2 Epidemiology and the Care of Children with Complex Conditions

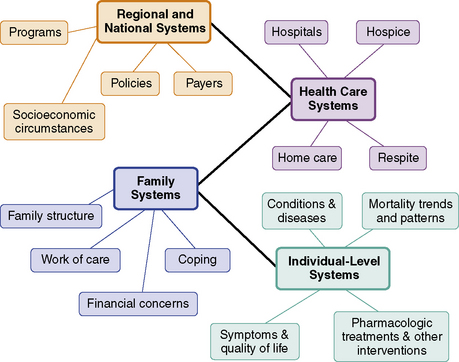

In this chapter, we apply an epidemiologic framework of investigation to the issues and challenges that we confront in pediatric palliative and hospice medicine. When people casually refer to the epidemiology of a particular illness or disease, they often mean the body of knowledge about the condition—who it affects and why, what happens to persons with the condition, and what is known about the effect of treatment for the condition—that has been built up through epidemiologic research. We try to encapsulate some of what is known about pediatric patients who receive palliative and hospice care, or more broadly children who die, while acknowledging that because these children suffer from a variety of conditions, ranging from acute trauma to complex and chronic, we must be. While presenting this information, we will also emphasize a systems-oriented perspective to the study of pediatric palliative and hospice care. While the Hippocratic practitioner of the medical art who authored the opening epigraph certainly emphasized core aspects of this systems perspective, we need to expand our practice and our science beyond the disease, patient, and a single healer. Many readers likely already consider the experience of individual children as best understood in the context of their family and healthcare, education, and other social services, as well as the systems of payment for services and laws and regulations that influence these other systems (Fig. 2-1). Our scheme is no more complicated than this common sense of the hierarchy of influences on the lives of children with life-threatening illness. Such a scheme provides not only an organized approach to the study of pediatric palliative and hospice care, but also provides insights as to how we can improve these systems. To make this scheme as down-to-earth as possible, we will over the course of the chapter illustrate aspects of the different levels by tracing the profile of a single child.

Fig. 2-1 Multi-level systems influencing experience of children receiving palliative or hospice care.

Patients and Individual-Level Systems

Conditions and diseases

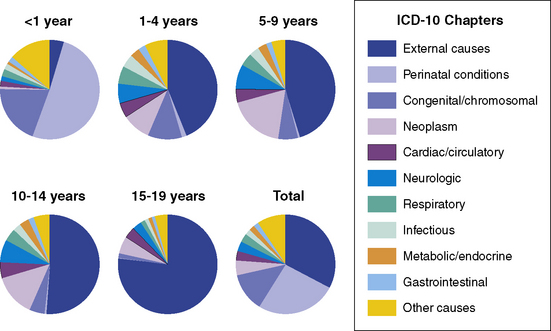

Not all children who die receive palliative care services, but national profiles of children who die provide the strongest epidemiological evidence to characterize the conditions and diseases of children receiving pediatric palliative care. Examining mortality data in the United States between 1999 and 2006 (Fig. 2-2), one notices immediately that infant deaths are due mostly to specific perinatal conditions, such as premature birth and congenital syndromes or chromosomal disorders, whereas older children are most likely to die from external causes, such as traumatic injury.

Fig. 2-2 Major causes of pediatric death in the United States, 1999-2006.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

For children with CCCs, congenital and chromosomal abnormalities were associated with 5819 (20.3% of 28,527 total) infant and 1087 (4.4%) child deaths, diseases of the nervous system caused 373 (1.3%) infant and 1173 (4.8%) child deaths. Deaths from cancer, which is perhaps the condition most strongly associated with the imagery of palliative care in mind of the public and much of the medical profession, accounted for only 141 (0.5%) infant deaths and 2150 (8.9%) deaths past infancy. A few studies of patients enrolled in pediatric palliative care programs support the evidence of diverse conditions in this population. In a recent study of 8 pediatric palliative care programs in Canada, patients had as their primary diagnosis nervous system disorders (39.1%), cancer (22.1%), or perinatal-onset conditions or congenital anomalies (22.1%).1

Trends and age-specific patterns of mortality

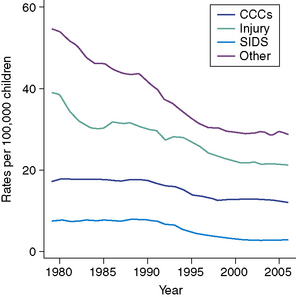

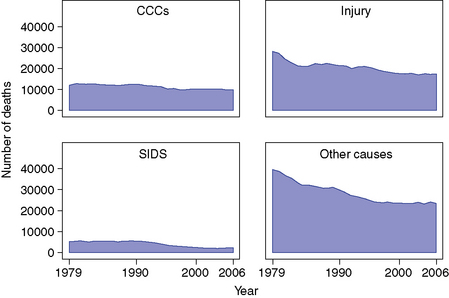

Over the past century, child mortality has been declining for both children suffering from trauma and from complex chronic conditions. Examining U.S. mortality data from 1979 to 2006, the rates of death attributed to CCCs as well as injury, sudden infant death syndrome, and other causes declined substantially (Fig. 2-3), with the corresponding numbers of deaths also declining but less so since 2000 (Fig. 2-4).

