CHAPTER 111 ENVIRONMENTAL TOXINS AND DISORDERS OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Individual cases of lead poisoning were reported as early as 200 B.C. Nevertheless, the need for the evaluation and treatment of the medical effects caused by exposure to chemicals was not recognized until the 20th century. Many of the offending chemicals affect both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS), and high-level exposure often results in delirium, seizures, or coma.1–4 Although residual effects can include mood and cognitive disorders, they are often not attributed to exposure to these chemicals.

Because the diagnosis of toxin-mediated neurological deficits is one of exclusion, it is important to substantiate a history of significant exposure. Neurological examination and neuroimaging techniques are not very helpful in making a specific diagnosis of toxic encephalopathy but might rule out other causes for the patient’s clinical presentation.5,6 Neuropsychological assessment is essential in the evaluation of these patients. However, decrements in performance on these tests may be erroneously interpreted by clinicians who are not versed in neurobehavioral toxicology. In addition, evaluation of toxic effects on the brain must be considered in the context of each patient’s personality because psychiatric changes can be primary or secondary to chemical exposure.

The clinical manifestations that result from exposure to distinct classes of agents (e.g., metals, organic solvents) are described in this chapter. However, a patient exposed to a certain chemical might not necessarily suffer from all of the symptoms associated with that substance. As with any diagnostic process, the differential diagnosis of neurotoxic exposure, neurological disorders, psychiatric diathesis, or malingering is based on the combined evidence derived from occupational and medical histories; from neurological, psychiatric, and neuropsychological examination findings; and from results of appropriate ancillary studies.

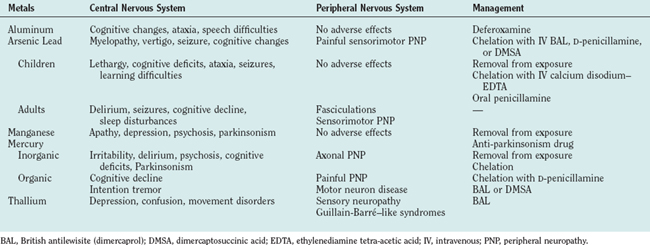

METAL INTOXICATION

Arsenic

Cause and Pathogenesis

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health estimates that about 900,000 workers have potential daily exposure to arsenic. Arsenic poisoning occurs mainly via the oral route. The metal is stored in the liver, kidneys, intestines, spleen, lymph nodes, and bones. After a few days, arsenic is also deposited in hair, where it can stay for many years. Arsenic is excreted slowly in the urine and in the feces, and it takes as long as 2 weeks for a single large dose of the toxin to be excreted. Arsenic affects oxidative metabolism and prevents the transformation of thiamine into acetyl–coenzyme A, rendering patients thiamine deficient. Organic arsenicals release the poison slowly and are therefore less likely to produce acute symptoms than is the elemental metal. Brains of patients who die of arsenic encephalopathy exhibit congestion, hemorrhagic lesions throughout the white matter, and areas of necrosis. Peripheral nerves exhibit decreased numbers of myelinated fibers and degenerative changes, including swelling, granularity, and a reduction in the number of axons.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Acute toxicity is characterized by fever, headaches, anxiety, and vertigo. Seizures are common. Neurological examination reveals nystagmus, increased tendon reflexes, neck stiffness, and sometimes paralysis.7 Mees’ lines (white lines in the nails) usually appear 2 to 3 weeks after acute exposure to arsenic. Encephalopathy with marked excitement followed by lethargy and signs of acute peripheral neuropathy can develop within a few hours. In patients with fatal acute poisoning, coma and death ensue within a few days. Patients with subacute or chronic arsenic encephalitis can suffer from relentless headaches, physical and mental fatigue, vertigo, restlessness, and focal pareses. Spinal cord involvement is associated with weakness, sphincter disturbances, and motor and sensory impairments. Optic neuritis, manifested by cloudy vision and visual field defects, can also occur subacutely or be delayed for years. In general, a mixed sensory and motor neuropathy develops within 7 to 10 days after ingestion of toxic amounts of arsenic, and patients often complain of severe burning sensation in the soles of the feet. Long-standing cognitive changes have been reported.

Arsenic intoxication should be considered in a patient with severe abdominal pain, dermatitis, painful peripheral neuropathy, and seizures. A history of arsenic exposure and toxic arsenic levels in hair, urine, or nails confirm the diagnosis. Arsenic is poorly tolerated in the presence of alcohol. Therefore, patients with alcohol-related disease have a greater risk of developing arsenic neuropathy. Although hair and nail samples may be useful, measurement of urinary arsenic levels is the test of choice. A level of arsenic in urine (24-hour measurement) greater than 50 μg/g creatinine is considered elevated. Because urinary level may be high after ingestion of seafood, a dietary history should be obtained. More reliable values can be obtained by measuring urinary inorganic arsenic metabolites: monomethylarsonic acid and dimethylarsinic acid.

Management

In patients with acute oral ingestion of arsenic, gastric lavage with electrolyte replacement is recommended. Excretion of absorbed arsenic can be enhanced by chelation with dimercaprol (British antilewisite), D-penicillamine, or dimercaptosuccinic acid. Chelating agents can reverse or prevent the attachment of heavy metals to various essential body chemicals (Table 111-1). Although chelating agents may alleviate the acute symptoms, they might not improve chronic symptoms such as peripheral neuropathy or encephalopathy. Dimercaprol treatment is not considered effective after the appearance of neuropathy. Intravenous fluids for dehydration and morphine for abdominal pain are also recommended. Prognosis with severe arsenic poisoning is poor, with a mortality rate of 50% to 75%, usually within the first 48 hours.

Lead

Inorganic Lead

Cause and Pathogenesis

Lead poisoning has a very long history. Although it was identified as early as 200 B.C., it remains a common occurrence even today. More than 1 million workers in more than 100 occupations are exposed to lead. In lead-related industries, workers not only inhale lead dust and lead fumes but may eat, drink, and smoke in or near contaminated areas, increasing the probability of lead ingestion. Family members can also be exposed to lead dust by workers who do not wash thoroughly before returning to their homes. Other sources of lead exposure include surface dust and oils. The de-leading of gasoline has significantly decreased that source of lead exposure. The current major sources of lead in the environment are lead paint in homes built before 1950 and lead used in plumbing, which was restricted in 1986. In 1991, median blood levels of lead in adults in the United States were estimated at 6 μg/dL.8

Children 5 years old or younger are especially vulnerable to the toxic effects of lead. Elevated lead levels in children are caused by pica (compulsive eating of nonfood items) or by the mouthing of items contaminated with lead from paint dust. Children also absorb and retain more lead than do adults. For example, approximately 10% of ingested lead is absorbed by adults whereas 40% to 50% of ingested lead is absorbed by children. Young children with iron deficiency have increased lead absorption. The risk of in utero exposure is high because lead readily crosses the placenta.9

After inorganic lead is absorbed, it binds to erythrocytes and is excreted unchanged in humans. The rate of absorption depends on age and nutritional status. For example, iron and calcium deficiencies cause significant increases in lead absorption. Once absorbed, lead is also distributed to soft tissues (kidney, bone marrow, liver, and brain) and mineralized tissues (bones and teeth); 95% of the total body burden of lead is found in teeth and bones. Pregnancy, menopause, and chronic diseases are associated with mobilization of lead from bones and increased levels in blood. The turnover rate of lead in cortical and trabecular bone is slow, its half-life ranging from years to decades. Lead excretion is through the kidneys or the biliary system into the gastrointestinal tract. Although a person’s blood levels may begin to return to normal after a single exposure, the total body burden of lead may still be elevated. For lead poisoning to occur, significant acute exposures are not necessary because the body accumulates lead over time and releases it slowly.

