Chapter 11 ENT problems

Introduction

The vast majority of ENT (ear, nose and throat) problems that present in the pre-hospital setting are minor in nature. However, occasionally innocuous symptoms can develop into life-threatening conditions which require immediate assessment and treatment. The objectives of this chapter are outlined in Box 11.1.

Box 11.1 Chapter objectives

To identify any patients who have a normal primary survey but have an obvious need for hospital admission

To identify any patients who have a normal primary survey but have an obvious need for hospital admission To undertake a secondary survey (full assessment) including history and examination targeted to the presenting symptom

To undertake a secondary survey (full assessment) including history and examination targeted to the presenting symptomPrimary survey

The primary survey (Box 11.2) is a rapid assessment tool which uses the ABC principles to look for an immediately life-threatening condition.

Box 11.2 Primary survey

If any observations below are present treat immediately and transfer to hospital:

ENT conditions can be immediately life-threatening by causing an A, B or C problem:

A Airway obstruction/compromise – inhaled foreign body, epiglottitis, quinsy, anaphylaxis/angio-oedema, croup, facial fractures

A Airway obstruction/compromise – inhaled foreign body, epiglottitis, quinsy, anaphylaxis/angio-oedema, croup, facial fractures C Circulatory compromise – haemorrhage, e.g. epistaxis, from facial fracture, secondary haemorrhage following ENT surgery, e.g. post-tonsillectomy.

C Circulatory compromise – haemorrhage, e.g. epistaxis, from facial fracture, secondary haemorrhage following ENT surgery, e.g. post-tonsillectomy.Patients with a normal primary survey but with obvious need for hospital admission

Patients with all of the above conditions can show a spectrum of severity of symptoms and signs, which can deteriorate. It is essential to remember that in the early stages of these conditions, patients may not have significant abnormal physical signs. The recognition of developing airway obstruction is critical and management of the condition may require the use of airway adjuncts to maintain adequate oxygenation. If there is complete airway obstruction and airway adjuncts have failed, prompt insertion of a surgical airway may be required as a last resort. It is important to monitor patients with respiratory distress for deterioration and exhaustion. In the case of haemorrhage the body will initially compensate. Therefore cases leading to hypovolaemia should be treated by arresting the haemorrhage and administering fluid to maintain a radial pulse.

should be admitted to hospital for further investigation and management. However, not all cases of croup or epistaxis will require hospital admission. Management of the individual conditions is discussed below or in other chapters of this book.

Secondary survey

Patients still remaining after the primary survey require a thorough assessment to determine optimal treatment and discharge (see Chapter 2).

History and examination. Should be targeted to the presenting symptom and associated systems. Examination of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems is always necessary. This should be supplemented with abdominal assessment when glandular fever is suspected, looking for hepatosplenomegaly, and examination of the central nervous system if vertigo or facial weakness is the presenting symptom.

History and examination. Should be targeted to the presenting symptom and associated systems. Examination of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems is always necessary. This should be supplemented with abdominal assessment when glandular fever is suspected, looking for hepatosplenomegaly, and examination of the central nervous system if vertigo or facial weakness is the presenting symptom.Differential diagnosis

Table 11.1 shows details of the differential diagnoses classified by presenting symptom.

Table 11.1 Differential diagnoses classified by presenting symptom

| Presenting symptom | ENT diagnoses | Other differential diagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| Nose bleed | Anterior bleed Posterior bleed Traumatic Post surgery |

Underlying bleeding disorder |

| Sore throat | Tonsillitis Pharyngitis Glandular fever Candida Quinsy Stevens–Johnson syndrome Ramsey–Hunt syndrome |

Angina Gastro-oesophageal reflux Tobacco usage Occupational irritants |

| Sore ears | Otitis externa Viral otitis media Bacterial otitis media Perforated tympanic membrane Eustachian tube dysfunction Mastoiditis Ramsey–Hunt syndrome |

