CHAPTER 127 Epidemiology of Injuries

INTRODUCTION

Back pain is one of the most common reasons patients seek medical care. Low back pain is the second leading cause for primary care office visits, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 60–90% and an annual incidence of 2–5%.1,2 In the general population, back pain is the number one cause of disability in patients younger than 45 years of age, and the number three cause for those older than age 45. Although there has been recent debate as to whether athletes are protected from back pain or more susceptible to back pain, it remains a common complaint in the athletic population. Back pain etiology in the athlete varies from mild lumbar muscle strain to traumatic fracture dislocation of the cervical spine with associated cord compromise. However, the most common etiology of athletic back injury mirrors that of the general population – injury to soft tissue structures including muscle, ligaments/capsule, and fascia. Past studies have reported the inability to identify a specific pain generator in up to 85% of cases of low back pain. Despite these historical findings, correct identification and treatment of biomechanical deficits leading to back pain can prevent injury from recurring and progressing to a chronic phase. From a radiographic standpoint, degenerative disc disease and spondylolysis are the most commonly associated structural abnormalities seen in athletes. In fact, numerous studies have shown an increased prevalence for degenerative spine changes in athletes when compared to nonathletes.3,4

GENERAL ETIOLOGIC FACTORS

The degenerative cascade model as an etiologic predictor of back pain

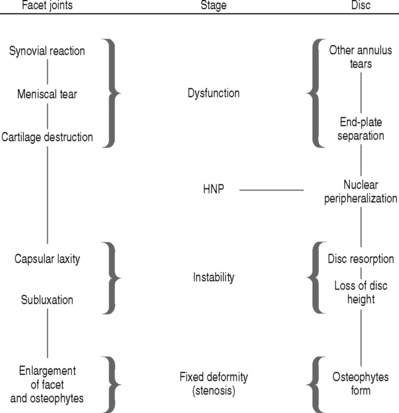

Virtually all athletes are subjected to repetitive end range forces on the spine, grueling competitive schedules, rigorous training routines and, depending on the sport, significant contact forces with other players. The result is an accelerated progression through the degenerative cascade of spinal motion segments. The degenerative cascade model based upon the work of Kirkaldy-Willis5a is currently a comprehensive model of back pain (Fig. 127.1). It describes three basic stages of degeneration found in spinal motion segments due to the effects of trauma and repetitive stress. At each stage, the classification system outlines the pathoanatomical and pathophysiologic changes that occur throughout the motion segment, which can be used to predict etiology of spine-related pain. It is an important process to understand when examining etiology and epidemiology of back pain in athletes.

Fig. 127.1 Overview of the degenerative cascade.

(Adapted from Selby D, Saal JS: Degenerative Series. CAMP Healthcare, with permission.5)

A basic overview of the degenerative cascade is as follows:

THE EFFECT OF AGE ON ETIOLOGIC DISTRIBUTION OF BACK PAIN

Pediatric and adolescent athletes

Back pain and back injury occurs in 10–15% of all young athletes.6 The prevalence of specific injury types is related to sport played as well as position within that sport. When compared to their adult counterparts, pediatric and adolescent populations have fewer secondary gain issues and are more likely to have a pathologic etiology for their pain. Therefore, a high index of suspicion and a low threshold for the utilization of diagnostic imaging and evaluation techniques should be applied to this population.7 Red flag signs and symptoms such as night pain, constitutional symptoms, non-specific onset, failure of pain remittance with rest, weight change, skin rash, and multiple joint or organ involvement should prompt further investigation and appropriate referral. This young population also deserves special attention because some causes of back pain may be related to the growth process itself. The distribution of spine-related causes for back pain in sports can be organized by anterior element, posterior element, and soft tissue etiologies.

Anterior element

Disc disease accounts for 10% of back pain in athletes under the age of 21, and 2% of all disc herniations are attributable to this age population. The most commonly involved sports include: weight lifting, rowing, football, and wrestling.8 Scheuermann’s disease, a progressive thoracic kyphosis due to anterior wedging of at least 5° in three or more consecutive vertebral bodies, occurs in 0.4–8.3% of the population. The most common age group is 13–17 years, and increased prevalence has been noted in sports such as waterskiing.9 Thoracolumbar Scheuermann’s has been reported in weightlifting, football, gymnastics, and wrestling.10,11 Infection presenting as idiopathic infectious discitis is more common in younger patients with an average age of 6 years; however, reports span the entire pediatric and adolescent age group. Vertebral osteomyelitis, benign and malignant tumors, scoliosis, and rheumatologic disease are also more prevalent in this younger population than in adults.

Posterior element

Posterior element injuries are more common in sports requiring repetitive hyperextension such as gymnastics, football, figure skating, diving, and dance.4,6,12 Spondylolysis has been reported to account for up to 47% of low back pain in adolescent athletes.13 Spondylolisthesis is usually associated with a pars interarticularis defect or elongation, and most slip progression tends to occur during the growth spurt in preadolescence.6,14 Incidence is reported from 11% in gymnastics to 63% in diving.15,16 Lumbar facet syndrome (Z-joint synovitis) is also reported in this population, and is associated with the first stage of the degenerative cascade.

Spinal cord injury

It is noteworthy to mention the high risk of cervical spine injury in the pediatric population associated with trampoline use and diving accidents. In 1998, more than 6500 trampoline-associated cervical spine injuries occurred in pediatric patients. Although most were minor injuries, there were reports of death and quadriplegia. This represented a fivefold increase over a 10-year period at the time of report.17 Increased risk for serious spinal trauma due to diving in uncontrolled environments is also prevalent in this population.