Lead encephalopathy has been associated with softening and flattening of convolutions in the brain. On occasion, there are punctate hemorrhages, dilation of the vessels, and dilation of the ventricular system, especially in the frontal lobes. Histologically, extensive involvement of the ganglion cells is evident. The developing brain appears to be vulnerable to levels of lead that were once thought to cause no harmful effects.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

In children, exposure to toxic doses of lead can cause listlessness, drowsiness with clumsiness, and ataxia. Very high levels can cause convulsions, respiratory arrest, and coma. A diagnosis of lead toxicity should be considered in a child who shows changes in mental status, gait disorder, or seizures. Chronic low-level exposure in children can result in attention and learning disabilities or in cognitive decline. Children chronically exposed to lead have been reported to show a drop in mean verbal IQ score of 4.5 points. Primary school children with high lead levels in teeth, but without a history of lead exposure, had larger deficits in speech and language processing, psychometric intelligence scores, and classroom performance than did children with lower levels of lead. Children with high lead levels in their teeth are sevenfold more likely not to graduate from high school. They have a greater prevalence of poor eye-hand coordination, reading disabilities, poor fine motor skills, and poor reaction time.9–11

At present, acute lead encephalopathy resulting from industrial exposure is not common. Signs and symptoms generally include delirium, combative irrational behavior, sleep disturbances, decreased libido, increased distractibility, increased irritability, and mental status changes marked by psychomotor slowing, memory dysfunction, and seizures.12

Involvement of both sensory and motor peripheral nerves can be seen in adults with chronic lead intoxication. Sensory complaints include paresthesias and pain. Motor signs include fasciculations, atrophy, and weakness. Severe cases can manifest with wristdrop and footdrop. Extensive bilateral neuropathy involving the fingers, the hands, and the biceps, triceps, and deltoid muscles has also been reported. In individuals with predominantly motor findings, nerve conduction velocity may not be altered even after significant occupational exposure, but mild slowing in nerve conduction velocity has been reported. Anemia, abnormal kidney function, hypertension, and gout can also occur. Miscarriage and stillbirths are common among women who work with lead. Men may suffer from reduced sperm motility and/or counts.

Patients with lead intoxication show increased levels of whole blood lead, free erythrocyte protoporphyrins (FEP), and urinary coproporphyrins. Blood lead levels reflect recent exposure to lead, whereas free erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels reflect chronic exposure. Free erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels begin to rise in adults once blood lead levels reach 30 to 40 μg/dL. These levels may remain elevated for several months even after exposure has ceased. The body burden of lead is measured through diagnostic chelation. Urinary lead excretion is measured after infusion of 1 g of calcium ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA). More than 600 g of lead excreted in the urine over a period of 72 hours is considered an elevated level. A noninvasive method of measuring body lead burden in bone is x-ray fluorescence. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are not useful in making a diagnosis of lead exposure. In some studies, neuropsychological evaluation of workers with lead blood levels below 30 μg/dL has revealed decrements in visuomotor integration, psychomotor speed, short-term visual and verbal memory, and problem-solving skills.

Management

Immediate removal from the sources of exposure and administration of chelating agents are the main lines of defense against lead intoxication. Intravenous infusion of calcium disodium–EDTA, oral administration of succimer (dimercaptosuccinic acid), and chelation with oral D-penicillamine can be used (up to 2 g/day). Multiple chelation cycles might be necessary, and 24 hours of rest between cycles is recommended. Adequate hydration should be maintained because chelating agents can cause renal toxicity and because they can increase circulating levels of lead as a result of their ability to unbind lead from bones. Dimercaptosuccinic acid is reportedly safer than EDTA and D-penicillamine. Common side effects include hypertension and renal problems. Chelation therapy is recommended for children with blood lead levels above 45 μg/dL. Although chelation therapy may reduce symptoms of acute lead poisoning, it might not affect neurological and renal sequelae of acute or chronic lead intoxication. Prevention of lead toxicity in children includes removal of young children from contaminated environments such as houses with peeling paint. Individuals who are occupationally exposed to lead should use mandatory personal protective equipment. Complete recovery of higher cognitive functions may not occur in children with early childhood exposure to lead.

Organic Lead

Organic lead (tetraethyl lead) is used as an antiknock agent in gasoline and jet fuels. Tetraethyl lead is absorbed rapidly by the skin, the lungs, and the gastrointestinal tract. It is converted to triethyl lead, which might be responsible for its toxicity. Because of its highly lipophilic nature, tetraethyl lead passes the blood-brain barrier readily and accumulates in the limbic forebrain, frontal cortex, and hippocampus. Symptoms of acute high-level exposure include delirium, nightmares, irritability, and hallucinations. Chronic effects of tetraethyl lead include poor neurobehavioral scores in tests of manual dexterity, executive ability, and verbal memory. Treatment is mainly supportive.

Manganese

Cause and Pathogenesis

Manganese is found in mining dusts and as an antiknock additive in gasoline.

Hospitalized patients receiving total parenteral nutrition therapy that includes manganese can develop distinctive T1-weighted hyperintense signals in the region of the globus pallidus on magnetic resonance images. Although these changes tend to disappear after cessation of total parenteral nutrition, their presence is correlated with high blood manganese levels and with clinical signs of parkinsonism.

Inhalation is the primary source of manganese exposure. Neuropathologically, affected cells, including neurons in the pallidus, show histopathological changes. Neuronal death has been reported in the substantia nigra, the frontal and parietal cortices, cerebellum, and the hypothalamus.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The onset of manganese toxicity depends on the intensity of exposure and on individual susceptibility. Symptoms may appear as soon as 1 or 2 months or as late as 20 years after exposure. The earliest symptoms of manganism include anorexia, apathy, hypersomnolence, and headaches. Neurobehavioral changes include irritability, emotional lability, and, after continued exposure, psychosis and speech abnormalities that sometimes lead to mutism. Other signs and symptoms include masklike facies, bradykinesia, micrographia, retropulsion and propulsion, fine or coarse tremor of the hands, and gross rhythmical movements of the trunk and head.13

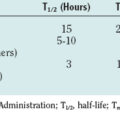

A diagnosis of manganism requires a history of exposure to the toxin. Forty three percent of manganese body burden is in the bone. Excretion is biphasic, and consists of a rapid phase with a half-life of 4 days and a slower phase with a half-life of about a month. Individual manganese levels in blood and urine might not necessarily be correlated with the degree of current or past exposure.

Management and Prognosis

The patient must be removed from the source of exposure. Manganese-induced movement disorders may or may not respond to levodopa. Patients may respond to levodopa doses of more than 3 g/day, with the best effects on rigidity. Chelation therapy may be useful. The neurological syndrome is usually progressive. In the very early stages, signs and symptoms may improve over a period of months after removal of the patient from the source of exposure, but the improvement is not necessarily correlated with a reduction in manganese concentration.

Mercury

Inorganic Mercury

Cause and Pathogenesis

Inorganic mercury compounds have been used as antiseptics, disinfectants, and purgatives. Mercury was also used formerly in the form of cinnabar, a red pigment used for painting and coloring. Metallic mercury becomes volatile at room temperature and enters the body via inhalation. Mercury is a pollutant in air and water. Between 1953 and 1956, an epidemic of methyl mercury poisoning occurred in Japan when a large number of villagers developed chronic mercurialism (Minamata disease) from ingesting fish contaminated with methyl mercury from industrial waste. Individual susceptibility to the toxic effects of mercury varies, depending on the form of mercury involved, hygiene, diet (including vitamin deficiency), and intrinsic differences in mercury metabolism.

Elemental mercury in the plasma is bound to hemoglobin and proteins and is taken up into the brain. Mercury has been detected in the urine as long as 6 years after initial exposure. Although the kidneys are the organs most affected by mercury, the effect on the CNS is substantial, and the highest concentrations are in the brainstem, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and the hippocampus. Inorganic mercury alters cell membranes, but postmortem studies have revealed no or only slight neuronal damage in the presence of intracellular mercury.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Acute mercury poisoning can be caused by accidental ingestion of an antiseptic found in a medicine cabinet. Affected patients suffer from irritable, hyperactive, psychotic behaviors. Patients might develop acute weakness in the lower extremities. Chronic mercury toxicity is also associated with progressive personality changes, together with tremor and weakness of the limbs. Mercury-induced tremors, also known as “hatter’s shakes” or “Danbury shakes,” consist of fine tremors that occur at rest and are interrupted by myoclonic jerks. Patients might also develop gait and balance difficulties. Parkinsonism, dyskinetic movements, and seizures have been reported. Mercury poisoning may also be accompanied by peripheral polyneuropathy (sensorimotor axonopathy) that affects mainly the lower extremities. These are characterized by painful paresthesias and muscle atrophy. Blurred vision, narrowing of the visual fields, optic neuritis, optic atrophy, nystagmus, vertigo, and sensory ataxia have also been observed. Personality and cognitive changes might become manifest before the appearance of other neurological signs. “Mercurial neurasthenia,” which consists of extreme fatigue, hyperirritability, insomnia, pathological shyness, and depression, may develop weeks or months before the patient seeks treatment. In addition, violence and homicidal behaviors have been reported.