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction Upper GI and airway neoplasms Dental Cervical spondylosis |

| Foreign body | Ears Nose Airway |

|

| Difficult/noisy breathing | Foreign body Epiglottitis Croup Anaphylaxis Bacterial tracheitis Smoke inhalation |

Asthma COPD |

| Vertigo | Vestibular neuronitis Meniere’s Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo |

Cerebellar CVA Other central causes |

| Facial/tooth pain | Sinusitis Dental abscess |

Shingles Trigeminal neuralgia |

| Facial weakness | Bells palsy Ramsey–Hunt syndrome |

CVA |

| Sudden hearing loss | Wax impaction Perforated TM |

CVA |

| Trauma | Facial fractures Perforated TM |

Presenting symptoms, history, examination and treatment

Nose bleed

The following points in the history are important for the management of a patient with a nose bleed:

When examining the patient try to locate the side of the bleeding, look at the linearity of the nose (if asymmetrical, is this due to recent trauma?); check the appearance of the septum and Little’s area. The latter is the area of the septum seen through the nostrils when the nasal tip is tilted upwards (Fig. 11.1). Blood vessels in Little’s area are prone to bleeding. Check the throat for blood running down the nasopharynx. Ensure you get a set of vital signs and examine the cardiovascular system looking for any indication of shock.

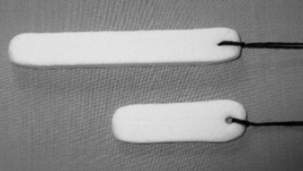

If the bleeding fails to respond to simple first aid measures packing should be applied to the nasal cavity from which the bleed is suspected to have originated. The simplest pack and the easiest to insert is the nasal tampon (Fig. 11.2). However, the nose can be packed with ribbon gauze if available and the healthcare professional is competent at the procedure. Nasal tampons are supplied small and flat but expand and take on the contours of the cavity when they are hydrated with either blood or saline. The leading edge of the nasal tampon should be lubricated prior to insertion. It should then be inserted in a horizontal plane into the nasal cavity. If the nasal tampon does not expand with the blood in the nose, saline should be dripped onto the external end of the nasal tampon until it expands and causes compression. The thread of the tampon should be secured with tape and a nasal sling may be applied to soak up any excess blood.

If anterior packing fails to stop the bleeding after 15 minutes a posterior bleed should be suspected (approx. 5% of bleeds). These require packing using a long nasal tampon, an epistaxis balloon or a Foley catheter with an anterior pack depending on what is available (Fig. 11.3). Long (posterior) nasal tampons are inserted in the same way as an anterior tampon. Some epistaxis balloons have an anterior and posterior balloon. The balloon is lubricated with saline and inserted, again in a horizontal plane. The posterior balloon is inflated to the recommended volume, gentle traction is applied to position the balloon in the posterior nasal space and then the anterior balloon is inflated to the recommended volume. Foley catheters and single balloon epistaxis catheters are inserted in the same way but do not have an anterior balloon and therefore an anterior pack is necessary. The Foley catheter must be secured with care taken to prevent pressure necrosis of the nasal tissues. All patients with a posterior bleed require admission (Box 11.3). If a large volume of blood has been lost, oxygen, venous access and fluid resuscitation may be necessary.

Fig. 11.3 Posterior and anterior nasal tampons, deflated and inflated double balloon epistaxis catheters and single posterior space epistaxis balloon catheter (reproduced with permission of BASICS Scotland).

Box 11.3 Patients with a nose bleed – who needs to go to hospital?