Young adult athlete

The repetitive multiplanar nature of sport-specific training regimens (rotation, flexion–extension, and axial loading of the spine), high number of hours spent in training, and the general use of weight training for overall strength and conditioning may lead to earlier evidence of stage I (dysfunction) and stage II (instability) degenerative change in the spine compared to nonathletes. This is supported by radiographic evidence as well as the types of injury commonly encountered in this population.3,4

Older adult athlete

As the general population ages, the number and age of those participating in sporting activities continues to increase. There will be approximately 70 million people age 65 or older in the United States by the year 2030.18 The spinal motion segments in this subset of the population are more likely to be further along in the degenerative cascade (instability and stabilization phases of degeneration). In addition, medical comorbidity and age-related changes including diminished bone density, general loss of strength and muscle mass, changes to the vestibular, visual, and somatosensory systems, as well as decreased joint flexibility may play a role in back injury.19

EPIDEMIOLOGIC DATA AND BIOMECHANICAL FACTORS FOR SELECTED SPORTS

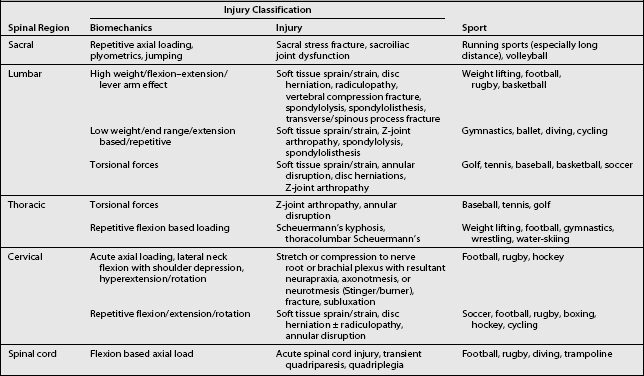

Table 127.1 summarizes the basic biomechanical etiologic factors associated with common spine injuries in sports.

Baseball/softball

Overview

Between 1995 and 1999, back injuries accounted for approximately 5% of all disabled list (DL) days in major league baseball. Overall, back pain accounted for the fifth highest number of injuries per anatomic region reported. In 1999, the number of DL days attributable to back injury reached 1490 days, which even outnumbered the 1348 days for wrist and hand injury.20

Severe injury to the cervical spine, while uncommon, is typically associated with head-first sliding. These neck hyperextension injuries range from ligamentous disruption to vertebral fracture and quadriplegia. The mechanism involves rapid deceleration against a stationary base or opposing player. However, the incidence of cervical spine injury has decreased since the advent and widespread use of breakaway bases.21 Other cervical spine injuries, which may be observed in pitchers, include those to the Z-joints and cervical discs.

Lumbar spine injury in baseball and softball is commonly attributed to hitting. Frequent participation in batting practice produces repetitive rotational movement that accelerates the progression of degenerative changes in spinal motion segments. The most common etiology of pain in this population is soft tissue in nature, while less common injuries include disc herniation, Z-joint arthropathy, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis.22,23

Fast-pitch softball

According to the NCAA Injury Surveillance System data from 1997/1998, 5–15% of all traumas in fast-pitch softball were due to injury to the thoracic, back, and abdominal regions. Low back injury accounted for 7% of these injuries. Back injury is most commonly associated with overuse injuries and contusions.24

Functional considerations

Frequent batting practice subjects the lumbar spine to repetitive stress injury. Watkins recorded surface EMG data from 18 professional baseball players to evaluate hitting mechanics and determined that the erector spinae and abdominal oblique were the most important muscles involved in trunk stabilization and rotation for smooth power transfer throughout the kinetic chain. They also noted that hamstring and lower gluteus maximus contributed most to the ‘stable base’ and ‘power-of-the-thrust’ form that the torso ‘uncoils’ during the swing.22 As predicted by the kinetic chain model of biomechanics, coordinated transfer of muscle activity occurs from the lower extremities to the trunk to the upper extremities. Any isolated weakness along the kinetic chain places undue stress on isolated functional segments and may eventually lead to overuse injury.

Kinetic chain dysfunction is also observed in injuries sustained by pitching. According to Casazza and Rossner, the baseball pitch may be the most dynamic motion executed in sports. Acceleration of the upper extremity is driven by an initial anteroposteriorly directed ground force that is transformed into a rotational force at the hip that continues through the spine to the shoulder, culminating in forceful internal rotation to accelerate the arm. The spine also plays a crucial role in the attenuation of forces during the deceleration phase of throwing. Overload of the Z-joints and the intervertebral discs may occur if the thoracolumbar fascia is unable to dissipate the forces from the spinal motion segments.25 Restricted or excessive range of motion and poor coordination at specific segments along the chain may be as important, or more important, than relative weakness of isolated segmental musculature.

Basketball

Overview

In basketball players, thoracic and lumbar spine injuries are more common than those to the cervical spine. Overall, the most common injuries to the spine are lumbosacral soft tissue strains and sprains, as opposed to discogenic or bony abnormalities. Traditional ‘weekend warrior’ athletic injuries commonly arise as a consequence of diminished physical condition combined with participation in intensely competitive pick-up games. These injuries are usually soft tissue in nature; however, a predisposing spinal abnormality such as degenerative disc disease or spondylolisthesis may complicate the diagnostic picture. Competitive athletes at the high school, college, and professional levels are usually well conditioned but may ignore core strengthening and therefore also tend to suffer from soft tissue injuries to the low back.26

Meeuwisse et al. analyzed collegiate varsity basketball injuries as reported through the Canadian Intercollegiate Sports Injury Registry (CISIR) over a 2-year period. A total of 215 injuries accounted for 1508 sessions of time loss. Injury to the lumbar spine and pelvis accounted for 4.7% of injuries with 50.5 total sessions lost and average time loss of 5.05 days per injury. Injury to the thoracic spine and ribs accounted for only 1.9% of injuries with 7 total sessions lost and an average time loss of 1.75 days per injury.27 Other studies have reported a higher incidence of lumbar/hip-directed injuries. Hickey et al. reviewed injuries among female basketball players at the Australian Institute of Sport. Of the 49 elite female players followed, a total of 223 injuries over the time period of 1990 to 1995 were reported. Injury to the lumbar spine was the third most frequently injured region of the body with an incidence of 11.7%, with the most frequent diagnosis being mechanical low back pain (4.5%).28 Henry et al.28a retrospectively reviewed injuries in professional men’s basketball players over a period of 7 years, and found that back and hip injuries accounted for 11.5% of all injuries. The majority of these injuries were diagnosed as contusions. Only 1% of injuries occurred to the neck, and all were described as contusions or strained muscles.