Acrodynia, as chronic mercury toxicity in children used to be called, is a syndrome characterized by painful neuropathy and autonomic changes. This syndrome includes redness and coldness of hands and feet, painful limbs, profuse sweating of the trunk, severe constipation, and weakness. Affected children may also suffer from personality and cognitive changes and from tremors similar to those found in adults.

Serum concentrations of mercury are not reliable indicators of inorganic or organic mercury toxicity because blood levels vary greatly between individuals. The threshold biological exposure indexes are 15 μg/L for blood and 35 μg/g of creatine for urine. Urinary excretion is not a good measure of toxicity because there is no correlation between symptoms and amount of mercury excreted in the urine. Because the signs of mercury intoxication mimic those of common neurological syndromes such as parkinsonism, the correct diagnosis depends on occupational history and documentation of mercury in the patient’s blood, urine, or hair.

Management and Prognosis

Removal of the patient from the sources of exposure and chelation with N-acetyl-D-penicillamine are recommended. Long-term computed tomographic follow-up of survivors of Minamata disease revealed decreased bilateral attenuation in the visual cortex and diffuse atrophy of the cerebellum, especially the vermis.13a

Organic Mercury

Cause and Pathogenesis

Intoxications can be caused by ingestion of fish containing methyl mercury, homemade bread prepared from seed treated with methyl mercury–containing fungicide, or meat from livestock fed grain treated with mercury-containing fungicides. Organic mercury is absorbed via the gastrointestinal tract and is slowly excreted through the kidneys; the half-life ranges from 40 to 105 days. Mercury readily crosses the placenta, and the blood concentrations in the fetus are equal to or greater than those in the maternal blood. Fetal methyl mercury poisoning can occur in asymptomatic mothers. Because methyl mercury can also be secreted in breast milk, mercury poisoning can also occur in breastfed children.

Organic mercury readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, and its turnover in the brain is slow. In cases of chronic exposure, approximately 10% of the body burden localizes in the brain. Less than 3% is degraded into inorganic mercury. Excretion occurs primarily through the gastrointestinal tract, mostly through biliary secretion, and the mercury then undergoes immediate gastrointestinal reabsorption into the blood stream. Neuropathological changes included damage to peripheral neurons in the myelin sheath accompanied by glial proliferation and phagocytosis. In the brain, the most severe damage was found in the primary visual cortex, followed by the cerebellar cortex, the precentral and postcentral gyri, the transverse gyrus, and the putamen.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Organic mercury toxicity manifests as a triad of peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, and cortical blindness. There may be a delay of 2 weeks to several months before the appearance of symptoms after exposure to the toxin. These begin with paresthesias of the extremities, which extends to a glove-stocking distribution. Touch and pain sensations are impaired, and there is often constriction of the visual fields.

Infants of intoxicated mothers may develop mental retardation and cerebral palsy. Motor neuron disease resembling amyotrophic lateral sclerosis can also occur. In these patients, gradual weakness develops with features of both upper motor neuron disease (increased reflexes and prominent jaw jerk) and lower motor neuron disease (fasciculations and atrophy).

Diagnostic approaches should include measurements of mercury in blood and hair because these values are less variable than urinary levels. Hair samples must be taken close to the scalp and then washed to remove contaminants such as hair dyes. Hair samples provide information about mercury exposure during the previous year.

Management and Prognosis

The patient should be removed from the source of exposure. Chelating agents such as D-penicillamine, dimercaprol, or dimercaptosuccinic acid, which accelerate the excretion of mercury, are also useful. Because chelation mobilizes mercury from bones, it may exacerbate clinical symptoms and cause deposits of mercury in the brain. D-Penicillamine is effective in improving the CNS effects of mercury. However, D-penicillamine can cause hematopoietic suppression, alterations in cognitive and renal function, symptoms of myasthenia gravis, hepatitis, and allergic reactions. Blood concentrations of mercury usually begin to decline 3 days after initiation of chelation therapy. Administration of selenium and vitamin E may prevent the development of symptoms in asymptomatic subjects with high levels of blood mercury.

Most patients with severe mercury poisoning die within a few weeks of the appearance of clinical manifestations. Those who survive may have major neurological disability. Patients with mild or moderate neurological signs and symptoms may experience improvement within the first 6 months. In a few cases, bedridden individuals have been reported to regain their ability to walk. Some affected children have regained vision.

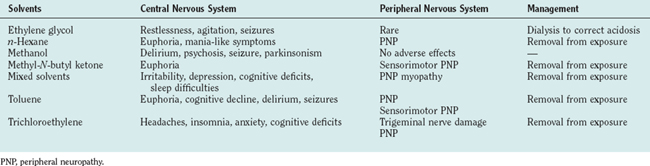

ORGANIC SOLVENTS (Table 111-2)

Ethylene Glycol

Antifreeze is the most common source of ethylene glycol. Ingestion of ethylene glycol can be fatal and accounts for about 40 to 60 deaths per year. The toxicity of ethylene glycol is caused by its metabolic products: oxalate and aldehydes. Death results from renal or cardiopulmonary failure. After ingestion, signs and symptoms usually occur rapidly and include restlessness and agitation, increased somnolence, and convulsions. Stupor and coma can also occur. Milder cases are associated with fatigue, personality changes, and depression. The possibility of ethylene glycol poisoning is suggested by apparent inebriation in a patient whose breath does not smell of alcohol. Neuropathological abnormalities include cerebral edema and hemorrhage. Treatment consists of correcting the acidosis and using early dialysis to remove ethylene glycol, oxalate, and aldehydes.

n-Hexane and Methyl-N-Butyl Ketone

Exposure to n-hexane occurs from recreational use. Acute exposure to n-hexane causes euphoria, but chronic intoxication is associated with peripheral neuropathy. n-Hexane is metabolized to 2,5-hexanedione, which is responsible for much of the neurotoxicity of the parent compound.

n-Hexane does not produce significant CNS symptoms. Lightheadedness, headache, decreased appetite, mild euphoria, and occasional hallucinations may occur acutely, but n-hexane does not cause seizures or delirium. The predominant neurological consequence of n-hexane exposure is peripheral neuropathy. Symmetrical sensory dysfunction in the hands and feet is the usual presenting complaint. There is decreased sensation to pinprick, vibration, and thermal stimulation. Persons who sniff glue (“huffers”) may develop proximal weakness. The most prominent electrophysiological feature is slowing of motor and nerve conduction velocities, which is proportional to the severity of clinical disease.

Methyl-N-butyl ketone is used as a paint thinner, cleaning agent, and solvent for dye printing. Exposure to this solvent is associated with sensorimotor polyneuropathy, which may begin several months after a period of continued exposure. In the later stages, axonal degeneration occurs distally.

Treatment for n-hexane and methyl-N-butyl ketone neuropathy consists of removal from the source of exposure. Recovery (regeneration of peripheral nerve axons) may then occur over a period of weeks.

Methyl Alcohol

Methyl alcohol (methanol, wood alcohol) is used as a solvent and is a component of antifreeze fluids. Although only mildly toxic, methanol is oxidized to formaldehyde and formic acid, which can produce severe acidosis and are responsible for the clinical symptoms associated with its abuse. The oxidation and excretion of methyl alcohol are slow; toxic symptoms develop over 12 to 48 hours. Methanol toxicity involves the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, the visual system, and the CNS. Toxicity is manifested by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, and vertigo. Patients may also become restless, uncoordinated, weak, or delirious. More severe cases can manifest with visual loss, parkinsonism, convulsions, stupor, or coma. Death can also occur as a result of respiratory failure. Methanol-induced neuropathological abnormalities include neuronal degeneration, primarily in the parietal cortex.14

Treatment involves frequent measurements of blood methanol and correction of acid-base imbalance. Administration of ethyl alcohol may be used to retard the conversion of methanol into formaldehyde and formic acid. Folic acid may be used to accelerate the metabolism of formic acid to carbon dioxide. Peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis is recommended for patients with methanol blood levels greater than 50 mg.