Fig. 2-3 Trends in the rates of pediatric death by causes, 1979-2006.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

Fig. 2-4 Trends in the number of pediatric death by causes, 1979-2006.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

One published study focused on the interval between 1979 and 1997, when the annual death rate due to non-cancer and cancer-related CCCs declined for almost every age group (from a 7.1% decline for infants with cancer to a 49.9% decline for 1 to 4 year olds dying from non-cancer CCCs). The one exception to this decline was the mortality attributed to non-cancer CCCs among 20 to 24 year olds for whom the rate of death actually increased by 11.6% over this 18-year interval, which may be due to the longer lifespan of younger children with CCCs dying at later ages.2 For this reason, studies of pediatric deaths and palliative care need to include the experiences of young adults, perhaps into their 20s or 30s, who die from conditions with congenital or childhood-onset.

Symptoms and quality of life

The management of physical and psychological symptoms is of utmost importance in palliative care. Most studies published are on bereaved parents of children with cancer. In one such study, 96 bereaved Australian parents of children with cancer reported that, in the last month of life, 84% of children suffered from at least one physical symptom (pain, fatigue, poor appetite, constipation, dyspnea, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and seizures), with pain, fatigue, and poor appetite the most frequent.3 Nearly half (43%) of children suffered from three or more physical symptoms. Parents also reported that 42% of children had been “more than a little sad,” 38% experienced “little or no fun,” and 21% were “often afraid.” In a Swedish study of 449 bereaved parents of children with cancer, physical fatigue was the most frequently reported symptom (86%) to have a higher or moderate impact on the child’s well-being, with reduced mobility (76%), pain (73%), and decreased appetite (71%) also major concerns.4 In this study, parents were more likely to report anxiety in children older than 9 years of age than in younger children (relative risk [RR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2-2.6) and 16 years of age (RR 2.0, 1.3-2.9). Children also suffered from difficulties in swallowing, depression, reduced mobility, impaired speech, swelling, disturbed sleep due to anxiety, and urinary problems. Problems with breathing during the last day of life, and with loss of motor function in the last week of life, were also reported by 28 bereaved parents whose children had been enrolled in a pediatric hospice program in St. Louis.5 Another study of 65 parents of 52 children reported similar symptoms, which did not differ according to patient gender, disease, or location of death, such as the ICU, elsewhere in hospital, or home.6 A study of bereaved parents of 48 children who died from cancer also cited that their children suffered from anxiety, which was not treated effectively.7 Given the prevalence of symptoms, and the nature of the child’s condition, it is challenging to measure quality of life for children receiving palliative care services, especially using generalized instruments that may not be suitable for this population of children.8 Nevertheless, much remains to be done in improving the treatment of symptoms in this population.

Pharmacologic treatments and other interventions

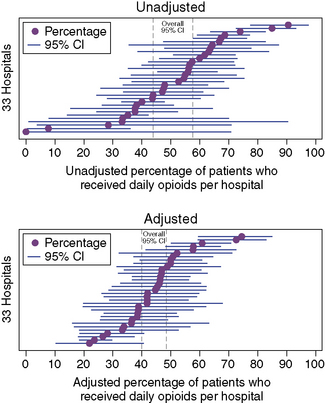

The use of specific medications appears to vary substantially across hospitals and hospices. For instance, in a study of 1466 pediatric oncology patients who died in children’s hospitals, the proportion of patients who received opioids daily during their last week ranged across the hospitals from zero to 90.5%, a variation in practices that did not diminish substantially even after adjustment for patient characteristics (Fig. 2-5).

Medications are only one of many possible interventions used in palliative or hospice care or end of life situations to ameliorate symptoms or improve the quality of life. Much less is known about the epidemiology of other interventions, such as a child’s exposure to complementary and alternative medical (CAM) practices. We do know that in one study of 92 parents of children with cancer in the United States, 49% reported that their children used at least one type of CAM and 20% used herbal remedies, homeopathy, or vitamins in the two months preceding the survey,9 which suggests if any of these children died, some likely continued to receive CAM treatments at the end of life.

Family Systems

The experience of children receiving pediatric palliative care is clearly affected by a variety of specific aspects of their particular families. The structure and membership of a family as well as patterns of family organization and function, such as patterns of communication, cohesion among members, hierarchy, and adaptability to change, influences the care of children with complex chronic conditions.10 Family structure shapes how tasks are divided and roles are assigned in caring for the child, whereby one parent often assumes primary physical care for the patient, and the other parent or other family members manage care of the household and siblings. Structure also dictates how families respond to and regulate their intense emotional reactions to a child’s illness, which influence daily symptom management, soothing the ill child, and making critical end-of-life decisions. Family structure critically affects how care is performed, and is in turn affected by the family’s finances, their social and cultural backgrounds or community, and their religious and spiritual beliefs and practices. To varying degrees, the medical literature provides useful data and knowledge about each of these topics.