Although less common, discogenic injury, spondylolisthesis, and fractures of the spine have been reported in basketball players. Fracture types include vertebral body compression, spondylolysis, spinous process fractures, and transverse process fractures. The prevalence of spondylolysis is reported to be as high as 9%.26,29,30

Functional considerations

Discogenic back pain may present as localized pain occurring in the dysfunction and instability phases. Nerve root irritation may eventually arise in the stabilization phase of the degenerative cascade. Spinal stenosis may occur more frequently in taller athletes than in the general population26 and may play a contributing factor. Older players with existing degenerative disc disease presenting in the stabilization phase may develop nerve root irritation and radicular symptoms.

Common fractures at the lumbar spine include transverse and spinous process, pars interarticularis, and vertebral endplate. Vertebral body compression fractures are rare in basketball, but may occur due to supramaximal axial loading of the spine.26 Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and pars interarticularis injury represent a spectrum of pathologic dysfunction as described by the degenerative cascade. High-grade spondylolisthesis is rare in high-level athletes. Low-grade spondylolisthesis can occur as a consequence of pars stress fracture, which is usually isthmic in origin, but may also be traumatic or rarely pathologic in nature. These injuries are frequently accompanied by lumbar spine pain and associated with tight hamstrings and the functional adaptation complex of loss of the lumbar lordosis. Degenerative forms of this injury are more common in women and elderly populations. Slip rarely progresses beyond 33%.31

Diving

Overview

Recreational diving accidents are the fourth most common cause of spinal cord injury following motor vehicle accidents, gunshot wounds, and falls. They have caused more cases of quadriplegia than all other sports combined.32,33 In comparison, there are only two reports of fatalities in international competition in the literature, both of which occurred during platform diving. In the United States, there has been no reported fatality or catastrophic injury during supervised training or competition in over 80 years. Factors related to catastrophic injury in diving include lack of formal training, insufficient water depth, lack of supervision, and alcohol consumption.

Cervical strains and sprains, as well as brachial plexus stretch injuries can occur but are thought to be uncommon due to the protective effect of arm position during entry to the water.34 Low back pain is common in competitive divers, and in many cases may be related to spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, or Z-joint arthropathy. Rossi performed a radiographic study of 1430 athletes, including 30 divers, and found a 63% incidence of spondylolysis in divers compared to an overall incidence of 16.7% for all athletes. This was the highest incidence of all sports in the study.16 Within the sport of diving, a higher incidence of lumbar spondylosis has been noted in platform diving when compared to springboard diving.35

Football

Overview

Football is a violent, high-contact sport. Injuries to the spine account for approximately 40% of all traumatic injuries reported. Cervical spine injuries account for approximately 7–8% of all injuries to high school football players.36 Compared to other sports, football and rugby have the highest rate of cervical spine-related injury. These injuries range from transient cord neurapraxia to cervical spine fracture resulting in permanent quadriplegia. The significant amount of traumatic injury in football results from the unexpected deforming loads that occur during high-velocity collisions between players, frequently with the use of the helmet and head for spearing, tackling, and blocking.37 Major etiologic factors for low back injury in football include the heavy focus on weight training and strength development, as well as repetitive, intense player-to-player contact during game play and practice drills.

Cervical spine

Hagel et al. evaluated rates of acute injury among football players in the Canada West Universities Athletic Association over the time period of 1993–1997. The incidence of head and neck injuries was found to be 1.59 injuries and 15.06 injuries per 1000 athletic exposures for practice and game play, respectively.38

While cervical spine trauma is rare, injuries that occur can be devastating. Reports from the National Football Head and Neck Injury Registry (NFHNIR) from 1971 to 1988 revealed the following distribution of midcervical spine injury. At the C3–4 level, there were four intervertebral disc herniations, four anterior subluxations of C3 upon C4, six unilateral articular process dislocations, seven bilateral articular process dislocations, and four fractures of the C4 vertebrae.39,40 In addition, flexion teardrop fractures have also been reported in football players. These rare injuries may or may not be associated with neurologic sequelae.

‘Stingers’ or ‘burners’ are common clinical entities that occur in high-contact sports such as football, rugby, and hockey. They represent a spectrum of nerve injury severity as described by Seddon: neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Cervical cord neurapraxia has an estimated prevalence of seven injuries per 10 000 participants.41 Clinical manifestations include transient loss of function, burning, and lancinating pain in the trapezius and shoulder regions extending down the arm in a dermatomal distribution. Symptoms typically last up to 10–15 minutes, and some trace neurologic deficit may last for months. More detailed information on sports-related cervical spine injuries can be found in Chapter 126.

Lumbar spine

Mechanical low back pain is common in football players. A high incidence is reported at the beginning of training camp, and is most notable in offensive linemen in conjunction with blocking drills. Repetitive forced extension of the lumbar spine may lead to Z-joint pain, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis.42,43 The reported incidence of spondylolysis in football players varies greatly, and has been reported to be as high as 50%.44 McCarroll et al. followed 145 freshman football players through their careers at Indiana University from 1978 to 1983 and reported the overall incidence of spondylolysis to be 15.2%, with 2.4% acquiring the diagnosis during the study period. The incidence of spondylolisthesis in this group was 4%. Of 31 players presenting with low back pain during the study period, 42% had radiographic findings of spodylolysis.45 A study by Shaffer et a.l46 examined, via physician survey, the prevalence of known isthmic spondylolisthesis in elite football players. Interviewing the team physicians of all 28 NFL teams and the top 25 NCAA teams as determined at the end of the 1993–1994 season, they found that 21 NCAA players and 20 NFL players were reported as known to have spondylolisthesis. This accounts for an estimated prevalence of 0.9% for NCAA players, and 1.5% for NFL players. Approximately half of the affected players were linemen (48% of NCAA and 50% of NFL). The most common level affected was L5–S1 (76%), and of all known cases 86% of NCAA and 75% of NFL were grade I slips. Six players in total had grade II slips, and two players had grade III slips. Other authors have reported the incidence of spondylolisthesis to be as high as 21%.47 These reports are contrasted with a 3–6% incidence of spondylolysis and 2–7.7% incidence of spondylolisthesis in the general population.46,48 However, these prevalence rates by Shaffer et al. are likely to be artificially low, as this report only included athletes with known spondylolisthesis and did not utilize evaluation of diagnostic imaging procedures.