Mixed Solvents

Cause and Pathogenesis

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health estimates that 9.8 million workers were exposed to solvents in the United States in 1970. The respiratory system is the primary mode of solvent absorption because of their volatility. The amount absorbed is influenced by respiratory rate, use of gas masks, and adequacy of workplace ventilation. At present, it appears that the number of workers suffering adverse effects from exposure to organic solvents has decreased because of closer adherence to rules establishing appropriate levels of safe airborne concentrations and because of the mandatory use of personal protective equipment. However, recreational solvent huffing remains a major public health problem. In these cases, substances such as paint, glue, and gasoline in plastic bags are placed over the face and inhaled in order to generate euphoria or a “high.”

Organic solvents are volatile and lipophilic and are eliminated through the kidneys after osmotic conversions that render them more water soluble. However, the metabolites that result from these reactions may be more toxic than the original compounds. Paint huffers can suffer from acute peripheral neuropathy. They can also suffer from frontal lobe atrophy. Although solvents may act like anesthetics (e.g., trichloroethylene), convulsants (e.g., flurothyl), anticonvulsants (e.g., toluene), anxiolytics (e.g., toluene), antidepressants (e.g., benzyl chloride), and narcotics (e.g., trichloroethylene), the cellular and molecular bases of their toxic effects remain to be determined. It has been suggested that their adverse effects may be mediated through their actions on neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and γ-aminobutyric acid; on receptors; or on ion channels.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Symptoms of acute high-level exposure include euphoria, dysphoria, excitation, exhilaration, headache, and dizziness. Very high levels of exposure that occur during paint huffing may induce somnolence and coma, followed by death. Chronic low-level exposure occurs in industrial settings. In these cases, symptoms develop insidiously. Headaches are the most commonly reported problem. These begin shortly after patients arrive at work and disappear outside work hours and during vacations, when patients are not in the vicinity of the organic solvents. Other complaints include irritability, depression, poor attention or concentration, memory loss, sleep difficulties, decreased libido, and pain and numbness starting in the feet and progressing to the hands. Activities mandating manual dexterity, executive functioning, or motor functioning can be severely affected.

The presence of a positive exposure history, objective findings on neuropsychological tests, and neurological examination findings suggestive of polyneuropathy are indicators of a solvent-induced neurological syndrome. The diagnosis is often one of exclusion because there are no specific biomarkers of solvent exposure. The differential diagnosis includes other neurological conditions, heavy alcohol abuse, and primary neuropsychiatric disorders with similar manifestations.

A rating scale was developed in 1985 to classify patients who had been exposed to solvents:

Type I: subjective nonspecific symptoms only. Patients complain of fatigue, attention and memory difficulties, and changes in mood and sleep patterns without any objective evidence of neurobehavioral dysfunctions. After discontinuation of exposure, symptoms completely disappear within 6 months to 1 year.

Type I: subjective nonspecific symptoms only. Patients complain of fatigue, attention and memory difficulties, and changes in mood and sleep patterns without any objective evidence of neurobehavioral dysfunctions. After discontinuation of exposure, symptoms completely disappear within 6 months to 1 year. Type IIa: sustained personality and mood changes. Affective changes including depression, fatigue, poor impulse control, and aggressiveness. There is no evidence of neurobehavioral abnormalities.

Type IIa: sustained personality and mood changes. Affective changes including depression, fatigue, poor impulse control, and aggressiveness. There is no evidence of neurobehavioral abnormalities. Type IIb: impairment of intellectual function, documented by objective neurobehavioral tests, with possible mild neurological abnormalities. Difficulty in concentration, memory loss, and a decline in learning capacity may be present. After the patient’s removal from exposure, these symptoms may remain stable or improve but should not become worse.

Type IIb: impairment of intellectual function, documented by objective neurobehavioral tests, with possible mild neurological abnormalities. Difficulty in concentration, memory loss, and a decline in learning capacity may be present. After the patient’s removal from exposure, these symptoms may remain stable or improve but should not become worse. Type III: dementia, with neurological signs and/or neuroradiological findings. Results of neurobehavioral tests reveal abnormalities related to repeated severe exposure (e.g., paint huffing). Symptoms are rarely reversible but do not generally progress once exposure is stopped.

Type III: dementia, with neurological signs and/or neuroradiological findings. Results of neurobehavioral tests reveal abnormalities related to repeated severe exposure (e.g., paint huffing). Symptoms are rarely reversible but do not generally progress once exposure is stopped.

Nerve conduction studies can be extremely useful because many organic solvents affect the PNS before the CNS. Sensory polyneuropathy, more pronounced in the feet than in the hands, is characteristic of exposure to chronic organic solvents.

Management and Prognosis

Management consists of removal from the source of exposure. In addition, anxiety and depression can be treated with psychotherapy or pharmacological interventions. Once the patient is removed from the source of exposure, signs and symptoms remain stable or improve with time. Deterioration may be seen in patients who suffer psychological disorders as a result of their exposure to these organic solvents.

Toluene (Methyl Benzene)

Toluene is a used as paint, lacquer thinner, or a dyeing agent. It is also found in fuels. Because toluene is also part of the glue used by paint huffers, it has been suggested as a potential cause of the neurotoxic syndrome observed in these individuals. Although similar to the neurobehavioral changes of benzene-induced toxic effects, those of toluene toxicity are more severe. Acute exposure causes fatigue, mild confusion, ataxia, and dizziness. Chronic use is associated with euphoria, disinhibition, and tremor. Neurobehavioral effects include decreases in performance IQ, memory abnormalities, poor motor control, decreased visuospatial functioning, and dementia.15 Treatment consists of removal from the source of toluene exposure.

Trichloroethylene

Trichloroethylene is used in dry cleaning. It is also used to degrease metal parts and extract oils and fats from vegetable products. Addiction to the fumes has been reported in workers who experience euphoria upon exposure. Trichloroethylene-induced bronchial constriction, pulmonary edema, and myocardial irritation can result in fatalities. Trichloroethylene exposure can also cause cranial and peripheral neuropathies. Mixed sensory and motor involvements of the trigeminal and facial nerves are observed after high-level trichloroethylene exposure. Exposed individuals can suffer from retrobulbar neuropathy, optic atrophy, and oculomotor disturbances. Peripheral neuropathy is also common and characterized by extensive myelin and axonal degeneration. A history of possible trichloroethylene exposure should be sought in any patient who presents with trigeminal neuralgia or dysfunction. Other symptoms include anxiety, fatigue, headaches, and dizziness, in association with alcohol intolerance. Neurobehavioral effects include poor concentration and memory, decreased manual dexterity and visuospatial accuracy, and slowed reaction times. Treatment involves removal from exposure.

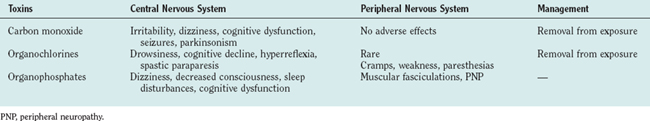

GASES (Table 111-3)

Carbon Monoxide

Cause and Pathogenesis

Carbon monoxide is an odorless, nonirritating gas that is responsible for more than 3000 accidental or suicidal deaths and 10,000 episodes of illness each year. Sources of exposure include portable kerosene heaters, hot water heaters, furnaces, and inadequately vented fireplaces. Automobile exhaust fumes have carbon monoxide concentrations of approximately 50,000 ppm. The threshold limit value of carbon monoxide is 50 ppm, which causes a carboxyhemoglobin saturation level of 8% to 10% after an 8-hour exposure. Carboxyhemoglobin saturation levels of more than 50% cause substantial morbidity, and levels of 70% to 75% are usually fatal. Saturation may be reached because of acute high-level exposure or prolonged exposure to lower concentrations. Carbon monoxide enters the blood stream via the lungs and then binds reversibly to hemoglobin. Because the affinity of hemoglobin for carbon monoxide is about 225 times greater than that for oxygen, exposure to carbon monoxide results in decreased capacity of red blood cells to carry oxygen.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Neurological signs of mild carbon monoxide poisoning include headache, dizziness, and impaired vision, which can progress to convulsions and coma. Persistent chronic exposure from inadequately vented heaters in the home can cause blindness, deafness, pyramidal signs, extrapyramidal signs, and convulsive disorders.

