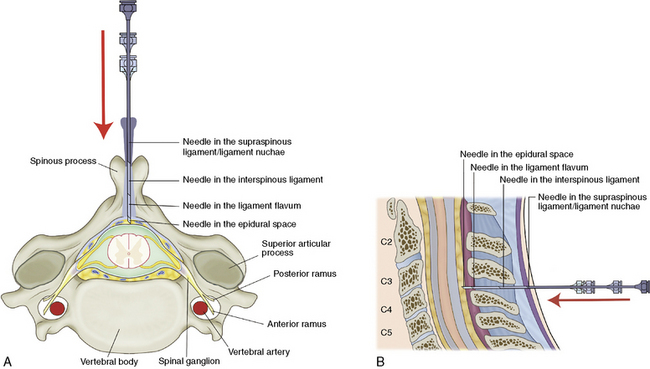

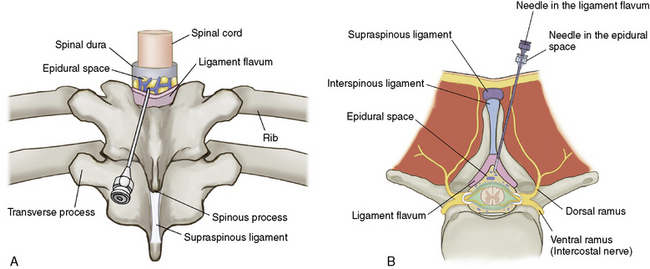

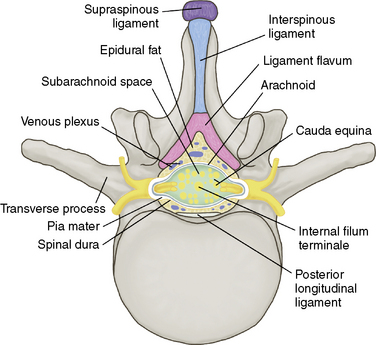

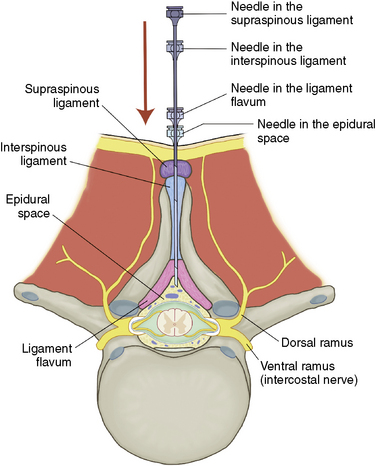

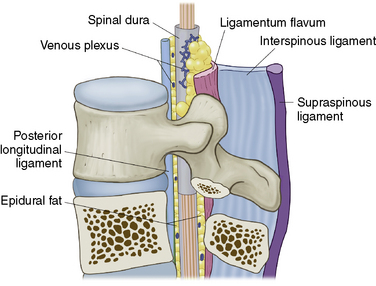

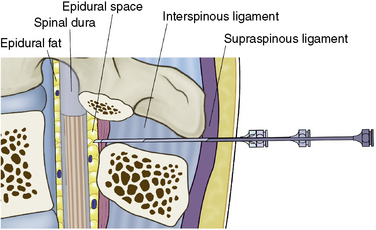

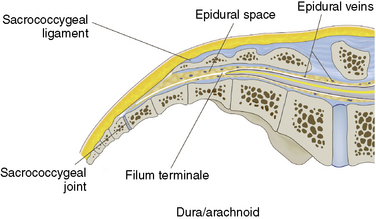

The contents of the epidural space

The contents of the epidural space are fat, epidural veins and arteries, and lymphatics (Fig. 5-1).

A shock absorber for thee other contents of the epidural space and the dura contents of the dural sac.