Other lumbar injuries include acute transverse process and spinous process fractures, disc injuries, radiculopathy, and tears in the thoracodorsal and lumbodorsal fascia. Tewes et al.49 reviewed all lumbar transverse process fractures that were known to have occurred in the NFL during the period of 1983 to 1991. Of the 29 cases, 27 were attributed to impact-related injuries, while two cases were thought to be secondary to a torsional mechanism. The fractures were fairly well distributed in regard to position played. Football players also have an increased incidence of lumbar degenerative disc disease. Studies have shown that weight training and hyperextension play a significant role in the production of intervertebral disc injury and degenerative disease in football players.50–52

Functional considerations

Axial loading of the cervical spine is the primary mechanism of injury to the cervical spine in football. On analysis of videotape of actual injuries causing permanent quadriplegia, Torg et al. found that axial loading was the mechanism in every case.53

When the cervical spine undertakes a compressive force in its neutral position of lordosis, the forces are dissipated by the cervical paravertebral musculature, ligaments, and intervertebral discs. When the neck is flexed to 30°, the cervical spine becomes straight and the forces created by an axial load are no longer dissipated by the supporting soft tissue structures. The spine becomes compressed by the decelerated head and the accelerating trunk. The end result of this structural failure may be fracture, subluxation, or Z-joint dislocation. This compressive deformation leading to failure may occur in as little as 8.4 msec.54

Stingers or burners are typically the result of one of four major etiologic mechanisms causing stretch or compression of a nerve root or plexus. These mechanisms include (1) pure axial compression, (2) contralateral lateral neck flexion with ipsilateral shoulder depression, (3) hyperextension with ipsilateral side-bending of the cervical spine, and (4) a direct blow to the brachial plexus at Erb’s point (located in the supraclavicular region). Axial loads may cause unilateral arm pain, bilateral arm pain, or even transient quadriparesis secondary to cervical stenosis. Contralateral neck flexion coupled with ipsilateral shoulder depression injury may result in longer-lasting pain and dense paresthesia secondary to brachial plexus traction injury. Hyperextension with ipsilateral side-bending injuries usually result in radicular pain in dermatomal pattern secondary to functional narrowing of the neural foramina.55,56

Lumbar injuries range from lumbodorsal fascia or muscle strain to spinous process fracture or disc pathology. Repetitive extension movements combined with blows to the lumbar spine, especially when in a position of sudden off-balance rotation, may contribute to pars injury, Z-joint pain, and spinous or transverse process injury. This mechanism also contributes to the degeneration of specific vertebral motion segments. Disc degeneration and spondylolysis is prevalent in offensive linemen due to the repetitive hyperextension combined with rotation under load as they block opposing players. Football linemen sustain an average peak compression force of 8679±1965 N at the L4–5 motion segment when hitting a blocking sled. The average peak and shear forces are 3304±1116 N and 1709±411 N, respectively. The magnitude of these forces generated during blocking drills is greater than that which was determined during fatigue studies to cause pathologic changes in the disc and pars interarticularis.43 Core strength for adequate lumbar stabilization becomes an essential component to injury prevention in these athletes.

Golf

Overview

Golfers have the highest incidence of back injury of all professional athletes.57 A recent study of 703 professional and amateur golfers58 found that back injuries were the first and second most common injuries, in the respective groups. Back pain accounted for 34.5% of all professional injuries and 24.7% of all amateur injury reports. The lumbar spine was most commonly affected (62%) followed by the cervical (33%) and thoracic (5%) regions. In 92% of reported back problems, excessive play was blamed, as opposed to single traumatic events. The considerable rotational and compressive forces to the spine imposed by the golf swing subject players to myofascial pain, lumbar disc disease, spondylolysis, Z-joint arthropathy,59 and vertebral compression fractures.60

Injuries to the thoracic and lumbar spine are associated with greater time loss than injuries to all other anatomic regions except the elbow. When examining available gender data, there is no significant difference between men and women for number, severity, or distribution of injury.58

Functional considerations

The repetitive nature of the sport lends itself to the development of degenerative changes in the spine. Studies have noted increased prevalence of injury when players hit more than 200 range balls or play four or more rounds per week.58 During the golf swing, the lumbar spine is subject to significant rotational and compressive forces. Many golfers use what is referred to as the ‘modern swing’ in which their hips slide from side to side, rather than rotating, to increase torque in the back and shoulders in attempt to increase angular club head speed. The endpoint of this swing positions the golfer in a reverse C stance that places the lumbar spine in extreme hyperextension. In attempt to hit the ball further, many players exaggerate this position, leading to increased force through the spine.

In order to decrease the forces acting on the spine, an ‘athletic swing’ (also termed ‘classic swing’) that utilizes the larger muscles of the lower extremity and trunk to dictate the swing is advocated. The athletic swing follows the principles of the kinetic chain to sequentially load and then unload each successive joint complex, with hip rotation coupled to that of the shoulders. The result is a more efficient swing with increased power and decreased rotational stress through the lumbar spinal motion segments. At the end of the swing, the player maintains a more upright posture.