Mild neurological effects may be transient or persistent and may appear immediately or days to weeks after exposure. Neuropsychiatric changes include irritability, violent behavior, euphoria, confusion, and impaired judgment. Cognitive symptoms include difficulties with visual and verbal memory, spatial deficits, and decline in cognitive efficiency and flexibility.16 Parkinsonism has also been reported after acute and chronic exposure. Imaging studies reveal lucency in the globus pallidus and atrophy.

A history of exposure to carbon monoxide is necessary to make the diagnosis. In suspected cases, blood levels of carboxyhemoglobin should be determined, even though the current level of carbon monoxide in the blood may not be indicative of the severity of poisoning because carboxyhemoglobin declines rapidly after removal from exposure. If a patient dies of carbon monoxide poisoning, the level of carboxyhemoglobin determined in postmortem study represents the actual level of carbon monoxide at the moment of death, inasmuch as carbon monoxide cannot be excreted without active respiration.

Management and Prognosis

Treatment involves removal of the patient from the contaminated environment and administration of 100% oxygen. Hyperbaric oxygen reduces the half-life of carboxyhemoglobin to less than 25 minutes and is considered the treatment of choice for all patients with severe carbon monoxide intoxication, although CNS oxygen toxicity is a potential risk. Hypothermia has also been advocated to decrease the tissue demands of oxygen.

Neurological sequelae, including cortical blindness, seizures, cognitive impairment with amnesia, polyneuropathy, and a parkinsonian syndrome have been reported. Prognosis after intoxication can vary. For example, a follow-up study performed 3 years after carbon monoxide poisoning revealed that 43% of patients had impaired memory, 33% evinced a deterioration of personality, and 13% had neuropsychiatric abnormalities.

PESTICIDES (See Table 111-3)

Organochlorine Insecticides

Cause and Pathogenesis

Chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides are fat soluble. They can last for a long time in the environment and contribute to long-term clinical toxicity. These organochlorine insecticides include aldrin, chlordane, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), endrin, heptachlor, chlordecone (Kepone), and lindane.17 Most of them have been banned or restricted in the United States because of their deleterious effects on wildlife. However, some are still used in less industrialized countries. Absorption may occur through oral, respiratory, or dermal routes.

Although the mechanisms responsible for the neurotoxic effects of DDT and other organochlorine insecticides remain to be fully clarified, they are thought to involve excessive acetylcholine release. In contrast, organophosphates block the extracellular metabolism of acetylcholine. Because exposure to both organochlorines and organophosphates results in cholinergic overactivation, they often cause similar clinical pictures.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Acute DDT toxicity is associated with variable hyperesthesias in the mouth, tongue, and lower part of the face. Patients complain of dryness of the mouth, a gritty sensation in the eyelids, and marked drowsiness. Other signs and symptoms include night blindness, stiffness and pain in the jaw, aching of the limbs, spasms, and tremors. Neurological examination reveals that patients can suffer from nystagmus, variable disturbances to touch and heat in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve, upper extremity weakness that can progress to wristdrop, and inability to stand on one leg for any length of time. Electroencephalographic abnormalities include bitemporal sharp-wave activity and shifting lateralization. The diagnosis is one of exclusion, which depends mainly on the history of exposure.

Organophosphate Insecticides

Cause and Pathogenesis

Organophosphates are absorbed through the dermal and respiratory routes, but small amounts may also be ingested with foods that have been sprayed. Organophosphate insecticides are highly toxic to insects but less so to humans and domestic animals.18 Organophosphates such as triorthocresyl phosphate, mipafox, and trichlorfon compounds can be neurotoxic. Persons at high risk for organophosphate poisoning include factory workers involved in the production of these compounds and agricultural workers who use them to spray crops. Epidemics of organophosphate poisoning have been reported in some developing countries. In 1987, there were reports of 1754 pesticide-related cases in California.

Organophosphates inhibit acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase. They include chlorpyrifos (Dursban), diazinon, malathion, ethyl and methyl parathion, and trichlorfon. The neurotoxicity of these compounds is related to their ability to inhibit acetylcholinesterase, which is found in the brain, spinal cord, myoneural junctions, and parasympathetic and sympathetic synapses. The resulting increase in acetylcholine overstimulates cholinergic receptors located in various anatomical sites.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Affected patients often complain of a vague sense of fatigue, increased salivation, nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, abdominal cramps, headaches, and dizziness. Symptoms develop within 24 hours of exposure. Difficulty with speaking or swallowing, shortness of breath, and muscle fasciculations can be seen in patients with moderate levels of exposure. More severely affected patients have depressed levels of consciousness and marked myosis with no pupillary response. After initial recovery from acute intoxication, a delayed polyneuropathy (organophosphate insecticide delayed polyneuropathy [OPIDP]) may develop. OPIDP is a distal dying-back axonopathy characterized by cramping muscle pain in the legs, paresthesias, and motor weakness beginning 10 days to 3 weeks after the initial exposure. OPIDP-associated signs include footdrop, weakness of intrinsic hand muscles, absence of ankle jerk reflexes, and weakness of hip and knee flexors. Chronic low-level exposure is associated with weakness, malaise, headache, and lightheadedness. Anxiety, irritability, altered sleep, tremor, numbness and tingling of the extremities, and miosis may also be observed.19 Cognitive abnormalities include decreased capacity for information processing, decreased memory and learning abilities, and poor visuoconstructional skills.

Diagnosis depends on exposure history, clinical symptoms, and abnormally low cholinesterase activity in the blood (biological exposure index, 70% of baseline level). A rise in serial cholinesterase levels after removal from exposure is diagnostic. Fasciculations with miosis are also diagnostic of organophosphate poisoning.

Management and Prognosis

At the time of ingestion, vomiting should be induced. The primary treatment for mild to moderate organophosphate poisoning is the administration of atropine sulfate, 1 mg intravenously or intramuscularly, and pralidoxime (Protopam, 2-PAM), 1 g intravenously. Potential complications of atropine toxicity include flushed, hot, and dry skin; fever; and delirium. Pralidoxime may cause marked increases in blood pressure. In patients with very severe organophosphate poisoning, intravenous administration of pralidoxime restores consciousness within 40 minutes. Prolonged high exposure and the appearance of CNS and PNS symptoms may be associated with an incomplete recovery. However, recovery is complete within weeks to months after lower levels of exposure.

ANIMAL TOXINS

Snake, Scorpion, and Spider Venoms

Cause and Pathogenesis

Poisonous snakes include vipers, rattlesnakes, cobras, kraits, mambas, and the American coral snake.20,21 The black widow probably accounts for most of the neurotoxic syndromes that occur after spider bites. Fatalities associated with spider bites occur in approximately 2.5% to 6% of cases.

Animal neurotoxins can either enhance or block cholinergic function. Snake venoms are toxic to cardiac muscles, coagulant pathways, and the nervous system. Snake venom acts presynaptically to inhibit the release of acetylcholine from presynaptic terminals in the neuromuscular junction and cause nondepolarizing neuromuscular block postsynaptically. These actions result in depression of cholinergic function at the neuromuscular junction. In contrast, spider venom causes excessive release of acetylcholine, with resulting tetanic spasms followed by paralysis.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Affected patients can present with retinal hemorrhages, localized pain and swelling, headache, vomiting, loss of consciousness, paresthesias, ptosis, and loss of vision secondary to coagulation disturbances. These signs and symptoms develop between 1 and 10 hours after a bite. Signs of paralysis begin with difficulty swallowing and opening the mouth. Effects of scorpion stings may include both local and systemic complications. Early problems include pain, swelling, excessive salivation, sweating, and abdominal pain. Death may result from hypertension, peripheral circulatory collapse, or cardiac failure. Neurological symptoms are more common in children than in adults and include overexcitement, muscle rigidity, convulsions, and altered mental status, probably secondary to hypoxia. Spider bites can cause paresthesias, fasciculations, tremor, and hyperreflexia. In patients with snake bites, it is especially important to identify the specific snake involved because there are specific antivenins.

Management and Prognosis

Treatment of snake bites involves administration of anticholinesterases and specific antivenin as early as possible after the bite. If these are administered before the development of major weakness, both presynaptic and postsynaptic toxic effects can be aborted. Mechanical respiration may also be necessary. Gradual recovery might occur over the next 2 days. Treatment of scorpion bites depends primarily on supportive respiratory and cardiac measures and treatment of coagulation abnormalities.