A shock absorber for thee other contents of the epidural space and the dura contents of the dural sac.Structures encountered during midline insertion of a needle into the lumbar epidural space

Complications

Complications related to needle placement and drug administration are as follows [4]:

Dural puncture, subdural injection, intravascular injection, spinal cord trauma, intracranial air injection, nerve damage, pneumothorax, vascular injury

Dural puncture, subdural injection, intravascular injection, spinal cord trauma, intracranial air injection, nerve damage, pneumothorax, vascular injury Infection, abscess formation, hematoma formation, epidural lipomatosis, cerebral vascular or pulmonary embolus, headache, increased intracranial pressure, brain damage, death

Infection, abscess formation, hematoma formation, epidural lipomatosis, cerebral vascular or pulmonary embolus, headache, increased intracranial pressure, brain damage, deathTable 5.5 Potential Side Effects or Complications of Epidural Steroid Administration

| Endocrine | Adrenal suppression, hypercorticism, cushingoid syndrome, hyperglycemia, precipitation of diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, hypokalemia, amenorrhea, menstrual disturbances, retardation of growth |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension, fluid retention, congestive heart failure, deep vein thrombosis |

| Musculoskeletal | Osteopenia/osteoporosis, avascular necrosis of bone, pathologic fracture, muscle wasting and atrophy, muscle pain, joint pain |

| Psychological | Mood swings, insomnia, psychosis, anxiety, euphoria, depression |

| Gastrointestinal | Ulcerative esophagitis, hyperacidity, peptic ulceration, gastric hemorrhage, diarrhea, constipation |

| Ocular | Retinal hemorrhage, posterior subscapular cataracts, increased intraocular pressure, exophthalmos, glaucoma, damage to optic nerve, secondary fungal and viral infections |

| Dermatologic | Facial flushing, impaired wound healing, hirsutism, petechiae, ecchymosis, hives, dermatitis, hyper/hypopigmentation, cutaneous atrophy, sterile abscess |

| Metabolic | Hyperglycemia, glycosuria, redistribution of fat, negative nitrogen balance, sodium and water retention |

| Nervous system | Headache, vertigo, insomnia, restlessness, increased motor activity, ischemic neuropathy, seizures |

| Other adverse effects | Epidural lipomatosis, fever |

Table 5.6 Characteristics of Adrenal Insufficiency (AI)

| Type | Cause(s) | Endocrinologic Features |

|---|---|---|

| Tertiary (most common form) | Usually from iatrogenic corticosteroid therapy and suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis | Hypothalamic/pituitary suppression or absence |

| Secondary (uncommon) | Decrease or absence of ACTH (may be panhypopituitary or anterior pituitary dysfunction) | ACTH-dependent AI |

| Pituitary depression, dysfunction/damage | Signs and symptoms usually due to loss of glucocorticoid function | |

| Tumor | Mineralocorticoid function usually intact | |

| Postpartum | Renal hypovolemia, more commonly hypoglycemia | |

| Primary (rare) | Autoimmune (70%-90%) | ACTH-independent AI |

| Infection | Increased ACTH production | |

| Inflammation | Possible hyperpigmentation | |

| Cancer (breast, lung, melanoma) | ||

| Acute addisonian crisis |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Preoperative preparation