All patients with a posterior pack must be admitted to hospital. They require analgesia and close monitoring particularly of vital signs and O2 saturations

All patients with a posterior pack must be admitted to hospital. They require analgesia and close monitoring particularly of vital signs and O2 saturations Patients with a history of recent nasal surgery should be discussed with the appropriate surgical team

Patients with a history of recent nasal surgery should be discussed with the appropriate surgical team Patients taking anticoagulants may be treated in the community if a recent INR is known and over-anticoagulation is not suspected

Patients taking anticoagulants may be treated in the community if a recent INR is known and over-anticoagulation is not suspected Patients with an anterior pack and significant other medical illness such as angina or COPD should be considered for admission for close monitoring depending on severity of co-morbid conditions. By packing the patient’s nose we cause respiratory compromise that may lead to exacerbations of pre-existing illnesses

Patients with an anterior pack and significant other medical illness such as angina or COPD should be considered for admission for close monitoring depending on severity of co-morbid conditions. By packing the patient’s nose we cause respiratory compromise that may lead to exacerbations of pre-existing illnessesSore throat

Several features need to be elicited when dealing with patients with sore throats:

Pharyngitis/tonsillitis/glandular fever/candida

Candidal sore throats can be suspected on history and confirmed on examination by the presence of white plaques adherent to the mucosa of the palate and gums (Fig. 11.4). Treatment is with a topical antifungal such as nystatin. If the patient is immunocompromised then systemic antifungals may be necessary.

Peritonsillar cellulitis and quinsy

Both of these conditions are complications of bacterial tonsillitis and should be suspected in someone whose sore throat gets substantially worse and who becomes more unwell than is usual with an uncomplicated tonsillitis. Peritonsillar cellulitis is the presuppurative stage of quinsy – a localised collection of pus above the tonsil. A patient with either condition will complain of a severe unilateral sore throat and difficulty swallowing. The patient may also complain of ipsilateral (on the same side) ear pain and pain on movement of the neck. Examination of the throat will reveal a very swollen, red area above and to the side of the inflamed tonsil. The uvula (the tissue that hangs down from the roof of the mouth at the back of the palate) may be pushed to one side. Enlarged cervical lymph nodes are the cause of the neck pain. If peritonsillar cellulitis is the diagnosis there will be relatively little trismus. If trismus is a feature, quinsy should be suspected. There may be a change to the quality of the voice. Treatment may require drainage, intravenous antibiotics and fluids. Suspected cases need to be referred to hospital for assessment and treatment (Box 11.4).

Stevens–Johnson syndrome

This is a rare multisystem illness with widespread vesiculobullous lesions and erosions of the mucous membranes associated with erythema multiforme of the skin (Fig. 11.5). The highest incidence is in the 20–40-year age group; it is twice as common in males and is more common in spring and autumn. Infection (especially Mycoplasma and herpes simplex), drugs (especially antibiotics and anticonvulsants) and malignancies are common precipitating factors; 50% of cases have no identifiable aetiology. Suspected cases should be referred to hospital for assessment as many will require ITU or HDU care.

Non-ENT causes of sore throat

Angina can present with pain in the throat or jaw related to physical exertion. Consider this in middle aged and older patients, with or without a previous history of ischaemic heart disease, with a normal throat examination and no other ENT symptoms. Patients with suspected angina should have an ECG and be given sublingual nitrate (see Chapter 3).

Angina can present with pain in the throat or jaw related to physical exertion. Consider this in middle aged and older patients, with or without a previous history of ischaemic heart disease, with a normal throat examination and no other ENT symptoms. Patients with suspected angina should have an ECG and be given sublingual nitrate (see Chapter 3). Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease can present with a sore throat and persistent cough. Examination often reveals pharyngitis. Consider this in older, overweight individuals with a persistent sore throat with or without a history of dyspepsia.