Nonswing-related factors are also important in the development of back pain in golf. A statistically significant association between low back pain and range of motion deficits in lumbar spine extension, lead hip internal rotation, and lead hip FABER’s distance (knee to table distance with the subject supine and hip flexed, abducted, and externally rotated) has been documented in professional golfers.61 Golfers who carry their bag on a regular basis also have a significantly higher incidence of low back injury.58 It has been demonstrated that significant shrinkage and decreased shock absorbance of the intervertebral disc occurs after carrying a golf bag over a distance of only nine holes.62

Gymnastics

Overview

There is a high prevalence of low back pain in gymnasts. Review of the literature reveals a range 12–85% depending upon the study population and definition of injury.3,63–66 In women’s gymnastics, floor exercises account for the majority of injuries, followed by balance beam, uneven bars, and vaulting.67 While there is a wide variance of injury to the spine in gymnasts, soft tissue injury is the most common etiology of back pain, as it is in most sports.67,68 Symptoms include myofascial pain, tenderness to palpation, and range of motion limitations. Other important causes of back pain in gymnasts include muscle strains, ligament sprains, degenerative disc disease, disc herniations, Scheuermann’s disease, compression fractures, Schmorl’s nodes, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, Z-joint chondromalacia, and spinous or transverse process avulsion.

Spondylolysis is the classic spine-related injury associated with gymnastics. This is thought to be due to the repetitive hyperextension and rotational forces that gymnastic maneuvers place upon the lumbar spine. Compared to the estimated prevalence of 3–6% in the general population,48,69 the reported incidence of spondylolysis in gymnasts is significantly higher, ranging from 11% to 32%.9,16

While back pain in gymnasts is commonly associated with injury to the posterior elements, there is also a high incidence of anterior and middle column disease. A prospective study of spinal injury in 33 top level gymnasts by Goldstein et al.70 revealed MRI evidence of disc abnormality in 24%. In the 12 athletes with MRI-documented degenerative lumbar spine changes, there was a trend of increased degenerative change with increased skill level. The distribution of degenerative change was 1 of 11 pre-elite, 6 of 14 elite, and 5 of 8 Olympic-caliber gymnasts. Also noted in this series was a positive correlation of abnormal MRI findings with the average number of training hours per week and the age of the gymnast.

As witnessed in the study by Goldstein et al., gymnasts who train for more than 15 hours per week may be at risk for accelerated degenerative changes of the lumbar motion segments (adjacent vertebrae, intervening disc, paired Z-joints and capsules, ligamentous components, lateral neural foramina). Supporting this study is the work of Sward which evaluated 24 elite male gymnasts. He found a higher prevalence of disc degeneration in male gymnasts (75%) compared to nonathletes (31%).71 Jackson et al. state that the most limiting lumbar disc pathology in the gymnast involves posterior and posterolateral disc herniation with associated nerve root irritation or compression. In these cases, epidural corticosteroid injections have been shown to be helpful in 40% of athletes with more chronic radicular symptoms.72

Bony abnormalities such as compression fractures and Schmorl’s nodes are reported pain generators in gymnasts. Superior or inferior herniation of the nucleus pulposus through the growth plates of vertebral bodies, commonly referred to as a Schmorl’s node, may occur in skeletally immature gymnasts. These injuries have been linked to hyperflexion and are most commonly seen at the thoracolumbar junction.63,66,73

Functional considerations

The most frequently performed gymnastic skills include front and back walkovers, front and back handsprings, and the handspring vault. These maneuvers all require significant lumbar hyperextension for proper performance. This repetitive hyperextension, which is often coupled with torsional movement at end range of motion, results in repeated loading of the pars interarticularis and may eventually lead to spondylolysis. With continued stress, the associated spinal motion segments are placed at risk for spondylolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis occurs most frequently at the L5–S1 level. Developing adolescent gymnasts are at risk for both isthmic and traumatic subtypes of spondylolisthesis. From a clinical standpoint, these injuries are often associated with increased lumbar lordosis and tight hamstrings. When associated with nerve root irritation, patients may present with radicular pain. The problem of repetitive hyperextension movements has been recognized by the international governing body of rhythmic sportive gymnastics, The Federation International Gymnastics, and they have begun to limit the number of extension elements in a given routine to a single element.68

In addition to repetitive lumbar hyperextension, gymnasts also perform maneuvers producing repetitive torsion coupled with flexion. This may explain the cases of herniated nucleus pulposus reported in adolescents. These injuries most often occur at the L3–4 and L4–5 levels but have also been reported at the thoracolumbar junction.66,74 Improving range of motion at other sites along the kinetic chain, such as the hips and thoracic spine, may allow the athlete to achieve similar positions with less stress placed upon the extended lumbar spine.

Soccer

Overview

There are no comprehensive reviews in the literature dedicated to back injury in soccer. Soccer is a contact sport that involves high-speed collisions, dribbling, feigning, heading, throw-ins, and acrobatic movements in the air involving flexion, extension, and rotation of the trunk. Spinal injuries in soccer have been reported in both the cervical and lumbar regions. Trauma to the cervical spine has been reported as the sequelae of a bicycle kick. In 1978, a player of Nantes, France, landed on his occiput following a bicycle kick and sustained a bilateral fracture-dislocation of C5–6.75 Other acute cervical injuries reported in the literature include disc herniations.76

Lumbar spine injuries are the most common back injuries reported. Ekstrand et al. documented injuries over the course of a year in an amateur division consisting of 12 teams and 180 players. They recorded 256 total injuries in 124 players. Twelve of the 256 injuries (5%) were localized to the back region.77 Schmidt-Olsen et al. followed a cohort of 496 youth players aged 12–18 for 1 year and found that back injuries accounted for 14% of all injuries suffered.78 They proposed that back problems in youth players may be associated with growth. In addition, they noted that few players included prematch warm up routines that focused on the lower back. While acute vertebral fractures are rare, there is anecdotal evidence that there may be an increased incidence of pars stress fractures.79 Supporting this claim is a recent study of 28 soccer players with activity-related low back pain that utilized SPECT imaging techniques to find that 82% of patients had evidence of increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior elements of the lumbar spine. Of the 35 instances of spondylolysis, 25 were reported to be complete fractures, while 10 were noted to be incomplete.80

Ostenberg and Roos followed 123 female players from eight teams of different levels during one season. Injuries to the back accounted for 11% of all injuries that resulted in absence from at least one practice or game.81 Kibler82 logged injury data from 480 games and 74 900 player-hours over a 4-year period from the Bluegrass Invitational Soccer Tournament that included male and female players aged 12–19. He found a 10.9% incidence of injury to the torso, which included the abdomen, spine, and genital areas, and an 8% incidence of injury to the head and neck.