Tick Paralysis

Tick paralysis is a flaccid ascending paralysis caused by the bite of certain female ticks—namely, Dermacentor andersoni, Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor occidentalis, Amblyomma americanum, and Amblyomma maculatum—that are found commonly in areas west of the Rocky Mountains. The causative toxin is excreted in the saliva of the mature female tick during engorgement. Small children who are bitten are particularly likely to become paralyzed. The head and neck are the most common sites of tick attachment, although any part of the body may be involved. Proximity of the site of attachment to the brain appears to influence the severity of the disease. The toxin acts by inhibiting acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction, including neurons of the spinal cord and brainstem. The course of tick paralysis depends on the interval between identification and removal of the tick. If removal occurs before bulbar symptoms begin, improvement appears within hours, and complete recovery occurs by 1 week. If bulbar symptoms have appeared, patients usually die despite intensive treatment.

PLANT TOXINS

Chickpea (Lathyrism)

Lathyrism is related to a neurotoxin that acts on glutaminergic system. Spastic paraplegia has been observed in Europe and India after consumption of different varieties of chickpea.22 Development of human lathyrism is associated with two potent neurotoxins found in the peas: α-amino-β-oxalylaminopropionic acid and α-amino-γ-oxalylaminobutyric acid. Toxic neurological signs are seen when 30% or more of the diet consists of chickpeas. Men tend to be affected more than are women. The onset is subtle, with pain in the lumbar region and with stiffness and weakness of the lower extremities on awakening in the morning. The legs may become spastic and exhibit clonic tremor. Other patients complain of tremulousness, numbness, paresthesias, formication, and sphincteric spasms. Some patients complain of pain and cramps in the calf muscles. The upper extremities may also be involved in patients with severe disease. The pain and paresthesias usually disappear within 1 to 2 weeks after chickpeas are removed from the diet, but relapses may occur. Lathyrism has been classified on a 4-point scale: no-stick (mild), one-stick (moderate), two-stick (severe), and crawler-stage (very severe) cases. In the latter cases, victims are unable to move their legs and depend on their arms to move the body on their rumps. Neurological examination reveals no involvement of the cranial nerves, the sensory system, or the cerebellum.

Mushrooms

Amanita mushrooms have strong anticholinergic effects. They contain high concentrations of ibotenic acid, muscazone, and muscimol. Intoxication is associated with mydriasis, agitation, ataxia, muscle spasms, and seizures. Indole compounds may be responsible for mushroom-induced hallucinations. The genera Inocybe and Clitocybe contain muscarine and cause cholinergic excitation at all parasympathetic nerve endings except those of the neuromuscular junctions and nicotinic sites. Coprinus atramentarius, or Inky Cap, is a common mushroom often considered edible. Its consumption in combination with alcohol, however, results in a severe toxic reaction similar to that seen with disulfiram. The syndrome includes facial flushing, paresthesias, and severe nausea and vomiting. The responsible toxin is coprine, which increases acetaldehyde blood levels.

BACTERIAL TOXINS

Botulism

Cause and Pathogenesis

There are approximately 20 cases of foodborne botulism in adults and 250 cases of infantile botulism reported each year. Botulism is thought to be involved in some cases of sudden infant death syndrome because of similar age distribution and because 10 infants who died from sudden infant death syndrome in California in 1977 also had evidence of intestinal infection with Clostridium botulinum. Sudden infant death syndrome might result from infection with C. botulinum because of toxin-induced flaccidity of the upper airway or tongue muscles, which leads to airway obstruction during sleep.

Botulism results from the ingestion of one of the most potent poisons in existence.23 The toxin made by the spores of C. botulinum is a potent inhibitor of acetylcholine release. Three distinct forms of botulism exist. Foodborne botulism occurs after the ingestion of contaminated home-canned fruits and vegetables, which contain already-formed spores. This syndrome appears rapidly, usually between 8 and 36 hours after ingestion. Neurological signs appear within hours or, at most, 1 week after ingestion of the toxin. Wound-induced botulism results from the entry of the organism into the blood stream through the wound site. Spores may germinate locally in the tissues and cause a toxic syndrome. Infantile botulism usually occurs in the first 6 months after birth.24,25 It is caused by the absorption of C. botulinum from the gastrointestinal tract.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Early signs of toxicity include nausea, vomiting with abdominal pain, and diarrhea. The presence of ptosis, extraocular paresis, and progressive weakness is suggestive of the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. In addition, patients may suffer from dryness of the mucous membranes, dysphasia, swallowing difficulties, speech impairment, absence of or decreased gag reflex, and absence of or decreased deep tendon reflexes. By the second to fourth day of illness, greater muscular weakness develops. Progressive muscular weakness of neck muscles can result in inability of patients to raise their heads. Breathing difficulty may also lead to respiratory failure. Infants suffer from weakness with loss of muscle tone.

Botulism is distinguishable from the Guillain-Barré syndrome because it is associated with descending weakness of the limbs, in that proximal muscles are affected before distal ones. Pupillary dilation observed in botulism helps differentiate it from myasthenia gravis.

The diagnosis is confirmed by detecting the toxin either in the patient (blood) or in the implicated food products.26 A stool culture is also recommended.

Management and Prognosis

Trivalent botulism equine antitoxin (ABE) is recommended, and the patient’s respiratory status should be monitored closely. In severe cases, a rapid deteriorating course often ends in death. Death occurs in 70% of untreated cases. If the patient survives, recovery begins within a few weeks.

Diphtheria

Cause and Pathogenesis

Diphtheria is rare in many parts of the world as a result of immunization. Potential risk factors for this disease are lack of immunization, crowding, and poor hygiene. In the United States, only five cases of diphtheria were reported in 1991.

The bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae is the causative agent of diphtheria. It is acquired through respiratory droplets from infected persons or asymptomatic carriers. There are two forms, oropharyngeal and cutaneous, with incubation periods lasting 1 to 4 days. The bacterium affects the respiratory tract, heart, kidneys, and nervous system through a toxin that causes tissue damage in the vicinity of affected areas and is transported to other organs via the blood stream. Muscle and myelin are preferentially affected by this powerful toxin. Neurological symptoms result either from direct damage to muscle and peripheral nerve or from indirect damage caused by hypoxia and airway obstruction. The CNS is not directly affected because the toxin does not cross the blood-brain barrier.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The initial symptoms of the disorder include fever, a gray to black throat membrane that is sore, nasal voice, dysphasia, and regurgitation. Subsequently, trigeminal, facial, vagus, and hypoglossal cranial nerves may become affected. Half of the patients with diphtheria-associated neurological dysfunction suffer from ocular involvement and paralysis of accommodation during the second or third week of disease. Two forms of neuropathy are usually recognized after infections: a localized pharyngeal-extraocular neuropathy secondary to local spread of the bacterial toxin and a generalized polyneuropathy caused by systemic spread of the toxin. Sometimes, patients may also suffer from changes in mental status, from drowsiness, and possibly from convulsions.

The diagnosis is based on clinical history and manifestation. Physical examination reveals a characteristic gray to black membrane in the throat, enlarged lymph glands, and swelling of the neck and larynx. Diphtheric polyneuropathy can be distinguished from other polyneuropathies because of the early bulbar involvement, ciliary paralysis, and subacute evolution of a delayed symmetrical sensorimotor peripheral polyneuropathy. Diagnostic testing includes Gram stain of the infected membrane, throat culture, and electrocardiography, which reveals evidence of myocarditis.

Management and Prognosis

Treatment generally involves administration of antitoxin within 48 hours of the earliest signs of infection; rest; and maintenance of proper airway and cardiac function. Everybody who has had contact of the infected person should be immunized, because protective immunity is not present longer than 10 years after the last vaccination. Diphtheria is preventable through immunization at the age of 3 months. Booster doses at 1 year and before entrance in school are recommended. The rate of death from the disease is 10%. Patients who do not die of respiratory distress or cardiac failure usually stabilize and recover completely over time.

Tetanus

Cause and Pathogenesis

Tetanus is still an important cause of morbidity and mortality in underdeveloped countries. The bacteria can be transmitted in the anaerobic environment of soil-contaminated wounds. Tetanus is seen only in adults who have not been immunized. About 50 to 100 cases are reported in the United States each year, and about 60% of these occur in elderly individuals.