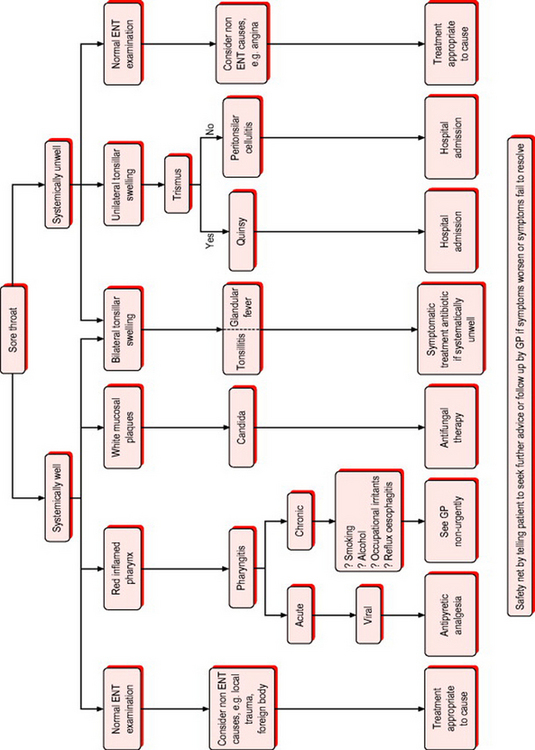

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease can present with a sore throat and persistent cough. Examination often reveals pharyngitis. Consider this in older, overweight individuals with a persistent sore throat with or without a history of dyspepsia.Figure 11.6 shows the sore throat treatment algorithm.

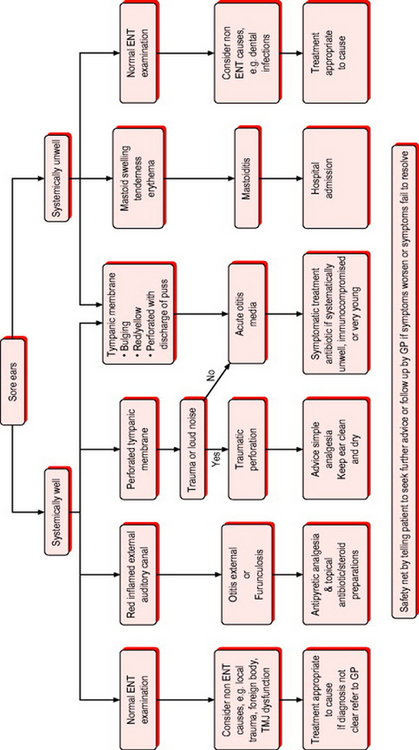

Sore ears/discharging ears

Painful ears are a common complaint, particularly in young children. The pain may originate from the ear itself or be referred from another site. There are some important features to establish about the pain to help make the diagnosis:

Otitis externa/furunculosis

Otitis externa

is an inflammation (usually infective) of the external auditory canal, which can spread to the pinna, periauricular soft tissues, or even the temporal bone. It is common in patients with eczematous ear canal skin and in those who produce trauma with cotton buds. Streptococci, staphylococci, pseudomonas and fungi are the usual infecting organisms. Pressure on the tragus or gentle tugging on the pinna (Fig. 11.7) will cause discomfort. In the early stages the canal is tender and red and there may be a slight watery discharge. As the condition progresses there may be oedema of the canal and accumulation of debris. Treatment is with topical antibiotic and steroid combination drops and simple analgesia. Any associated cellulitis should be treated with systemic antibiotics.

Otitis media

AOM is usually a self-limiting condition. About 80% of AOM will resolve within 3 days without antibiotic treatment. Although there is no definitive consensus on the optimum treatment of AOM in children, the available evidence suggests that antibiotic treatment should not be offered routinely. The mainstay of treatment is analgesia. Both paracetamol and ibuprofen are adequate analgesics. Parents should be reassured and involved in discussions of the pros and cons of antibiotic treatment. A ‘wait and see’ approach may be a good compromise for some people. A prescription for antibiotics can be issued on the day of consultation but not be redeemed unless the condition has not resolved after 72 hours. This has been found to be effective and feasible in two studies.1,2 Although antibiotics should not be routinely prescribed, the following indications may support their selective use:

local signs (such as tympanic perforation and discharge of pus) that suggest the infection is severe.