Family structure

Families can have many different structures, and families of children with complex chronic conditions are no different. In two-parent married households, research has reported mixed results as to the effects on the marriage. Some studies, such as a case-control study of marital quality in mothers and fathers parenting children with spina bifida, report no difference in marital distress than in parents of healthy children.11 Another study on the same disease reports marital breakdown.12 Other studies, such as one on functioning in parents of children with cancer, suggest that while marital difficulties may occur, positive benefits such as feeling closer as a family and supporting each other may offset the stresses.13 When parents are divorced, communication difficulties may exist, especially when the nonresidential parent has a different opinion about the child’s care than that of the custodial parent.14 Single-parent households have been less frequently studied,15 but some evidence suggests that single mothers of children with cystic fibrosis may have higher stress-related symptoms and that their children may have higher hospitalization rates;16 another study on handicapped children suggests that single mothers have greater difficulty with finances, but also were more flexible in adapting to new family roles and arrangements.17 Step-parents in the home also alter the family structure.18

Siblings add another dimension. While the national percentage of children with complex chronic conditions who have siblings is unknown, meta-analyses investigating the effects of childhood chronic illness on siblings suggests a modest, negative effect on psychological functioning, peer activities, and cognitive development, with lower scores reported by parents than by the siblings themselves.19,20 Recommendations for siblings include providing information about their brother’s or sister’s illness early on, group discussions, and informing school personnel.21

Another aspect of families that we can consider concerns other social and cultural characteristics. Various studies indicate that racial and ethnic minorities may have difficulties with trust and communication with the medical profession, poverty, and different belief systems and family structures.22–25 Religion and spirituality are very important to families, but their impact is not uniform nor prescriptive.26,27

The work of care

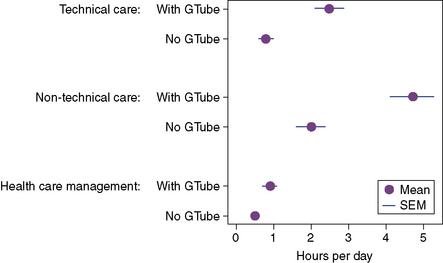

The work of care consists of the effort, labor, and various tasks in which parents and other family members engage in to care for the child with a complex chronic condition and for the family system. Daily tasks include administering medications, feeding and bathing, providing emotional support, and monitoring any changes in the child’s health.28–32 Parents also are responsible for managing their child’s medical care by arranging and bringing their child to appointments and filling out copious amounts of paperwork,33 while creating an environment where their child can have as normal a life as possible.34 These efforts can occupy a great deal of time.35 One study of parents whose children had gastrostomy tubes, compared to parents whose children did not, found parents in the first group devoted more than 7 hours a day to technical and non-technical care of the child compared to 3 hours in the second group (Fig. 2-6).36 How this work is organized, distributed, and completed likely varies across family structures, and some evidence also exists that stronger family function is related to better execution of disease management activities.37–39

Fig. 2-6 Number of hours per day devoted by parents to caring for children with gastrostomy tubes.

(Data abstracted from Heyman MB, Harmatz P, Acree M, Wilson L, Moskowitz JT, Ferrando S, et al. Economic and psychologic costs for maternal caregivers of gastrostomy dependent children. J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):511-516.)

Coping

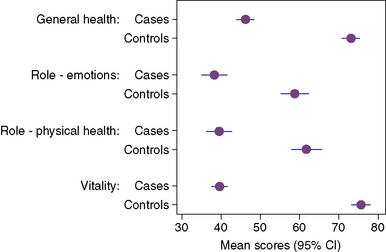

Parents and siblings have been observed to suffer from an array of psychological and physical forms of distress: parents report depression, grief, guilt, and anxiety as well as problems such as insomnia, headaches, and musculoskeletal pain. One study of parents of children with severe cardiac disease, compared to control parents of healthy children, found substantial decrements in the parents quality of life in general and specifically regarding emotions, physical health, and vitality (Fig. 2-7).40 Siblings struggle with fears, traumatic reactions, isolation, difficulties in school and social settings, and the behavior problems that result.41

Financial concerns

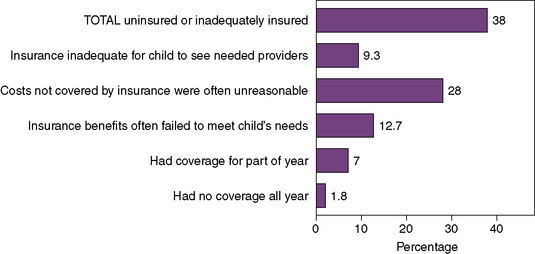

Related to both the work of care and coping is a family’s financial concerns. In particular, three areas of finances—insurance, paid work, and out-of-pocket expenses—are affected by caring for a child with a complex chronic condition. Due to the high costs of care, families may have difficulty finding or keeping insurance coverage, and may find that certain services are not covered or caps on spending prevent other services from being used.42 The result is that 38% of the U.S. population of parents of children with special health care needs are either uninsured or inadequately insured (Fig. 2-8),43 a phenomenon that is especially pressing as the adolescents transition into adulthood.44 Often in families caring for a child with a complex chronic condition, one family member, usually the mother, decides to stay at home, forsaking the income and benefits provided by paid work.45,46 Out-of-pocket expenditures also are very high, and may further impoverish families.47 Very poor families, however, may actually be at a slight advantage due to the infusion of additional resources and outside attention into the home.48

Fig. 2-8 Levels of inadequate health insurance among children with special healthcare needs.