Functional considerations

Traumatic spine injuries in soccer are rare. While the majority of spine-related injuries are attributed to lumbar strain, the cervical spine is also susceptible to injury. Soccer is a unique sport in that the head is used in a functional capacity to pass, trap, and shoot the ball. Heading requires quick thrusts of neck flexion and extension, often combined with rotation and side bending. It has been suggested that soccer players are at a higher risk for development of cervical degenerative disc disease when compared to nonsoccer players of the same age group.83

Cycling

Overview

Studies indicate a high incidence of spine-related pain in cyclists. Although the majority of research focuses on traumatic injuries, there is a small amount of literature describing overuse injuries in both road and off-road cycling. In addition, cycling is a common component to various other endurance sports such as triathlons, cyclocross, and adventure racing. In regard to neck pain, a population survey of 4500 individuals found that regular cycling was a strong independent risk factor for persistent neck pain (OR 2.0–2.4).84 Weiss evaluated 132 riders who completed an 8-day bicycle tour over a distance of 500 miles. He found that 20.4% of all participants reported neck and shoulder pain.85 An even higher prevalence of neck pain was found in a questionnaire based study of 294 male and 224 female recreational cyclists. Forty-nine percent of cyclists reported neck pain, which was the most common anatomic site of complaint. In addition, females were found to be 1.5 times more likely to develop neck complaints than males.86

The prevalence estimates of low back pain in cyclists range from 2.7% to 60%, depending upon the type of cycling and skill level involved.18,86–89 In a study of 92 Japanese triathletes, low back pain was reported by 32% of athletes during the previous year and accounted for 28% of all injuries reported. Cycling was believed to be a major risk factor for development of low back pain in this population.88 Kronisch and Rubin surveyed 265 mountain bikers in the United States and reported complaints of back pain in 37% of respondents.87 In 1996, Callaghan and Jarvis investigated musculoskeletal injuries in over 500 elite British Cycling Federation cyclists. They found that low back pain was the most frequently encountered problem in this population, accounting for 60% of complaints.89

Functional considerations

The lumbar spine and the pelvis represent a significant point of support from which the power derived from the lower extremities is transmitted to the pedals. In the racing position, the lumbar spine is placed into a kyphotic position with increased pressure on the intervertebral discs. However, it appears that using the upper limbs to support the body decreases intradiscal pressure by distributing load.90

The customization of the bicycle setup for the individual athlete is of utmost importance. Handlebar position that is too high may lead to accentuated lumbar lordosis and increased stress on the posterior elements of the spine. Handlebar position that is too low, increases lumbar flexion and increases the load upon the intervertebral disc. Too long of a stem will cause the rider to be stretched out too far and necessitate holding the neck back, placing stress upon the neck and shoulders. Alterations in bike seat positioning also cause changes in the biomechanics of the lumbar spine. High seats cause the rider to laterally flex the lumbar spine toward the pedal. The incline of the saddle alters the amount of lumbar lordosis and may be adjusted to relieve back pain. In addition, good flexibility of the hamstrings will allow the lumbar spine to achieve a more lordotic position.91–93

Racquet sports

Overview

Overuse injuries of the low back are common in tennis players, but there are few data available that analyze the incidence and distribution of specific pain generators in back injury. According to Saal, the most common injuries appear to be soft tissue injury to the thoracic and lumbar regions, upper lumbar and thoracolumbar Z-joint injury, and disc disease.94 Chard and Lachmann studied 631 injuries occurring during racquet sports and found a 12% incidence of back injury.95 Another study evaluated professional men tennis players and found that approximately 38% reported missing at least one tournament due to lumbar pain.96 A recent study by Saraux et al. comparing recreational level tennis players to controls found no significant difference between the two groups when comparing reports of low back pain or sciatica during the week prior to survey.97

Functional considerations

Tennis players and athletes involved in other racquet sports subject the spine to repetitive hyperextension and rotational movements. Compared to other strokes in tennis, the serve and overhead volley place the highest load through the spinal motion segment. During the service toss, the spine is initially subject to hyperextension, rotation, and lateral flexion. This represents a loading phase through the kinetic chain. Upon striking the ball, force transfer occurs from the lower extremities through the spine to the shoulder joint, and finally the racquet. Inappropriate technique or weakness at any level of the kinetic chain may increase stress upon subsequent segments due to uncoupling of the pelvic and shoulder rotation. Improper location of toss often leads to hyperextension of the spine in order to make racquet contact. During the forehand and two-handed backhand strokes, the lumbar spine is subject to approximately 90° of axial rotation. Limited range of motion in the hips or uncoordinated rotation of the pelvis with the shoulders will place greater stress on the spinal motion segments. Alternatively, the one-handed backhand requires less rotation of the lumbar segments, decreasing the stress placed upon the lumbar spine.

1 Herring SA, Weinstein SM. Assessment and nonsurgical management of athletic low back injury. In: Nicholas JA, Hershman EB, editors. The lower extremity and spine in sports medicine. St Louis: Mosby; 1995:1171-1197.

2 Trainor TJ, Wiesel SW. Epidemiology of back pain in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(1):93-103.

3 Sword L, Hellstrom M, Jacobsson B, et al. Disc degeneration and associated abnormalities of the spine in elite gymnasts. A magnetic resonance imaging study. Spine. 1991;16:437-443.

4 Ong A, Anderson J, Roche J. A pilot study of the prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration in elite athletes with lower back pain at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:263-266.