local signs (such as tympanic perforation and discharge of pus) that suggest the infection is severe.The recommended antibiotics for uncomplicated AOM are shown in Table 11.2.

| Antibiotic treatment | AOM first line | AOM second line (treatment failure) |

|---|---|---|

| No penicillin allergy | Amoxicillin | Co-amoxiclav |

| Penicillin allergy | Azithromycin Erythromycin Clarithromycin |

Azithromycin if erythromycin used first-line OR seek specialist advice from local microbiologist |

There is currently no consensus on the optimal length of treatment with antibiotics for acute otitis media; however the available evidence (Box 11.5) suggests that a 5-day course of antibiotics is usually adequate with the exception of azithromycin where 3 days use is sufficient because of its unique pharmacokinetics. The treatment of AOM with antihistamines and decongestants is not recommended.

Box 11.5 Evidence for the treatment of otitis media

The 2004 SIGN guideline on otitis media3 found that 17 children need to be given antibiotics for one child to benefit from resolution of symptoms

The 2004 SIGN guideline on otitis media3 found that 17 children need to be given antibiotics for one child to benefit from resolution of symptoms The clinical impact of antibiotic treatment in children under 2 years of age may be greater than in older children6 but the frequency of adverse effects seen with antibiotics used to treat AOM may be as high as the NNT required to produce a clinical benefit7,8

The clinical impact of antibiotic treatment in children under 2 years of age may be greater than in older children6 but the frequency of adverse effects seen with antibiotics used to treat AOM may be as high as the NNT required to produce a clinical benefit7,8Perforated tympanic membrane

Tympanic perforations may be secondary to acute otitis media or trauma. Examination of the ear shows loss of the cone of light as the light usually reflects off the tympanic membrane. Perforations may be partial or total. Partial perforations are easier to recognise than total perforations. Those associated with acute otitis media and profuse discharge of pus should be treated with antibiotics. Traumatic perforations do not require initial treatment. All patients with perforations should be told not to put anything in the ear and not to submerge the ear under water. Not all perforations will heal, therefore follow-up by the GP 10–14 days later is required – or sooner if new symptoms develop.

Epiglottitis

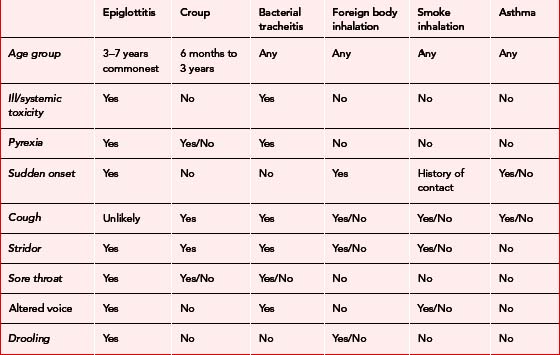

This is a life-threatening condition caused by Haemophilus influenzae infection of the epiglottis. It is now much less common since the advent of Hib vaccination but can occur in those who have not been immunised. Though usually seen in 3–7-year-olds it can occur in adults. The onset of symptoms is rapid with high fever and sore throat being the earliest features. The patient can then develop stridor (a harsh, high-pitched, musical sound produced by turbulent airflow through a partially obstructed airway) and the voice may be muffled or absent. Tachycardia, tachypnoea, swallowing difficulties and drooling may then ensue. The patient will appear toxic, apprehensive and pale. Often they sit upright, leaning forward with neck extended, mouth open and jaw thrust forward – in an attempt to maximise the diameter of the airway. There is usually no cough. Cyanosis, shock, loss of consciousness and complete airway obstruction will ensue unless intervention by a senior ENT surgeon is instigated immediately. Do not attempt to examine the throat. Refer immediately to a hospital with ENT facilities and warn of suspected diagnosis. Give oxygen but do not cause distress and allow the patient to maintain their upright posture. Be prepared to manage the airway en route if necessary. Continue to reassess ABCs during transfer.