The tetanus toxin is synthesized by the bacillus Clostridium tetani. Spores can remain dormant in the soil or in animal excrements for years until they enter the body and synthesize the neurotoxin. The tetanus toxoid can affect the CNS, the PNS, and the musculature. At high concentrations, the tetanus toxin acts like botulinum toxin in that it inhibits the release of acetylcholine at cholinergic synapses. The nervous system is affected by tetanus through retrograde axonal transport. The incubation period varies from a few hours to several days. If the illness lasts for more than 5 days, demyelination and gliosis may occur, and hemorrhages are evident in the most severe cases.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Patients usually present with headaches, restlessness, and pain at the site of injury. Tightness in the jaw and mild stiffness and soreness in the neck are usually noticed within a few hours. As time progresses, the jaw becomes stiffer and tighter (lockjaw). There is subsequent involvement of throat and facial muscles. Muscle rigidity then becomes generalized and may include the trunk and extremities. Rigidity in the abdominal muscles causes forward arching of the back. Tetanic contractions occur periodically and cause severe pain. In the most severe cases, convulsions and marked dyspnea with cyanosis can occur, terminating in asphyxia and death. Patients may also suffer from anxiety as well as mental and physical agony. The diagnosis depends on a history of a prior wound, a high C. tetani titer, and a history of partial immunization. Tetanus must be differentiated from the stiff-person syndrome, which does not involve trismus.

Management and Prognosis

Patients should be hospitalized. The infected wound should undergo débridement. Barbiturates and diazepam may be used to initiate muscle relaxation. Tetanus immunoglobulin should be given. One dose of 3000 to 6000 U given intramuscularly into three sites simultaneously is recommended. If human antitoxin is unavailable, equine antiserum can be given. Tetanus is prevented by immunization. Children should be immunized at 2 months to 6 years of age. In adults, tetanus boosters last approximately 10 years. The rate of fatality from the disease is about 65%. Death generally occurs rapidly between the third and fifth day of illness. This is caused by exhaustion, spasm-induced asphyxia, or circulatory failure. On occasion, tetanus antitoxin can cause adverse reaction involving primarily the PNS. This is followed by complete recovery after 6 months.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thanks Maryann Carrigan for her assistance in the preparation of this chapter.

Branchi I, Capone F, Alleva E, et al. Polybrominated dephenyl ethers: neurobehavioral effects following developmental exposure. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:449-462.

Davidson PW, Weiss B, Myers GJ, et al. Evaluation of techniques for assessing neurobehavioral development in children. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21:957-972.

Josko D. Botulin toxin: a weapon in terrorism. Clin Lab Sci. 2004;17:30-34.

Levy BS, Nassetts WJ. Neurologic effects of manganese in humans: a review. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2003;9:153-163.

Rhee P, Nunley MK, Demetriades D, et al. Tetanus and trauma: a review and recommendations. J Trauma. 2005;58:1082-1088.

1 Goetz CG. Neurotoxins in Clinical Practice. New York: Spectrum, 1985.

2 Carpenter DO. Effects of metal on the nervous system of humans and animals. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2001;14:209-218.

3 Chang LW, Dyer RS, editors. Handbook of Neurotoxicology. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1995.

4 Krantz A, Dorevitch S. Metal exposure and common chronic diseases: a guide for the clinician. Dis Mon. 2004;50:220-262.

5 Hartman DE. Neuropsychological Toxicology: Identification and Assessment of Human Neurotoxic Syndromes. New York: Pergamon, 1988.

6 Bolla KI. Use of neuropsychological resting in idiopathic environmental testing. Occup Med. 2000;15:617-625.

7 Graeme KA, Pollack CVJr. Heavy metals toxicity, part I: arsenic and mercury. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:45-56.

8 National Advisory Council for Environmental Policy and Technology Report of Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993.

9 Bellinger D, Levinton A, Waternaux C, et al. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1037-1043.

10 Bolla K, Rignani J. Clinical course of neuropsychological functioning after chronic exposure to organic and inorganic lead. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12:123-131.

11 Schwartz BS, Bolla KI, Stewart W, et al. Decrements in neurobehavioral performance associated with mixed exposure to organic and inorganic lead. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1006-1021.

12 Schwartz BS, Lee BBK, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Occupational lead exposure and longitudinal decline in neurobehavioral test scores. Epidemiology. 2005;16:106-113.

13 Cotzias GC, Horiuchi K, Fuenzalida S, et al. Chronic manganese poisoning: clearance of tissue manganese concentrations with persistence of the neurological picture. Neurology. 1968;18:376-382.

13a Tokuomi H, Uchimo M, Imamura S, et al. Minamata disease (organic mercury poisoning): neuroradiologic and electro-physiologic studies. Neurology. 1982;32:1369-1375.

14 Mittal BV, Desai AP, Khade KR. Methyl alcohol poisoning: an autopsy study of 28 cases. J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:9-13.

15 Benignus VA. Neurobehavioral effects of toluene: a review. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1981;3:408-415.

16 Gordon MF, Mercandetti M. Carbon monoxide poisoning producing purely cognitive and behavioral sequelae. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1989;2:145-152.

17 Baker SR, Williamson CF. The Effects of Pesticides on Human Health. Advances in Modern Environmental Toxicology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Scientific Co., 1990.

18 Wesseling C, Keifer M, Ahlbom A, et al. Long-term neurobehavioral effects of mild poisoning with organophosphate and N-methyl carbamate pesticides among banana workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:27-34.

19 Kamel F, Hoppin JA. Association of pesticide exposure with neurologic dysfunction and disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:950-958.

20 Seneviratne U, Dissanayake S. Neurological manifestations of snake bite in Sri Lanka. J Postgrad Med. 2002;48:227-275.

21 Gold BS, Barish RA, Dart RC. North American snake envenomation: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;2:423-443.

22 Getahun H, Lambein F, Vanhoorne M, et al. Neurolathyrism risk depends on type of grass pea preparation and on mixing with cereals and antioxidants. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:169-178.

23 Erbguth FJ. Hostorical notes on botulism, clostridium botulinum, botulinum toxin, and the idea of the therapeutic use of the toxin. Mov Disord. 2004;8:S2-S6.

24 Krishna S, Puri V. Infant botulism: case reports and review. J Ky Med Assoc. 2001;99:143-146.

25 Cox N, Hinkle R. Infant botulism. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1388-1392.

26 Sharma SK, Whiting RC. Methods for detection of Clostridium botulinum toxin in foods. J Food Prot. 2005;68:1256-1263.

CHAPTER 111 ENVIRONMENTAL TOXINS AND DISORDERS OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Individual cases of lead poisoning were reported as early as 200 B.C. Nevertheless, the need for the evaluation and treatment of the medical effects caused by exposure to chemicals was not recognized until the 20th century. Many of the offending chemicals affect both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS), and high-level exposure often results in delirium, seizures, or coma.1–4 Although residual effects can include mood and cognitive disorders, they are often not attributed to exposure to these chemicals.

Because the diagnosis of toxin-mediated neurological deficits is one of exclusion, it is important to substantiate a history of significant exposure. Neurological examination and neuroimaging techniques are not very helpful in making a specific diagnosis of toxic encephalopathy but might rule out other causes for the patient’s clinical presentation.5,6 Neuropsychological assessment is essential in the evaluation of these patients. However, decrements in performance on these tests may be erroneously interpreted by clinicians who are not versed in neurobehavioral toxicology. In addition, evaluation of toxic effects on the brain must be considered in the context of each patient’s personality because psychiatric changes can be primary or secondary to chemical exposure.

The clinical manifestations that result from exposure to distinct classes of agents (e.g., metals, organic solvents) are described in this chapter. However, a patient exposed to a certain chemical might not necessarily suffer from all of the symptoms associated with that substance. As with any diagnostic process, the differential diagnosis of neurotoxic exposure, neurological disorders, psychiatric diathesis, or malingering is based on the combined evidence derived from occupational and medical histories; from neurological, psychiatric, and neuropsychological examination findings; and from results of appropriate ancillary studies.