5 Selby D. The structural degenerative cascade. In: Schofferman J, editor. Spine care: diagnosis and conservative treatment. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:9-16.

5a Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Bernard TN. Managing low back pain, 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.

6 Sassmannshausen G, Smith BG. Back pain in the young athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(1):121-132.

7 Waicus KM, Smith BW. Back injuries in the pediatric athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(1):52-58.

8 Anderson SJ. Children and adolescents. In: Cole AJ, Herring SA, editors. Low back pain handbook: A guide for the practicing physician. Philadelphia: Hanley and Belfus; 2003:413-435.

9 Tall RL, DeVault W. Spinal injury in sport: epidemiological considerations. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12(3):441-448.

10 Sward L, Hellstrom M, Jacobsonn B. Acute injury to the ring apophysis and intervertebral disc in adolescent gymnasts. Spine. 1990;15:144-148.

11 Weiker GG. Evaluation and treatment of common spine and trunk problems. Clin Sports Med. 1989;8:399-417.

12 Cirillo JV, Jackson DW. Pars interarticularis stress reaction, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis in gymnasts. Clin Sports Med. 1985;4:95-110.

13 Micheli L, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:15-18.

14 Lament LE, Einola S. Spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop Scand. 1961;82:45.

15 Jackson DW, et al. Stress reaction involving the pars interarticularis in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9:304.

16 Rossi F. Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis and sports. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1978;18:317.

17 Brown PG, Lee M. Trampoline injuries of the cervical spine. Ped Neurosurg. 2000;32:170-175.

18 Standaert CJ, Herring SA, Cole AJ, et al. The lumbar spine in sports. In: Cole AJ, Herring SA, editors. Low back pain handbook. Philadelphia: Hanley and Belfus; 2003:385-404.

19 Mazzeo RS, Cavanaugh P, Evans WJ, et al. Exercise and physical activity for older adults: American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:992.

20 Conte S, Requa RK, Garrick JG. Disability days in major league baseball. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):431-436.

21 Kane SM, House HO, Overgaard KA. Head-first versus feet-first sliding: A comparison of speed from base to base. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(6):834.

22 Watkins RG. Baseball. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:436-455.

23 Koichi S, Katoh S, Sakamaki T, et al. Three successive stress fractures at the same vertebral level in an adolescent baseball player. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):606-610.

24 Meyers MC, Brown BR, Bloom JA. Fast pitch softball injuries. Sports Med. 2001;31(1):61-73.

25 Casazza BA, Rossner K. Baseball/lacrosse injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 1999;10(1):141-157.

26 Herkowitz HN, Paolucci JP, Abdenour MA. Basketball. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:430-435.

27 Meeuwisse WH, Sellmer R, Hagel BE. Rates and risks of injury during intercollegiate basketball. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:379-385.

28 Hickey GJ, Fircker PA, McDonald WA. Injuries of young elite female basketball players over a six-year period. Clin J Sport Med. 1997;7(4):252-256.

28a Henry JH, Lareau B, Neigut D. The injury rate in professional basketball. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10(1):16-18.

29 Rossi F, Dragoni S. Lumbar spondylolysis: occurrence in competitive athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1990;30:450-452.

30 Herskowitz A, Selesnick H. Back injuries in basketball players. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12(2):293-306.

31 Viere RG. Special populations and problems: elderly patients. In: Cole AJ, Herring SA, editors. Low back pain handbook: A guide for the practicing physician. Philadelphia: Hanley and Belfus; 2003:437-452.

32 Lebwohl NH. Diving. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:391-396.

33 Kim DH, Vaccaro AR, Berta SC. Acute sports-related spinal cord injury: contemporary management principles. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22:501-512.

34 Rubin BD. The basis of competitive diving and its injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1999;18(2):193.

35 Groher W, Heindensohn P. Backache and x-ray changes in diving. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1970;108:51.

36 Halpern B, Thompson N, Curl WW, et al. High school football injuries: Identifying the risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(Supp 1):S113-S117.

37 Watkins RG. Neck injuries in football. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:314-336.

38 Hagel BE, Fick GH, Meeuwisse WH. Injury risk in men’s Canada West University football. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(9):825.

39 Torg JS, Truex RCJr, Marshall J, et al. Spinal injury at the level of the third and fourth cervical vertebrae from football. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1977;59:1015-1019.

40 Torg JS, Sennett B, Vegso JJ, et al. Axial loading injuries to the middle cervical spine segment. An analysis and classification of twenty-five cases. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:6-20.

41 Torg JS, Pavlov H, Genuario SE, et al. Neurapraxia of the cervical spinal cord with transient quadriplegia. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1986;68:1354-1370.

42 Watkins RG. Lumbar spine injuries in football. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St Louis: Mosby; 1996:343-348.

43 Gatt CJJr, Hosea TM, Palumbo RC, et al. Impact loading of the lumbar spine during football blocking. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:317-321.

44 Ferguson RJ, McMaster JH, Stanitski CL. Low back pain in college football linemen. Am J Sports Med. 1974;2:63-69.

45 McCarroll JR, Miller JM, Ritter MA. Lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in college football players. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:404.

46 Shaffer B, Wiesel S, Lauerman W. Spondylolisthesis in the elite football player: an epidemiologic study in the NCAA and NFL. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10:365-370.

47 Simon RL, Spenger D. Significance of lumbar spondylolisthesis in college football players. Spine. 1981;6:172.

48 Beutler WJ, Fredrickson BE, Murtland A, et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine. 2003;28(10):1027.

49 Tewes DP, Fischer DA, Quick DC, et al. Lumbar transverse process fractures in professional football players. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(4):507-509.

50 Day AL, Friedman WA, Indelicato PA. Observations on the treatment of lumbar disc disease in college football players. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:72.

51 Virgin HW. Football injuries to the skeletal system. Compr Ther. 1985;11(1):19.

52 Gerbino PG, d’Hemecourt PA. Does football cause an increase in degenerative disease of the lumbar spine? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(1):47-51.