(Data abstracted from Newacheck PW, Houtrow AJ, Romm DL, Kuhlthau KA, BloomSR, Van Cleave JM, et al. The future of health insurance for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e940-947.)

Healthcare Systems

Care in the home

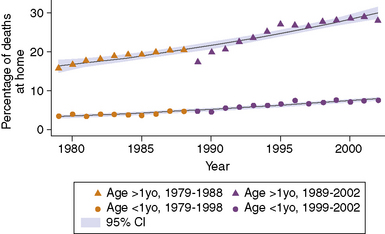

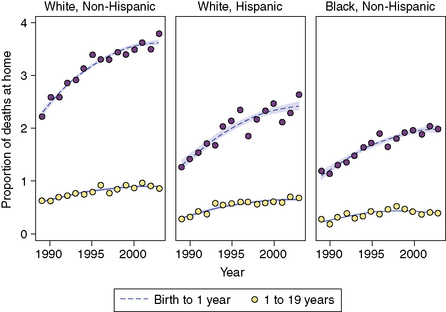

Pediatric palliative and hospice home care is intended to increase the quality of life of patients and families, and some, if not most, families prefer being at home to care for the child.30 From 1989 to 1993, only 12.3% of children with CCCs died in the home; in 1999 to 2003, 17.7% of children with CCCs died in the home. In the same period, hospital deaths declined and deaths at all other sites and care institutions remained comparably stable.49 This pattern of a rising proportion of pediatric deaths attributed to CCCs occurring at home is traceable to 1979 (Fig. 2-9). Over the same time periods, stark differences in the proportion of death that occurred at home are evident and persistent among patients classified on their death certificates as white, Hispanic, or black (Fig. 2-10).49

Fig. 2-9 Rising percentage of pediatric CCC-related deaths occurring at home, 1979-2002.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

Fig. 2-10 Differences in proportion of CCC-related deaths occurring at home by race and/or ethnicity.

(Data abstracted from Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Satchell M, Zhao H, Kang TI. Shifting place of death among children with complex chronic conditions in the United States, 1989-2003. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2725-2732.)

Home care usually involves the partnering of skilled nurses with the parents, who are able to share knowledge and divide tasks related to the work of care.50 Issues to be considered in home care include the work of care, impact on the family, the likelihood of adverse events, and cost.30,51–54 In a study of parents of 48 children who died from cancer, while only 41% of parents provided palliative care in the home and 48% of children died at home, 88% of parents chose “at home” as the most appropriate location of death in hindsight.7

Hospice care

While in general, little is known about the hospice care services that dying children receive, these services are generally thought to be simultaneously useful but underused. Research has demonstrated rare differences in the use of hospice services, but whether these differences arise due to differential access, eligibility, or other reasons remains unknown. A study of Florida Medicaid pediatric patients who died revealed that only 11% received any hospice services, but those who did were more likely to be non-Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic black, have chronic conditions, and longer Medicaid enrollment than non-hospice users.55 In a study of pediatric oncologists, physicians with access to hospice that accepted patients receiving chemotherapy had more patients die at home, but not all hospices admit patients actively receiving chemotherapy.56 A broader survey of pediatric medical providers experienced in end-of-life care reported that 86% of responders thought hospice was beneficial, especially in the provision of non-medical services.57

Hospitals

While there is a trend of increasing hospice and home-based pediatric palliative care, pediatric death still occurs mostly in the hospital setting. From 1989 to 2003, 80.1% of childhood deaths resulting from CCCs occurred in the hospital (down from 85.7% in 1989 to 2003), with considerable variation in the location of death by CCC category.49 The same study also demonstrated that infants and racial and ethnic minorities, were more likely to die in the hospital than older children and non-minorities.

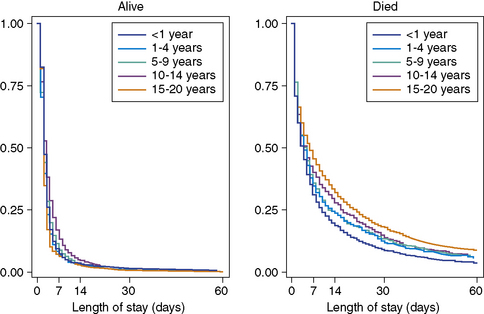

Hospitalizations of children with CCCs who subsequently died were characterized by long lengths of stay (Fig. 2-11), mechanical ventilation during their terminal admissions, and death in the intensive care unit. In a study that linked information from death certificates to hospital use records from 1990 to 1996 in Washington state, 458 infants with CCCs who died under a week of age spent 92% of their lives in the hospital, and 286 infants with CCCs who died during the second to twelve months of life spent 41% of all their lives in the hospital.58 For children and young adults with CCCs, the median number of days spent in the hospital in the year preceding death was 18, and only a third of this group was hospitalized until the last week of life. Across all age groups, rates of hospital use increased closer to the child’s death. Half of hospitalized infants and 19% of children and young adults with CCCs were mechanically ventilated during their terminal admission. Studies from hospitals in a range of countries (the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands), suggest that although a number of deaths take place in the operating room and emergency departments, most pediatric deaths occur in the intensive care unit.59–62 In a study of a United Kingdom children’s hospital, infants with congenital malformations and perinatal conditions were most likely to die in the ICU (OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.65 to 1.35) and older children with cancer were the most likely to die outside the ICU (OR 6.5, 95% CI 4.4 to 9.6).63

Fig. 2-11 Length of hospital stay for pediatric patients discharged alive or who died, 2006.

