Chapter 30 Envenomation

Australia is home to many venomous creatures. Australian animals that are important in causing envenoming in humans include snakes, spiders, octopuses, fish and other marine creatures. The distribution of venomous creatures is wide, and each region has its own pattern of envenomation. Local knowledge is very important and local expert knowledge can be invaluable.

SNAKEBITE

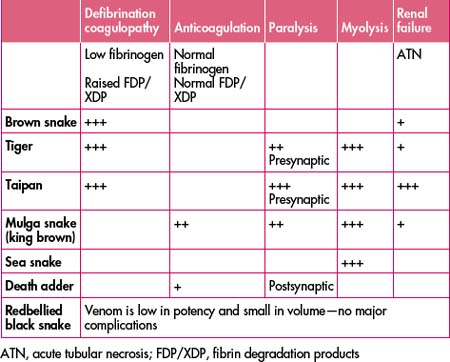

Australia is home to a number of the most venomous snakes in the world. Snake venom is a complex mixture of substances. Australian snakes produce venoms that have a range of clinical effects including neurotoxic (presenting as progressive paralysis), myotoxic (causing rhabdomyolysis and subsequent renal failure) or severe coagulation disturbances and haemolysis (Table 30.1).

First aid: the pressure-immobilisation technnique

Snake venom spreads via the lymphatics. The pressure-immobilisation method of first aid prevents spread of the venom via the lymphatics and can prevent clinical envenomation. It involves applying a firm broad bandage, commencing at the site of the bite, and then applying the bandage over the entire limb, extending both proximally and distally. The pressure is the same as that used for a sprained ankle. A splint is then applied to the limb, to immobilise the limb and reduce muscle contraction to further reduce lymphatic spread of the venom. The patient is then kept as still as possible and transported to hospital.

If a patient arrives with symptoms of envenomation and does not have a bandage applied, then one should be applied.

Table 30.2 Use of the pressure-immobilisation technique of first aid

| Pressure-immobilisation is recommended for | Do not use pressure-immobilisation first aid for |

|---|---|

| All Australian venomous snake bites, including sea snake bites | Redback spider bites |

| Funnel web spider bites | Other spider bites, including mouse spiders, white tailed spiders |

| Box jellyfish stings (if possible) | Bluebottle jellyfish stings |

| Bee, wasp and ant stings in allergic individuals | Other jellyfish stings |

| Blue-ringed octopus bites | Stonefish and other fish stings |

| Cone snail (cone shell) stings | Bee and wasp stings in non-allergic individuals |

| Australian paralysis tick envenomation | Bites or stings by scorpions, centipedes, beetles |

Adapted with permission of the Australian Venom Research Unit

Venom detection kit

The venom detection kit is used by trained laboratory staff and takes about 20 minutes to complete.

Antivenom

Antivenom is the definitive treatment for a patient with systemic envenomation. The administration of antivenom can reverse the clinical effects of envenomation. The treatment of envenomation following snakebite involves the administration of adequate quantities of the appropriate antivenom.

Laboratory testing

Urine should be tested for myoglobin and blood.

Laboratory tests may be normal initially and will need repeating. If all tests are normal then the first aid bandages should be removed and pathology tests repeated after 2–3 hours. Onset of coagulopathy may be delayed and blood tests should be repeated.

SPIDER BITES

Redback spider (Latrodectus hasseltii)

The redback bite is usually felt as an initial mild sting, with no signs of a bite at the site. Fifteen minutes to 1 hour later the bite site may become painful. The pain can become severe and extend to the regional lymph nodes. Following this, pain may extend to the whole limb and the abdomen, and headache may occur. There may be nausea, malaise and hypertension. An area of sweating may develop surrounding the bite site. The patient may be sweating profusely and this may be generalised or localised to the bite site, or in an area remote from the bite.

Funnelweb spider (Atrax spp.)

All Sydney funnelweb spider bites should be admitted for close observation.

MARINE ENVENOMATION

Box jellyfish or sea wasp (Chironex fleckeri)

Early administration of antivenom may result in reduced pain and reduces skin necrosis and scarring.

Irukandji (Carukia barnesi)

No antivenom is available to treat irukandji envenomation. The best form of first aid is currently unclear.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Unexplained coagulopathies, muscle pain or weakness should include envenomation as a differential.

The decision to administer antivenom when clinically indicated should not be delayed.

Adequate antivenom should be used as indicated on either clinical or laboratory grounds.

Being bitten does not automatically indicate the need for antivenom administration.

A positive result for a venom detection kit does not indicate the need for antivenom administration.

Australian Venom Research Unit website. Available: http://www.pharmacology.unimelb.edu.au/avruweb/index.htm.

Clinical toxinology website. Available: http://www.toxinology.com.

CSL snake venom detection kit: technical information. Melbourne: Commonwealth Serum Laboratories Limited

Sutherland S., Tibbals J. Australian animal toxins, 2nd edn. USA: Oxford University Press; 2001.

White J. Bites and stings. Current Therapeutics. 2003;43(2):8-45.

White J. CSL antivenom handbook, 2nd edn. Melbourne: Commonwealth Serum Laboratories Limited, 2001.

White J. Snakebite and spiderbite: a management protocol for NSW. Sydney: NSW Health Department; 1998.