53 Torg JS, Vegso JJ, O’Neill MJ, et al. The epidemiologic, pathologic, biomechanical, and cinematographic analysis of football-induced cervical spine trauma. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(1):50-57.

54 Torg JS, Guille JT, Jaffe S. Injuries to the cervical spine in American football players. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2002;84A(1):112-122.

55 Weinberg J, Rokito S, Silber JS. Etiology, treatment, and prevention of athletic ‘stingers.’. Clin Sports Med. 2003;21:493-500.

56 Dossett AB, Watkins RG. Stinger injuries in football. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:337-342.

57 Watkins RG. Lumbar disc injury in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(1):147-165.

58 Gosheger G, Liem D, Ludwig K, et al. Injuries and overuse syndromes in golf. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):438.

59 Hosea TM, Gatt CJ. Back pain in golf. Clin Sports Med. 1996;15(1):37-53.

60 Ekin JA, Sinaki M. Vertebral compression fractures sustained during golfing: report of three cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68(6):566-570.

61 Vad VB, Bhat AL, Basrai D, et al. Low back pain in professional golfers: The role of associated hip and low back range-of-motion deficits. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):494-497.

62 Wallace P, Reilly T. Spinal and metabolic loading during simulations of golf play. J Sports Sci. 1993;11:511.

63 Oseid S, Evjenth G, Evjenth O, et al. Lower back trouble in young female gymnasts: Frequency, symptoms and possible causes. Bull Phys Educ. 1974;10:25-28.

64 Dixon M, Fricker P. Injuries to elite gymnasts over 10 years. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1993;25:1322-1329.

65 Garrick JG, Requa RK. Epidemiology of women’s gymnastics injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:261-264.

66 Katz DA, Scerpella TA. Anterior and middle column thoracolumbar spine injuries in young female gymnasts: Report of seven cases and review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:611.

67 Kurzweil PR, Jackson DW. Gymnastics. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:456-464.

68 Hutchinson MR. Low back pain in elite rhythmic gymnasts. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 1999;31(11):1686.

69 Bono CM. Low back pain in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2004;86A(2):382-396.

70 Goldstein JD, Berger PE, Windler GE. Spine injury in gymnasts and swimmers: An epidemiologic investigation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:463.

71 Sward L. The thoracolumbar spine in young elite athletes. Current concepts on the effects of physical training. Sports Med. 1992;13(5):357-364.

72 Jackson DW, Rettig A, Wiltse LL. Epidural cortisone injections in the young athletic adult. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:239.

73 Sward L, Hellstrom M, Jacobsson B, et al. Back pain and radiologic changes in the thoraco-lumbar spine of athletes. Spine. 1990;15:124.

74 Saal JA. Lumbar injuries in gymnastics. In: Hochschuler SH, editor. Spine – state of the art reviews: spine injuries in sports. Philadelphia: Hanley and Belfus; 1990:426-440.

75 van Akkerveeken PF. Soccer. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:515-521.

76 Tysvaer AT. Cervical disc herniation in a football player. Br J Sports Med. 1985;19(1):43-44.

77 Ekstrand J, Gillguist J. The avoidability of soccer injuries. Int J Sports Med. 1983;4:124.

78 Schmidt-Olsen S, Jorgensen U, Kaalund S, et al. Injuries among young soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:273-275.

79 Kraft DE. Low back pain in the adolescent athlete. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(3):643.

80 Gregory PL, Battand ME, Kerslake RW. Comparing spondylolysis in cricketers and soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:737-742.

81 Ostenberg A, Roos H. Injury risk factors in female European football: A prospective study of 123 players during one season. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10(5):279.

82 Kibler WB. Injuries in adolescent and preadolescent soccer players. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1993;25(12):1330-1332.

83 Sortland O, Tysvaer AT. Brain damage in former association football players: An evaluation by cerebral computed tomography. Neuroradiology. 1989;31(1):44-48.

84 Hill J, Lewis M, Papageorgiou AC, et al. Predicting persistent neck pain: a 1-year follow-up of a population cohort. Spine. 2004;29(15):1648-1654.

85 Weiss BD. Nontraumatic injuries in amateur long distance bicyclists. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(3):187-192.

86 Wilber CA, Holland GJ, Madison RE, et al. An epidemiological analysis of overuse injuries among recreational cyclists. Int J Sports Med. 1995;16(3):201-206.

87 Kronish RL, Rubin AL. Traumatic injuries in off-road bicycling. Clin J Sports Med. 1994;4(4):240-244.

88 Manninen JS, Kallinen M. Low back pain and other overuse injuries in a group of Japanese triathletes. Br J Sports Med. 1996;30(2):134-139.

89 Callaghan MJ, Jarvis C. Evaluation of elite British cyclists: the role of the squad medical. Br J Sports Med. 1996;30(4):349-353.

90 Usabiaga J, Crespo R, Iza I, et al. Adaptation of the lumbar spine to different positions in bicycle racing. Spine. 1997;22(17):1965-1969.

91 Mellion MB. Neck and back pain in bicycling. Clin Sports Med. 1994;13(1):137-164.

92 Mellion MB. Common cycling injuries. Management and prevention. Sports Med. 1991;11(1):52-70.

93 Salai M, Brosh T, Blankstein A, et al. Effect of changing the saddle angle on the incidence of low back pain in recreational bicyclists. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33(6):398-400.

94 Saal JA. Tennis. In: Watkins RG, editor. The spine in sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:499-504.

95 Chard MD, Lachmann MA. Racquet sports-patterns of injury presenting to a sports injury clinic. Br J Sports Med. 1987;21(4):150-153.

96 Marks MR, Haas SS, Wiesel SW. Low back pain in the competitive tennis player. Clin Sports Med. 1988;7(2):277-287.

97 Saraux A, Guillodo Y, Devauchelle V, et al. Are tennis players at increased risk for low back pain and sciatica? Revue de Rhumatisme (English Edition). 1999;66(3):143-145.