(Data from KID 2006, Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.)

Over the past decade, hospital-based palliative care services have begun in many pediatric hospitals across the country. An evaluation of the impact of one such interdisciplinary program in Boston documented, after the program’s establishment, an increased frequency of hospice discussions (76% vs. 54%, for an adjusted risk difference of 22%), earlier documentation of do-not-resuscitate orders (18 vs. 12 days), and fewer deaths in the intensive care unit or in other hospitals (decrease of 16%). Parents also reported that their child suffered less pain (adjusted risk difference of 19%), and that they felt more prepared during their child’s last month of life and at the death.64 In another study on the impact of a pediatric palliative care program in Germany, 69% of families preferred to have their child at home for the death compared to 18% of families before the program was instituted.65

Respite and other modalities of care

Beyond hospital and hospice care, other modes may also be useful for dying children. Broadening the definition of the population in need to encompass children with complex or special healthcare needs, respite care provides parents with time off from being in charge of the care. Respite care also has different meanings and purposes attributed to it by different families.66 In a study among caregivers of children with cerebral palsy in Canada, 46% of caregivers reported using respite services in the past year, and 90% of caregivers indicated that respite was beneficial for both the child and family.67 In another study of children with special healthcare needs, researchers demonstrated that a program in an emergency department setting to provide telephone advice and care coordination enhanced parental satisfaction with emergency care.68

Regional and National Systems

Programs

In general, pediatric palliative and hospice care programs are characterized as being interdisciplinary and focused holistically on both the child and the family, with important functions being pain management, coordination of care, and decision-making support. For example, the Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project enrolled 41 patients over a 2-year period (1999 to 2001) whose ages ranged from infancy to 22 years old, with 31 specific diagnoses in the population and 34% cancer diagnoses.69 Another program in Florida, the Partners in Care: Together for Kids (PIC:TFK) program, which uses government subsidies to create partnerships between state-employed care coordinators and home and community-based hospice staff, enrolled 468 children in the 3-year period between 2005 and 2008.70 The PIC:TFK program was intended to provide supportive services to families beginning at diagnosis, and 92% of the children were either newly diagnosed or mid-stage. Services received in years 1 and 2 were support counseling, 46%; respite, 22%; nursing care, 15%; activity therapies, 14%; personal care, 2.5%; bereavement care, 0.8%; and pain and symptom management, 0.1%. While pain and symptom management services usage was very low, the study authors suggested that these services may have been provided by physicians who were not associated with the PIC:TFK program. The PIC:TFK was funded by Children’s Hospice International in partnership with the U.S. government, other programs by the CHI partnership exist in Colorado, Kentucky, New York, Virginia, and Utah, and would benefit from being similarly profiled.

Policies

Both federal and state governments have been involved in crafting policies to address pediatric palliative care for families and providers. Federally, the best example remains the 1993 Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which protects parents who take time off to be with children receiving medical and psychiatric care from job loss. FMLA permits, among other things, both mothers and fathers to take unpaid leaves of absences from work while still receiving employer-provided health benefits. While the FMLA covers less than half of workers in the private sector, one study of employment statistics across the United States showed that the FMLA did increase leave coverage and usage without negatively impacting women’s employment or wages overall.71 In California, the “Nick Snow Children’s Hospice and Palliative Care Act of 2005” created a pilot waiver program to address provision of palliative care through home health and hospice agencies, funded by a partnership between Medi-Cal and California Children’s Services.

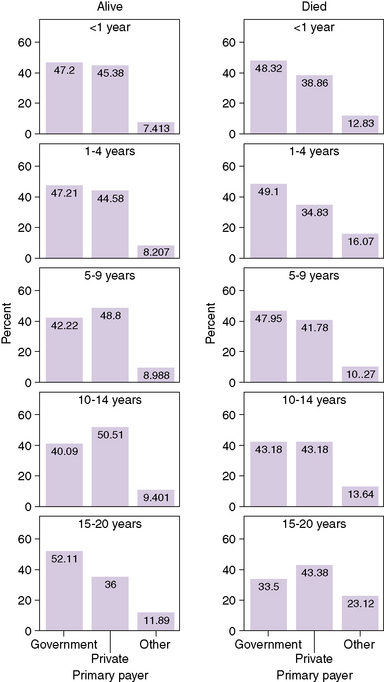

Payers and socioeconomic circumstances

The economics of health and healthcare have direct influences on the experiences of children and families receiving palliative and hospice care. According to data collected by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006 (Fig. 2-12), most children hospitalized in the United States who were discharged alive were insured either by government or private insurance, with less than 10% of patients having had no primary insurance (the slight exception being pediatric patients age 15 to 20 years, where 11.9% had no insurance). By contrast, among patients who died during their hospitalization, a larger percentage of patients in each age bracket had no primary insurance, and a smaller percentage had private insurance as their primary payer (with the exception again of the older adolescents, who upon reaching 18 years of age are no longer eligible for certain forms of government health insurance coverage).