Croup

Laryngotracheobronchitis is usually a viral infection. It may be mild or severe and the child can quickly develop respiratory distress. Occurring mainly between the ages of 6 months and 3 years you should suspect if there is pyrexia, a painful barking cough and stridor. All children under the age of 1 year should be admitted to hospital. If there are features of severe respiratory distress (Box 11.6) the child should be admitted to hospital irrespective of age.

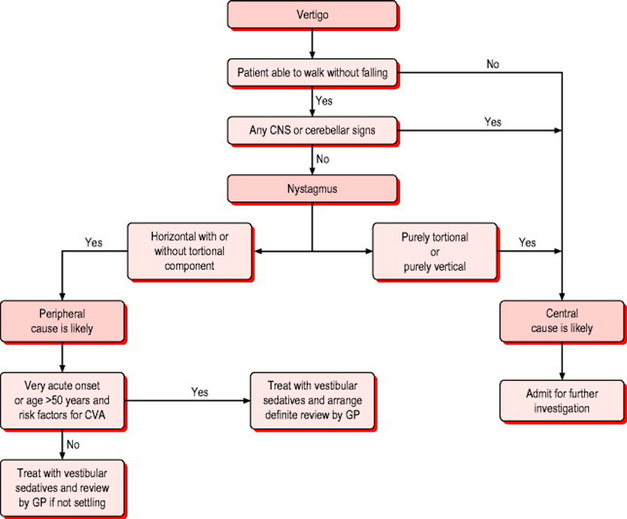

Vertigo9

Vertigo, an illusion of movement, is the cardinal symptom of vestibular dysfunction. Vertigo is typically rotational, but it can be an illusion of tilting to one side or swaying. It is common for acute vertigo to cause a feeling of imbalance during standing or walking. Patients want to lie still and avoid movement. Acute vertigo is accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and autonomic distress of varying degrees of severity. The difficulty is separating the peripheral (otogenic) causes from a central cause (Table 11.4). Peripheral conditions causing vertigo can include external auditory canal obstruction, middle ear infection or trauma, Meniere’s disease and vestibular neuronitis. Central problems presenting with vertigo are usually more serious than the peripheral ones and can include cerebellar infarct or haemorrhage, intracranial space-occupying lesions and demyelinating disease.

Table 11.4 Differentiating between peripheral and central vestibular disorder

| Peripheral vestibular disorder | Central vestibular disorder |

|---|---|

| Nystagmus

Normal CNS examination |

May be:

May be unable to walk without falling

Some additional questions in the history may help:

A detailed examination of the ear and central nervous system (particularly looking for cerebellar signs) is required (Box 11.7). The type of nystagmus, presence of cerebellar or other neurological symptoms or signs, presence of risk factors for stroke and ability of the patient to walk may help to reach a diagnosis (Fig. 11.10).

Box 11.7 Cerebellar examination

Co-ordination tests

Finger–nose test. Ask the patient to touch their nose with a single finger then to touch your finger held about 0.5 m in front of them. Repeat this moving your finger to a different position. Ask the patient to complete the task as quickly as they can. A patient with a cerebellar problem will demonstrate an intention tremor and past pointing (missing the target) (Fig. 11.9).

Meniere’s syndrome

Patients with Meniere’s syndrome occasionally present with an isolated episode of severe vertigo that lasts for hours and is followed by a sensation of unsteadiness and dizziness for days. Typically, however, the vertigo is preceded or accompanied by reduced hearing, tinnitus that changes in pitch in association with the episode and a sense of fullness or blocking of the ear. Over time, the attacks of Meniere’s syndrome recur, and fluctuations in hearing and episodes of tinnitus may be followed by a residual, low-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss. Fluctuating hearing levels associated with recurrent episodes of vertigo are central to the diagnosis of Meniere’s syndrome. Examination of the ear may show deafness but ENT examination is otherwise normal and CNS examination is normal.