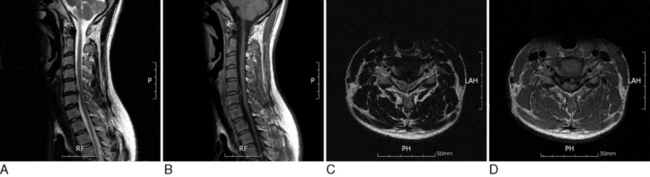

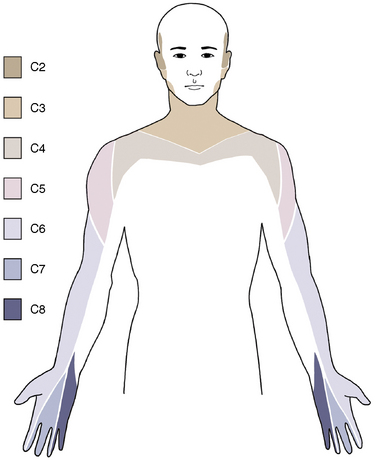

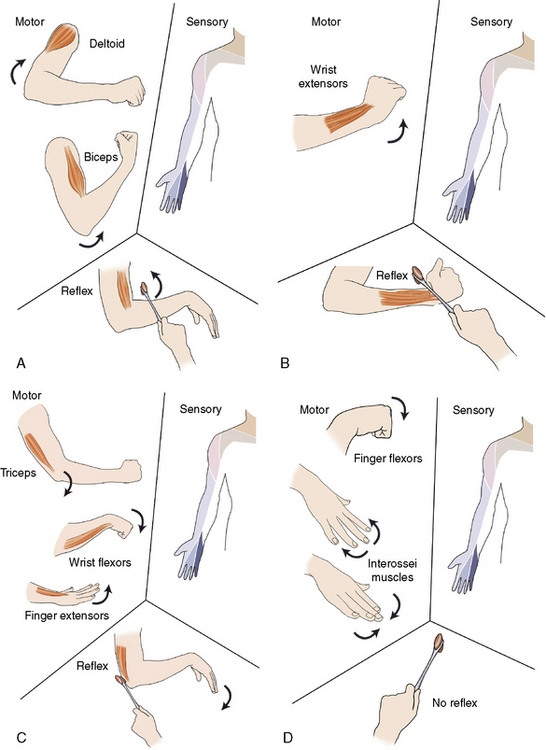

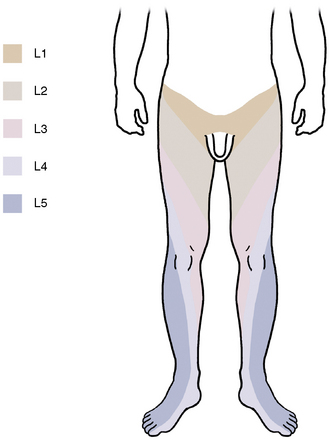

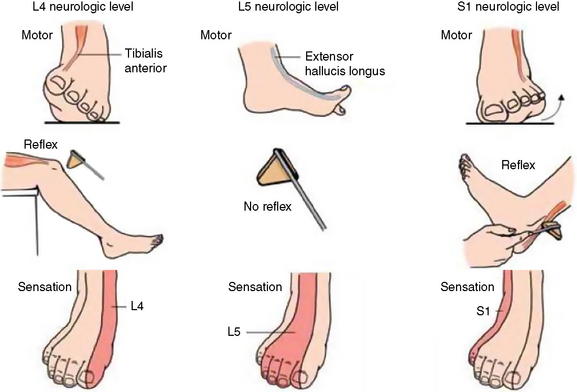

The patients who are suffering from axial pain on the spine and radicular pain on extremities according to the dermatome are candidates for epidural nerve block (Figs. 5-2 to 5-5).

Figure 5–2 Cervical dermatome chart.

(From Waldman SD. Physical Diagnosis of Pain: An Atlas of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2006, pp 20-33.)

Figure 5–3 (A) C5, (B) C6, (C) C7, and (D) C8 dermatome distribution.

(From Waldman SD: Physical Diagnosis of Pain: An Atlas of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2006, pp 20-33.)

Figure 5–4 Lumbar dermatomal chart.

(From Waldman SD: Physical Diagnosis of Pain: An Atlas of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2006, pp 235-42.)

Figure 5–5 L4, L5, and S1 dermatome distribution.

(From Waldman SD: Physical Diagnosis of Pain: An Atlas of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2006, pp 235-42.)