Fig. 2-12 Primary payers of hospital care for children.

(Data from KID 2006, Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.)

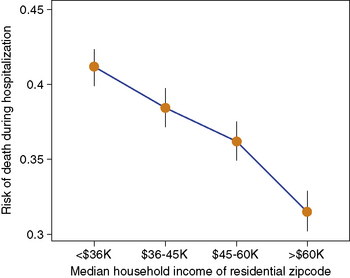

In the same U.S. hospitalization data, another economic aspect of childhood mortality is evident: the risk of dying during hospitalization is highest among patients from the poorest neighborhoods, and reduces across each step upward in median household income (Fig. 2-13). This observation, which accords with an extensive body of research connecting child wellbeing to socioeconomic circumstances,72 reveals the connections between all the layers of the systems that we have outlined. Those layers are from individual risk of having a life-threatening medical condition, through the impact on family finances of having a child with a CCC, to access to and usage of healthcare system services, to the programs and policies that shape the availability of payers and services.

International pediatric palliative care

Within the international setting, many national and multinational nonprofit organizations provide a support structure for independent programs based around the world by assisting with fundraising and advocacy. Multinational organizations such as Children’s Hospice International and the International Children’s Palliative Care Network link palliative care programs and hospices in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Uganda, India, Singapore, Argentina, Thailand, Indonesia, Costa Rica, and Belarus.73 In Europe, the European Association for Palliative Care provides a similar program for pediatric palliative care and hospice programs in Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, and other European countries. Within the United Kingdom, the Association for Children’s Palliative Care (ACT) and the Association of Children’s Hospices (ACH) network with individual programs and the British government to advocate for the best possible care.

Issues in pediatric palliative care differ by geopolitical regions in at least two major ways. First, causes of childhood mortality differ drastically around the globe. For example, in a study of death in children under 15 years in Mozambique between 1997 and 2006, 73.6% of deaths were attributable to communicable diseases, with 21.8% caused by malaria, 9.8% by pneumonia, and 8.3% caused by HIV/AIDS.74 In Africa, the large number of children living with HIV are intended recipients of many palliative care services.73,75 In a study on causes of mortality in children younger than 5 years of age in Iraq, diarrhea was the leading cause of death in both infants (49.8%) and children 12 to 59 months (43.4%).76 In the same study, researchers noted that cause of childhood death in Iraq often goes unreported when access to health services is limited, and most deaths occur at home. While causes of childhood mortality are certainly linked to broader geopolitical issues of overall morbidity and mortality, poverty, and health services availability and access, pediatric palliative care needs to adapt in each situation to meet the needs of local children.

Second, ethical perspectives about neonatal and childhood illness and death vary significantly around the world. The most obvious example concerns divergent views on euthanasia.77,78 More broadly, variations in how societies and cultures conceptualize the nature of childhood, parental responsibility, the parent-child relationship, and death likely all affect how pediatric palliative care policies and decisions are framed, understood, and implemented.

1 Widger K., Davies D., Drouin D.J., Beaune L., Daoust L., Farran R.P., et al. Pediatric patients receiving palliative care in Canada: results of a multicenter review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(6):597-602.

2 Feudtner C., Hays R.M., Haynes G., Geyer J.R., Neff J.M., Koepsell T.D. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E99.

3 Heath J.A., Clarke N.E., Donath S.M., McCarthy M., Anderson V.A., Wolfe J. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer: an Australian perspective. Med J Aust. 2010;192(2):71-75.

4 Jalmsell L., Kreicbergs U., Onelov E., Steineck G., Henter J.I. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1314-1320.

5 Hendricks-Ferguson V. Physical symptoms of children receiving pediatric hospice care at home during the last week of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(6):E108-E115.

6 Pritchard M., Burghen E., Srivastava D.K., Okuma J., Anderson L., Powell B., et al. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1301-e1309.

7 Hechler T., Blankenburg M., Friedrichsdorf S.J., Garske D., Hubner B., Menke A., et al. Parents’ perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220(3):166-174.

8 Huang I.C., Shenkman E.A., Madden V.L., Vadaparampil S., Quinn G., Knapp C.A. Measuring quality of life in pediatric palliative care: challenges and potential solutions. Palliat Med. 2009.

9 Martel D., Bussieres J.F., Theoret Y., Lebel D., Kish S., Moghrabi A., et al. Use of alternative and complementary therapies in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(7):660-668.

10 Patterson J. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. J Marriage Family. 2002;64:349-360.

11 Cappelli M., McGarth P.J., Daniels T., Manion I., Schillinger J. Marital quality of parents of children with spina bifida: a case-comparison study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15(5):320-326.

12 Martin P. Marital breakdown in families of patients with spina bifida cystica. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1975;17(6):757-764.

13 Barbarin O.A., Hughes D., Chesler M.A. Stress, coping, and marital functioning among parents of children with cancer. J Marriage Family. 1985;47(2):473-480.

14 Ganong L., Doty M.E., Gayer D. Mothers in post divorce families caring for a child with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18(5):332-343.