METAL INTOXICATION

Arsenic

Cause and Pathogenesis

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health estimates that about 900,000 workers have potential daily exposure to arsenic. Arsenic poisoning occurs mainly via the oral route. The metal is stored in the liver, kidneys, intestines, spleen, lymph nodes, and bones. After a few days, arsenic is also deposited in hair, where it can stay for many years. Arsenic is excreted slowly in the urine and in the feces, and it takes as long as 2 weeks for a single large dose of the toxin to be excreted. Arsenic affects oxidative metabolism and prevents the transformation of thiamine into acetyl–coenzyme A, rendering patients thiamine deficient. Organic arsenicals release the poison slowly and are therefore less likely to produce acute symptoms than is the elemental metal. Brains of patients who die of arsenic encephalopathy exhibit congestion, hemorrhagic lesions throughout the white matter, and areas of necrosis. Peripheral nerves exhibit decreased numbers of myelinated fibers and degenerative changes, including swelling, granularity, and a reduction in the number of axons.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Acute toxicity is characterized by fever, headaches, anxiety, and vertigo. Seizures are common. Neurological examination reveals nystagmus, increased tendon reflexes, neck stiffness, and sometimes paralysis.7 Mees’ lines (white lines in the nails) usually appear 2 to 3 weeks after acute exposure to arsenic. Encephalopathy with marked excitement followed by lethargy and signs of acute peripheral neuropathy can develop within a few hours. In patients with fatal acute poisoning, coma and death ensue within a few days. Patients with subacute or chronic arsenic encephalitis can suffer from relentless headaches, physical and mental fatigue, vertigo, restlessness, and focal pareses. Spinal cord involvement is associated with weakness, sphincter disturbances, and motor and sensory impairments. Optic neuritis, manifested by cloudy vision and visual field defects, can also occur subacutely or be delayed for years. In general, a mixed sensory and motor neuropathy develops within 7 to 10 days after ingestion of toxic amounts of arsenic, and patients often complain of severe burning sensation in the soles of the feet. Long-standing cognitive changes have been reported.

Arsenic intoxication should be considered in a patient with severe abdominal pain, dermatitis, painful peripheral neuropathy, and seizures. A history of arsenic exposure and toxic arsenic levels in hair, urine, or nails confirm the diagnosis. Arsenic is poorly tolerated in the presence of alcohol. Therefore, patients with alcohol-related disease have a greater risk of developing arsenic neuropathy. Although hair and nail samples may be useful, measurement of urinary arsenic levels is the test of choice. A level of arsenic in urine (24-hour measurement) greater than 50 μg/g creatinine is considered elevated. Because urinary level may be high after ingestion of seafood, a dietary history should be obtained. More reliable values can be obtained by measuring urinary inorganic arsenic metabolites: monomethylarsonic acid and dimethylarsinic acid.

Management

In patients with acute oral ingestion of arsenic, gastric lavage with electrolyte replacement is recommended. Excretion of absorbed arsenic can be enhanced by chelation with dimercaprol (British antilewisite), D-penicillamine, or dimercaptosuccinic acid. Chelating agents can reverse or prevent the attachment of heavy metals to various essential body chemicals (Table 111-1). Although chelating agents may alleviate the acute symptoms, they might not improve chronic symptoms such as peripheral neuropathy or encephalopathy. Dimercaprol treatment is not considered effective after the appearance of neuropathy. Intravenous fluids for dehydration and morphine for abdominal pain are also recommended. Prognosis with severe arsenic poisoning is poor, with a mortality rate of 50% to 75%, usually within the first 48 hours.

Lead

Inorganic Lead

Cause and Pathogenesis

Lead poisoning has a very long history. Although it was identified as early as 200 B.C., it remains a common occurrence even today. More than 1 million workers in more than 100 occupations are exposed to lead. In lead-related industries, workers not only inhale lead dust and lead fumes but may eat, drink, and smoke in or near contaminated areas, increasing the probability of lead ingestion. Family members can also be exposed to lead dust by workers who do not wash thoroughly before returning to their homes. Other sources of lead exposure include surface dust and oils. The de-leading of gasoline has significantly decreased that source of lead exposure. The current major sources of lead in the environment are lead paint in homes built before 1950 and lead used in plumbing, which was restricted in 1986. In 1991, median blood levels of lead in adults in the United States were estimated at 6 μg/dL.8

Children 5 years old or younger are especially vulnerable to the toxic effects of lead. Elevated lead levels in children are caused by pica (compulsive eating of nonfood items) or by the mouthing of items contaminated with lead from paint dust. Children also absorb and retain more lead than do adults. For example, approximately 10% of ingested lead is absorbed by adults whereas 40% to 50% of ingested lead is absorbed by children. Young children with iron deficiency have increased lead absorption. The risk of in utero exposure is high because lead readily crosses the placenta.9

After inorganic lead is absorbed, it binds to erythrocytes and is excreted unchanged in humans. The rate of absorption depends on age and nutritional status. For example, iron and calcium deficiencies cause significant increases in lead absorption. Once absorbed, lead is also distributed to soft tissues (kidney, bone marrow, liver, and brain) and mineralized tissues (bones and teeth); 95% of the total body burden of lead is found in teeth and bones. Pregnancy, menopause, and chronic diseases are associated with mobilization of lead from bones and increased levels in blood. The turnover rate of lead in cortical and trabecular bone is slow, its half-life ranging from years to decades. Lead excretion is through the kidneys or the biliary system into the gastrointestinal tract. Although a person’s blood levels may begin to return to normal after a single exposure, the total body burden of lead may still be elevated. For lead poisoning to occur, significant acute exposures are not necessary because the body accumulates lead over time and releases it slowly.

Lead encephalopathy has been associated with softening and flattening of convolutions in the brain. On occasion, there are punctate hemorrhages, dilation of the vessels, and dilation of the ventricular system, especially in the frontal lobes. Histologically, extensive involvement of the ganglion cells is evident. The developing brain appears to be vulnerable to levels of lead that were once thought to cause no harmful effects.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

In children, exposure to toxic doses of lead can cause listlessness, drowsiness with clumsiness, and ataxia. Very high levels can cause convulsions, respiratory arrest, and coma. A diagnosis of lead toxicity should be considered in a child who shows changes in mental status, gait disorder, or seizures. Chronic low-level exposure in children can result in attention and learning disabilities or in cognitive decline. Children chronically exposed to lead have been reported to show a drop in mean verbal IQ score of 4.5 points. Primary school children with high lead levels in teeth, but without a history of lead exposure, had larger deficits in speech and language processing, psychometric intelligence scores, and classroom performance than did children with lower levels of lead. Children with high lead levels in their teeth are sevenfold more likely not to graduate from high school. They have a greater prevalence of poor eye-hand coordination, reading disabilities, poor fine motor skills, and poor reaction time.9–11

At present, acute lead encephalopathy resulting from industrial exposure is not common. Signs and symptoms generally include delirium, combative irrational behavior, sleep disturbances, decreased libido, increased distractibility, increased irritability, and mental status changes marked by psychomotor slowing, memory dysfunction, and seizures.12

Involvement of both sensory and motor peripheral nerves can be seen in adults with chronic lead intoxication. Sensory complaints include paresthesias and pain. Motor signs include fasciculations, atrophy, and weakness. Severe cases can manifest with wristdrop and footdrop. Extensive bilateral neuropathy involving the fingers, the hands, and the biceps, triceps, and deltoid muscles has also been reported. In individuals with predominantly motor findings, nerve conduction velocity may not be altered even after significant occupational exposure, but mild slowing in nerve conduction velocity has been reported. Anemia, abnormal kidney function, hypertension, and gout can also occur. Miscarriage and stillbirths are common among women who work with lead. Men may suffer from reduced sperm motility and/or counts.

Patients with lead intoxication show increased levels of whole blood lead, free erythrocyte protoporphyrins (FEP), and urinary coproporphyrins. Blood lead levels reflect recent exposure to lead, whereas free erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels reflect chronic exposure. Free erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels begin to rise in adults once blood lead levels reach 30 to 40 μg/dL. These levels may remain elevated for several months even after exposure has ceased. The body burden of lead is measured through diagnostic chelation. Urinary lead excretion is measured after infusion of 1 g of calcium ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA). More than 600 g of lead excreted in the urine over a period of 72 hours is considered an elevated level. A noninvasive method of measuring body lead burden in bone is x-ray fluorescence. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are not useful in making a diagnosis of lead exposure. In some studies, neuropsychological evaluation of workers with lead blood levels below 30 μg/dL has revealed decrements in visuomotor integration, psychomotor speed, short-term visual and verbal memory, and problem-solving skills.

Management