Physical Examination

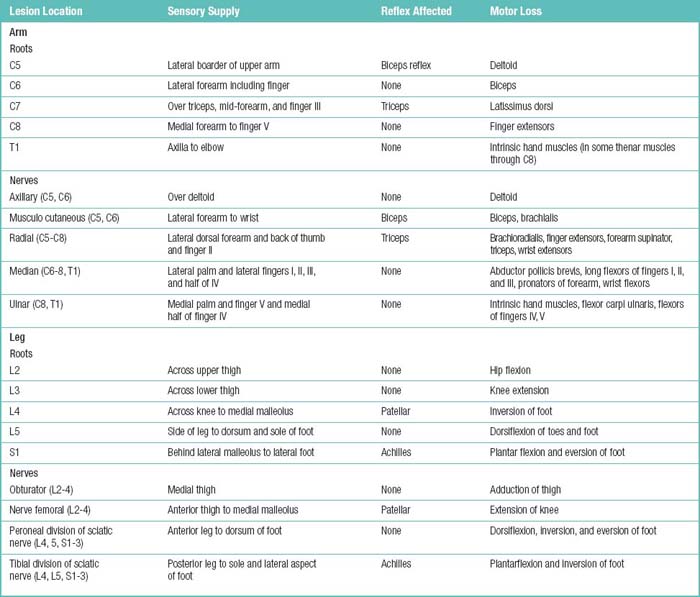

Table 5.8 The Important Muscle Groups and Motions Associated with Cervical and Lumbar Myotomes

| Root | Muscle Group(s) and Motion(s) |

|---|---|

| C5 | Elbow flexors, shoulder abductors and external rotators |

| C6 | Elbow flexors, wrist extensors and pronators, shoulder external rotators |

| C7 | Elbow extensors, wrist pronators |

| C8 | Extension of index finger, finger abduction and flexion, abduction of thumb, wrist flexion |

| T1 | Finger abduction |

| L2 | Hip flexion |

| L3 | Hip flexion, hip adduction, knee extension |

| L4 | Knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion |

| L5 | Ankle dorsiflexion, great toe extension, ankle eversion, hip abduction and internal rotation |

| S1 | Ankle plantarflexion |

Table 5.9 Five-Point Scale for Grading of Muscle Strength

| Grade | % | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 100 | Active movement against full resistance (normal strength) |

| 4 | 75 | Active movement against gravity and some resistance |

| 3 | 50 | Active movement against gravity |

| 2 | 25 | Active movement with gravity eliminated |

| 1 | 10 | Trace movement or barely detectable contraction |

| 0 | 0 | No muscular contraction identified |

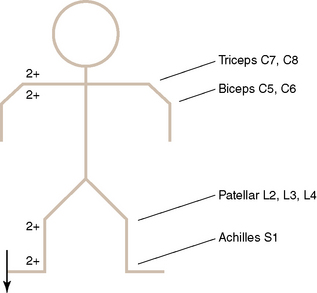

Table 5.10 Deep Tendon Reflexes and Their Roots

| Reflex | Root(s) |

|---|---|

| Biceps | C5, C6 |

| Brachioradialis | C5, C6 |

| Triceps | C6, C7 |

| Patellar tendon | L2, L3, L4 |

| Medial hamstring | L5, S1 |

| Ankle jerk (Achilles tendon) | S1 |

Table 5.11 Scale for Grading Deep Tendon Reflex Responses

| Grade | Response |

|---|---|

| 0+ | None |

| 1+ | Sluggish |

| 2+ | Active or normal |

| 3+ | More brisk than expected, slightly hyperactive |

| 4+ | Abnormally hyperactive, with intermittent clonus |

Instrumentation

Equipment needed for an epidural nerve block is as follows:

Two different lengths (6 or 10 cm) of 23 gauge epidural needles are used depending on the location of insertion

Two different lengths (6 or 10 cm) of 23 gauge epidural needles are used depending on the location of insertion 2- or 5-mL well-lubricated sterile glass syringe for testing of epidural space using the loss-of-resistance or hanging-drop method

2- or 5-mL well-lubricated sterile glass syringe for testing of epidural space using the loss-of-resistance or hanging-drop methodProcedures

The procedures for epidural blocks are described here [5–7].