15 Brown R.T., Wiener L., Kupst M.J., Brennan T., Behrman R., Compas B.E., et al. Single parents of children with chronic illness: an understudied phenomenon. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007.

16 Macpherson C., Redmond A.O., Leavy A., McMullan M. A review of cystic fibrosis children born to single mothers. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87(4):397-400.

17 McCubbin M.A. Family stress and family strengths: a comparison of single- and two-parent families with handicapped children. Res Nurs Health. 1989;12(2):101-110.

18 Zarelli D.A. Role-governed behaviors of stepfathers in families with a child with chronic illness. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24(2):90-100.

19 Sharpe D., Rossiter L. Siblings of children with a chronic illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(8):699-710.

20 Barlow J.H., Ellard D.R. The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: an overview of the research evidence base. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32(1):19-31.

21 Lähteenmäki P.M., Sjöblom J., Korhonen T., Salmi T.T. The siblings of childhood cancer patients need early support: a follow up study over the first year. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(11):1008-1013.

22 Rehm R.S. Cultural intersections in the care of Mexican American children with chronic conditions. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29(6):434-439.

23 Elfert H., Anderson J.M., Lai M. Parents’ perceptions of children with chronic illness: a study of immigrant Chinese families. J Pediatr Nurs. 1991;6(2):114-120.

24 Williams H.A. A comparison of social support and social networks of black parents and white parents with chronically ill children. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(12):1509-1520.

25 McCubbin H.I., Thompson E.A., Thompson A.I., McCubbin M.A., Kaston A.J. Culture, ethnicity, and the family: critical factors in childhood chronic illnesses and disabilities. Pediatrics. 1993;91(5 Pt 2):1063-1070.

26 Feudtner C., Haney J., Dimmers M.A. Spiritual care needs of hospitalized children and their families: a national survey of pastoral care providers’ perceptions. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e67-e72.

27 Robinson M.R., Thiel M.M., Backus M.M., Meyer E.C. Matters of spirituality at the end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e719-e729.

28 Canam C. Common adaptive tasks facing parents of children with chronic conditions. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(1):46-53.

29 Monaghan M.C., Hilliard M.E., Cogen F.R., Streisand R. Nighttime caregiving behaviors among parents of young children with Type 1 diabetes: associations with illness characteristics and parent functioning. Fam Syst Health. 2009;27(1):28-38.

30 Wang K.W., Barnard A. Caregivers’ experiences at home with a ventilator-dependent child. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(4):501-508.

31 Kirk S., Glendinning C., Callery P. Parent or nurse? The experience of being the parent of a technology-dependent child. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(5):456-464.

32 Sullivan-Bolyai S., Deatrick J., Gruppuso P., Tamborlane W., Grey M. Constant vigilance: mothers’ work parenting young children with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18(1):21-29.

33 Osterlund C.S., Dosa N.P., Arnott Smith C. Mother knows best: medical record management for patients with spina bifida during the transition from pediatric to adult care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:580-584.

34 Williams C. Alert assistants in managing chronic illness: the case of mothers and teenage sons. Sociol Health Illn. 2000;22(2):254-272.

35 Curran A.L., Sharples P.M., White C., Knapp M. Time costs of caring for children with severe disabilities compared with caring for children without disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(8):529-533.

36 Heyman M.B., Harmatz P., Acree M., Wilson L., Moskowitz J.T., Ferrando S., et al. Economic and psychologic costs for maternal caregivers of gastrostomy-dependent children. J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):511-516.

37 DeLambo K.E., Ievers-Landis C.E., Drotar D., Quittner A.L. Association of observed family relationship quality and problem-solving skills with treatment adherence in older children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(5):343-353.

38 Fiese B.H., Wamboldt F.S., Anbar R.D. Family asthma management routines: connections to medical adherence and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2005;146(2):171-176.

39 Lewin A.B., Heidgerken A.D., Geffken G.R., Williams L.B., Storch E.A., Gelfand K.M., et al. The relation between family factors and metabolic control: the role of diabetes adherence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(2):174-183.

40 Arafa M.A., Zaher S.R., El-Dowaty A.A., Moneeb D.E. Quality of life among parents of children with heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:91.

41 Alderfer M.A., Labay L.E., Kazak A.E. Brief report: does posttraumatic stress apply to siblings of childhood cancer survivors? J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28(4):281-286.

42 Satchell M., Pati S. Insurance gaps among vulnerable children in the United States, 1999-2001. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1155-1161.

43 Newacheck P.W., Houtrow A.J., Romm D.L., Kuhlthau K.A., Bloom S.R., Van Cleave J.M., et al. The future of health insurance for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e940-e947.

44 Lotstein D.S., Inkelas M., Hays R.D., Halfon N., Brook R. Access to care for youth with special health care needs in the transition to adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):23-29.

45 Thyen U., Kuhlthau K., Perrin J.M. Employment, childcare, and mental health of mothers caring for children assisted by technology. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):1235-1242.

46 Porterfield S.L. Work choices of mothers in families with children with disabilities. J Marriage Family. 2002;64:972-981.

47 Lukemeyer A., Meyers M.K., Smeeding T. Expensive children in poor families: Out-of-pocket expenditures for the care of disabled and chronically ill children in welfare families. J Marriage Family. 2000;62:399-415.

