Chapter 18 Environmental medicine

Disease and the environment

Nutrition, poverty and affluence

Nutrition, poverty and affluence

Purity of water sources, sanitation and atmospheric pollution

Purity of water sources, sanitation and atmospheric pollution

Environmental disasters and accidents

Environmental disasters and accidents

Background ionizing radiation and man-made radiation exposure, deliberate or accidental

Background ionizing radiation and man-made radiation exposure, deliberate or accidental

Political forces determining levels of healthcare, preventative strategies and effects of war on civilian populations.

Political forces determining levels of healthcare, preventative strategies and effects of war on civilian populations.

Heat

Cold

Frostbite: the local cold injury that follows freezing of tissue

Frostbite: the local cold injury that follows freezing of tissue

Non-freezing cold injury: the damage – usually to feet – following prolonged exposure to TEnv between 0 and 5°C, usually in damp conditions.

Non-freezing cold injury: the damage – usually to feet – following prolonged exposure to TEnv between 0 and 5°C, usually in damp conditions.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs in many settings.

Severe hypothermia

In severe hypothermia, people look dead. Always exclude hypothermia before diagnosing brainstem death (see p. 897). Warm gradually, aiming at a 1°C/hour increase in TCore. Direct mild surface heat from an electric blanket can be helpful. Treat any underlying condition promptly, e.g. sepsis. Monitor all vital functions. Correct dysrhythmias. Check for sedative drugs.

High altitudes

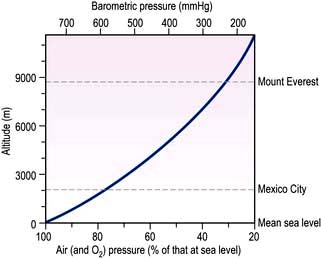

The partial pressure of atmospheric oxygen – and hence alveolar and arterial oxygen – falls in a near-linear relationship as barometric pressure falls with increasing altitude (Fig. 18.1).

On land, below 3000 m there are few clinical effects. The resulting hypoxaemia causes breathlessness only in those with severe cardiorespiratory disease. Above 3000–3500 m hypoxia causes a spectrum of related syndromes that affect high-altitude visitors, principally climbers, trekkers, skiers and troops (Table 18.1), especially when they exercise. These conditions occur largely during acclimatization, a process that takes several weeks and once completed can enable man to live – permanently if necessary – up to about 5600 m. At greater heights, although people can survive for days or weeks, deterioration due to chronic hypoxia is inevitable.

| Condition | Incidence (%) | Usual altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|

|

Acute mountain sickness |

70 |

3500–4000 |

|

Acute pulmonary oedema |

2 |

4000 |

|

Acute cerebral oedema |

1 |

4500 |

|

Retinal haemorrhage |

50 |

5000 |

|

Deterioration |

100 |

6000 and above |

|

Chronic mountain sickness |

Rare |

3500–4000 |

Acute mountain sickness (AMS)

Chronic mountain sickness

Coronary artery disease and hypertension are rare in high-altitude native populations.

FURTHER READING

Clarke C. High altitude and mountaineering expeditions. In: Warrell D, Anderson S (eds). Expedition Medicine, 2nd edn. London: Royal Geographical Society; 2008.

Grocott MP, Martin DS, Levett DZ et al. Arterial blood gases and oxygen content in climbers on Mount Everest. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:140–149.

Diving

Free diving by breath-holding is possible to around 5 metres, or with practice to greater depths. Air can be supplied to divers by various methods. With a snorkel, providing air to a depth of c. 0.5 metres, inspiratory effort is the limiting factor. At depths >0.5 metres, i.e. with a longer snorkel tube, forced negative-pressure ventilation can cause pulmonary capillary damage with haemorrhagic alveolar oedema. Scuba divers, i.e. recreational sports divers descending to 30 metres, carry bottled compressed air, or a nitrogen–oxygen mixture. Divers who work at great depths commercially breathe helium–oxygen or nitrogen–oxygen mixtures, delivered by hose from the surface. Ambient pressures at various depths are shown in Table 18.2.

| Water depth (m) | Pressure | |

|---|---|---|

| Atmospheres | mmHg | |

|

0 |

1 |

760 |

|

10 |

2 |

1520 |

|

50 |

6 |

4560 |

|

90 |

10 |

7600 |

Problems during descent

Sinus squeeze is intense local pain due to blockage of the nasal and paranasal sinus ostia.