Cervical and Thoracic Epidural Block through the Interlaminar Midline Approach without Fluoroscopic Guidance

Thoracic Epidural Block through the Interlaminar Paramedian Approach without Fluoroscopic Guidance

Figure 5-9 illustrates a thoracic epidural block using an interlaminar paramedian approach.

Lumbar Epidural Block through the Interlaminar Midline Approach without Fluoroscopic Guidance

Figures 5-10 to 5-13 illustrate a lumbar epidural block using the interlaminar midlline approach.

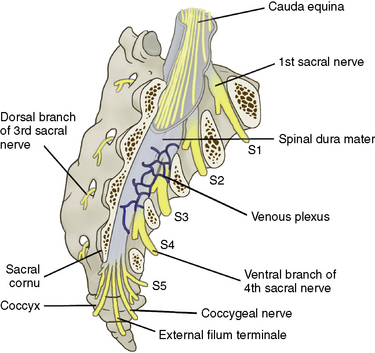

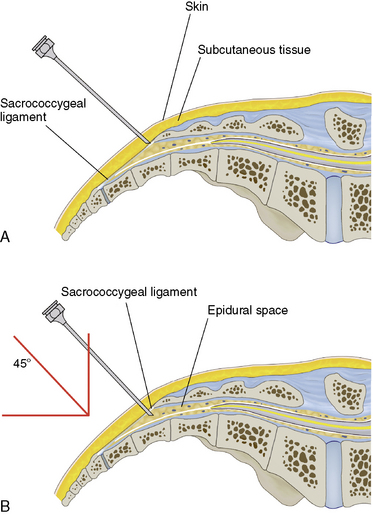

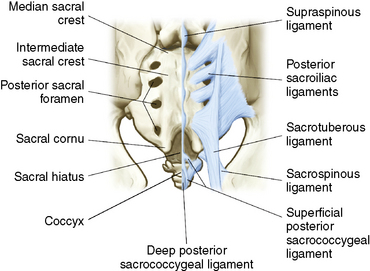

Caudal Epidural Block with Patient in the Prone Position

Figures 5-14 to 5-17 illustrate the following procedure for a caudal epidural block with the patient in the prone position

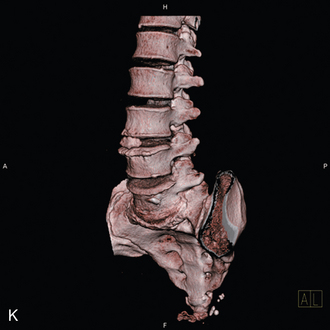

Figure 5–14 The triangular sacrum consists of the five fused sacral vertebrae, which are dorsally convex.

Caveats

The following issues should be kept in mind during an epidural block:

1 Abdi S., Datta S., Lucas L.F. Role of epidural steroids in the management of chronic spinal pain: A systematic review of effectiveness and complications. Pain Physician. 2005;8:127-143.

2 Manchikanti L. Role of neuraxial steroids in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2002;5:182-199.

3 Weinstein S.M., Herring S.A. Lumbar epidural steroid injections. Spine J. 2003;3:37S-44S.

4 Boswell M.V., Shah R.V., Everett C.R., et al. Interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain: Evidence-based practice guidelines. Pain Physician. 2005;8:1-47.

5 Waldman S.D. Atlas of Interventional Pain Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998;121-127.

6 Waldman S.D. Atlas of Interventional Pain Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998;199-204.

7 Waldman S.D. Atlas of Interventional Pain Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998;205-211.

8 Waldman S.D. Physical Diagnosis of Pain: An Atlas of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2006;308-317.

9 Waldman S.D. Physical Diagnosis of Pain: An Atlas of Signs and Symptoms. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2006;337-350.