Facial pain

Facial pain can be associated with sinusitis, dental abscesses and many other less common conditions. Helpful questions in the history are:

Sinusitis

Sinusitis can be viral or bacterial. Sinusitis presents with facial pain, blocked nose, mucopurulent nasal discharge and anosmia (loss of sense of smell). Referred pain may be present in teeth and ears. Evidence-based treatment consists of simple analgesia/NSAID, reduction of congestion and antibiotic treatment – usually amoxicillin as first line.10

Non-ENT causes of facial pain

Shingles may present with unilateral facial pain before the onset of blisters. Blisters associated with shingles are always unilateral. Patients should be advised to take simple analgesia and contact their own GP within 72 hours of the onset of any blisters (see Chapter 12). Trigeminal neuralgia can present with paroxysms of severe unilateral pain in the trigeminal nerve distribution lasting only seconds, separated by pain-free periods. The pain is often described as severe electric shocks. Contraction of the facial and masticatory muscles during an episode may occur. It should be treated with simple analgesia in the first instance and advice to see their GP.

Facial weakness (Bell’s palsy)

Facial weakness affects both sexes equally but is commonest between the ages of 10 and 40 years. It presents as a weakness of the seventh cranial (facial) nerve, the nerve that controls movement of the muscles of the face, the stapedius muscle, taste sensation of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and lacrimal gland secretory function. The cause is often not clear, although herpes infections may be involved. Pain behind or in front of the ear may precede weakness of facial muscles by 1–2 days. Loss of taste (anterior two-thirds of the tongue) and sensitivity to sound (hyperacusis) on the affected side may be present in greater than 50% of cases. Patients often complain of headache and that their face feels stiff or pulled to one side. Objectively they have difficulty with eating and drinking and a change in facial appearance with facial droop, difficulty with facial expressions, difficulty closing one eye, difficulty with fine facial movements, drooling due to inability to control facial muscles and dry eye secondary to being unable to close eye properly because of facial weakness.

Trauma (facial fractures)

Maxillofacial injury is rarely life-threatening unless it results in airway obstruction or severe blood loss. In both situations it is often associated with severe head and cervical spine injury. Many patients with more minor injuries will present the day following injury with swelling, bruising, closed eye and painful jaw. These patients will require a full assessment and usually referral to an A&E department, with imaging facilities. The exception is a suspected fractured nose. If this is the only injury the patient should be assessed for epistaxis, septal haematoma, and nasal obstruction. If none of these are present advice should be given regarding analgesia, not blowing or picking the nose, and to see their own GP for discussion on further management once swelling has subsided (usually around 7–10 days). If these symptoms are present referral to hospital for further assessment is required.

1 Cates C. An evidence-based approach to reducing antibiotic use in children with acute otitis media: controlled before and after study. BMJ. 1999;318:715.

2 Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two prescribing strategies for childhood acute otitis media. BMJ. 2001;322:336-342.

3 SIGN. Diagnosis and management of childhood otitis media in primary care. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2004. Available online: http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/66/section3.html (5 Mar 2007)

4 Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB, Sanders SL, Hayem M. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library. Oxford: Update Software; 2003. (Issue 2)

5 Takata GS, Chan LS, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence assessment of management of acute otitis media: 1. The role of antibiotics in treatment of uncomplicated acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2001;108:239-247.

6 Damoiseaux RAMJ, van Balen FAM, Hoes AW, et al. Primary care based randomised, double blind trial of amoxicillin versus placebo for acute otitis media in children aged under 2 years. BMJ. 2000;320:350-354.

7 NZGG. Acute otitis media: meta-analysis, 1998. New Zealand Guidelines Group. Available online: http://www.nzgg.org.nz/index.cfm (5 Mar 2007)

8 American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1451-1465.

9 Hotson JR, Baloh RW. Acute vestibular syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:680-686.

10 Del Mar C, Glasziou P. Upper respiratory tract infection. Clin Evid. 2003;9:1701-1711.