48 Cohen M.H. The technology-dependent child and the socially marginalized family: a provisional framework. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(5):654-668.

49 Feudtner C., Feinstein J.A., Satchell M., Zhao H., Kang T.I. Shifting place of death among children with complex chronic conditions in the United States, 1989-2003. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2725-2732.

50 McIntosh J., Runciman P. Exploring the role of partnership in the home care of children with special health needs: qualitative findings from two service evaluations. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(5):714-726.

51 Leonard B.J., Brust J.D., Nelson R.P. Parental distress: caring for medically fragile children at home. J Pediatr Nurs. 1993;8(1):22-30.

52 Stevens B., Croxford R., McKeever P., Yamada J., Booth M., Daub S., et al. Hospital and home chemotherapy for children with leukemia: a randomized cross-over study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(3):285-292.

53 Leonard B.J., Brust J.D., Sielaff B.H. Determinants of home care nursing hours for technology-assisted children. Public Health Nurs. 1991;8(4):239-244.

54 Teague B.R., Fleming J.W., Castle A., Kiernan B.S., Lobo M.L., Riggs S., et al. “High-tech” home care for children with chronic health conditions: a pilot study. J Pediatr Nurs. 1993;8(4):226-232.

55 Knapp C.A., Shenkman E.A., Marcu M.I., Madden V.L., Terza J.V. Pediatric palliative care: describing hospice users and identifying factors that affect hospice expenditures. J Palliat Med. 2009.

56 Fowler K., Poehling K., Billheimer D., Hamilton R., Wu H., Mulder J., et al. Hospice referral practices for children with cancer: a survey of pediatric oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1099-1104.

57 Dickens D.S. Comparing pediatric deaths with and without hospice support. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010.

58 Feudtner C., DiGiuseppe D.L., Neff J.M. Hospital care for children and young adults in the last year of life: a population-based study. BMC Med. 2003;1:3.

59 Lantos J.D., Berger A.C., Zucker A.R. Do-not-resuscitate orders in a children’s hospital. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(1):52-55.

60 Ashby M.A., Kosky R.J., Laver H.T., Sims E.B. An enquiry into death and dying at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital: a useful model? Med J Aust. 1991;154:165-170.

61 van der Wal M.E., Renfurm L.N., van Vught A.J., Gemke R.J. Circumstances of dying in hospitalized children. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158(7):560-565.

62 McCallum D.E., Byrne P., Bruera E. How children die in hospital. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(6):417-423.

63 Ramnarayan P., Craig F., Petros A., Pierce C. Characteristics of deaths occurring in hospitalised children: changing trends. J Med Ethics. 2007;33(5):255-260.

64 Wolfe J., Hammel J.F., Edwards K.E., Duncan J., Comeau M., Breyer J., et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717-1723.

65 Wolff J., Robert R., Sommerer A., Volz-Fleckenstein M. Impact of a pediatric palliative care program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(2):279-283.

66 MacDonald H., Callery P. Different meanings of respite: a study of parents, nurses and social workers caring for children with complex needs. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(3):279-288. discussion 289

67 Damiani G., Rosenbaum P., Swinton M., Russell D. Frequency and determinants of formal respite service use among caregivers of children with cerebral palsy in Ontario. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(1):77-86.

68 Sutton D., Stanley P., Babl F.E., Phillips F. Preventing or accelerating emergency care for children with complex healthcare needs. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):17-22.

69 Hays R.M., Valentine J., Haynes G., Geyer J.R., Villareale N., McKinstry B., et al. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):716-728.

70 Knapp C.A., Madden V.L., Curtis C.M., Sloyer P.J., Huang I.C., Thompson L.A., et al. Partners in care: together for kids: Florida’s model of pediatric palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(9):1212-1220.

71 Waldfogel J. The Impact of the Family and Medical Leave Act. J Policy Anal Manage. 18(2), 1999.

72 Feudtner C., Noonan K.G. Poorer health: the persistent and protean connections between poverty, social inequality, and child well-being. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(7):668-670.

73 Marston J., Germ R.M., Granera Lopez D.J., Lowe P., Shaw R. Children’s hospice and palliative care worldwide. In: Armstrong-Dailey A., Zarbock S., editors. Hospice care for children. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009:365-377.

74 Sacarlal J., Nhacolo A.Q., Sigauque B., Nhalungo D.A., Abacassamo F., Sacoor C.N., et al. A 10 year study of the cause of death in children under 15 years in Manhica, Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:67.

75 De Baets A.J., Bulterys M., Abrams E.J., Kankassa C., Pazvakavambwa I.E. Care and treatment of HIV-infected children in Africa: issues and challenges at the district hospital level. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(2):163-173.

76 Awqati N.A., Ali M.M., Al-Ward N.J., Majeed F.A., Salman K., Al-Alak M., et al. Causes and differentials of childhood mortality in Iraq. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:40.

77 Cuttini M., Casotto V., de Vonderweid U., Garel M., Kollee L.A., Saracci R. Neonatal end-of-life decisions and bioethical perspectives. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(Suppl 10):S21-S25.

78 Pignotti M.S., Donzelli G. Periviable babies: Italian suggestions for the ethical debate. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(9):595-598.