Problems during and following ascent

FURTHER READING

Bennett P, Elliot D. The Physiology and Medicine of Diving, 5th edn. London: WB Saunders; 2002.

Edmonds C, Thomas B, McKewzie B, Pennefather J. Diving Medicine for Scuba Divers, 2012 edn. Available at: www.divingmedicine.info.

Melamed Y, Shupak A, Bitterman H. Medical problems associated with underwater diving. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:30–36.

Drowning and near-drowning

Wet drowning

Treatment and prognosis

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be started immediately (see p. 691). Patients have survived for up to 30 minutes underwater without suffering brain damage – and sometimes for longer periods if TWater is near 10°C. Survival is probably related to the protective role of the diving reflex; submersion causes bradycardia and vasoconstriction. Oxygen consumption is also decreased by hypothermia.

Ionizing radiation

Dosage is measured in joules per kilogram (J/kg); 1 J/kg = 1 gray (1 Gy) = 100 rads.

Radiation differs in the density of ionization it causes. Therefore a dose-equivalent called a sievert (Sv) is used. This is the absorbed dose weighted for the damaging effect of the radiation. The annual background radiation is approximately 2.5 mSv. A chest X-ray delivers 0.02 mSv, and CT of the abdomen/pelvis about 10 mSv (see Table 9.5). A cumulative risk of cancer following repeated imaging procedures has been established and reduction of X-ray exposures should be made if possible.

Acute radiation sickness

Many systems are affected; the extent depends on the dose of radiation (Table 18.3).

| Acute effects | Delayed effects |

|---|---|

|

Haemopoietic syndrome |

Infertility |

|

Gastrointestinal syndrome |

Teratogenesis |

|

CNS syndrome |

Cataract |

|

Radiation dermatitis |

Neoplasia: |

|

|

Acute myeloid leukaemia |

|

|

Thyroid |

|

|

Salivary glands |

|

|

Skin |

|

|

Others |

Late effects of radiation exposure

The sequelae of therapeutic radiation – early, early-delayed and late-delayed radiation effects are discussed on page 448. Focussing techniques are used to target radiation towards the field being treated; radiosensitive structures such as the ovaries are protected by shielding.

Electric shock

Pain and psychological sequelae. The common domestic electric shock is typically painful, rarely fatal or followed by serious sequelae. Nevertheless, it is an unpleasant and intensely frightening experience. A brief immediate jerking episode can occur, that is not an epileptic seizure. There is usually no lasting neurological, cardiac or skin damage. More serious effects are distinctly rare following accidents in the home or in industry, but claims by survivors following industrial accidents are frequently made.

Pain and psychological sequelae. The common domestic electric shock is typically painful, rarely fatal or followed by serious sequelae. Nevertheless, it is an unpleasant and intensely frightening experience. A brief immediate jerking episode can occur, that is not an epileptic seizure. There is usually no lasting neurological, cardiac or skin damage. More serious effects are distinctly rare following accidents in the home or in industry, but claims by survivors following industrial accidents are frequently made.

Cardiac, neurological and muscle damage. Ventricular fibrillation, muscular contraction and spinal cord damage can follow a major shock. These are seen typically following lightning strikes with exceedingly high voltage and amperage.

Cardiac, neurological and muscle damage. Ventricular fibrillation, muscular contraction and spinal cord damage can follow a major shock. These are seen typically following lightning strikes with exceedingly high voltage and amperage.

Electrical burns. These are commonly restricted to the skin – non-fatal lightning strikes cause fern-shaped burns. Muscle necrosis and spinal cord damage can also occur.

Electrical burns. These are commonly restricted to the skin – non-fatal lightning strikes cause fern-shaped burns. Muscle necrosis and spinal cord damage can also occur.

Electrocution. This means death following ventricular fibrillation, either accidentally, or deliberately as a method of execution. In the USA, at executions an initial voltage of >2000 volts was applied for some 15 seconds in the electric chair, causing loss of consciousness and ventricular fibrillation before the voltage was lowered. The TCore during the execution process would sometimes reach >50°C, leading to severe damage to internal organs.

Electrocution. This means death following ventricular fibrillation, either accidentally, or deliberately as a method of execution. In the USA, at executions an initial voltage of >2000 volts was applied for some 15 seconds in the electric chair, causing loss of consciousness and ventricular fibrillation before the voltage was lowered. The TCore during the execution process would sometimes reach >50°C, leading to severe damage to internal organs.

Smoke

Smoke is air containing toxic and/or irritant gases and carbon particles, coated with organic acids, aldehydes and synthetic materials. Carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, sulphuric and hydrochloric acids and other toxins may also be present. The highly toxic polyvinyl chloride is no longer used in household goods. Air pollution is discussed on page 807.

Bioterrorism/biowarfare

Potential pathogens

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, have developed a classification of potential biological agents (Table 18.4).

| Category | Pathogens |

|---|---|

|

A.Very infectious and/or readily disseminated organisms: high mortality with a major impact on public health |

Smallpox, anthrax, botulinism, plague |

|

B.Moderately easy to disseminate organisms causing moderate morbidity and mortality |

Q fever, brucellosis, glanders, food-/water-borne pathogens, influenza |

|

C.Emerging and possible genetically engineered pathogens |

Viral haemorrhagic fevers, encephalitis viruses, drug-resistant TB |

Adapted from Khan AS, Morse S, Lillibridge S. Public health preparedness for biological terrorism in the USA. Lancet 2000; 356:1179–1182, reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Smallpox

Smallpox is a highly infectious disease with a mortality >30%. There is no proven therapy, but there is an effective vaccine. Universal vaccination was stopped in the early 1970s: the vast majority of the world’s population is now unprotected against the variola virus (see p. 101). The potential exists for a worldwide epidemic of smallpox, possibly initiated by a bioterrorist act.

Smallpox has an incubation period of around 12 days, allowing any initial source of infection to go undetected until the rash (Fig. 18.2), similar to chickenpox, develops on the 2nd or 3rd day of the illness. Infection is transmitted by the airborne route; the patient becomes infectious to others 12–24 hours before the rash appears, thus allowing a potential infected volunteer to pass infection to others before being recognized as suffering from smallpox. If vaccines were to be administered widely to those potentially infected within 3 days of contact, an epidemic might well be prevented. Smallpox virus is stored in two secure laboratories – in Russia and in the USA. Supplies of vaccine are potentially available worldwide.

Anthrax

In late 2001, anthrax organisms (see p. 132) were sent through the US mail and infected 22 individuals. Of these, 11 developed pulmonary anthrax, five of whom died; 11 suffered from cutaneous anthrax.

Building-related illnesses

Specific building-related illnesses

Legionnaires’ disease (see p. 836) can follow contamination of air-conditioning systems.

Humidifier fever (see p. 854) is also due to contaminated systems, probably by fungi, bacteria and protozoa. Many common viruses are potentially transmissible in an enclosed environment, e.g. the common cold, influenza and rarely pulmonary TB. Allergic disorders, e.g. rhinitis, asthma and dermatitis, also occur following exposure to indoor allergens such as dust mites and plants. Office equipment, e.g. fumes from photocopiers, has also been implicated. Passive smoking (see p. 807) is no longer an issue in Europe and North America, following legislation against smoking.